Frontispiece 1. Stonehenge 100. In October 1918, Cecil and Mary Chubb gifted Stonehenge to the nation, starting a programme of care and conservation that continues to the present. To celebrate the centenary, English Heritage gathered hundreds of local people to create this special aerial photograph. Other events in English Heritage's year-long programme have included a major exhibition at the Stonehenge Visitor Centre, co-curated with the British Museum and featuring objects from the British Museum's British and European prehistoric collections and from the Wiltshire and Salisbury Museums: ‘Making Connections—Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World’ runs until 21 April 2019. The year's programme of events culminated with a day of celebrations curated by artist Jeremy Deller, featuring new music, art and a tea party complete with a giant Stonehenge cake (www.english-heritage.org.uk/stonehenge © English Heritage).

Frontispiece 2. Fournoi shipwrecks. A diver inspects wreck 4 during the 2018 season of the Fournoi Underwater Survey in Greece. The shipwreck was discovered in 2015 on the eastern side of the Fournoi archipelago alongside four other wrecks dating from the sixth century BC to the seventh century AD. The ship was transporting a cargo of Late Roman 13-type amphorae when it was wrecked on the cliffs of Asprokavos in the seventh century AD. The site is one of 58 identified during survey of the archipelago, a collaborative project between the Hellenic Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities and the RPM Nautical Foundation. The discoveries document a maritime route connecting the Aegean and Black Seas with the Levant and Egypt throughout antiquity. (Photograph: Javier Mendoza; © 2018 Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities/RPM Nautical Foundation.)

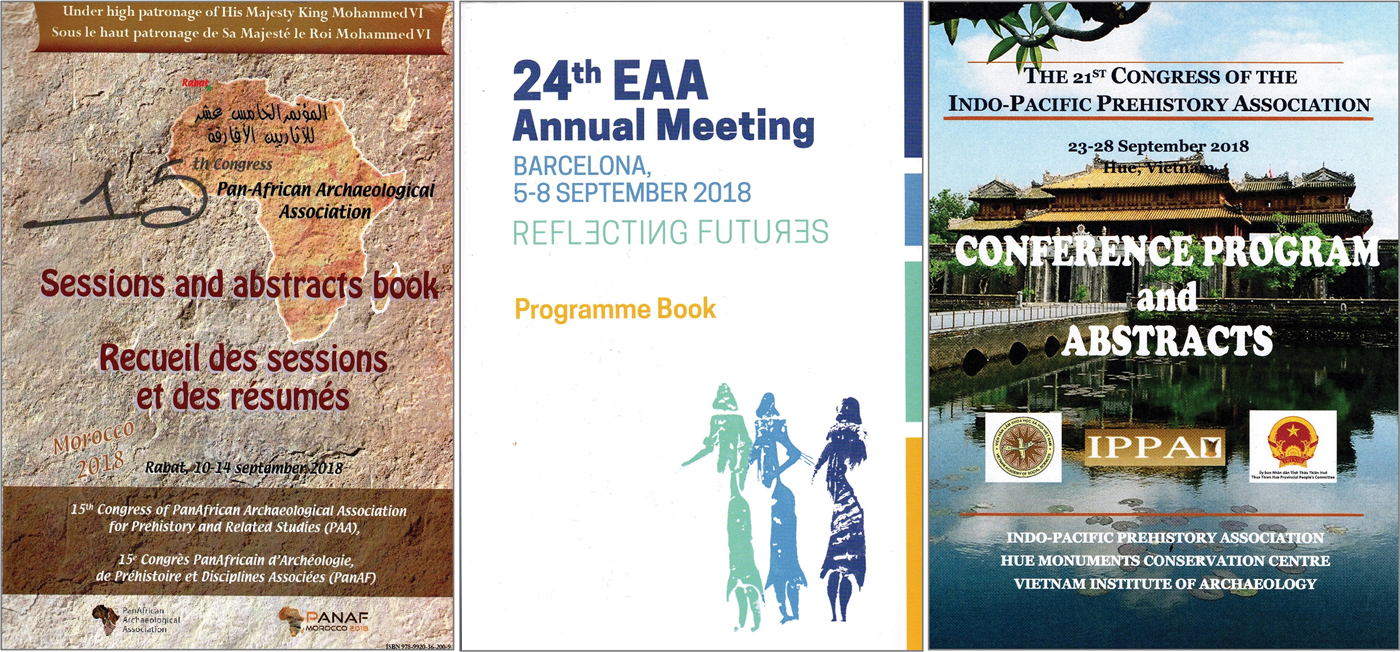

![]() During my first year as Editor, it has been a privilege to correspond with archaeologists from around the world. Every day brings a newly submitted manuscript, a peer-review report or an email communicating news of discoveries and developments. We have also taken our Antiquity conference stand to a number of international meetings—including EAA, PAA and IPPA (Figure 1; see below)—to catch up with the latest research and to meet with our contributors and readers. All of these interactions and experiences provide rich material for editorials. Earlier in the year, for example, conferences in the USA and China offered the opportunity to reflect on the archaeology of North AmericaFootnote 1 and East Asia.Footnote 2 In this final editorial of 2018, we set out to bring our readers news from other regions of the world by inviting colleagues representing South America, Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia and Australia to send updates on recent developments and events in their corner of the globe.

During my first year as Editor, it has been a privilege to correspond with archaeologists from around the world. Every day brings a newly submitted manuscript, a peer-review report or an email communicating news of discoveries and developments. We have also taken our Antiquity conference stand to a number of international meetings—including EAA, PAA and IPPA (Figure 1; see below)—to catch up with the latest research and to meet with our contributors and readers. All of these interactions and experiences provide rich material for editorials. Earlier in the year, for example, conferences in the USA and China offered the opportunity to reflect on the archaeology of North AmericaFootnote 1 and East Asia.Footnote 2 In this final editorial of 2018, we set out to bring our readers news from other regions of the world by inviting colleagues representing South America, Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia and Australia to send updates on recent developments and events in their corner of the globe.

Figure 1. Covers of the programmes from the September 2018 meetings of the PAA, EAA and IPPA.

The National Museum of Brazil

![]() Former President of the Brazilian Archaeological Society and current Antiquity Editorial Board member, Eduardo Goes Neves writes

Former President of the Brazilian Archaeological Society and current Antiquity Editorial Board member, Eduardo Goes Neves writes

In early June 2018, Brazil's National Museum in Rio de Janeiro celebrated the bicentenary of its foundation with a series of events for both the general public and the scientific community. Located in a historic building—the emperor's former winter palace—and set within a beautiful park, the Museum's exhibitions have long been popular with visitors; the institution is also the cradle of, and a major force in, Brazilian science. Less than two months after these celebrations, following another busy day on 2 September, fire broke out. The ensuing blaze destroyed the main museum building, which housed most of the displays, reducing to ash unique collections, libraries, rare manuscripts, scientific equipment and part of the archival history of the institution.

The National Museum is older than Brazil. It was founded by King John VI as the Royal Museum during the years when the Portuguese court had relocated to Rio de Janeiro to escape the advance of Napoleon. Established as a typical nineteenth-century natural history museum, it developed a local twist following Brazilian independence. Hence, there were donations from the royal family (Brazil was a monarchy from 1822–1889), including archaeological collections from Egypt and the West African Dahomey Kingdom, and a feather cloak presented to Emperor Peter I by the King of Hawai‘i. There were also recordings of now extinct Indigenous languages, and rare ethnographic and archaeological materials from the Amazon and the Andes, including osteological collections from shell mounds and an important series of skeletal remains of some of the oldest humans found in the Americas. In addition, there were palaeontological, zoological, mineralogical and botanical collections—the latter spared destruction because they were housed in a separate building.

The fire comes at a time of drastic reduction in public funding for Brazilian science and higher education. The Museum is a public institution associated with the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and the recent election of a far-right president in Brazil makes the outlook even bleaker, not only for the Museum but for Brazilian science in general. And yet the Museum will survive. Although many of the collections are lost forever, the institution still has 89 faculty members or curators, many of them leaders in their areas of expertise, and it hosts six PhD programmes (archaeology, social anthropology, botany, zoology, linguistics and quaternary geology) that currently count around 500 students. These staff and students are already mobilising to organise the generous offers of help from around the world.

The scale of the losses is difficult to grasp—as many as 20 million objects and specimens, some unique and irreplaceable. In the days and weeks after the fire, much attention focused on the fate of ‘Luzia’, whose skeletal remains were excavated from a cave in south-eastern Brazil and dated to around 11 500 years ago. Discovered in 1974, and key to ongoing debate about the colonisation of South America, Luzia was initially feared lost in the fire, but parts of her cranium and a femur have subsequently been recovered. Whether Luzia's bones retain scientific value remains to be seen, but her re-discovery is of great symbolic significance as the institution considers how to move forward. Offers of assistance have flooded in, including funds from Germany, offers of expertise from Egypt and, in order to start rebuilding the collections, samples from each of UNESCO's 140 global geoparks. Projects to collect photographs of the exhibits that can be used to recreate the collections virtually, and even to 3D print lost objects, are also underway. Such collaborative and creative responses will allow the work of the National Museum to continue into a new future. Meanwhile, more generally, the fire has underlined the importance of the digital recording of collections to insure against similar losses at other global cultural institutions, for sadly, such incidents are far from unprecedented. In January this year, for example, much of Jakarta's Maritime Museum, housed in a seventeenth-century warehouse complex built by the Dutch East India Company, was also badly damaged by fire. With so many threats to the in situ archaeological record—development, agriculture, trawling, erosion, climate change and warfare—it is sometimes easy to forget that objects relocated to museums and storehouses for conservation and preservation may still be vulnerable to loss.

European Association of Archaeologists

![]() News of the National Museum fire came through just as delegates were gathering in early September for the annual European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) meeting, held this year in Barcelona. Indeed, September featured a host of major conferences, some of them running concurrently. Hence, as EAA delegates descended on Barcelona, Roman frontier archaeologists headed to the Viminacium Archaeological Park in Serbia for the 24th Limes Congress and zooarchaeologists assembled in Ankara for the 13th International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ) conference. Margarita Diaz-Andreu of the EAA 2018 Local Organising Committee writes

News of the National Museum fire came through just as delegates were gathering in early September for the annual European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) meeting, held this year in Barcelona. Indeed, September featured a host of major conferences, some of them running concurrently. Hence, as EAA delegates descended on Barcelona, Roman frontier archaeologists headed to the Viminacium Archaeological Park in Serbia for the 24th Limes Congress and zooarchaeologists assembled in Ankara for the 13th International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ) conference. Margarita Diaz-Andreu of the EAA 2018 Local Organising Committee writes

The 24th EAA Annual Meeting in Barcelona attracted the largest number of participants in the history of the European Association of Archaeologists, with more than 3000 delegates and almost as many papers presented. The meeting's guiding motto was ‘Reflecting Futures’, chosen as a reference to the transmission of knowledge, from the past to the future, facilitated by the EAA conferences. As is the norm for these meetings, a series of themes—six on this occasion—were selected for this year's conference. The most popular, accounting for two-thirds of the sessions, were those related to ‘Theory and method’ and ‘Archaeological interpretation’. Notably, the communications grouped under the first of these themes demonstrated an imbalance between theory and method, weighted positively towards the latter and appearing to reflect an estrangement from the former, perhaps indicating some fatigue towards post-processual extremes, as well as the growing importance of data efficiency in a neo-liberal world. There were, of course, exceptions: sessions dealing with crises of ideas and models, agency, entanglement, post-humanism and other contemporary theoretical concepts; and, alongside well-established methods such as zooarchaeology and geomorphology, several sessions dealt with isotope analysis, big data and genetics. It was also remarkable to note—as the head of the scientific committee—the difficulty of allocating many of the proposed sessions to the conference themes; in some cases, only a single word might direct a session towards one theme rather than another.

The majority of the meeting's most popular sessions fell into the ‘Archaeological interpretation’ theme and dealt with identity, human-made environments, biographies of grave goods, monumentalism in Neolithic Europe, approaches to medieval buildings, textiles in ancient iconography, animal representations in the past, lithics as territorial markers, ecclesiastical landscapes, archaeoacoustics, art as material culture, beakers, and European hillforts. Themes 3–6 accounted for the last third of the meeting's sessions. Theme 4, on ‘Archaeology and the future of cities and urban landscapes’, featured another highly popular session, on archaeology and unsustainable urban growth. In comparison with previous years, the number of heritage sessions was low, a situation that can be explained by the unfortunate coincidence of dates with the Association of Critical Heritage Studies Group conference in Hangzhou, China. The other EAA 2018 conference sessions covered marine landscapes and museums, the latter being the first time that the meeting has included a theme on this topic, attracting a number of important sessions.

Next year, the EAA Annual Meeting convenes in Bern. The 25th conference, with the overarching theme of ‘Beyond Paradigms’ coincides with a time of considerable change and challenge to the European project. As EAA President Felipe Criado-Boado has noted, all that seemed solid back in 1994 has melted away, underlining the importance of organisations such as the EAA to build bridges (the theme of the 2017 meeting), to reflect futures and to look beyond paradigms. Specific themes for the Bern meeting include ‘Digital archaeology, science and multidisciplinarity’ and ‘Global change and archaeology’. The latter also serves as a reminder that the research communicated at EAA meetings extends far beyond Europe. In Barcelona, for example, the archaeology of Africa was well represented, with sessions including ‘African cosmopolitans: the Horn of Africa and the world’ and historical land use in Africa. One of a series of conference keynotes was a powerful presentation by George Abungu entitled ‘Doing archaeology and heritage in Africa: deconstructing and decolonising the narratives’, arguing in particular for the need for archaeologists to collaborate more fundamentally with local communities. Coincidentally or otherwise, this was also a topic of discussion at the next big conference of the season, starting just a day after the conclusion of EAA.

Pan-African Archaeological Association for Prehistory and Related Studies

![]() Held under the high patronage of King Mohammed VI and hosted by the Sciences Faculty of the Mohammed V University in Rabat, the overarching conference theme of the 15th Congress of the Pan-African Archaeological Association for Prehistory and Related Studies (PAA) was ‘Valorisation of African cultural heritage and sustainable development’. Freda Nkirote and Ibrahima Thiaw, the incoming and outgoing PAA Presidents respectively, write

Held under the high patronage of King Mohammed VI and hosted by the Sciences Faculty of the Mohammed V University in Rabat, the overarching conference theme of the 15th Congress of the Pan-African Archaeological Association for Prehistory and Related Studies (PAA) was ‘Valorisation of African cultural heritage and sustainable development’. Freda Nkirote and Ibrahima Thiaw, the incoming and outgoing PAA Presidents respectively, write

Since 1947, the Pan-African Archaeological Association for Prehistory and Related Studies has promoted various research interests across the disciplines that it represents through regular conferences and disputes resolution. The aim of the association is to bring together students and researchers from these disciplines, working across the continent, in order to provide a platform for the creation of discussion forums, networks and collaborations. In recent years, the Association has delved deeper into thematic areas of cultural heritage, food production, historical archaeology, environmental archaeology, rock art and climate change, in addition to topics such as lithic technology and metallurgy that have featured from the outset. While this has been a welcome step in furthering our understanding of African archaeology, the visibility within the Association of other related studies (palaeontology, geology and climatology) has been less vibrant. Going forward, PAA plans to renew the commitment to all its original aims and to try to ensure that, in the words of one of our members back in 1977, ‘African citizens become major players in their own drama’. This will not only be reflected in the leadership of the PAA, but also in the composition of its membership. To help achieve this, the permanent council has plans in place to appoint ethics and heritage committees, and to put into operation the new constitution, recently passed at the Rabat meeting, which will allow for membership registration. The constitution now ensures that the purpose of the Association is better defined, allowing for clear guidelines and improved operations. Congresses are held every four years, but the desire for the PAA to continue holding inter-congresses has grown, reflecting the need for greater visibility of the organisation and its work, more inclusivity, of both membership and subject matter, and rejuvenation of the PAA's core vision.

The sessions at the Rabat meeting ranged widely, from the earliest hominins through to trans-Saharan connections in the medieval and modern periods, and cultural heritage and community archaeology. Papers addressed rock art, lithic and metal technologies, Homo naledi and—reciprocating EAA 2018's Africa sessions—a series of papers on ‘Contacts entre Afrique et Europe durant la préhistoire’. A particular theme that emerged was the challenge of breaking down continent-wide generalisations while ensuring that local and regional differences remain linked within a wider pan-African narrative. Newly discovered human fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, for example, now document the presence of early Homo sapiens at 315±34 thousand years, some 100 000 years earlier than previously thought in this part of Africa.Footnote 3 This discovery opens the door to radically new ways of thinking about the origins of our species and the potential for genetic contributions from multiple regions of the continent. Following the meeting, delegates took excursions to visit some of Morocco's archaeological sites including, appropriately, Jebel Irhoud. The next PAA meeting convenes in 2022 in Zanzibar.

Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association

![]() Hot on the heels of the PAA meeting in Rabat was the 5th Landscape Archaeology Conference held jointly in Newcastle and—Antiquity’s own backyard—Durham, with 35 international academic sessions, plus regional excursions, spread across four days. Finally, to round off the September conference season, there was the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association conference. Philip Piper and Ian Lilley, the incoming and outgoing IPPA Secretaries-General respectively, write

Hot on the heels of the PAA meeting in Rabat was the 5th Landscape Archaeology Conference held jointly in Newcastle and—Antiquity’s own backyard—Durham, with 35 international academic sessions, plus regional excursions, spread across four days. Finally, to round off the September conference season, there was the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association conference. Philip Piper and Ian Lilley, the incoming and outgoing IPPA Secretaries-General respectively, write

The Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association recently met in Huế, Vietnam, for its 21st Congress. IPPA has its origins in the 4th Pacific Science Congress in Java in 1929, with the organisation's current name agreed at a meeting in Nice in 1976. Staged every four years, the IPPA conference is unique in that it attracts more than half its attendees from the Indo-Pacific region, with the remainder hailing from institutions across Europe and the Americas. This year some 600 delegates participated. The Congress provides an unparalleled opportunity for colleagues and families to come together to exchange ideas and listen to presentations covering the diverse range of research being undertaken across IPPA's vast region of interest. Participation of delegates from within the region, especially student-presenters, is supported by the Wenner Gren Foundation and the Granucci Fund.

The 2018 Congress underlined the breadth and depth of research undertaken by members of the IPPA community. The main themes focused on human origins and hominin diversity, early modern human behaviour and mobility, Late Pleistocene–Holocene social development and interaction, the emergence and spread of agriculture and the rise of states and complex societies. Topics such as heritage management, the role of Indigenous perspectives in archaeological research, and the mismanagement and theft of cultural heritage were also well represented. Developing closer collaboration in research and education among institutions across the Indo-Pacific region remains a major challenge, but one that IPPA is committed to supporting through the facilitation of workshops and a new website containing a directory of regional research centres, facilities and institutions. It is hoped that a new initiative and funding for human origins research across Southeast Asia, announced at the Congress by the National Geographic Society, will contribute to this effort. The grants are designed to support local early career researchers and to facilitate regional capacity building. The next IPPA Congress will be held in 2022. The venue will be chosen from bids assessed by the Executive Committee over the coming months. No doubt IPPA 2022 will be as successful as that of 2018 and all those that have come before.

Papers delivered at IPPA 2018 encompassed enormous geographic scope, from Madagascar to Fiji and from Japan to New Zealand, taking in research on China, India, Mongolia and all of Mainland and Maritime Southeast Asia. One of the key themes running through the conference programme, as with those before it, was the human colonisation of new lands. Many papers addressed the progress of anatomically modern humans into Island Southeast Asia, and the challenges and opportunities of fluctuating Pleistocene sea levels for the settlement of island chains and remote archipelagos. A perennial question concerns the date of the arrival of humans in Sahul—New Guinea and Australia—a theme picked up in our final report.

Australia

![]() Former President of the World Archaeology Congress and current Antiquity Editorial Board member, Claire Smith writes

Former President of the World Archaeology Congress and current Antiquity Editorial Board member, Claire Smith writes

Recent research has led to a reconceptualisation of the role of Australia and Southeast Asia in human evolution. Over the past few years, a number of sites have been dated to c. 50 000 BP, including Barrow Island, Carpenters Gap, Riwi, Serpents Glen and Warratyi. Then, in 2017, new findings from the Madjedbebe (formerly Malakununja II) site in northern Australia were used to push back the date for the Indigenous colonisation of the continent to 65 000 years.Footnote 4 New finds such as these highlight the role of art in documenting the colonisation of new lands, as does recent fieldwork in Borneo, Sulawesi and Timor-Leste.

Over the last decade or so, new research centres have focused on Australia's cultural and environmental heritage and its role in human evolution. These include the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution at Griffith University, the Centre of Archaeological Science at the University of Wollongong and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Biodiversity and Heritage. The role of rock art in human cultural evolution is a focus of research at the Centre for Rock Art Research + Management at the University of Western Australia, the Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit at Griffith University and the Indigenous Studies Centre at Monash University. This focusing of research is in part a response to the tri-annual Excellence in Research Australia assessments administered by the Australian Research Council (ARC).

Both social archaeology and community archaeology are strong in Australia. A research concentration on the colonial frontier has emerged from collaborative relationships and wider discussions between archaeologists and Indigenous Australians. Recent ARC-funded projects on colonialism include the archaeology of the Queensland Native Mounted Police, Indigenous foodways in the Cape York Peninsula, colonial museum collections, Aboriginal fringe campsites in the ‘long-grass’ (or urban periphery) of Darwin, colonial violence in South Australia's Riverland and contemporary social connections to place in the Dampier Archipelago. At the same time, new directions are being opened up by research in cognate disciplines. A recent study by Patrick Nunn, a geographer, and Nicholas Reid, a linguist, for example, have correlated Aboriginal oral traditions with scientific data on sea-level rise at 21 coastal sites, and found that changes from 7250–13 070 years ago are preserved in Aboriginal memories. Such work is likely to inspire archaeologists to develop future research into the relationship between climate change and oral traditions in Australia.Footnote 5

As this December issue goes to press, archaeologists are gathering in Auckland for a joint conference of the Australian Archaeological Association (AAA) and the New Zealand Archaeological Association (NZAA). The theme of the meeting is ‘Trans-Tasman Dialogues’, chosen to examine the past, present and future links across the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand. Themes include explorations of some of the two nations’ shared historical roots and the common goals of the two organisations towards fostering collaboration between archaeologists and Indigenous communities.

From Rio de Janeiro, via Barcelona, Rabat and Huế, to Auckland, my thanks to all the contributors for their updates on recent developments in their parts of the world.

In this issue

![]() In this final issue of 2018, we continue the theme of world archaeology, with papers reporting on research in places as diverse as the Alps (Loveluck et al.) and Amazonia (Navarro). We are particularly pleased to include an article on the excavation of a shell-mound in Nicaragua (Roksandic et al.)—a country not previously featured in the pages of Antiquity. In addition, we have several articles dealing with different types of dating and their chronological and cultural implications including radiocarbon (Manning et al.) and dendrochronology (Meadows et al.). We also feature articles on aspects of the Neolithic and domestication: Ricci et al. look at early agricultural colonisation in the Caucasus, and Gaastra et al. present evidence for early animal traction in the Balkans. Meanwhile, Fausto and Neves continue the debate raised by Denham et al.Footnote 6 in the October issue concerning the challenges of identifying ‘the Neolithic’ in tropical environments, here using ethnographic parallels to present a different approach to plant food production.

In this final issue of 2018, we continue the theme of world archaeology, with papers reporting on research in places as diverse as the Alps (Loveluck et al.) and Amazonia (Navarro). We are particularly pleased to include an article on the excavation of a shell-mound in Nicaragua (Roksandic et al.)—a country not previously featured in the pages of Antiquity. In addition, we have several articles dealing with different types of dating and their chronological and cultural implications including radiocarbon (Manning et al.) and dendrochronology (Meadows et al.). We also feature articles on aspects of the Neolithic and domestication: Ricci et al. look at early agricultural colonisation in the Caucasus, and Gaastra et al. present evidence for early animal traction in the Balkans. Meanwhile, Fausto and Neves continue the debate raised by Denham et al.Footnote 6 in the October issue concerning the challenges of identifying ‘the Neolithic’ in tropical environments, here using ethnographic parallels to present a different approach to plant food production.

In addition, readers will also find articles on a Shang-period village in China (Li et al.), foodstuffs in medieval Sri Lanka (Kingwell-Banham et al.), Paracas ceramic technology in Peru (Kriss et al.) and an experimental evaluation of pseudo-knapped artefacts in South Africa (van der Walt & Bradfield). We also have a Debate piece by Kenneth Brophy, plus three responses, highlighting how the politics of Brexit are influencing public reactions to the representation of prehistory and archaeological research on television, in newspapers and online. Reflecting the deep divisions that have emerged in the UK—and more widely across Europe and the West—Brophy draws attention to the challenges of communicating archaeological research in a time of social and political polarisation.

Finally, and as a counterpoint to the contemporary political climate, we remember that 100 years ago, on 11 November 1918, the guns fell silent across the battlefields of Europe. Over the past decade or so, the material legacy of that terrible conflict has been the subject of increased archaeological interest. Indeed, the most recent winner of the Antiquity Ben Cullen Prize employs historical aerial photography to map the landscape of war around the Ypres Salient.Footnote 7 Coinciding with the last of the centenary reflections on the culmination of the ‘war to end all wars’, we feature another article on the archaeology of that conflict. Excavations across the region of the former frontlines regularly bring up new evidence. In their article, Haneca et al. focus on wooden objects, which are often well preserved, including duckboards, shuttering, coffins and parts of tools and weapons. By combining wood-species identification and dendrochronology with detailed archival work, the authors are able to demonstrate the logistics involved in supplying the Western Front with timber. In a pre-plastic age, the combatants needed rapidly to expand the capacity of forests, and foresters, to harvest, process and transport the wood required to prosecute the war, drawing in—as our cover image depicts—landscapes as far from the front line as North America.

We wish all our readers and contributors around the world a peaceful and prosperous 2019.

1 December 2018