Introduction

Over 80 years between 1788 and 1868, Britain transported approximately 165000 people convicted of crimes to the Australian colonies (Maxwell-Stewart Reference Maxwell-Stewart2011: 17). These 139000 men and 26000 women were drawn from all parts of the Empire, with the course of their time as convicts and post-sentence lives shaping the early development of Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), New South Wales and Western Australia (Figure 1). During this period, an array of different and evolving convict management methodologies were applied, with those employed at penal stations representing the most punitive sphere of convict life and labour (Evans & Thorpe Reference Evans and Thorpe1992; Roberts & Garland Reference Roberts and Garland2010). In Van Diemen's Land, the penal settlement of Port Arthur was—and still remains—synonymous with this aspect of the past. It operated from 1830–1877 as a heavily guarded, closed penal hub situated on the Tasman Peninsula, and was predominantly devoted to the incarceration and labour of reconvicted male convicts (Brand Reference Brand1980). The punishment history of these men and the record and products of their labour have been captured in a documentary archive and a complex archaeological landscape. Together, these resources offer a remarkable opportunity to enhance understanding of the labour and punishment regimes implemented by the British and colonial governments.

Figure 1. Map showing locations mentioned in the text.

Project description

The ‘Landscapes of Production and Punishment’ project aims to draw upon a range of digital humanities and archaeological techniques to explore the physical impact of convict labour, with a focus on the industrial nature of the convict experience. It brings together archaeologists, historians and site interpreters to examine how such labour affected the built and natural landscapes, as well as the convict. Using the historical records and archaeological remains of the Tasman Peninsula's convict past, it will chart how evolving convict labour management practices: are reflected through changes in the ideologies of convict management, reform and punishment regimes; are manifested through the technologies, processes and physical organisation of craft, industry and labour; affected and shaped an iconic Australian convict landscape; influenced those convicts’ life and work experiences, including their post-incarceration careers; and can be contextualised in relation to other Australian and international landscapes of labour extraction (Tuffin et al. Reference Tuffin, Gibbs, Roberts, Maxwell-Stewart, Roe, Steele, Hood and Godfrey2018).

Port Arthur is key to understanding how convict labour was deployed and managed on the Tasman Peninsula, as it enjoys a remarkably intact built and archaeological resource that is matched by a rich documentary archive (Figure 2). Conventionally, penological zones have been represented as places of low-skilled, punishment-oriented labour: exclusionary, exploitative and inefficient. The weight of evidence, however, argues that Port Arthur was, in fact, a vast and vital proto-industrial centre, where work ranged from highly skilled artisan crafts to industrial workshop production and intensive gang labour (Figure 3) (Maxwell-Stewart Reference Maxwell-Stewart and Duffield1997). The archaeology and history of Port Arthur and the wider Tasman Peninsula provides a chance to explore how authorities and convicts negotiated and defined their workplace and its outcomes, in response to or regardless of the higher aims of colonial and metropolitan administrators. The project expands and integrates three datasets: the Peninsula's archaeological record, historical lifeways data for the convicts who served on the Peninsula and the administrative records generated by 47 years of convict labour management.

Figure 2. Aerial view of the main Port Arthur historic site today, facing north-east (photograph credit: PAHSMA).

Figure 3. Illustration showing Port Arthur in c. 1834. The settlement has been claimed from the bush, with evidence of clearance by the convict gangs in the foreground (John Russell, c. 1835, Port Arthur Van Diemen's Land, W.L. Crowther Library, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

The convict was a coerced participant in the formation and development of an industrialised punishment landscape. They worked in an array of situations and roles across a variety of spaces, where industrial and penological infrastructure requirements and labour management techniques comingled (Tuffin Reference Tuffin2007). The archaeological study therefore is multi-scalar, considering landscapes, site complexes, individual sites and structures, as well as the organisation of interior spaces associated with industrial production, but also convict accommodation and management. It also explores linkages between sites through associated transport systems, industrial processes and flows of material and people. In addition to re-analysis and synthesis of existing archaeological studies, new sites are being identified and recorded. To locate and analyse these features rapidly and cost-effectively, the project is using LiDAR remote sensing. Through this, the inter-relationship of these sites, as well as their constituent components, can be examined for evidence of how the administrators of the convict system reacted to the need to mix the requirements of labour and industry with those of incarceration (Figure 4). We are also examining these sites’ relationship to contemporaneous labour environments, with the type of labour, its processes and outputs helping us draw conclusions about the efficiency or otherwise of these places and processes (Tuffin Reference Tuffin2013). The latter will also be explored through materials analysis of the products of convict industry, available in existing archaeological and museum collections.

Figure 4. Elevation model of Port Arthur and its environs generated from LiDAR data. The major activities within the immediate catchment of the settlement are shown.

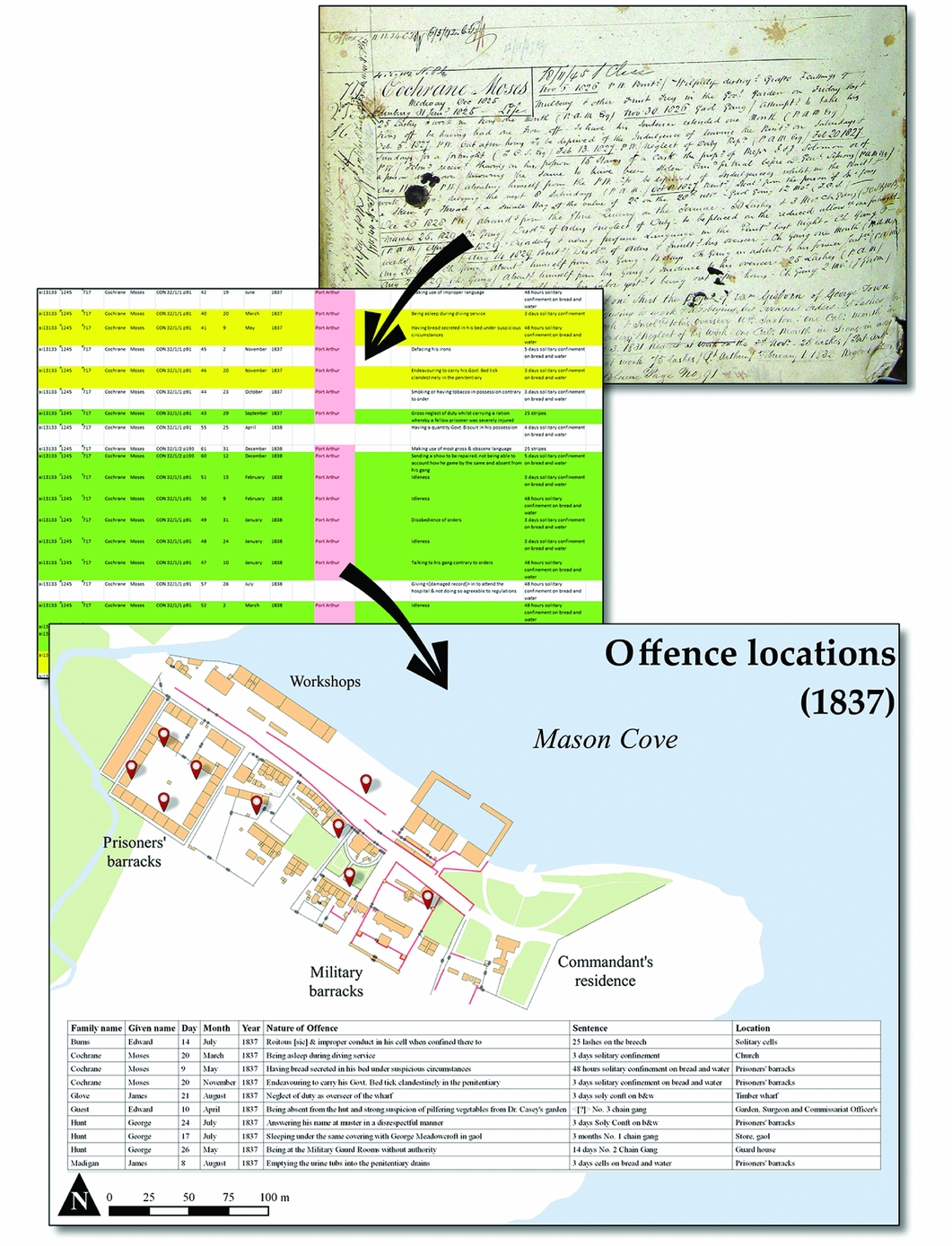

Using the documentary records, we are repopulating the historic landscape. Maps and plans, bolstered by the reports and correspondence recording day-to-day operations of a convict establishment, allow a reclamation of meaning for the remnants of the built landscape and can be measured against the archaeological record. A key component of this is an analysis of convict lifeways datasets, involving the synthesis of several unique and substantial historical convict biographical databases into a single unified dataset (Maxwell-Stewart Reference Maxwell-Stewart2016). This includes Port Arthur Historic Sites Management Authority's existing database of convicts sentenced to the station. From these data we are able to trace and quantify critical aspects of the ecology of convict labour, including absconding and industrial unrest, labour management practices, rates of accident, industrial-related pathologies and mortality associated with particular crafts, industries and roles at different locations (Figure 5). Many of these data fragments locate the convict within a known time and place; on the individual level, these data provide a coarse-grained view of the individual experience. Taken on a systematic level, however, the data illuminate the power dynamics active at these places.

Figure 5. Composite image showing the workflow of raw data from convict conduct records (top image) and transposing it to the mapped landscape (bottom image). Through this method we can geo-locate thousands of offences on the Tasman Peninsula (top image: conduct record of Moses Chochrane, #717, CON 32/1/1, Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office; bottom image: Landscapes of Production and Punishment; after Tuffin et al. Reference Tuffin, Gibbs, Roberts, Maxwell-Stewart, Roe, Steele, Hood and Godfrey2018).

This project presents an opportunity to confront what a landscape of convict labour looks like. It brings an archaeological appreciation of inter- and intra-site relationships, and of links between the built and modified environment, and melds it with the historian's skill in retrieving micro-narratives from the records to re-populate these extant landscapes. The matching of archaeological datasets with documentary research allows us to recreate the built and modified landscape of the nineteenth century, and to repopulate it with the convicts and supervisors who were responsible for its formation and development.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project (grant number DP170103642). Thanks are also due to Kelsey Priestman and our volunteer transcribers.