The burial of animals is attested in Egypt from the pre-Dynastic period through to Roman times. This phenomenon is observed across different animal species and involves varied funerary practices, although mummification is the most significant. Against this background, a series of burials of small animals, under excavation since 2011 at Berenike, suggests a unique example of pet-keeping rather than the religious or magical deposits found in the Nile Valley.

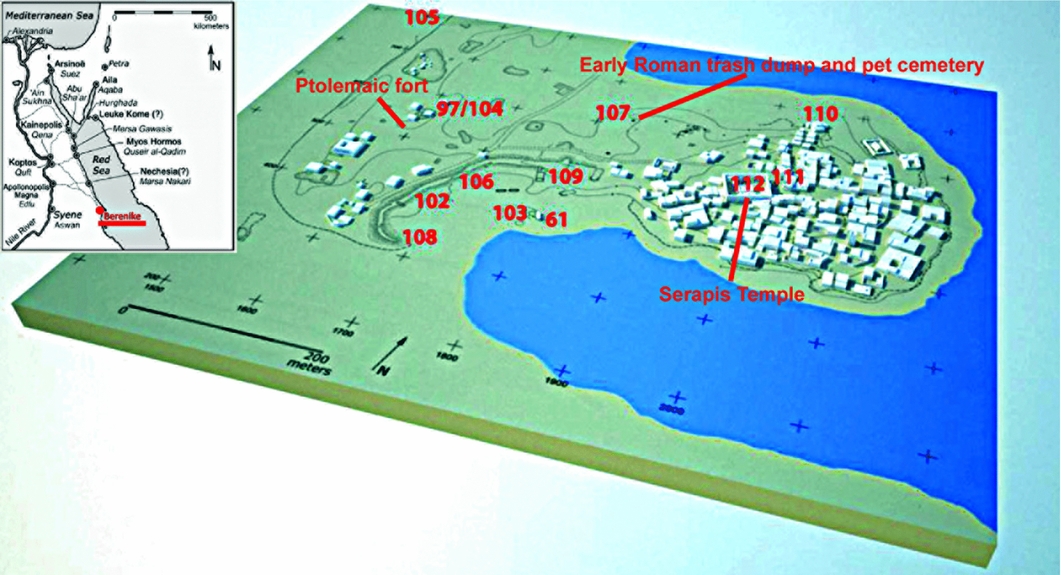

Berenike was a port-town on the Red Sea coast. It was established as a military post to protect the transhipment of African elephants being carried by sea for Ptolemy II (285 BC–246 BC). Following a period of decline, during the Early Roman period (first to third centuries AD), the Ptolemaic fort area revived to become one of the most important of the ports linking Upper Egypt, the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian Ocean (Sidebotham Reference Sidebotham2011). Systematic archaeological excavations were initiated in 1994 and have continued irregularly until the present day. Currently, research at the site is directed by Steven Sidebotham in cooperation with the Polish Centre for Mediterranean Archaeology, Warsaw University.

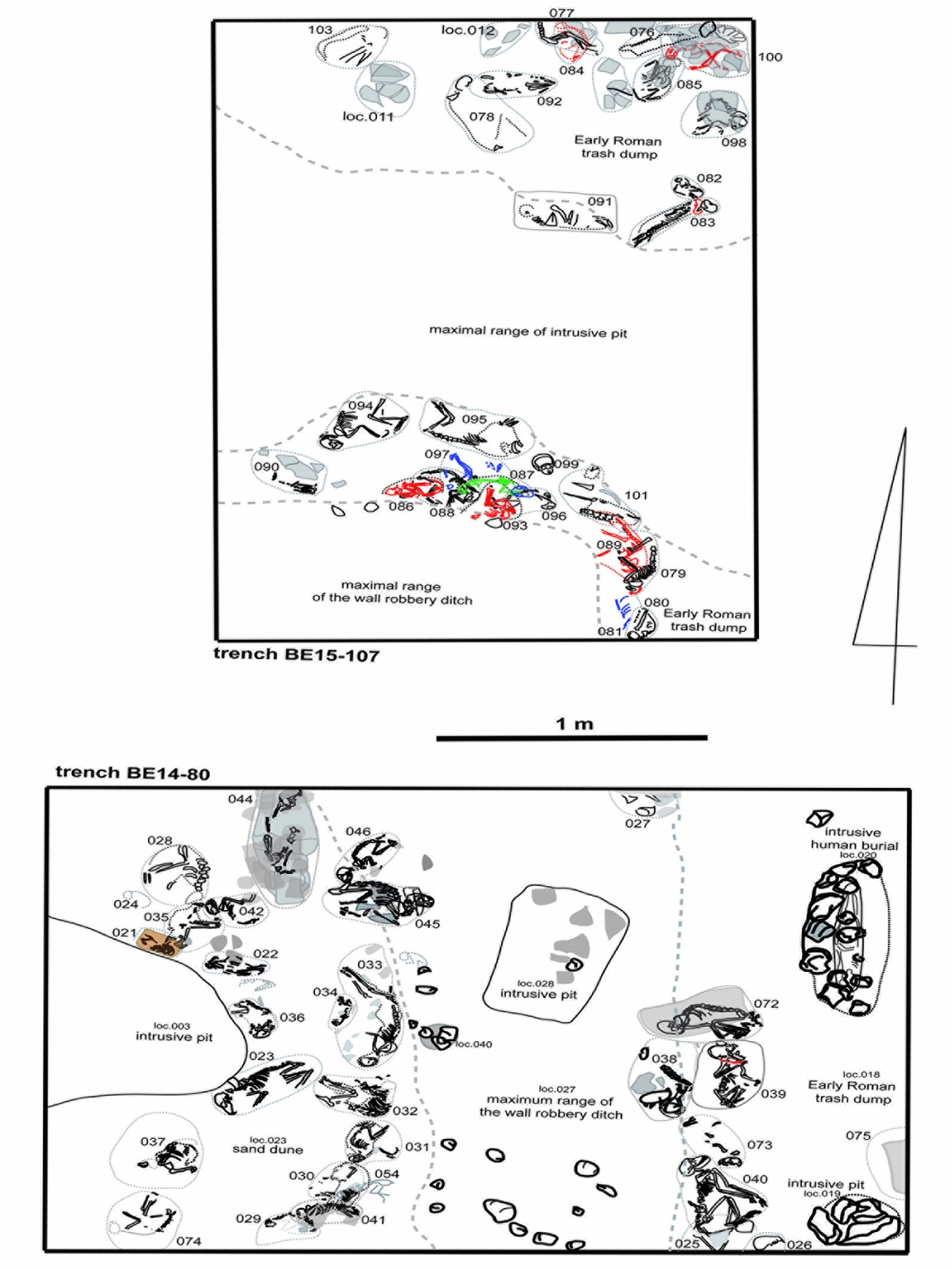

As part of these excavations, nearly 100 complete animal skeletons have been discovered in the area located to the west of so-called Serapis Temple on the outskirts of the Early Roman port (Figure 1). The stratigraphy and abundant material culture of this burial ground indicate that it was in use between the last quarter of the first century AD and the first half of the second century AD. The burial ground is located within a much wider zone, known as the “Early Roman trash dump” (Sidebotham Reference Sidebotham2011: 57) that has been under investigation since the start of archaeological work in Berenike, and which has produced a plethora of priceless finds. At the beginning of the first millennium AD, however, this place was an empty sector between the town and the much earlier Ptolemaic fort. Within this undulating area, the first burials of small animals were made during the last decades of the first century AD. The latest animal burials, dug into the rubbish dumped all across this area, can be dated to the second century AD (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Location of the Berenike and specific town zones (drawn by M. Hense).

Figure 2. Dispersion of small animal burials in excavated trenches—level of trash dump dated to second century AD (drawn by P. Osypiński).

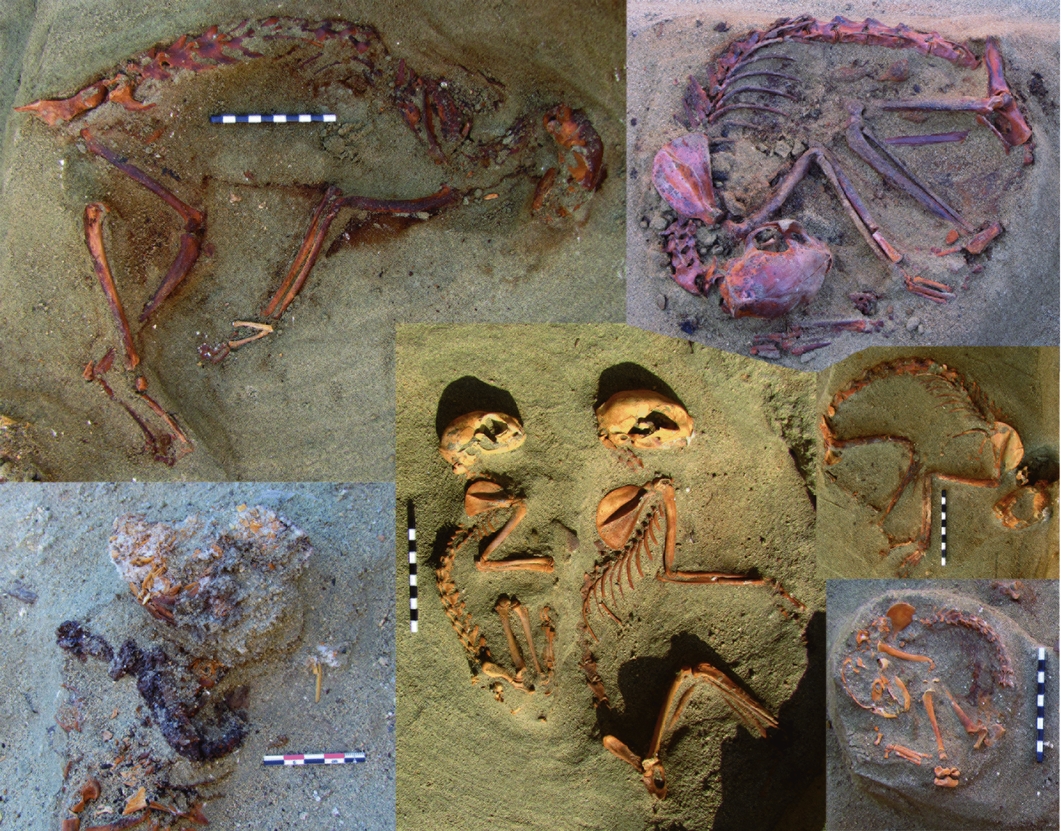

The animal burials from Berenike typically have no grave goods. A few examples of accessories, however, are preserved. Two young cats were found, each with a single ostrich egg-shell bead by their necks, and another three cats and a vervet monkey were buried with iron collars. In addition to individual animal inhumations, three burials contained two animals (Figure 3). So far, the only species found in such double burials are cats, and significantly, they always contain an adult and a juvenile.

Figure 3. Selection of cat burials from Berenike (photograph M. Osypińska).

The most frequently buried animal type in Berenike was the domestic cat. Egypt was undoubtedly one—and probably the most important—of the places where cats were first domesticated (Van Neer et al. Reference Van Neer, Linseele, Friedman and de Cupere2014). The Berenike cemetery has so far produced 86 complete cat skeletons and a number of other bones from disturbed burials. It should also be mentioned that single cat bones have been identified in other parts of the Early Roman port and its rubbish dumps. Currently, the assemblage of complete burials consists of 34.9 per cent adults, 27.9 per cent sub-adults and 37.2 per cent juveniles, infants and neonates.

Preliminary metrical analysis of the cat skeletal material suggests a homogeneous population. The data correspond well with the values from other north-east African domestic cats. So far, no evidence for other types of cats, such as the jungle cat (Felis chaus) known from the Nile Valley (Linseele et al. Reference Linseele, Van Neer and Hendrickx2007), has been identified at Berenike.

The next most common species recorded in the burial ground is that of dog (nine individuals), and at least two types of monkey: three grivets and one olive baboon.

Most of the well-preserved, complete animal skeletons are free of any pathologies. Particular attention has been paid to any evidence for the intentional killing of the animals—a practice known from the Nile Valley animal mummies—but there is no indication of this in the Berenike assemblage.

On the basis of the type of burial, the absence of mummification, the diverse species list and the absence of human inhumations, it is suggested that the Berenike cemetery reflects different intentions and cultural practices compared to the Nile Valley animal deposits. In my opinion, the described features suggest that the Berenike finds should be interpreted as a cemetery of house pets rather than deposits related to sacred or magical rites.

There is evidence confirming the ancient roots of the keeping of small pet animals, both in Egypt and Mediterranean Europe; the burials of favoured Roman dogs, for example, were commemorated with epitaphs. Dog burials in Egypt have also been interpreted as a reflection of humanity's emotional bond to “Man's best friend” (Ikram Reference Ikram2013: 299); typically, these dogs were buried with a human and so were presumably killed on the owner's death. In the case of cats, we have no evidence of this kind, either from Egypt or other regions. Instead, in Egypt, we find cat mummies produced on an almost industrial scale, especially in the first centuries AD.

Another specific feature of the Berenike cemetery is the very high percentage of cats. These animals were deeply respected throughout the pre-Roman periods, but such practices were never adopted by other societies. In Roman Europe, the cat initially became popular in the first century AD and its spread was aided by the Roman army (Toynbee Reference Toynbee1973). Thus, could we suspect that the eclectic evidence (both Egyptian and Roman) from Berenike reflects the adoption of the cat as a pet in this multicultural community? Naturally, there are plenty of reasons for keeping cats in a port-town, but the general segregation of the kitten and adult inhumations suggests a more complex relationship than pragmatic coexistence.

The animal cemetery in Berenike appears to be a unique site. Relations between people and animals in the past are usually approached through the prism of archaeozoology, but this too often neglects the possibility of pet-keeping, which is assumed to be a modern phenomenon. The finds from Berenike seem to question this assumption.