Introduction

Livestock production contributes an estimated 14.5% of human-induced global greenhouse-gas emissions (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Steinfeld, Henderson, Mottet, Opio, Dijkman, Falcucci and Tempio2013), contributing to global warming, as well as leading to degraded ecosystems, biodiversity and water resources (Godfray et al., Reference Godfray, Beddington, Crute, Haddad, Lawrence, Muir, Pretty, Robinson, Thomas and Toulmin2010; Foley et al., Reference Foley, Ramankutty, Brauman, Cassidy, Gerber, Johnston, Mueller, O’Connell, Ray, West, Balzer, Bennett, Carpenter, Hill, Monfreda, Polasky, Rockström, Sheehan, Siebert, Tilman and Zaks2011). As the human global population continues to increase, current agricultural practices will contribute to global mean temperature rises, which in turn will have severe and irreversible consequences (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Neff, Santo and Vigorito2015).

A 2006 report commissioned by the United Nations advised that immediate changes to the human diet, including substantial reductions in meat, particularly beef, are imperative to mitigating ‘catastrophic’ climate degradation (Steinfeld et al., Reference Steinfeld, Gerber, Wassenaar, Castel, Rosales and De haan2006). In 2019, 37 researchers from 16 countries collaboratively published the Eat-Lancet report (Willett et al., Reference Willett, Rockström, Loken, Springmann, Lang, Vermeulen, Garnett, Tilman, DeClerck, A., Jonell, Clark, Gordon, Fanzo, Hawkes, Zurayk, Rivera, De Vries, Majele Sibanda, Afshin, Chaudhary, Herrero, Agustina, Branca, Lartey, Fan, Crona, Fox, Bignet, Troell, Lindahl, Singh, Cornell, Srinath Reddy, Narain, Nishtar and Murray2019), which in line with previous research, advocates for the global adoption of a predominantly plant-based diet with significant reductions in consumption of animal products such as meat and dairy (Bajželj et al., Reference Bajželj, Richards, Allwood, Smith, Dennis, Curmi and Gilligan2014; Hedenus et al., Reference Hedenus, Wirsenius and Johansson2014; Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Reay and Higgins2018; Chai et al., Reference Chai, Van Der Voort, Grofelnik, Eliasdottir, Klöss and Perez-Cueto2019). The first advisory report from the UK’s Committee on Climate Change in 2020 also reflects these findings, advocating that beef and lamb consumption must be considerably reduced if the UK is to reach its net-zero greenhouse-gas emission target by 2050 (Committee on Climate Change, 2020). Recently, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) confirmed that the human race is not on the path to halt irreversible global mean temperature rises, and the biggest gap in investments has been in the agriculture and land sectors (Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022).

Despite this, evidence indicates that consumers are relatively unaware of how their diet could damage the environment (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Froggatt and Wellesley2014; Macdiarmid et al., Reference Macdiarmid, Douglas and Campbell2016). One way to promote sustainable diets is to label food products with information about sustainability (eco-labelling), for example, by providing details of water and land usage, as well as greenhouse-gas emissions, to allow comparisons across products. There has been substantial academic research examining the efficacy of eco-labelling over the last decade, and an ever-growing number of eco-labels exist (400 + according to ecolabelindex.com).

So far, studies have yielded mixed results; while some studies suggest eco-labelling has little influence on consumers’ food choices (Leire & Thidell, Reference Leire and Thidell2005; Padel & Foster, Reference Padel and Foster2005; Vermeir & Verbeke, Reference Vermeir and Verbeke2006), others have found that eco-labels increase sustainable food consumption (Vanclay et al., Reference Vanclay, Shortiss, Aulsebrook, Gillespie, Howell, Johanni, Maher, Mitchell, Stewart and Yates2011; Slapø & Karevold, Reference Slapø and Karevold2019). Labels such as the ‘Traffic Light Index’, which condenses information provided on the products’ environmental footprint, in the form of a traffic light with green (sustainable), yellow (moderate) and red (unsustainable) indicators, have been shown to be a viable and effective meta label that is easy to understand by consumers (Thøgersen & Nielsen, Reference Thøgersen and Nielsen2016).

Of course, it is conceivable that eco-labelling may only positively influence the behaviours of those consumers who are already motivated to act sustainably and who would welcome information that allows them to make goal-directed, time-efficient and effortless choices (Leire & Thidell, Reference Leire and Thidell2005; Thøgersen et al., Reference Thøgersen, Jøgersen and Sandager2012). However, in contrast, eco-labelling might have unintended consequences for people with lower motivation to act sustainably, who might reject the encouragement to behave in a certain way, possibly as a way to restore their perceived freedom in an act of defiance (Mühlberger & Jonas, Reference Mühlberger and Jonas2019). Given the possibility of these ‘boomerang’ effects for some consumers, it is important to consider other methods which may encourage sustainable dietary behaviours.

One method may be the use of social norms (i.e., social nudging) to promote more sustainable options. Social norms have been used to promote behaviours in other domains (Costa & Kahn, Reference Costa and Kahn2013; Ferraro & Miranda, Reference Ferraro and Miranda2013; Gromet et al., Reference Gromet, Kunreuther and Larrick2013), but to our knowledge have rarely been used to encourage more sustainable dietary options. One study, which considered grocery essentials (such as personal care items, drinks and dry grocery items) has highlighted the potential of social norms as incentivising tools to increase pro-environmental behaviour, noting that these social norms do not need much cognitive analysis by consumers (Demarque et al., Reference Demarque, Charalambides, Hilton and Waroquier2015).

As discussed, both eco-labels and social nudges have huge potential to influence food choice; however, they offer very different approaches. Social nudging, for example, is much easier to implement compared to eco-labelling, while the eco-label offers more in-depth information for consumers. Additionally, eco-labelling may provoke a stronger reactance by consumers, because of the environmental messaging (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Dixon and Hmielowski2019). As far as we are aware, research has not compared eco-labelling and social nudging directly. The information from this study could highlight a case for focusing on one label over the other. Furthermore, considering that motivation to act sustainably is increasing in the UK, particularly among generation Z (Deloitte, 2021), it is important to consider that consumers with a higher motivation to act sustainably might act differently or be differentially affected by such labels.

The primary aim of this study was to therefore investigate how an eco-label and a social nudge label influenced food choice compared to a control condition with no label. The secondary aim was to investigate whether an individual’s motivation to act sustainably influenced the efficacies of the eco-label and social nudge.

Materials and method

The study protocol and a detailed statistical analysis plan were pre-registered on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/muea3/. Ethical approval was gained from the Faculty of Science Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol, UK (approval code: 99962).

Design

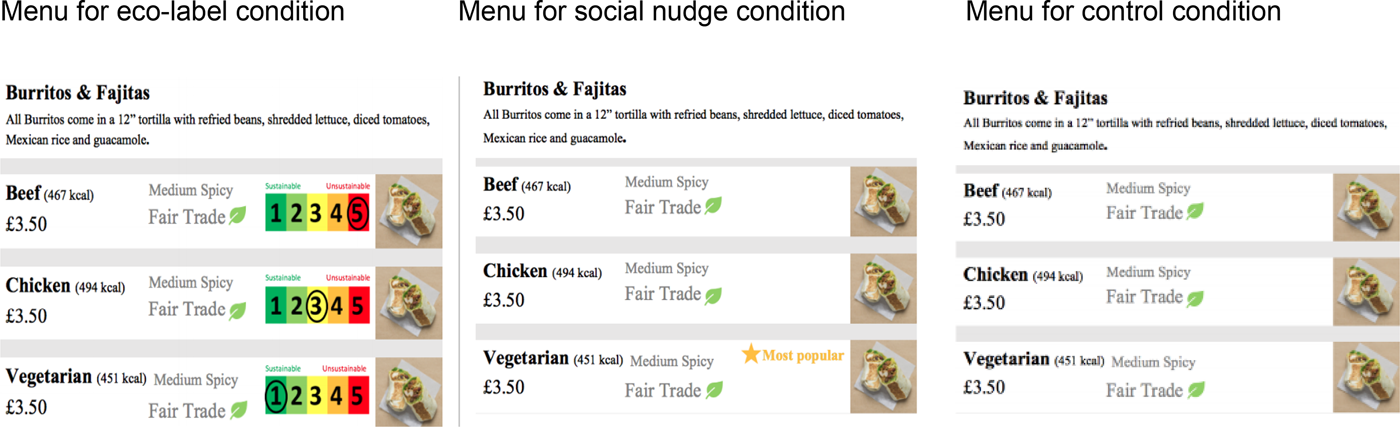

The study was a between-subjects, parallel-group, online experiment, conducted using the online survey software Qualtrics (Qualtrics, 2019). Participants were asked to choose a hypothetical food item from a menu containing three choices: a beef burrito, a chicken burrito or a vegetarian burrito. Participants were randomly allocated to one of three study conditions which varied in the labelling of the burrito: an eco-label, a social nudge label or no label control (Figure 1). There was an additional within-subjects component at the end of the study where reactance to both labels was measured. All participants were recruited through Prolific Academic (Prolific Academic, 2019) and data were collected in February 2020 over a 24-h period.

Figure 1. The menu shown for eco-label condition, social nudge condition and control condition.

Four hypotheses were tested:

Hypothesis 1: When given information about the sustainability and popularity of each meal, participants in both the eco-label condition and social nudge condition will make more sustainable food choices when compared to participants in the control condition.

-

1a. Participants in the eco-label condition will have a higher odds of choosing a chicken or vegetarian burrito over a beef burrito.

-

1b. Participants in the social nudge condition will have a higher odds of choosing a vegetarian burrito, over a chicken or beef burrito.

Hypothesis 2: Given differing information is provided on the eco-label and social nudge, participants in one of these experimental conditions will make more sustainable food choices (i.e., one condition will have a higher odds of choosing a vegetarian or chicken burrito over a beef burrito, and a higher odds of choosing a vegetarian burrito over a chicken burrito than participants in the other experimental condition).

Hypothesis 3: Given that only the eco-label provided information about the sustainability of the meal, the efficacy of the eco-label, but not the social nudge label, will be affected by participants’ motivation to act sustainably.

Hypothesis 4: Given the environmental information provided, participants will report stronger reactance to the eco-label compared to the social nudge label (a within-subjects analysis) when shown both labels.

Participants and recruitment

Using G*Power version 3, the sample size was calculated based on detecting a small overall effect size of 0.1 for a 3 × 3 χ 2 test with an α of 5% and power of 80%. For this, we would require at least 398 participants per study condition (1194 in total). To allow for possible attrition and given there was no a priori effect size estimate, we recruited 500 participants per study condition (1500 participants in total: 750 males and 750 females). This allowed for at least a 10% attrition rate via Prolific Academic. This was based on an analysis of a 3 × 3 table using a Chi-squared test or similar (e.g., multinomial logistic regression).

Participants were required to be aged 18 years or over, live in the UK, have eaten meat in the past week and not following any diet or have any dietary restrictions. Participants were reimbursed £0.60 on completion, in line with recommended reimbursement from Prolific Academic. Participants were unaware of the true study purpose, and therefore were blinded to their condition allocation.

Materials

Burrito menus

The menus were designed to resemble common food delivery app menus (see Figure 1). Menus included basic information which remained the same in all three study conditions, including a price (always £3.50 for each burrito), a Fairtrade logo, a spice indicator and a photo of the burrito. The calorific content of the burritos was also shown (either 451, 467 or 494 kcal). These calorific contents were chosen to be sufficiently but not meaningfully different and along with the other information described above, were included to prevent participants from guessing the true nature of the study. For each condition, six different calorie content menus were available, where each burrito was presented as the highest, medium and lowest calorie content, and participants were randomly assigned to view one of these calorie content menus.

Burrito labels

Participants in the control (no label) condition viewed the menus as described above. Those in the eco-label and social nudge conditions viewed menus with the following changes to the burrito labels.

Eco-label. The three burrito types were displayed alongside a traffic light system, with a scale of 1–5, which was circled at the appropriate sustainability level for that burrito: beef burrito – unsustainable, chicken burrito – neither sustainable nor unsustainable and vegetarian burrito – sustainable (Figure 1). This is consistent with research measuring the CO2 emissions (Espinoza-Orias & Azapagic, Reference Espinoza-Orias and Azapagic2012), water usage (Mekonnen & Hoekstra, Reference Mekonnen and Hoekstra2010) and impact on biodiversity from the different burrito ingredients (Crenna Sinkko & Sala, Reference Crenna, Sinkko and Sala2019).

Social nudge. The vegetarian burrito was presented alongside a popularity label consisting of a gold star next to the words ‘Most Popular’. The other two menu choices were presented with no label (Figure 1).

Measures

Burrito choice

The co-primary outcomes were the frequency that the vegetarian and chicken burritos were chosen over the beef burrito and the frequency that the vegetarian burrito was chosen over the chicken burrito.

Motivation to act sustainably

Self-reported motivation to act sustainably: the mean of six motivation to act sustainably questions, rated on a scale of 1 (not motivated to act sustainably) to 5 (very motivated to act sustainably). See Supplementary Material S1 for more information.

Label reactance

Reactance to each label (all participants were asked to rate the eco-label and the social nudge label at the end of the study): the mean of three reactance questions, rated on a scale of 1 (not reactive) to 5 (very reactive). See Supplementary Material S2 for more information.

Support for labels

Support for each label (all participants were asked if they supported the idea of an eco-label and social nudge label at the end of the study) was recorded as yes or no.

Procedure

The study was conducted using the online survey software Qualtrics and was advertised on Prolific Academic under the false purpose ‘Market research for food production’. On choosing to take part, participants were forwarded to a page which provided them with information about what the study would involve.

After consenting to take part, participants were informed about the upcoming food choice task and were instructed to ‘choose your food the same way you would if you were ordering your next meal to be delivered to you’. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three study conditions (control, eco-label, social nudge) and one of the six calorie content menus. Participants were then shown the burrito menu with the three options (beef, chicken or vegetarian burrito) and were asked ‘Which burrito would you like to order?’ (between-subjects design). To ensure participants read the menu, the participant could not move to the next question before the menu had been shown for at least 10s.

Once participants had chosen their burrito, they completed questions about their motivation to act sustainably, followed by questions relating to the awareness of the study aims and labels (Supplementary Material S3). All participants were then presented with the eco-label and the social nudge label (in a randomised order) and asked questions assessing reactance and support towards them (within-subjects design).

Participants then completed demographic information, within which they were presented with an attention check question, asking them to select ‘extremely unlikely’ from five listed responses. Finally, participants had the opportunity to comment on the use and support of the labels to promote sustainable food choice. On completion of the study, participants were taken to a final page which debriefed them on the purpose of the study, before redirecting them to Prolific Academic for reimbursement. The task took approximately 5 minutes to complete.

Statistical analysis

Participants who failed the attention check (n = 61) were excluded from the analysis.

To assess if there was any difference between all three study conditions, we conducted a Chi-squared test. To address hypotheses 1a and 1b, we conducted a multinominal logistic regression model to compare the primary outcome (frequency that each type of burrito is chosen) between the three study conditions. The model was fitted twice to change the reference category, firstly where the comparison condition was the beef burrito, and secondly where the comparison condition was the chicken burrito.

A similar approach was adopted to address hypothesis 2, where the reference category was the social nudge condition. For all models, all additional pairwise comparisons are also reported between study conditions. An odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), along with an associated p-value, are reported. Statistical significance was set to 5%; however, some study conditions were used more than once in comparisons, and therefore some p-values should be treated cautiously.

To address hypothesis 3, we added an interaction term between study condition and motivation to act sustainability (as a continuous variable) to the primary outcome model. We report each interaction term, alongside the OR and 95% CI.

To address hypothesis 4, we conducted a within-subjects repeated measures mixed model to compare the mean reactance scores for the eco-label and the social nudge, with adjustment for the study condition. In the pre-registered statistical analysis plan, we had planned to also adjust for the order in which the participant saw each label, but these data were not available on study completion. The mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for the mean difference are reported alongside the p-values.

We conducted two planned sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome model excluding (i) those participants who were in either the eco-label or social nudge condition, and who did not correctly identify the label from their condition at the end of the study (n = 146) and (ii) those participants who correctly identified the aim of the study (n = 720). We had also planned to conduct a third sensitivity analysis repeating the above models, but with the addition of an adjustment for randomised calorie content menu version; however, this information was unavailable upon completion of the study. Due to a disproportionate amount of exclusion in the eco-label and social nudge conditions (Supplementary Material S4), a fourth unplanned sensitivity analysis was conducted including those participants that failed the attention check (n = 61). Results for all sensitivity analysis remained similar to the main analysis and are presented in the Supplementary Material S5.

Results

Participant characteristics

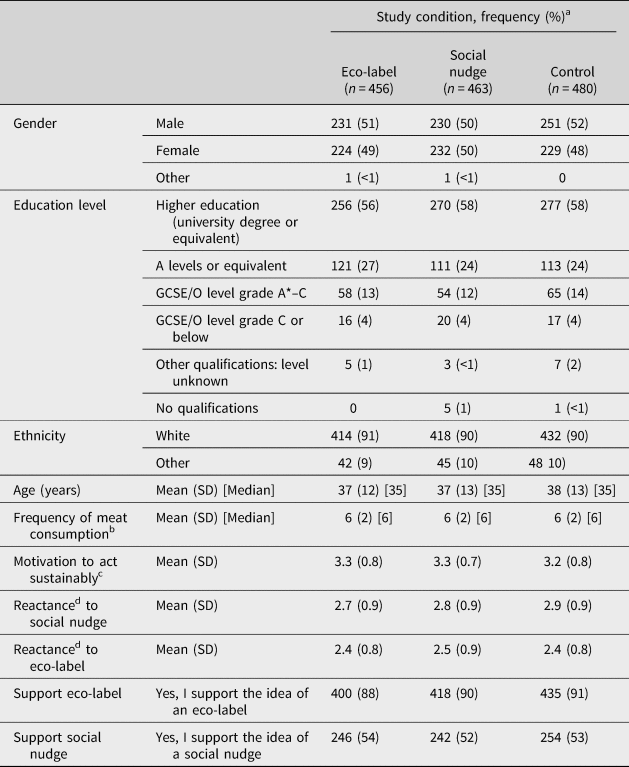

The Consort diagram in Supplementary Material S4 shows the flow of participants through the study, including exclusions and randomisation to conditions. This shows that from 1500 participants who self-selected to complete the study, data from 1399 participants were included for analysis (eco-label n = 456, social nudge n = 463, control n = 480). The mean age was 38 years (SD [standard deviation] = 12.8), 50% were female, 90% reported themselves as white ethnicity and 59% reported having a higher education level (university degree [or higher] or a vocational equivalent). Participants showed high levels of support (90%) for introducing eco-labels, with a reduced number supporting the social nudge (53%). Demographic characteristics between study conditions are reported in Table 1 and appear balanced between conditions.

Table 1. Demographic data between study conditions (n = 1399)

a Unless otherwise stated.

b per week.

c Rated on a scale of 1 (not motivated to live sustainably) to 5 (very motivated to live sustainably).

d Rated on a scale of 1 (not reactive) to 5 (very reactive). Standard deviation (SD).

Burrito choice

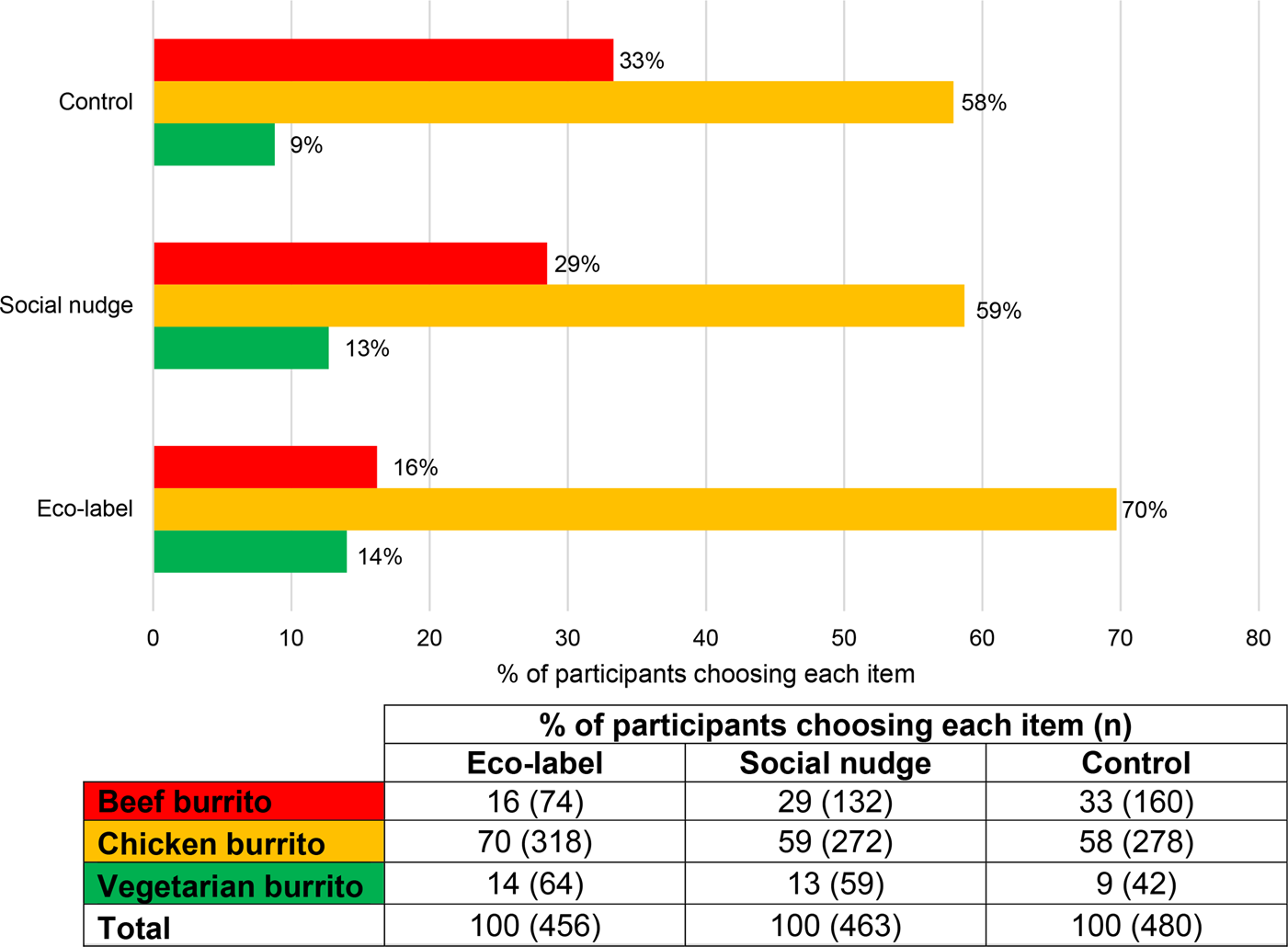

Results of a 3 × 3 Chi-squared test showed evidence of a significant difference between the three study conditions (χ 2 [4] = 40.157, p < 0.001). Figure 2 presents the percentage of participants choosing each type of burrito between study conditions. Choice of the beef burrito was highest in the control condition (33%) and lower in the social nudge (29%) and eco-label (16%) conditions. Choice of the vegetarian burrito was highest in the eco-label condition (14%), followed by the social nudge condition (13%) and lowest in the control condition (9%). The results of the multinomial linear regression on the frequency that each type of burrito is chosen are described below and presented in Table 2.

Figure 2. Percentage of participants choosing each type of burrito between study conditions (n = 1399).

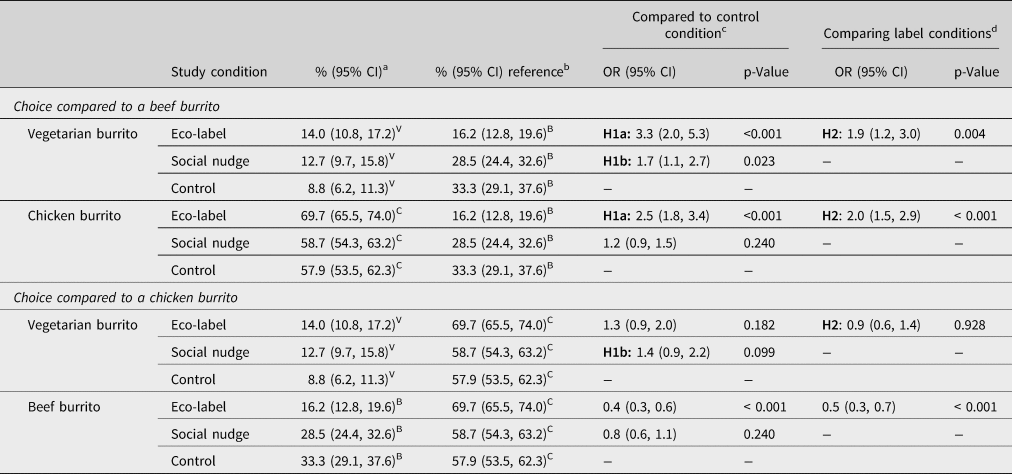

Table 2. Results of multinomial logistic regression for the primary outcome (frequency that each type of burrito was chosen) (n = 1399 [eco-label condition: 456, social nudge: 463, control: 480])

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. H1a (related to hypothesis 1a). H1b (related to hypothesis 1b). H2 (related to hypothesis 2).

− indicates the reference category.

a The % of participants who chose the burrito listed in the first column (V Vegetarian burrito, B Beef burrito, C Chicken burrito).

b The % of participants who chose the reference category (B Beef burrito or C Chicken burrito).

c Reference category = control (no label) condition.

d Reference category = social nudge condition.

Sustainable food choice (hypothesis one and two)

In line with hypothesis one, compared to the control condition, there was evidence that participants in the eco-label condition had a higher odds of choosing a vegetarian (OR = 3.3 [95% CI 2.0, 5.3], p < 0.001) or chicken burrito (OR = 2.5 [95% CI 1.8, 3.4], p < 0.001), over a beef burrito. There was also some evidence that compared to the control condition, participants in the social nudge condition had a higher odds of choosing a vegetarian burrito, over a beef burrito (OR = 1.7 [95% CI 1.1, 2.7], p = 0.023), but not, contrary to our hypothesis, over a chicken burrito (p = 0.099).

In line with hypothesis two, there was evidence that compared to those in the social nudge condition, participants in the eco-label condition had approximately twice the odds of choosing a vegetarian burrito (OR = 1.9 [95% CI 1.2, 3.0], p = 0.004), or chicken burrito (OR = 2.0 [95% CI 1.5, 2.9], p < 0.001), over a beef burrito. There was also evidence that these participants had decreased odds of choosing a beef burrito over a chicken burrito, compared to the social nudge condition (OR = 0.5 [95% CI 0.3, 0.7], p < 0.001), but contrary to our hypothesis, there was no evidence that they had greater odds of choosing a vegetarian burrito, over a chicken burrito (p = 0.928).

Motivation to act sustainably (hypothesis 3)

The mean motivation to act sustainably score was 3.3 (SD = 0.8), which was above the mid-point value of 2.5 on the 5-point scale (where 5 = very motivated to act sustainably), and was similar between study conditions (Table 1).

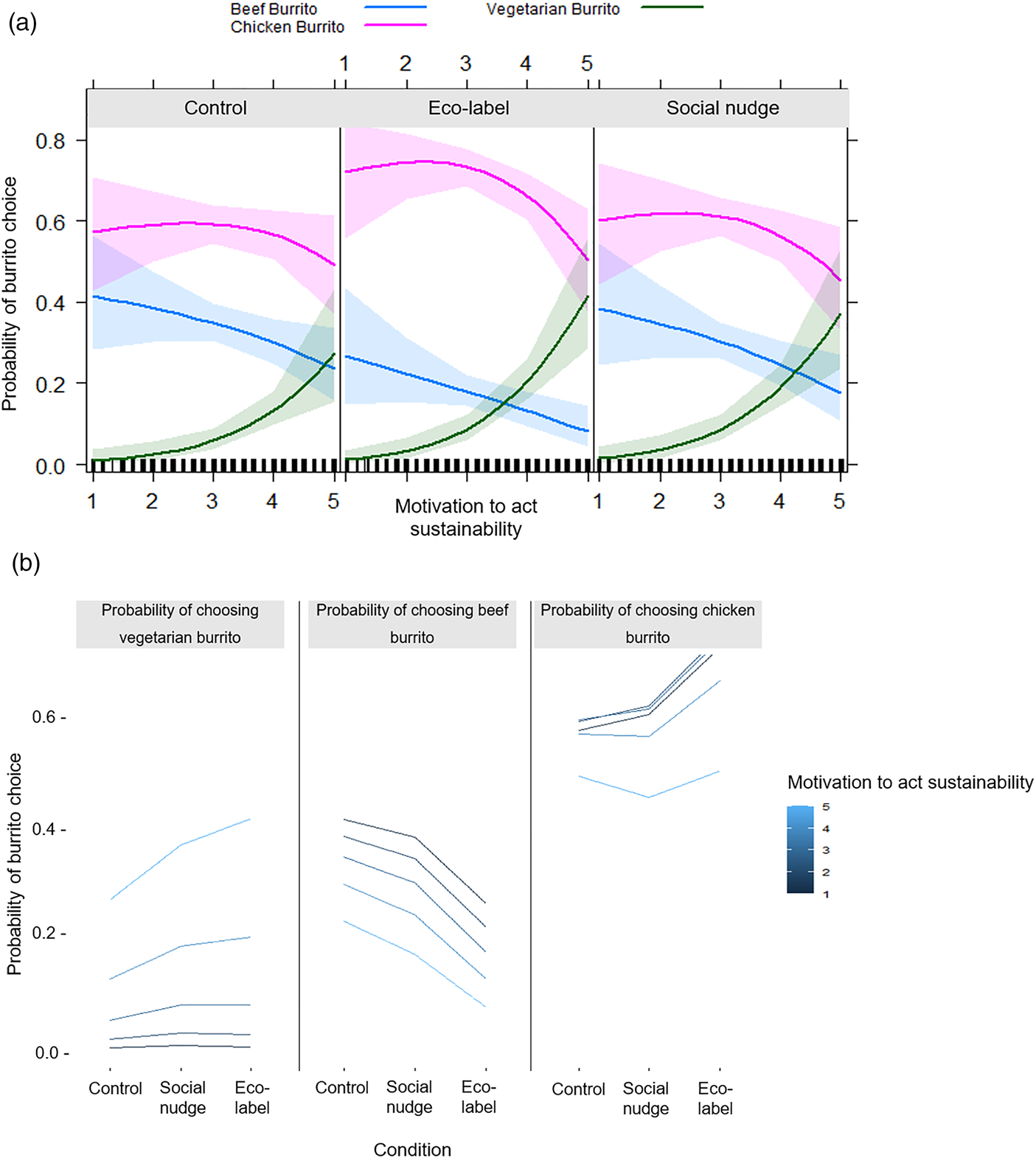

When the main effect of motivation to act sustainably was added to the model, we observed an interaction with the study condition, indicating that the choice of a vegetarian burrito over a chicken or beef burrito was modified by motivation to act sustainably across all study conditions. As shown in Figure 3(a), in line with our hypothesis, this interaction effect was most predominant in the eco-label condition with the odds of choosing a vegetarian burrito over a beef (OR = 3.3 [95% CI 2.0, 5.3], p < 0.001) or chicken (OR = 2.7 [95% CI 1.7, 4.0], p < 0.001) burrito increasing with motivation to act sustainably. To a lesser extent, and, contrary to our hypothesis, there was also evidence of similar interactions in the social nudge condition (choosing a vegetarian burrito over a beef burrito: OR = 2.7 [95% CI 1.7, 4.3], p < 0.001 and choosing a vegetarian burrito over a chicken burrito: OR = 2.4 [95% CI 1.6, 3.7], p < 0.001). Results of all interaction terms between study condition and motivation to act sustainably can be seen in Supplementary Material S6.

Figure 3. Marginal effects plot of the multinomial logistic regression model (two main effects of study condition and motivation to act sustainability and the interaction term) (n = 1399). Marginal effects plot reference: (Fox & Hong, Reference Fox and Hong2009). (a) Motivation score by predicted probability of burrito choice (shaded areas represent 95% CI of the probability); (b) For each burrito type, experimental condition by predicted probability of burrito choice (lines represent levels of motivation to act sustainably; 1 = not motivated, 5 = very motivated)

Figure 3(b) shows how the probability of choosing different burrito options changes according to motivation to act sustainably across all three conditions. In panel 1, we see that for participants with a low motivation to act sustainably (a score of 1–3 out of 5), the probability of choosing a vegetarian burrito remains similar, regardless of the study condition (i.e., the experimental manipulation does not seem to increase their choice of vegetarian burrito). However, for those participants with a higher motivation to act sustainably score (4–5 out of 5), being in the social nudge condition, but particularly the eco-label condition increased the probability of choosing a vegetarian burrito. Panel 2 of Figure 3(b) shows no evidence of an interaction effect between motivation to act sustainably and study condition when choosing a beef burrito choice. However, Panel 3 of Figure 3(b) suggests that being in the eco-label condition increased chicken burrito choice compared to being in the control condition or social nudge condition, but only for those with a motivation to act score of 1–4. For those with the highest score of 5, there appeared to be little effect of condition on chicken choice, and this effect seems to be largely driven by the increased vegetarian choice for those with the highest motivation to act sustainably score in the eco-label condition.

Reactance to label (hypothesis four)

Contrary to hypothesis four, there was evidence that participants had a stronger reaction to the social nudge label (mean reactance score of 2.81 [SD = 0.88]) compared to the eco-label (mean reactance score of 2.44 [SD = 0.85]) (t [1396] = 16.2, MD = 0.36 [85% CI 0.32, 0.40], p < 0.001). There was a significant interaction term between label and study condition (p = 0.003), with the difference in reactance between labels most predominant in the control group (Supplementary Material S7). However, this is expected as participants in the control condition had not seen either label previously, whereas participants in the eco-label condition and social nudge condition had previously seen the labels.

Discussion

In this online experimental study, we found evidence that both the eco-label and social nudge label were effective in influencing choices towards more sustainable foods (Mekonnen & Hoekstra, Reference Mekonnen and Hoekstra2010; Espinoza-Orias & Azapagic, Reference Espinoza-Orias and Azapagic2012; Crenna Sinkko & Sala, Reference Crenna, Sinkko and Sala2019). There was evidence that more vegetarian and chicken burrito choices were made in the eco-label condition, over the beef burrito, compared to the control condition. In the social nudge condition, there was also evidence that participants chose a vegetarian burrito over a beef burrito, but this label did not drive participants to choose a vegetarian burrito over a chicken burrito. Although both labels were effective at promoting more sustainable food choices, the eco-label was the most effective in this goal.

In all conditions, a higher motivation to act sustainably predicted choosing a vegetarian burrito over a beef or chicken burrito. Although the choice of burrito was modified considerably by motivation to act sustainably across all study conditions, as expected, the efficacy of this effect was most predominant in the eco-label condition. However, contrary to our hypothesis, we found evidence that the choice of burrito was also modified by the motivation to act sustainably in the social nudge condition. Again, contrary to our hypothesis, there was evidence that participants had a stronger negative reaction (i.e., reactance) to the social nudge label compared to the eco-label.

As far as we are aware, this is the first study to directly compare an eco-label with a social nudge, as well as consider any interaction between this labelling and motivation to act sustainability. The study had a large sample size, which was representative of the UK population in terms of gender, age and ethnicity (Office of National Statistics, 2011), therefore increasing external validity, and included a range of participants who regularly eat meat.

Nevertheless, the study has some limitations. Firstly, our sample had a slightly elevated representation of adults who had a university degree or higher, compared to the UK population (57% compared to 35%) (Office of National Statistics, 2011). Secondly, the social nudge label, although often used in real-life settings to indicate popularity, was not related to the actual popularity of the burritos (as it was a hypothetical scenario), and this could be why it invoked a stronger negative reaction than hypothesised. Whether this untruthful nudge would be acceptable in real-life settings is a possible issue with this study. Similar alternative nudges such as ‘Our customers love’, ‘We recommend’, or sustainability-themed nudges such as ‘Join a growing movement’, could be tested in future research. In fact, in 2022, the World Resources Institute conducted a multi-stage online experiment which tested sustainability-themed messaging on menus. These results suggested that displaying thoughtfully framed environmental messages on restaurant menus could help to nudge diners to order more vegetarian meals (Blondin et al., Reference Blondin, Attwood, Vennard and Mayneris2022).

In addition, our findings related to the extent to which motivation to act sustainably can predict meal choice should be treated with some caution as this question was asked after participants made their meal choice. This design decision was made as the alternative (i.e., asking the question prior to meal choice) would likely have primed participants to make more environmentally sustainable choices, influencing our primary outcome measure.

Finally, because this study took place in an online setting, the environment in which the participants took part could not be controlled and therefore external factors could have affected food choice (i.e., hypothetical food selection online may not translate into a real-world setting). Indeed, it is possible that social desirability bias may have impacted the results, with participants in either of the experimental conditions guessing the nature of the study and choosing an option that they felt reflected well on them (i.e., choosing the more environmentally friendly option in the eco-label condition) or that which they thought the experimenter wanted them to choose. Furthermore, no money was exchanged during this experiment which would again not reflect a real-world setting, although we note that food choices can often be made outside of monetary systems (e.g., at a buffet). Although the price of each burrito remained consistent during this experiment, therefore suggesting a greater experimental certainty that any differences would not be due to price, we recognise this as a limitation, since, for example, vegetarian food is typically cheaper than meat options in real-world settings.

Despite these limitations, our results are consistent with findings that eco-labelling and social nudging promote more sustainable food choices (Vanclay et al., Reference Vanclay, Shortiss, Aulsebrook, Gillespie, Howell, Johanni, Maher, Mitchell, Stewart and Yates2011; Filimonau et al., Reference Filimonau, Lemmer, Marshall and Bejjani2017; Slapø & Karevold, Reference Slapø and Karevold2019). In addition, our results indicated that the eco-label influenced food choice to a greater extent than the social nudge. This success of the eco-label may be reliant on the ability of the consumer to make comparisons between products. In fact, in the optional final comments in this study, some participants reported the eco-labels deterring beef choices after they were able to make comparisons (Supplementary Material S8).

As hypothesised, we had expected motivation to act sustainability to modify burrito choice but only among those participants in the eco-label condition. This was mainly because participants in this condition were the only participants given information about the sustainability of the burrito choices. However, the fact that we saw this modifying effect in all study conditions suggests that participants were possibly already aware of what the more sustainable food choices were and participants who were motivated to act sustainably made more sustainable choices regardless of the condition they were in.

Additionally, when participants with a higher motivation to act sustainably, who were more likely to choose the vegetarian burrito regardless of study condition, were presented with the eco-label, their odds of choosing the vegetarian burrito were increased even further than the other two conditions. As education on climate change increases, and consumers become more aware that their individual food choices can help to reduce environmental damage, causing more people to want to act sustainably, this additional consumer information could be fundamental to behaviour change. Future research may wish to consider a virtuous cycle, whereby it is possible that being exposed to information on an eco-label could increase motivation to act sustainably, which could in turn increase sustainable choices, and so on. Currently, sustainability information about our food is not made freely available in the UK, contributing to a lack of freedom to choose for those individuals who are motivated to do so.

Overall, the choice of a vegetarian burrito was relatively low (in total, 12% of participants choose a vegetarian burrito); however, this is in line with previous studies indicating vegetarian food choice in meat-eating individuals to be 13% (Bacon & Krpan, Reference Bacon and Krpan2018). Additionally, the choice of beef burrito was more likely to be reduced and replaced with a choice of chicken burrito, rather than choice of a vegetarian burrito increased. However, this is consistent with research showing that people are more averse to choosing red-labelled products than they are enticed by green-labelled products (Scarborough et al., Reference Scarborough, Matthews, Eyles, Kaur, Hodgkins, Raats and Rayner2015). Given that reducing beef intake is a specific component of British sustainability strategies, eco-labelling could provide an effective method to achieve this.

In addition to these findings, we found evidence, contrary to our hypothesis, that reactance was stronger to the social nudge than it was to the eco-label. Our study also showed a high level of support for the eco-label (90%). Both of these results suggest that introducing a mandatory eco-label that utilises a grading system would not only allow comparisons between products and increase more sustainable food choices but also seems to elicit lower negative reactance than a social nudge and is widely supported by the meat-eating public.

Policy implications

A mandatory label could help to address some of the information gaps consumers have concerning the sustainability of the products they are buying and enable people to choose sustainably if they wish. For example, considering the mean motivation to act sustainably score for participants in this study was 3.3 (over half of the 1–5 scale), but the mean consumption of meat was six times per week, this suggests that consumer choices could further benefit from more information about their meal, via a mandatory eco-label, being presented on packaging.

Currently, many companies are using non-regulated eco-labelling as an advertising technique which has further led to customer confusion on the sustainability of products (Staffin, Reference Staffin1996; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2008). A regulated traffic light eco-label, similar to standardised nutritional information on food packaging, would facilitate more sustainable choices and decrease customer confusion (Dangelico & Vocalelli, Reference Dangelico and Vocalelli2017).

Our results warrant replication. Moreover, given that we asked a hypothetical question online, and previous studies have indicated that findings in online studies might not translate to naturalistic setting (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Pechey, Kosīte, König, Mantzari, Blackwell, Marteau and Hollands2021), extending this work to examine choices in a real-life setting would be justified. For this reason, results should be treated with some caution. Furthermore, our results should not be generalised to all eco-labels; only those which facilitate comparison across products, such as scales or rankings.

Conclusion

Eco-labelling increased the selection of more sustainable food items, compared to both the control condition and social nudge condition. The eco-label was particularly effective among those who were motivated to act sustainably. Pending replication in real-world settings, this suggests that future policy could include eco-labelling and/or a social nudge in both real-world and online settings to reduce meat consumption and meet global climate change targets.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2022.27

Data sharing

The data and analysis code that form the basis of the results presented here are available from the University of Bristol’s Research Data Repository (http://data.bris.ac.uk/data/): https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.2scid2vyz8jh82aj85guyzqrz6

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants which took part in the study.

Funding statement

No external funding outside of the University of Bristol was used (all funding was provided through a personal budget awarded to the supervising author).

Competing interest

No author declares a financial relationship with any organisation(s) that might have an interest in the submitted work and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval

Approved by the Faculty of Science Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol, UK (approval code: 99962).