1. Introduction

In this paper, we ask which factors contribute to the variable development often attested in heritage languages and to what extent these are different from factors affecting monolingual and bilingual L1 acquisition. We address these questions by investigating two phenomena in the Norwegian noun phrase, possessives and double definiteness. Spontaneous data produced by 50 Norwegian heritage speakers in the US are compared to data from previous studies of monolingual Norwegian children and Norwegian–English bilingual children growing up in Norway.

The factors discussed are frequency, complexity/economy, and structural similarity/difference between the two involved languages. The effect of frequency has a central place in language acquisition studies and can be said to be a cornerstone of constructivist theories (e.g., Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003). Nevertheless, frequency has been shown to have its limits (e.g., Roeper, Reference Roeper, Gülzow and Gagarina2007) or only have an effect in combination with other factors such as complexity or economy (e.g., Westergaard & Bentzen, Reference Westergaard, Bentzen, Gülzow and Gagarina2007). In this paper, we treat frequency as a relative concept, in that we only use it to compare the distribution of variants of the same linguistic property (i.e., frequency in a local sense, rather than a global sense). With respect to complexity, we use it as a general term to refer to any aspect of the grammar that can be described as complex, including syntactic movement or the presence of extra morphology (e.g., definiteness marking). The term economy, on the other hand, we use in a more restricted sense to refer to syntactic movement or structure building (cf. section 2.1). Previous findings suggest that monolingual acquisition is constrained by (an avoidance of) complexity, while adult heritage language is largely influenced by frequency (Anderssen & Westergaard, Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010; Westergaard & Anderssen, Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015), and the results of the current study point in the same direction. A third factor is related to the structural similarity/difference between the two languages of bilinguals. In this paper, we focus on the impact of the majority language in a heritage language situation, considering the familiar phenomenon of cross-linguistic influence (CLI), on the one hand, and what is referred to as cross-linguistic overcorrection (CLO) (Kupisch, Reference Kupisch2014), on the other. The former refers to a situation where the dominant language influences the heritage language in a direct way, causing the speaker to use structures that are the same in the two languages, while the latter denotes a situation where this influence is indirect, resulting in a preference for a particular form in the heritage language that is different from that in the majority language. In the current study, we find that the heritage speakers can be divided into two groups, one affected by CLI and the other by CLO, the latter with a somewhat higher proficiency. Thus, different behaviours attested in heritage speaker data are argued to be the result of attrition: With decreasing proficiency in the heritage language, speakers will become increasingly unable to inhibit structures from the dominant language and thus be more affected by CLI. Furthermore, we offer a tentative explanation of CLO as ‘over-inhibition’ of structures in the dominant language, also affecting similar structures in the heritage language.

The paper is organized as follows: In the next section, we provide some background information for this study, while section 3 is an overview of some previous research on acquisition and heritage language. In section 4 we formulate our research questions, and section 5 provides a description of the corpus and participants. The results and analysis of the heritage language data are presented in section 6, which is followed by a discussion of the findings in section 7. Section 8 is a brief conclusion.

2. Background

2.1. First language acquisition

Before we describe the Norwegian DP phenomena, we briefly outline our view of first language acquisition, as this will clarify some of the considerations of complexity below. We follow a structure-building approach to L1 acquistion, which is in line with recent (generative) models such as organic grammar (Vainikka & Young-Scholten, Reference Vainikka and Young-Scholten2011) or the micro-cue model (Westergaard, Reference Westergaard2009, Reference Westergaard2014); see also Clahsen (Reference Clahsen1990), Clahsen, Eisenbeiss and Vainikka (Reference Clahsen, Eisenbeiss, Vainikka, Hoekstra and Schwartz1994), Clahsen, Eisenbeiss and Penke (Reference Clahsen, Eisenbeiss, Penke and Clahsen1996), Duffield (Reference Duffield2008). According to these models, the full syntactic clause structure is not innate, and it may differ across languages as a result of the acquisition process. Children are assumed to gradually build syntactic structure, based on an interaction of universal principles and input from the specific language(s) they are acquiring. In this process, economy plays a crucial role, in that children are argued not to build any more structure than is required by the primary linguistic data; nor do they move elements to higher positions in the structure unless there is clear evidence for this in the input. This means that young children will avoid complexity (syntactic movement and building more structure) and that complex constructions will be acquired somewhat later than less complex ones.

2.2. The structure of possessives and modified definites in Norwegian

Possessives in Norwegian may be pre- or post-nominal (N-POSS or POSS-N), as shown in (1). Double definiteness in the Norwegian Determiner Phrase (DP) refers to the fact that, while unmodified definite noun phrases only require one definiteness marker, a suffixal article (2), modified definite noun phrases have to include two, as a prenominal determiner must be added in these contexts (3).Footnote 1,Footnote 2

(1)

(2)

(3)

Numerous analyses have been proposed to account for Norwegian DPs, and while many issues are unresolved, there appears to be some consensus on the basic order of elements, represented in the (very simplified) structure in (4).

(4)

According to (4), the Norwegian DP includes two determiner positions, one located above (DET) and one below (DEF) the adjectival projection (e.g., Taraldsen, Reference Taraldsen, Mascaró and Nespor1990). The prenominal determiner is associated with the former position, while the definite suffix is associated with the latter (e.g., Vangsnes, Reference Vangsnes1999; Julien, Reference Julien2005; Anderssen, Reference Anderssen2006). The possessive is located above the base position of the noun, but below the definite suffix. As a result, prenominal possessives do not (have to) involve any syntactic movement, as they reflect the basic order of the two lowest phrases in the hierarchy (5).Footnote 3

(5)

Postnominal possessives, on the other hand, always involve movement of the noun across the possessor to merge with the definite suffix (6). Thus, the postnominal possessive construction could be considered to be syntactically more complex than the prenominal structure, as has been argued by Anderssen and Westergaard (Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010).

(6)

There is a similar difference between unmodified and modified definites. In the unmodified case, the noun moves leftward to merge with the definite suffix (as in (6), but without the possessive). In modified definites, however, moving and merging the noun with the definite suffix is accompanied by building more structure (the higher Determiner Phrase and an Adjective Phrase), illustrated in (7).

(7)

Thus, for both possessives and definiteness marking there are two options available, one more complex than the other: Postnominal possessives are more complex than prenominal ones because of syntactic movement, and according to the structure-building approach taken in this paper, modified definite structures are more complex than unmodified definites, as they involve building more syntactic structure. There is also an important difference between these two DP phenomena, as the choice of word order in possessives is dependent on pragmatics, while the inclusion of the prenominal determiner is obligatory in (most) modified structures and ungrammatical in unmodified ones (more on this below).

2.3. The use and distribution of possessives and modified definites

The prenominal possessive construction generally yields a contrastive interpretation of the possessor, while the possessive relationship is backgrounded (topical/given) in the postnominal possessive construction. This is reflected in the stress pattern, as the possessor receives prominence in prenominal structures, while the noun is generally stressed in postnominal ones; see (8)-(9).

(8)

(9)

There are also clear quantitative differences between the two word orders, in that the postnominal possessive construction is much more frequent than its prenominal counterpart. Anderssen and Westergaard (Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010, p. 2581) provide an overview of the distribution of pre- and postnominal possessives produced by eight adults in an acquisition corpus collected in Tromsø (Anderssen, Reference Anderssen2006), showing that they produce 65–93% postnominal possessives, with an average of 75% (851/1135). A very similar distribution is found in adult-to-adult conversations of Oslo speech in the NoTa corpus (http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nota/oslo/index.html) (N = 166), where 72.9% (1883/2583) are postnominal (Westergaard & Anderssen, Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015).

While modified definite DPs must generally appear with two definiteness markers in Norwegian, there are some exceptions to this requirement. Definite DPs involving modifiers that themselves inherently express uniqueness or limit the number of possible referents, e.g., første “first”, are grammatical both with and without the prenominal determiner (10), and the modifier hele “whole” is in fact ungrammatical with a definite determiner (11).

(10)

(11)

Considering the distribution of the two expressions of definiteness more closely, we find a large discrepancy in frequency: While the definite suffix is highly frequent, the prenominal determiner is attested in spontaneous speech with a relatively low frequency. We illustrate this in Table 1, which displays the distribution of the prenominal determiner and the suffix in randomly selected samples from two corpora: child-directed speech from one file in the Tromsø child language corpus (Anderssen, Reference Anderssen2006) and two files of adult-to-adult conversations in the NoTa corpus (http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nota/oslo/index.html). From left to right the columns show the number of examples of definiteness in unmodified structures (N-def, e.g., venn-en “the friend”), target-like modified definites without the prenominal determiner (Mod N-def, e.g., første gang-en “the first time”), double definiteness in demonstratives (Dem N-def, e.g., den venn-en “that friend”), and finally double definiteness in modified structures (Det Mod N-def, e.g., den gode venn-en “the good friend”).Footnote 5 As the raw numbers show, there are only 49 examples of double definiteness, out of a total of 326 definite DPs. As the suffix is included in all cases, this means that it is more than 6.5 times as frequent as the prenominal determiner. In addition, only approximately half of the modified definites in Table 1 require double definiteness. Thus, the prenominal determiner is not only less frequent because it only occurs in modified structures, it may also be omitted in certain contexts.

Table 1. Overview of definiteness marking in two samples of spontaneous production, child-directed speech from the Tromsø corpus and the NoTa corpus (http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nota/oslo/index.html) of Oslo speech.

2.4. Complexity, frequency and cross-linguistic similarity/difference

We have just seen how the factors complexity and frequency are manifested in possessives and double definiteness constructions. An additional factor in bilingual situations is CLI, which is inextricably linked to structural similarity. In possessives, the prenominal construction corresponds to the only possible word order in English. With regard to definiteness marking, the prenominal determiner is similar to the English definite article, while the suffix is not found in English. We thus have a similar situation with regard to the two phenomena: Norwegian has two ways of expressing the property, while English only has one. The construction that is shared between the two languages (the prenominal possessive and the prenominal determiner) is the less frequent one in the language that has both. One difference between possessives and double definiteness is that, in the case of possessives, the postnominal structure is both more complex and more frequent while, for definiteness marking, the more complex structure is the less frequent one. Table 2 summarizes how possessives and double definiteness are related to the three factors complexity, frequency and similarity to English.

Table 2. Manifestation of the factors complexity, frequency and structural similarity with English; possessives and double definiteness.

3. Previous research

3.1. Monolingual and bilingual children

The acquisition of possessives

In Anderssen and Westergaard (Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010), three monolingual Norwegian children (age approximately 1;9-3;3) were investigated with respect to the word order produced in possessives. The data were taken from the Tromsø child language corpus (see Anderssen, Reference Anderssen2006 or Westergaard, Reference Westergaard2009). Recall that we have argued that the postnominal possessive construction is more complex than the prenominal one, and it is also more frequent, making up approximately 75%. This makes interesting predictions for acquisition: If children have a preference for the postnominal possessive construction early on, this would indicate that they pay more attention to frequency, while an early preference for the prenominal construction would indicate that children go for the less complex structure first.

Anderssen and Westergaard (Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010) find that the three children produce prenominal possessive constructions (POSS-N) first, and this word order remains predominant also after N-POSS appears. There are also examples in the early child data showing that the POSS-N construction is used inappropriately, i.e., in non-contrastive contexts. This is illustrated in (12), where the adult uses N-POSS and the child replies using POSS-N. Anderssen and Westergaard (Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010) explain this preference by arguing that complexity is a more decisive factor than frequency in early child language; i.e., children avoid syntactic movement and start out with the less complex structure. Nevertheless, the adult distribution (25% vs. 75%) is in place early, shortly after age 2;6.

(12)

Given the findings from monolingual child data, it is to be expected that the preference for prenominal possessors would be even stronger in Norwegian–English bilinguals, due to CLI. Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015) investigate two bilingual children, and they indeed turn out to have the same preference for the prenominal possessive construction. Moreover, this seems to be stronger and persist longer in the bilinguals than the monolinguals.

The acquisition of double definiteness

Research on the acquisition of definiteness has revealed that the definite article is acquired early in Norwegian and Swedish as compared to other Germanic languages such as English or German (Anderssen, Reference Anderssen, Anderssen and Westergaard2007, Reference Anderssen2010; Kupisch, Anderssen, Bohnacker & Snape, Reference Kupisch, Anderssen, Bohnacker, Snape, Leow, Campos and Lardiere2009 for Norwegian; see also the latter as well as Santelmann, Reference Santelmann, Greenhill, Hughes, Littlefield and Walsh1998 and Bohnacker, Reference Bohnacker, Josefsson, Platzack and Håkansson2004 for Swedish). Investigating the child language corpus mentioned above, Anderssen (Reference Anderssen, Anderssen and Westergaard2007) shows that from the age of two, definite suffixes are supplied at approximately 80%. In comparison, Abu-Akel and Bailey's (Reference Abu-Akel, Bailey, Howell, Fish and Keith-Lucas2000) study shows that 60% of nouns produced by English two-year-olds are bare and only 13% include a definite article. The very early acquisition of the definite suffix in Norwegian (and Swedish) has been argued to be due to its prosodic salience. These elements typically represent the unstressed syllable in a trochee, which is prosodically favoured by children (see e.g., Santelmann, Reference Santelmann, Greenhill, Hughes, Littlefield and Walsh1998; Bohnacker, Reference Bohnacker, Josefsson, Platzack and Håkansson2004; Anderssen, Reference Anderssen, Anderssen and Westergaard2007; Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Anderssen, Bohnacker, Snape, Leow, Campos and Lardiere2009). In the previous section, we also argued that the suffix is less complex and more frequent than the prenominal determiner. Thus, it is not surprising that it is acquired early.

The prenominal determiner in modified structures is acquired considerably later. Anderssen (Reference Anderssen, Anderssen and Westergaard2007, Reference Anderssen2012), investigating the same three children as Anderssen and Westergaard (Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010), shows that as much as 49.3% (69/140) of modified definite structures (requiring double definiteness) include only the definite suffix; see (13) (from Anderssen, Reference Anderssen2012, p. 16). Unlike possessive structures, double definiteness is still not used at a target-like level when the recording period ends. Recall from the previous section that the prenominal definite determiner is both structurally complex and infrequent in the input.

(13)

For bilingual Norwegian–English acquisition of double definiteness, we only have data from a small corpus of one child, Emma (Bentzen, Reference Bentzen2000). Contexts in which double definiteness is required are relatively infrequent, and as a result, there are few relevant examples. However, as pointed out in Anderssen and Bentzen (Reference Anderssen and Bentzen2013), this disadvantage is at least partly mitigated by the fact that the developmental pattern is quite clear. Like her monolingual peers, Emma struggles with double definiteness, but her errors are different: 55.6% (10/18) of her modified definites are produced with the prenominal determiner only; see (14) (from Anderssen & Bentzen, Reference Anderssen and Bentzen2013, p. 89).

(14)

As we have seen, both the monolinguals and the bilingual child have problems with double definiteness, but their error patterns differ: While the monolinguals tend to omit the prenominal determiner, the bilingual child typically omits the suffix. Thus, the bilingual child has a preference for the determiner that is similar to the English structure, and this result can be argued to be a case of CLI. It is important to stress here, however, that this does not necessarily mean that all children growing up with English and Norwegian will respond to the bilingual input in the same way. Nevertheless, the fact that this child does produce such structures shows that this is a possible outcome of the bilingual situation, as a pattern such as this one is not attested in monolingual development. Thus, the influence from English makes the child produce a structure that is both more complex and less frequent.

3.2. Heritage speakers

Given the more persistent preference for prenominal possessives in the bilingual child data and the suggestion that this is a result of CLI, Norwegian heritage speakers would be expected to exhibit the same pattern. However, data from 37 heritage speakers investigated by Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015) show the opposite (see below for more information about these speakers): While the proportion of POSS-N in the corpora of non-heritage Norwegian is around 25%, the overall percentage of this construction in the heritage speaker data is only 19.9% (this number includes occasional fixed expressions). With the exception of three individuals who have a preference for prenominal possessives, the remaining heritage speakers display a clear preference for the postnominal possessive construction, producing this word order considerably more than Norwegians speaking the non-heritage variety. Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015) speculate that the three speakers are re-learners of Norwegian.

Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015) interpret their findings in the following way: Complexity is a stronger factor than frequency in all acquisition processes, accounting for the high use of POSS-N (the simpler structure) in the mono- and bilingual children. Bilingual Norwegian–English children, and possibly the adult re-learners, have an additional effect of CLI due to the structural similarity with English. However, once acquired, the complexity of a construction does not play a role. The N-POSS construction is thus no longer vulnerable in the grammar of adult heritage speakers. Furthermore, the high frequency of this construction protects it from attrition.Footnote 6

However, one might ask whether the majority of the heritage speakers are in fact overusing postnominal possessives. The reason for this is that, when certain fixed expressions that may only appear with POSS-N are excluded from the data investigated in Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015), the majority of the heritage speakers hardly produce prenominal possessives at all. This could mean that frequency plays a more important role in (adult) heritage language in that it not only protects a construction from attrition, but also causes more frequent constructions to be generally preferred while less frequent ones are lost.

Some evidence that this could be the case is found in recent data from Italian adult heritage speakers in Germany, studied in Kupisch (Reference Kupisch2014). The construction investigated is the order of adjectives in relation to the head noun. In Italian, N-ADJ is the generally preferred word order and by far the more frequent one, while ADJ-N is possible in certain cases, often with specific meanings (see also Cardinaletti & Giusti, Reference Cardinaletti, Giusti, Anderssen, Bentzen and Westergaard2010), as illustrated by the examples in (15)-(17) (from Kupisch, Reference Kupisch2014, p. 223). In German, on the other hand, only the prenominal order is possible. This means that this word order phenomenon is very similar to possessives in Norwegian–English bilingualism: one language has only one word order, while the other has two, with the word order that is different from that of the other language being much more frequent. Furthermore, it is commonly argued that the N-ADJ order is more complex than ADJ-N, in that it is derived by N-movement across the adjective.

(15)

(16)

(17)

While monolingual Italian children have been found to be generally target-consistent with respect to adjective/noun word order from early on (Cardinaletti & Giusti, Reference Cardinaletti, Giusti, Anderssen, Bentzen and Westergaard2010), some bilingual children (speaking another language with only ADJ-N) have been shown to overuse the prenominal adjective position at an early stage (Bernardini, Reference Bernardini and Müller2003; Rizzi, Arnaus Gil, Repetto, Müller & Müller, Reference Rizzi, Arnaus Gil, Repetto, Müller and Müller2013). Kupisch (Reference Kupisch2014) finds the opposite preference in Italian adult heritage speakers in Germany: In an online task, these speakers over-accept the postnominal adjective position, i.e., the more frequent word order.Footnote 7 Kupisch (Reference Kupisch2014) suggests that adult bilinguals are different from bilingual children in that they tend to over-emphasize differences between their two languages. This phenomenon is the inverse of CLI, and Kupisch refers to it as cross-linguistic overcorrection (CLO).

In the present study, we investigate the question whether the majority of the Norwegian heritage speakers could be overusing the postnominal possessive construction, the more complex but also the more frequent one. If so, like the Italian heritage speakers in Germany, they could be paying more attention to the differences between their two languages and thus be affected by CLO.

4. Research questions and predictions

Given previous findings from Norwegian heritage speakers with respect to possessive constructions (Westergaard & Anderssen, Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015) and data from monolingual and bilingual children, we ask the research questions in (18) and make the corresponding predictions in (19):

(18) Research questions

a. Do Norwegian heritage speakers use pre- and postnominal possessives in a target-like way, and if not, do they show signs of CLI or CLO?

b. Do Norwegian heritage speakers produce target-like modified definites, or do they omit one of the expressions of definiteness?

c. Is there a correlation between the preference for word order in possessives and a preference for one of the determiners in the production of modified definites, in accordance with the factors CLI and CLO?

d. Is there a correlation between general proficiency in Norwegian and heritage speakers’ preferences for possessive word order and (double) definiteness?

(19) Predictions

a. We expect most heritage speakers to have a preference for N-POSS, the more frequent word order in Norwegian, but also the one that is different from English. We expect a subset of the heritage speakers to favour POSS-N.

b. Given the complexity and infrequency of double definiteness and the difficulties attested in acquisition, these structures should constitute a challenge for heritage speakers, and we expect them to display a tendency to drop either the prenominal determiner or the suffix.

c. We expect heritage speakers to have a preference for either the typically Norwegian structures or the typically English structures: Those who mainly produce N-POSS should drop the prenominal determiner, as this results in structures that are typically Norwegian, while those who have a tendency to produce POSS-N should drop the suffix, i.e., they should produce structures that are similar to English.

d. Preferences should correlate with language proficiency, in that speakers who prefer the typically Norwegian alternatives should generally have a higher proficiency.

5. The data and participants

The heritage speakers investigated in our study are a group of Norwegian-Americans in the USA, more specifically informants who were interviewed in connection with the project NorAmDiaSyn. The heritage speakers have been recorded in conversation with an investigator from Norway or another heritage speaker. Some of the interviews have been transcribed and make up the Corpus of American Norwegian Speech (CANS) (Johannessen, Reference Johannessen and Megyesi2015), which is available on the website of the Text Lab, University of Oslo. The study is still ongoing, and new interviews are continually added to the database. For general information on Norwegian immigration to the USA and the background of these Norwegian speakers, see Haugen (Reference Haugen1953); Johannessen and Salmons (Reference Johannessen, Salmons, Johannessen and Salmons2015); Lohndal and Westergaard (Reference Lohndal and Westergaard2016).

This study is based on the current corpus of 50 heritage speakers. Some of these (24) are identical to the speakers that were investigated in Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015), where the data on possessives were extracted by listening to the recordings, as they had not been transcribed at the time. In order to have proper comparisons between possessives and double definiteness in the current study, we have extracted all the heritage speaker data of both constructions from the transcriptions.

The informants are quite old (around 70–100 years of age) and mainly second- to fourth-generation immigrants, who grew up speaking Norwegian at home with their parents and grandparents. They generally speak rural East Norwegian dialects, corresponding to the area that the majority of immigrants came from. A question that naturally arises is whether possible differences between the heritage speakers and the present-day corpora (from Tromsø and Oslo) could be due to dialect differences. This issue is discussed in Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015), who used the Nordic Dialect Corpus (Johannessen, Priestly, Hagen, Åfarli & Vangsnes, Reference Johannessen, Priestley, Hagen, Åfarli, Vangsnes, Jokinen and Bick2009) to compare the relevant dialects. While it is impossible to know exactly what the input to these heritage speakers was like, Westergaard and Anderssen conclude that dialect differences are an unlikely cause of differences regarding possessives. To our knowledge, there are no relevant dialect differences with respect to double definiteness.

Most of the heritage speakers did not learn English until they started school around the age of six, and they may therefore be characterized as successive bilinguals. The home language was Norwegian, but they generally had little opportunity to use Norwegian in the community, and English has been the dominant language for these speakers throughout their adult lives. They have not passed on the language to their own children, and they rarely speak Norwegian today, mainly due to the very limited number of available conversation partners. Furthermore, most of these speakers have never learned to read and write Norwegian and only a few of them report that they have any connection with Norway and Norwegians. As mentioned above, Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015) speculated that the three speakers who produced high proportions of prenominal possessives were ‘re-learners’, based on the observation that they were able to read Norwegian and were actively trying to improve their heritage language. Given the (relatively sparse) background information on individual speakers in the corpus, it is not possible to make such a distinction in the larger group of speakers. Instead we introduce a measure of proficiency (more on this below).

The profile of these heritage speakers is in some sense typical of other heritage populations, in that they have experienced a language shift around school age. However, they are also different from most heritage populations that have been studied in the literature, due to the – in some cases – extreme lack of use of the heritage language in recent years as well as their advanced age. For these reasons, it is likely that whatever differences we may find between these speakers and speakers of non-heritage Norwegian should be due to attrition (representational deficits and/or processing difficulties) rather than arrested development. This is also supported by the fact that both possessive distribution and double definiteness are phenomena that fall into place in child language relatively early, around or shortly after the age of three.

6. Results

6.1. Raw data: Possessives and modified definites

In this section, we provide a description of the results in terms of raw data, while the statistical analysis is provided in 6.2. For possessive constructions, the CANS corpus was searched for all cases of both word orders, N-POSS and POSS-N. For the latter, we disregarded fixed expressions where the prenominal possessive construction is obligatory (altogether 40 examples), e.g., i mi tid “in my time”. We also excluded one example that had both a prenominal and a postnominal possessor, the phrase his mor hass “his (Eng) mother his”, where the prenominal possessor is provided in English and the postnominal in Norwegian. We find in total 756 instances of possessive structures in the material (50 speakers, mean 15.2, sd 14.5), of which only 129 were prenominal (17.1%). This is similar to the Westergaard and Anderssen (Reference Westergaard, Anderssen, Johannessen and Salmons2015) finding that the heritage speakers as a group produce somewhat fewer prenominal possessives than speakers of non-heritage Norwegian, for which the percentages in the two corpora studied were 25% and 27.1% (cf. sections 2.3 and 3.2). In relation to research question (a), we can conclude that the speakers generally do not show signs of CLI, i.e., they do not overuse the English-like POSS-N structure. If anything, they overuse the Norwegian-specific postnominal possessives. A closer look at the data reveals that the majority of the speakers (27/50) in fact produce only N-POSS, and that most of the instances of POSS-N are produced by a handful of speakers. This suggests that there is a very strong general tendency for CLO, which we return to in the next section. Individual results for all 50 speakers may be found in Appendix A.

Turning to the use of modified definite DPs, we first provide some overall results. The 50 heritage speakers produce a total of 422 examples of modified definites (mean 8.4, sd 7.7). As we saw in section 2.3, there are some exceptions to the general requirement for double definiteness, in that several frequently used modifiers, such as first or other, allow for the prenominal determiner to be omitted (Mod N-def). A relatively large proportion of the modified definites produced by the heritage speakers turn out to involve such adjectives, which represent 43.8% (185/422). An additional 22% (93/422) of these DPs are produced with double definiteness (Det Mod N-def) in a target-like manner. This makes 65.9% (278/422) of the relevant structures produced by the heritage speakers target-like.

Nevertheless, the total number of errors is fairly high (34.1%, 144/422), indicating that the heritage speakers have problems with double definiteness. The vast majority of these errors involve dropping the prenominal determiner (*Mod N-def, n = 113, 23.7%), while a small proportion involves the omission of the suffix (*Det Mod N, n = 31, 7.3%). Just as for the possessives, we see that this cannot be explained as a result of CLI: the errors that the heritage speakers make are not mainly of the English-like structure (*Det Mod N), but of a more Norwegian-like type with only suffixal definiteness. Again, we find that the English-like errors are produced by a small number of speakers, which will be returned to in the next section. The distribution of the different types of modified definites for all 50 speakers may be found in Appendix A. Examples of the different structures are provided in (20)-(23).

(20)

(21)

(22)

(23)

6.2. Correlations between possessives and modified definites

The raw data in the previous section show little evidence of CLI from English in the heritage speakers’ production. If anything, as a group, the heritage speakers produce fewer English-like possessive structures (POSS-N) and only a small proportion of the double definiteness errors are of the English-like type (*Det Mod N), i.e., dropping the suffix. However, as indicated by the raw data, there is some between-speaker variation for the possessives, with a small number of speakers producing a fairly high number of POSS-N.

Research question (c) addressed whether there is a correlation between type of definiteness error and possessive preference. Since more than half of the speakers produce only postnominal possessives, a regular correlation test is not ideal here (e.g., correlating the proportion of N-POSS structures with the number of definiteness errors). Furthermore, the corpus size for each speaker differs considerably, with the total number of complex DPs produced by each speaker ranging from 1 to 89. The very low counts cannot reveal the word order preference of a speaker, and we have therefore decided to exclude all speakers who produce fewer than 9 possessive structures (22 speakers) in the further discussion. This gives us a group of 28 speakers who clearly divide into two groups: 21 speakers with a strong preference for N-POSS and seven speakers producing a high number of POSS-N. We refer to the former as the Norwegian group, since they have a preference for the structure that only exists in Norwegian, and the latter as the English group. Table 3 gives an overview of the production of possessives in the two groups, showing that the speakers in the Norwegian group produce 86–100% postnominal possessives (mean 96%), while the range for the English group is 0–55% (mean 33%). The table also gives the mean total of these speakers’ production of modified definite DPs, showing that both groups have similar total counts for these structures.

Table 3. Overview of the production of possessives, two groups of Norwegian heritage speakers.

We thus have two groups with comparable mean values for the total number of possessive and modified DPs, defined by their choice of possessive structure. As shown in section 2.2, previous corpus analysis of non-heritage Norwegian shows that native speakers display a relatively stable proportion of N-POSS around 75%. This means that both groups seem to differ in their production of possessives from Norwegian speakers in Norway: the Norwegian group produces almost exclusively N-POSS and the English group produces a considerably lower proportion than non-heritage speakers. Thus, target-like speakers seem to be absent from our sample, as there is a gap in the native range of 65–85% N-POSS. A chi-square test shows that the Norwegian group uses N-POSS significantly more often than 75% (482/492, χ2 = 138.42, df = 1, p < .001), while the English group produces this word order significantly less often (69/172, 111.63, df = 1, p < .001).

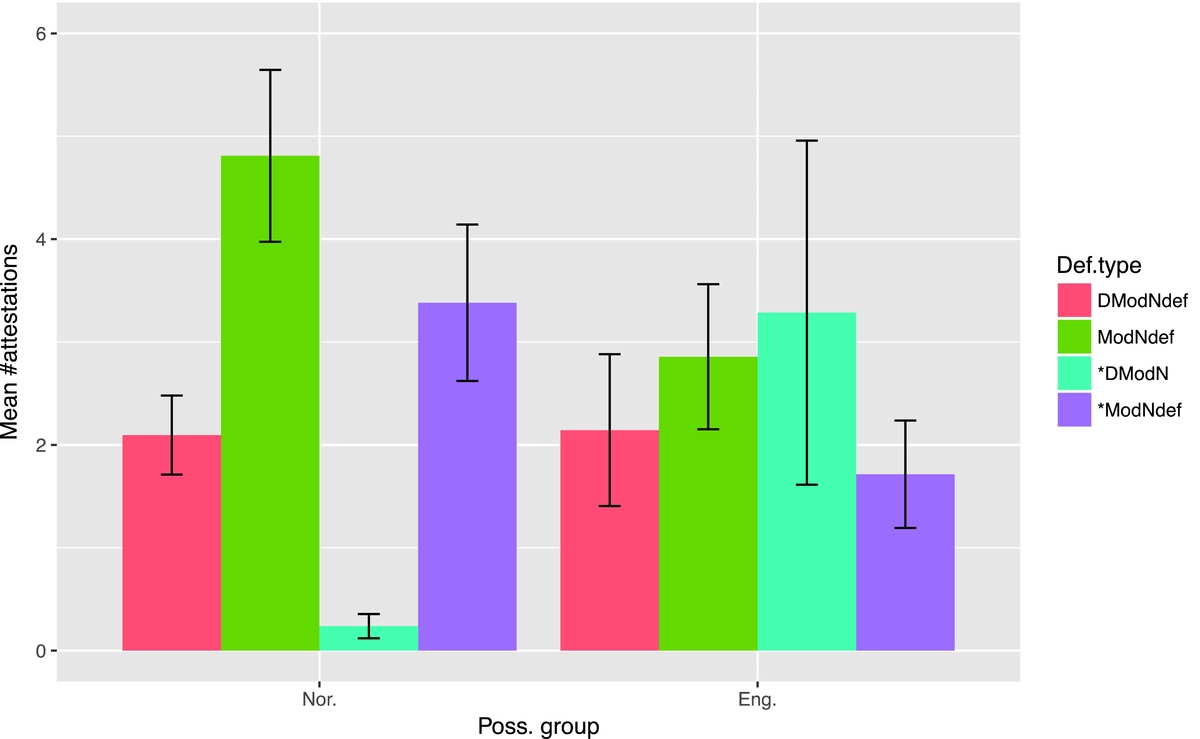

Furthermore, we find that the Norwegian and English groups differ in their preference for type of modified DP: the English-like definite structure (*Def Mod N) is almost exclusively found in the English group. Figure 1 shows the average number of attestations for the four different types of modified definite DPs across the two groups: the two grammatical ones (double definiteness, grammatical determiner drop) and the two ungrammatical ones (suffix drop, ungrammatical determiner drop); see Appendix B for further details.

Figure 1. The production of modified definites by two groups of Norwegian heritage speakers, distributed across two grammatical structures (double definiteness, determiner drop) and two ungrammatical structures (suffix drop, determiner drop). Error bars represent one standard error above and below mean (with within-subject adjustments).

As can be seen in the graph, the participants in the two groups on average produce the same number of double definites, but otherwise, they clearly differ in their production pattern. More importantly, the speakers in the two groups make different types of errors: While the English group tends to drop the suffix, the speakers in the Norwegian group are more likely to drop the prenominal determiner, showing preferences for the English and Norwegian structures respectively. In fact, the Norwegian group makes almost no errors of the English-like type (dropping the suffix, *Det Mod N), while this is the most common definite DP produced by the English group. Note that the Norwegian group also produces a higher number of grammatical structures without the prenominal determiner (where adding it would also have been grammatical), thus indicating a dispreference for the English-like structure, both in their grammatical and their ungrammatical production.

In analysing the results, we performed a mixed-effects Poisson regression analysis in R using lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015). The dependent variable was the number of attestations of modified definites. Possessive group (Norwegian vs. English) and definiteness type (the four attested definite structures) were the predictors, as well as the interaction between these two predictors. The model included a random intercept for speaker. The variables were dummy coded, and the double definite form (Det Mod N-def) for the Norwegian group was set as the intercept. See Appendix C for the full regression table.

The model revealed that the Norwegian group produces significantly more grammatical modified definite DPs without the prenominal determiner (Mod N-def) than double definite forms (Det Mod N-def) (ß = 0.83, SE = 0.18, p < .001), and significantly less suffix drop (*Det Mod N) than double definite forms (ß = –2.17, SE = 0.47, p < .001). The ungrammatical sentences where the prenominal determiner is dropped (*Mod N-def) are also significantly more frequent than the double definite forms (ß = 0.48, SE = 0.19, p = .011). There was no main effect of group, i.e., the two groups did not differ in their production of double definiteness. The only significant Group-Type interaction is for suffix drop (*Det Mod N, ß = 2.6, SE = 0.57, p < .001). That is, speakers in the English group produce significantly more *Det Mod N structures than the Norwegian group (based on expectation from their Det Mod N-def production). Overall, the English group shows no clear signs of a system in the production pattern of the modified definites; instead, they seem to randomly alternate between the four possible choices. This is very different from the Norwegian group, who show a strong preference for avoiding the prenominal determiner, i.e., producing mainly (*)Mod N-def. It should be noted that the English group produces numerically fewer grammatical and ungrammatical structures where the prenominal determiner is dropped ((*)Mod N-def) than the Norwegian group, but the differences do not reach statistical significance (p = .15 for Mod N-def and p = .099 for *Mod N-def).

This shows that predictions (b) and (c) are borne out: the heritage speakers all have problems with producing target-like double definites, but they choose different strategies to avoid this complex structure. The speakers who have a preference for English-like possessive structures (the English group) generally drop the suffix, while the speakers who overuse the Norwegian-specific possessive (the Norwegian group) drop the prenominal determiner.

6.3. Language proficiency

The final research question (d) relates to general proficiency in the heritage language. Unfortunately, no proficiency test has been carried out on the speakers in the CANS corpus, and it is unclear how one could measure proficiency in this group of relatively old speakers. One possibility could be to use background information as a proxy, but the background data on the 50 speakers in the corpus is very sparse and not collected in such a way that it facilitates comparison. There are three factors listed on the biographical information forms that could potentially be important: literacy in Norwegian, contact with Norway, and age of acquisition of English. However, the responses made by the speakers are not standardized and are reported as e.g., “little, some, no, yes, often” etc. for the first two factors, and generally as “school age” and “before school age” for the third factor. Furthermore, the responses made by the speakers in the English group do not seem to be any different from the other group.

Another possibility is to examine how (non-)target-like the speakers are with regard to other structures and use this as a measure of proficiency. One such measure that we may use for this purpose is the speakers’ overall non-target-consistent production of double definiteness, i.e., the production of the structures *Mod N-def and *Det Mod N (cf. the previous section). Another possible measure is the individual speakers’ production of gender forms. Grammatical gender has been shown to be vulnerable in heritage languages, e.g., Russian (Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2008; Rodina & Westergaard, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2017), and this has also been attested for the current population of heritage Norwegian speakers (investigated in Lohndal & Westergaard, Reference Lohndal and Westergaard2016).

Considering the total number of errors produced in modified definites, we find that the speakers in the English group produce more errors than the speakers in the Norwegian group: 5 compared to 3.6 on average per speaker. This difference is approaching statistical significance (ß = 0.696, SE = –0.36, p = .053, see Appendix D for a full summary of the mixed effects logistic regression).

We also find that the speakers in the English group on average make more gender errors. When calculating the number of errors, we excluded cases where the Masculine article was used for a Feminine noun, as there is considerable variation in this context also in non-heritage Norwegian. The results reveal that the speakers in the Norwegian group on average produced 2 gender errors, while the speakers in the English group made 4 errors per speaker. However, the overall numbers are low, and the variation between speakers within the two groups is large, and this difference does not turn out to be significant (ß = 0.4, SE = .46, ns).

Based on the overall error counts, we may cautiously conclude that there is a slight difference in proficiency between the English and the Norwegian groups. The results suggest that speakers with a relatively low proficiency in the heritage language have a preference for structures corresponding to their dominant language, while speakers with a higher proficiency tend to overuse the typical heritage language structures.

7. Discussion

The data analysis in the previous section has provided answers to the four research questions, and the corresponding predictions are all borne out:

(a) The heritage speakers are not target-consistent with respect to the production of possessives, but can be divided into two groups, one with a preference for N-POSS (the Norwegian group), the other overusing POSS-N (the English group).

(b) The heritage speakers also have problems with double definiteness, often producing modified definites where one exponent of definiteness is dropped, either the prenominal determiner or the suffix.

(c) There is a statistically significant correlation between the production of the two structures, in that the Norwegian group has a preference for the typically Norwegian-like structures (N-POSS, modified definites without the determiner), while the English group overuses the English-like structures (POSS-N, modified definites without the suffix).

(d) The speakers who have a preference for the typically Norwegian-like structures (the Norwegian group) have a somewhat higher proficiency in the heritage language than speakers who overuse structures from the dominant language (the English group).

These results lead to a further question: Why should English-like properties and Norwegian-like properties go together in these groups of heritage speakers? An obvious answer for the English group is that they are affected by CLI from their dominant language, a not unusual finding in bilinguals. It is more surprising that overuse of the two Norwegian-like properties go together, especially since they sometimes lead to non-target-consistent production, and as such this cannot only be a sign of high proficiency. We would like to argue that this is the result of what Kupisch (Reference Kupisch2014) refers to as CLO; that is, a tendency to choose structures that are different in the two languages. It should be noted that in Kupisch's study, CLO is also attested in highly proficient speakers.

We would like to offer a tentative explanation for the phenomenon of CLO: It is well known that when bilinguals speak one of their languages, they need to inhibit the other (e.g., Hartsuiker, Pickering & Veltkamp, Reference Hartsuiker, Pickering and Veltkamp2004; Martin, Dering, Thomas & Thierry, Reference Martin, Dering, Thomas and Thierry2009). In the case of possessives in English and Norwegian, for example, with two options in one language and only one in the other, a heritage speaker of Norwegian will prevent the influence of English by inhibiting POSS-N. This, we argue, may also affect the heritage language, in such a way that the speaker is at the same time inhibiting this (perfectly possible) structure in Norwegian. This strategy results in an overuse of the other word order in the heritage language, in this case N-POSS. That is, an ‘over-inhibition’ of the structure that is similar in the two languages leads the speaker to choose the word order that is different from that of the dominant language; in other words, to hypercorrect by overusing the structure that is typical of the heritage language. However, the ability to inhibit the dominant language will be dependent on the speaker's proficiency in the heritage language. Thus, with lower proficiency, it should be harder to inhibit the influence from the majority language, and this would account for the effect of CLI in this case.

If we imagine that these heritage speakers are on a cline towards language attrition, it is interesting to compare their production with that of children. Starting with the English group, it is clear that their behaviour is similar to that of the bilingual child(ren) discussed above. In both cases, the relevant speakers are affected by CLI and, in modified definites, the impact of the other language (English) seems to override both complexity and frequency. For the bilingual children, this is a step in the development towards a more target-like grammar, but this seems to be a step in the opposite direction for the adult speakers, indicative of a loss of proficiency in the heritage language.

The other group of heritage speakers (the Norwegian group) favours the more frequent structures. This entails that their preferences diverge from those of monolingual and bilingual children for possessives while, for modified definites, they have a preference for the same structure as monolingual children, i.e., the suffix. Speakers in the Norwegian group are also somewhat more proficient, which indicates that frequency effects and CLO are typical characteristics of the language of (relatively proficient) heritage speakers.

A frequently asked question is whether heritage speakers are different from non-heritage speakers because the input that they have been exposed to is not the same as that of learners of the non-heritage variety, or because they have processed the input in a divergent manner due to limited input or the bilingual situation itself. Unfortunately, we do not have available data about these speakers’ input, so we cannot answer this question. But regardless of whether this is a shift that has taken place in this generation or the previous one, the current grammar of the majority of these speakers (the Norwegian group) appears to contain only one word order, N-POSS. That is, the variation in the non-heritage variety seems to have been lost. A similar loss of word order flexibility is reported in Namboodiripad, Kim and Kim (unpublished manuscript) for Korean heritage speakers (with English as the majority language). Given that young Norwegian children have a preference for POSS-N, it seems clear that the behaviour that we see with possessives in the Norwegian group of heritage speakers cannot be the result of incomplete acquisition (in this or the previous generation), as arrested development should result in POSS-N structures being favoured (i.e., the structure preferred by monolingual and bilingual children). However, this possibility cannot be excluded for the English group. When it comes to modified definites, on the other hand, the preferred option for monolingual children (the suffix) corresponds to the non-target structures produced by the majority of heritage speakers, i.e., the Norwegian group, while the production of the English group corresponds to the production of the bilingual child (a preference for the prenominal determiner). These patterns could be compatible with arrested development if we were to assume that the Norwegian group grew up with monolingual input until the age of 6, and the speakers in the English grew up as simultaneous bilinguals. However, the available background data do not align with such a distinction between the groups, and we therefore find it more likely that the attested differences are due to different stages of attrition, the English group having advanced more in that direction.

Relevant to this discussion is the approach taken in Putnam and Sánchez (Reference Putnam and Sánchez2013) and Yager, Hellmold, Joo, Putnam, Rossi, Stafford and Salmons (Reference Yager, Hellmold, Joo, Putnam, Rossi, Stafford and Salmons2015), where heritage grammars are taken to be complete grammars, capable of change and reanalysis, rather than flawed, incomplete systems. According to this view, heritage bilinguals are assumed to be at different stages on a sliding spectrum, where they progressively transfer or reassemble (functional) features from the L2 into the L1. The extent to which this occurs is dependent on the degree of activation of the heritage language rather than the frequency of the relevant lexical items (though this must to some extent be dependent on, and a reflection of, exposure and use). In terms of the current study, the Norwegian group would then be the least affected and the English group the most affected by this development. The slide down the spectrum in this case would then be reflected in the degree of CLI as manifested by the use of English-like structures, POSS-N and omission of the suffix in modified definite DPs. However, this approach does not account for the exclusive use of the word order that is different from the English one in the most proficient group, i.e., our findings of CLO. As discussed above, this might be the result of ‘over-inhibition’ of the English-like structures with a simultaneous and ensuing ‘over-activation’ of the exclusively Norwegian ones, both for possessives and modified definites. Thus, CLO could be seen as both similar and different from CLI – similar in the sense that it is related to co-activation of the two grammars, but different in that it represents the end of the spectrum where proficiency in the heritage language is relatively high and therefore leads to the opposite result, viz. CLI.

For both phenomena that we have considered here, the structures that are the most frequent are also the more typical Norwegian structures. For this reason, it is difficult to separate the effect of frequency from CLO. It might be that CLO only occurs in situations where the structure that is different from the one in the dominant language is also more frequent, or it might be that what looks like an effect of frequency is in fact the result of CLO only. In order to test this, it would be necessary to study properties where low frequency coincides with structural difference in the heritage language.

8. Concluding remarks

This paper has investigated two syntactic phenomena of Norwegian spoken by adult heritage speakers in the US, word order in possessives and double definiteness in modified DPs. In both cases, Norwegian has two options, while English only has one. The findings show that the heritage speakers can be divided into two different groups: One with a preference for the typically Norwegian-like structures (the Norwegian group) and another overusing the English-like structures (the English group). We also find that the latter group has a slightly lower proficiency in the heritage language, and we argue that the English group is influenced by cross-linguistic influence (CLI), while the Norwegian group is affected by what is referred to as cross-linguistic overcorrection (CLO) (Kupisch, Reference Kupisch2014). A tentative explanation of these phenomena in terms of co-activation of the two grammars is proposed: While CLI is caused by an inability to inhibit structures from the dominant language (increasing with decreasing proficiency), CLO is the result of ‘over-inhibition’ of majority language structures, also affecting similar structures in the heritage language and thus leading to an over-activation of structures that are different from the dominant language.

Appendix A. Overview of possessives and double definiteness, CANS (n = 50).

Appendix B. Average number of attestations of modified DPs across two groups of Norwegian heritage speakers.

Appendix C. Mixed effects model for definiteness type and possessive group.

Appendix D. Mixed effects model for Proficiency (definiteness)