The age–crime curve shows that the majority of crime is committed by those aged below 40, with a peak incidence in the 20s (Reference McAra, McVie, Maguire, Morgan and ReinerMcAra 2012). Consequently, forensic mental health service provision is geared to looking after the needs of younger men and women. Comparatively little is written about the clinical needs of older offenders with mental disorder. In the UK, the Equality Act 2010 made it a legal requirement for mental health services to promote age equality, with an emphasis on age appropriateness. The size of the older adult population is increasing, which may lead to an increase in the number of older forensic patients; forensic services will have to adjust in order to meet the Department of Health recommendations relating to the ‘specific needs’ of these people.

Characteristics of older people

Who is ‘older’?

The definition of ‘older’ is far from clear (Reference Yorston and TaylorYorston 2006). Back in 1875, The Friendly Societies Act defined old age as 50 years and above, but a more appropriate definition today is probably the United Nations cut-off of 60 years and above. In 2013, the population estimate for the UK was over 64 million people, more than 18 million of whom were over 55 (Office for National Statistics 2013a). The population aged over 60 was projected to increase from 23% to nearly 29% in 2034 and 31% in 2058 (Office for National Statistics 2013b). However, biological age is more important than chronological age when considering age-related needs (Reference Yorston, Dening and ThomasYorston 2013), taking into account that ageing affects people differently and that there is now no such thing as ‘normal ageing’. There is great variation in its effects, with advances in medicine and healthier lifestyles changing the ageing process, and government policy shifting the ‘retirement line’ (Mental Health Foundation 2009). Also, older people are a diverse group in terms of their social and emotional needs, well-being and lifestyle.

Offending

Older offenders fall into three distinct categories: those who are old when they commit their first offence (first-time offenders), those whose offending started when they were much younger (recidivists) and those who offended young and have remained in prison on a long sentence (long-sentence prisoners) (Reference Ulmer, Steffensmeier, Beaver, Barnes and BoutwellUlmer 2014). In a US sample of prison inmates over the age of 55, Reference Steffensmeier, Motivans, Rothman, Dunlop and EntzelSteffensmeier & Motivans (2000) found that first-time offenders represented 41%, recidivists 46% and long-sentence prisoners 13%. These categories are important determinants of how these groups are likely to present to mental health services, what their treatment needs are and the chances of subsequent recidivism.

Table 1 summarises the offence types in a sample of older people. Sexual offences account for the majority of offences committed by sentenced older men in prisons in England and Wales. Reference WahidinWahidin (2004) notes that, in a sample of women aged over 60 in prisons in England and Wales, the most prevalent offences were violence against the person, sexual offences and drug offences. Research on reoffending rates in older offenders is sparse, although some studies have shown low rates (Reference HansonHanson 2002). Reference O'Sullivan and ChestermanO'Sullivan & Chesterman (2007) found that 38% of older people detained in a secure hospital had committed homicide, 25% had committed attempted murder and 7% had committed sexual offences. These figures correlate with the pattern of violent offending in the USA described by Reference Lewis, Fields and RaineyLewis et al (2006) in a study of older defendants charged with a violent offence and referred for psychiatric evaluation. This difference between prison and forensic psychiatric populations may reflect legal strategies by defence solicitors and/or a stronger relationship between mental disorder and violence in older people.

TABLE 1 Breakdown of offences committed by older people in the UK and USA

Mental disorder and behavior

Older offenders frequently have concurrent cognitive, emotional, social, interpersonal, behavioural, physical and psychiatric morbidities (Reference Tomar, Treasaden and ShahTomar 2005) that are different from those in younger offenders. They are often unemployed and have a poor educational background and significant criminal and psychiatric histories (Reference Lewis, Fields and RaineyLewis 2006; Reference Yorston and TaylorYorston 2006). These factors are believed to increase the risk of verbal and physical aggression displayed by older people residing in institutional settings (Reference Bowie, Moriarty and HarveyBowie 2001).

Table 2 gives an overview of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in older offenders from research undertaken in a number of settings in the UK, USA, Israel and Sweden. From the sources listed in Table 2 we noted that a higher rate of psychiatric disorders was found in older offenders in prison than in younger offenders in prison or older people in the community. There was no difference in the rates of psychiatric disorders between older people who committed their first offence before or after the age of 60. Although older women are represented in the data, men greatly outnumber women, as expected. The only significant finding reported for older women was from a prison population and it noted that older women were more likely to have psychosis than younger women.

TABLE 2 Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in offenders in different settings

Reference Tomar, Treasaden and ShahTomar et al (2005) found diagnoses of schizophrenia and dementia in three out of every four homicide perpetrators in a sample of older offenders who had been referred to a medium secure forensic unit in the London area over a 13-year period.

Reference Fazel, Gunn and TaylorFazel (2014: p. 527), applying to 2004 demographic data the estimate that 5% of older prisoners have a psychotic illness, calculated that ‘at any one time about 70–80 […] sentenced male prisoners aged 60 or over in England and Wales would be psychotic, almost all with a depressive psychosis’. Reference Fazel, Gunn and TaylorFazel (2014) also reported that the prevalence of dementia among male sentenced prisoners aged over 60 in the prison population in England and Wales was only 1%, which is significantly lower than in other settings. This could be due to several factors, including successful identification of prisoners with dementia leading to early transfer to hospital, low rates of offences by people with dementia, lower case progression and conviction rates, or undiagnosed depression and dementia (Reference Curtice, Parker and WismayerCurtice 2003; Reference Fazel, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and DeningFazel 2008).

Personality disorder has been found in between 17 and 29% of older men who attend for psychiatric evaluation (Reference Koenig, Johnson and Bel lardKoenig 1995; Reference ShahShah 2006). Reference Fazel, Hope and O'DonnellFazel et al (2001a) found that in older prisoners in England and Wales the total prevalence of personality disorder was 30%, antisocial personality disorder accounting for 8.3%. Reference Fazel, Hope, O'Donnell and JacobyFazel et al (2002) note that in older sex offenders, personality factors were more relevant than mental illness or organic brain disease. In a qualitative survey of forensic psychiatrists and psychologists (Reference Van Alphen, Nijhuis and OeiVan Alphen 2007), respondents reported that sexual offences were the most common offence type among older patients with antisocial personality disorder. A large proportion (97.1%) said that older people with antisocial personality disorder tended to justify their behaviour. Interestingly, 46.4% of respondents believed that age did not mitigate psychopathic behaviour. Those who did think that antisocial personality disorder mellows with age variously suggested psychological, neurological and social factors as most influencing the process.

What do we know about older people in secure settings?

The criminal justice system

The ageing population is one explanation for the increasing number of older people coming into contact with the criminal justice system in Western countries (Reference Fazel, Gunn and TaylorFazel 2014). Prisoners may grow old in prison as more receive lengthy sentences, especially in the USA (Reference Lewis, Fields and RaineyLewis 2006); prisoners aged 50 and over account for 15% of the prison population and those aged 60 and over are the fastest growing age group in prisons (Prison Reform Trust 2016). In 2013, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales noted that ‘The number of older prisoners is rising rapidly and the prison service is becoming a major provider of care and accommodation of older people. It needs a much clearer strategy for meeting this growing need’ (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons 2013: p. 10), and added that the ‘specific needs [of older prisoners] may be overlooked in a system geared towards managing the much larger proportion of younger men’ (p. 37).

Historically, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) was less likely to take action against an older person accused of committing a crime, particularly if there was unclear intent, denial or mental illness (Reference Needham-Bennett, Parrott and MacDonaldNeedham-Bennett 1996; Reference Nnatu, Mahomed and ShahNnatu 2005). Reference Hunt, Nicola Swinson and FlynnHunt et al (2010) noted that, compared with those under the age of 65, those aged 65 and over more often received a verdict of manslaughter on grounds of diminished responsibility and a hospital order than a murder verdict. In a sample of older people referred for psychiatric evaluation in the USA, one-third were found unfit to stand trial and 10% were found not criminally responsible (Reference Lewis, Fields and RaineyLewis 2006). The police disproportionately dropping charges or choosing to caution older offenders may interfere with the true picture of antisocial behaviour (Reference Fazel, Gunn and TaylorFazel 2014). However, other recent sentencing data (Prison Reform Trust 2015, 2016) potentially indicates a less lenient and more proactive attitude to convicting and sentencing older people.

In a survey of 15 prisons in England and Wales, Reference Fazel, Hope and O'DonnellFazel et al (2004) found that the treatment needs of older prisoners were often not met. More recently, Age UK released guidelines on providing an appropriate environment and support for older people in prisons and also highlighted a number of good practices (Reference Le MesurierLe Mesurier 2011). Reference Kingston, Le Mesurier and YorstonKingston et al (2011) found that 50% of prisoners in England had a diagnosable mental disorder, with depression the most common, and that 12% had cognitive impairment (scored ≤26 on the Mini Mental State Examination). Physical health problems were also common, with an average self-report of 2.26 problems per prisoner. Kingston et al concluded that mental disorders in older prisoners are often ‘undetected and untreated’. Despite this, there is currently only one specialist older people's unit in the prison estate in England, at HMP Norwich, which provides an in-patient healthcare facility for older life-sentence prisoners. Some prisons provide separate accommodation for older prisoners: HMP Frankland, HMP Kingston and HMP Wymott (Reference Fazel, Gunn and TaylorFazel 2014). In US prisons, the provision of age-appropriate accommodation and services for older people is more advanced (Reference AdayAday 2003), recognising the growing population of older people serving long sentences, as well as older first-time offenders.

Fitness to plead and stand trial and mens rea

Clinicians involved with older offenders during the court process may need to consider the question of fitness to plead and stand trial. The ability to ‘follow the course of proceedings’ is particularly important in older offenders with cognitive impairment. Part of the associated assessment may involve assessing cognitive functioning, testing memory, attention, executive functioning and language skills. However, there are several other strands to this assessment, such as physical health and mobility, visual or hearing impairment, mental health, and social and psychological issues. Clinicians need to bear in mind that problems in these areas are likely to be common in older offenders. However, taking such factors into account through ‘special measures directions’ such as provision of communication aids or regular breaks can enable older offenders to participate in the court process.

There is no difference in how mens rea is considered in older offenders, although the factors (e.g. capacity) that impinge on it may be different.

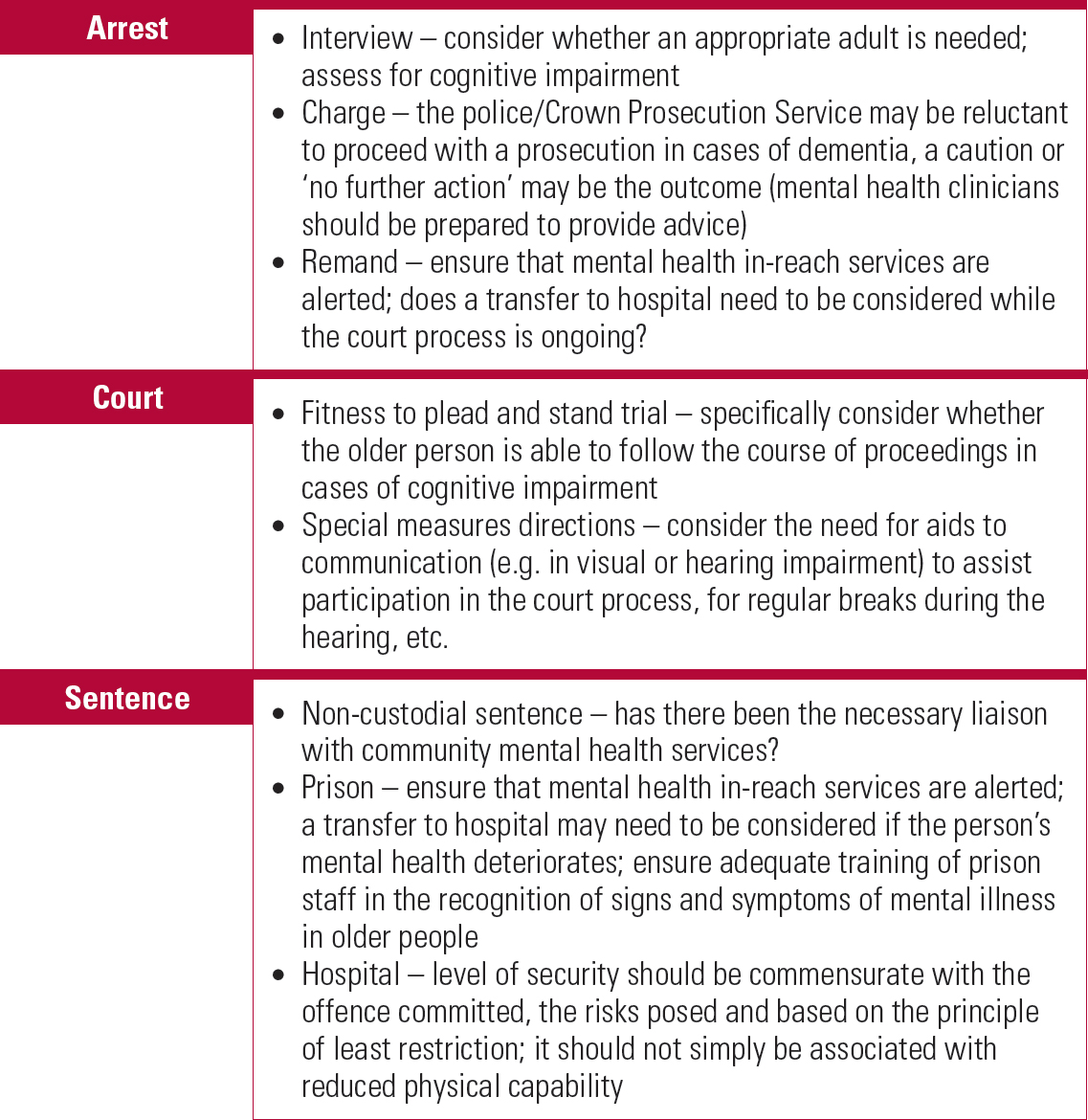

The journey through the criminal justice system for older mentally disordered offenders can be complex: Fig. 1 provides some good practice points at the different stages.

FIG 1 Good practice points for mental health clinicians when managing older people in the criminal justice system.

Mental health services

People aged 60 and over account for 8% of restricted patients detained in hospitals in England and Wales (Ministry of Justice 2010) and represent around 1% of referrals to forensic mental health services in the UK (Reference Tomar, Treasaden and ShahTomar 2005). Unfortunately, a lack of appropriate secure hospital beds has probably contributed to an inappropriate number of older mentally disordered offenders remaining in prisons. It has been recognised that some older patients in high secure hospitals could be suitably placed in less secure environments; however, there has been a long-standing gap in provision at lower levels of security. In the past decade a number of specialist secure in-patient psychiatric services for the assessment and management of older mentally disordered offenders have been established in the UK (Box 1). It is argued that many older people who have committed less serious offences could be managed safely in the community if the right expertise and services were available (Reference Yorston and TaylorYorston 2006). However, the provision of older people's forensic community psychiatric services remains much less developed than in-patient services.

BOX 1 Secure in-patient mental health services for older people in England

| Provider | Level of security |

|---|---|

| Partnerships in Care, Romford and Blackburn | Low (men) |

| St Andrew's, Northampton and Birmingham | Medium and low (men); low (women) |

| St Magnus Hospital, Haslemere | Low (men) |

| Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust, Middlesbrough | Low (men) |

| The Priory Thornford Park, Thatcham | Low (men) |

Why we need forensic mental health services for ‘older’ people

Commissioning specialised services

The Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health (JCPMH) is a collaboration between 17 leading UK organisations that is co-chaired by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of General Practitioners. Its guidance on commissioning public mental health services recognises the need for specialised services and states that they should be able to assess and manage the physical health, cognitive and psychosocial needs of older people alongside their mental health (JCPMH 2013a). In addition, its guidance for commissioners of forensic mental health services states that secure services ‘should meet the needs of “protected groups” as defined in the Equality Act 2010’ (JCPMH 2013b: p. 15).

Some older people may not want to be placed in an older people's service, seeing themselves as younger than their chronological years. Chronological age may not therefore be the defining characteristic for placement, and commissioning should be based on need (Department of Health 2009; JCPMH 2013c) and biological age.

A needs-based service may present its own problems, in that it may be more difficult to define and operate (Reference AndersonAnderson 2011). Reference Fazel, Hope and O'DonnellFazel et al (2004) noted that psychiatric needs were predominantly unmet in prisons, e.g. only 18% of prisoners with a recorded psychiatric problem were receiving psychotropic drugs. Reference LaidlawLaidlaw (2012) states that older prisoners with cognitive decline or dementia who do not meet the threshold for hospital-based treatment remain in prison, but their social care needs are often not met in the way that they would be were they still in the community. The question is whether the threshold for transfer to hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983 should take into account both the psychiatric and the social care needs of older prisoners.

Reference Fazel, Gunn and TaylorFazel (2014) notes that the admission of older people with dementia to younger people's secure mental health units would present problems, in that medical and allied healthcare staff would have little experience in the management of such patients.

Box 2 summarises the advantages and dis-advantages of forensic mental health services for older people.

BOX 2 Advantages and disadvantages of forensic mental health services for older people

Advantages

-

• Expertise and knowledge of older people's forensic mental healthcare

-

• Availability of expertise in physical healthcare and allied medical specialities

-

• Ability to consider the impact of physical health and cognitive difficulties on risk assessment and management

-

• Maximises knowledge of relational and procedural security as applicable to the management of risk in older people

-

• Age-appropriate and needs-based programme of therapies and activities, which can take into account cognitive difficulties or physical health problems

-

• Therapeutic milieu of an age-specific environment

-

• Reduction in social isolation

-

• Environmental adaptations

-

• Awareness of issues related to older offenders when liaising with other agencies, e.g. criminal justice system, Social Services

-

• Understanding and ensuring dignity and respect

-

• Reduced vulnerability from younger people

-

• Person-centred care and holistic approach

Disadvantages

-

• Services not always local to home area where family/relative/carer support is available; this may also make visits more difficult

-

• Older people may not want to be placed in an age-specific environment, seeing themselves as younger than their chronological years

-

• Potential support mechanisms provided by younger people are lost

The assessment and management of risk

Older people can be vulnerable in an in-patient setting that also accommodates younger people. On the other hand, a significant number of older people have committed serious sexual offences against children and/or young adults and may pose a risk to younger people. Therefore, age-appropriate placement is an important risk management strategy in mitigating risk of predatory sexual behaviour. In sexual offending, risk can be underestimated if based on age alone.

Reference KnightKnight (1983) found that spousal homicide committed by older people (what he called Darby and Joan syndrome) was characterised by the use of alcohol as a disinhibitor, extreme violence and subsequent completed or attempted suicide. Knight noted the absence of significant warning signs to the offence, although depression, marital difficulties, financial problems and/or recent contact with a medical practitioner were reported prior to these homicides. Reference Bourget, Gagne and WhitehurstBourget et al (2010) found that in 42% of the deaths of older women and 25% of older men by spousal homicide, the perpetrator was a caregiver to a chronically ill spouse.

Older people require the same levels of supervision and support from a risk management point of view as younger people, but it is argued that, for two reasons, the risks of this group are not always assessed accurately and are more difficult to judge. First, the standardised risk assessments routinely used in prisons and forensic mental healthcare, such as the Offender Assessment and Sentence Management system (OASys) and Historical Clinical Risk Management-20 (HCR-20), relied largely on younger people for their standardisation group, making them less useful when predicting the future behaviour of people no longer within that age group. Second, risk assessment may be biased by society's views of older people, with older offenders being viewed as less dangerous than younger offenders (Reference Nnatu, Mahomed and ShahNnatu 2005). Therefore, clinicians need to be aware that the risks older people present may be consciously or subconsciously minimised and should ensure that age-specific factors are considered when assessing risk of violence and of recidivism (Box 3).

BOX 3 Factors associated with risk of violent offences by older people

The following factors may be associated with an increased risk of violent offences by older people with mental disorder:

-

• paranoid symptoms (may be part of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, BPSD)

-

• delusional jealousy (othello syndrome; common in dementia)

-

• not receiving treatment for mental disorder at the time of an offence (men)

-

• victim characteristics – family, acquaintances and neighbours at most risk

-

• weapons that are easily available are often used, e.g. blunt objects such as a lamp, sharp objects such as a knife

Further, the prediction of risk is complicated in cognitive impairment, as risk may either increase or decrease as the impairment progresses. In older people with dementia, a change in behaviour may include new behaviours and changes in the type, frequency and characteristics of existing behaviours. In frontotemporal dementia, disinhibition and loss of empathy, insight and judgement are prominent factors associated with possible violence, and transgression of social norms may be interpreted as dissocial behaviour; a change in personality could affect the relevance of historical risk factors, leading to under- or overestimation of risk. Assessments and interventions for mental disorder and risk, including work on offending, can take longer to complete or may not be possible in older people because of factors associated with cognitive impairment and physical illness that make it difficult for them to engage meaningfully in this work.

Impact of ongoing mental illness

Many older offenders have moved on from general adult psychiatric services, having had a mental disorder such as schizophrenia for decades. They may have developed associated cognitive, occupational and functional impairments due to institutionalisation that can be better managed in an age-appropriate setting.

Impact of physical health problems

Older people with impairment in mobility may present less risk of violence to others, although this may increase the risk to themselves. Reference CattellCattell (2000) notes that older people, particularly older men, with mental disorder and comorbid physical conditions are at greater risk of dying by suicide.

The physical health needs of older offenders are considered to be greater than those of younger offenders in prison and older people in the community, with 83% experiencing a long-standing illness or disability (Reference Fazel, Hope and O'DonnellFazel 2001b). Research from the UK (Reference TarbuckTarbuck 2001) and USA (Reference Lemieux, Dyeson and CastiglioneLemieux 2002) that gathered information on the healthcare needs of older prisoners between 1977 and 2001 supports this, indicating that older people in prison experience higher rates of chronic diseases. Visual, hearing and mobility impairments are also common in prisons, with around 25% of a sample of older prisoners found to be experiencing a visual impairment and nearly 50% a hearing impairment (Reference Curtice, Parker and WismayerCurtice 2003). The physical health difficulties of older offenders are likely to increase their social isolation, often resulting in increased stress. Older prisoners with poor physical health might be at an increased risk of abuse, and might be unable to cope with the physical environment of their prison (Reference TarbuckTarbuck 2001). It is noted that older people in prisons do not always get the support that they require for their physical health needs, resulting in deterioration in their physical health (Reference Fazel, Hope and O'DonnellFazel 2004). The physical health of older prisoners is estimated to be equivalent to that of older people in the community who are up to 10 years their senior, and long-sentence prisoners grow old and frail in prison; prisons need to adjust to accommodate this increasing physical frailty. Services for older prisoners are often poor, there is a lack of staff training, inadequate provision of palliative care is a major concern and there are no appropriate age-specific assessments or arrangements. The principal objective should be to provide an ‘equivalence of care’ for prisoners compared with their peers in the community (Reference Fazel, Hope and O'DonnellFazel 2004). Although our discussion here is limited to older prisoners, this information likely reflects the physical health morbidity and physical healthcare needs of older people in forensic psychiatric in-patient settings.

Operating an older people's forensic mental health service

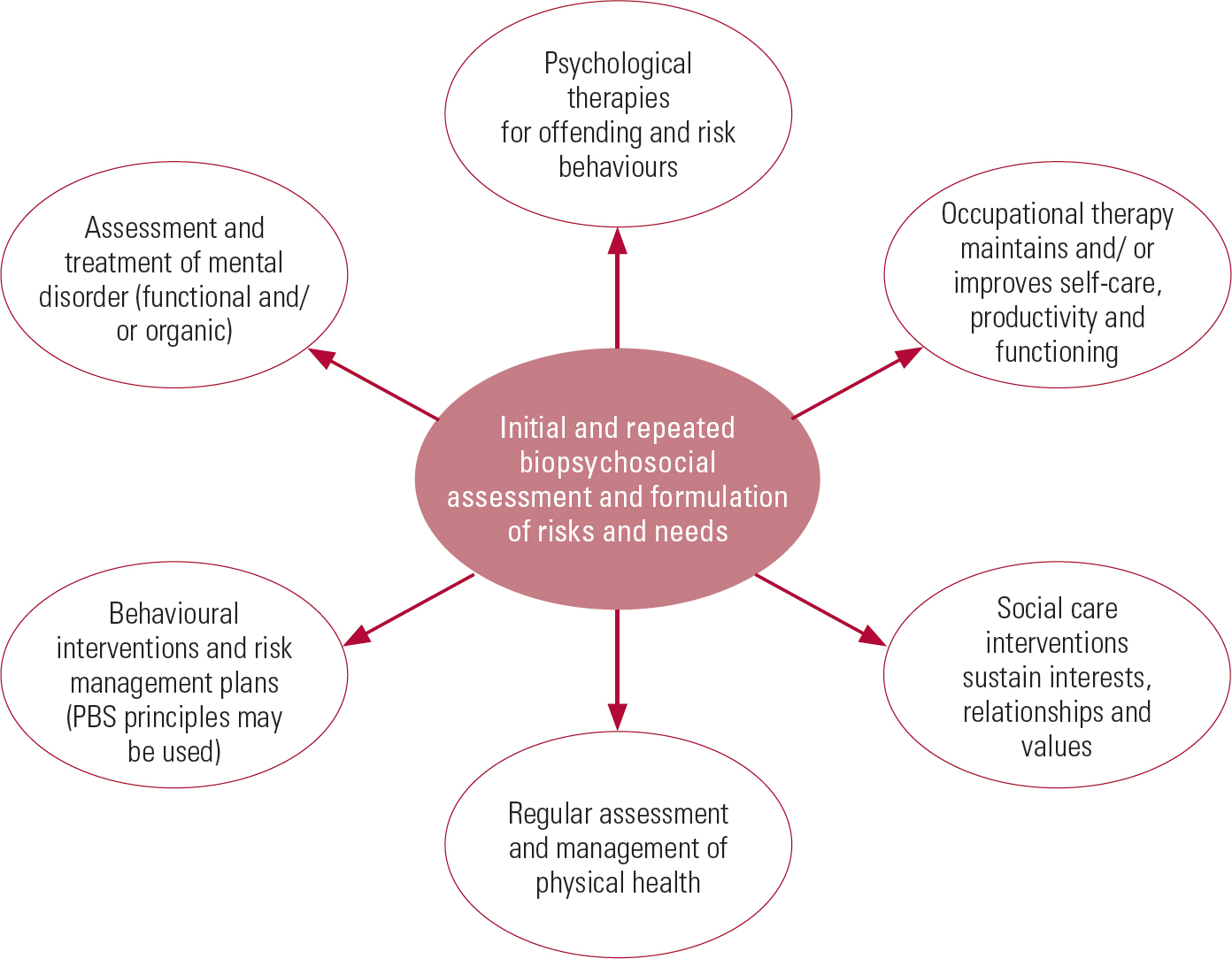

The difficulties in assessing risk and catering for the needs of older people in generic forensic mental health services and prisons suggests that age-appropriate services are best placed to provide care. It is likely that there will be an increasing need for expertise in identifying and managing risk presented by older people in the community, especially those who have committed their first offence when older. With this in mind, older people's forensic liaison may be a necessary part of future service models, capable and ready to advise old age and forensic services. Figure 2 outlines our suggested service operating model for this.

FIG 2 Service operating model for working with older offenders with mental disorder. PBS, positive behavioural support.

The model is governed by two overarching principles: reducing and managing risk and maximising quality of life. These will be achieved by working within a holistic multidisciplinary assessment and treatment pathway that caters specifically for the psychiatric, emotional, cognitive and physical needs of older people, taking into account risk to self and others, cohort beliefs, life stages, and life and role transitions. Individualised treatment plans can be developed using a biopsychosocial model to formulate an understanding of how these needs interact and contribute to the patient's distress and risk to self and others. Assessment and treatment can be categorised into three main phases:

-

1 stabilisation and containment, i.e. managing and reducing acute risks and distress while conducting assessments to guide treatment;

-

exploration and reducing risk, i.e. managing past and current problems that contribute to the patient's distress and offending behaviour;

-

relapse prevention and moving on, i.e. supporting the patient to consolidate skills they have acquired, in readiness for a move to a less secure or community environment.

For patients unable to engage in individual work to address these issues, the ‘exploration and reducing risk’ stage is often about developing positive behavioural support plans to achieve stable behaviour. Relapse prevention is then about ensuring that plans are robust enough to allow the individual to move to a less secure or community environment. Their physical health and/or cognitive difficulties may mean that progression through the stages of treatment is not achieved in a sequential order.

Staff expertise and training

Medical expertise in the management of both older people's mental illness and forensic mental illness should be available. To this end, specialty training programmes in psychiatry should offer specific experience in these two areas. Physical healthcare can be a significant part of the medical and nursing role; therefore, a number of nursing staff should be dually qualified in mental healthcare and general nursing. Where this is not possible we suggest that a few nurses develop specialist skills in physical healthcare and/or the assessment of cognitive functioning and management of dementia.

The expertise of a visiting geriatrician for the longitudinal management of chronic physical health conditions can provide valuable consistency. There should be effective secondary prevention strategies for those with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular problems; in vascular dementia, this can reduce the rate of decline in cognitive functioning (Reference Fillit, Nash and RundekFillit 2008).

The social work team should advocate for patient interests and values, liaise with relatives and carers, and assess capacity and best interests when needed. It should also take the lead on safeguarding and liaise with public protection and victim liaison agencies.

Occupational therapy can be provided using the framework of the Model of Human Occupation Screening Tool (MOHOST) or similar. All patients should undergo an initial assessment to gain an understanding of their interests, roles and values, as well as an impression of their level of functional ability. On the basis of these assessments, person-centred treatment programmes for self-care, productivity and leisure are developed and delivered, taking into account mental health, physical health and cognitive functioning. These interventions are delivered in collaboration with the multidisciplinary team and aimed at maintaining, restoring or improving the person's occupational functioning in order to maximise their independence. Risk management is an ongoing focus in occupational therapy.

Speech and language therapy for communication needs and dysphagia, dietetics for weight management and healthy eating, and physiotherapy for the management of mobility problems and assessment of the risk of falls, are all crucial in this service model.

Therapies

In terms of psychological treatment for mental disorders and offending behaviour, older patients should be able to access interventions available to the rest of the adult forensic population, including group therapies with younger people. This can reduce organisational constraints associated with service delivery and cost. Interventions include social problem-solving, dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) and sexual, violence and arson treatment programmes.

To cater specifically for the needs of older people, interventions may be needed that are not often standard in secure mental health in-patient settings. These include cognitive stimulation therapy (CST), life-story and reminiscence work and adapted offence-focused work for those with a mild to moderate dementia. A number of these specialist treatments are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2006 Health and Care Excellence (2015). There should be expertise in behavioural interventions for those who present with complex clinical and risk paradigms that are not amenable to individual or group treatments. Compensatory strategies such as orientation aids may be needed to help individuals with dementia and other cognitive difficulties. On an in-patient ward, regular or daily planning meetings would help orient patients and facilitate structuring of their day.

Differing levels of cognitive and physical ability can affect what treatments and activities are appropriate, so these should be offered within two broad streams, for those who are more functionally able and for those who have more advanced difficulties in cognitive functioning. The latter group can display unique and complex presentations due to multiple impairments and it is essential that the service operating model incorporates these needs.

Adaptations to the in-patient environment

Seclusion and low-stimulus rooms should contain a specialist chair and mattress to allow those with mobility problems to be comfortable and safe. Personal care equipment and facilities should be adapted for individual needs: shower chairs, grab rails, raised toilets, higher beds, wheelchairs and walking aids may be required. The therapy (rehabilitation) kitchen should be adapted for those with mobility and coordination difficulties. These adaptations are not considered in standards for low or medium secure units and will therefore require careful risk assessment and management.

Setting up and operating an older people's secure mental health in-patient unit

The following information is from our own experience of setting up an in-patient secure mental health unit for older people.

A high proportion of our older patients have comorbid physical health problems, in some cases presenting with multiple acute and chronic conditions such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, recurrent infections, and the complications of dementia seen in the natural history of the disease. There is consequently a high level of behavioural disturbance on the ward, requiring a high staffing ratio. Nevertheless, there can still be an ‘expertise gap’, as patients may also have intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder and/or personality disorder. Addressing this problem is dependent on the delivery of suitable training and professional development activities for staff.

The unit admits younger patients with early-onset dementia or physical or mobility impairments deemed to need the expertise and environmental adaptations of an older people's service if the associated risks can be managed.

There are ongoing service development needs, particularly further adaptations to improve the environment's suitability for older people. The continued development of staff expertise in matters relevant to older mentally disordered offenders is of key importance. These include knowledge of the interaction between mental and physical illness, adequate risk management while maximising quality of life and the maintaining of a safe environment for a vulnerable patient group.

Table 3 shows the clinical and offending characteristics of 25 referrals to an older men's medium secure mental health unit over an 18-month period.

TABLE 3 Clinical and offending characteristics of 25 referrals to a medium secure older men's unit in the UKa

The cost per bed-day for psychiatric care is about £500, which is the same as the cost per bed-day for an adult forensic bed, however there are additional costs primarily associated with the extra resources needed to manage physical healthcare, i.e. staff (including escorts for general hospital appointments or admission), equipment and expertise. The importance of experience and expertise cannot be understated, and is a key determining factor in whether such services should develop within the forensic estate. Increasing ‘super-specialisation’, which has seen the development of specialist forensic service provision for autism, intellectual disability and neuropsychiatry, arguably does offer improved patient experience and outcomes and would allow a greater focus on the needs of older people (Reference Ginn and RobinsonGinn 2012). The fictitious case vignettes in Boxes 4 and 5 exemplify the complex needs of older mentally disordered offenders and demonstrate why specialist services are an invaluable resource.

BOX 4 Illness-appropriate risk management

A.B. is aged 65 and has Alzheimer's disease of mild severity. He has no significant mobility problems. He is alleged to have committed a series of contact sexual offences against children and is currently on remand in prison for these offences. He is disoriented and neglecting himself; staff at the prison feel he is in the wrong place. He is subsequently found unfit to plead to the charges, but is found to have committed the acts. He receives a hospital order with restrictions (under section 37/41 of the Mental Health Act 1983) and is admitted to a secure older men's mental health unit. In hospital his cognitive functioning declines over a period of 2 years. He is unable to engage in offence-related work and consequently his risks cannot be demonstrated to have reduced. He does participate in therapies such as cognitive stimulation and reminiscence. A longitudinal assessment of his behaviour finds little evidence of offence-paralleling behaviours and indicates that his risks can be managed in a risk-managed environment. On the basis of this evidence, a positive risk-taking approach is planned and delivered. After successful escorted leave into the community, he moves to a less secure placement closer to his family.

BOX 5 Safeguarding and age-appropriate placement

C.D. is aged 61 and has treatment-resistant schizophrenia with ongoing psychotic symptoms. He has been referred from an adult secure unit where he had spent the past 10 years. He had been vulnerable on the adult ward, with a number of instances of retaliatory assaults by fellow patients who were much younger than him. There are a number of ongoing safeguarding concerns. Following his admission to an older men's secure unit it is noted that he is more settled. The age-appropriate environment and activities provided enable him to spend more time interacting and he develops appropriate friendships with some patients. The staff are able to work with him on a behaviour management plan and identify environmental triggers that result in an increase in his psychotic symptoms or behavioural difficulties. He says that he feels more comfortable and safe where he is now.

Conclusions

Older people who require forensic mental healthcare have complex needs (cognitive, physical and psychosocial) that are different from the needs of younger people. Further research is needed on older mentally disordered offenders currently managed in younger people's forensic mental health services and in prisons, whose needs may not be being appropriately met. Reference Tomar, Treasaden and ShahTomar et al (2005) ask whether there is a case for specialist forensic psychiatry services for older people – we firmly say yes. However, it is debatable whether there is a need to commission secure in-patient services for older people regionally or whether supraregional (Reference Tomar, Treasaden and ShahTomar 2005) catchments may be more economical and strategically viable. A piecemeal approach to service planning and development should be avoided and the specialist needs of this population must not be overlooked.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The percentage of older prisoners who have a mental disorder is in the range:

-

a 25–30%

-

b 1–3%

-

c 50–54%

-

d 80–90%

-

e 58–62%.

-

-

2 The most common type of offending behaviour in men over 59 in prisons in the UK is:

-

a violence

-

b sexual offending

-

c drugs

-

d arson

-

e fraud.

-

-

3 Factors that can affect the ability of an older mentally disordered offender to engage meaningfully in work to reduce their risks include:

-

a cognitive impairment

-

b physical health

-

c psychosocial issues

-

d psychotic or affective symptoms

-

e all of the above.

-

-

4 The lower prevalence of dementia in prisons than in the community might be explained by:

-

a diversion to hospital or transfer from prison

-

b those with dementia being unable to commit an offence that would result in imprisonment

-

c a lower case progression and conviction rate

-

d poor identification rates of dementia in prison

-

e all of the above.

-

-

5 As regards forensic mental health services for older people:

-

a they should be based on an age-specific cut-off

-

b specialist or adapted treatments to meet the needs of cognitively impaired patients should be available

-

c older people should not be placed in a level of security commensurate with their offence or risks

-

d community forensic mental health services for older people are well developed in the UK

-

e risk assessments specific to older people are in routine use.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | b | 3 | e | 4 | e | 5 | b |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.