LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• better understand the relationship between religion and mental health

• demonstrate up-to-date knowledge of the evidence for a relationship between religiosity and mental health, both on how religiosity affects mental health and how mental health affects religiosity

• demonstrate awareness of how research on the relationship between religiosity and mental health informs clinical practice today.

During most of the 20th century, religion was considered a source of neurosis, a negative influence on mental health. Such attitudes towards religion were based largely on the opinions of influential mental health professionals, not on objective systematic observation of those with and without mental illness (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). In the last decade of the 20th century and first two decades of the 21st, the findings from quantitative research tell a different story. The purpose of this article is to review research published in the past 10 years that has examined the relationship between religion and mental health. We also briefly summarise research published before 2010, as documented in the Handbook of Religion and Health (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012), which presents a systematic review of the literature up to that date. The more recent research described in this article, however, is presented not as a systematic review, but rather as a summary that selectively highlights the best available studies, in our opinion, chosen on the basis of their methodological rigor.

Definitions

We define ‘religion’ here as beliefs, practices and rituals related to the ‘transcendent’, where the transcendent is often God in Western religious traditions or, in Eastern traditions, is considered to be ultimate truth, reality or enlightenment. Religion may involve beliefs about spirits, angels or demons, and often entails specific beliefs about life after death and rules to guide behaviour during the present life. Religion is often organised and practised within a community, although it can also be practised alone and in private. Central to its definition is that religion is rooted in an established tradition that arises out of a group of people with common beliefs and practices concerning the transcendent. Religion is a unique construct, although there are still debates over the exact nuances of the definition (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). Religiosity, in turn, is the extent to which religious beliefs and practices are important in a person's life. Since the focus in this article is on research, we do not use the broader term ‘spirituality.’ The reason is because there is little agreement on the definition of spirituality and there are serious questions about tautology in its measurement that influence relationships with mental health (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). However, when spirituality is measured by religious involvement or by concepts related to the transcendent more broadly (but not contaminated by indicators of mental health), we refer to religion/spirituality together.

Negative mental health

In discussing the relationship between religiosity and the negative side of mental health, i.e. mental disorder, we review the latest research on depression, bipolar disorder, suicide, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorder, personality disorder and chronic psychoses. Given the limited space, we try to avoid cross-sectional studies, but rather focus on longitudinal prospective cohort studies where available. Such studies contribute evidence not only to correlation but have the potential to contribute evidence for causation (VanderWeele Reference Strawbridge, Shema and Cohen2016a).

Depression

A systematic review of quantitative research up to 2010 (both observational and experimental work) reported that 444 studies had examined the relationship between religion/spirituality and depression (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). Of those studies, 272 (61%) reported that religious involvement was associated with less depression or faster recovery from depression, or that religious interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms. Several additional prospective studies on this relationship have been published since 2010. For example, in a sample of individuals at high risk for major depressive disorder a magnetic resonance imaging study compared brain structure of those who said that religion/spirituality was ‘very important’ in their lives with that of those who said it was only ‘somewhat’ or ‘not at all’ important (Miller Reference Li, Okereke and Chang2014). Researchers found that the reduced cortical thickness characteristic of those at high risk for major depressive disorder was substantially less among those who said that religion/spirituality was very important, compared with those who indicated otherwise. Similar findings were reported for frequency of religious attendance, although these effects were reduced to non-significance when controlling for the importance of religion/spirituality.

The causal direction of the relationship between religious attendance and depression has been debated because depression may also affect religious attendance, thus potentially explaining some of the inverse correlations frequently reported. In an analysis of data on nearly 50 000 female nurses from the Nurses' Health Study, a very large prospective study in the USA, Li et al (Reference Koenig, Youssef and Ames2016) found that although recent depression predicted a 26% subsequent decrease in religious attendance, religious attendance also predicted a 29% subsequent reduction in depressive symptoms during the 12-year follow-up. Thus, religious attendance and depression likely have bidirectional effects on each other, at least in women; bidirectional effects have not yet been shown for other indicators of religiosity or for men. Although prospective studies finding protective effects of religion on depressive symptoms are primarily from the USA, recent studies in Europe have demonstrated similar findings (e.g. Croezen Reference Chen and VanderWeele2015; Lorenz Reference Koszycki, Bilodeau and Raab-Mayo2019).

Bipolar disorder

Compared with research on depression, relatively few studies have examined religiosity and bipolar disorder. Well-known are the grandiose symptoms of hyper-religiosity during mania. However, does religious involvement during periods of remission help to prevent depressive or manic episodes, thereby helping to stabilise the disorder? Although several cross-sectional studies have examined this relationship, reporting no association, fewer episodes and more episodes, we are aware of only one prospective study. Stroppa et al (Reference Stroppa, Colugnati and Koenig2018) followed 158 Brazilian out-patients with bipolar disorder from 2011 (baseline) to 2013 (follow-up), examining the effect of baseline religiosity and religious coping (positive and negative) on symptoms of mania, depression and quality of life (QOL) at follow-up. Positive religious coping and religiosity were both associated with lower depression scores at baseline. Positive religious coping also predicted significantly better quality of life (physical, mental, social, environmental) at follow-up, whereas religiosity significantly predicted only better environmental QOL at follow-up. Negative religious coping (religious struggles), in contrast, predicted more manic symptoms and lower QOL at follow-up.

Suicide

Up to 2010, 141 studies had examined the relationship between religiosity and suicide (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). Of those, 106 (75%) reported that religious involvement was inversely related to suicidal thoughts, attempts or completions. Since 2010, several large prospective studies have confirmed these findings, reporting that religious involvement (particularly religious attendance) predicts a lower suicide risk. For example, Kleiman et al (Reference Kelly, Bergman and Hoeppner2014) examined whether frequency of religious attendance (assessed at any time between 1988 and 1994) was associated with death by suicide by 2006 in a national random sample of 20 014 US adults. Cox proportional hazards regression models indicated that those attending religious services at least twice a month were 94% less likely to die by suicide than those attending less frequently (HR = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.01–0.54).

Likewise, in a 14-year follow-up of 89 708 women in the Nurses' Health Study, VanderWeele et al (Reference Stroppa, Colugnati and Koenig2016b) found that frequent religious attendance in 1996 predicted a lower risk of completed suicide by 2010, independent of multiple risk factors (HR = 0.16, 95% CI = 0.06–0.46), with more than a fivefold reduction in suicide incidence, from 7 per 100 000 to 1 per 100 000 person-years. The results, if extrapolated to the entire US population, would indicate that approximately 40% of the increase in the US suicide rate between 1999 and 2014 could be attributed to the decline in weekly religious attendance during that period (VanderWeele Reference Thygesen, Dalton and Johansen2017). Religious involvement likely reduces suicide risk by religious prohibitions against suicide and positive effects on suicide risk factors (e.g. alcohol/drug use, depression, isolation, loss of hope) (Koenig Reference Koenig, Pearce and Nelson2016).

Anxiety

Up to 2010, 299 quantitative studies had examined the relationship between religiosity and anxiety (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). Of those, 147 (49%) reported less anxiety among those who were more religious, whereas 33 (11%) found greater anxiety. There were also 41 experimental studies or randomised controlled trials (RCTs), of which 29 (71%) reported significantly lower anxiety among those receiving religious/spiritual interventions compared with control conditions. Just as reverse causation influences the relationship between religious involvement and depression, so it may influence the relationship with anxiety. However, in this case, unlike depression reducing religious activity, anxiety has the opposite effect, serving as a powerful motivator of religious practices. Those who are anxious often turn to religion for comfort and peace. This dynamic is reflected in recent prospective studies, which have reported mixed findings.

For example, Rasic et al (Reference Oman and Bormann2011) examined the effects of baseline religious attendance on anxiety disorder diagnosed 10 years later in 1091 community-dwelling adults from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. After controlling for demographics, social interactions, health conditions and baseline anxiety disorder, no effect was found for baseline attendance on anxiety disorder at 10-year follow-up. Besides having no effect, religiosity may also increase risk of anxiety over time, as Peterman et al (Reference Peterman, LaBelle and Steinberg2014) reported. That study followed 839 adolescents over a 3- to 4-year period from ages 11–12 (baseline) to mid-adolescence (follow-up at average age 15). An increase in religious attendance between baseline and follow-up was associated with greater anxiety symptoms at follow-up, controlling for gender, ethnicity, religious affiliation and baseline anxiety; conversely, those who indicated consistently low religious attendance at baseline and follow-up showed a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms at follow-up.

In contrast, several other large prospective studies have recently reported protective associations of religiosity on anxiety symptoms. For example, in a random US national sample of 1024 community-dwelling adults age 65 or older, Bradshaw et al (2014) asked participants how often they listened to religious music outside of church. Death anxiety was assessed at baseline and 3 years later (follow-up). After controlling for multiple sociodemographic, financial and health risk factors, including baseline death anxiety, listening to religious music at baseline predicted a significant decrease in death anxiety at follow-up, as well as significant increases in life satisfaction, self-esteem and sense of control. Likewise, in a prospective study of 47 psychiatric patients with current or past psychotic disorders admitted to a day treatment programme at Harvard Medical School's McLean Hospital, Rosmarin et al (Reference Raguram, Venkateswaran and Ramakrishna2013) examined the effect of religious coping (assessed on admission) as a predictor of change in anxiety and other psychiatric symptoms from admission to discharge (an average of 8 days). Investigators found that baseline positive religious coping predicted a significant decline in anxiety symptoms (r = 0.60, p≤0.001), whereas negative religious coping was unrelated to change in anxiety.

In light of the evidence, it is thus likely that religious participation relieves anxiety in some individuals and causes it in others. Further study of these dynamics merits attention. With regard to actual interventions, several recent RCTs involving religious interventions to treat anxiety in a variety of countries have consistently reported beneficial effects (Rosmarin Reference Pearce, Haines and Wade2010; Koszycki Reference Koenig, Ames and Pearce2014).

Post-traumatic stress disorder

As with research on anxiety disorders, prospective studies examining the effects of religiosity on PTSD report mixed findings, ranging from no effect on symptoms to either worsening or improving. An observational cohort study following 111 older male US military veterans with cancer over 6 months found that increases in religiosity predicted an increase in PTSD symptoms (Reference Steenhuis, Bartels-Velthuis and JennerTrevino 2016). In contrast, a study of 532 US veterans involved in a 60- to 90-day residential treatment programme for combat-related PTSD found that religion/spirituality assessed on admission (baseline) predicted significantly fewer PTSD symptoms at discharge, independent of baseline PTSD severity (Currier Reference Croezen, Avendano and Burdorf2015). Importantly, cross-lagged analyses revealed that the effect of baseline religion/spirituality on PTSD symptoms at discharge was stronger than the effect of baseline PTSD on discharge religion/spirituality, suggesting that the effect of religion/spirituality on PTSD symptoms was stronger than the effect of PTSD on religion/spirituality over time, providing evidence for causal inference.

Chen & VanderWeele (Reference Captari, Hook and Hoyt2018) followed a large cohort of adolescents (sample sizes varied from 5681 to 7458, depending on outcome) from an average age of 14.7 years at baseline over a period of 8–14 years. The effects of baseline religious attendance and prayer/meditation on PTSD symptoms at follow-up were examined. Controlling for multiple risk factors, baseline religious attendance (weekly or more versus never) predicted a nearly 30% lower likelihood of probable PTSD at follow-up (RR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.57–0.93). Likewise, baseline praying/meditating less than once weekly (versus never praying/meditating) also predicted a lower likelihood of probable PTSD at follow-up (RR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.53–0.97). As with anxiety disorders more generally, complex dynamics involving bidirectional effects make conclusions difficult. Relevant, though, are results from at least two RCTs reporting a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms with religious/spiritual interventions (Oman Reference Miller, Bansal and Wickramaratne2015; Harris Reference Good, Hamza and Willoughby2018).

Substance use disorders

Although recent findings for anxiety and trauma-related disorders are inconsistent, the evidence from prospective studies on the effects of religiosity on alcohol and drug use are not. In our systematic review (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012), 240 of 278 studies (86%) published before 2010 reported an inverse relationship between religiosity and alcohol use/misuse/dependence, and 155 of 185 studies (84%) reported similar findings for drug use/misuse/dependence. Researchers have only recently acknowledged the success of 12-step programmes (8 of the 12 steps of the Alcoholics Anonymous programme being religious/spiritual in nature; Box 1) given the mounting evidence (Kelly Reference Jung2017).

BOX 1 The Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous

1. We admitted we were powerless over alcohol–that our lives had become unmanageable.

2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

4. Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

5. Admitted to God, ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

6. Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

7. Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

8. Made a list of persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

9. Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

10. Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

11. Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

12. Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

(Alcoholics Anonymous 2001: pp. 59–60)

The Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous are reprinted with permission of A.A. World Services, Inc. (“A.A.W.S.”) Permission to reprint the Twelve Steps does not mean that A.A.W.S. has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication, or that A.A. necessarily agrees with the views expressed herein. A.A. is a program of recovery from alcoholism only - use of the Twelve Steps in connection with programs and activities which are patterned after A.A., but which address other problems, or in any other non-A.A. context, does not imply otherwise.

Since 2010, there have been at least 20 prospective studies examining the effects of baseline religiosity on alcohol use/misuse/dependence in samples ranging in size from 118 to 7458, many conducted in adolescents and young adults. Of those, 16 (80%) reported a positive effect of baseline religious involvement on alcohol outcomes (data available from the author on request). In 12 prospective studies examining drug use/misuse/dependence, all 12 (100%) found a positive effect of religiosity on drug use outcomes over time.

Personality disorder

Early studies published before 2010, most of them cross-sectional, reported that religious involvement was inconsistently related to DSM Cluster A paranoid and schizotypal personality disorders; inversely related to Cluster B borderline, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders in about half of studies; consistently related to less Cluster B antisocial personality disorder; and unrelated or often positively related to Cluster C obsessive–compulsive personality disorder and scrupulosity (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). Concerning ‘normal’ personality traits, religiosity was inversely related to psychoticism (risk-taking, lack of responsibility) in most studies; unrelated or inversely related to neuroticism; unrelated or positively related to extraversion; unrelated or positively related to openness; and consistently and positively related to conscientiousness and agreeableness.

Since 2010 there have been a few prospective studies on the relationship between religion/spirituality and personality disorder. Good et al (Reference Currier, Holland and Drescher2017) analysed data from a 1-year prospective study of 1132 first-year Canadian college students, examining the effects of religion/spirituality on non-suicidal self-injury (including ‘cutting’ behaviours, a common practice in borderline personality disorder). Religious questioning/doubting and organisational and non-organisational religious activities were assessed at baseline and 12-month follow-up. After controlling for multiple risk factors, analysis revealed that baseline religious questioning/doubting positively predicted self-injury scores at follow-up, and baseline self-injury scores positively predicted religious questioning/doubting at follow-up. However, no effect was seen for organisational or non-organisational religious activities on self-injury. Several recent cross-sectional studies, however, have reported a positive relationship between religiosity and magical thinking (an aspect of Cluster A personality disorders).

A prospective study in 375 young Protestant Christians in Hong Kong found that becoming a non-believer (apostate) during a 3-year follow-up was unrelated to baseline neuroticism, extroversion, conscientiousness or agreeableness (Hui Reference Harris, Usset and Voecks2018). However, at least one experimental study in college students has found that religiosity predicts greater self-control and reduced impulsiveness (Rounding Reference Rasic, Robinson and Bolton2012). Recent cross-sectional studies have also found religiosity to be consistently related to less hostility, aggressiveness and anger (data available from the author on request).

Chronic psychotic disorder

Very little research has examined the relationship between religiosity and chronic psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. In an early research report, Raguram et al (Reference Ofori-Atta, Attafuah and Jack2002) described the effects of staying at a Hindu healing temple in South India on psychotic symptoms. Researchers examined 31 consecutive individuals with psychosis who came to stay at the temple (23 with paranoid schizophrenia, 6 with delusional disorders, 2 with psychotic mania). The severity of symptoms on the first and last day of their stay was assessed using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). No participants received any formal treatment during their stay. After an average 6-week stay at the temple, BPRS scores decreased by nearly 20%. Interviews with family caregivers indicated that 22 individuals had improved and 3 had recovered. The authors stated that this level of improvement rivalled that from antipsychotic drugs, including newer atypical agents.

More recent research is less encouraging. In the Rosmarin et al (Reference Raguram, Venkateswaran and Ramakrishna2013) study mentioned above, involving 47 psychiatric patients with current or past psychotic disorders attending a hospital day-treatment programme, religiosity on programme entry was unrelated to change in psychotic symptoms from entry to completion 8 days later. Likewise, in a prospective study in The Netherlands of 337 healthy children between 7 and 8 years of age with and without hallucinations, Steenhuis et al (Reference Semplonius, Good and Willoughby2016) found no effect of religiosity on course of symptoms during the 5-year follow-up. However, in a 39-year prospective study of 9277 community-dwelling Seventh Day Adventists and Baptists (conservative Christian faith traditions) in Denmark, the Seventh Day Adventists were less likely to be admitted to hospital for psychotic disorder during follow-up compared with the general Danish population (Thygesen Reference Spilman, Neppl and Donnellan2013).

In the only RCT on the subject, to our knowledge, Ofori-Atta et al (Reference Lorenz, Doherty and Casey2018) randomised 139 adults with serious behavioural disturbances (80% with schizophrenia) resident in a faith-based healing centre in Ghana to either a prayer camp plus medication intervention or prayer camp only (control group). Prayer camp activities for both groups involved a combination of prayer, Bible study and fasting, with chain restraints as necessary to control agitation. Those in the control group were treated with medication if urgently needed. Outcomes at 6 weeks were assessed using the BPRS. Results indicated significantly lower BPRS scores in the medication group compared with ‘prayer camp only’ controls (Cohen's d = 0.48, i.e., moderate effect). Among those with schizophrenia, effect size was even greater (d = 0.87, i.e., large effect). Long-term differences between groups beyond 6 weeks were not examined.

Summary

Thus, religiosity appears to be most effective in preventing suicide and substance use disorders; moderately effective in preventing depression, and possibly also trauma-related disorders and antisocial personality disorder and traits; but the findings are mixed for other personality disorders, anxiety, bipolar disorder and chronic psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia.

Positive mental health

In this section, we review the possible impact of religiosity on indicators of mental health resiliency, which may help prevent the onset of mental disorder or ameliorate its course. In discussing positive aspects of mental health, we focus on the impact of religiosity on marital/family stability, social support and psychological well-being.

Marital/family stability

Multiple studies have found that marital and family stability strongly predict mental health and well-being in marriage partners and children. Our systematic review up to 2010 identified 79 quantitative studies; of those, 68 (86%) reported greater marital or family stability in the more religious (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). There has been much further research since 2010, including several prospective studies. One of the largest of these analysed data on a sample of 66 444 married female nurses from the US Nurses’ Health Study followed from 1996 to 2010, examining impact of religious attendance in 1996 on likelihood of divorce over the 14-year follow-up (Li Reference Li, Kubzansky and VanderWeele2018). Cox proportional hazards regression examined time to divorce or censoring, controlling for many covariates. Nurses attending religious services more than once a week in 1996 were 42% less likely to divorce (HR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.44–0.74) and were 47% less likely to either divorce or separate (HR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.42–0.67) compared with non-attendees. Of the ten prospective studies identified in our most recent review (data available from the author on request), eight reported that greater religiosity predicted either less divorce or fewer divorce risk factors.

Concerning family stability, Spilman et al (Reference Rounding, Lee and Jacobson2013) used data from the Family Transitions Project (a 20-year longitudinal study of families in the USA) to examine the intergenerational transmission of positive interparental relationships and positive parenting. In a sample of 451 adolescents in two-parent families, where both the adolescents and their parents had been interviewed at multiple time points, they found that greater parental religiosity in 1991 was associated with greater adolescent religiosity in 1991–1994, which in turn predicted greater adolescent religiosity during young adulthood (average age 23 in 1997). Parental religiosity in 1991 was also associated with positive marital interactions in 1991–1994, which was positively associated with positive parenting in 1991–1994. Positive parenting and adolescent religiosity in 1991, in turn, predicted both positive young adult romantic relationships and positive young adult parenting in 1995–2007. The investigators concluded that religiosity was positively correlated with the quality of family relationships, which was transmitted across generations.

Social support

Social support, along with marital/family stability, is one of the strongest social determinants of mental health. In our earlier review, 74 quantitative studies were identified, of which 61 (82%) reported significant positive associations between religiosity and greater social support (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). Seven of those 74 studies were prospective, with five (71%) reporting positive relationships with religiosity and two finding no association. For example, in a 28-year prospective study of 2676 community-dwelling adults followed from 1965 to 1994, Strawbridge et al (Reference Shaheen Al-Ahwal, Al-Zaben and Sehlo2001) found that frequent religious attendance predicted a 62% increase in social relationships among those with few relationships in 1965.

Since 2010, at least one prospective study has examined the effects of religiosity on social support over time. Semplonius et al (Reference Rosmarin, Pargament and Pirutinsky2015) followed 1132 college students in Ontario, Canada, over a 3-year period, finding that greater baseline involvement in religious activities predicted less difficulty with emotion regulation over time, controlling for baseline emotion regulation; emotion regulation, in turn, predicted more social ties over time, controlling for previous social ties. Indirect effects indicated that religiosity significantly predicted an increase in social ties over time through improved emotion regulation.

Psychological well-being

Our earlier systematic review identified 326 studies published before 2010, of which 256 (79%) reported greater life satisfaction, happiness or other indicators of well-being among the more religious (Koenig Reference Kleiman and Liu2012). Most of these were cross-sectional, although nine were high-quality prospective studies, of which seven reported a significant positive relationship with religiosity. More recently, several high-quality prospective studies have confirmed these earlier relationships. For example, analysing data on 1635 American adults randomly selected from a national survey that followed a much larger cohort for 10 years, Jung (Reference Hui, Cheung and Lam2018) found that religiosity moderated the effect of childhood adversity on positive affect. Among those with low religiosity, childhood abuse significantly decreased adult positive emotions, whereas among those with high religiosity, no adverse effect of child abuse on mood was found.

Similarly, in the Chen & VanderWeele (Reference Captari, Hook and Hoyt2018) study described above, young persons who attended religious services at least weekly (versus never attending) experienced greater life satisfaction, more positive affect and developed more character strengths during follow-up.

Summary

In general, recent research confirms the positive impact that religious involvement has during youth and adulthood on marital and family stability, social support and psychological well-being, factors known to influence mental health resiliency.

Moral injury

Moral injury is a relatively new syndrome identified among military personnel with PTSD. If not recognised and addressed, moral injury may interfere with the effective treatment of PTSD. Although this syndrome has received considerable attention in the psychological sciences, it has received relatively little notice in the field of psychiatry until recently (Koenig Reference Koenig, Ames and Youssef2019a). Moral injury has been defined as the negative emotions that emerge following transgression of moral boundaries during combat operations (killing or mutilating enemy combatants or innocent civilians); failing to protect innocents or fellow combatants from harm; or observing others behave in this manner. Symptoms characteristic of moral injury include guilt, shame, feelings of betrayal, self-condemnation, loss of trust, loss of meaning and purpose, difficulty forgiving, religious struggles and weakening or loss of religious faith. Although there is some overlap between symptoms of moral injury and those of PTSD (particularly DSM Criterion D negative emotions), these are two distinct conditions each with unique characteristics (Koenig Reference Koenig, Youssef and Pearce2020).

Moral injury may also occur in settings outside the military following severe trauma, such as sexual assault, natural disasters or serious accidents. Moral injury may even occur in the absence of severe trauma, particularly when individuals violate moral standards. This includes medical settings, if health professionals are forced into situations where they compromise their moral and ethical beliefs and this results in patient harm or death. Morally injurious experiences of this type may be an unrecognised contribution to clinician burnout, a condition that today has reached epidemic proportions. Moral injury is far from a benign syndrome, given its robust associations with PTSD, depression, anxiety and risk of suicide (Koenig Reference Koenig, Ames and Youssef2019a).

Several brief psychometrically valid measures have been developed to screen for moral injury among military personnel. A 10-item scale to assess symptom severity and treatment response in military personnel (Koenig Reference Koenig2018a) is now being adapted for civilians and healthcare professionals (Koenig Reference Koenig2019b: pp. 308–314). This scale is unique in assessing both the psychological and the religious/spiritual symptoms of moral injury. Religiously integrated interventions for moral injury are also now being tested in RCTs (Pearce Reference Pearce, Haines and Wade2018; Harris Reference Good, Hamza and Willoughby2018).

Theoretical causal pathways

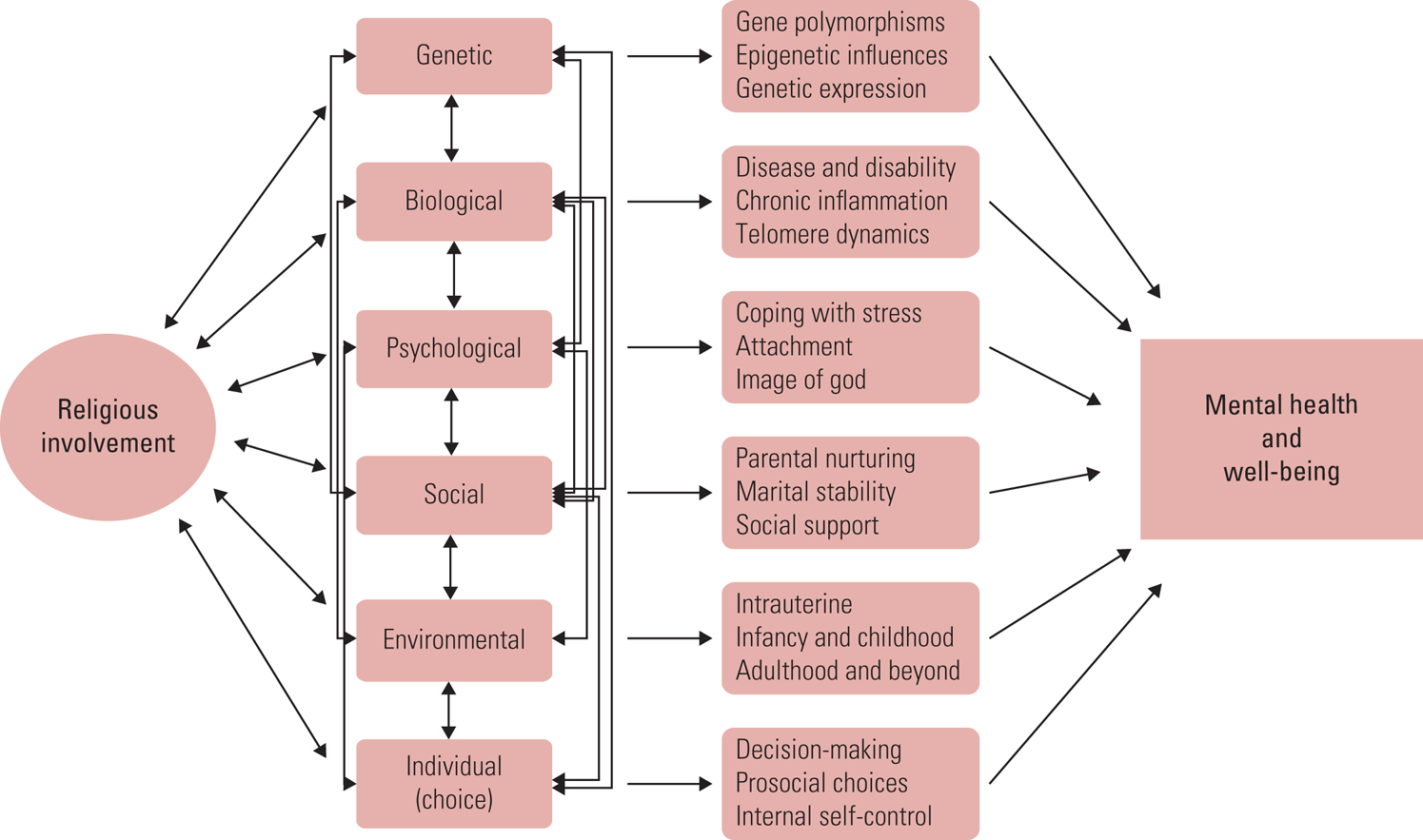

Religious involvement is thought to prevent the development of mental disorder (or ameliorate its course) and increase mental health resiliency through several pathways, beginning before birth and extending across the lifespan (Fig. 1). Those pathways include genetic, biological, psychological, social, environmental and individual-level (behavioural) mechanisms. Genetic factors may reduce religious individuals' likelihood of experiencing mental disorder, as research has shown for substance use disorders (for citations see Koenig Reference Koenig2018b). Biological factors involve religion's effect on development of physical illness, disability and chronic inflammation, conditions that adversely affect mental health. Psychological pathways include provision of cognitive resources for coping with psychosocial stressors. Social and environmental factors include influences on the intrauterine environment (reducing maternal alcohol and drug use and maternal stress, increasing marital harmony and support), enhancement of early parent–child nurturing, provision of social support that may help to buffer life stressors, and increasing prosocial peer involvement (reducing likelihood of substance use, teenage pregnancy and school drop-out). Finally, greater religiosity may influence individual decision-making across the lifespan by instilling moral and ethical values that foster prosocial choices, thereby enhancing mental health, and discourage deviant or antisocial choices that lead to incarceration, job loss, poverty and other situations that contribute to mental illness. This does not mean that religious involvement always has positive effects through these pathways, and in select cases the opposite may occur. Religious participation can also cause guilt, anxiety, discrimination or abuse.

FIG 1 Pathways by which religious involvement may affect mental health and well-being (Koenig Reference Koenig2018b: p. 160; used with permission).

The mechanisms reported here concern averages over all positive and negative experience, but of course individual experience may vary. Nevertheless, systematic research, both past and more recent, generally provides support for these pathways.

Clinical applications

The spiritual/religious history

Professional psychiatric organisations (e.g. the American Psychiatric Association, Royal College of Psychiatrists and World Psychiatric Association) recommend that patients' religious beliefs and practices be taken into consideration when providing psychiatric care. Typically, this is accomplished by taking a spiritual/religious history on initial assessment (Table 1). If religious beliefs are not clearly pathological and appear to be helping the patient to cope with traumatic situations or distressing symptoms, then the clinician may decide to support or encourage them (or at a minimum, show respect for, and provide psychiatric care in light of, those beliefs). In Middle Eastern cultures, strong religious beliefs against suicide are particularly protective (Shaheen Al-Ahwal Reference Rosmarin, Bigda-Peyton and Öngur2016), making the assessment of religiosity (Al-Zaben Reference Al-Zaben, Sehlo and Khalifa2015) essential among Muslim patients with major depressive disorder or other high-risk mental disorders. However, a spiritual history will be more relevant in some medical (e.g. life-threatening illness) and psychiatric settings than in others.

Religiously accommodative treatment

If the patent is clearly religious, prefers a religiously integrated form of psychotherapy and the mental health professional is prepared to provide such therapy (or knows someone who is), then this approach to treatment may be considered. Religiously integrated cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is effective in the treatment of major depression, especially among individuals who are highly religious (Koenig Reference Koenig, King and Carson2015). Therapist manuals and patient workbooks in Christian, Jewish, Muslim (Shia and Sunni), Hindu and Buddhist versions are available to download free of charge on the Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health website (https://spiritualityandhealth.duke.edu/index.php/religious-cbt-study/therapy-manuals).

A recent meta-analysis of religiously accommodative therapies that included 97 outcome studies involving 7181 patients found that religiously/spiritually adapted therapies resulted in greater improvement in psychological functioning compared with no treatment (effect size g = 0.74, P < 0.000) or with secular psychotherapies (g = 0.33, P < 0.001) (Captari Reference Bradshaw, Ellison and Fang2018). Religiously integrated psychotherapies appear to be at least as effective as standard psychotherapies in the treatment of emotional disorders, and perhaps more effective in highly religious patients. Alternatively, clinicians may decide to refer a patient to a trained licensed pastoral counsellor. Providing secular therapy and/or pharmacological treatment together with a pastoral counsellor is another option. (See Khokhar Reference Khokhar, Dein and Qureshi2015 for further information on prescribing and religious dietary requirements.). Bear in mind, however, that spiritual or existential distress may be present in patients who do not identify as ‘religious’ and may require clinical attention.

The spectrum of religious beliefs

Psychiatrists must be able to distinguish healthy religious beliefs from pathological religious beliefs due to an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia, delusional disorder, major depression with psychosis, or mania in bipolar disorder. Religious beliefs exist on a spectrum from normal and healthy to delusional and psychotic. Deciding where on that spectrum an individual's beliefs lie may not be easy. There are several ways to distinguish whether a patient's religious beliefs are a resource for enhancing mental health or a liability that contributes to psychopathology. First, family members, friends and members of the patient's religious community can usually tell whether the individual's religious beliefs/behaviours are within or outside the normal range for their faith tradition, thus requiring clinicians to obtain collateral information from these sources. Second, people with underlying neurotic or psychotic disorder usually have other symptoms of the disorder that accompany religious beliefs. For example, a person with a psychotic disorder usually has other symptoms of thought disorder or behavioural problems. Third, an ongoing assessment of the patient's beliefs across multiple visits may be necessary to determine the pathological nature of beliefs, religious or otherwise. Finally, the clinician should attempt to determine whether religious beliefs are being used in a way that blocks healthy changes in attitude or behaviour that may be necessary for symptom and functional improvement. This is perhaps the most difficult task, since mental health professionals' own religious beliefs (which may be different from those of the patient) or non-belief may cause difficulty determining whether a patient's religious beliefs are functional or not. Thus, when dealing with religious and spiritual issues in therapy, countertransference and boundary issues must be considered. Although clinicians often cite a lack of training on how to address religious/spiritual issues as a reason for not doing so, such training is readily available (e.g. https://spiritualityandhealth.duke.edu/index.php/cme-videos).

Conclusions

The evidence base is rapidly growing on the relationship between religion and mental health, the links between religious beliefs and psychiatric disorder and the efficacy of religiously integrated psychotherapies for religious patients. There is much recent research that demonstrates that religious involvement can serve as a resource that enhances individuals' mental health and well-being and can prevent the development of mental disorders or speed their resolution. Much further research is needed, particularly RCTs that examine the efficacy of religiously integrated treatments in different religious belief systems, with different patient populations and in different regions of the world, given the impact of historical and cultural factors. Although there is little doubt that religion can be pathological and at times is used in unhealthy ways, the increasing volume of systematic quantitative research now available indicates that the days when every form of religion was automatically considered pathological or neurotic should be over. Patient-centred care that takes into consideration patients' cultural and religious background is increasingly becoming a standard for good clinical practice. However, more research is needed on how to best assess and utilise patients' religious beliefs in clinical practice.

BOX 2 Taking a religious/spiritual history for clinical assessment

1. ‘Do you consider yourself a religious or spiritual person or neither?’

2. If religious or spiritual, prompt: ‘Explain to me what you mean by that.’

3. If neither religious nor spiritual, ask: ‘Was this always so?’ If no, ask: ‘When did that change and why?’ [Then end the spiritual history for now, although you may return to it after a therapeutic relationship is established]

4. ‘Do you have any religious or spiritual beliefs that provide comfort?’

5. If yes, prompt: ‘Explain to me how your beliefs provide comfort.’ If no, ask: ‘Is there a particular reason why your beliefs do not provide comfort?’

6. ‘Do you have any religious or spiritual beliefs that cause you to feel stressed?’

7. If yes, prompt: ‘Explain to me how your beliefs cause stress in your life.’

8. ‘Do you have any spiritual or religious beliefs that might influence your willingness to take medication, receive psychotherapy, or receive other treatments that may be offered as part of your mental healthcare?’

9. ‘Are you an active member of a faith community, such as a church, synagogue or mosque?’

10. If yes, ask: ‘How supportive has your faith community been in helping you?’ If no, ask: ‘Why has your faith community not been particularly supportive?’

11. ‘Tell me a bit about the spiritual or religious environment in which you were raised. Were either of your parents religious?’

12. ‘During this time as a child, were your experiences positive or negative ones in this environment?’

13. ‘Have you ever had a significant change in your spiritual or religious life, either an increase or a decrease?’ If yes, prompt: ‘Tell me about that change and why you think it occurred.’

14. ‘Do you wish to incorporate your spiritual or religious beliefs in your treatment?’ If yes, ask: ‘How would you like this to be done?’

15. ‘Do you have any other spiritual needs or concerns that you would like addressed in your mental healthcare?’

(After Koenig Reference Koenig2018b: p. 342; used with permission)

Author contributions

All three authors contributed to the conception and design of this article, helped to draft and revise the work, providing important intellectual content, approved the final version of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of this work in terms of its accuracy and integrity.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 The best evidence for a protective effect of religiosity on mental health is for:

a schizophrenia and other psychoses

b anxiety disorders and PTSD

c depression

d substance use disorders

e suicide.

2 Research showing a positive effect of religiosity on marital/family stability, social support and psychological well-being is important because:

a it provides evidence for religiosity's impact on mental health resiliency

b it proves that religion is always good for mental health

c religious beliefs and practices cannot be neurotic

d psychiatrists should not get involved in such matters

e religious people are always happier than those who are not religious.

3 Moral injury:

a is a syndrome that cannot be separated from PTSD

b has few effects on other aspects of mental functioning (depression, anxiety, suicide, substance misuse)

c includes both psychological and religious symptoms

d has no effect on treatment response in PTSD

e is now being recognised and treated by most psychiatrists.

4 The most important application of religion in clinical practice is:

a seeking to convert patients to the psychiatrist's religious beliefs

b always encouraging patients to be more religious

c always discouraging religious involvement among religious patients

d taking a religious/spiritual history

e telling patients about research showing that religion is good for their mental health.

5 Psychiatrists should always:

a learn and administer religiously integrated cognitive–behavioural therapy to all patients

b pray with all patients after a visit

c show respect for patients' religious beliefs

d have patients memorise religious scriptures to help them with their mental problems

e ignore patients' religious or spiritual beliefs.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 a 3 c 4 d 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.