Article contents

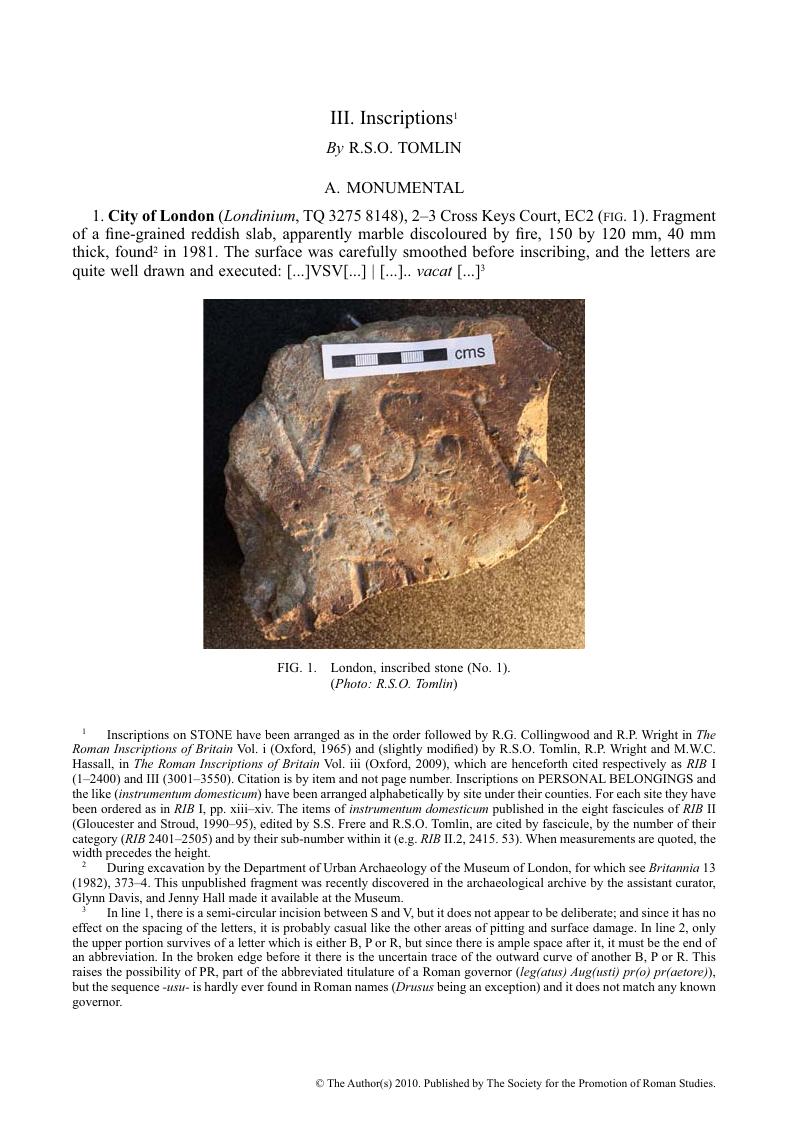

III. Inscriptions1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 September 2010

Abstract

- Type

- Roman Britain in 2009

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s) 2010. Exclusive Licence to Publish: The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

Footnotes

Inscriptions on STONE have been arranged as in the order followed by CollingwoodR.G. and WrightR.P. in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford 1965) and (slightly modified) by TomlinR.S.O. R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall, in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), which are henceforth cited respectively as RIB I (1–2400) and III (3001–3550). Citation is by item and not page number. Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB I, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505) and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415. 53). When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

References

2 During excavation by the Department of Urban Archaeology of the Museum of London, for which see Britannia 13 (1982), 373–4. This unpublished fragment was recently discovered in the archaeological archive by the assistant curator, Glynn Davis, and Jenny Hall made it available at the Museum.

3 In line 1, there is a semi-circular incision between S and V, but it does not appear to be deliberate; and since it has no effect on the spacing of the letters, it is probably casual like the other areas of pitting and surface damage. In line 2, only the upper portion survives of a letter which is either B, P or R, but since there is ample space after it, it must be the end of an abbreviation. In the broken edge before it there is the uncertain trace of the outward curve of another B, P or R. This raises the possibility of PR, part of the abbreviated titulature of a Roman governor (leg(atus) Aug(usti) pr(o) pr(aetore)), but the sequence -usu- is hardly ever found in Roman names (Drusus being an exception) and it does not match any known governor.

4 During excavation in advance of constructing a coach park for the Celtic Manor Resort, of which Mark Lewis sent details. He also made the stone (MT 30-10-09, 002 and 003) available in Caerleon Roman Legionary Museum.

5 In line 1, only the tip survives of the first letter, but A looks more likely than M or R. After C only the bottom of a vertical stroke survives, which in view of the letter-sequence is probably I or T. In line 2, I is ligatured to N. The next letter is probably Q, with its tail lost in the damage, but O is possible. The absence of any spacing makes […]nio Vo[…] (part of a name) or […]ni quo[…] unlikely, but the adjective iniquus in the ablative case is an attractive reading, since it suggests the metrical tag fato … iniquo (‘by unfair fate’) found in epitaphs. There is no British example, but compare RIB 684 (York), spe captus iniqua (‘victim of unfair hope’).

6 By George Beckwith of Brough Castle Farm, in whose possession it remains. It was reported by Nicola Gaskell of North Pennines Archaeology, and Mr Beckwith made it available.

7 In line 1, H and E are ligatured. The letters CH in Latin usually transliterate Greek chi, so this is likely to be part of a personal name. If it ended here, it would be feminine, either Psyche or one compounded from -tyche such as Eutyche. In line 2, only the apex survives of the first letter, but A, not M, is required by the ligatured NT which follows. […]ANT is probably part of another personal name, the likeliest being Ant[onius] (etc.), since an unabbreviated verb ending in -ant (present tense, 3rd-person plural) is unlikely in an epitaph.

8 With the next five items during excavation for the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley. Robin Birley made them available, with details of provenance. The altar has now been removed to the site museum, but will be replaced in situ by a replica. All three altars (Nos 4, 5 and 6) are published with full commentary by Andrew Birley and Anthony Birley in ‘A Dolichenum at Vindolanda’, Archaeologia Aeliana forthcoming, of which Anthony Birley sent a copy.

9 The mis-spelling Dolochenus (for Dolichenus) is rare, but is found at Risingham (RIB 1220) as well as Rome (ILS 4314) and Sacidava (AE 1998, 1144). The prefect is unattested, but can be identified with the prefect of the same cohort who dedicated RIB 1688 (Staward's Pele, four miles SSE of Vindolanda); see further below, Addenda et Corrigenda (a). The cohort is first attested at Vindolanda in a.d. 213 (RIB 1705).

10 The dedication is lost, but in view of where the altar was found, it was presumably Jupiter Dolichenus. The approximate number of letters lost in lines 1 and 2 can be calculated from the known width of the die and the spacing of letters in 3. The prefect's cognomen undoubtedly began with V, and the spacing is appropriate to V[ictor], so it is tempting to identify him with Decimus Caerellius Victor, prefect of the same cohort, who dedicated an altar to Cocidius (RIB 1683) which was found within two miles of Vindolanda. But the nomen is lost, and other cognomina in V- would fit the space, so the identification is not certain. The right margin of line 3 is lost, but there would not have been room for VM in the cohort-title (Nerviorum) even if ligatured. The cohort's movements are discussed by Anthony Birley (see n. 8 above); the only other evidence for its presence at Vindolanda is a stamped tile (No. 67 below).

11 Lines 1–2 are quite uncertain. The vertical score down the left margin makes it unclear how much text, if any, has been lost. At the beginning of both lines, there is a diagonal mark which if intentional would suggest ‘open’ A. But there are two such marks at the beginning of line 3, as if for M, which would be redundant to the V S L [M] formula that follows. So these marks might all be casual. In line 1, the mark is followed by a square outline like an inverted L; then after EX, there are three pairs of diagonal strokes appropriate to AM or MA. In line 2, after RA, the surface is too worn to tell whether M was actually inscribed; the rest of the line seems to be uninscribed. Anthony Birley (see n. 8 above) suggests the personal name A[L]EXAN|[D]RA, but N can hardly be read; alternatively he suggests [A]RA[M] in line 2, a word already found on two informal altars from Vindolanda (RIB 1694, 3341). Except for the find-spot, there is no indication of the god concerned; the capital is too damaged to be sure that it was not inscribed.

12 There are many forms of the name of the god ‘Veteres’, but this is unparalleled: it is an ungrammatical conflation of two already found at Vindolanda, the singular, aspirated form (for example RIB III, 3335, deo Huitiri) with the plural form (for example RIB 3338, dibus Veteribus).

13 Both inscriptions belong to the original quarry-face, not to the building-stone itself, and (ii) is now cut by the left edge of the stone. Flavius, like other ‘imperial’ nomina, is sometimes found as a cognomen.

14 By metal-detector. Daubney No. 46 (see n. 30 below).

15 This is now the best evidence that TOT rings were dedicated to a deity whose name was in the dative case (compare No. 41 below (Fulbeck)), and that this deity was Toutatis. There are several variants of the name, including Totatis. See further, Daubney (cited in n. 30 below).

16 By metal-detector and reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Sally Worrell sent a photograph and other details.

17 The downward extension of the third and fourth strokes of M might be intended for cursive R, but their position implies that they are not a separate letter, but the second half of M clumsily inscribed. A personal name Maia is implied by the name Maianus, which is quite well attested in Gaul, and this interpretation would indicate ‘(property) of Maia’. Alternatively it might be a dedication ‘to Maia’, in Roman mythology the mother of Mercury, but there is no evidence of her cult in Britain.

18 By metal-detector and reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Sally Worrell sent a photograph and other details.

19 Line 1 ends in ‘open’ A, but in the photograph at least it is difficult to read the two vertical strokes which precede it: the first apparently curves at the top, and may even be C; the second lacks the firm cross-bar of T in line 2, and is probably I. To the left of them, at the broken edge, is a dark discoloration which is probably the tip of another letter. The number of letters lost is deduced from the likely restoration of line 2, given that its lettering seems to be closer-spaced. At all events, -ia is a nominative feminine singular ending (since the 3rd-person singular verbal ending in line 2 excludes a neuter plural), and thus terminates an abstract noun or a woman's name. There seems to be no exact parallel for this invocation, but compare CIL xiii 10024.80 (copper-alloy ring), veni vita (‘come, my life’); and for Britain, RIB II.3, 2422.61 and Britannia 38 (2007), 351, No. 8, two copper-alloy rings inscribed veni (‘come’) … (etc.).

20 By metal-detector, as reported by the finder to Adam Daubney (see n. 30 below), in whose catalogue it is No. 45.

21 By metal-detector and reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Sally Worrell sent a drawing and other details.

22 In form and content this sealing is difficult, but is best explained as a blundered reference to the Sixth Legion, which was stationed nearby at York. Unusually for a legionary sealing, it is oval, not rectangular. At first sight the obverse (line 1) names the Fifth Legion, but this was only stationed on the lower Rhine until a.d. 69, and was apparently destroyed soon afterwards. One of its sealings at such an early date in northern Britain is inherently unlikely, especially since the other military sealings found here derive from the British garrison. Both CTR and MAP are easily understood as the abbreviated name of an officer, whether reduced to three initials or two, if the ‘medial point’ in MAP is intentional, but it is strange that two officers should be named. However, VIC (reverse, line 2) with its barred VI is apparently a conflation between the Sixth Legion's numeral (VI) and its cognomen (VIC for Vic(trix)), which suggests that CTR may be a reminiscence of Victrix; and furthermore, that the puzzling V on the obverse (line 1) is not ‘5’ at all, but a conflation between V(ictrix) and VI (‘6’).

23 By metal-detector and reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Sally Worrell sent a photograph and other details.

24 The letters were first sketched with a fine point before the punch was used to make the dots. The final M concludes [V]OTV in line 3, but this does not establish the original width of the plaque, since it would depend on whether M was centred or not. Like the temple itself, for which see Woodward, A. and Leach, P., The Uley Shrines ( 1993)Google Scholar, the plaque was presumably dedicated to Mercury, but his name is now lost, with no sign of it in lines 1 and 2. For other copper-alloy plaques dedicated to him at Uley, see RIB II.3, 2432.6, 7 and 10.

25 With the next item during excavation by Oxford Archaeology, directed by Dan Poore on behalf of Hampshire County Council, immediately north of the area examined by Giles Clarke during 1967–1972. Paul Booth sent full details including a drawing and photograph.

26 The skeleton is too badly preserved to determine the sex, but other grave goods are a gilded silver belt buckle and strap end, and a pair of copper-alloy spurs, one with extant gilded silver mounts.

27 (i) This salutation is quite common, but in Britain has been found only in RIB II.2, 2420.65 (a silver spoon), [be]ne vivas. For the form vene < bene, compare CIL xiii 10024.79 (a gemstone), vene valia [for bene valeas]. This confusion between [b] and [v] is found at Pompeii and across the Roman Empire, but it hardly ever occurs in Britain, and the distinction was still observed when vinum (‘wine’) entered Welsh and Anglo-Saxon, which implies that the very few exceptions such as RIB 1 were Roman imports. See further Colin Smith, ‘Vulgar Latin in Roman Britain: Epigraphic and Other Evidence’, ANRW II, 19.2, at 913 and 915. (ii) This salutation is very common. The elision of the post-tonic vowel in utere is a trivial Vulgarism; for other examples see CIL iii 12031.23 and xiii 10018.18 (ILS 8609k).

28 Compare RIB II.3, 2441.18 (bone plaque, Richborough), […]s vivas. Such pleas for a long life are found on finger-rings from Gaul, for example CIL xiii 10024.91b, diu m(ihi) | vivas (‘live long for me’); 91a, 91c and 91d are similar.

29 By metal-detector, like the next item. Both were reported by P. Liddle to Adam Daubney (see next note), in whose catalogue they are Nos 43 and 44.

30 The next 39 items were found by metal-detectorists, and like all TOT rings except RIB II.3, 2422.38, are inscribed on the bezel, but a detailed description is not practicable here. Details after autopsy if possible, but by report for D 14, 16, 21, 22, 27, 28 and 29, were sent by Adam Daubney, the PAS Finds Liaison Officer for Lincolnshire; see further A. Daubney, ‘The cult of Totatis’, in S. Worrell, K. Leahy, M. Lewis and J. Naylor (eds), A Decade of Discovery: Proceedings of the Portable Antiquities Scheme Conference 2007 (BAR, forthcoming). For easier reference, his catalogue-sequence has been retained here, with catalogue-numbers prefaced by ‘D’ in brackets. The Baston ring (D 66), since it was found in 2010, will be noted in next year's Britannia. For unprovenanced rings, see Addenda et Corrigenda (c). TOT rings from Lincolnshire previously noted are RIB II.2, 2422.36 (Lincoln, D 5) and 39 (Tetford, D 10); Britannia 32 (2001), 396, No. 40 (‘market town’ identified as Market Rasen, D 20); Britannia 39 (2008), 378, Nos 13 (Great Hale, D 2) and 14 (Well, D 30). Two-thirds of TOT rings known (44 out of 68 in Daubney's catalogue, which includes 8 ‘unprovenanced’) come from Lincolnshire, and their distribution apparently reflects the tribal territory of the Corieltauvi.

31 The engraver was illiterate and mistook L for E, or simply did not complete the letter. The inscription, like that of No. 10 above (Hockliffe), indicates that TOT rings were dedicated to a deity.

32 There is one other instance of this spelling (No. 80 below (Caunton)), which may be due to uncertainty over whether to transcribe the Celtic diphthong [ou] as o or u.

33 It is not clear from the photograph whether the second T was actually inscribed.

34 During excavation by MoLAS, for which see Britannia 37 (2006), 418. The site adjoins 14–18 Gresham Street (next three items), and they will be published together. Amy Thorp made the sherds available, and sent copies of the post-excavation assessments.

35 The broken edges are too close to be sure that the graffito is complete, but the sequence APM cannot be part of a personal name unless the letters are Greek (alpha, rho, mu), which would be unlikely in Britain. They are more likely to be the initials of a Roman citizen's praenomen, nomen and cognomen.

36 With the next three items, during excavation by MoLAS for which see Britannia 38 (2007), 288–9, and 39 (2008), 316–17; see also n. 34 above.

37 For other British examples of this abbreviation, see RIB II.7, 2501.439 (Colchester), 440 (Caerleon); II.8, 2503.388 (Mucking). Primus and its derivatives are the most common group of names, but other possibilities include Priscus and Privatus.

38 The most likely is Res[pectus] or Res[titutus], but there are other possibilities.

39 For TOT rings and the cult of Toutatis, see Daubney (cited in n. 30 above). In Britain a silver votive plaque (RIB 219) and a stone altar (RIB 1017) are also known, but the copper-alloy plaque from ‘Hadrian's Wall’ (Britannia 32 (2001), 392, No. 20) is suspect. It is likely that ceramic vessels too were dedicated: compare RIB II.7, 2501.801 (TOT on samian, but not necessarily complete) and II.8, 2503.131 (explicitly TOVTATIS, on a coarseware jar from Kelvedon, Essex). In Gaul, from a likely temple-site of Toutatis, five coarseware sherds with the graffito TOTATES in varying states of preservation are published in Clémençon, Bernard and Ganne, Pierre M. ‘Toutatis chez les Arvernes: les graffiti à Totates du bourg routier antique de Beauclair (communes de Giat et de Voingt, Puy-de-Dôme)’, Gallia 66.2 ( 2009), 153–69CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

40 During evaluation by Pre-Construct Archaeology. James Gerard sent a photograph.

41 The first letter can easily be read as cursive R, which looks better than A (in view of the sequence) or the first two strokes of N (since separated from the third). The penultimate letter does not curve enough for C, but can hardly be anything else, placed as it is between two long downstrokes each of which must be I. The name Criticus is uniquely attested (CIL xiii 5783), but some trace of initial C would be expected here; the graffito is apparently complete, but there is not enough space either side to be quite sure. The name *Riticus or *Riticius is apparently unattested, but might be a variant of Reticus (CIL iii 11968) or Reticius (bishop of Autun in a.d. 314, whose name is transmitted by Gregory of Tours as Riticius); see Holder, s.v.

42 During excavation by York Archaeological Trust, directed by Kurt Hunter-Mann, who sent full details including a drawing and photograph.

43 The obverse and reverse legends and the surrounding figures are the same as those on five of the group of twelve bone roundels found at Toppings Wharf, Bermondsey (RIB II.3, 2440.123–7). The sixth (ibid., 128) reads SEIXTIII | RVFINVS, and three others (ibid., 129–31) read SEXTI with the reverse blank. The remaining two are blank (see Britannia 3 (1972), 358, fig. 21). The association of SEXTIII with SEXTI suggests that the final II is a numeral (‘2’) rather than ‘E’, especially since a feminine reading (Sexti(a)e | Iuni(a)e, whether genitive or plural) would be difficult anyway. Perhaps this numeral differentiated the gaming-counter's rank: according to Isidorus (Orig. 18. 67), the counters (calculi) which moved in a game of latrunculi (‘bandits’) were divided between those which could only move straight (ordine) and those which could move in more than one direction (vagi). The victory-symbolism (palm-branch and wreath), and the figures of a gladiator on one Bermondsey roundel (RIB II.3, 2440.124) and a beast on another (ibid., 128), may allude to combats in the arena, but the significance of Iunii and Sextii is unknown.

44 During excavation for the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley. Robin Birley made it and the next seven items available with note of provenance. Small-find (SF) numbers are given in brackets.

45 It was first interpreted as part of a perpetual calendar, with two days to a hole, by Andrew Birley in Archaeology 62.1 (Jan./Feb. 2009), 72; see also Current Archaeology 224 (Nov. 2008), 14–15, and Birley, Robin, Vindolanda: a Roman Frontier Fort on Hadrian's Wall ( 2009)Google Scholar, col. pl. 23. But Michael Lewis has argued persuasively in Current Archaeology 228 (March 2009), 12–17, that it is part of an ‘anaphoric’ water-clock as described by Vitruvius (9. 8. 8–15); see also M. Lewis in (ed.), O. Wikander, Handbook of Ancient Water Technology ( 2000)Google Scholar, 361–9, and esp. 366. The clock's function was to divide day and night into 12 equal hours each according to the Roman system, whatever the latitude or time of year, by means of a disc which rotated once every 24 hours against a fixed grid. This disc had holes around the circumference which was marked with the months, like the Salzburg fragment (ILS 8645), and the date was marked by means of a peg. As it rotated, therefore, the peg marked the angle of the sun against the grid somewhat like a sun-dial, but working day and night. Since Roman hours of day and night varied in length according to the time of year, the equinox is marked because it was the only 24-hour period (twice a year) in which all 24 hours were of equal length. Time-keeping by the hour would have been essential to the fort's daily routine: Vegetius notes (3. 8) that the night was divided into four watches of three hours each ‘by the water-clock’ (ad clepsydram), and there are hints of such a system in military papyri which refer to ‘the second watch’ (vigiliam ii, in Fink RMR 67) and ‘the ninth hour’ (hora illa non[a] and hora viiii principia […], in Fink RMR 53). At the fort of Remagen in a.d. 218, the prefect even paid for ‘the clock’ (horolegium) to be repaired (ILS 9363).

46 With the next six items. Except for No. 68 (SF 12236), which was found in the via principalis in front of the west granary, they were all found in fourth-century ‘chalet’ barracks, where they must have been residual.

47 The tops of the letters have been lost, so it is uncertain whether the first II was barred to identify it as a numeral. N is reversed. There is no evidence of how far the title Nerviorum was actually abbreviated. Auxiliary tile-stamps are comparatively uncommon (see RIB II.4, 2464–2480), and only three units are known to have abbreviated cohors to C, but in each case (ibid., 2468, 2469, 2471) with a medial point, which is not the case here. For this cohort at Vindolanda, some time in the second century, see No. 5 above (Vindolanda) with note.

48 The stamp is otherwise unknown.

49 The graffito is incomplete, since the cut edge of another letter shows in the break. The first letter might be read as P, since the diagonal does not extend to the next down-stroke, but there is a little evidence for the nomen Ninius (for example CIL vi 22986, 22987), which was perhaps cognate with the Celtic name Ninnos.

50 This is difficult to interpret as a numeral, but to read upwards, MII[…], is also difficult.

51 The first letter is uncertain, although complete, and might be either C, P or S: it consists of a vertical stroke continued by a second stroke rising at a diagonal; the scratch at the foot is apparently casual, like that which cuts LI. This rising (not descending) diagonal makes P unlikely, although the name Pulio is attested (AE 1997, 584). There is one instance of the name Sulio, in Lower Germany (AE 1968, 344), but apparently none of *Culio.

52 An abbreviated personal name, most likely Primus or one of its cognates, but there are other possibilities.

53 This is attested as a Latin cognomen (Kajanto, Cognomina, 223), but might be cognate with the Germanic name Canio (RIB 1483, 3324).

54 The next seven items were found by metal-detectorists, and are inscribed on the bezel. Details after autopsy if possible, but by report for D 37 and 40, were sent by Adam Daubney; see further, n. 30 above. His catalogue-sequence has been retained here, with catalogue-numbers prefaced by ‘D’ in brackets. One TOT ring is already known from Nottinghamshire, RIB II.3, 2422.40 (Willoughby-on-the-Wolds, D 36).

55 For the other instance of this spelling see No. 46 above (Ancaster), with note.

56 With 72 other pieces of hacksilber and 681 fourth-century silver coins (siliquae and miliarenses) closing with Valentinian and Valens in the period a.d. 364–7. The hoard has been acquired by Somerset County Council Museums Service, and is published by S. Minnitt in Abdy, R. E. Ghey, C. Hughes and I. Leins, Coin Hoards from Roman Britain XII ( 2009)Google Scholar, 306–12. See also S. Minnitt and M. Ponting, ‘The West Bagborough hoard, Somerset’, in the forthcoming proceedings of a conference on hacksilber published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Steve Minnitt sent a photograph and full details.

57 No units are given, but this is surely a note of weight expressed in either ‘pounds (and) ounces’ or ‘ounces (and) scruples’, the Roman pound (libra) of 327.45 gm being divided into 12 ounces (unciae) each of 24 ‘scruples’ (scripula). Since the graffito is vertically aligned to the left cut edge, the weight must relate to the hacksilber itself and not to the original piece of silver plate. Conceivably it is the weight of several pieces of hacksilber tied together, but this possibility should be rejected in view of the actual weight of 163.26 gm, which is exactly one half-pound, a semis (regularly abbreviated to s). Although one would have expected s(emis) to have occupied a third line by itself, it looks as if the graffito recorded successive reductions of a piece of hacksilber from one pound to three-quarters of a pound, and then to half a pound.

58 And reported by a metal-detectorist (2009 T640). Information from Adam Daubney (see n. 30 above), in whose catalogue it is No. 67.

59 With the next item during the excavation noted in Britannia 23 (1992), 307–8. Both are recorded there, but were not included under Inscriptions (ibid., 309–23).

60 VALE is inscribed on the lower half of the bezel. The drawing (Britannia 23 (1992), 308, fig. 26) does not specify whether the upper half was originally inscribed or left blank, but comparison with other inscribed rings, and the placing of VALE, strongly suggest that it was originally preceded by bene or perhaps a personal name.

61 Compare RIB II.2, 2419.116 (with note of other examples from Britain and Gaul).

62 With the next item (both SF 245) and other Roman material, during excavation directed by Mrs Heather Sebire. Information from Philip de Jersey, who made the sherds available.

63 Although broken to the left, the graffito is probably complete, with V ligatured to ‘open’ A. The reading [.]MT is just possible, with incomplete M; this would be the name of a Roman citizen reduced to its three initials, but it seems most unlikely. For other examples of the abbreviation VAT, see RIB II.7, 2501.573 (London) and II.8, 2503.598 (Old Winteringham). Possible names are all rare; in Britain they include Vatta (RIB 610) and Vatiaucus (RIB II.3, 2432.4).

64 There is a space between the first letter and the second, and a possible difference in alignment (but not in the instrument used), to judge by the second and third letters. The third letter is a downstroke broken at the top, and is therefore incomplete; it might be II = E, or even N (etc.), rather than I. A note of capacity expressed in two units seems unlikely, but the graffito is too fragmentary to decide between the possibilities of two ownership inscriptions, the first in the genitive case, or of one by a man with two names such as [IVL]I VI[IRI].

65 During excavation by AOC Archaeology Group (project no. 20137). Information from Alex Croom, who sent a drawing.

66 The abbreviation VIIR is quite frequent: it occurs on samian sherds from Richborough (RIB II.7, 2501.598), Leicester (584), Lancaster (816) and Corbridge (817). The name would probably have been Roman in appearance, but have ‘concealed’ the Celtic name-element *vero-s (‘true’). There are many possibilities, but the most likely are Verus, Verinus and Verecundus. Since the first two were hardly worth abbreviating, Verecundus seems likely.

67 As suggested by Robin Birley; the altar was re-examined in 2009 by Anthony Birley (see n. 8 above).

68 During excavation for the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley. Robin Birley made them available, with a note by Anthony Birley which makes the connection with RIB 1705, although his readings differ slightly from those offered here. None of the fragments conjoin, but (i) is the same thickness as RIB 1705 [4½ in. = 115 mm], its lettering is similar (but slightly taller, as appropriate to the first two lines), and like RIB 1705 when found, it retains traces of red paint. Independently of RIB 1705, both fragments can be dated to the sole reign of Caracalla, besides being found in the adjoining building. The text as restored by RIB should therefore be expanded by inserting his elaborate ‘ancestry’, details of which are given by RIB 1202 (Whitley Castle), 1235 (Risingham), etc.

69 The broken edge to the left preserves the middle of S in line 1, and the tips of I (ligatured to H or N) and of C in line 2. Next, I was ligatured to M, although this began the next word; and A (with its cross-bar now lost) was ligatured within M. The adjective maximus (‘greatest’), here probably abbreviated to maxi(mi) as in RIB 1705, line 2, was only added to the last two of Severus’ titles, Parthicus and Britannicus. Either could be restored here, but Parthicus would allow more space in the line for all the preceding titles (Pius, perhaps Pertinax, Aug(ustus), Arabicus and Adiabenicus), which were themselves probably abbreviated.

70 It is too small to be located exactly. Line 1 is either part of Germanici for his ‘grandfather’ Marcus Aurelius, or the end of Hadriani (his ‘great-great-grandfather’) or Traiani (his ‘great-great-great-grandfather’). Line 2 likewise is either the beginning of Ner[vae] (his ‘great-great-great-great-grandfather’ and ultimate ancestor), or part of abnepoti (‘great-great-grandson’) or adnepoti (‘great-great-great-grandson’). In view of the likely line-width, nepoti (‘grandson’) and pronepoti (‘great-grandson’) may be eliminated.

71 By Adam Daubney (see n. 30 above), in whose catalogue they are D 47, 49, 50, 51, 52 and 68. A seventh ring (D 64) is thought not to be from Britain.

72 By Paul Bidwell (as reported by Alex Croom), who reads the penultimate letter as E, not I, because of its three rightward extensions; he compares a complete example from the fort of Eining, which reads SERVES ( Gschwind, M., Abusina: das römische Auxiliarkastell Eining an der Donau vom 1. bis 5. Jahrhundert n. Chr. (Munich, 2004)Google Scholar, 329, C 383 with fig. 46). The complete legend is unknown, but is surely related to the baldric- and belt-fittings which read (in effect) Iuppiter Optime Maxime conserva numerum omnium militantium (RIB II.3, 2429, with Allason-Jones, L. ‘An eagle mount from Carlisle’, Saalburg Jahrbuch 42 ( 1986), 68–9Google Scholar). The genitive ‘of Jupiter’ (Iovis) and the jussive subjunctive (serves) suggests that a prayer for protection is being addressed in respectful terms to an attribute of Jupiter, perhaps his eagle with thunderbolt (compare RIB II.3, 2429.1–6, etc.) or his son, the hero Hercules.

73 Compare the previous item (with note).

74 Cool, H.E.M. and Philo, C., Roman Castleford: Excavations 1974–85, I, The Small Finds ( 1998)Google Scholar, 226 (Fabric 1), 231 with fig. 101.24 and 25, a reference owed by Anthony Birley (see n. 8 above) to the late Vivien Swan. The tiles are now in Wakefield Museum.

75 Tomlin, R.S.O. R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall, The Roman Inscriptions of Britain, III: Inscriptions on Stone found or notified between 1 January 1955 and 31 December 2006 (Oxford, 2009)Google Scholar. All but six were first published in JRS or Britannia, to which a Concordance will be found on pp. 493–9, but readings have now been extended or modified by RSOT, who has added historical and epigraphic commentary with note of present location (etc.), and each is illustrated if possible by a photograph as well as an independent ‘contact’ drawing like those in RIB I. The indispensable assistance of many museums and individuals is acknowledged in the Preface and on p. 5.

76 54 High Street, Barkway. A previous owner worked for Sotheby's during c. 1965/85 (information from William MacKay, FSA), and presumably acquired the fragment when the Lowther Castle collection was dispersed in 1970. See further Sotheby's (London) Sale of Antiquities, Monday 29 June 1970. Lots 167–82 are ‘The Property of the Rt. Hon. The Earl of Lonsdale’, and the second item (of two) in Lot 180 is ‘a fragment of a Roman yellow sandstone Altar carved with half an arch enclosing a brief inscription, a fruit and swag to one side, 20¾ in. high (52.7 cm.) by 28¼ in. wide (71.7 cm.)’. Description and dimensions confirm that this is in fact RIB 1020, viewed upside-down.

- 5

- Cited by