On a fine autumn day in March 1841, a thirty-year-old missionary and botanist named William Colenso was traversing the rugged, densely forested Maungataniwha region in Northland, Aotearoa New Zealand, with his Māori guides, when he happened upon a new species of tree.Footnote 1 ‘I had heard of this species of pine from the Natives’, he wrote to William Jackson Hooker, director of Kew Gardens, ‘but could never obtain a specimen’. After repeated inquiries among the communities through which he passed, he finally ‘gained a name among the Natives’ and found the tree in a locality where he had been told to look. ‘The Tree (for a Pine,) is not large’, he observed, ‘but from the Natives’ account, its principal value should lie in its resisting rottenness. – In appearance it somewhat resembles the Kahikatea, (D[acrydium] excelsum) and … may form a new & connecting genus between Phyllocladus & Dacrydium … Its native name is Manoao’.Footnote 2 In this example, Māori phytonyms represented both the start and end point of Colenso's botanical fieldwork. In communicating as such, Colenso was conveying both his importance as an interlocutor between Māori and European cultures, and by extension the epistemological merit of indigenous knowledge. The missionary – like the Māori plant experts on whom he drew – was one in a long line of imperial ‘go-betweens’, operating far outside the ambit of metropolitan authority, and working to translate commercially and taxonomically pertinent indigenous knowledge into European terms.Footnote 3 Kew placed a high premium on such efforts. Three years after Colenso's letter, Hooker printed an account of the missionary's botanizing endeavours, complete with an editorial vaunting his acquaintance with Māori language and culture as particularly advantageous traits for New Zealand botany.Footnote 4 As the Kew director saw things, indigenous botanical expertise was the indispensable currency of colonial botanical fieldwork.

Reflecting on the state of contemporary interest in Māori phytonyms some forty years later, Colenso denounced the large number of orthographic errors made by naturalists who lacked acquaintance with the Māori language. The name Te-pua-o-te-reinga (‘The flower of Hades (or hell)’) given in Joseph Hooker's Handbook of the New Zealand Flora (1864–1867), Colenso thought, was probably an embroidery of Pua reinga, meaning a ‘flower eagerly laid hold of, grasped, sought after, or desired’. Another called Toumatou, he argued, translated nonsensically to mean ‘thine-our, – or thy-we,–or albus-anus-tuus!’ But Colenso's perspective on this subject had changed over time as well. For, rather than emphasize the value of indigenous plant names for collecting plants, he declared them to be ‘deeply interesting and philologically useful’. He rounded off these observations by lamenting that ‘this pure and ingenious Maori nomenclature’ had degenerated through contact with settlers and was thus ‘daily becoming more contracted and corrupt’.Footnote 5 By implication, such an inoperable reference system had clearly outstayed its utility as a medium of field science inquiry. This was phytolinguistics turned to very different purposes indeed.

This essay concerns this shift from an ethnoscientific to a primarily philological and ethnological perspective on native plant names. I trace this attitude to Alexander von Humboldt, who differentiated between indigenous phytonyms with a merely local provenance to be used as philological data on the one hand, and universally credible Latin plant names on the other. The next section of my argument demonstrates how this way of using indigenous plant names lent itself to a chauvinistic reading of cultural difference. Botanical philology and ethnology, as we shall see, juxtaposed a superficial acquaintance with a large number of vernacular classification systems to a more familiar metropolitan taxonomical standard; tended to consider indigenous phytonyms for their ethnological and phonological affinities rather than their knowledge content; and bore directly, for Indo-Pacific societies especially, on questions of racial hierarchy. I turn next to Aotearoa New Zealand, where, initially, it was observers largely unacquainted with Māori culture or the Māori language (te reo) who embraced this approach. When anthropologists adopted this role for Māori plant classifications in the 1890s, however, they did so with a relatively solid foundation in te reo Māori, personal relationships with a number of Māori individuals, and a general sympathy for Māori culture. This circumstance is testament both to the near-complete exclusion of Māori phytonyms from published works of botany by the early twentieth century, and to the internalization of an essentializing, dehumanizing view of indigenous epistemology amongst otherwise well-intentioned commentators.

This article has several objectives. First, in contrast to a prevailing scholarly emphasis on the marginalization and erasure of indigenous knowledge after Linnaeus, the ensuing pages concern the ways nineteenth-century European scholars of the Indo-Pacific engaged with precisely this subject area – albeit in most cases to markedly colonialist ends.Footnote 6 In particular, I analyse how indigenous plant names have served as what Susan Leigh Star and James Griesemer refer to as ‘boundary objects’, in transit not only between indigenous and European – and colonial and metropolitan – cultural spheres, but also between disciplines: philology and ethnology on the one hand, and botany and biogeography on the other.Footnote 7 In so doing, this essay bears on a line of questioning addressed most notably by Michel Foucault, and more recently by Rens Bod, Julia Kursell and others: the nineteenth-century division of the sciences into natural and human domains of inquiry.Footnote 8 My geographical emphasis on the nineteenth-century Indo-Pacific, and on Aotearoa New Zealand in particular, sheds light on the politics of this disciplinary dialysis in a colonial and imperial context. Where indigenous marginalization hinged on the putative inability of first peoples to discriminate natural from cultural realities, such a bifurcation was, of course, far from innocent. This dovetails with what Anishinaabe linguist Wendy Makoons Geniusz and Linda Tuhiwai Smith, of Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Porou descent, have said respecting the disenfranchising role played by disciplinary partitions of knowledge in colonial contexts.Footnote 9 In the case study discussed below, these partitions authorized a far more value-neutral reception of Latin plant designations among anthropologists than they possibly could have amongst botanists, practitioners of a discipline perpetually vexed with questions of species ontology and nomenclatural priority.Footnote 10 For botanists lacking grounding in te reo Māori, and for anthropologists untrained in botany, meanwhile, native phytonyms came to be seen as anthropomorphic and ineluctably particular designations fated for erasure. Paradoxically, it is to Humboldt, the early nineteenth century's most renowned polymath, I argue, that we must look in order to understand this turn of events.

Isotherms and ethnology

The European use of language as a key to the question of human origins achieved its first flowering amongst seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch explorers who provided some of the earliest European musings on connections between Malayan, Malagasy and Polynesian languages.Footnote 11 Researches aboard Captain James Cook's Pacific voyages provoked renewed interest in these questions by extending the Indo-Pacific relationship to the southerly reaches of Aotearoa. Comparative philological studies in the early to mid-nineteenth century expanded the relationship westward, placing the linguistic and cultural foundations of Malaysians, Tahitians and Aotearoans alike in Sanskrit and ancient India.Footnote 12 By the early nineteenth century, then, Māori, Polynesian and East Asian origins could be studied under a rubric that had truly come into its own.

Vernacular phytonyms, generally speaking, did not feature in these considerations. An important turning point in this respect is represented in the figure of Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859). In setting out on their monumental Spanish American survey, Humboldt, together with his companion Aimé Bonpland (1773–1858), undertook something greater than the disclosure of mere ‘insulated facts’. Rather, as scholars of what has been termed ‘Humboldtian science’ demonstrate, the naturalists lugged a veritable toolshed of instruments to the Americas with the intention of ascertaining general laws from precise measurements of diverse phenomena.Footnote 13 Between 1799 and 1804, the pair travelled extensively in Central and South America, relying throughout on indigenous assistance both for day-to-day necessities and in order to glean acquaintance with plants, animals, minerals and geographical information. This involved perpetual engagement with indigenous terms of reference, including plant names, recounted throughout Humboldt's Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent (1814–1826).Footnote 14 Where these appear, however, they are represented as clearly subsidiary to their Linnaean counterparts. One pigment-producing shrub Humboldt described, for instance, as ‘a plant of the family of the binoniae, which Mr. Bonpland has made known by the name of bignonia chica. The Tamanacks [Tamanaku] call it craviri; the Maypures [Maipure], chirraviri’.Footnote 15 Here, the vernacular terminology's limited purview is signalled by Humboldt's declaration that the plant is merely ‘called’ such by indigenous communities, and by the enclosure of local nomenclature within abstruse familial (Bignoniaceae), generic (Bignonia), and specific (chica) categories. But as Humboldt saw things, it was not wholly that indigenous classifications lacked knowledge-making value in their own right. Europeans also lacked the ability to use them effectively. European commentators, for instance, had carelessly adopted the term ‘ourang outang’ (orangutan) as the Malay designation for Simia satyrus, whereas the term actually referred to ‘any very large monkey, that resembles man in figure’. By ‘continuing to prefer these names, strangely disfigured in our orthography, to the latin [sic] systematic names’, Humboldt argued, ‘the confusion of the nomenclature has been increased’.Footnote 16

These assertions drew upon challenges experienced at first hand. Humboldt and Bonpland were traversing ecologies and societies of extraordinary diversity over the course of a very short period of time. Notwithstanding Humboldt's remarkable versatility in European and Sanskrit languages, there is no evidence that either traveller possessed the requisite expertise to converse freely in any of the indigenous languages they encountered.Footnote 17 In many cases Spanish sufficed. But for inland regions furthest from colonial European influence, it was necessary to obtain translation support through the intercession of Spanish missionaries. This assistance could be difficult to come by where missionaries lacked the amicable cooperation of native peoples. Where available, it could also be problematic. Lacking acquaintance with the Cumanagoto language, for instance, Humboldt simply transmitted missionary observations respecting indigenous nudity, sexuality, beauty, treatment of women and ‘imbecility, which exceeds that of infancy’, in the use of the Spanish language. Even where inquiries could be put to indigenous communities directly, Humboldt observed, individuals often answered with ‘wily politeness’ in the presence of Spanish friars. ‘Travellers cannot be enough on their guard against this officious assent’, he warned, ‘when they wish to support their opinions by the testimony of the natives’.Footnote 18 The lesson was obvious: direct observation, circumventing indigenous mediation, was best.

These deprecations were a prelude to philology. In Humboldt's view, this course of study did not require anything like linguistic fluency. Travellers, he urged, could do their part by compiling lists of words and phrases, in order to help shed light on ‘the essential character of an idiom’. Delineating this ‘character’ involved exploring relationships between languages, assaying their provenance, or laying out their ‘general structure’. In this, Humboldt traded on a framework first propounded by the philologist Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829) and elaborated by his brother Wilhelm von Humboldt. ‘Agglutinative’ languages, both scholars argued, forged meaning by combining autonomous morphemes in sentences, while ‘inflective’ ones accomplished this by modifying root words, such that each part of a sentence bore an imprint of its ‘relation to the whole’.Footnote 19 These modalities were far from equal. ‘The languages formed principally by aggregation’, Alexander wrote, ‘seem themselves to oppose obstacles to the improvement of the mind. They are in fact unfurnished with that rapid movement, that interior life, to which the inflexion of the root is favourable, and which gives so many charms to works of the imagination’. In contrast to Europeans, Humboldt thought, indigenous societies possessed languages and cultures primed for grasping reality as an endless array of experiential particulars. Scholarly interest in these languages, he reasoned, was thus ‘analogous to that inspired by the monuments of semibarbarous nations, which are examined not because they deserve a place among the works of art, but because their study throws some light on the history of our own species, and the progressive display of our faculties’. Even the most refined indigenous languages – at which Humboldt otherwise marvelled – he considered incapable of comprehending ‘treatises of science and philosophy’.Footnote 20 Such ideas were instrumental in establishing what James Morris Blaut terms the ‘rationality doctrine’, whereby ‘primitive’ peoples are seen as ‘incapable of higher theoretical and abstract ideas’ and impeded by ‘languages incapable of expressing higher theoretical and abstract thought’.Footnote 21 As for languages in general, so too for phytonyms in particular. Ill-suited to scientific reasoning – according to Humboldt, who lacked the cultural background to make sense of them – indigenous plant classifications were better adapted to an ethnological function, in helping to explain the order of things according to which they were considered ineligible as works of intellect in the first place.

This onomastic hierarchy is implicit in Humboldt's Essai sur la géographie des plantes (1807). Botanical geography, as Humboldt envisioned it, analysed relationships among plants, and between plants and their environments, rather than the minute study of individual species characteristic of Linnaean natural history.Footnote 22 The resulting treatise provided a multitude of conceptual tools for analysing plant distribution and related problems, including solar refraction, sunlight intensity, air pressure and temperature, atmospheric electricity, geology, aesthetic impressions and isothermal altitude and latitude, whereby species and genera at higher elevations in the tropics were often the same as or similar to those at lower elevations in more temperate latitudes. These climatic variables tended to favour what Humboldt referred to as ‘social plants’ – plants which grew in densities that crowded out competing species.Footnote 23 The anthropomorphism was no accident: plant and human geography, Humboldt sought to establish, were inextricable.

The connection was most conspicuous in the plants that human societies themselves introduced. Such introductions were imperative for loftier and more northerly climes, which tolerated a narrower range of plants, and wherein humans could expect to find fewer useful species that grew of their own accord. Accordingly, Humboldt considered the ‘civilization of peoples’ to be ‘almost always in inverse relation to the fertility of the soil they occupy’. Europeans also atoned for their less spectacular flora by enjoying ‘in thought the picture of faraway regions’. A reader could thereby ‘without leaving his home, appropriate everything that the intrepid naturalist has discovered’. ‘This is no doubt how enlightenment and civilization have the greatest impact on our individual happiness’, Humboldt concluded, ‘by allowing us to communicate with all the peoples of the earth’.Footnote 24 In this view, Europe's intellectual virtues were inseparable from superior systems of reference that set such appropriations on their transglobal, transtemporal, and transcultural circuits with infallible precision.Footnote 25

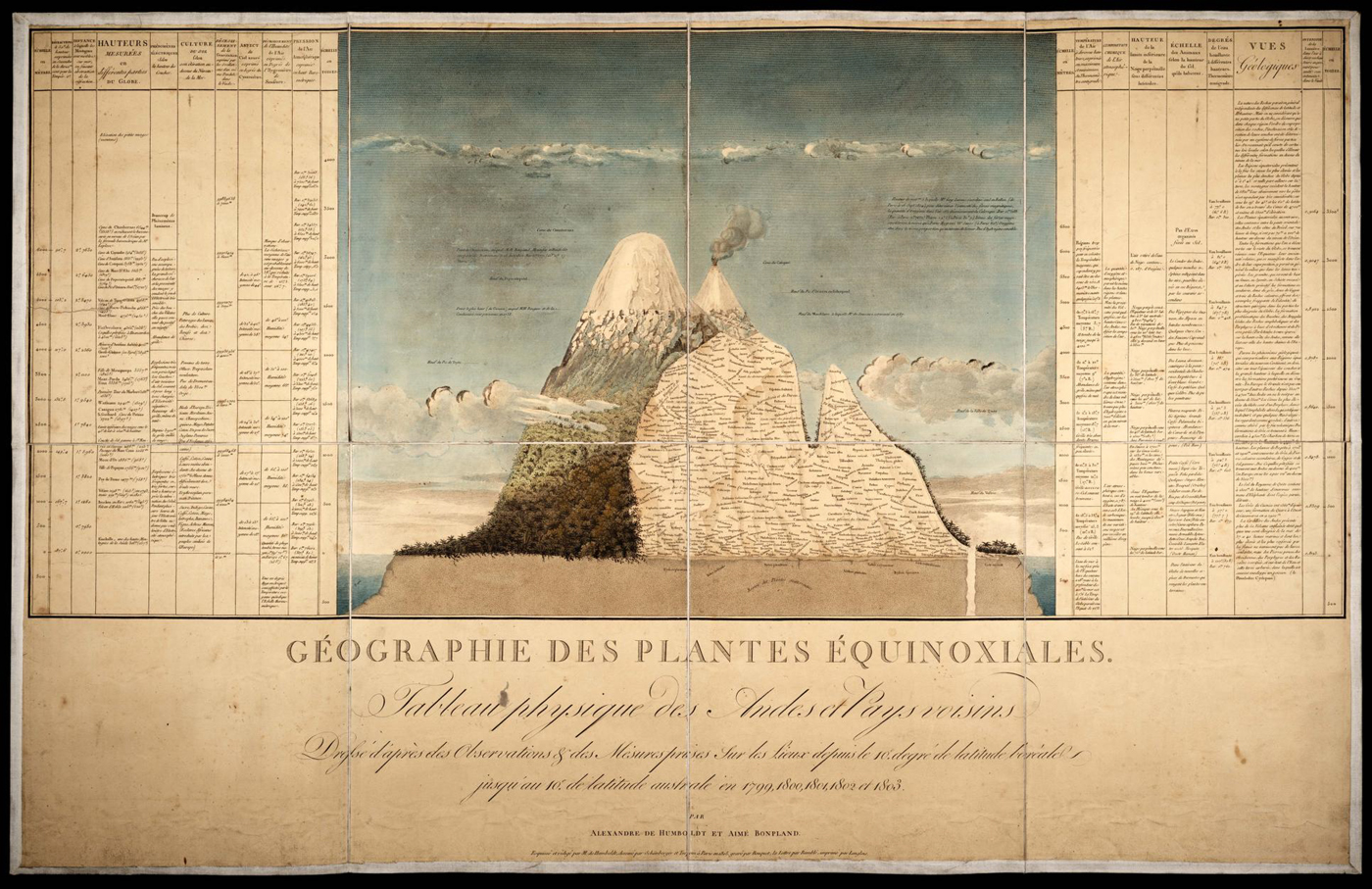

The most notable feature of the Essai is a visual tableau illustrating these referential standards as they related to plant geography (Figure 1). At the center is a two-dimensional likeness of Mount Chimborazo, flanked by columns giving intelligence keyed to elevation, including temperature, atmospheric pressure, humidity, light intensity, horizontal refraction, gravitational pull, geology and characteristic fauna. But perhaps the most conspicuous aspect of the representation is the assortment of generic and specific phytonyms inscribed onto the right-hand two-thirds of the mountain-face. Names written diagonally signified altitudinal habitat ranges, binomials designated species, and genera denoted clusters of related species growing at similar elevations.Footnote 26 Unsurprisingly, no vernacular names feature here. ‘The progress of the geography of plants’, Humboldt declared in Personal Narrative, ‘depends in a great measure on that of descriptive botany; and it would be injurious to the advancement of the sciences to attempt rising to general ideas, in neglecting the knowledge of particular facts’.Footnote 27 And according to Humboldt, only Linnaean nomenclature afforded ‘particular facts’ sufficiently durable to be used in this way.Footnote 28

Figure 1. ‘Tableau physique des Andes et Pays voisins’, in Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland, Essai sur la géographie des plantes, Paris: Levrault et Schoell, 1805.

Humboldt did propose one use for indigenous phytonyms. The association of cultivated plants with such an itinerant species as human beings made their origins especially difficult to ascertain.Footnote 29 But vernacular names, he argued in Personal Narrative, often held clues to their provenance. He illustrated this idea with a list of phytonyms and related terminology that had passed into Spanish usage since the end of the fifteenth century. Most, like ‘Ahi (capsicum baccatum), batata (convolvulus), bihao (heliconia bihai), [and] caimito (chrysophyllum caimito)’, were of Taínan or Caribbean origin. Others, wrongly assumed to be Taínan, turned out to be from elsewhere. ‘Banana’, for instance, originated in the Mbayá language thousands of kilometres to the south, while ‘arepa (bread of manioc, or of the jatropha manihot)’ turned out to be from the Amazonian lowland Cariban languages. As-yet-untraced designations like ‘papaja (carica)’ and ‘aguacate (persea)’, on the other hand, connoted the existence of as-yet-undiscovered peoples.Footnote 30 However dubious Humboldt considered vernacular plant names to be from a strictly botanical standpoint, then, they held intriguing possibilities for anthropology and phytogeography.

In conjoining botany, geography and comparative linguistics in a common programme of research, botanical philology represents a quintessential Humboldtian science. As originally formulated, however, such a venture was utterly incompatible with taking indigenous cultures seriously on their own terms. ‘In languages, as in every thing in nature that is organized’, Humboldt wrote, ‘nothing is entirely isolated, or unlike. The farther we penetrate into their internal structure, the more do contrasts and decided characters disappear’. ‘It might be said’, he continued, citing his brother Wilhelm, ‘that they are like clouds, the outlines of which do not appear well defined, except when they are viewed at a distance’.Footnote 31

From plant geography to human variety

Apperceiving philological clouds, of course, meant overlooking their constituent vapours. Humboldt's ethnological approach would thus prove attractive to commentators who adopted a comparably studied detachment from the peoples they purported to study. And nowhere did Humboldtian ethnology find a more sympathetic hearing than among scholars of the Indo-Pacific. The dispersed, insular nature of this vast region, encompassing richly diverse cultures and flora, comprised an ideal laboratory for European investigations surrounding human and floral origins, migrations, extinctions and diversification.Footnote 32 One such scholar was a Scottish physician and linguist named John Crawfurd (1783–1868), who drew upon his experience as a high-level East India Company administrator in Penang to write his monumental History of the Indian Archipelago (1820).Footnote 33 Therein, he argued that the islands’ history could be understood primarily with reference to the dynamic interaction of two aboriginal races: a superior ‘fair or brown complexioned race’ and an inferior ‘negro race’.Footnote 34 Crawfurd cited Humboldt widely, going so far as to dedicate his later Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language (1852) to both brothers von Humboldt.Footnote 35

The younger Humboldt's guidance is particularly evident in Crawfurd's analysis of the names of useful plants to determine racial origins. The uniform nomenclature for rice and rice agronomy across the Indo-Malayan world, for instance, demonstrated ‘that one improved tribe taught and disseminated’ this method of sustenance. The sago palm contributed a similar kind of evidence. The plant bore many different appellations in the eastern archipelago, while western islanders invariably called it by the same name – sagu – implying that Westerners ‘took the name of the commodity in its familiar commercial form’. In addition to plants and their modes of cultivation, Crawfurd also claimed to discern in language the migration of technologies – of the loom, for instance, from Polynesia to Java, and of advanced cotton manufacture from India eastward.Footnote 36 Ethnological generalizations followed. Drawing on his correspondence with Schlegel and the elder Humboldt, Crawfurd contrasted Sanskrit and Polynesian tongues with a Javanese language that, he thought, could communicate empirical truths but not abstract or general ones.Footnote 37 Technological diffusion was closely bound up with epistemological differences.

That Crawfurd did not relate this purported inability to generalize to Javanese plant knowledge may have been because he was not concerned with botany per se. What botanical names he was able to learn appear to have come via correspondence with botanists like Robert Brown, George Bentham and Nathaniel Wallich, whom he credits in the preface to the Grammar and Dictionary. ‘[T]o the unsuspecting public’, he wrote to Bentham, thanking him for supplying a pair of Latin names, ‘I shall seem to be learned at your expense’.Footnote 38 Crawfurd thus provides an intriguing case study in what Brent Henze identifies as a key aspect of ‘emergent’ disciplines like nineteenth-century ethnology, which adapt elements and strategies from other sciences in order to secure rhetorical credibility.Footnote 39 The indigenous and Latin plant names employed in Crawfurd's analyses also exemplify what Star and Griesemer have defined as ‘boundary objects’, or ‘scientific objects which both inhabit several intersecting social worlds … and satisfy the informational requirements of each’. They are ‘both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites’.Footnote 40 Crawfurd lacked comprehensive acquaintance with either Indo-Malayan or metropolitan botanical classifications. Nonetheless, he shrewdly translated both systems to meet his needs, adapting Latin phytonyms as markers of credibility, and laying hold of indigenous names as indicators of diasporic botanical and racial histories. Similar interdisciplinary borrowings are discussed later in this essay.

Crawfurd's examination of Indo-Pacific vocabularies for what they could reveal about natural and human histories, rather than for knowledge considered useful in its own right, cannot be seen apart from his racial politics. His early work, drawing inspiration from his mentors von Humboldt, had divided the world into distinctly greater and lesser varieties of the human species; pace the Humboldts, this later became a confirmed polygenism.Footnote 41 This latter school of thought, which ranked human races according to their ostensibly separate biological origins, garnered attention in opposition to – among other things – influential monogenists like James Cowles Prichard, missionary evangelicalism, and popular abolitionism, culminating in Britain's Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.Footnote 42 Crawfurd's position is most categorical in an 1868 paper discussing the heterogeneity of cereal nomenclature. ‘In so far as philology can be considered evidence’, he argued, ‘this fact would seem to show, not that the culture of the cereals had originated at a single point, from which they were in course of time widely disseminated, but at many separate and independent points’.Footnote 43 This application of native plant names is a late nineteenth-century instantiation of a process Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra has analysed for the Enlightenment and early nineteenth century, whereby indigenous testimony ceased to be seen as empirically valuable, and came to serve instead as evidence in dubious conjectural histories of human development.Footnote 44 Indeed, if Crawfurd is any indication, culturally inarticulate usage of indigenous botanical vocabularies could lend viability to the wildest racial hypotheses.

This kind of thinking almost certainly influenced the nineteenth century's foremost proponent of botanical philology: the French Swiss botanist Alphonse de Candolle (1806–1893). Owing to his father's role in developing the natural system of botanical classification, and to his own Lois de la nomenclature botanique (1867), Candolle's name is virtually synonymous with nineteenth-century systematics and its unapologetically Eurocentric terminology of reference.Footnote 45 Yet his widely read Géographie botanique raisonnée (1855) was also one of the most prominent mid-century botanical undertakings to take vernacular plant names seriously.Footnote 46 These derived from a mammoth four-volume dictionary of popular phytonyms in sixty-seven languages and dialects commissioned by Candolle's father. ‘Botanists’, Candolle complained, ‘have often erred in not learning’ vernacular plant names – a mistake Candolles junior and senior took pains not to repeat.Footnote 47

As we have seen, however, attention to native plant names did not by any means equate to respect for indigenous ways of knowing. Adrian Desmond and James Moore have shown how much of the controversy over the relationship between human races unfolded by way of proxy debates concerning, for instance, single versus multiple sites of floral creation, plant variation and hybridization, and mechanisms of species diffusion (or lack thereof).Footnote 48 Candolle appears to have engaged in these speculations. He explained the presence of identical species separated by seemingly impassable geographical barriers, for instance, by suggesting that many plants had simply been created separately, even if countless others derived from previous forms.Footnote 49 And like Humboldt and Crawfurd, Candolle made no mention of using indigenous phytonyms to help locate rare and valuable plants, or tap into stores of indigenous knowledge, but rather to provide philological evidence of plant dispersal.

Elaborating on this methodology, Candolle observed that the mere existence of a plant somewhere did not prove that it had originated in that place; it might have been transferred by humans, ocean currents or other means. In the absence of reliable eyewitnesses, he urged, ‘it is necessary to observe the nature and number of the names’. With regard to olives, for instance, which have a recorded presence throughout the ancient Mediterranean and Asia Minor, Candolle traced their common names in Spanish and Andalusian (olivo, oliveria, aceytuno, and azebuche), Portuguese (oliveira and zambugeiro), Latin (olea), and Arabic (zaitun), to roots in Greek (ελαια) and Hebrew (zait or sait). Similarly, from the likeness between Polynesian and Malayan names for the taro, Candolle inferred that Pacific Islanders brought it with them on their easterly migrations. As for plums, which grow throughout the Caucasus, Greece and temperate Europe, their heterogeneous popular designations suggested that the species pre-dated human settlement in these areas.Footnote 50 This qualitative and quantitative mobilization of vernacular phytonyms bears a striking resemblance to an analytical technique promoted by Humboldt, Brown, Candolle's father and Alphonse himself under the name of ‘botanical arithmetic’, whereby numerical ratios of plant types were used to elucidate patterns and principles of plant distribution.Footnote 51 By ignoring vernacular plant names’ wider cultural resonance, botanical philology viewed them similarly – as bare numerical data in an imperial and global calculus.

Even so, this method had its challenges. Common names designating a geographic origin, for instance, like blé de Turquie, were often unreliable, though they were frequently correct in indicating at least that a plant was foreign to the area. Other vernacular names, moreover, merely gave the appearance of being locally derived. Many of the phytonyms given in Hugh Davies's Welsh Botanology (1813), for instance, turned out to be simply Welsh translations of English originals. Philological parallels called for especially mindful handling. Where vernacular names resembled Greek or Latin, it could be difficult or impossible to ascertain on linguistic grounds alone whether the popular terminology borrowed from the highbrow or vice versa, and thus whether a species – the chestnut, for instance – emanated from Athens or Rome to the northerly provinces of the ancient world or vice versa.Footnote 52 And lest his enthusiasm for popular phytonyms be interpreted as a preference for their use over scientific classifications, Candolle assured his readers to the contrary. ‘[I]t is a welcome tendency … of modern civilization’, he wrote, ‘to replace the common names of a multitude of languages and dialects with only one name, common to all peoples and founded on well-defined rules’.Footnote 53

These views were shared by a fellow botanist and vernacular plant-name enthusiast named Berthold Seemann (1825–1871). But whereas Candolle based his views on what he could glean from his herbarium and library in Geneva, Seemann boasted a plant-collecting résumé of truly global proportions. Based on his experience as botanist aboard HMS Herald (1847–1851), which touched at locations in North, South and Central America, as well as a number of Indo-Pacific locales, Seemann advocated forcefully for the use of vernacular plant classifications in helping to locate plants. ‘By simply asking the native name’, he wrote, one could ‘instantly have the scientific appellation … The vernacular nomenclature is less fallible than it is generally supposed’.Footnote 54 Seemann's interests in economic botany suggest a pecuniary component to these concerns.Footnote 55 But Seemann was also a keen Humboldtian, who went so far as to name his German-language botanical periodical Bonplandia after the Prussian naturalist's well-known fellow traveller. Like his paragon, Seemann's transient labours left scant time for attaining proficiency in any of the indigenous languages he encountered. Over the course of four years, he managed only four months’ stay in Panama, followed by explorations in Peru, Ecuador and western Mexico, and finally western Canada and present-day Alaska, before sailing homeward via Hawaii, Sumatra and Hong Kong.Footnote 56 Seemann was particularly impressed by Hawaiians’ use-based acquaintance with the ‘vegetable kingdom’, including their ‘vernacular names for every plant’. But he also insisted on an important caveat. ‘Though specific names exist almost to any extent’ in the Hawaiian language, he wrote, following Crawfurd, ‘yet throughout the language there is a great want of generic terms’. On this basis, he concluded that ‘the Hawaiians have never been a thinking people … for no community has any use for generic terms until it begins to reason’. Given these shortcomings, Seemann looked forward to the displacement of the Hawaiian language with English, which ‘after the extinction of the aboriginal race … will become the vernacular tongue’.Footnote 57

Seemann appears to have brought a similar kind of logic to bear on his review of the Maori–Latin Index (1866) to Joseph Hooker's Handbook of the New Zealand Flora (1864–1867). In his praise for the Index, he chose not to emphasize how it might facilitate the conversion of potentially lucrative indigenous knowledge into European classifications. Rather, Seemann followed Humboldt, Crawfurd and Candolle in underlining the utility of Māori phytonyms to help ascertain ‘not only the exact country whence the New Zealanders emigrated’, but also ‘the spots whence many New Zealand plants were derived’. ‘[F]ew plants of tropical Polynesia’, he explained, ‘are identical with New Zealand ones. Hence but few of their names could be affixed by the first settlers, when … they landed in New Zealand’. In most cases, Māori simply ‘gave the tropical Polynesian names to New Zealand species, which closely resembled in look certain tropical ones with which they were familiar in the cradle of their race’. Aotearoa's first peoples, for instance, affixed the name whau to a plant (Entelea arborescens) with leaves similar to the Polynesian vau, or cotton plant (Gossypium spp.). This implied that ‘the Maoris at one time inhabited a country where cotton grew’.Footnote 58 With the Handbook as a foundation, then, Seemann urged botanists ‘not only to persevere in making this “Index” as complete and correct as possible, but also endeavour to obtain, perhaps through traders or missionaries, a list of the vernacular names of Raratonga and Humphrey Island plants, for the purpose of critical comparison’.Footnote 59 This comparative function was far removed from indigenous botanical concerns. As a standardized interface between indigenous and European knowledge systems, however, such an index would serve the intersecting needs of plant-minded European traders, naturalists and ethnologists alike.

Ethnology and botanical philology in Aotearoa New Zealand

Seemann's discussion of Māori and Polynesian phytonyms was a minor entry in a large and growing body of scholarship on Indo-Pacific ethnology. Deriving from a well-known advocate for the use of vernacular plant names, however, Seemann's remarks on Māori phytonyms, which tied them to an enterprise concerned with querying the shared humanity of first peoples, is symptomatic of the diminishing worth attached by Europeans to indigenous knowledge after mid-century. High-profile episodes of resistance to British colonial rule were instrumental in this shift.Footnote 60 Most notable of these was the sepoy uprising in northeastern India from 1857 to 1858, which, as Christopher Bayly describes, was precipitated by a breakdown in communications between Europeans and Indians, which made it impossible for Britons to discern the latitude of grievances against their colonial administration.Footnote 61 In Aotearoa New Zealand, analogous tensions could be traced especially to the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, signed between representatives of the British Crown and a number of Māori chiefs, which sparked a flurry of land speculation and settlement. Disconcerted by the pace of land sales, Māori fought back intermittently until the emergence of the Kīngitanga (Māori king) movement as a focal point of resistance, which set the stage for larger-scale European–Māori conflict throughout the 1860s.Footnote 62 Knowledge flowed less easily across such frontiers. Burgeoning disregard and disdain for Māori cultures and classifications of nature was one result of a world thus partitioned.

South Islanders were especially prone to this view, owing to the large influx of settlers in conjunction with the 1860s Otago gold rush, and the island's comparatively small Māori population.Footnote 63 Foremost among these was an Edinburghian physician named James Hector (1834–1907), who arrived in 1861 to head a colony-wide Geological Survey. Striking into Aotearoa's far north in 1866, Hector was accompanied by several unnamed Māori hired hands, a Māori-speaking European interpreter and the botanist John Buchanan (1819–1898), who had removed from greater Glasgow to Dunedin in 1851. ‘I dont like the Maories [sic] myself’, Buchanan wrote at Kororāreka, ‘and would give them a wide berth at all times if I had my way’. Indeed, as emissaries of the colonial government in vexing political circumstances, and given their lack of familiarity with Ngāpuhi norms and the Māori language, Hector and Buchanan would have been especially susceptible to European anxieties and cultural priorities. These sentiments were not helped by what Buchanan called a ‘scrape’ resulting from a ham-handed decision to camp on tapu (sacred and restricted) ground, such that ‘none of the natives would have any dealings with us or touch our things’, as Hector reported. As both men lightheartedly observed, the ensuing tension meant not having to give up any trade goods; it also deprived the expedition of valuable assistance in locating plants.Footnote 64 Appropriately, the campaign was largely a botanical failure.Footnote 65 Buchanan's discomfort spent itself in a number of disparaging remarks. ‘I don't believe the Maori is a step in advance of what he was in Capt Cooks [sic] day’, Buchanan wrote, ‘he is worse perhaps in some points’. One indicator of this worsening position, he thought, was the unexpectedly low number of Māori individuals descried on the trip. With acerbic humour, Buchanan expressed a

hope that if we advance rapidly on the North Cape we may see the last mob [of Māori] tumbling into the sea as they have disappeared before Dr. Hector as chaff before the wind in the North; the Government ought to send him to the East Coast and save the country the expense of a protracted war with a savage myth.Footnote 66

Certainly, the remark suggests a dual meaning, in alluding not only to the failure to encounter large Māori numbers, but also to the image of a superior, scientific epistemology displacing its indigenous counterpart.

In this, Buchanan may have taken cues from Hector, who was evidently coming around to something resembling the philological method championed by Crawfurd, Candolle and Seemann. It may have been a pair of lectures on Māori and Polynesian ethnology attended by Hector during a visit to England in 1875 that primed him to see Māori plant knowledge in this light.Footnote 67 In any case, when, on a visit to Taranaki a few years later, Māori guides directed Hector's attention to an unfamiliar species of tree they said had come from Hawaiki, and which they had named tainui after the canoe it arrived in, Hector saw an opportunity. ‘I need hardly point out’, he enthused, ‘that if it were true, and we could hereafter determine the original habitat of this tree, it might give us a clue to the whereabouts of the mythical Hawaiki, or the place whence the Maori originally migrated to New Zealand’.Footnote 68 As Hector was surely aware, Tainui iwi had been the foundation of the Kīngitanga movement during the recently concluded military struggles.Footnote 69 The significance of botanical philology in providing a purportedly global framework for interpreting indigenous testimony, at odds with the formation of more rooted understandings and affiliations, and thereby instrumental in the dispossession of Māori lands and resources, would not have been lost on him.

Like the other figures mentioned above, Hector approached Māori ethnology as a linguistic and cultural outsider. Increasingly, however, this perspective would extend to observers better acquainted with Māori peoples and te reo Māori. In addition to the 1860s military conflicts, an important catalyst in this shift was the appearance – in English – of Alphonse de Candolle's Origin of Cultivated Plants (1884).Footnote 70 Expanding on Candolle's earlier work, the volume placed greater emphasis on the analytical shortcomings of vernacular plant names, urging particular caution where they emanated from ancient works and unwritten languages. Moreover, it ranked philology last as a method of seeking out plant origins, after archaeology, botany and history, and drew a pointed contrast between botanical and archaeological ‘facts’ on the one hand and mere historical and philological ‘words and phrases’ on the other. But Candolle's belief that one need not possess anything more than ‘an ordinary general education’ in order to use phytonyms in this way would resonate loud and clear with many readers, as would the application of this method throughout the book's over four hundred pages.Footnote 71

One of these readers was the Suffolk-born Stephenson Percy Smith (1840–1922) (Figure 2), who emigrated to New Plymouth in 1850 and began his surveyor training a few years later. Learning te reo from his Māori workmates enabled him to converse with elders who taught him ‘the names of every plant growing in the forest’.Footnote 72 Smith would bring this skill set to bear on the Polynesian Society, which he co-founded with Edward Tregear (1846–1931) in 1892, and which – as he declared in a promotional circular – sought to collect and preserve all things pertaining to ‘Polynesian anthropology, ethnology, philology, history, manners, and customs of the Oceanic races’.Footnote 73 The demographic plight of Māori peoples, who according to the 1896 census numbered less than forty thousand colony-wide, injected the project with a sense of urgency. Smith, like most settlers, was either oblivious or wilfully blind to the flaws inherent in the 1896 tally, whereby lax governmental standards and pervasive Māori opposition forced enumerators to rely on guesswork or even outright misinformation – defects that tended to result in an overall lower Māori count.Footnote 74 ‘Time was pressing’, he later explained, ‘the old men of the Polynesian race from whom their history could be obtained were fast passing away … to all appearances, there would soon be nothing left but regrets over lost opportunities’.Footnote 75

Figure 2. Elsdon Best (left) and Percy Smith (right), by unknown photographer. Annie Marian Crompton-Smith, ‘Photographs of New Zealand scenes by unidentified photographers’ (1901–1996), Ref: 1/2-028237-F. Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Indigenous plant names helped elucidate this history. Smith was familiar with Candolle already in 1889, when he queried his botanist friend Thomas Cheeseman (1846–1923) whether he thought ‘De Candole [sic] a good authority for the origin of plants’.Footnote 76 Cheeseman, it seems, gave the go-ahead. ‘If’, Smith explained in an article for the inaugural issue of the Polynesian Society's Journal,

we find branches of the race living at opposite ends of the Pacific who have common names for plants identical, or even resembling one another, the inference is certain that those two branches … must at some time have known a plant from which both derived the name, and it follows that they must have inhabited the same place at some time or other.Footnote 77

Smith illustrated this strategy with reference to Futuna, a tiny island approximately halfway between Viti and Tonga. Comparing Futunan plant names and other vocabulary to their synonyms in other Pacific locales, for the most part cribbed from numerous uncited works, Smith inferred that Futunans, like Māori, derived from an ancestral race centered on the ancient Indian archipelago. He would later undertake limited fieldwork outside New Zealand, touring Rarotonga, Tahiti, Ra'iātea, Aitutaki, Samoa, Hawaii and Tonga over the course of a mere six months, but he considered textual materials by and large sufficient for his purposes.Footnote 78 In Smith's view, phytonyms themselves, independent of any wider cultural context, could be used to settle deeply political questions of cultural origins and affinity.

This line of inquiry soon extended to the question of Māori origins more directly. Through meticulous comparison, Smith observed a close affinity between Māori and Tahitian phytonyms, and especially between Māori and Rarotongan classifications. The Hawaiian nomenclature, on the other hand, differed from Māori in the form of similar names applied to widely disparate plant species, or entirely different names for the same plant. From this, Smith inferred that Māori had arrived from Tahiti via Rarotonga, and that Hawaiians arrived from the same via a separate migration. And central Polynesia was just the beginning. Citing Candolle, Smith connected the Telugu term for rice (newaree (nivvāri)) and the Rarotongan word for their ancestral homeland (Atia-te-varinga-nui), which he translated to mean ‘Atia-the-be-riced, or where plenty of it grew’ – Atia, he thought, being India. Candolle's reflections on the South American origin of the kumara (sweet potato) – inferred from the plenitude of vernacular names for the plant found there – feature similarly in Smith's hypothesis concerning the derivation of the Māori word for the plant from its Quechua synonym (umar) via early Polynesian trade.Footnote 79 The Genevan naturalist's convictions respecting the epistemological precedence of scientific botany make something of an appearance as well. Against the inherently fluctuating character of indigenous plant nomenclature, Smith thought, Linnaean phytonyms provided an immutable point of reference. Without these, he argued, ‘no exact comparison can be made with similar names in the other islands’. Once the Polynesian and Malay names of plants were known, then, together with their scientific synonyms, ‘considerable light would be thrown on the whence of the Polynesians’.Footnote 80

Although he adopted Latin phytonyms as an irrefutable premise for his comparative researches, Smith had, by his own admission, ‘no scientific knowledge of Botany’.Footnote 81 What he lacked in terms of necessary expertise to fix the scientific names of plants, he made up in his friendship with Cheeseman. The two men collected and translated for each other. While Cheeseman was gearing up for a botanizing trip to Rarotonga in 1899, Smith requested that he ‘get the native names of all the plants, for that branch has quite an importance of its own’.Footnote 82 Smith did some collecting himself on the island of Niuē, where he was government resident for several months after New Zealand annexed the small western Polynesian country in 1901.Footnote 83 He managed 118 plant specimens for Cheeseman, including most of their indigenous names, and requested that Cheeseman reciprocate by providing their scientific counterparts.Footnote 84 These exchanges are a regular theme in their correspondence into the early 1900s.Footnote 85 For his part, Cheeseman was interested in Māori plant nomenclature primarily for the purposes of an extensive ‘Alphabetical list of Maori names of plants’ under preparation for his Manual of the New Zealand Flora (1906).Footnote 86 Both men, then, placed unstinting confidence in each other's expertise, with Cheeseman accepting the ethnologist's indigenous phytonyms, and Smith adopting the botanist's Linnaean coinages. These exchanges should not be taken to imply a shared expertise. On the contrary, in New Zealand at least, the colonial common ground of proficiency in indigenous and European plant sciences was rapidly dissolving.

Percy Smith was not alone in lending his know-how. Another prominent contributor to the Manual was a close friend of his named Elsdon Best (1856–1931) (Figure 2).Footnote 87 Unlike Cheeseman, Smith and every other major European figure mentioned above, Best was New Zealand-born. Raised just north of Wellington, Best honed his Māori language skills as a farm labourer in Poverty Bay, and later as part of the Taranaki Armed Constabulary. At Parihaka in 1881, with Ngāti Ruanui led by the prophet Te Whiti passively resisting settler intrusions onto unceded lands, Best's unit played an adversarial role in surveying, roadbuilding, forced dispossession and destruction of dissident property. The experience would prove decisive in shaping one of the foremost exponents of Māori ethnology, not least in introducing Best to Smith and Tregear, both then resident in New Plymouth and similarly employed in surveying duties.Footnote 88 A decade later, Best appeared as one of ten founding members at the Polynesian Society's inaugural meeting.Footnote 89 Three years later, when Smith, then surveyor general, went to the Tūhoe-governed Urewera country to superintend the construction of an east–west thoroughfare, he installed Best as quartermaster to give him ‘eyes and ears’ on a people Best would later define as one of the last redoubts of Māori ‘primitive mentality’.Footnote 90 Charged with mediating conflicts between Europeans and Tūhoe leaders, the young official lost no time in cultivating relationships with Tūhoe elders. Drawing on E.B. Tylor's notion of ‘primitive survivals’, and on Friedrich Max Müller's conception of a ‘mythopoeic age’ bereft of abstraction, in which words were inextricable from the things they purported to represent, Best claimed to have discovered residual traces of this way of thinking in the esoteric learning he retrieved from his new acquaintances.Footnote 91

Best also used these circumstances to begin collecting plants. Cheeseman broached the subject in 1898, two years after first commissioning him to gather curios for the Auckland Museum. ‘No, am I am no botanist’, Best replied, though he made sure to add that he studied the Māori names of plants, and had already collected for another botanist named Thomas Kirk (1828–1898).Footnote 92 He would do likewise for Cheeseman. Although his first consignment of specimens with attached vernacular names was ‘spoilt in transit’, he persevered in using his Māori contacts to best advantage. Respecting a clematis specimen he sent Cheeseman a few years later, for instance, his Tūhoe adviser – most likely a man named Tutakangahau (c.1830–1907) – had reportedly told him ‘no, it is an aka [vine] known as ngakau kiore and … bears no flower like clematis but only as seen in spec. Also that it is only found on shrubs and small trees and never on the large forest trees as is the clematis’. Over the course of several months he inquired on the subject of drying paper, books for mounting and labelling dried specimens, and whether Cheeseman had any further advice respecting plant collection and preservation.Footnote 93 Best wound up sending occasional packets of plants over the next few years, together with – in many cases – their vernacular names and uses.Footnote 94 Cheeseman was sufficiently appreciative to gift Best a copy of the Manual and list him therein as one of a number of ‘recent workers’ in botany. Best, for his part, praised the book's ‘enormous amount of matter’, but nonetheless admitted having ‘ever regretted being unable to follow an inclination in the direction of that study’.Footnote 95

This did not prevent him from feigning otherwise. Best prefaced an early chronicle of his Urewera travels, for instance, by describing – in autobiographical fashion – the ‘vivid interest and pleasing anticipation which is felt by the ethnologist, botanist and lover of primitive folk-lore when entering on a new field of research’.Footnote 96 He hinted similarly in a later article on Tūhoe botanical knowledge by declaring that his account was ‘given not by the botanist and ethnographer, but by primitive man. He who evolved the peculiar customs, myths, and superstitions herein described shall tell of them’. But although Tutakangahau is clearly implicated in an extensive list of Māori phytonyms included in the essay, it is the dichotomous framing of the self-titled botanist and ethnographer that predominates. ‘[T]his paper is one dealing with Maori lore’, Best declared, ‘not with that of the scientific botanist’. This was no innocent distinction. The plants known as ‘red manuka and white manuka, as they are often termed by settlers’, and named Leptospermum scoparium and Leptospermum ericoides by botanists, Best explained, were recognized by Ngāi Tūhoe as female and male genders of the same tree – females being those which bore fruit. Of the three classifications – Latin, Tūhoe and settler – Best singles out only the Māori variant as an ‘erroneous belief’.Footnote 97 ‘The scientific botanist may tell the simple autochthones that they are wrong’, he observed. ‘I decline to do so, lest I lose my reputation for trusting, childlike faith’. His inclusion of Latin botanical names – likely from Cheeseman and Kirk – keyed to their native counterparts, alongside well-placed references to reputed naturalists, mark the culture Best wanted himself most closely affiliated to: that which had come to observe nature objectively, from the outside. As for Tūhoe peoples, Best extrapolated from what he considered to be their close relationship to the natural world to proclaim that the ‘forest is conservative, repressive, making not for culture or advancement … Some day a civilized tribe, from open lands, happens along, and hews down that forest. Then the [Urewera's inhabitants], human and arboreal, alike disappear, and the place knows them never again’.Footnote 98 In assuming the mantle of botanist, Best was both sharing in and shoring up natural science's self-declared authority over an obsolescent colonial nature, human and otherwise.

While Best may not have succeeded in passing himself off as a botanist with many readers, these nomenclatural exchanges nonetheless accomplished several things. First, they lent critical legitimacy to his ethnological observations by bringing them into rhetorical association with an acknowledged science. They also helped to generate a black-boxed abstraction of botanical authority for public consumption.Footnote 99 Finally, these exchanges appear to have played a constitutive role in how Best himself understood the relationship between indigenous and European ways of knowing. ‘Some of the shrubs, plants &c on the summit of M[ount] Pohatu are said by the natives to be quite local’, Best remarked in a letter to Cheeseman, ‘but Mr. Kirk seemed to know them all. The puakaito he informed me is a celmesia [Celmisia] … The kotare is also said to be quite local, which is probably incorrect’.Footnote 100 Despite his grounding in te reo Māori and close connection with numerous Ngāi Tūhoe individuals, Best lacked the botanical expertise to make an informed assessment of indigenous versus imperial ways of knowing, so he let Kirk, a non-Māori-speaking emissary of the natural sciences, make it for him. Indigenous phytonyms thus diffused into an increasingly hidebound settler public as ‘primitive survivals’ of a primordial, borderline subhuman way of relating to the natural world.

Previous commentators who perceived Māori plant knowledge in this way had been itinerant wayfarers, metropolitan specialists or South Islanders unversed in Aotearoa's languages and cultural norms. Settlers who came of age in later decades, on the other hand, as the examples of Smith and Best illustrate, could possess a sympathetic and relatively fine-grained acquaintance with indigenous botanical expertise, alongside a seemingly incongruous acquiescence to Māori extinction. Disciplinary specialization bolstered this colonial order of things by making botanical expertise the jurisdiction of specialists allied categorically to viewing plants in abstracted, delocalized terms, while European proficiency in indigenous botany became the near exclusive provenance of anthropologists with a vocational stake in a dehumanizing, primitivist outlook on indigenous knowledge. This partition was exacerbated by the two-way traffic in indigenous and European phytonyms, which enabled anthropologists like Smith and Best to trade on the epistemic authority of an established science, while it reinforced the standing of Cheeseman's and Kirk's chosen line of work. While indigenous plant names remained in colonial and global circulation, then, they did so as increasingly univalent signifiers of obsolescence and otherness. As boundary objects in transit between European and Māori cultural frameworks, in other words, indigenous phytonyms by 1900 did more to obscure than to illuminate this area of overlap.

Conclusion

Plant names play constituent roles in diverse knowledge pursuits and acquire various meanings within them. Native plant names in particular have sustained a further-reaching and more heterogeneous circulation than historians have by and large allowed. For nineteenth-century indigenous societies, they denoted critical means of material and cultural sustenance. Many European fieldworkers, for their part, recognized them as keys to a sophisticated and potentially lucrative storehouse of indigenous knowledge, and as signs of a naturalist at their vocational peak. Anthropologists, plant collectors deficient in native languages or herbarium-based botanists, on the other hand, were more likely to invest indigenous phytonyms with ethnological significance – as measures of racial and cognitive difference, or tools for speculating on the origins and migrations of plants and the peoples who used them. The history sketched here describes how one context of use came to predominate over others during the long nineteenth century.

I have traced this process to formative writings by Alexander von Humboldt, who drew an inverse correlation between plant diversity and cultural sophistication. European societies thereby compensated for an impoverished flora with their putatively richer languages and intellects. Reliable references, he argued – rendered stable, mobile and universal by instruments and agreed principles of classification – helped to narrow this gap between imagined and actual worlds, Linnaean plant names most prominently. As for indigenous nomenclatures, Humboldt proposed their use as philological finding aids in the quest for human and plant origins. This way of using indigenous phytonyms – as phonological data rather than as classifications in their own right – held disproportionate appeal for Europeans who lacked meaningful acquaintance with indigenous communities. John Crawfurd, Alphonse de Candolle and Berthold Seemann could thus discern evidence in vernacular phytonyms which bore out their own cultural prejudices.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, this perspective came into its own after the race-based hostilities of the 1860s, which encouraged figures like James Hector to view Māori ways of knowing in similarly ethnological terms. By the time Percy Smith and Elsdon Best took up these concerns, intensive settler study of Māori botany was the near-exclusive purview of commentators with a vested interest in promoting stereotypes of indigenous plant knowledge as anachronistic and unrefined, who lacked the natural-history expertise to pronounce otherwise. Smith's and Best's uncritical adoption of Linnaean plant names, both as an immutable reference point for mapping Indo-Pacific human migrations and as a yardstick against which to measure Māori ‘primitivity’, encouraged this disciplinary divide. Published references to Māori as experts and agents in the scientific knowledge of plants, meanwhile, became more infrequent in a discipline which confined its explorations increasingly to sparsely populated parts of the colony, or to university- and museum-based labs and herbaria. This is not to discount the critical roles that vernacular names and knowledge of flora continued to play in indigenous communities.Footnote 101 Nor is it to downplay the ongoing significance of commercially driven interest in indigenous plant knowledge.Footnote 102 But in turn-of-the-century Aotearoa New Zealand, the days of William Colenso, who fashioned an illustrious botanical reputation from acquaintance with the islands’ native flora and peoples conjointly, were – at least for the time being – finished. The late nineteenth-century hiving of competencies into a plant-centred botany on the one hand and a human-centred ethnology on the other only reinforced a growing disciplinary amnesia respecting the transcultural means by which imperial botany had achieved its earlier renown.