Curricular transformation has become imperative at most institutions globally in the last few years. Much of this discourse centres around the notion of decolonising knowledge (see Andreotti et al., Reference ANDREOTTI, DE OLIVEIRA, SHARON, CASH and DALLAS2015; Gordon, Reference GORDON2014; Kessi et al., Reference KESSI, MARKS and RAMUGONDO2020), which has taken centre stage in the debates in higher education in South Africa since the student movements #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall of 2015 and 2016, respectively. Although not a new debate, the ferocity of the debates and student actions were quite unparalleled in South Africa. In a newspaper article in Reference MAMDANI2011, Mahmood enquires, ‘What does it mean to teach humanities and social sciences in a location where the dominant intellectual paradigms are products not of Africa’s own experience but of a particular Western experience?’ Furthermore, he probes ‘And where, as a result, when these theories expand to other parts of the world, they do so mainly by submerging particular origins and specific concerns through describing these in the universal terms of objectivity and neutrality?’ These concerns have become central not only to the notion of decoloniality but also to the growing indigenous knowledge (IK) debates as these two concepts are closely aligned. While the IK debates are outside of the purview of this article, neither does it focus on the recent debates concerning decoloniality, spearheaded by Latin American academics, nor does it address the burgeoning field of curriculum studies. Instead, this is a reflective account of the curricular changes made by the African music section at the South African College of Music (SACM) at the University of Cape Town (UCT) since 2005; a process in which I have been integrally involved.

The main challenge in redesigning the curricula has been to move away from the dominant paradigm and rationale that govern the study of Western art music. The guiding question underlying our mission was, how do we conceive of a curriculum in African musics that is close and true to its musical practice? An underlying question was, how do we set about changing the knowledge both received and produced in this field? In my reflections on this process of curricular transformation, I draw on my colleagues’ and my experiential knowledge as well as students’ reflections on the changes. The resultant curricula, I suggest, can serve as an emergent model for an integrated approach to the teaching of African musics at African universities. I make a brief comparison with developments in African Studies in universities on the continent during the immediate postcolonial period and the radical debates around decolonising the academy with what was happening in African music studies. I illustrate how African music academics were more focused on music as sound than on investigating the postcolonial condition within their discipline through a cursory exploration of the articles published in an important journal and conference proceedings. Furthermore, I would like to posit that the scholarship we are involved with is rooted in Francis Nyamnjoh’s (Reference NYAMNJOH2019) notion of scholarship of conviviality grounded in incompleteness. He argues that convivial scholarship entails ‘conversing and collaborating across disciplines and organisations and integrating epistemologies informed by popular universes and ideas of reality’, founded upon incompleteness – ‘in persons, disciplines, and traditions of knowing and knowledge making’ (Nyamnjoh, Reference NYAMNJOH2019, p. 1).

Events at the University of Cape Town

On 9 March 2015, a student protest movement was initiated at UCT that challenged the institutional racism two decades after South Africa gained its democracy. #RhodesMustFall was a powerful student movement that questioned colonial and apartheid epistemologies, knowledge and curricula offered at a university that perceives itself to be at the forefront of knowledge production on the African continent yet critiqued as a bastion of White privilege. The statue of Cecil John Rhodes, featured in a prominent position on the campus, became the symbol of the anger and pain of students who felt excluded from the mainstream institutional culture. These students, often referred to as ‘the born frees’ as they were born after the first democratic elections in 1994, felt that there was not much to celebrate after two decades of democracy and that they hardly felt free. The protests contained an implicit critique of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) Government for the lack of delivery on their promises to the Black working class about their erstwhile rallying slogan ‘a better life for all’. Rhodes indeed fell a month later. On 9 April, the statue was removed but the protests grew into a national and international movement calling for the decolonization of education in South Africa, and indeed in other parts of the world, such as the US (Gupta & Stoolman, Reference GUPTA and STOOLMAN2022) and the UK (Lawrence & Hirsch, Reference LAWRENCE and HIRSCH2020; see also https://www.psy.ox.ac.uk/about-us/decolonising-our-curriculum), gaining much momentum in 2016.

This student protest movement made an impact on all departments and faculties and made me reflect, as head of the African music section, about our current offerings and the changes we have made over the years. At the time that we made these changes, we did not view them as anything as radical as ‘decolonizing the curricula’, or ‘removing colonial epistemologies from the curricula’, to quote the current jargon, but we were keen to develop an integrated approach to the study of African musics in the academy that was true to the musical practice, perhaps similar to how colleagues in Western classical music and jazz had developed their programmes. In the absence of models, my colleaguesFootnote 1 and I in the African music section created one ourselves and we drew on our varied experiences and expertise in various musical worlds to do so i.e., African, Western and South Indian musics. After the protracted and very challenging student protests since mid-September 2016, I felt less confident about our attempts to recover and validate knowledge systems and subjects of study deemed to be affirmingly African. The call for the decolonisation of university education by students has not spared any department or section from criticism, including the African music section.

At an imbizo (gathering) of students and staff at the SACM in August 2016, two African music students questioned the status of African music at the university. They raised a few pertinent issues around the study of African music at the university: the profile was very low, which they felt was obvious as witnessed in the limited number of African music concerts; they were made to feel inferior to students studying jazz and classical music, and they questioned why so few students were studying African music. At least one of these comments surprised me; I was quite unaware that students studying African music felt inferior to other students – they often are very confident performers, which does not suggest any feelings of deficiency. Although the questions the students raised may seem uncomplicated, the answers are rather more complex; rooted in our colonial and apartheid pasts, they are also very much part of our democratic present, in which the government (as well as funders) makes very few efforts regarding schooling and universities to seriously consider and change their organizational practices concerning the funding and study of the continent’s musics.Footnote 2

The study of African musics on the continent

This situation is not unique to South Africa: the place of African musics at universities on the continent is rather disconcerting. My sense – informed by visits to different campuses on the continent, and in view of the experiences of our students from various African universities – is that the study of African musics remains relegated to a marginal status in comparison to Western art music (or even jazz or popular music studies). This should not surprise us, as music departments, like universities on the continent, were either set up through colonial interests or later by Africans trained in the colonial system of education. African musicians and musicologists who excelled often continued their higher education in the United Kingdom at renowned institutions for the study of Western music, such as Trinity College or the Royal College of Music in London, and later in the United States. The impetus for university music departments across Africa was towards the study of Western art music, and Africa’s musics seemed to be appended as a curiosity or an interesting other, where students were given the opportunity to perform and dance ‘their’ indigenous musics.Footnote 3 Kidula (Reference KIDULA2006, p. 99) provides a trenchant critique on the hegemonic influence of Western epistemologies on the trajectory of African Musicology in the African academy. She suggests that ‘little critical assessment exists on how ethnomusicology and its cousins outside of Africa service the processes and intentions of music and its documentation for African continental scholars, educators and performers’. Unfortunately, the study of African musics at African universities has not changed all that much, except that the curiosity has been upgraded to a staple alongside the more established Western art music offerings. However, the systematic study of African musics at universities on the continent, which is the concern of this article, seems to be largely non-existent.

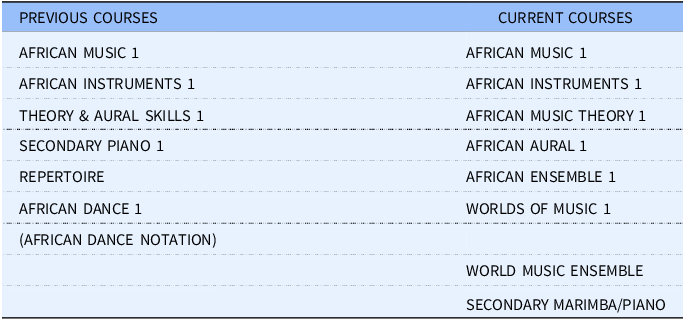

This situation existed in some form at UCT since the mid-1980s when ethnomusicology was introduced as a discipline along with the purchase of The Kirby Collection of Musical Instruments (the largest collection of southern African instruments in use before 1934, pre-dating urbanization). When I started teaching at the SACM in 2004, students studying ‘African music’ could choose from several streams: a four-year degree programme in Performance, Music Education, or Ethnomusicology, or enter a three-year Performance Diploma or even a four-year Music Education Diploma.Footnote 4 In all these programmes, students studied courses in Western music theory and aural for a few years. In the first year of the course named African Music, students were briefly exposed to various aspects, such as theory in the form of African notation systems and cultural history and it contained a small practical ensemble component. This was designed for students who were not specializing in African music and took the course as an elective for one or two years. Other courses studied in the African Music Diploma programme included African Instruments, Ethnomusicology,Footnote 5 Repertoire, Secondary Piano and African Dance. African Dance Notation was offered as an optional course for African music students. The aim was to offer students an integrated programme in African Music and Dance. Although the programme attracted numerous students, not many completed it while a few remained for far too long trying to complete their studies. Table 1 shows the list of courses for the first year of the African Diploma programme that was in existence until 2005.

Table 1. Curriculum of the first year African Music Diploma programme until 2005

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, we realised that there was a complete disjuncture between theory and practice. In particular, the Western music theory and aural courses kept many students repeating years at the SACM. We overhauled the curriculum by introducing Theory of African Music and African Aural, as well as World Music ensembles in place of African Dance due to constant timetable clashes. African dance has been incorporated into the African music ensemble courses and features prominently in our end-of-semester concerts. We introduced world music ensembles that had similar skills development as in African instruments, such as mallet percussion and drums. This boosted students’ techniques on these instruments as many of them did not possess the required skills when entering university.

This broad picture illuminates only some of the issues at hand. If one digs deeper into the structure of the course offerings, a lot more can be garnered in terms of how the content shaped (or not) the musicianship of African music students. This is borne out by the students’ feedback about courses, and by personal interaction with them. They were very concerned about what kind of professional future they could enjoy and felt somewhat ill-equipped as musicians or teachers. Although designed as an integrated programme of African Music and Dance, the rationale for courses seemed to follow that of the Western art music programme as I show in the next section.

Curricular transformation in the African Music section, SACM since 2005

In this section, I specify some of the changes we made over many years; the courses are listed comparatively in Table 2. The first change we made in the mid-2000s was to the course named African Music. We dislodged the practical, theoretical and historical aspects, guided by the idea that whoever wanted to learn African instruments should do so and learn the theory embedded within the practical as one learns to play instruments in various music cultures. The courses named African Music would emphasize the history, culture and literature of African musics across the continent. These courses concentrate on the subcontinent’s musics, both indigenous and popular, but also introduce students to the musics of North Africa and the islands of Africa.Footnote 6 Later we realised that, although there had been a minimal amount of African music theory in the first year of the previous course design as explained above, students gained some theoretical knowledge that they were no longer acquiring and the only formal theory they were being taught was Western classical music theory. By 2010, we had redesigned the curricula totally; we scrapped Western music theory and aural from the curricula, except in the Foundation year.Footnote 7 We also scrapped the Repertoire course, as it was clear that African music students learnt the musical repertoire through their practical application as well as through the theory and history courses without needing a ‘decontextualized’, stand-alone repertoire course. This notion of the separate study of repertoire clearly speaks to the Western classical music rationale and curriculum design. Now, students receive four periods a week of Theory of African Music (three years for the diploma programme and four years for the degree programme) and four periods a week of African Aural (for two years); both courses are much more closely aligned to their practical instruments and ensemble courses in African music. We introduced survey courses in our Worlds of Music courses in the first and second years, which included musics from the African diaspora as well as musics from various places in Asia and the Middle East. The third- and fourth-year courses are arranged around topics in African and World Musics, such as music and gender, music and race, musics from South Africa and improvised musics of the world with an emphasis on Africa and the diaspora. The African ensemble courses we introduced bring together various aspects of the African arts as an integrated whole, such as performing on instruments, dance, storytelling, visuals, and dramaturgy. Ethnomusicology as a named course was shifted to the postgraduate level where students are systematically introduced to the theoretical paradigms and methodology of the discipline. At this level, we also teach an African Musicology course which explores theoretical ideas and the historical representation of African music in the academy. The result of the changes was a vast improvement in undergraduate students’ progress through the diploma programme (for which most are registered) and their practical application. Their practical examination offerings were far more confident and creative, and students mostly moved through the programme within the required period. Students gain a much more holistic knowledge about African music and its practical application.

Table 2. Curriculum of the African Music Performance Diploma at UCT before the changes on the left and with the changes made after 2005 on the right. A non-music course, Language in the Performing Arts, has been added to prepare students academically

The World Music Ensemble courses are from Africa’s diaspora: Brazilian samba and Afro-Cuban ensembles, and students also took a year of South Indian music as we were fortunate to have a South Indian music specialist on the staff until 2016. A Pan-African popular music ensemble has replaced this ensemble. Briefly, the content of the African Music (history and culture) courses consists of surveys of indigenous, local and popular musics. We try to link topics, genres and regions to coincide with the instruments and ensembles in the practical courses, with an emphasis on musical bows and lamellophones. The content of the theory and aural courses, which are very closely aligned with each other and the practical instrument courses, cover key concepts (e.g., interlocking and polyrhythm), notation systems, scales and tuning systems located within specific regional musical practices as well as transcription methods. Our insistence on teaching African music theory is endorsed by the return to music theory and analysis in the field of ethnomusicology as exemplified by Tenzer’s (Reference TENZER2006) influential book, Analytical Studies in World Music and the online journal it spawned in 2011, Analytical Approaches to World Music. This return to earlier forms of methodologies, including Comparative Musicology, which was the mainstay of ethnomusicology before the 1960s, is somewhat intriguing, given the strong critiques of what was then regarded as positivist research. One of the discomforts scholars felt about the interpretive turn in ethnomusicology and critical musicology is that these sub-disciplines moved so far away from the music itself, although others feel that musical analysis has always held an important place in ethnomusicology such as the research done by Hugo Zemp, Simha Arom and Gerard Kubik (see Solis, Reference SOLIS2012).

In 2013, we forged the Ibuyambo Ensemble, a pan-African orchestra, responding to the challenges of teaching the craft of African musical performance in an urban institutional context. We saw the need for an African orchestra attached to a comprehensive undergraduate and postgraduate African Music Programme, to showcase a spectrum of diverse musical performance cultures. As a flagship demonstration of what is possible, a pan-African orchestra was thought to be an ideal vehicle for a wide spectrum of cultural exchange and communication, both among musicians and researchers on the African continent. Concurrently, we have attracted high-calibre musicians from southern Africa through the university’s Recognition of Prior Learning programme. Attracting these highly skilled but previously academically marginalised performing musicians into the Postgraduate Diploma programme has been immensely beneficial to our undergraduate students as they now have more examples of good musicianship at their doorstep. This initiative is transformative for both the musicians and the institution without detracting from academic quality.

A very recent addition to our curricula changes at the postgraduate level came through our involvement in the humanities research project titled ‘Re-centring AfroAsia: Musical and Human Migrations in the Pre-Colonial Period 700–1500AD’.Footnote 8 Decoloniality is at the heart of this project as it aims to research pre-existing forms of epistemologies and ontologies prior to coloniality. The research has the potential to unhinge our current Eurocentric knowledge and research about Africa. Due to the ephemeral nature of musical sound, this is a challenging research topic for music scholars, but it has proven to be rather exciting and wide-ranging and attracted eager young scholars with innovative topics for research as well as ideas around imaginative sonic recreations. To prepare our students for this challenging research, we introduced a postgraduate course called Indian Ocean Musics, in which we read very widely on African, Middle Eastern and Asian musics and cultures in the pre-colonial world. These readings introduced students to the histories of littoral East Africa and its interaction with the Indian Ocean World as well as the musical genres and cultural practices that have emerged historically.

The long, tedious process of conceptualising, proposing and securing the approval for these multiple changes from the university’s internal academic structures over many years could not have succeeded without debate with and the support of key colleagues in the department. The most challenging aspect of transforming the curricula was to convince some of our colleagues in curricular change meetings that the African Music programme needed to follow its own trajectory and develop new models of pedagogy and knowledge production. We needed to develop our own systematic study of African music without maintaining Eurocentric notions of scientific research and scholarship.

Student responses to the changes

In this section, I will explore students’ responses to the changes we made. I collated these from my interactions with students in class, a Facebook post as well as written responses from postgraduate students who had been through the programme either as undergraduate and/or postgraduate students.Footnote 9 While former generations of students, particularly those who went through these changes we made, showed much appreciation for the new orientation, the later generation of students were more critical. They were particularly critical of our historical approach, in which we insisted during the fourth year that they read some of the problematic articles that have shaped the canon of African Musicology. At the crest of the #MustFall wave, in a fourth-year course, I was accused of exposing students to the epistemological violence of the earlier texts, which was traumatic for (South) African students.Footnote 10 This Facebook post, which appeared in a discussion about the traumatic happenings at the institution during 2015, was typical of the accusations at the time:

White supremacist capitalist patriarchy at the South African College of Music makes it that: white literature dominates the curriculum, even in subjects like African Music; students of colour are expected to read of themselves referred to as n*, natives and k*Footnote 11 and that their expression of feeling violated and traumatised by this are made illegitimate by western notions of objective reasoning.

My rationale for the readings I assigned was not only that students understood the emergence of the discipline and the issues that preoccupied generations of scholars (yes, both Euro-American and androcentric) but that they also critique the canon and as emerging African music scholars think about developing an awareness of the issues that may be more interesting for African musicians themselves to investigate, rather than respond to what might be considered important academic interests. In this way, they would be better equipped to challenge the dominant Western knowledge paradigms on African musics. The student who wrote the Facebook post made similar critiques in my class of an A. M. Jones article I had given them to read, in which he set up a scenario of an ‘innocent soul of some African music-lover’ who plays, what might be considered a tedious, annoying rhythm, not regarded as ‘real’ music by Europeans (Jones, Reference JONES1949, p. 290). While the first paragraph is cringingly racist, the rest of the article systematically breaks down Eurocentric and racist notions of African music as tedious, monotonous or repetitive and extols the virtues of African musical aesthetics, particularly ‘the African’s’ enhanced rhythmic perception, to his colleagues at the time. It was clear that my radical student did not read beyond the first paragraph and made up her mind about the rest of the article. The students in the class pointed out to her the author’s intention with that first paragraph and quoted excerpts where the author refutes these Eurocentric notions and explains the intricacies of African music that would be completely missed by the Eurocentric mindset. In the end, she became quite overcome, saying it was the most radical article she had read during her entire four years at the institution! I sketch this scenario to show how fraught times of radical change can be for students as Jones is hardly radical although we cannot disregard his influence on disciplining African Musicology. His (and others before him) fascination with and focus on the complexities of African music/rhythm (see also Jones, Reference JONES1954) has generated years of attention to this aspect; in fact, African music has become synonymous with African rhythm (see Chernoff, Reference CHERNOFF1979; Kauffman, Reference KAUFFMAN1980; Locke, Reference LOCKE1982, Reference LOCKE1987; Reference LOCKE2009; Merriam, Reference MERRIAM1959; Waterman, Reference WATERMAN1948) until Agawu’s (Reference AGAWU1995) response to this ‘invention’ of African rhythm.

Recent responses from students have been more positive while some contain critiques. A Black female student, who completed a diploma in jazz but took several African music course electives, then completed an Honours degree in African Music in 2006 wrote:

These courses affirmed my own identity, heritage, and positionality as a black South African in the national narrative. They highlighted the legitimacy of cultural heritage and identities that were, at that time in South African history, not necessarily part of the mainstream or extolled. I am immensely grateful to the SACM for offering courses of this nature because they set a firm foundation for my career in music research and cultural policy studies.

From one of the few students who completed the undergraduate African Music Degree in 2015 and a master’s degree in 2018:

Altogether I had an amazing time during my undergraduate studies. The balance between practical, theoretical, and academic courses was excellent and was greatly enriching for me, as both a musician and ethnomusicologist. As someone who really appreciates different aspects of music–from playing together with friends in a percussion ensemble, to learning to embody 9 or 13 pulse cycles, to conversing about decoloniality in musics around the world–I feel I had a very well-rounded curriculum and set of core courses.

From three students who completed the African Music Diploma after courses introduced in 2010: first, a Black female now completing her PhD elsewhere:

I came as a musician with no scholarly music background. This programme helped me to learn and develop my theory and aural skills. I have gained a deeper insight into how to apply these to my music practice. The other courses helped me gain basic research skills, which I will apply as someone working within the music industry and continuing to study. Some courses were unnecessary, such as General Music Knowledge. Nothing was relevant to us; it was [about] western classical history. As a vocalist, it would have been great to have a vocal coach teaching traditional singing techniques. The other thing that did not work for me is that one person taught all practical instruments.

Second, a Black male now completing a master’s degree:

The programme has been beneficial in educating about different cultures and traditions across Sub-Saharan ethnic groups and their indigenous instrumentation and music. From various instrumental tunings such as the equi-heptatonic tuning found in Mozambique, to different scale modes including pentatonic scales found in East and West Africa, to the hexatonic scale of the bow music found in southern Africa. The academic courses of years 1, 2 and 3 interrelate effectively with the practical, theory and aural classes, making the African music programme a well-structured one.

Third, a Black female now completing a master’s degree:

As a student studying African music, the programme introduced me to various musical instruments from southern, West, and East Africa. The research programme taught me about diverse cultures’ social, musical and historical practices. Moreover, I obtained an intellectual grasp of the music I make, allowing me to communicate with musicians across the globe. Furthermore, I learned about alternative approaches to staging a performance, which broadened my perspective as a performer.

A White female jazz undergraduate student from 2006 to 2009, who returned in 2016 to complete the PhD, wrote:

I [had] lessons with Dizu Plaatjies on Xhosa bows and mbira which was a valuable part of my education. I took various academic subjects such as African Music and Worlds of Music. Although these subjects did not have a practical approach, they broadened my knowledge on many musics from around the world. After I graduated, the African music section developed significantly to include African Music and World Music Ensembles which I would have benefited from significantly. My one critique is that the African Music section takes a generalist approach, teaching students a wide range of instruments which does not serve students who want to specialise from the onset.

From a male Nigerian student who completed two years of the jazz degree in 2013 and then switched to African Music for his master’s and PhD:

My experience of studying African music at the SACM at UCT, was transformational as it shaped my worldview on music in Africa. Before studying at the SACM, I had never really considered how culturally diverse the continent was. The African Music courses made me think critically about the issues of representation, gender, cultural crossovers, indigenisation, syncretism, and comparing musical instruments to reconstruct history. If I had preferred anything done differently, it would be to have some more experience and discussions on real-life African contexts, so that the concepts taught in the books or articles could be better operationalised using African stories and examples.

From a White female student who completed the undergraduate classical music degree in 2007, then returned for the PhD in Ethnomusicology:

It was early on in my studies that I was required to take the Worlds of Music courses. I took the various African Music courses as well, all of which I found incredibly stimulating and ear-opening. These courses opened my understanding of musics around the world, music in its most abstract form, culture and society. The courses blended general knowledge, politics, ethics, other performance arts as well as the nuts and bolts of the musics themselves. I learned the beautiful challenges of academia and intellectualism in general. Theory and sound were blended seamlessly…I believe it is in those courses that I started to appreciate knowledge-production, research and writing. It is from those moments when music academia was modelled for me that I began to think that an academic career could be a possibility for me.

A male Colombian student who completed an Honours degree in 2017 wrote the following:

The vision that we have of the African continent in Latin America is very vague and too generic; we contemplate it as a lower continent after Europe, and North America, a vision that fortunately in me has ceased to exist. My time at the SACM at UCT in South Africa marked my life, [it] taught me a lot about people, about myself, I learned as a musician and as a person, it filled me with enthusiasm for the projects I have in the future. In addition, it presented me [with] a vision of music and the world that I didn’t know, it taught me respect and to maintain a critical look to the past, present, and future. The SACM gave me the academic tools I was looking for and much more.

A male Ghanaian student who completed the master’s degree in 2021, currently enrolled in the PhD, wrote:

In West Africa, parents continue to see how unnecessary and ‘evil’ it is for their children to go to a prominent school and end up studying African music. I was surprised and perplexed when this same African music got me into a master’s programme in South Africa, even on a scholarship. Students used to troop in for auditions to be accepted to study African Music. My impression of how the SACM treats African music has motivated me to engage deeply with African music academically.

From a White female student who switched from classical music to African music midway through her first year in 2013, then completed a master’s degree:

One of the most exciting things that happened was the start of the Re-Centring Afro-Asia Project. I registered for an MMus in Ethnomusicology and took several courses about precolonial Afro-Asia. These courses were a real mind-opener about the history of the world and music. Throughout the courses, I learned how knowledge about Africa and the Global South had been obscured in mainstream narratives about (musical) history. I also noticed that we played a really important role in redressing the idea that Africa’s musical history started with the first Western narratives about African music.

A White male undergraduate student in the classical degree programme from 2017 to 2020 who took several African and World Music course electives wrote this:

The courses got me to think more about my perceptions on music. I began to question the systems of power that had taught me that one music was superior to all others. However, these courses went beyond simply intellectual interest. I was exposed to and made sympathetic to the world around me. I began to grow in my political consciousness and ended up taking courses outside of the music department to learn more and gradually moved over to a musicology major, now specializing in South African youth music forms in postgraduate studies. I was forced to ask challenging questions about my positionality and privilege, which changed the way I lived.

While these are mostly glowing responses to the curricular changes, our approach is to remain vigilant, being acutely aware of the obsolescence of ideas in this fast-paced world, driven by information technology, social media exposure and cancel culture.

Institutionalisation of African music on the continent

Unlike the discipline of African Studies, African music has not institutionalised in any consistent manner since post-colonialism (see Zeleza, Reference ZELEZA2009 for a trenchant discussion on the institutionalisation of African Studies on the continent). The University of Ghana was probably the first university to offer African music studies in the 1960s as part of a unit of the Institute of African Studies (https://www.ug.edu.gh/music/about/brief_history accessed on 11 October 2019). At most universities in Africa, African music (or perhaps all music) is subsumed under the Department of Performing Arts, which is compatible with the notion of the African arts being much more integrated through music performance and not compartmentalised into unrelated art forms as in the West. Examples of such departments are at Makerere University: Department of Performing Arts and Film; University of Dar es Salaam: Department of Creative Arts; and Kenyatta University: School of Creative and Performing Arts, Film and Media Studies and so forth. However, there is generally a serious lack of emphasis on and specialisation in African music studies when it is part of a complex of performing arts studies. Again, unlike African Studies (also literature and history departments) in which ‘vigorous efforts were made to decolonise the disciplines, to strip them of their Eurocentric cognitive and civilizational conceits’, (Zeleza, Reference ZELEZA2009, p. 101) this kind of epistemic critique was still a distant future for most African music studies since much of the academic literature was still being written by Euro-American androcentric researchers as African music scholars were slowly emerging during the 1950s and 1960s. It is only since the late 1980s and 1990s that a more notable contingent of African music scholars has been publishing more consistently in music journals, but the flow of book publications has taken much longer to emerge.

Zeleza (Reference ZELEZA2009, p. 127) proffers the notion of a ‘deconstructionist tradition’ which collectively constitutes what he refers to as the ‘counterhegemonic insurgencies’ of ‘radical Marxist and feminist paradigms’ of the 1970s, which were joined by the ‘ambiguous posts’: poststructuralism, postmodernism and postcolonialism. He argues that African Studies is essentially “deconstructionist” as its intention was to undertake the undoing of the dominance of Western epistemologies in institutions on the continent. Since music studies often deal with sound as product rather than process, much of this deconstructionist tradition came to the discipline relatively later (see Agawu, Reference AGAWU1992; Reference AGAWU2003). In the next section, I explore the kinds of African music publications that emerged in the years between the 1950s and 1990s.

Developments in (South) Africa

I made a cursory investigation of African Music: Journal of International Library of African Music (ILAM, previously Journal of the South African Music Society), which was the premier journal of African music on the continent and in the diaspora since 1954 and published in South Africa. The emphasis on sonic aspects in the earlier articles is obvious in titles incorporating music of various cultural groups (Tiv, Yoruba, Akan, Bashi, Zulu), or of whole countries or regions (Gold Coast, Nigeria, Kenya, West Africa, Bantu Africa), also musical elements (pitch, harmony, rhythm, form), notation, transcription, music theory, organology, dance, the arts in Africa, lyrics/poetry, school music, music festivals, recording technology and much later, from 1972, trance possession and religious mysticism are included. These emphases show the lack of engagement with the emerging disciplines on the continent, such as African Studies, African History and African Literature in which far more robust discourses on postcolonial Africa and decolonisation were being deliberated. The first article to be published in African Music by an African music scholar was in the very first issue, by Nketia in Reference NKETIA1954 on ‘The Role of the Drummer in Akan Society’. Other African scholars trickled in since 1957, not digressing at all from the current fare on offer in the journal (e.g. ‘An African Orchestra’ by Osafo, Reference OSAFO1957). Current research, often by younger African scholars, is frequently taken up with correcting the wrongs of the earlier Eurocentric research (see Giminez & Maurice, Reference GIMINEZ and MAURICE2018; Kunnuji, Reference KUNNUJI2020), so in a sense, the emphasis is often still on sound product. While I point out these divergences between these African-centred disciplines, I am not necessarily critiquing this emphasis on sound as methodologically flawed; much of our content is music sound, which is integral to process and without which rituals, community or lifecycle events (processes accompanied by and dependent upon music) cannot occur. My objective is to give a broad overview of how African music has been and continues to be ‘disciplined’ in the academy. Nevertheless, the ‘deconstructionist tradition’ brings the critique of the unitary, classless, communal Africa into sharp focus and allows for more nuanced, historical and reflexive deliberations.

In South Africa, the study of African music in the academy was initiated during the 1980s, a time of serious anti-apartheid strife in society and of questioning the relevance of academic content of curricula at schools and universities. During this period, South African universities suffered under the academic and cultural boycott implemented by the United Nations. Hence, the music departments that implemented African music studies, such as the University of Cape Town (1984) and the University of KwaZulu Natal (introduced an African Music Ensemble in 1984 and degree programme in 1996), were also cut off from developments in the field on the rest of the continent. Consequently, studies were locally and regionally limited, which continue to shape the study of African musics in the country. Between 1980 and 2004, ILAM at Rhodes University organised and often hosted the Ethnomusicological Symposium for 18 years. The proceedings of these symposia, though not complete articles, give one a sense of the scholarship current at the time and are a veritable repository of African music research in southern Africa although again there were not many offerings in critical theory (see https://www.ru.ac.za/media/rhodesuniversity/content/ilam/documents/Symposium_Papers_contents_list.pdf. More universities in South Africa initiated African music courses or programmes in the 1990s and 2000s, such as the University of Fort Hare (1998) and Rhodes University (formal programme around 2000 although they offered African and world music ensembles for many years).

The field of music education was particularly active in the research and study of African musics as an alternative to Western offerings in the academy and at schools. This was premised on notions of diversity in the classroom and multiculturalism, a now much-critiqued paradigm. Elizabeth (Betsy) Oehrle in South Africa, much like Patricia Shehan Campbell in the US, was at the forefront of these new directions. The Talking Drum, a music periodical published annually since 1992 through Oehrle’s efforts, targeted schools and demanded academics to translate their research into information relevant to primary and high schools, for this often highly specialised information on music making in (southern) Africa to be more widely accessible. As is akin to such efforts, investigations remained centred on sound and movement as well as instruments, repertory, children’s songs, music education and dance as well as the offerings of different music departments at various South African universities.

Conclusion

The discourse on decoloniality has been emerging as fundamental to South(ern) African music studies as can be witnessed in recent conference presentations and published articles. In the last few years, the journal African Music has published three articles, which address various aspects of decoloniality. Carver (Reference CARVER2017) addresses the notion of decolonising the curriculum, particularly at the level of school music education, which has instituted only minimal changes regarding the music syllabuses taught at schools since democracy and its imperative for inclusivity. This is especially true for African musics with the ongoing lack of redressing the theoretical understanding of African musics. At this level, the study of Western music theory is still regarded as significant for the understanding of music in general, although African musics have unique intrinsic information that needs to be understood within its own parameters. Lucia’s (Reference LUCIA2017) article is an interesting reading of the choral composition of the Sotho composer Joshua Mohapeloa’s ‘Coronation Song’ and the changes it underwent during different political circumstances. She suggests that the subsequent reworking of the song in 1970 to a patriotic song after Lesotho gained independence incorporates decolonising musical aspects of US blues and the close harmonies of vocal jazz. Pooley’s (Reference POOLEY2018) article is by far the most critical of the canon of African musicology that emerged and was shaped within and by Western academic theoretical constructs and consequent imaginative limitations. His main contention is around the unitary notion of African music perpetuated in the canon since Hornbostel’s 1928 article and ‘taken to its logical conclusion in Agawu’s The African Imagination’ (Pooley, Reference POOLEY2018, p. 178). He argues that this ‘myth of a singular African music’ endorses the hegemony of continental musicology and its presumed superior modes of representation.

The intention of this article was to show how one music department set about dismantling or ‘decolonising hegemonic continental musicology’ (Pooley, Reference POOLEY2018, p.190) by systematically transforming the undergraduate curricula of the African music diploma and degree programmes. This did not happen overnight; it was a long, sustained effort of assessing the changes along with students’ progress and challenges. As the undergraduate programmes changed and our numbers at postgraduate level increased, we had to adjust the postgraduate Honours and Master’s programmes. We have reached a point where we are fairly satisfied with our offerings, but they remain up for scrutiny. The other challenge posed by Pooley is to develop southern theories to oppose the domination of the conceptual imaginary of the global north and its authoritative modes of representation. This is much more challenging than transforming curricula, however, we would like to believe that our transformed curricula provide our students with the necessary pragmatic and cognitive skills to bring a critical understanding of the discipline in both their performance and theoretical contributions. Our involvement with the Re-Centring AfroAsia research project has certainly revealed the richness of south-south interactions, knowledges and ideologies prior to colonisation. The increasing focus on the Indian Ocean WorldFootnote 12 is currently producing new knowledge that will dismantle Western hegemonic thought concerning the African continent and its musics that has emerged from the systematic academic focus on the Atlantic Ocean and its world dominated by Western epistemes. Similarly, our research focus on indigenous musics of southern Africa is yielding rich information translatable for the curricula of the various African music courses we teach. Our collaborations in these areas, both academic and socially engaged, are producing what Francis Nyamnjoh refers to as ‘conviviality in knowledge production’ (Reference NYAMNJOH2019, p.1), involving cross-disciplinary alliances and integrating indigenous oral/aural subjugated epistemologies. Consequently, our students are incorporating local, pre-colonial knowledges and practices into theses and performances, and, through creative methodologies gleaned contextually and through the process of research, are producing innovative research and musical creations inclusive of peripheral epistemes.