In any given year, approximately 20 % of children and adolescents globally have mental health difficulties, including major depressive disorder. Depression has been ranked as the second most common cause of death in adolescents, via suicide( Reference Patel, Flisher and Hetrick 1 , 2 ). As mental health problems often start in childhood or adolescence, they are strongly associated with other developmental and health conditions affecting quality of life, social, academic performance, personality disorders and substance abuse in adult life( Reference Kendall, Compton and Walkup 3 – Reference Berry, Growdon and Wurtman 6 ). There are limited evidence-based treatment regimens for this age group, including therapy, and a single licenced pharmacological treatment, fluoxetine( 7 ). Both treatments are only moderately effective, with up to 50 % of young people not responding to treatment or experiencing relapse and further episodes of depression( Reference Whittington, Kendall and Fonag 8 – Reference Goodyer, Dubicka and Wilkinson 10 ). An important area for development therefore is to prevent depression via public health interventions that can be delivered to an entire population of children and adolescents.

Over the past decade, several studies have suggested that diet could play an important role in treatment and prevention of depression. Two main approaches have been used to examine this relationship. A number of studies have investigated the impact of individual nutrients such as n-3 fatty acids( Reference Murakami, Miyake and Sasaki 11 , Reference Oddy, Hickling and Smith 12 ), vitamins such as B12 ( Reference Penninx, Guralnik and Ferrucci 13 ) and minerals such as Zn, Se and Fe( Reference McLoughlin and Hodge 14 – Reference Hawkes and Hornbostel 16 ). In addition, several intervention studies have examined the effect of supplements containing more than one nutrient (e.g. multivitamins, EPA and DHA) on mood( Reference Rogers, Appleton and Kessler 17 – Reference Silvers, Woolley and Hedderley 19 ). However, the idea of investigating individual nutrients to ascertain whether that single ingredient is responsible for improving mood is problematic. Mood regulation is influenced by a number of different neurochemical pathways (e.g. serotonin and dopamine), with each requiring several nutrients to supply the metabolites necessary for production of the individual neurotransmitters involved in regulation of mood( Reference Gandy, Madden and Holdsworth 20 ).

An alternative approach has been to explore the effects of whole diet and eating patterns on mood. In correlational epidemiological studies of adults, an ‘unhealthy’ and ‘Westernised’ diet was associated with an increased likelihood of mental disorders and psychiatric distress( Reference Jacka, Pasco and Mykletun 21 – Reference Sánchez-Villegas, Toledo and De Irala 24 ), whereas a ‘healthy’ or ‘good-quality’ diet was associated with better mental health( Reference Jacka, Pasco and Mykletun 21 , Reference Akbaraly, Brunner and Ferrie 25 – Reference Psaltopoulou, Sergentanis and Panagiotakos 28 ). However, several other factors such as socio-economic status (SES), household income and educational levels also influence dietary choice, and thus need to be included as potential confounders( Reference Goodman, Slap and Huang 29 , Reference Lemstra, Neudorf and D’Arcy 30 ).

Overall, studies with adults that have investigated the relationship between diet and mental health suggest that the relationship is complex and potentially bidirectional( Reference Murakami and Sasaki 31 ). Given the development of the brain during childhood and adolescence, and the emergence of depression during adolescence, the impact of diet on mental health may plausibly be greater during this period than later in life( Reference Kendall, Compton and Walkup 3 , Reference Kessler, Berglund and Demler 4 , Reference Giedd, Blumenthal and Jeffries 32 ). In addition, adolescents typically become increasingly independent and make more decisions about the type and amount of food they consume, including ‘junk’ and ‘fast’ foods( Reference Cutler, Flood and Hannan 33 ). Therefore, the relationship between diet and mental health in young people and children warrants specific attention.

In a recent review, twelve epidemiological studies that examined the association between diet and mental health in young people were identified and reviewed( Reference O’Neil, Quirk and Housdenm 34 ). It concluded that there was evidence for a significant relationship between an unhealthy diet and worsening mental health. Our review aims to advance knowledge in this field by (1) using a more sensitive measure of assessing methodological quality, and (2) assessing effect sizes across studies so that data can be compared on a single metric. Together, this will help describe the current status of the field, identify key methodological challenges facing researchers, synthesise and integrate existing research to highlight future research opportunities and implications for the development of dietary strategies to prevent childhood and adolescent depression.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted of social sciences, medical, health and psychiatric databases (i.e. PsycINFO, MEDLINE, PubMed, BIOSIS Cochrane Library and ScienceDirect). We identified relevant literature, published in the English language, from 1970 up to April 2016. Reference lists of related studies and reviews were also searched.

The search was carried out using the following combinations of key terms: internalising disorders or internali* or mental health or depression or depr* or depressive disorders or anxiety or anxi* or anxiety disorders or affective disorders or mood or mood disorders or well-being AND diet or nutrition or diet quality or dietary patterns AND youth or young people or adolescents or adol* or children or teen. As anxiety disorders commonly co-occur in children and adolescents with depression, with anxiety having an earlier age of onset, they were also included in the literature search( Reference Essau 35 – Reference Yorbik, Birmaher and Axelson 39 ). However, diet and its relationship with depressive disorders was the primary objective of this review.

Inclusion criteria

Studies eligible to be included in this review were as follows:

-

1. In English language.

-

2. Available as full text (including abstracts of meetings, etc.).

-

3. Included children and young people aged 18 years and below in the sample.

-

4. Study designs were case–control, cross-sectional, epidemiological cohort or experimental trials.

-

5. Examined the association between nutrition, dietary pattern, diet quality and internalising disorders (including low mood, depressive or anxiety symptoms and emotional problems).

-

6. Diet or nutritional intake measured via self-report (FFQ, diet records) or controlled weighed food records, observation or use of biological markers.

-

7. Diet quality measured by calculating scores from food frequency data or diet quality and diet patterns defined as overall habitual dietary intake.

-

8. Internalising disorders measured using self-report, doctor’s diagnosis, medical records, interview or depression/anxiety rating scales.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

1. Studies focused on disorders of eating or dietary restraint for weight-loss purposes.

-

2. Reported internalising disorder as a secondary problem to physical health problems (e.g. diabetes and heart disease).

-

3. Studies using only pregnant women as participants.

-

4. Animal studies.

-

5. Studies that focused on individual nutrients specifically.

-

6. Studies where all participants were over 18 years of age.

-

7. Mental health data limited to measures of behaviour or conduct (externalising problems).

The methodological quality of each study was assessed independently by S. K. and S. A. R., using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Disagreements were discussed with C. M. W. and a shared rating was given. Methodological criteria evaluated included the following: (a) bias in selection of participants, measurement or information with high risk of bias translating to a rating of poor quality and (b) study designs that could help determine a causal relationship between diet and mental health (Table 1).

Table 1 National Institutes of Health criteria list for assessing study quality

Results

This section describes in detail the process of literature selection, quality ratings of the studies, methodology used and also a summary of results of these studies.

Selection

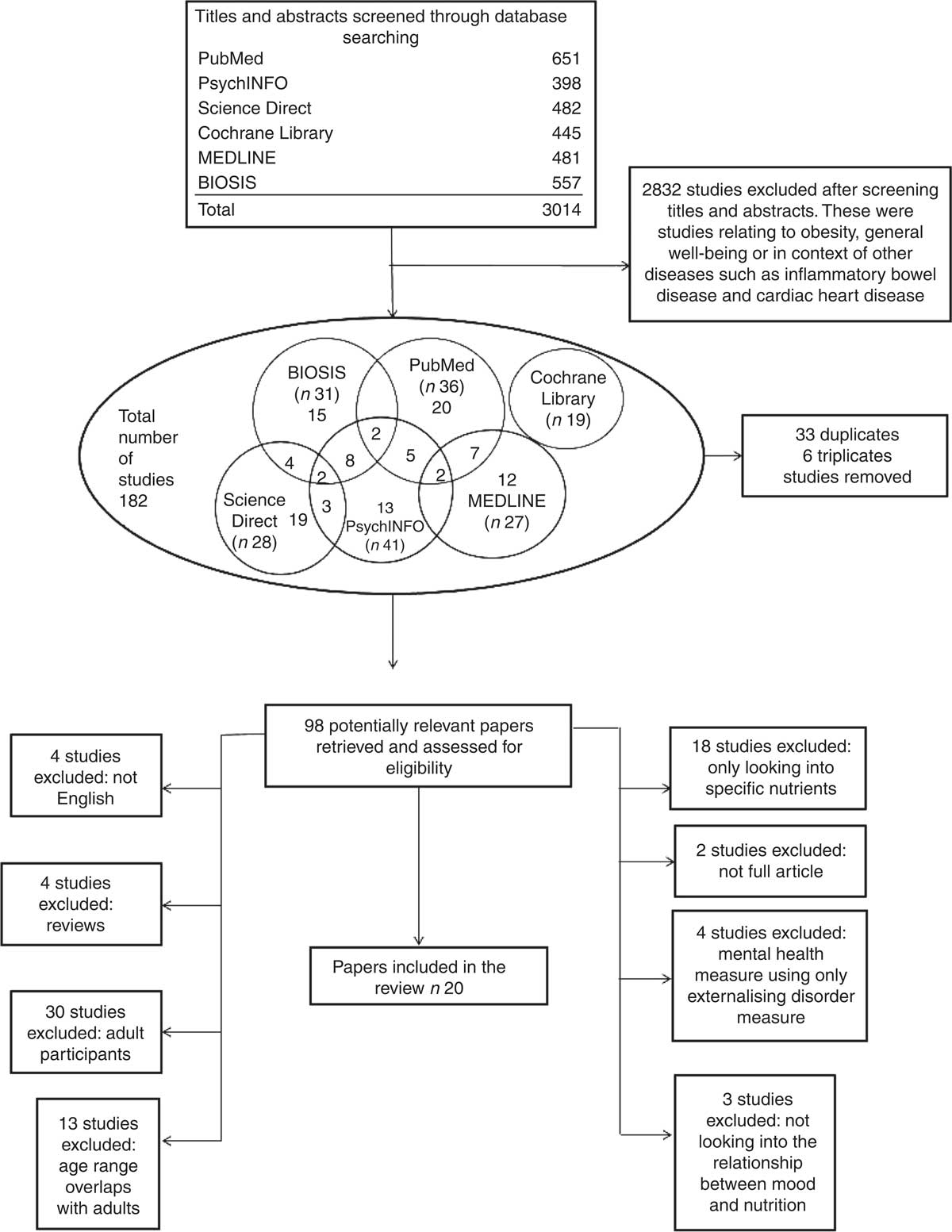

A total of 3014 studies were identified as a result of the initial search. Further screening identified ninety-eight studies relating specifically to nutrition and mood. Of these, seventy-eight were excluded, typically because participants were not in the appropriate age range, depression and/or anxiety was not measured, depression/anxiety were secondary to physical health problems or studies included calorie restraint or binge eating.

Complete details of screening, filtering and our selection process for the studies included in this review are shown in Fig. 1. In total, twenty studies that met inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified. Study populations were from USA, UK, Australia, Canada, Germany, Norway, Spain, Malaysia, Pakistan, Iran and China. Even though the traditional diets of non-western countries may differ, most of these studies investigated the consumption of junk or Westernised foods. Two studies, one from China and another from Norway, examined both Westernised and their traditional diets. Key features of the selected studies are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1 Showing the selection process of studies included in this review.

Table 2 Key features determining the quality ratings of the included studies (Mean values and standard deviations)

M, male; F, female; YAQ, Youth and Adolescent Questionnaire; SMFQ, Short Mood and Feeling Questionnaire; SES, socio-economic status; PA, physical activity; PedsQL, Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; PC, personal computer; DQI-I, Diet Quality Index-international; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; EuroQol, European Quality of life scale; BDI-II Beck Depression Inventory; CSIRO, Commonwealth Scientific and Research Organisation; CBCL, Child Behaviour Checklist; CES-DC, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children; DASS, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; EAS, Emotionality Activity and Sociability Questionnaire; DSRS, Depression Self-Rating Scale.

Data were extracted from seventeen cross-sectional studies and from three prospective cohort studies with follow-up periods ranging from 2 to 4 years. No experimental studies or clinical trials were identified. The total number of participants recruited across the twenty studies was 110 857, although two studies used participants from the same data set (The Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study; with n 1324 and n 1598, respectively)( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 ); 109 533 unique individual participants were recruited in total to these studies. There were 51 834 males and 49 588 females, although some authors did not clearly state the number of boys and girls in their studies( Reference Rao, Shah and Jawed 42 , Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 ). The age of participants ranged from 18 months to 18 years.

Overall quality

Using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, the quality of majority of studies was rated as ‘fair’ (n 16), with three studies classified as ‘good’( Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 – Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 ) and one rated as ‘poor’( Reference Rao, Shah and Jawed 42 ). The key methodological features of each study are outlined in Table 2. Common methodological weaknesses included inadequate measurement of the key variables (diet and mental health), which will be discussed in more detail below.

Measures of diet

Several different measures were used to measure dietary/nutritional intake across these studies. The most common and relatively reliable methods used were FFQ including Harvard Youth/Adolescent FFQ (YAQ FFQ; a widely used validated questionnaire) and Commonwealth Scientific & Industrial Research Organisation FFQ (semi-validated for use in adults). One particular study used 3-d food records, which are more reliable than FFQ( Reference Rubio-López, Morales-Suárez-Varela and Pico 46 ). In addition, a single study calculated absolute food consumption (to nearest gram) under controlled laboratory conditions( Reference Mooreville, Shomaker and Reina 47 ), which is considered one of the most reliable methods to measure dietary intake.

Diet quality was measured using questionnaires based on the FFQ in addition to National Healthy Eating Guidelines, Australian Guide to Healthy Eating, Amherst Health and Activity Survey of Child Habits, German Optimized Mixed Diet or Diet Quality Index-International scores. In each case, these consisted of components such as variety, adequacy, moderation and balance in the diet. None of these measures was validated. Other non-validated measures included questions on fruits, vegetables, sweets, snacks (including salty) and carbonated drinks consumption, in addition to regularity of breakfast consumption and skipping meals (Eating Behaviour Questionnaire). Simple questions with questionable validity such as ‘do you eat a healthy diet?’ were also used.

Most of the studies used measures that relied on child/adolescent self-report. A few studies used a parent or caregiver report of their children’s diet – this may affect the accuracy of the results because of social desirability factors or parents’ lack of knowledge of what the child might be consuming away from home. Overall dietary intake was not measured in a coherent way, and most tools used to measure nutritional intake or quality were not validated, particularly for the age range of the sample. In addition, there was a lack of consistency between the studies with regard to the items of food used to define healthy or unhealthy diet and whether diet quality or dietary patterns should be used to best define an individual’s dietary intake.

Measures of mood

A number of studies used measures of adolescent mental health that were well-established, validated and suitable for young people. The most common measures were the Child Behaviour Checklist( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Vollrath, Tonstad and Rothbart 48 ), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire( Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 , Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 – Reference Oellingrath, Svendsen and Hestetun 51 ), Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire( Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 , Reference Jacka, Kremer and Leslie 52 ) and Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children was also used by one study( Reference Rubio-López, Morales-Suárez-Varela and Pico 46 ). These were typically completed by parents of younger children or by adolescents themselves. Some studies measured depression only and others used measures that were composed of components measuring both depression and anxiety (‘internalising’ problems).

A wide range of other measures were also used. Some were generic measures of adolescent well-being that included elements of depression, for example, Paediatric Quality of Life, some were completed by professionals on the basis of an unstructured consultation, for example, International Classification of Disease (ICD-9/10), and others were specific to depression but not designed for use by children and adolescents, for example, the Beck Depression Inventory (II) and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21). Additional ad hoc items such as ‘during the past 12 months, how often have you been so worried about something that you could not sleep at night?’, ‘During the past 12 months, did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide?’ and questions on frequency of feeling depressed were also used but are of doubtful validity.

Study design

Most research studies used designs that were cross-sectional. This was a relatively weak design because it was not able to determine the direction of the relationship between diet and mood. Longitudinal studies were uncommon. Socio-economic variables that are highly correlated with mood in children and young people and that are related to diet, such as SES, income and parents’ educational level, were not measured consistently and were neither measured nor controlled by some studies( Reference Mooreville, Shomaker and Reina 47 , Reference Vollrath, Tonstad and Rothbart 48 , Reference Brooks, Harris and Thrall 53 – Reference Tajik, Latiffah and Awang 55 ). The most common confounding variables that were controlled were age and sex of participants. Some important variables including medical conditions such as hypothyroidism, diabetes and food allergies, which may be correlated to mood or food choices, were not considered by any study.

Effect sizes

The association between diet and mental health was reported in a number of different ways. The most common method of evaluating the relationship between diet and mental health was to calculate the increased risk of depression given different types of diet. Other methods of analysis were univariate associations between the variables, multivariable linear regression and negative binomial regression with results reported as incidence rate ratio.

To allow the results of different studies to be compared on the same metric, we calculated effect sizes for all key variables where data were provided using the Practical Meta-Analysis Effect Size Calculator( Reference Lipse and Wilson 56 ). Two studies did not report data in a way that made this possible( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ).

Relationship between nutrition and mood

The main results of the twenty studies, including the effect sizes, are shown in Table 3. Owing to the heterogeneity of the constructs, measurements and definitions of both internalising (depression and anxiety) symptoms and dietary intake, for example, quality, patterns, food groups and eating behaviours, the key results were grouped and described into the following broad categories.

Table 3 Key results (Interval risk ratios (IRR), b values and 95 % confidence intervals)

SDQ, Strengths and Difficulty Questionnaire; SMFQ, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire.

* Significant results.

Healthy diet

Overall healthy diet

A ‘healthy’ diet was broadly defined as positive eating behaviours and consumption of fruits and vegetables, health-promoting behaviours and avoiding ‘unhealthy’ food. However, there were inconsistencies regarding food items such as grains and legumes being part of a healthy diet. The relationships between a healthy diet or a healthy diet pattern and depression were investigated by eight studies( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Jacka, Kremer and Berk 44 – Reference Rubio-López, Morales-Suárez-Varela and Pico 46 , Reference Jacka, Kremer and Leslie 52 – Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 , Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 ). Five studies reported a significant association between a healthy diet and lower depression with effect sizes ranging from small to medium (d=0·5( Reference Jacka, Kremer and Leslie 52 )). There were a few exceptions( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 , Reference Rubio-López, Morales-Suárez-Varela and Pico 46 ), where there was a weak evidence for an association between a healthy diet pattern and internalising symptoms. One study( Reference Brooks, Harris and Thrall 53 ) reported that the association between ‘healthy’ diet and mood was significant only for females (d=0·14). One research group explored the relationship between mental health and diet in a longitudinal design at two time points( Reference Jacka, Kremer and Berk 44 , Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 ). Jacka et al.( Reference Jacka, Kremer and Berk 44 ) found that a healthy diet predicted depression 2 years later (d=0·43) but that depression at baseline did not predict healthy diet consumption (d=0·02) 2 years later. In contrast, Jacka et al.( Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 ) found no association between a healthy diet and mental health 3 years later (d=0·11).

Fruits and vegetables

There were conflicting results regarding fruit and vegetable intakes, and their association with mood. The studies that explored this association( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 , Reference Renzaho, Kumanyika and Tucker 50 , Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 , Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ) all measured fruits and vegetables separately, except for two studies( Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 , Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ), who grouped these variables into a single category. Only one study( Reference Renzaho, Kumanyika and Tucker 50 ) investigated whether mental health was associated with fruit and vegetable consumption. The majority of studies found no significant association between consumption of fruits and vegetables and mood. However, one study reported that compared with healthy individuals, individuals with emotional problems consumed significantly less fruit (in both males and females, average d=0·185) and vegetables (only in females, d=0·1)( Reference Renzaho, Kumanyika and Tucker 50 ). Another study reported that consumption of fruits and leafy green vegetables (only) was significantly associated with lower odds of internalising symptoms( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 ). Other vegetables such as cruciferous and yellow/red vegetables were not associated with internalising problems( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 ).

Other food categories considered ‘healthy’

-

1. Cereal and grains: two studies( Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 ) examined the effect of cereal consumption, whereas one( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 ) examined the effect of whole and refined ‘grains’ on mood. There was no evidence that cereals or grains were significantly associated with depression.

-

2. Dairy products: all three studies( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 ) reported no significant association between dairy products and depression.

-

3. Fish: four studies( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 , Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ) explored fish intake and its association with depression. However, only one( Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ) study reported higher fish consumption to be significantly associated with decreased odds of developing mental health difficulties.

Unhealthy diet

Overall unhealthy diet

Six studies investigated the relationship between unhealthy diet and mental health( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Rao, Shah and Jawed 42 , Reference Jacka, Kremer and Berk 44 , Reference Jacka, Kremer and Leslie 52 , Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 ). An ‘unhealthy’ diet was broadly defined as one comprised of fast foods or take-aways, foods containing high fat and sugar levels, confectionery, sweetened beverages, snacking, Western dietary patterns and unhealthy food preferences. Typically, ‘unhealthy’ diets were reflected in a continuous score with higher levels indicating an unhealthier diet. Each of the studies reported a significant cross-sectional association between unhealthy diets and depression, with small-to-moderate effect sizes (d=0·1 to 0·39). Jacka et al.( Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 ) explored the link between mental health and an unhealthy diet in a longitudinal design. They found that unhealthy (d=0·26) diet at baseline significantly predicted the occurrence of depression 2 years later but did not predict depression at 3 years (d=0·097)( Reference Mooreville, Shomaker and Reina 47 ). They also reported no association between depression at baseline and unhealthy diet consumption over time (d=0·06)( Reference Jacka, Kremer and Berk 44 ).

Fast food/take away/eating away from home/junk food

Seven studies investigated junk food or fast food consumption and mental health in adolescents( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 , Reference Rubio-López, Morales-Suárez-Varela and Pico 46 , Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 , Reference Tajik, Latiffah and Awang 55 , Reference Zahedi, Kelishadi and Heshmat 59 ). Food items within this category consisted of Western food items or processed foods such as hamburgers, pizzas, meat pies, savoury pastries, fried food, hot chips, coated poultry and soft drinks. The food items included were more or less similar for different countries and cultures. Four studies( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Tajik, Latiffah and Awang 55 , Reference Zahedi, Kelishadi and Heshmat 59 ) reported an association between high take-away/fast food consumption and increased odds of mental health problems. Overall, the effect sizes of these studies were small, with the exception of one study( Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 ) that included confectionery and snacking as a part of junk/fast food consumption, and therefore reported a large effect size of junk food on mental health (Table 3). One study( Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 ) used a longitudinal design, with dietary consumption measured by a parental report at 4·5 years and parent-reported mental health problems at the age of 7 years. Consumption of junk food at 4·5 years did not predict emotional problems at 7 years.

Snacking

Snacking was defined as the consumption of the following food items between meals: preserved fruits, confectionery, crisps, ready-to-eat savouries, salty snacks, carbonated beverages, etc. Five studies examined the relationship between snacking and depression( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Rubio-López, Morales-Suárez-Varela and Pico 46 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 , Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 , Reference Zahedi, Kelishadi and Heshmat 59 ). Only two studies( Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 , Reference Zahedi, Kelishadi and Heshmat 59 ) reported a significant association between snacking and depression, with small effect sizes (d=0·05 and 0·12).

Confectionery/sweets

This category is divided into sweet foods such as confectionery, cakes, biscuits and sweet drinks such as soft drinks and sweet beverages. Four studies examined the relationship between confectionery or sweet foods and depression in a cross-sectional design( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 , Reference Mooreville, Shomaker and Reina 47 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 ), of which three( Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 , Reference Mooreville, Shomaker and Reina 47 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 ) found a significant cross-sectional association. In a longitudinal study, there was no significant association between sugar consumption and mental health after 3·5 years( Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 ). One study( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 ) found no association between consumption of baked goods and depression, but reported a significant association between confectionery consumption and increased odds of depression; the effect size was, however, very small (d=0·04). Three studies( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 , Reference Zahedi, Kelishadi and Heshmat 59 ) also investigated the effects of sweet drinks on mood. Daily consumption of sweet drinks was significantly associated with increased depressive symptoms in all three studies; the effect sizes of these studies were small (d=0·09–0·25), and in one study( Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 ) the effect was significant only in males (d=0·25). One study( Reference Vollrath, Tonstad and Rothbart 48 ) explored the association between mental health on consumptions of sweet foods and drinks, and reported that individuals with poorer mental health were more likely to consume sweet foods and drinks.

Meat

The association between meat consumption and mental health was investigated in four studies( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 , Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 ). Three( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 , Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby 41 , Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 ) investigated the effects of red meat and meat products, and one( Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 ) study explored the effect of ‘animal’ dietary pattern, consisting of processed meat and other meats on mental health. Only one of these four studies( Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini 40 ) reported that high meat consumption was significantly associated with poorer mental health.

Other food categories considered unhealthy

-

1. Fats: three studies investigated fat intake, one explored intake of fats and oils( Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 ) and two( Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 , Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ) reported total percentage fat intake. These three studies did not find a signification association between fat consumption and depression.

-

2. Caffeine: only one study examined the relationship between caffeine and mood and found that caffeine was significantly associated with depression (average d=0·37)( Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 ).

Overall diet quality

In addition to ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ diet being investigated separately, the association between overall diet quality and depression has also been explored( Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 , Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 , Reference McMartin, Willows and Colman 60 ). Two studies( Reference Kohlboeck, Sausenthaler and Standl 49 , Reference McMartin, Willows and Colman 60 ) reported an association between higher diet quality scores and depression with a small effect size (d=0·025 and 0·03, respectively). One study reported no significant association between depression and overall diet quality; however, they did report that greater variety and adequacy of the diet was significantly associated with a lower level of emotional problems (unable to calculate effect size)( Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ).

Eating behaviours

The relationship between depression and ‘eating behaviours’ such as having breakfast, lunch, dinner and skipping meals was explored in two studies( Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 , Reference Tajik, Latiffah and Awang 55 ). Both reported significant associations between having breakfast and lower depressive symptoms (d=0·31( Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 ), d=0·03( Reference Tajik, Latiffah and Awang 55 )). However, there were conflicting results regarding lunch and dinner consumption. One study showed an association between higher depression symptoms and individuals who skipped dinner (average d=0·28) or lunch (average d=0·34)( Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 ). The second study found no significant association between depressive symptoms and having lunch (d=0·03) or dinner (d=0·048)( Reference Tajik, Latiffah and Awang 55 ).

Overall dietary intake

A recent study investigated the association between self-reported depressive symptoms and twenty-nine different nutrients (including macronutrients, micronutrients and minerals)( Reference Rubio-López, Morales-Suárez-Varela and Pico 46 ). Intakes of protein, carbohydrates, pantothenic acid, biotin, vitamin B12, vitamin E, Zn, Mn, Co, Al and Br were significantly lower in children with depressive symptoms. However, consumption of thiamin and vitamin K was high in children with depressive symptoms when compared with non-symptomatic peers. However, the effect sizes for the significant results were small ranging from d=0·18 to 0·21, with the exception of biotin (d=0·99). The list of all the nutrients and their effect sizes is reported in Table 3.

In addition, two further studies have investigated a few specific nutrients in addition to exploring overall ‘diet’. Fulkerson et al.( Reference Fulkerson, Sherwood and Perry 54 ) investigated Ca, Fe, sucrose, vitamin D, folate, vitamin B6 and B12 intakes, whereas McMartin et al.( Reference McMartin, Kuhle and Colman 57 ) investigated the intake of n-3 fatty acid and the ratio between n-3:n-6. Neither study found an association between consumption of any of these nutrients and mental health problems.

Diet and anxiety

Three studies( Reference Rao, Shah and Jawed 42 , Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 , Reference Zahedi, Kelishadi and Heshmat 59 ) explored the association between diet and anxiety alone, with one( Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 ) also exploring the relationship between co-morbid depression and anxiety. There was a significant association between anxiety and three or more unhealthy behaviours such as consumption of fast food and sweet beverages( Reference Rao, Shah and Jawed 42 ). Another study( Reference Zahedi, Kelishadi and Heshmat 59 ) reported that consumption of sweets, sweet beverages, fast food and salty snacks was associated with increased odds of anxiety. However, the effect sizes of both these studies were small (d=0·21 and d=0·21; Table 3). Higher consumptions of ‘animal’ food types and ‘snacking’ dietary patterns were associated with anxiety and co-morbid depression( Reference Weng, Hao and Qian 58 ). A traditional dietary pattern, consisting of typically healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables, oatmeal and wholegrain, was negatively associated with coexisting depression and anxiety (d=0·04) but not with anxiety alone.

Discussion

This systematic literature review identified and evaluated studies examining the relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents. At present, the first-line treatment for depression is psychological therapy, and a single antidepressant that acts through dopaminergic, serotonergic and monoaminergic mechanisms. These, however, fail to decrease the burden of depression because of people’s lack of response to these medications, especially the younger population( Reference Blier 61 ). This suggests that there may be an alternative mechanism through which depression can be targeted. Any possible method of preventing the development of depression symptoms or reducing existing symptoms has great potential as a public health intervention. In addition to potential nutritional interventions, other possible therapies that are being investigated include the use of other psychoactive compounds such as agomelatine, which synchronises circadian rhythms, targeting inflammation and gut microbes( Reference Dale, Bang-Andersen and Sánchez 62 – Reference Luna and Foster 65 ). Review of these other potential treatments is beyond the scope of this review.

Despite the importance of the topic, we found relatively few studies that examined diet and mental health in adolescents, especially when compared with the large number of studies with adult participants.

Our review highlights several important issues, both methodological and substantive. From a methodological perspective, there are significant problems in the design and conduct of epidemiological studies. Although only twenty studies were identified, a range of different ways of defining and conceptualising diet quality was used that could not be easily compared or integrated. Even well-established measures of diet quality relied on retrospective self-report of food consumption, which is of dubious reliability and validity. The more intrusive but reliable use of daily food diaries was rarely reported. The measurement of depression and associated mental health difficulties was somewhat more satisfactory in that some well-standardised and validated measures with good psychometric qualities were used.

Of more concern, however, is the related problem of the study design; all the studies identified in this review were correlational. Only three included a longitudinal element, and thus most could not help determine the direction of the causal relationship between diet and mood( Reference Wiles, Northstone and Emmett 43 – Reference Jacka, Rothon and Taylor 45 ). Intervention studies, using an overall diet strategy, are the only robust way to establish causality; if these are impractical or impossible to conduct, then it is essential to conduct careful longitudinal studies with adequate methods of measuring key constructs of diet and mood. Further adding to the difficulty in understanding any causal relationship between diet and mental health is that both diet and mood are influenced by many other factors including SES, culture and age( Reference Cutler, Flood and Hannan 33 , Reference Wardle and Steptoe 66 – Reference Gilman, Kawachi and Fitzmaurice 69 ). A few studies attempted to control the impact of important confounds, and thus any observed relationships between diet and mental health must be interpreted cautiously. It is entirely plausible that low mood and poor diet are both caused by the same third variable, low SES or social exclusion, both of which would act to restrict access to a varied healthy diet and to increase adverse life and other environmental causes of poor mental health.

These methodological problems made it difficult to integrate the studies and to make inferences regarding the association between mood and dietary pattern. Most studies included multiple measures of ‘diet’ quality or content and included multiple significant testing, thus increasing the likelihood of types I and II errors. To impose some consistency on the results of multiple statistical tests using different measures of diet and mental health, we calculated the effect sizes for each study. Given the caveats outlined above relating to methodological and conceptual problems, there was a general tendency to report small associations between diet and mental health, with ‘unhealthy’ diet associated with increased odds of mental health difficulties and ‘healthy’ diet having the opposite effect. Similar conclusions were drawn in the studies investigating whether a healthy or unhealthy diet is associated with depression in adults( Reference Jacka, Pasco and Mykletun 21 – Reference Psaltopoulou, Sergentanis and Panagiotakos 28 ). The conclusion that there is an association between unhealthy dietary pattern and worsening of mental health observed in this review was consistent with the recent review( Reference O’Neil, Quirk and Housdenm 34 ). However, the consistent association between unhealthy dietary pattern and worsening of mental health found in this review contradicted the observations of the previous review( Reference O’Neil, Quirk and Housdenm 34 ).

No inferences could be made about the associations between fast food, vegetables and fruits and mental health. Therefore, because causality cannot be determined, it is important to note that there is a plausible alternative causal pathway, whereby low mood leads to increased consumption of unhealthy ‘junk’ food – for example, chocolate and decreased consumption of ‘healthy’ foods. These conflicting and heterogeneous findings regarding the association between fruit, vegetables, fast food and mental health are similar to those found in adult studies. Indeed, a recent review of adult literature also identified similar problems regarding method quality and the inconsistencies between the constructs( Reference Quirk, Williams and O’Neil 70 ).

Given the inherent limitations of cross-sectional research designs and the demands of large community intervention studies, another tactic may be to focus on observational and intervention studies with ‘at-risk’ or clinical populations. This could involve comparisons of nutritional intake between healthy adolescents and those with anxiety and depressive disorders. However, in order to make confident causal statements about the effects of diet on mental health, intervention studies are required, and these can be best informed by theory about mechanisms and better designed correlational studies.

Overcoming the methodological problems discussed in this review will require greater collaboration and communication between researchers. This will help establish clearer and more consistent definitions and constructs, and more shared use of reliable and valid instruments that can be used consistently across cultures, communities and cohorts.

Conclusion

Research regarding dietary pattern or diet quality and its association with mental health in children and adolescents is at an early stage. This review highlighted some conceptual and methodological problems that, if not addressed, will impede future research and public health interventions. It is therefore essential to make sure that further methodological problems are minimised to at least establish the strength of any association between diet and mental health.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

We are most grateful to Lynne Bell for her statistical guidance.

Authors’ responsibilities were as follows: S. K. had the primary responsibility for writing the manuscript. S. K. and S. R. contributed to the literature search and analysis of the data published. S. R. and C. W. reviewed and approved the manuscript. All authors contributed to the editing and revisions of the article.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest arising from the conclusions of this work.