The growing demand to substitute fish meal in aqua feed has resulted in the need to search for alternative less-expensive and protein-rich sources( Reference Brinker and Friedrich 1 ). Soyabean meal (SBM) is one of the most promising plant protein sources as a fish meal substitute in fish feeding( Reference Silva-Carrillo, Hernández and Hardy 2 ). However, its use is also limited because of the occurrence of the antinutritional factors( Reference Zhao, Qin and Sun 3 ). Glycinin, the main storage protein in soyabean, has been identified as a major antinutritional factor in soyabean( Reference Wang, Qin and Sun 4 ). Studies have shown that glycinin could reduce weight gain in piglets( Reference Zhao, Qin and Sun 5 ). Our previous studies demonstrated that poor growth performance is always attributed to a reduction in the digestive and absorptive ability, which is partially related to the impaired intestinal integrity of fish( Reference Jiang, Wu and Kuang 6 , Reference Jiang, Feng and Liu 7 ). Limited studies have observed that glycinin could cause intestinal epithelium damage in piglets( Reference Zhao, Qin and Sun 5 ). However, until now, the underlying mechanisms by which glycinin caused damage to the intestine epithelium in animals have been largely unknown. Nevertheless, this topic is very important for understanding and resolving the problems of using high doses of SBM.

The intestinal structural integrity relies on the integrity of the intestinal physical barrier, which comprises intestinal epithelial cells( Reference Wen, Feng and Jiang 8 ). Our previous studies observed that the intestinal epithelial cell structure of fish is very sensitive to oxidative damage( Reference Jiang, Wu and Kuang 6 , Reference Chen, Zhou and Feng 9 ). However, whether glycinin-induced intestinal injuries are associated with oxidative damage has not yet been studied in animals. It was indicated that glycinin, as a major allergen in soyabean, could cause inflammatory disorders in mice( Reference Xu, Zhou and Wang 10 ). Intestinal inflammation always invokes subsequent peroxidative damage because of the excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in rats( Reference Turan and Mahmood 11 ). In addition, oxidative damage occurs, in part, when antioxidant enzyme gene transcriptions is not sufficient to produce enough enzymes to combat the excessive ROS in organisms( Reference Kohen and Nyska 12 , Reference Jiang, Liu and Jiang 13 ). The gene transcription of antioxidant enzymes is typically regulated by Nrf2 (NF-E2-related factor 2) signalling pathways in fish( Reference Kobayashi, Kang and Watai 14 ). Our previous study observed that excessive ROS could destroy the antioxidant system and disturb the Nrf2 signalling and thus cause oxidative damage to juvenile Jian carp (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian)( Reference Jiang, Liu and Jiang 13 ). That information indicated that glycinin-induced intestinal damage in animals might be related to the disturbance of the antioxidant system and the induction of oxidative damage, which needs to be investigated.

In addition to the integrity of the intestinal cells, the intestinal structural integrity also relies on the integrity of the tight junction (TJ) complex between epithelial cells, such as occludins and claudins in fish( Reference Wen, Feng and Jiang 8 ). Until now, to the best of our knowledge, only one study had investigated the effects of glycinin on the TJ in animals/cells, finding that glycinin reduced the expression of occludin and claudin-3 in in vitro porcine intestinal epithelial cell lines (IPEC-12)( Reference Zhao, Liu and Han 15 ). Although those observations indicated that glycinin could influence the intestinal TJ in animal cells, several questions need to be resolved. For instance, (1) in vitro cell lines cannot fully reflect the physiological response in vivo in live animals( Reference Unger, Krump-Konvalinkova and Peters 16 ), and (2) TJ genes are largely different between fish and terrestrial animals. In the teleost fish Fugu rubripes, the claudin superfamily consists of fifty-six claudin genes, whereas in humans it comprises only nineteen claudin genes( Reference Loh, Christoffels and Brenner 17 ). Thus, studies of the effects of glycinin on the TJ in the intestines of fish are quite necessary.

TJ proteins are regulated by cytokines in mammals( Reference Capaldo and Nusrat 18 ). However, little attention has been given to the potential effects of dietary glycinin on the cytokines in fish. In mice, the administration of glycinin could promote the secretion of inflammatory cytokines in the intestinal epithelial cells( Reference Xu, Zhou and Wang 10 ). There exist large differences in the digestive tracts of terrestrial and aquatic animals. Some fish species, such as carp, do not have stomachs, whereas terrestrial animals have at least one stomach( Reference Feng, Zhang and Wei 19 ). Thus, whether dietary glycinin has effects on cytokines, and thus affects the TJ in the intestines of fish, needs to be investigated.

Apoptosis is essential for the removal of neutrophils from inflamed tissues and the timely resolution of inflammation. However, excessive apoptosis could destroy the structural integrity of fish intestines( Reference Hoyle, Shaw and Handy 20 ). In mammals, cell apoptosis could be inhibited by target of rapamycin (TOR) signalling( Reference Zeng, Wang and Shi 21 ). However, information about the effects of glycinin on either cell apoptosis or on TOR signalling in fish is scarce. In piglets, glycinin was reported to induce the duodenum apoptosis, whereas it did not induce apoptosis in the mid-jejunum and ileum. Fish intestines are generally divided into three intestinal segments: the proximal intestine (PI), the mid intestine (MI) and the distal intestine (DI)( Reference Wen, Feng and Jiang 8 ). Thus, it is very important to investigate the effects of glycinin on the TJ, cytokines and apoptosis in different intestinal segments (PI, MI and DI) of fish.

Glutamine (Gln), a conditionally essential amino acid, appears to be a key nutrient for the gut in mammals( Reference Satoh, Tsujikawa and Fujiyama 22 ). Our previous study has demonstrated that dietary Gln supplementation increased the intestinal weight and alkaline phosphatase (AKP) activity, and thus improved fish intestinal structure and function in juvenile Jian carp( Reference Lin and Zhou 23 ). Further study by our laboratory demonstrated that it could protect fish intestines against another soyabean anti-nutrient factor – β-conglycinin-induced oxidative damage( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ). Accordingly, we set up a treatment that administered Gln combined with glycinin to investigate whether Gln could protect fish against glycinin toxicity.

The present study evaluated the hypothesis that dietary glycinin exposure might decrease the growth of fish through injury of intestinal health caused by oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis, which contributes to the damaged structural integrity of intestinal epithelial cells and the TJ complex between epithelial cells in fish. The potential protective effects of Gln against glycinin toxicity were also investigated. The results of this study will allow us to determine some of the reasons for the negative effects of high doses of dietary SBM, and provide some insights into the resolution methods.

Methods

The Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University approved all experimental procedures (B-20081106).

Experimental diets, fish trial and sampling

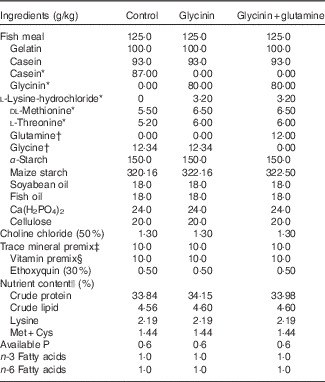

Purified glycinin was kindly provided by China Agricultural University (patent no. 200410029589·4, China). The ingredients and nutrient content of the experimental diets are shown in Table 1. Fish meal, gelatin and casein were used as the dietary protein sources. An 80 g glycinin/kg diet was used in this study to investigate the toxic effects and the corresponding mechanisms according to the following concerns. It is well-known that glycinin accounts for approximately 40 % of the total soyabean proteins( Reference Utsumi, Matsumura and Mori 25 ). Our previous study observed that high levels (347, 517·8 and 685·8 g/kg diet) of de-hulled SBM (protein content=47 %) significantly impaired growth and seriously disrupted the intestinal integrity in juvenile Jian carp( Reference Zhang, Zhou and Liu 26 ). In addition, a dosage of 12·0 g Gln/kg used to block the negative effects of glycinin was proven to be optimal for the intestinal health of Jian carp in our previous study( Reference Lin and Zhou 23 ). All diets were made isonitrogenous. Briefly, glycinin was made isonitrogenous, and amino acids were balanced with the addition of reduced amounts of casein and modulated amino acids and compensated with appropriate amounts of maize starch according to a previous study( Reference Sun, Li and Li 27 ), whereas Gln was made isonitrogenous with the addition of reduced amounts of glycine and compensated with appropriate amounts of maize starch according to our previous study( Reference Lin and Zhou 23 ). In the diets, lysine, methionine, threonine, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, thiamine, pyridoxine, inositol, Fe and Zn were properly added to meet the nutrient requirements of juvenile Jian carp according to our previous laboratory studies( Reference Jiang, Feng and Liu 28 , Reference Jiang, Liu and Hu 29 ). The levels of other nutrients were designed to meet the requirements of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) according to the NRC (2011). The diets were stored at −20°C until feeding, as in our previous study( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ).

Table 1 Ingredients and nutrient contents of the diets

* Glycinin was made isonitrogenous, and amino acids were balanced with the addition of reduced amounts of casein and modulated amino acids and compensated with appropriate amounts of maize starch according to a previous study( Reference Sun, Li and Li 27 ).

† Glutamine was made isonitrogenous with the addition of reduced amounts of glycine and compensated with appropriate amounts of maize starch according to our previous study( Reference Lin and Zhou 23 ).

‡ Per kg of mineral premix (g/kg): FeSO4·7H2O (19·7 % Fe), 69·695 g; CuSO4·5H2O (25·0 % Cu), 1·201 g; ZnSO4·7H2O (22·5 % Zn), 21·640 g; MnSO4·H2O (31·8 % Mn), 4·089 g; KI (3·8 % I), 2·895 g; NaSeO3 (1·0 % Se), 2·500 g. All ingredients were diluted with CaCO3 to 1 kg.

§ Per kg of vitamin premix (g/kg): retinyl acetate (172 g/kg vitamin A), 0·800 g; cholecalciferol (12·5 g/kg vitamin D), 0·480 g; d, l-α-tocopherol acetate (50 %), 20·000 g; menadione (50 %), 0·200 g; cyanocobalamin (10 %), 0·010 g; d-biotin (20 %), 0·500 g; folic acid (96 %), 0·521 g; thiamin nitrate (98 %), 0·104 g; ascorhyl acetate (92 %), 7·247 g; niacin (98 %), 2·857 g; meso-inositol (98 %), 52·857 g; calcium-d-pantothenate (98 %) 2·511 g; riboflavine (80 %), 0·625 g; pyridoxine hydrochloride (98 %), 0·755 g. All ingredients were diluted with maize starch to 1 kg.

|| Crude protein and crude lipid contents were determined according to the method of AOAC (1998). Lysine, Met+Cys, available P, n-3 and n-6 fatty acids contents were calculated according to NRC (1993).

The juvenile Jian carps (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian) used in this study were purchased from a local hatchery. Before the trial, the fish were acclimatised to the experimental environment (the water temperature and pH were 23 (sd 1) and 7·0 (sd 0·3)°C, respectively; dissolved oxygen was higher than 5 mg/l; the aquaria were supplied with flow-through water at a rate of 1·2 l/min; and the water was drained through biofilters to remove solid substances and reduce ammonia concentration) for 4 weeks. After adapting, 450 fish with a mean initial weight of 5·37 (sd 0·02) g were randomly assigned to each of nine experimental aquaria (90 length×30 width×40 cm height). In the feeding trial, each diet was fed to a triplicate of fish six times per d for the first 4 weeks and four times per d for the 5th and 6th week, a feeding rhythm that was established in our laboratory previously( Reference Xiao, Feng and Liu 30 ). The fish were fed to apparent satiation. After 30 min of feeding, uneaten feed was removed by siphoning, and it was dried and weighed later to calculate feed intake.

At the beginning and end of the trial, fish in each aquarium were counted and weighed. After that, fish were anaesthetised in a benzocaine bath (50 mg/l) 12 h after the last feeding according to the method of Bohne and our previous study( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 , Reference Bohne, Hamre and Arukwe 31 ). After killing the fish, their intestines were quickly removed on ice, rinsed in cold physiological saline (0·9 % NaCl solution, pH=7·2), weighed, measured and frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until they were analysed according to the methods described in previous studies( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 , Reference Qu, Wang and Feng 32 ). The intestines of another six fish from each aquarium were sampled and fixed with formalin (10 %), sectioned and stained with haematoxylin–eosin stain for analysis of height of intestinal folds according to the method in our previous study( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ).

Biochemical analysis

According to the method in a previous study( Reference Qu, Wang and Feng 32 ), with slight modifications, the intestine samples were homogenised on ice in ten volumes (w/v) of ice-cold physiological saline and centrifuged at 6000 g for 20 min at 4°C, and then the supernatant was used for biochemical analysis.

Intestinal function indexes, such as AKP, Na+/K+-ATPase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) and creatine kinase (CK), were determined according to the procedure described by Bessey et al. ( Reference Bessey, Lowry and Brook 33 ), Weng et al. ( Reference Weng, Chiang and Gong 34 ), Bauermeister et al. ( Reference Bauermeister, Lewendon and Ramage 35 ) and Tanzer & Gilvarg( Reference Tanzer and Gilvarg 36 ), respectively. In the assay enzymes, 1 U of activity was considered as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol of product/h, except γ-GT, which calculated as per min.

ROS were measured according to the method described by Gornicka et al. ( Reference Gornicka, Fettig and Eguchi 37 ) with a slight modification – intestinal tissue homogenates were used in this study instead of adipose tissue homogenates in the referenced study. The values of ROS are expressed as the multiple of the levels of the control group according to the method described by a previous study( Reference Xu, Zhou and Zhang 38 ). Lipid peroxidation was analysed in terms of malondialdehyde (MDA) equivalents using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reaction as a previous study described( Reference Qu, Wang and Feng 32 ). In brief, samples were mixed with TCA and centrifuged. Then, TBA was added to the supernatant. The mixture was heated in water at 95°C for 40 min. MDA forms a red adduct with TBA, which has an absorbance of 532 nm. The protein carbonyl (PC) residue content was determined as previously described( Reference Baltacıoğlu, Akalın and Alver 39 ), using the 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine reagent. The carbonyl content was calculated from the peak absorbance at 340 nm, using an absorption coefficient of 22 000/M/cm. The protein contents of the intestines were determined according to a previous study( Reference Bradford 40 ), which were used to calculate the following parameters involved. MDA and PC are all denoted by nmol/mg protein.

The total superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activities were assayed as a previous study described( Reference Zhang, Zhu and Cai 41 ). Briefly, for SOD, the reaction mixture contained 50 mm-phosphate buffer (pH=7·8), 1·08 mm-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DETAPAC), 0·06 mm-nitro blue tetrazolium, 0·16 mm-xanthine solution and 30 μl of samples. After the addition of 0·19 U/ml of xanthine oxidase, the absorbance change at 550 nm was monitored. For GPx, the reaction mixture consisted of tissue homogenates, 40 μl of 0·25 mm-hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), 10 mm-sodium phosphate buffer (pH=7·0), 0·5 mm-glutathione (GSH) and 1·25 mm-NaN3 in a total volume of 1 ml. After 3 min intervals, 0·5 ml of dithiobisnitrobenzoic acid was added. A yellow product formed as GSH reacts with dithiobisnitrobenzoic acid, which was monitored at 412 nm. The catalase (CAT) activities were measured as in our previous study( Reference Jiang, Feng and Liu 42 ). The assay mixture consisted of 100 mm-KPO4 buffer (pH=7·0), 10 mm-H2O2 and 50 μl of intestinal homogenates in a total volume of 1 ml. The decrease of H2O2 was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 240 nm. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) activity was measured by monitoring the formation of the adduct of GSH and 1-chloro–2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB)( Reference Lushchak, Lushchak and Mota 43 ). The reduced GSH was determined using the method described in a previously described study( Reference Vardi, Parlakpinar and Ozturk 44 ). An adduct between GSH and CDNB was monitored at 340 nm. Together, with the exception of SOD, in which 1 U of activity was considered a half of inhibition of absorbance in comparison with tube lacking enzyme according to the method described by Datkhile et al. ( Reference Datkhile, Mukhopadhyaya and Dongre 45 ), in the assay enzymes 1 U of activity was considered as the amount of enzyme required to transform 1 μmol of substrate/min.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

In this study, total RNA was extracted according the procedure of our previous study( Reference Jiang, Liu and Hu 29 ). Briefly, total RNA of the intestines was extracted using RNAiso Plus (D9108B; Takara Biotechnology, Dalian Co. Ltd), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quantity and quality were assessed by electrophoresis on 1 % agarose gels and spectrophotometric analysis (A260:280 nm ratio). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesised using a PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, oligo dT primers were used to reverse transcribe respective RNAs in the presence of PrimeScriptTM RT enzyme Mix I, 5×PrimeScriptTM buffer, Random 6 mers and RNase-free dH2O at 37°C for 15 min, following inactivation at 85°C for 5 s.

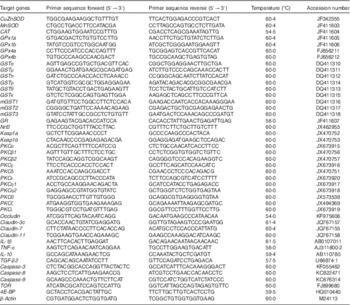

The specific primers for the genes were designed with Primer Premier Software (Premier Biosoft International) based on the carp sequences (Table 2). According to the results of our preliminary experiment concerning the evaluation of internal control genes, β-actin was used as a reference gene to normalise cDNA loading. The quantitative RT-PCR assays were conducted using the relative standard curve method described by Wang et al. ( Reference Wang and Gallagher 46 ). Standard curves were generated for the target genes and the endogenous control gene β-actin (Table 2) based on 10-fold serial dilutions. Gene expression quantities were normalised against β-actin, and ratios for the treated samples were calculated via comparisons with the expressions in control animals.

Table 2 Real-time PCR primer sequences

CAT, catalase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GR, glutathione reducase; GSH, glutathione; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; PKC, protein kinase C; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TGF-β2, transformed growth factor-β2; TOR, target of rapamycin.

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as the means and standard deviations. Data were subjected to one-way ANOVA. When a significant difference was observed (P<0·05), Tukey’s test of significance was used to resolve the difference. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc.).

Results

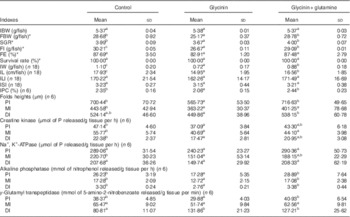

Effects of glycinin on the growth performances and intestinal growth and function of fish

The fish growth performance and intestinal growth and function results are presented in Table 3. The results indicated that compared with the control group treatment with glycinin alone significantly decreased the final body weight (FBW), specific growth ratio (SGR), feed intake (FI), intestinal weight (IW), intestinal protein content (IPC), intestinal length (IL) and fold heights in the PI and MI of fish (P<0·05). Upon co-treatment with Gln, the FBW, SGR, FI, IW, IPC, IL and fold heights in the PI and DI significantly increased compared with those of fish exposed to glycinin alone (P<0·05), and the FBW, SGR and IPC values and fold heights in the PI and DI completely recovered to become equivalent to those of the control group. However, no significant differences were found in the feed efficiency, survival rate and intestinal length index and intestinal somatic index among the treatments (P>0·05).

Table 3 Growth performance and intestinal growth of juvenile Jian carp (Cyprinus crpio var. Jian) exposed to dietary glycinin for 42 d (Mean values and standard deviations)

IBW, initial body weight; FBW, final body weight; SGR, specific growth ratio; FI, feed intake; FE, feed efficiency; IW, intestinal weight; IPC, intestinal protein content; IL, intestinal length; ILI, intestinal length index; ISI, intestinal somatic index; PI, proximal intestine; MI, mid intestine; DI, distal intestine.

SGR=100×(ln final weight−ln initial weight)/number of days.

FE=100×(weight gain (g)/feed intake (g)).

ILI=100×(intestine length (cm)/total body length (cm)).

ISI=100×(wet intestine weight (g)/wet body weight (g)).

IPC=100×(intestine protein (g)/wet intesitine weight (g)).

a,b,c Mean values within a row with unlike superscript letters are significantly different (P<0·05).

* Fifty fish in each group.

Intestinal function indexes demonstrated that dietary glycinin exposure alone depressed the activities of creatine kinase and AKP in the PI, MI and DI; the activity of Na+ and K+-ATPase in the MI; and the activity of γ-GT in the PI of fish (P<0·05). When co-treated with Gln, the activity of AKP in the PI, MI and DI and the γ-GT activity in the PI were significantly increased when compared with those of fish exposed to glycinin alone (P<0·05), and even those values completely recovered to be equivalent to the control. However, glycinin alone caused increases in the γ-GT activity in the DI of fish, whereas that co-treated with Gln had no significant effects on this index. No significant differences were found in the Na+, K+-ATPase activity in the PI and DI, as well as γ-GT activities in the MI among the treatments (P>0·05).

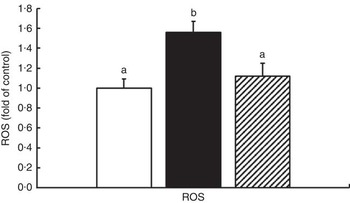

Effects of glycinin on the oxidative status and antioxidant-related parameters in the intestines of fish

The oxidative status and antioxidative enzyme activities in the intestines of fish are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 4. With the administration of glycinin alone, ROS, MDA and PC contents in the intestines of fish increased significantly (P<0·05), and co-administration of glycinin and Gln caused the ROS and MDA content to recover to the levels similar to the control levels. However, there was no significant change in the intestinal PC content in fish between the glycinin alone group and the group with glycinin plus Gln (P>0·05). In addition, the activities of SOD, CAT, GST and GR in the intestines of fish were decreased in fish treated with glycinin compared with the unexposed controls (P<0·05). Except for intestinal GST, those activities reduced by glycinin exposure recovered with the co-treatment of Gln to be equivalent to the control values (P>0·05). GPx activity in the co-treatment with glycinin and Gln group is higher than that in the glycinin alone group. GSH was not significantly different between the control group and the glycinin alone group, whereas it significantly increased with the co-treatment of glycinin and Gln in the intestines of fish (P<0·05).

Fig. 1 Effects of different treatments on the reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the intestine of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

Table 4 Oxidative status and antioxidant abilities in the intestine of juvenile Jian carp exposed to dietary glycinin for 42 d (Mean values and standard deviations of six replicates)

MDA, malondialdehyde (nmol/mg protein); PC, protein carbonyl content (nmol/mg protein); GSH, glutathione content (mg/g protein); SOD, superoxide dismutase (U/mg protein); CAT, catalase (U/mg protein); GST, glutathione-S-transferase (U/mg protein); GPx, glutathione peroxidase (U/mg protein); GR, glutathione reductase (U/g protein).

a,b Mean values within a row with unlike superscript letters are significantly different (P<0·05).

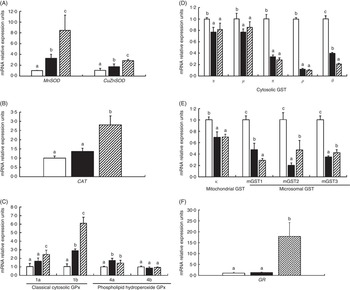

Effects of glycinin on the mRNA levels of MnSOD, CuZnSOD, catalase, four isoforms of glutathione peroxidases, nine isoforms of glutathione-S-transferases and glutathione reducase genes in the intestines of fish

To investigate the effects of glycinin on the transcription of antioxidant enzymes in the intestines of fish, the mRNA levels of CuZnSOD, MnSOD, CAT, four isoforms of GPx, nine isoforms of GST and GR in the intestine of fish were determined (Fig. 2). The results indicated that dietary glycinin exposure significantly increased the MnSOD, CuZnSOD, GPx1b and GPx4a mRNA levels, but decreased the mRNA levels of GST α, GST μ, GST π, GST ρ, GST θ, GST κ, mGST1, mGST2 and mGST3. The GPx1a, GPx4b, CAT and GR mRNA levels were not changed by dietary glycinin exposure in the intestines of fish. The highest mRNA levels of MnSOD, CuZnSOD, CAT, GPx1a, GPx1b and GR, and the lowest mRNA levels of GST θ and mGST1 were observed in the intestines of fish fed the glycinin plus Gln diet (P<0·05). However, no significant difference in the mRNA expression of GPx4a, GPx4b, GST α, GST μ, GST π, GST ρ and GST κ were observed between the glycinin alone group and the glycinin plus Gln group.

Fig. 2 Effects of different treatments on the mRNA levels of CuZnSOD, MnSOD (A), catalase (CAT) (B), four isoforms of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) (C), nine isoforms of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) (D, E) and glutathione reducase (GR) (F) in the intestine of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

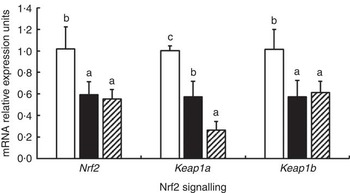

Effects of glycinin on the antioxidant-relative signalling factors in the intestines of fish

The effects of glycinin on the mRNA levels of Nrf2 signalling-related factors in the intestines of fish are presented in Fig. 3. The results indicated that glycinin exposure alone significantly decreased mRNA levels of Nrf2, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1a (Keap1a) and Keap1b in the intestines of fish compared with the unexposed control group (P<0·05). Diets supplemented with glycinin and Gln did not change the Nrf2 and Keap1b mRNA levels (P>0·05), but they significantly decreased the Keap1a mRNA levels (P<0·05).

Fig. 3 Effects of different treatments on the mRNA levels of Nrf2 and Keap1 in the intestine of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

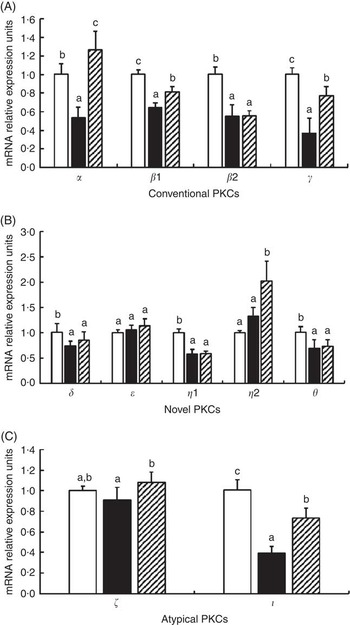

The effects of glycinin on the mRNA levels of eleven isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC) are presented in Fig. 4. The results indicated that glycinin significantly decreased the mRNA levels of conventional PKC (α, β1, β2 and γ). However, glycinin has different effects on the novel PKC and atypical PKC. It decreased the mRNA levels of PKC δ, η1, θ and ι but did not have significant effects on the PKC η2, ε and ζ mRNA levels. In addition, interestingly, except for PKC β2, the decreased mRNA levels of conventional PKC (including PKC α, β1 and γ) and atypical PKC (including ζ and ι) in fish fed the glycinin alone diet were partially or completely reversed, whereas the novel PKC (including PKC δ, ε, η1 and θ) except PKC η2 in the intestines of fish were not changed in fish with glycinin plus Gln.

Fig. 4 Effects of different treatments on the mRNA levels of eleven isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC) in the intestine of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

Effects of glycinin on the tight junction protein transcript abundance in the intestines of fish

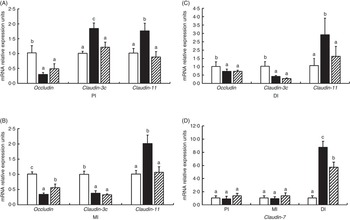

Fig. 5 presents the relative levels of occludin, claudin-3c, claudin-11 and claudin-7 mRNA in the PI, MI and DI of fish exposed to dietary glycinin. Compared with the control fish, glycinin significantly down-regulated the expression of occludin in all intestinal segments and claudin-3c in the MI and DI (P<0·05) and up-regulated the expression of claudin-3c in the PI, claudin-11 in all intestinal segments and claudin-7 in the DI (P<0·05), whereas there was no significant change in the expression of claudin-7 in the PI and MI (P>0·05). Co-administration of glycinin and Gln demonstrated significant increases in the mRNA levels of occludin in the MI and significant decreases of the mRNA levels of claudin-3c in the PI, claudin-11 in all intestinal segments and claudin-7 in the DI. However, no significant changes in the mRNA levels of occludin in the PI and DI, claudin-3c in the MI and DI and claudin-7 in the PI and MI were observed when comparing the glycinin plus Gln group with the group of glycinin exposed alone.

Fig. 5 Effects of different treatments on the mRNA levels of occludin, claudin-3c, claudin-11 (A, B, C) and claudin-7 (D) in the proximal intestine (PI), mid intestine (MI) and distal intestine (DI) of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

Effects of glycinin on the relative mRNA levels of cytokines in the intestines of fish

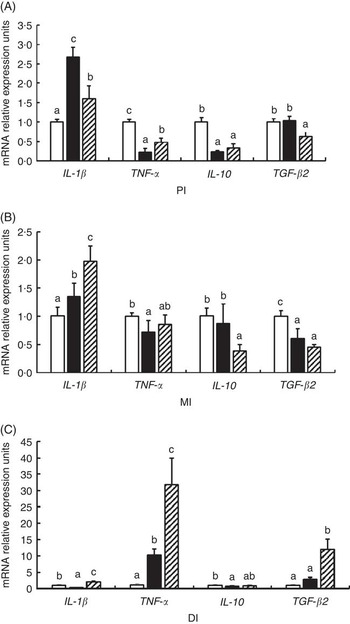

As shown in Fig. 6, glycinin significantly down-regulated the mRNA levels of IL-1 β in the DI, TNF- α in the PI and MI and IL-10 in the PI and DI, and transformed growth factor-β2 (TGF-β2) in the MI (P<0·05) and up-regulated the mRNA levels of IL-1 β in the PI and MI, and TNF- α in the DI (P<0·05), whereas it caused no significant change in the mRNA levels of IL-10 in the MI and TGF- β2 in the PI and DI (P>0·05). Co-administration of glycinin and Gln resulted in significant reductions in the mRNA levels of IL-1 β in the PI, IL-10 in the MI and TGF-β2 in the PI (P<0·05) and significant increases in the mRNA levels of IL-1 β in the MI and DI, TNF- α in the PI and DI and TGF- β2 in the DI (P<0·05), whereas it resulted in no significant change in mRNA levels of TNF- α and TGF- β2 in the MI and IL-10 in the PI and DI as compared with the group of glycinin (P>0·05).

Fig. 6 Effects of different treatments on the mRNA levels of IL-1

β, TNF-

α, IL-10 and transformed growth factor-β2 (TGF-

β2) in (A) the proximal intestine (PI), (B) mid intestine (MI) and (C) distal intestine (DI) of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

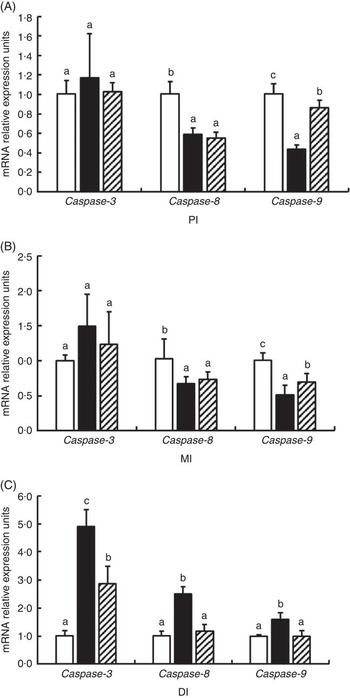

Effects of glycinin on the mRNA levels of the caspase-3, 8 and 9 in the intestines of fish

The mRNA levels of caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 in the PI, MI and DI are presented in Fig. 7. Glycinin significantly increases the mRNA levels of caspase-3 in the DI and caspase-8 and caspase-9 in the DI (P<0·05) and reduced the mRNA levels of caspase-8 and caspase-9 in the PI and MI of Jian carp (P<0·05). Co-administration of glycinin and Gln resulted in significant decreases in the mRNA levels of caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 in the DI (P<0·05), and increases in the mRNA levels of caspase-9 in the PI and MI (P<0·05), whereas it resulted in no significant change in the mRNA levels of caspase-3 and caspase-8 in the PI and MI of Jian carp when compared with the glycinin alone group (P>0·05).

Fig. 7 Effects of different treatments on the mRNA levels of caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 in (A) the proximal intestine (PI), (B) mid intestine (MI) and (C) distal intestine (DI) of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

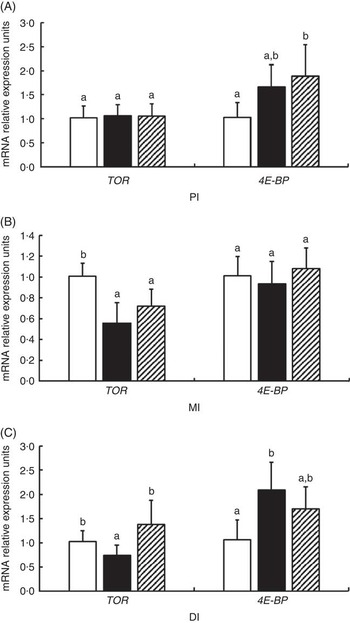

Effects of glycinin on the mRNA levels of target of rapamycin and 4E-BP in the intestines of fish

The mRNA levels of TOR and 4E-BP genes in the PI, MI and DI of fish are presented in Fig. 8. Significant reductions in TOR mRNA levels caused by glycinin alone were observed in the MI and DI, and the reduction in the DI of fish was completely blocked by Gln supplementation (P<0·05). However, Gln failed to significantly block the reduction of TOR by glycinin exposure in the MI of fish. Furthermore, there were no changes in the TOR mRNA levels in the PI of fish among the three groups. As for 4E-BP, the results indicated that glycinin increased the mRNA levels in the DI (P<0·05), whereas it caused no significant change in the PI and MI of fish (P>0·05). Upon treatment with Gln, the 4E-BP mRNA levels recovered to the control levels in the DI (P>0·05) and increased to higher than the control levels in the PI of fish (P<0·05). In addition, no significant effect was observed in the MI of fish supplemented with glycinin and Gln (P>0·05).

Fig. 8 Effects of different treatments on the mRNA levels of target of rapamycin (TOR) and 4E-BP in (A) the proximal intestine (PI), (B) mid intestine (MI) and (C) distal intestine (DI) of Jian carp. Values are means of six replicates with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P<0·05). Gln, glutamine; □, control; ■, glycinin; ![]() , glycinin+Gln.

, glycinin+Gln.

Discussion

Soyabean protein is a source of high-quality protein in fish diets( Reference Collins, Desai and Mansfield 47 ). However, our previous study observed that high doses of dietary SBM could depress the growth of fish( Reference Zhang, Zhou and Liu 26 ). Glycinin is a primary storage protein, and it has long been recognised as one of the allergens in soyabeans( Reference Holzhauser, Wackermann and Ballmer-Weber 48 ). Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the mechanisms whereby excessive SBM induces growth depression in animals utilising purified soyabean glycinin.

Glycinin-depressed fish growth performance and impaired intestinal growth and function of fish

In terms of growth performance, the present study found that dietary glycinin decreased the fish growth rate and impaired feed intake, which was also observed in piglets( Reference Zhao, Qin and Sun 5 ). However, the survival rate was not influenced by the dietary treatments. Although no reports exist concerning the effects of glycinin on the survival rate in fish, similar findings were observed in our previous study with β-conglycinin, another allergen in soyabean protein( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ). In addition, fish growth is strongly related to intestinal growth and function( Reference Wen, Feng and Jiang 8 ). To our knowledge, intestinal brush border enzymes, such as AKP, Na+, K+-ATPase, γ-GT and CK, are considered to reflect intestinal function in fish( Reference Chen, Feng and Kuang 49 ). The present study demonstrated that dietary glycinin exposure alone decreased the IW, IL and IPC, and reduced the fold heights and creatine kinase, Na+, K+-ATPase, AKP and γ-GT activities in some intestinal segments of fish, suggesting that glycinin could impair the growth and function of the intestines in fish. Similar results of decreased jejunum villus height caused by dietary glycinin exposure were found in rats( Reference Ma, He and Sun 50 ). However, those results do not agree with a recent study that found that glycinin had no significant effects on the fold heights and AKP activities in the mid gut and hind gut of juvenile turbot Scophthalmus maximus ( Reference Gu, Bai and Xu 51 ). There are at least three reasons for those differences. First, it may be partially because of the different doses. This study administered an 80 g glycinin/kg diet, which was higher than that in the juvenile turbot study (60 g glycinin/kg diet)( Reference Gu, Bai and Xu 51 ). Second, in this study, the fish were exposed to dietary glycinin for 6 weeks, which was longer than the exposure in the juvenile turbot study (4 weeks)( Reference Gu, Bai and Xu 51 ). Third, turbot is a carnivorous fish with a stomach( Reference Gu, Bai and Xu 51 ), whereas this study used carp, which is an omnivorous fish without a stomach. Furthermore, fish intestinal growth and function are associated with the structural integrity( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ). To our knowledge, oxidative damage has been linked to the disruption of intestinal barrier integrity, cell injury and dysfunction( Reference Wen, Feng and Jiang 8 ). Thus, we next investigated whether glycinin-depressed intestinal growth and function are related to the oxidative damage and the potential mechanism in the intestines of fish.

Glycinin-induced oxidative damage and its potential mechanism in the intestines of fish

Glycinin caused oxidative damage in the intestines of fish

Our results first demonstrated that dietary glycinin exposure resulted in elevation of the ROS, MDA and PC contents in the intestines of fish, suggesting that excessive dietary glycinin exposure could cause oxidative damage in fish intestines. Previous studies in our laboratory indicated that oxidative damage was often accompanied by the depression of the antioxidant capacity( Reference Chen, Zhou and Feng 9 , Reference Jiang, Liu and Hu 29 ). Thus, we next investigated the effects of dietary glycinin exposure on the intestinal antioxidant capacity of fish.

Glycinin exposure impaired the antioxidant system in the intestines of fish

GSH is the major endogenous antioxidant scavenger that protects cells from oxidative stress( Reference Liang, Sheng and Jiang 52 ). Surprisingly, the present study found no significant changes in the GSH content in the intestines of fish following dietary glycinin exposure. It was reported that GSH synthesis in endothelial cells occurs through a process that requires the activity of γ-GT( Reference Moellering, Mc Andrew and Patel 53 ). In this study, increases in γ-GT activity in the DI might correspond to a first attempt to overcome oxidative stress by producing a high amount of GSH. In addition, the present study observed decreases in the SOD, CAT, GST and GR activities in the intestines of fish exposed to dietary glycinin alone. These results indicated that the intestinal oxidative damage caused by glycinin might be partially related to the suppression of the antioxidant capacity of carp. The antioxidant enzyme activities are closely related to their mRNA levels in fish( Reference Fontagné-Dicharry, Lataillade and Surget 54 ). Thus, we next investigated the effects of glycinin on antioxidant enzyme mRNA levels in the intestines of fish.

Interestingly, although the activities of most antioxidant enzymes were decreased by glycinin exposure, different gene expression patterns of some enzymes were observed in the intestines of fish. For instance, dietary glycinin exposure caused decreases in the activities of SOD, CAT and GR but increased the mRNA levels of CuZnSOD and MnSOD isoforms, whereas it did not change the mRNA levels of CAT and GR significantly. In addition, although dietary glycinin exposure did not change the activity of GPx significantly, it increased the mRNA levels of GPx1b and GPx4a isoforms and had no significant effects on the mRNA levels of GPx1a and GPx4b isoforms. The different patterns between gene mRNA levels and their corresponding enzyme activities might be partially explained by two factors. First, the increases in mRNA levels of antioxidant enzymes indicated an adaptive mechanism that fish intestines need more de novo synthesis of those antioxidant enzymes for scavenging excess ROS, but those antioxidant enzyme activities were constantly inactivated by the ROS that resulted from dietary glycinin exposure, and we thus observed no changes or decreases in enzyme activities. Similar results were observed in our previous study with fish exposed to another dietary anti-nutrient factor β-conglycinin( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ). Second, it might be related to influences on enzyme activities that occurred not only at the gene transcriptional level but also at the post-transcriptional (such as translation, post-translational modification and so on) levels, just as Ferro et al. ( Reference Ferro, Franchi and Mangano 55 ) indicated.

The GSTs represent an important group of enzymes that detoxify both endogenous compounds and foreign chemicals such as pharmaceuticals and environmental pollutants( Reference Nebert and Vasiliou 56 ). According to subcellular localisation, GSTs consists of cytosolic GST (α, μ, π, ρ and θ), mitochondrial GST κ and microsomal GST (mGST1, mGST2 and mGST3)( Reference Uno, Murayama and Kunori 57 , Reference He, Liang and Sun 58 ). Interestingly, this study observed that glycinin exposure caused decreases in the mRNA levels of all nine isoforms of GST, coinciding with GST enzyme activities. The decreases in the mRNA levels of nine GST isoforms by dietary glycinin exposure might partially explain the decreased GST activity in this group and also indicates an inhibition of the de novo synthesis of those nine GST isoforms, thus causing a dysfunction of detoxification in the cytosolic, mitochondrial and microsomal proteins in the intestines of fish.

The gene transcripts of antioxidant enzymes are regulated by intracellular signalling pathways in mammals( Reference Itoh, Wakabayashi and Katoh 59 ). Recently, a central role of Nrf2 pathways in regulating antioxidant enzyme gene transcriptions has emerged in terrestrial animals( Reference Niture, Jain and Jaiswal 60 ), zebra fish( Reference Nakajima, Nakajima-Takagi and Tsujita 61 ) and Jian carp( Reference Jiang, Liu and Jiang 13 ). Thus, we next investigated the effects of glycinin exposure on the Nrf2 signalling in the intestines of fish.

Glycinin impaired antioxidant-related Nrf2 signalling factor transcription in the intestines of fish

In the current study, the relative expression of Nrf2 genes in the intestines of fish was depressed by glycinin exposure, suggesting that decreases in the mRNA levels of nine isoforms of GST caused by glycinin might be partially related to the reduced Nrf2 gene transcription in fish intestines. Nrf2 nuclear translocation is a critical event for provoking gene transcription of antioxidant enzymes in HT29 human colon carcinoma cell( Reference Boettler, Sommerfeld and Volz 62 ). Keap1, a cytoplasmic protein, binds to the actin cytoskeleton and traps Nrf2, thereby preventing the nuclear translocation of this transcription factor in mice( Reference Kang, Kobayashi and Wakabayashi 63 ). It has been reported that the down-regulation of Keap1 gene expression in murine lungs stimulated nuclear translocation of Nrf2, thus evoking the transcription of Nrf2 target genes( Reference Blake, Singh and Kombairaju 64 ). However, this study observed that glycinin exposure caused decreases in the expression of Keap1a and Keap1b. Those results may be partially related to the depressed Nrf2 regulation. It was reported that the Keap1 gene promoter contains a functional antioxidant response element sequence, which could be up-regulated by Nrf2 in mouse hepatoma cells( Reference Lee, Jain and Papusha 65 ). Thus, the decreases in Keap1a and Keap1b mRNA levels might be partially related to the decreased Nrf2 mRNA levels.

In terrestrial animals, the inhibition of PKC was indicated to decrease the accumulation of free-Nrf2 nuclear translocation( Reference Niture, Jain and Jaiswal 60 ). Meanwhile, PKC also have many roles, such as the regulation of many cellular processes, including division, proliferation, survival, anoikis and polarity in terrestrial animals( Reference Martin-Liberal, Cameron and Claus 66 ). The PKC isoforms are grouped into three classes: conventional forms (α, β1, β2 and γ), which are activated by Ca2+/diacylglycerol, novel forms (δ, ε, η1, η2 and θ), which are activated by diacylglycerol alone, and atypical forms (ζ and ι), which are diacylglycerol-independent terrestrial animals( Reference Gilio, Harper and Cosemans 67 ). Interestingly, this study observed that glycinin exposure significantly decreased the mRNA levels of conventional PKC (α, β1, β2 and γ). However, it has different effects on the novel PKC and the atypical PKC. It decreased the mRNA levels of PKC δ, η1, θ and ι, but did not affect the PKC η2, ε and ζ mRNA levels. Those observations indicated a possible relationship between glycinin-induced decrease in the de novo synthesis of PKC (α, β1, β2, γ, δ, η1, θ and ι) and the reduction of Nrf2 signalling in fish.

In addition to the integrity of intestinal epithelial cells, intestinal health has been correlated with the intestinal physical barrier, which primarily comprises TJ proteins in fish( Reference Wen, Feng and Jiang 8 ). TJ can be influenced by cytokines and apoptosis( Reference Bruewer, Luegering and Kucharzik 68 ). Cytokine production and apoptosis can be modulated by TOR signalling( Reference Zeng, Wang and Shi 21 , Reference Umemura, Park and Taniguchi 69 ). Thus, we next investigated the effects of dietary glycinin on the TJ, cytokines, apoptosis and TOR signalling in the intestines of fish.

Glycinin impaired intestinal tight junctions and modulated cytokines and apoptosis signalling, which is partially related to changes in target of rapamycin signalling in the intestines of fish

Several lines of evidences support a barrier-forming role for occludin, claudin-3c and claudin-11 in fish( Reference Chasiotis and Kelly 70 , Reference Chasiotis, Kolosov and Kelly 71 ), whereas claudin-7 appears to possess pore-forming characteristics( Reference Krause, Winkler and Piehl 72 ). In the present study, dietary glycinin exposure significantly decreased the mRNA levels of the barrier-forming TJ, occludin and claudin-3c in the MI and DI, and increased the mRNA levels of the pore-forming TJ, claudin-7 in the DI, whereas it did not change the mRNA levels of claudin-7 in the PI and MI of fish. However, in the PI, although dietary glycinin exposure decreased occludin mRNA levels, it also increased claudin-3c mRNA levels. Meanwhile, we observed that dietary glycinin exposure induced adaptive increases in the mRNA levels of claudin-11 in the PI, MI and DI of fish. These results indicated that glycinin exposure could impair some of the TJ components, the seriousness of which followed the order DI>MI>PI. These results might partially explain a previous report that SBM-induced pathohistological changes primarily occurred in the DI of fish( Reference Krogdahl, Bakke McKellep and Baeverfjord 73 ). The reasons for serious glycinin-induced impairment of the TJ in the DI>MI>PI are largely unknown but might be partially associated with the apoptosis and the inflammatory cytokines. It was reported that the intestinal TJ could be destroyed by apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokines( Reference Capaldo and Nusrat 18 , Reference Bruewer, Luegering and Kucharzik 68 ). Thus, we next investigated the effects of glycinin on the apoptosis signalling and the cytokines in the intestines of fish.

It was reported that pro-inflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis-independent mechanisms( Reference Bruewer, Luegering and Kucharzik 68 ). In general, caspase-3 is the major executioner caspase in the caspase-dependent pathway( Reference Gao, Xu and Qiao 74 ). Meanwhile, apoptotic pathways are mainly classified into the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway and the extrinsic (death ligand) pathway, and these classifications could be regulated by caspase-9 and caspase-8, respectively( Reference Sharifi, Eslami and Larijani 75 ). In this study, dietary glycinin exposure increased the mRNA levels of all of the apoptosis signalling, including caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 in the DI of juvenile fish, whereas it decreased caspase-8 and caspase-9 mRNA levels in the PI and MI of fish. These results indicated that glycinin-induced apoptosis signalling primarily occurred in the DI of fish, which followed a similar pattern to the effects of glycinin on intestinal TJ, indicating a possible relationship between glycinin-induced disruption of intestinal TJ and apoptosis signalling in fish. Although the patterns of apoptosis signalling are similar to the TJ patterns, the cytokines observed disorder patterns. For instances, glycinin exposure caused pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1 β mRNA levels to increase and TNF- α mRNA levels to decrease in the PI and MI, whereas the IL-1 β mRNA levels decreased and the TNF-α mRNA levels increased in the DI of fish. For anti-inflammatory cytokines, glycinin exposure decreased only IL-10 mRNA levels in the PI and DI, and decreased only the TGF- β2 mRNA levels in the MI of fish. The reasons for these disorder patterns for cytokines are largely unknown but might be partially related to the different exposure time course in the PI, MI and DI of fish during the process when fish intake and digest feed. Studies have shown that the expression of three pro-inflammatory cytokine genes (IL-1 β, IL-8 and TNF- α) in the liver of juvenile salmons differed in the exposure timing and magnitude( Reference Fast, Johnson and Jones 76 ).

The TOR signalling pathway is a well-known pathway to regulate translation initiation, the limiting step in protein synthesis in animals( Reference Tsukumo, Laplante and Parsyan 77 ). Recently, it has been observed that the inhibition of TOR signalling promoted cell apoptosis and induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production( Reference Zeng, Wang and Shi 21 , Reference Hu, Zhang and Feng 78 ). However, the up-regulation of 4E-BP could inhibit TOR signalling( Reference Tain, Mortiboys and Tao 79 ). This study observed that dietary glycinin exposure alone decreased the TOR mRNA levels in the MI and DI and increased the 4E-BP mRNA levels in the DI, whereas it did not change the TOR and 4E-BP mRNA levels in the PI of fish. These observations indicated that glycinin exposure could inhibit TOR signalling in the MI and DI, more seriously in the DI than in the MI of fish. These effects followed similar patterns to the effects on the TJ and apoptosis signalling, suggesting that glycinin-induced TJ damage and apoptosis signalling were partially related to the inhibition of TOR signalling. However, a study from our laboratory observed that fish exposed to another dietary anti-nutrient factor, β-conglycinin, also caused the down-regulation of TOR signalling, but this change primarily occurred in the PI and MI( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ). Considering those two studies together might partially explain how high doses of SBM impaired the intestinal structural integrity and caused poor growth of the fish observed in a previous study( Reference Krogdahl, Bakke McKellep and Baeverfjord 73 ).

Protective effects of glutamine against glycinin-induced negative effects on intestinal health and the growth performance of fish

Gln serves as a major fuel for intestinal epithelial cells in mammals( Reference Windmueller 80 ). Our previous study has demonstrated that dietary Gln supplementation could improve growth performance and the intestinal structure and function in Jian carp( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ). According to these findings, we investigated the potential protection of Gln against glycinin toxicity in the present study. Interestingly, compared with the glycinin alone groups, for fish administered Gln with glycinin, the performance parameters (FBW, SGR and FI), intestinal growth (IW, IL, IPC and folds heights) and functional (activities of CK, Na+, K+-ATPase, AKP and γ-GT) indicators, as well as intestinal structural integrity indexes (ROS and MDA content, activities of SOD, CAT, GPx, GST and GR) were partially or completely close to or equal to those in the control group, demonstrating that Gln might mitigate the negative effects on fish growth and intestinal health caused by glycinin. Similar results of Gln against another dietary anti-nutrient factor, β-conglycinin, induced intestinal oxidative damage in juvenile Jian carp, as observed in our previous study( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ). Those positive effects might be partially because of the fact that Gln has protective and reparative roles against oxidative damage. Our previous studies observed that co-treatment or post-treatment with Gln could protect or repair fish enterocytes from oxidative damage caused by H2O2 ( Reference Chen, Zhou and Feng 9 , Reference Hu, Feng and Jiang 81 ). Thus, because Gln was observed to mitigate the negative influences of glycinin or β-conglycinin observed in our previous study( Reference Zhang, Guo and Feng 24 ), it is reasonable for us to recommend supplementation with Gln when high levels of SBM (glycinin and β-conglycinin) are used in fish diets.

Conclusion

In this study, we report five primary, novel and interesting results. (1) Dietary glycinin exposure could depress the growth performance of fish, which might be partially related to the dysfunction of the intestines, which are the digestive/absorptive organs in stomach-less fish. (2) The dietary glycinin-induced poor growth and dysfunction of the intestines might be partially associated with the intestinal cellular oxidative damage and disruption of the cell–cell TJ. (3) The glycinin-induced intestinal cellular oxidative damage was, at least in part, related to the impaired enzymatic antioxidant ability (decreased SOD, CAT, GST and GR activities) and disturbed antioxidant enzyme gene expression, inducing adaptive increases in MnSOD, CuZnSOD, CAT, GPx1b and GPx4a mRNA levels, and decreasing the mRNA levels of nine GST isoforms. Meanwhile, dietary glycinin exposure also disturbed the antioxidant-related signalling factor mRNA levels, including Nrf2, Keap1a, Keap1b and eleven isoforms of PKC. (4) Dietary glycinin exposure-induced disruption of the cell–cell TJ was partially related to the modulation of cytokines, apoptosis and TOR signalling in the following order of seriousness DI>MI>PI. (5) Because Gln was observed to mitigate the negative influences of glycinin, it is reasonable for us to recommend supplementation with Gln when high levels of SBM (glycinin) are utilised in fish diets.

Acknowledgements

The present study was jointly supported by National Department Public Benefit Research Foundation (Agriculture) of China (X.-Q. Z., grant number 201003020), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (Y.-A. Z., grant number 2014CB138600), Science and Technology Support Program of Sichuan Province of China (X.-Q. Z., grant number 2014NZ0003), Major Scientific and Technological Achievement Transformation Project of Sichuan Province of China (X.-Q. Z., grant numbers 2012NC0007, 2013NC0045), the Demonstration of Major Scientific and Technological Achievement Transformation Project of Sichuan Province of China (X.-Q. Z., grant number 2015CC0011), Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientists of Sichuan Province (L. F., grant number 2014JQ0007) and Sichuan Province Research Foundation for Basic Research (L. F., grant number 2013JY0082). The funding agencies had no role in the design and analysis of the study or in the writing of this article.

The author’s contributions are as follows: X.-Q. Z. and L. F. designed the study; W.-D. J., K. H. and J.-X. Z. conducted the study and analysed the data; Y. L., J. J., P. W., J. Z. S.-Y. K., L. T. W.-N. T. and Y.-A. Z. participated in the interpretation of the results; W.-D. J., K. H. and J.-X. Z. wrote the manuscript; X.-Q. Z. had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.