1. Introduction

In several previous publications,Footnote 1 I have argued that Hittite knows in its synchronic stop system a series of ejective stops (/t’ː/, etc.),Footnote 2 which etymologically go back to earlier clusters of stops + laryngeals.Footnote 3 These ejective stops form a third series next to the two series that are traditionally called “fortis” and “lenis”, and which can be phonologically interpreted as plain long stops (/tː/, etc.) and plain short stops (/t/, etc.), respectively.Footnote 4 My postulation of a series of ejectives is primarily based on the fact that in the spelling of dental stops before the vowel a, in some environments three different orthographic practices can be discerned. In these cases, two of the three spelling patterns can be analysed as denoting the fortis and lenis stops, respectively, whereas the third orthographic pattern, which always involves spellings with the sign DA, correlate with the etymological presence of a cluster of dental stop + laryngeal, *TH. Since in the Old Babylonian version of the cuneiform script, which forms the source of the Hittite ductus, the sign DA can be used to designate the ejective stop [t’], I have proposed that in Hittite, too, these spellings with DA indicate the presence of ejective stops.Footnote 5

My proposal concerns the following three environments. First, in word-initial position, the dental ejective is marked by virtually consistent spelling with the sign DA (e.g. da-an-zi “they take” = [t'antsi] < *dh3enti). This spelling contrasts with consistent spelling with the sign TA, which marks the presence of [t] = fortis /tː/, and with alternating spelling of TA and DA, which marks the presence of [d] = lenis /t/.Footnote 6 Second, in intervocalic position, the dental ejective is predominantly indicated by geminate spelling with the sign DA (e.g. ud-da-a-ar “words” = [ut’ːaːr] < *uth2ōr).Footnote 7 This contrasts with consistent geminate spelling with the sign TA, which marks the presence of [tː] = fortis /tː/, and alternating single spelling with TA and DA, which marks the presence of [d] = lenis /t/.Footnote 8 And, finally, in post-consonantal position, the dental ejective is indicated by virtually consistent spelling with the sign DA (e.g. an-da “into” = [ənt'a]Footnote 9 < *h1ndhh2e). This contrasts with consistent spelling with the sign TA, which marks the presence of [t] = fortis /tː/, and alternating spelling of TA and DA, which marks the presence of [d] = lenis /t/.Footnote 10

Some colleagues have indicated to find my analysis of these spellings difficult to accept.Footnote 11 For instance, Kim (Reference Kim, Guzzo and Taracha2019: 2987) states that he is “not convinced” of my postulation of a three-way contrast in the Hittite stop system, but does not specify his problems with my analysis, and does not treat the data on which this analysis is based. In the same vein, Patri (Reference Patri2019: 1005) formulates some problems with my 2010 paper,Footnote 12 but does not mention my 2013 paper. Lastly, Melchert (Reference Melchert, Kim, Mynářová and Pavúk2020) does not specifically mention my postulation of ejective stops in Hittite, but he does list my 2010 and 2013 articles as examples of phonological studies that are based on “the widespread pernicious false premise that all non-random orthographic patterns must at all costs reflect linguistically real contrasts” (emphasis his), whereas to his mind such patterns may rather be due to “established norms, aesthetic considerations, and pure convention” (Melchert Reference Melchert, Kim, Mynářová and Pavúk2020: 259). I fundamentally disagree with this latter view: it is the task of historical linguists to explain the rationale behind specific spelling peculiarities. Especially when synchronic, statistically significant orthographic patterns correlate with a specific etymological phonological sequence (in this case, for instance, the fact that synchronic spellings of the type (-)Vd-da(-) correlate with Proto-Indo-European (PIE) clusters of the type *-TH-, whereas consistent spelling of the type (-)Vt-ta(-) corresponds to PIE *-t-), and one can make likely that this orthography could represent a synchronic phonation that would fit its etymological origins (in this case, in Old Babylonian the spelling (-)Vd-da(-) is used to write the ejective stop [t’ː], whereas (-)Vt-ta(-) in principle denotes plain [tː]), Occam's Razor demands that we should postulate this phonation for the synchronic stage of the language in question (in this case that Hitt. (-)Vd-da(-) represents [t’ː], which contrasts with (-)Vt-ta(-) = [tː]).Footnote 13 Assuming that such patterns are based on “established norms” or “convention”, as Melchert is implying, without explaining why these norms arose, is nothing more than saying that one has not been able to find a linguistic rationale, and therefore does not constitute an explanation at all.

As long as no alternative explanation is offered to explain the correlation between synchronic DA-spellings and etymological clusters of dental stops + laryngeals, I see no reason to abandon my postulation of ejective stops in Hittite.

2. The problem: a single long ejective series

The geminate spelling (-)Vd-da(-) that is used to denote the intervocalic ejective stops in e.g. uddār “words”, padda-i “to dig”, etc., indicates that they were long consonants. This is not only the case when they etymologically go back to a PIE voiceless stop + laryngeal (e.g. uth2ōr > uddār [ut’ːaːr] “words”), but also when they reflect a cluster of a PIE voiced (aspirated) stop + laryngeal (e.g. *bhodhh2-V° > padda-i “to dig” [pat’ːa-]). I have therefore argued that in the latter case, the original lenis (short) outcome of PIE *d(h) underwent fortition (lengthening) before the laryngeal, which by that time had developed into a glottal stop, after which the fusion of the cluster of fortis (long) stop + glottal stop yielded a long ejective stop: e.g. PIE *bhodhh2V° > pre-Hitt. [potʔV-], which underwent fortition to *[potːʔV-], resulting into Hitt. [pat’ːV-], spelled pád-da- “to dig” (Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst2013: 130–1). In the case of word-initial and post-consonantal ejective stops, there is no indication in spelling that these consonants were long, however, and it is therefore best to assume that they were phonetically short, [t’]. In Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst, Kim, Mynářová and Pavúk2020: 173, I argued that intervocalic long [t’ː] and word-initial and post-consonantal short [t’] may phonologically be regarded as allophones of a single ejective phoneme, for which I assumed the basic shape /t’ː/.Footnote 14 This allophony would thus be similar to the one found in the case of the plain fortis stop /tː/, which is realized as a long stop [tː] in intervocalic position, but as short [t] in word-initial and post-consonantal position. I did note a problematic aspect of this analysis, however, namely that “[o]ne could argue […] that in this way [the phoneme /t’ː/] is redundantly marked vis-à-vis the fortis and the lenis stops (/tː/ and /t/, respectively)” and that, when it comes to segmental features, it would be more economic to interpret this phoneme as an underlying short ejective stop /t’/. However, “since in intervocalic position the consonantal length is relevant for whether the preceding vowel stands in an open or closed syllable, I rather keep the long character of the ejective stop expressed in my phonemic representation of it” (Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst, Kim, Mynářová and Pavúk2020: 173).

Nevertheless, I kept feeling uneasy about this situation: long ejective stops are cross-linguistically rare, and, as far as I am aware, only occur in phoneme inventories in which they contrast with a series of short ejective stops.Footnote 15 In the following paragraphs I will present a solution to this problem: I will argue that Hittite also knew a series of short ejective stops.

3. Intervocalic short ejective stops?

The Hittite verbs pēda-i / pēd- “to bring (away)” and uda-i / ud- “to bring (here)” are transparent univerbations of the verb dā-i / d- “to take” with the preverbs pē- “thither” and u- “hither”, respectively. Both verbs contain an intervocalic single spelled dental stop, and in the case of uda-i, the spelling of this stop is remarkable.

Normally, in Old Script (OS) texts, intervocalic single spelled dental stops always show interchange between spellings with DA and with TA (e.g. a-da-an-zi / a-ta-an-zi “they eat”), which, as I have argued, denotes the presence of a voiced stop [d], the intervocalic allophone of lenis /t/ < PIE *d(h).Footnote 16 However, as noted in Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst2013: 13960, in the case of uda-i we find in OS texts consistent spelling with the sign DA (31x ú-da-), but no spelling with the sign TA (never **ú-ta-). In this way, this verb deviates in spelling from the words that contain an intervocalic [d] = /t/. However, since the corresponding verb pēda-i does show in OS texts an interchange between spellings with DA (30x pé(-e)-da(-)) and with TA (14x pé(-e)-ta(-)), which does more or less match the spelling practices of intervocalic [d], I decided to brush aside the consistent spelling of uda-i as ú-da-, and assumed for both verbs the presence of an intervocalic [d]. I did remark, however, that “I do not want to exclude the possibility […] that in these words the use of the sign DA in the sequence °V-da(-) represents the presence of a short glottalized stop, [-Vtʔa-], which then must have been taken over from the base verb dā-i/d- “to take”, which had the shape [tʔ(ā)-]” (Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst2013: 13960).

In the meantime I have come to the conclusion that this latter interpretation is the more likely one. This is based on the fact that it is very difficult to envisage a historical scenario that would account for the presence of a lenis stop /t/ = [d] in pēda-i and uda-i.

4. The prehistory of pēda-i and uda-i

In the older literature, it is assumed that the initial consonant of dā-i / d-, which reflects PIE *d- (from the root *deh3-), for a long time during the prehistory of Hittite had the value of a lenis stop. Only in recent pre-Hittite times (after the assibilation of *ti̯- > [ts-] and *d(h)i̯- > [s-] had taken place), word-initial fortis and lenis dental stops merged into a single, short voiceless stop [t-], which phonologically can be viewed as a fortis consonant. Within this framework, it was easy to account for a lenis /t/ in pēda-i and uda-i: one would just have to assume that the univerbation of pē- and u- + dā-i took place when its initial stop was still lenis.Footnote 17

However, with the recognition that, because of its consistent spelling with the sign DA (e.g. 1sg.pres. da-a-aḫ-ḫi, 3sg.pres. da-a-i, 3pl.pres. da-an-zi, etc.), the verb dā-i / d- must have had an initial ejective stop, [t’ā-, t’-], this scenario can no longer be upheld.

4.1. The prehistory of dā-i / d-

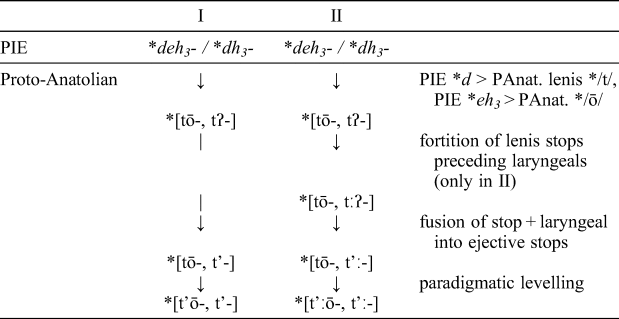

As mentioned above, the Hittite ejective stops are the result of a fusion of original clusters of stop + laryngeal, in this case *dh3-. It should be noted that in the verb *deh3- / *dh3- this cluster was originally only present in the weak stem *dh3-, which implies that at some moment in time a paradigmatic levelling has taken place. As Norbruis (Reference Norbruis2021: 423, fn. 2) argues on the basis of Luwian evidence,Footnote 18 both the fusion of *dh3- to a monophonemic stop and its levelling throughout the paradigm must have taken place in pre-Proto-Anatolian times. Moreover, there is another relevant pre-Proto-Anatolian development that needs to be taken into account, namely the contact-induced fortition of lenis stops when standing before laryngeals, which in intervocalic position is attested both in Hittite (e.g. mekki- “much, many” < *meǵh2-i-) and in Luwian (CLuw. 2pl.midd. -dduu̯ar < PIE *-dhh2uo°). Since this development must have taken place when the laryngeal was still an independent phoneme, it follows that it must have preceded the fusion of such clusters into ejective consonants. Although it cannot be excluded that this fortition only took place in word-internal, postvocalic position, it is possible that it also affected word-initial clusters.Footnote 19 All in all, we may envisage two possible pathways of developments of PIE *deh3- / *dh3- in pre-Proto-Anatolian (see Table 1): pathway I (without fortition of *[tʔ-] > *[tːʔ-]), which would yield PAnat. *[t’ō-, t’-]; and pathway II (with fortition of *[tʔ-] > *[tːʔ-]), which would yield PAnat. *[t’ːō-, t’ː-].

Table 1 The two possible pathways of developments of PIE *deh3- / *dh3- in pre-Proto-Anatolian.

As was mentioned earlier, in the prehistory of Hittite the plain dental stops, fortis *[tː-] and lenis *[t-], merged in word-initial position into a single short voiceless [t-]. Although this [t-] phonologically should be regarded as a fortis stop (Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst, Kim, Mynářová and Pavúk2020: 166), phonetically the merger is caused by the shortening of fortis *[tː-] to [t-]. We may thus assume that such a shortening would have affected PAnat. word-initial *[t’ː-] as well, yielding [t’-]. So in the case of pathway II, in which the PAnat. shape of this verb is *[t’ːō-, t’ː-], with long ejectives, we may now add another, specifically pre-Hittite development: *[t’ːō-, t’ː-] > *[t’ō-, t’-] (shortening of *[t’ː-] to [t’-]). Together with the specifically pre-Hittite colouring of PAnat. */ō/ to Hitt. /ā/, we end up with Hitt. [t’ā-, t’-]. In the case of pathway I, in which the PAnat. shape of this verb is *[t’ō-, t’-], no shortening needs to be assumed, only the colouring of the vowel of the strong stem, after which the result is Hitt. [t’ā-, t’-]. In this way, the outcome of both pathways is the same, Hitt. [t’ā-, t’-], which is spelled dā-i / d-.

4.2. The creation of pēda-i and uda-i

As said above, the verbs pēda-i / pēd- and uda-i / ud- are the result of a univerbation of the verb dā-i / d- with the preverbs pē- and u-, which phonetically were [pḗ] and [ʔū́], respectively.Footnote 20 The exact moment of univerbation is not fully clear, but there are no indications that point to a Proto-Anatolian origin of these verbs.Footnote 21 It is therefore best to assume that they are specifically Hittite formations. Within pathway I, this means that at the moment of univerbation their base verb had the shape *[t’ā-, t’-]. Within pathway II, there are two stages: before the shortening of word-initial *[t’:-] to [t’-], which means that at that moment in time the base verb had the shape *[t’ːō-. t’ː-]; or after the shortening, which is equal to pathway I.

Within pathway II, if the univerbation took place in its initial stage, i.e. before the shortening of *[t’:-] to [t’-], we would expect the outcomes of the univerbations to have been [pḗt’ːa-, pḗt’ː-] and [ʔū́t’ːa-, ʔū́t’ː-], respectively.Footnote 22 According to the spelling rules of Hittite, these verbs would then have been spelled with geminate spelling: **pé-e-ed-da- and **ú-ud-da-, respectively. Since these spellings do not occur, we can safely rule out this scenario.Footnote 23

If these verbs were formed with the base verb [t’ā-, t’-] (within pathway I, and during the second stage of pathway II), the expected outcomes would be [pḗt'a-, pḗt’-] and [ʔū́t'a-, ʔū́t’-], respectively. We would expect that the short ejective consonant in these forms would be spelled with single spelling, °V-Ca(-). In the case of the long ejective stop /t’ː/, we have seen that it is predominantly spelled with geminate spelling with the sign DA, (-)Vd-da(-), although spellings with the sign TA, (-)Vt-ta(-), do occasionally occur as well.Footnote 24 This would predict that a short ejective stop would be predominantly spelled with the sign DA as well, °V-da(-), next to some spellings with the sign TA, °V-ta(-). These predictions are a perfect match with the way pēda-i and uda-i are spelled. Both show single spelling of their dental stop, and both show predominant spellings with the sign DA. In the case of pēda-i, CHD (P: 345–6) lists 171 attestations with the sign DA, vs. 30 with the sign TA (a ratio of 85.1% DA vs. 14.9% TA). In the case of uda-i, I have found in my files over 470 attestations with the sign DA, vs. only oneFootnote 25 with the sign TA (a ratio of 99.8% DA vs. 0.2% TA). These ratios correspond almost exactly to the ratios between DA and TA spellings that are found in the lexemes that contain a long ejective stop [t’ː] (which ranged from 100% DA vs. 0% TA (padda-i “to dig”) to 94.6% DA vs. 5.4% TA (uddar / uddan- “word, thing”), 91.4% DA vs. 8.6% TA (paddar / paddan “basket”), 89.3% DA vs. 10.7% TA (apadda(n) “there, thither”), and 86.1% DA vs. 13.9% TA (piddae-zi “to flee”), cf. Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst, Kim, Mynářová and Pavúk2020: 150–3).

For the sake of argument, we may also discuss the possibility that the univerbations of pē- and u- with the base verb dā-i / d- took place in pre-Proto-Anatolian times, that is, before the spread of the initial consonant of the weak stem *[t’-] (in pathway I) or *[t’ː-] (in pathway II) throughout the paradigm. The phonologically regular outcome of the strong stem, [pḗ] / [ʔū́] + *[tō-], would then be [pḗda-] and [ʔū́da-], respectively, with a lenis dental [d]. In the weak stem, however, we would expect an outcome [pḗt’-] and [ʔū́t’-], with a short ejective stop [t’] (according to pathway I), or [pḗt’ː-] and [ʔū́t’ː-], with a long ejective stop [t’ː]Footnote 26 (according to pathway II). The result would be paradigms with consonantal alternation between strong and weak stem: [pḗda-, pḗt’(ː)-] and [ʔū́da-, ʔū́t’(ː)-]. In other verbs for which we can reconstruct a similar consonantal alternation between a strong and a weak stem, it is always the weak stem that is generalized. For instance, PIE *ti-ne-h1-ti / *ti-nh1-énti should regularly have yielded Hitt. **zinizzi / zinnanzi ([tsini-, tsinː-]), with lenis -n- in the strong stem and fortis -nn- in the weak stem, but in the prehistory of Hittite this has been levelled out to zinnizzi / zinnanzi, with generalization of the fortis -nn- of the weak stem. On the basis of this and many other examples, we would have to assume that the original paradigms **[pḗda-, pḗt’(ː)-] and **[ʔū́da-, ʔū́t’(ː)-] would have been levelled out either to [pḗt'a-, pḗt’-] and [ʔū́t'a-, ʔū́t’-] (according to pathway I), or to [pḗt’ːa-, pḗt’ː-] and [ʔū́t’ːa-, ʔū́t’ː-] (according to pathway II), in both cases with the ejective stop of the weak stem being generalized throughout the paradigm. As we have seen above, the outcomes with a long ejective stop (according to pathway II), should in Hittite have been spelled **pé-e-ed-da- and **ú-ud-da-, respectively, which is not what we find. The outcomes with a lenis ejective stop (according to pathway I) would formally be identical to the outcomes of the pre-Hittite univerbations of pathway I (and the second stage of pathway II), for which the spellings pé-e-da- and ú-da- are a perfect match.

4.3. The synchronic interpretation of pēda-i and uda-i

All in all, we can conclude that the only way to combine the fact that pēda-i and uda-i show single spelling of their dental stop with the recognition that their base verb, dā-i / d- contained an ejective stop, is by assuming that the dental stop of pēda-i and uda-i was a short ejective stop [t’]: [pḗt'a-] and [ʔū́t'a-]. This is the only possible outcome of these univerbations, whether they were created in pre-Hittite times (pathway I or during the second stage of pathway II) or in pre-Proto-Anatolian times (pathway I). There simply is no scenario by which the dental stop of pēda-i and uda-i could be a plain lenis dental stop [d] = /t/, and I therefore regard the presence of a short ejective stop [t’] in these verbs as certain.

5. A revision of the Hittite stop system: two series of ejective stops

Since the intervocalic ejective [t’] of pēda-i and uda-i is in spelling consistently distinguished from its long counterpart [t’ː] (e.g. ud-da-a-ar [ut’ːaːr] “words”, pád-da- [pat’ːa-] “to dig”), we must assume that they were two different phonemes, /t’/ and /t’ː/, respectively. As a consequence, we should enlarge the Hittite phoneme inventory – at least for the dental place of articulation – with a series of short ejective stops, which contrast with their long counterparts.Footnote 27

A major advantage of this analysis, and in fact an extra argument in favour of it, is that in this way we solve the problem that was formulated in section 2: the length of the intervocalic ejective stops of words like uddār, padda-i, etc., which originally seemed phonologically redundant, can now be seen as a distinctive feature that contrasts with the absence of length in the newly discovered ejective stops of pēda-i and uda-i.

The distinction between the dental short and long ejective stops seems to have been made in intervocalic position only: pēda-i “to bring away” = /pḗt'a-/, uda-i “to bring here” = /ʔū́t'a-/ vs. uddār “words” = /ut’ːā́r/, padda-i “to dig” = /pat’ːa-/, etc. As far as I am aware, in word-initial position and post-consonantal position, no contrast between long and short ejective stops can be discerned, and given the fact that in these positions the ejective stops phonetically are probably short, it is best to phonemically interpret them as short as well: dā-i / d- “to take” = /t’ā-, t’-/, dai-i / ti- “to put” = /t'ai-, t'i-/, daššu- “dense” = /t'asːu-/; anda “into” = /ənt'a/, andan “inside” = /ənt'an/.Footnote 28

As argued in Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst2010: 216–17, also for the velar place of articulation there is direct evidence for ejective stops, namely in the verb kinu-zi, ginu-zi “to open up” = [k'inu-]Footnote 29 < PIE *ǵhh2i-neu-. Etymologically, we would expect the presence of intervocalic long ejective velar stops as well, for instance in mekki- “much, many”, which reflects PIE *meǵh2-i- and therefore synchronically probably was [mek’ːi-].Footnote 30 Thus far, however, no specific spelling practice has been identified with which these sounds can be distinguished from plain fortis stops, so their existence must, for the time being, remain hypothetical. Nevertheless, in analogy to the situation in the dental series, I regard it likely that also in the velar series the word-initial short ejective [k’-] can now be interpreted as a separate phoneme vis-à-vis the long ejective [k’ː] that probably was present in words like mekki-.

Unfortunately, for the labial and labiovelar place of articulation we have at the moment no secure evidence for any ejective stops, so here it is best to remain agnostic.

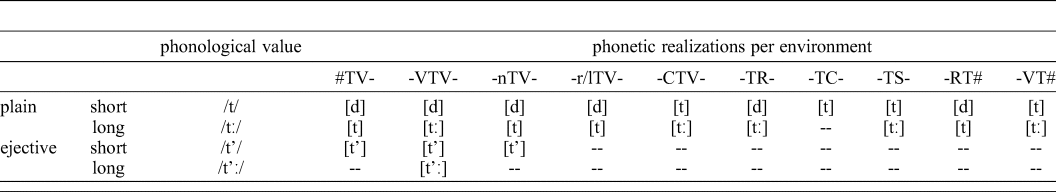

All in all, an updated overview of the Hittite stop system should look as follows:

I also present here an updated version of the table of the phonetic realizations of the dental stop phonemes in different environments as presented in Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst, Kim, Mynářová and Pavúk2020: 172 (originally given with only three phonemes, but here with four, and with different ordering; moreover, I have added the environment -TS-, based on the outcome of Kloekhorst Reference Kloekhorst2019).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sasha Lubotsky as well as the anonymous reviewer from BSOAS for useful comments on an earlier version of this article.