It is our desire that they be protected and treated civily, but we positively expect you should not assist them in buying or selling goods or permitt it to be done by any under you at that Castle or any other of our factories on the coast

-RAC instructions to its factors at Cape Coast Castle on treating the “Ten Percenters”Footnote 1The early modern world saw the growth of three interrelated phenomena: capitalism, corporations, and the transatlantic slave trade. Over the past decade, scholars have traced the myriad linkages between the rise of capitalism and the exploitation of enslaved labor. Older narratives connecting plantation slavery and the accumulation of capital from the transatlantic slave trade to the prosperity of Europe and the United States have been complemented by more recent work, which takes a fine-grained look at the way that enslaved and other kinds of unfree labor systems fostered the development of modern capitalist practices and state formation.Footnote 2 Recent studies focusing on accounting practices, insurance measures, commodity chains, and pharmaceuticals have all shown the more subtle ways in which slavery and capitalism bolstered one another.Footnote 3 All in all, this more recent strand of literature has revealed a dark side of sophisticated forms of capitalist organization, destabilizing implied progressive narratives of economic development.

But the foundational link between capitalism and slavery had a specific form of business organization at its core. Initially developed in the context of growing long-distance trade to Asia, corporations quickly became the de facto organizational structure of the transatlantic slave trade. The development of corporations for long-distance trade marked a significant departure from traditional forms of business organization for long-distance commerce. As vehicles for passive capital accumulation and impersonal investing, corporations allowed those without family ties to enter into long-distance commercial ventures. By 1700, the new corporate model changed the structure of long-distance trade, enabling capital accumulation and subsequent commercial expansion on an unprecedented scale.Footnote 4 As Ron Harris has suggested, the corporation as a business innovation was not only instrumental to the specific type of capitalism that flourished in the West, but also may have even laid a foundation for the Great Divergence.Footnote 5

While corporations were central to the development and acceleration of the transatlantic slave trade in the seventeenth century, little is known about the connections between the slave trade and the corporate form. How did the development of the corporation and the development of the slave trade reinforce each other? To what extent could the corporation hedge against risk and face competition in the African trade? The synergistic relationship between corporations and the slave trade cannot be separated from the political economic context in which they were embedded, as state-sponsored monopolies dominated the late seventeenth-century slave trade. The trajectories and ultimate fates of this relatively new form of business organization were in many cases deeply intertwined with the states and mercantilist worldviews that had produced them. When the policies and worldviews of those in power changed, so did the economic landscape in which corporations operated.

In early modern England, the political landscape changed with the Glorious Revolution in 1688. The aftermath of the revolution brought with it a major shock in corporate history, as the company lost royal support. The revocation of the Royal African Company's (RAC) African trade monopoly in 1698 inaugurated an era of free trade by Europeans on the Atlantic African coast, ultimately transforming the slave trade as a whole. The RAC had been the largest single participant in the slave trade at the end of the seventeenth century, constituting almost 60 percent of all British slaving vessels, and 30 percent of the total number of slave ships that sailed in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. While the RAC faced some competition from interlopers during its monopoly period, Figure 1 shows that the end of the monopoly brought with it an unparalleled increase in the English slave trade. The end of the company's monopoly and the ensuing wave of private traders not only pressured the RAC itself but also posed a commercial threat to all monopoly corporations engaged in the slave trade.Footnote 6 While this structural shift reached the RAC's foreign competitors through its ripple effect, it presented an immediate and first-order shock to the company.Footnote 7

Figure 1. RAC voyages and total number of British slave voyages, 1672-1730. Notes: The figure counts all British voyages that arrived in the Americas between 1672 and 1730. Voyages that did not have a value for the category of “owner” in the database were counted as non-RAC voyages. (Source: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, accessed 3 Sep. 2022, https://www.slavevoyages.org/.)

Ultimately, the Royal African Company folded, unable to compete with the waves of private traders who flocked to the coast.Footnote 8 By the early 1730s, the company had almost completely pulled out of the slave trade, and by 1750 it collapsed altogether.Footnote 9 The existing literature on the RAC has analyzed reasons for the company's failure.Footnote 10 But even though we know the end of the story now, it was not apparent at the time, least of all to the men controlling the RAC in London. Faced with the sudden end of its monopoly position, how did the company respond? What strategies did it develop to navigate this new competitive landscape in Atlantic Africa?

To better understand how the RAC navigated this critical moment, we exploit a rare series of instruction letters that the company issued to its slave-ship captains before they left England for Africa. The Royal African Company archives contain a series of 292 letters of instruction that the company issued its captains between 1685 and 1706.Footnote 11 We transcribed and coded the complete series, which covers nearly all of the RAC voyages in this period listed in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (TASTD) (83 percent, see also Table 3). While historians have used letters and other private writings like diaries to great effect to analyze business practices in the past, the structure and near-complete nature of this series of letters, however, allows us to use such qualitative source materials in a novel way.Footnote 12 The instructions that the RAC issued its captains are highly systematic in nature; they follow a formula with series of standard paragraphs, repeated commands, and stock phrases detailing each component of the trip.Footnote 13 It is exactly this formula—and the way the formula changed over time—that is the key to understanding the company in motion. Through exploiting this formula by coding individual commands in the letters, we can analyze how the RAC responded in real time to the existential crisis that the end of the monopoly posed.

Our new database reveals two major insights about the Royal African Company that have so far gone unnoticed. First, the company exhibited a remarkable degree of flexibility throughout the monopoly and immediate post-monopoly periods. In the monopoly era, the RAC learned by doing, continually adopting new measures to more effectively manage all aspects of the slave voyage. The company in London also quickly responded to changing international military circumstances, adding new instructions to safeguard its vessels and valuable information aboard them during times of war with the French. Second, our data reveals that the company quickly responded to the shock of the loss of its monopoly, building on the adaptive framework it had developed in the preceding decades. The influx of new competitors after the revocation of the monopoly in 1698 exacerbated the company's principal-agent problem with its fort factors on the West African coast, as the factors now had additional opportunities to cheat the company. The Royal African Company swiftly responded to this new threat by turning to a monitoring mechanism it had at its disposal: the infrastructure of the slave trade itself. Because slave ships continually left Europe to sail to West Africa and then to the Americas before returning home, the company had a steady source of potential monitors traveling to company forts. Following the fall of its monopoly privileges, the RAC began to instruct its slave-ship captains to surveil fort factors, overturning the traditional hierarchical relationship between captains and factors.

The Royal African Company's response to the loss of its monopoly shows that the company was not doomed to fail from the outset, but rather fought hard for its position in the immediate post-monopoly era. The company is therefore a classic example of the phenomenon of “running to stand still.”Footnote 14 The ultimate failure of the RAC masks innovation in the strategy and management practices of the company. Our data-driven approach to this critical period of the RAC's existence gives us a new window into the flexibility of the early modern corporate form and its role in the emergence of the modern capitalist world.

The Corporation as a New Business Model

In the pre-industrial world, economic growth was predominantly driven by the intensification of trade.Footnote 15 In the second millennium, long-distance trade—both in goods and in slaves—became an increasingly important component of global commercial activity, overcoming limitations in the size of domestic markets. While merchants could reap great financial gains from long-distance trade, it was a challenging business for those who engaged in it. For one, long-distance trade was riskier than local trade, as it connected merchants to commercial arenas with weaker market signals. Quite simply, it was harder to know a distant market well and bringing the wrong trade items could spell financial disaster. Long-distance trade also brought with it a series of physical risks, exposing traders to foreign disease environments and placing them at the mercy of others for shelter, safety, and supplies. Because long-distance merchants tended to carry lighter, high-value luxury goods, they were vulnerable to attack as well.Footnote 16 These general risks were amplified for merchants traveling beyond their own empires, who had to contend with different political systems, languages, cultural preferences, and customs. Additionally, long-distance trade was more challenging financially than local trade. Merchants who wanted to engage in this type of trade faced both larger upfront costs in terms of the capital needed to initiate a long-distance venture and higher transaction costs because of the uncertainties involved in distant business transactions. Moreover, because of the distances involved, merchants also had to wait for long periods of time before they could benefit financially from their investments.

Such challenges, however, did not remain static over time, as actors who engaged in long-distance commerce developed new institutions to mitigate risk and scale up the volume of trade. In Europe, the commercial revolution of the twelfth century saw the birth of business practices that have long been considered foundational to the development of Western capitalism.Footnote 17 In particular, the institution of the commenda split merchant capital, which stayed at home, from the party traveling to undertake the business transaction.Footnote 18 More recent scholarship has dismantled some of the Eurocentrism that characterized older interpretations, showing that these new types of partnerships were not unique to Europe, but emerged organically in other parts of the world as well, or migrated there.Footnote 19 Nonetheless, in all of these arrangements, the separation of passive investors from the active commercial party introduced a range of principal-agent problems in long-distance trade. In this new business model, investors had to trust their commercial partners to carry out the negotiating work according to their wishes and not to undercut them.

Around 1600, the evolution of commercial institutions underpinning long-distance trade in Europe took another big leap. As Harris has recently argued, the business corporation acquired a number of its modern features in the early seventeenth century, merging pre-existing practices of limited liability with new concepts of joint-stock equity finance, the lock-in of investment, and the transferability of interest.Footnote 20 This transition to a large-scale shareholder model of commercial investment allowed for unprecedented levels of capitalization and mitigated risk in new ways. At the same time, this new model of corporate organization amplified the principal-agent problems inherent in long-distance trade.Footnote 21

These new companies were dependent on state legal and institutional support for long-distance commercial success. As emphasized by Andrew Phillips and J. C. Sharman, the changing geopolitical landscape in Europe at least in part triggered the development of joint-stock companies for long-distance trade in England and the United Provinces.Footnote 22 The growing strength of the Habsburg Empire, based in no small part on its commercial ties to the Americas and Asia, constituted an existential crisis for English and Dutch rulers, prompting them to recast their relationship with long-distance trade as key to their survival. Unlike the Portuguese model, in which long-distance trade operated as a direct “arm of the state,” the Dutch and English backed long-distance trading companies by endowing them with specific economic and sovereignty privileges, such as monopoly rights and the authorization to wage war.Footnote 23 The hallmark of this new state-backed corporate form were the Dutch and English East India Companies (the VOC and EIC, respectively), which soon came to dominate European oceanic trade with Asia.Footnote 24

While this new model for long-distance trade was initially developed to break into and gain the upperhand in the Indian Ocean trade, it soon proliferated in the Atlantic trade as well. As illustrated in Tables 1 and 2, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw the establishment of numerous monopoly companies that sought profits from the expanding trade with Africa, the West Indies, and North America. However, these other commercial contexts turned out to be less hospitable than the Indian Ocean trade to this new corporate form. With the exception of the Hudson's Bay Company, few companies that operated in the Atlantic World were able to replicate the success of the EIC and VOC, and none lasted as long or were as stable.Footnote 25

Table 1 Major Early Modern Joint-Stock Companies with Monopolies in the Asian Trade

Sources: For the EIC and Darien Company, see Phillips and Sharman, Outsourcing Empire, 146 and 105. For the VOC, see Oscar Gelderblom, Abe de Jong, and Joost Jonker, “The Formative Years of the Modern Corporation: The Dutch East India Company VOC, 1602–1623,” The Journal of Economic History 36 (2013), 1054. For the Compagnie des Indes, see Robert Stein, The French Slave Trade in the Eighteenth Century: An Old Regime Business (Madison, 1979), 11–14; Dibadj “Compagnie Des Indes.” For the Danish Ostindisk Company, see Ole Feldbæk, “The Danish Trading Companies of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Scandinavian Economic History Review, 34, no. 3 (1986): 204–218. For the Swedish Ostindiska Companiet, see Adam Andersson, An Historical and Chronological Deduction of the Origin of Commerce (Robson, 1787), 174; Klas Rönnbäck and Leos Müller, “Swedish East India Trade in a Value-Added Analysis, c. 1730–1800,” Scandinavian Economic History Review 70, no. 1 (2020): 1–18. For the Oostendse Compagnie, see Jelten Baguet, “Politics and Commerce: A Close Marriage? The Case of the Ostend Company (1722–1731),” Tijdschrift voor sociale en eeconomische geschiedenis 12, no. 3 (2015), 57. We thank Elizabeth Cross for sharing the timeline of the Compagnie des Indes Orientales from her forthcoming book with us, and Holger Weiss for his guidance on the Ostindiska Companiet.

Notes: Table 1 was created to the best of our abilities on the basis of the secondary literature and some primary documents. For some companies, we were unable to find concrete answers for all categories, and this table would benefit from further fine-tuning by specialists on these companies. Currently, however, no similar quick overview of these joint-stock companies exists, and the table in its current form is suitable to illustrate our larger point about the different outcomes of the major companies operating the Asian trades and those in the Atlantic trade. Companies indicated with an * operated both in the Asia trade and in the Atlantic trade. Companies indicated with + went through several iterations, being revived several times throughout their existence. Companies indicated with ⇑ were absolved by other subsequent companies. Companies indicated with ⇓ absorbed other smaller companies. Note that while the Oostendse Compagnie had monopoly rights to trade in the West Indies and African coast as well, in practice it only operated in the Asia trade. Note that the Danish Asiatic Kompagni lost most of its monopoly rights to the Asia trade in 1772 when its charter was renewed, but that it was able to hold on to its trading rights in China. See Feldbæk, “Danish Trading Companies,” 208.

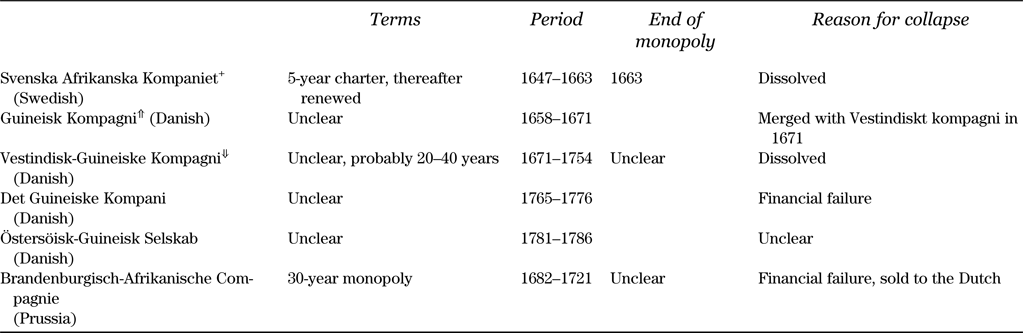

Table 2 Major Early Modern Joint-Stock Companies with Monopolies in the African Trade

Sources: For the WIC, see Phillips and Sharman, Outsourcing Empire, 69–80; Brandon, War, Capital, and the Dutch State, 112. For the RAC, see K. G. Davies, The Royal African Company (London, 1957). For the Compagnie du Sénégal and Compagnie de Guinée, see Stein, French Slave Trade, 11–14.

Notes: Companies indicated with an * operated both in the Asia trade and in the Atlantic trade. Companies indicated with + went through several iterations, being revived several times throughout their existence. Companies indicated with ⇑ were absolved by other subsequent companies. Companies indicated with ⇓ absorbed other smaller companies. The first and third iterations of the Compagnie des Indes did not focus on the Atlantic trade, and had monopolies that pertained to the Asia trade. Note that the monopoly rights of the WIC became narrower over time, including only the African trade and slave trade after 1674. These trades were opened to private traders in 1730 and 1734.

Sources: For the Svenska Afrikanska Kompaniet, see Niels Kastfelt, “Swedish Trade with West Africa (book review),” The Journal of African History 32, no. 2 (1991): 341–342. For the various iterations of the Danish companies, see Dan H. Andersen, “Denmark–Norway, Africa, and the Caribbean, 1660–1917: Modernisation Dinanced by Slaves and Sugar,” in A Deus ex Machina Revisited: Atlantic Colonial Trade and European Economic Development, ed. Pieter C. Emmer, Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau, and Jessica V. Roitman (Leiden, 2006); Erik Gøbel, The Danish Slave Trade and Its Abolition (Leiden, 2016). We are especially indebted to Holger Weiss for his guidance on the Danish companies.

Notes: Companies indicated with an * operated both in the Asia trade and in the Atlantic trade. Companies indicated with + went through several iterations, being revived several times throughout their existence. Companies indicated with ⇑ were absolved by other subsequent companies. Companies indicated with ⇓ absorbed other smaller companies.

Table 2 highlights the relatively short-lived nature of most of the corporations operating in the African trade during the early modern era, despite being granted generous monopoly terms. Trading in Africa posed a number of fixed and dynamic challenges to state-backed corporations. In terms of structural challenges, the closer geographical proximity of the African continent to Europe meant that shorter sailing times made it easier for interlopers to enter the African trade.Footnote 26 Additionally, the harsh disease climate in Africa likely meant higher mortality rates for Europeans (as compared to in Asia), and therefore greater turnover rates among company personnel on the West African coast.Footnote 27 Finally, the African trade, and the transatlantic slave trade in particular, brought with it specific pressures for monopolistic corporations that the Asian trade did not entail.Footnote 28 By the late seventeenth century, the booming European demand for sugar created a parallel demand for captive labor from Africa. In European cities, there was also a growing sense that the slave trade was a way to generate wealth.Footnote 29 These market pressures translated into political pressures as colonists in the West Indies, domestic consumers, and would-be private traders all appealed to the state for policies that would favor them.Footnote 30 Being the first to lose its monopoly, the RAC found itself at the center of this turbulent commercial and political landscape.

The RAC and the Principal-Agent Problem

Founded in 1672, the Royal African Company came into being at a fortuitous moment. By the late 1660s, its predecessor, the Company of Royal Adventurers, had become a shell of its former self.Footnote 31 Hurt by the Second Dutch-Anglo War (1665–1667) and the growing non-payment of subscriptions, the Company of Royal Adventurers resorted to desperate strategies, granting licenses to private individuals and leasing out part of its monopoly to a separate company, the Gambia Adventurers. Unable to meet its financial obligations, the company faced increasing pressure from its creditors, and dissolved. Eager to revive the African trade, the Crown granted the Royal African Company a new monopoly charter in 1672. With two hundred subscribers and a capitalization of £111,100, the Royal African Company bought up the assets of the Royal Adventurers.Footnote 32 According to Davies, both the contemporary state of international affairs and England's domestic economic conditions created favorable conditions for a relaunch. A series of French–Dutch wars in the 1670s distracted the company's foreign competitors, while regulations at home mandating lower maximum rates on interest-bearing investments made the company a relatively more attractive opportunity for investors. The support of the Crown also buoyed the new company, granting it a thousand-year monopoly. As indicated by Table 2, the horizon of the RAC's monopoly was especially long when compared to its rivals. Davies has argued that the English government was eager to place African trade on strong footing, warily eyeing competition from the French and especially the Dutch on the West African coast.Footnote 33

While the RAC charter granted it a monopoly in all aspects of the African trade, such as pepper, ivory, and gold, the company was specifically designed with the slave trade in mind.Footnote 34 The organizational and physical infrastructure of the company was spread over three continents. The seat of the company was located in England, where a series of committees, each with a specific domain (e.g., Committee of Shipping, Committee of Goods), were charged with executing day-to-day operations and gathering information from Africa and the West Indies. A central task of the committees was to report regularly to the company's supervising body, the Court of Assistants. With twenty-four members, the Court of Assistants decided on personnel, authorized expenditures, lobbied and petitioned Parliament, and had a final say in company operations. In essence, the RAC's governing body operated as an early-modern form of board of directors, and was remarkably engaged and efficient considering its size, according to Davies.Footnote 35

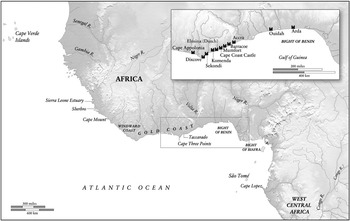

On the West African coast, the company operated through a series of fifteen to twenty forts (Figure 2), headquartered at James Fort in Gambia and at Cape Coast Castle in modern-day Ghana. The forts served to stockpile goods, house personnel, defend against other Europeans, and hold captives to load on transatlantic slave voyages.Footnote 36 The RAC forts were governed by English factors, who generally served in Africa on fixed terms. The fort factors oversaw trade on the coast and communicated regularly with London about trading conditions, supplies of trade goods, ship movements, personnel issues, relationships with local African states and societies, and foreign competition.Footnote 37 Additionally, the company employed a range of supporting personnel to keep its forts operational, such as carpenters, blacksmiths, clerks, warehouse keepers, soldiers, cooks, and doctors, some of whom were European, some free African workers, and some enslaved Africans. In the West Indies, the company's administrative apparatus was much thinner. The RAC sold some enslaved people to company agents stationed in places like Barbados or Antigua and sold others to private merchants, or to contractors who had previously agreed to purchase a certain number of captives from a given ship.Footnote 38 Finally, slave-ship captains moved between these fixed locations, bringing goods, letters, and supplies down to Africa; transporting captives across the ocean; and remitting sugar, coffee, other colonial goods, and information back to Europe.

Figure 2. Map of RAC forts. (Sources: David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade [New Haven, 2010], maps 5–6, and 59–62; Anne Ruderman, Mark Heller, and Harry Xuo, Current Research in Digital History 2 [2019], accessed 24 Apr. 2023, https://doi.org/10.31835/crdh.2019.10.)

Like all early modern long-distance trading corporations, the Royal African Company had to contend with principal-agent problems, even as it held monopoly privileges over the African trade.Footnote 39 On the West African coast, the company operated in a particularly challenging environment, facing competition from rival nations and interlopers for similar sources of captives and commodities. Fort personnel in West Africa faced the combined challenges of social isolation, disease, and the uncertainties of working with domestic traders and brokers. The company tried to assure loyalty from its top employees by paying salaries that reflected a risk premium and initially allowing them to conduct private trade on the side.Footnote 40 Additionally, the RAC required its top factors to post bonds, which were essentially the equivalent of a rental deposit for employment—factors got their money back when they demonstrated good behavior.Footnote 41 This strategy served as a selection mechanism as well, as only people of a certain socio-economic standing could afford to post such sums.Footnote 42 Over time, the RAC became aware of exorbitant death rates in West Africa, which created high turnover, desertion, and a sense of entitlement among the factors, who felt they were risking their well-being for the company.Footnote 43 While the company tried to appease its personnel by making some adjustments to its pay scale, service in Africa was never a great opportunity to make a fortune, and the company's principal-agent problem in Africa remained a delicate one.Footnote 44

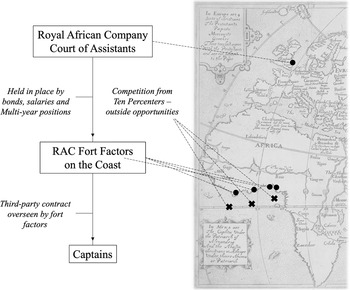

Unlike factors, captains were not direct employees of the company. Rather, the RAC leased slave ships and hired captains from other merchants whom the company referred to as the captains’ “owners.”Footnote 45 As hired hands, RAC captains did not post bonds or have long-term contracts that would tie them and their loyalty to the company. In maneuvering around the Atlantic World, slave-ship captains could cheat in a variety of ways. They could falsely report captives dead and sell them privately in the West Indies for their own gain. Likewise, captains could embezzle company goods, either by inaccurately reporting slave prices or by deceptively claiming that trade goods had been damaged, and pocketing the difference. Faced with these potential threats, the company had multiple ways of imposing checks on the captain. In the first place, the RAC management could search ships directly upon departure or arrival.Footnote 46 Moreover, the company's operational hierarchy placed the slave-ship captains that the company leased below the factors that it directly appointed (Figure 3). This structure made RAC factors responsible for overseeing captains on all slave voyages sent to company forts. Factors were in charge of inspecting trade goods and delivering captains’ enslaved people in return.Footnote 47 Additionally, the RAC required surgeons aboard slave ships to certify dead captives and submit their report to factors in the West Indies in order to receive their bonuses, a measure designed to prevent captains from claiming that captives had died and then selling them.Footnote 48 For slave voyages that did not stop at any of the forts, the company generally required captains to keep a so-called barter book, logging each transaction. Finally, the fact that captains were short-term employees of the RAC operated as a structural check, allowing the company to simply stop working with captains it did not trust.

Figure 3. Illustration of Royal African Company's original principal-agent structure and the disruption caused by the end of the monopoly. (Sources: Atlas Christianographie [London, 1636] from The Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection, La Jolla (CA). Digital version obtained via Stanford University, https://exhibits.stanford.edu/ruderman/catalog/qh094mc1741.)

While the company's various solutions to its principal-agent problems in the monopoly era were far from perfect, the sudden revocation of the Royal African Company's trading monopoly through the “Ten Percent Act” in 1698 destabilized the company's carefully crafted equilibrium.Footnote 49 In exchange for a 10 percent duty on the export of goods to Africa, the Ten Percent Act held that any English merchant wanting to participate in the slave trade now had parliamentary approval to do so. This new regulatory regime resulted in an immediate expansion of the English slave trade (see Figure 1), more than tripling the number of English ships, and leading to a 154 percent increase in the number of enslaved Africans that were forced across the Middle Passage.Footnote 50

For RAC, the Ten Percent Act not only posed a threat by directly increasing competition, but also by exacerbating the principal-agent problem that the company faced on the West African coast. Where the increased competition from private traders has been amply documented in the literature, the implications for the company's principal-agent problems on the African coast have received scant attention.Footnote 51 As illustrated in Figure 3, the Royal African Company's principal-agent problem increased overnight in scope and severity. Company factors had many more opportunities to cheat, as they could now collude with the so-called Ten Percenters, selling them enslaved people, exchanging goods with them, or supplying them with intelligence. Even though the RAC had to contend with some illicit trade during the monopoly period, the massive influx of legitimate competitors made each instance of cheating on the part of factors now more costly for the company: Where cheating under the monopoly mostly just hurt the company, cheating in the post-monopoly era both harmed the company and boosted its competitors, who were now free to conduct their trade in the open.

Focusing on the company's altered principal-agent problem raises new questions about the RAC's post-monopoly era path. Classic narratives of the Royal African Company have construed the company's post-monopoly failure as basically inevitable, albeit debating its primary cause. Davies's account of the RAC attributed the company's failure to its fundamentally flawed business model: unable to secure enough profits for its shareholders.Footnote 52 Likewise, Tim Keirn casts the RAC as doomed from the start, due to its indebtedness and the difficulties in recovering profits from the Americas.Footnote 53 Where Davies saw the 1688 Revolution and the wars of the 1690s as accelerating a decline that was inevitable, Pettigrew constructs a political argument, pointing to the regime change of 1688, rather than the economic structure of the company, as a decisive moment for the RAC's ultimate fate.Footnote 54 Carlos and Kruse also argued against an intrinsically flawed business model for the company, and emphasize instead how the RAC's loss of their charter rights made it impossible for the company to keep its market share.Footnote 55 Matthew Mitchell also points to the 1688 political changes as decisive for the company, and notes that in the monopoly era, the RAC outperformed its Dutch counterpart.Footnote 56 Whatever the cause, the general consensus remains that the company was doomed after it lost royal support, which led to the revocation of its monopoly a decade later.

The strong focus on RAC's ultimate failure has largely sidelined questions about the company's response to the enormous institutional shock it faced. While the failure of the RAC is certainly a question of historical interest, the company's behavior in the immediate post-monopoly era deserves equal scrutiny; not the least because of the window it can provide us into the adaptive abilities of early modern corporations. The revocation of the RAC's monopoly in particular was a major shock in corporate history, and inaugurated a new era in the transatlantic slave trade. How did the company try to adapt to this newly competitive world? More specifically, how did the company respond to the altered principal-agent problems it encountered? Our rare source base can shed light on the resilience of the company and on its ability to react rapidly to the change in its environment.

Evidence from Letters of Instruction to RAC Captains

The Royal African Company archives in the T70 series at The National Archives in Kew contain a range of records about the company, including a series of letters with instructions that the company issued to slave-ship captains before they departed from England. While some letters that the company received from agents on the coast are abstracted or excerpted in the RAC archives, the letters that the company issued to its captains appear in full form, specifying every command that was issued in the letter (for an example of a letter, see appendix Figure A.1.1).Footnote 57 These instructions are bound in three volumes and appear sequentially in the order in which they were written, starting in 1685.Footnote 58 We have photographed and transcribed all 292 letters and 70 postscripts that the company issued its captains between 1686 and 1706.Footnote 59

Table 3 presents an overview of the frequency of the types of letters with instructions to captains that the series contains. The three main types of instruction letters each correspond to a specific type of voyage that a given captain undertook: (1) slave voyages that stopped at a company fort in West Africa (for-slave); (2) slave voyages that traded outside the RAC fort structure, either in the Bight of Biafra or in West Central Africa (non-fort-slave); and (3) messenger ships, which traveled from England to the company's forts in Africa and then returned home. Finally, a miscellaneous category of Other contains a few letters that were written to factors or that concern the sugar trade. Additionally, the series includes a number of separately entered postscripts, which we analyzed in conjunction with the main letter they belong to. Appendix Table A.1 provides a detailed overview of the types of letter by unique ID. The final column of Table 3 provides an indication of the completeness of the series of letters, by presenting them as the share of total RAC voyages listed in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Covering about 83 percent of the RAC voyages reported in TASTD, we are confident that this set of instructions comprehensively covers a central node of company–captain communication during the period just before and just after the revocation of the company's monopoly of the African trade.

Table 3 Overview of RAC Letters with Instructions to Captains by Type and Year

Sources: Royal African Company records, T70/61–63, TNA; and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.

Notes: Letters that were written in the calendar year before the earliest calendar year listing in the TASTD (departure year) are counted in this table according to the TASTD calendar year. For the year 1686, we omitted voyages listed in the TASTD that arrived in the Americas before September 1686, as we were worried the corresponding letter was written in 1685 (and for which we only have one entry). We also omitted all RAC voyages listed in the TASTD that departed from the Americas (as these ship captains would not have received a letter from the London office before departure) or ones for which no information—not even imputed values—for port of departure were available.

For the purposes of this paper, we are especially interested in the first subset (the fort-slave letters) because these letters show the ways the captain and company fort factors interacted both during and after the monopoly era. While the fort-slave letters are not a direct copy of one another, there is a high degree of similarity between them. At the structural level, the letters tend to cover the same topics that were relevant for the type of journey at hand: instructions on how to manage the crew, instructions on how to treat captives, instructions on destinations to stop at, and so on. At the paragraph and even sentence level, it is not uncommon for phrases or clusters of phrases to repeat themselves across multiple (or even most) letters, albeit with some minor deviations.

It is exactly this repetition and the variation in repetition that makes this corpus of letters such a valuable and rare source base. The formulaic nature of these letters allows us not only to track changes in company policy, both big and small, over time, but also at relatively high frequency intervals. In fact, this corpus might be one of the few historical sources from early modern corporations to offer such a detailed and structured look into the evolution of company policy. This window is especially valuable because it covers a period in which this major early modern corporation experienced an existential crisis, allowing us to answer questions about the company's response to a major shock: the end of its monopoly.

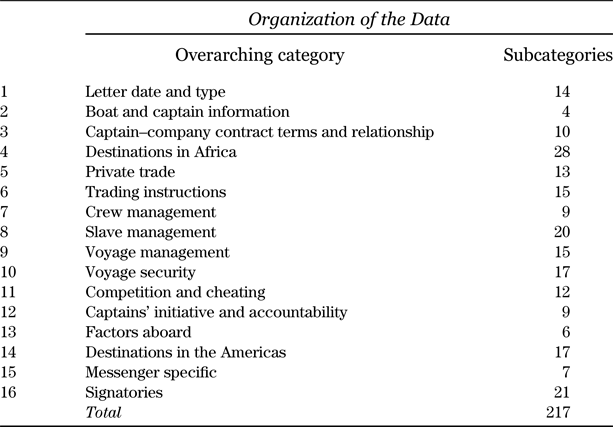

To exploit the formulaic nature of the letters, we coded each instruction letter, turning this qualitative source into data. We created separate variables for the vast majority of singular commands that recurred in the letters.Footnote 60 We then grouped these variables into overarching categories corresponding to specific domains of the voyage or the captain–company relationship. Table 4 presents the structure of our database, listing each overarching category and the number of variables belonging to it. In total, our database includes 217 variables, of which 178 are direct instructions to the captain.Footnote 61 Further details about the overarching categories, the variables, and our data construction principles can be found in our online Appendix.

Table 4 Structure of the Dataset

Sources: Royal African Company records, T70/61–63, TNA.

Changes in the commands included in the letters reflect shifts in the company's priorities and give us insights into its evolving strategy in the slave trade. For example, over time, the company officials in London issued additional instructions to the captains carrying out their orders. The excerpts from two letters below illustrate how the company tweaked its orders in the course of the 1690s, adding instructions to pick up corn and canoes on the Gold Coast before heading to the Bight of Benin (variable 9.3).Footnote 62

Being dispatched our Castle you are to proceed to the coast of Whida or Arda and there use your uttmost endeavour for the procureing your complement of six hundred negroes as by Charterparty, which we expect you doe with all the Good husbandry you can for our advantage, And if our factors on the said Coast can further your dispatch that you negotiate with them as directed in your Charterparty. . .Footnote 63

Being dispatched our Castle you are to proceed to take in your Corn & Canoes, thence to the Coast of Widah or Arda and there use your uttmost endeavour for procureing your complement of 550 negroes as by Charterparty, which we expect you do with all the good husbandry you can for our advantage, and if our factors on the said Coast can further your dispatch that you negotiate with them, as directed in your Charterparty.Footnote 64

Table 5 shows this pattern of adding additional commands on a more aggregate level for the overarching category of slave management. While the earlier letters contained only four different types of instructions to manage captives, by the early 1700s, the range of commands targeting slave management practices had increased to fifteen. Many of these later commands were geared to keeping enslaved people healthy for sale in the West Indies. The company introduced similar modifications in other domains as well, such as crew and voyage management and trading instructions. For instance, over time, the company added provisions to receive commodities from factors on the Africa coast (e.g. variable 6.8), to prevent waste of company supplies (variables 7.6 and 7.7), and to write home when possible (variable 11.11) Some of these news measures were a direct response to incidents that had taken place. For example, following the disastrous voyage of the Warrington in 1699, the company consistently instructed captains to “take especiall care” with their ship's gunpowder in order to “prevent such great misfortune both to ship and men as hath happened to the Warrington w[hi]ch was blown up by her powder taking fire.”Footnote 65

Table 5 First Appearance and Total Occurrence of Slave Management Commands

Sources: Royal African Company records, T70/61-63, TNA.

Notes: Dummy variables indicated with an *are so-called umbrella categories. An umbrella category means that additional, and more specific instructions in this area were added over time, and which are dummy variables on their own right in the database. Note that the umbrella category can have a value of 1, while the related more specific variables can be 0. Conversely, however, it cannot be the case that the specific variables have a value of 1, while the umbrella category would be 0, as the umbrella is an indication of any instruction related to this domain. For the category “oversee selection of slaves,” further specifications with selection criteria regarding the age, gender, and health of the to-be-purchased enslaved people were added in 1687. For the category “muster slaves” (a roll-call, or census aboard), a specification to the condition of the slaves was added in 1688.

While the scope of instructions grew over the period of our analysis, the company did not necessarily keep all the instructions it added. For example, the company adopted the practice of purchasing enslaved people on the Gold Coast, so-called guardian slaves, to oversee captives from the Bight of Benin in 1687, only to abandon this measure by 1693 (variable 8.9).Footnote 66 In a similar vein, the company experimented with ways to improve trading conditions on the African coast. Between 1693 and 1701, the RAC repeatedly instructed its captains to “make the best observation” possible about opportunities for trade in Africa, and to “bring us samples of any such plants graines or other curiosities as you may meet with” (variable 12.2); aiming to see what could be grown on the coast.Footnote 67 Whether the disappearance of these commands in the early eighteenth century reflect changing priorities of the company or the efforts were futile remains unclear. Nonetheless, the systematic start-and-stop pattern of certain instructions indicates that company was willing both to add and eliminate practices based on experience and changing priorities.

The adaptive nature of the company is visible in changes in instructions that focused on the security of the voyage as well. Like all early modern state-sponsored companies that engaged in overseas trade, the Royal African Company operated in a turbulent world. European countries repeatedly waged war with one another, and attacks on merchant vessels were an integral component of maritime warfare. While expressions of caution about their French rivals recurred in the letters throughout the period under consideration, and Figure 4 shows that the RAC temporarily gave its letters a more aggressive tone during the most intense period of the Nine Years War (1689–1697), instructing its captains to seize French vessels.

Figure 4. Share of letters that contain a command to beware of the French or to seize the French (1685–1706). (Source: Royal African Company records, T70/61-63, TNA.)

In sum, the fine-grained nature of our coded letters give us a new vantage point into this early modern corporation. While the company relied on a formula to instruct its captains, the fact that the formula evolved over time illustrates that RAC was not a rigid organization stuck on a single model. Although there was a natural time-lag due to the pace with which information could physically travel, once news reached the company in London, it swiftly updated its strategies. As the company acquired knowledge and experience from the African coast, it incorporated these lessons into its management practices. Additionally, the instruction letters provide evidence that the company not only learned by doing, but they also reveal that the RAC responded quickly to changing international circumstances.

Instructions to Captains and the Monopoly Shock

Our dataset also allows us to assess the company's response to the biggest external shock it faced: the loss of its monopoly on June 24, 1698.Footnote 68 While the RAC faced principal-agent problems throughout its existence, the end of the company's monopoly created unprecedented opportunities for its agents in West Africa to cheat. The company lost no time responding to this potential threat. In September 1698, the RAC first sent Joseph Baggs on a messenger ship to all of its key forts along the West African coast, instructing him to “make full observa[ti]on of the behaviour of our factors,” and especially to discern “whether they attend our concerns only or joyn with or assist private traders.”Footnote 69 Following Baggs's West African tour of company forts, the RAC in December 1699 sent Josiah Daniel, whom it had previously employed as a captain, to serve as a sort of crisis manager. The company instructed Daniel to go Cape Coast Castle to consult with the company's three chief factors and meet with the head of the Dutch WIC in order to formulate a joint company strategy against interloping ships. The end of the company's monopoly in 1698 had unleased a newly competitive world, and company management in London was fully aware of it.

Having an extraordinary opinion of your good judgment and fidelity, wee do appoint that dureing your aboad at Caboe Corso Castle you apply your self to our chiefs there and be of councill with them; wee have given them order to admitt you, and so often as you meet let all your resolu[ti]ons be entred down in writing and signed by the factory, copie whereof do you deliver to us at your return.

Wee order that dureing your stay there, the Dutch General of the Mine be sent to, and that a consulta[ti]on may be appointed for the better improvement of the trade to the benefit of both companies; and that you acquaint him with the orders this compa[ny] gives both to their forts and ships relating to interlopers of their nation.Footnote 70

But the company quickly instituted a structural shift as well. The Royal African Company was able to swiftly respond to the exacerbated principal-agent problem it faced with the end of its monopoly because the very infrastructure of the transatlantic slave trade gave the company a real-time monitoring mechanism: slave-ship captains. Unlike the Hudson's Bay Company, the Royal African Company did not have to rely on account books or other forms of second-hand knowledge to detect cheating. Rather, the company's slave-ship captains who were already going to the West African coast to purchase enslaved people, could double as monitors, reporting on the behavior of fort agents to authorities at home.

While instructions intended to check the captain's opportunities to cheat appear throughout the entire period analyzed, the company started commanding captains to check on factors only after the loss of its monopoly privileges. Starting in June 1700, the instruction letters came to include new stock phrases that ordered the captain to check on the factors; an instruction that swiftly became more explicit and urgent in language:

[I]f you observe any of the companies factors or servants negligent in theire duty to us or acting contrary to the intrest of the compa[ny] by assisting or trading w[i]th the 10 Percentmen, Dutch Interlopers or any other advise us thereof… .Footnote 71

You are hereby ordered to make the strictest observat[io]n you can concerning the comp[any’]s factors and serv[ant]s upon the coast and according as you find them negligent or acting anything contrary to the compa[ny’]s interest; especially if they do protect or in the least assist the interlopers of any other nation whatsoever, also if they trade with or lade any goods or gold upon English ships or others that are not in our service, you must enter a particular account thereof in writing and deliver the same to us at your return be very exact therein, that upon occasion you may attest the same upon oath.Footnote 72

Figure 5 shows the prevalence of the main check on the captain (the certification of dead slaves by the surgeon) and the main check on the factor (captain monitor the factors’ behavior) in the instructions letters for each year. Although the company had implemented measures to control for the captain cheating from the beginning of our dataset in the 1680s, it only added measures to prevent factors from cheating with the end of its monopoly in 1698.

Figure 5. Share of letters in each year that contain a command to monitor the factors in West Africa, 1685–1706. Notes: The “checks on the factor” variable is based on the command in our database that directly asks the captain to do so (Category 11.4). For the standard command that imposes a check on the captain, see variable 13.4. (Sources: Royal African Company records, T70/61–63 series, TNA.)

This sudden discontinuity in monitoring priorities led to a changing hierarchy between captains and factors after the end of the monopoly. As illustrated in Figure 6, in using slave-ship captains to monitor the fort factors, the Royal African Company altered it original organizational structure (see Figure 3). Following the end of the monopoly, the RAC granted its captains the authority to surveil factors instead of simply being subject to their orders. This organizational shift placed captains in a new position of critical importance to the overall company operation.

Figure 6. Illustration of the Royal African Company's postmonopoly principal-agent structure. (Source: Atlas Christianographie [London, 1636] from The Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection.)

The changing reliance on the captain went well beyond trying to prevent its fort factors from cheating. In the aftermath of 1698, the company also began to depend on its captains to accomplish more complex tasks related to maintaining the RAC's competitive edge. Here the RAC took advantage less of the infrastructure of the transatlantic slave trade itself and more of the dynamism of ship trade. Unlike fort factors, slave-ship captains were not stuck at particular places on the West African coast and could more easily maneuver about, thereby giving the company a better sense of the overall competitive landscape. Only a few months after the Ten Percent Act had taken effect, the company updated its letters with new instructions that asked the captain to use his judgment to further the company's interest on the West African coast. These new instructions included, for example, requests for the captain to put together information on its competitors and to act in the company's best interest in any situation that the instructions did not explicitly cover:

You must bring no returns from the coast, but such as you have orders for in writing from our factors, and not to deliver the same but by order in writing from us, and where any thing is omitted in your instructions, you must alwayes observe to act what is most intirely for the benefit of this joynt stock and take care that all persons under you do the same. (Variable 3.11)Footnote 73

You are also to advise us by all oppertunities what ships you meet w[i]th or hear of trading on the Coast, wherein advise the masters name, the ships burthen and (as near as you can) their Cargoes, with what slaves they carry off the Coast. (Variable 11.6)Footnote 74

Many of these new types of instructions were formulated in an open-ended manner, and stand in contrast to the highly specific commands of the letters that the company had previously issued. In newly relying on its captains’ initiative and discretion, the Royal African Company thus significantly expanded the responsibilities of captains and its dependence upon them.Footnote 75

Figure 7 shows this transition in quantitative terms. For each letter we used the prevalence of specific commands to compute a “score” on two dimensions of the captain's role: (1) a score that reflects his perceived trustworthiness (by the company); (2) a score that reflects the company's desire for the captain to take initiative beyond the regular aspects of the job. We then added the captain's trustworthiness and initiative scores to create an overall reliability score. The enormous uptake in the reliability score after 1698 demonstrates the company's growing dependence on the captain in the post-monopoly era. Both the captain's new monitoring role and the increased reliance on him for matters that required trust and initiative were thus an integral part of the measures that the RAC took secure and enhance its competitive position after the loss of its trading privileges.

Figure 7. “Captain's score” for trustworthiness, initiative, and overall reliability. Notes: The score was computed as follows. For each year and variable, we calculated the share of letters that contained the variable of interest. For example, for a year in which we had four letters, and one of those letters contained the variable of interest, the score for that year and that variable would be 0.25. We then added the scores for all variables for that year. Variables that reflect a high degree of trust between the company include the company directly expressing trust in the captain, or giving tasks to the captain where possible captain–outsider collusion could occur. Variables that reflect special initiative concern variables that go beyond the regular duties of the captain and for which the captain needs to use his own judgment. Captain trust score includes instruction categories 3.3, 3.4, 3.8, 3.11, 7.6/7.7 (a positive value for either one), 7.9, 11.4, 11.5, 11.9, and 11.10. Captain initiative score includes categories 8.10, 8.16, 11.6–11.8, and 12.1–12.3. Captain reliability score includes all categories. One concern that should be addressed is the risk of artificially inflating the captain reliability score by counting separately the commands that always occur in pairs. We believe that we have minimized this risk by selecting categories that are different enough from each other (and appear in different sections of the letter), and by explicitly excluding umbrella categories. (Source: Royal African Company records, T70/61–63, TNA.)

Running to Stand Still

The revocation of the RAC monopoly was one of the most dramatic reversals in the history of the corporation. Overnight, the corporation faced a new competitive landscape and a worsened principal-agent problem with its fort factors on the West African coast. Our paper has used a newly constructed dataset of instructions that were issued to Royal African Company slave-ship captains to examine how the company adapted to this first order shock. We have shown that the company took advantage of the maritime infrastructure of the slave trade, with ships continually sailing between Europe, Africa, and the Americas, and it quickly pivoted to using its captains as a way to monitor its factors in Africa. In doing so, the company reversed its traditional hierarchies on the coast, suddenly giving captains oversight over factors. Additionally, the company started to rely on its captains as a source of information about its competitors. As they could maneuver about the coast, slave-ship captains were poised to inform company officials in London about the competitive landscape in West Africa. More generally, the company increasingly came to embrace a strategy that rested on the initiative of its captains.

The fine-grained picture of the RAC's management's decisions as reflected through the instruction letters challenge some long-held interpretations of the company. Generations of historians have approached the company's rise and fall in terms of its ultimate fate, seeking to explain its failure. However, when using the end of the story as the starting point for questions—as valid as they may be—we run the risk of missing the non-linear nature of the path leading up to that point. The end of the RAC's monopoly undoubtedly contributed to its ultimate demise, but this outcome was far from clear at the end of the seventeenth century. While we can only see the company's perspective and cannot measure how effective its new instructions to its captains were, we have shown that the company fought hard to maintain its position and compete with private traders right after the Ten Percent Act, rapidly innovating to meet new challenges. By analyzing the immediate post-monopoly period, we find that the RAC was in fact running to stand still.

We were able to bring this hidden dynamism of the RAC to light through exploiting a non-conventional body of sources. Such perspectives on quotidian operations of early modern corporations tend to be rare, either because systematic records are hard to come by, or because of a lack of quantitative approaches to qualitative records. While studies of the transatlantic slave trade have been anchored in quantitative methods for decades, the focus of this work has been on already quantified aspects of trade, such as the number of ships and enslaved people, prices, and mortality rates. Our data-driven approach to the entrepreneurial side of the trade, gives new insights into the ways in which corporations shaped the trade, and were shaped by it in turn.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material (appendix and database) for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680523000351.