Introduction

Twine and rope making were surely common activities in prehistoric times. However, as both perishable materials and the actions to create them are nearly invisible in the archaeological record, tracing their origins in time is a challenge. Most of the crafted objects and materials made of plant fibres (bags and baskets, hunting and fishing gear—e.g. fishing lines and nets, bowstrings—body adornments, textiles, etc.) are only preserved in the archaeological record under exceptional circumstances, and they are usually partial (for a list of known examples, see the next section). This paper seeks to summarize the evidence of rope manufacture and rope structures reported to date in prehistoric times in Europe while exploring the potential of rock art to illustrate what type of activities and practices were related to their use and the various roles of these perishable materials. In Spain, Levantine rock art (LRA), a rock-art tradition included in the World Heritage list in 1998 as the ‘largest group of rock art sites anywhere in Europe’ providing ‘an exceptional picture of human life in a critical phase of human development’ (UNESCO 2022), offers a unique window into the use of ropes in European prehistory. Surprisingly, though, while most of the scenes discussed in this paper have been well known for quite some time now, they have not been used to explore prehistoric rope technologies, uses and practices in detail. We noticed this gap during our recent study of a new LRA site (Barranco Gómez, Castellote, Teruel) (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Domingo and Angás2021) with a new honey-hunting scene illustrating the use of a rope-ladder to grasp a honeycomb. The scene is quite well preserved compared to other Levantine paintings and includes all kinds of details illustrating the climbing technique and the implements used by the climbers (Fig. 1). The singularity of the rope structure depicted prompted us to go beyond the literal reading of the action or the subject matter (honey-hunting scenes), as other researchers have done before (Baldellou et al. Reference Baldellou, Painaud, Calvo and Ayuso1993; Dams Reference Dams1983; Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924; Ribera et al. Reference Ribera, Galiana, Torregrosa and Llin1995; etc.) to explore the nature of the ropes and the climbing technologies of prehistoric societies as illustrated in their art. To do so, we conducted a literature review to identify any reference to the use of plant fibres and cordages in the known artistic record and their potential uses. In the literature on LRA these materials have been described as: lassos, identified in supposed domestication or hunting scenes (Beltrán Reference Beltrán1968, 51; Blasco Reference Blasco1975; Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1959; Jordá Reference Jordá1974, 218; Ruiz & Allepuz Reference Ruiz and Allepuz2011, 122; Viñas et al. Reference Viñas, Morote and Rubio2015) or hunting traps (Jordá & Alcácer Reference Jordá and Alcácer1951, 13; Blasco Reference Blasco1974, 43), textiles (Dams Reference Dams1984; Lillo Reference Lillo2014; Ortego Reference Ortego1976), ornaments (Beltrán Reference Beltrán1968, 43; Galiana Reference Galiana1985, 70; Jordá Reference Jordá1974, 219), bow-strings (Bea & Domingo Reference Domingo, Davidson and Nowell2021; Jordá Reference Jordá1974), basketry (Beltrán Reference Beltrán1968, 53), a sort of swing related to a childbirth scene (Domingo Reference Domingo2005, 189) or as ropes. The use of ropes, strings or cords by Levantine societies has been consistently suggested since the discovery of the first honey-hunting scenes (Beltrán Reference Beltrán1968; Breuil Reference Breuil1912, 551; Dams Reference Dams1978; Reference Dams1983; Reference Dams1984; Dams & Dams Reference Dams and Dams1977; Domingo Reference Domingo2005; Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1921, 65; Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924; Obermaier & Wernert Reference Obermaier and Wernert1919). This topic is of particular interest to this study, since based on the examples analysed in this paper it could be argued that prehistoric societies at the time not only mastered climbing but developed different strategies to ensure success and minimize risks.

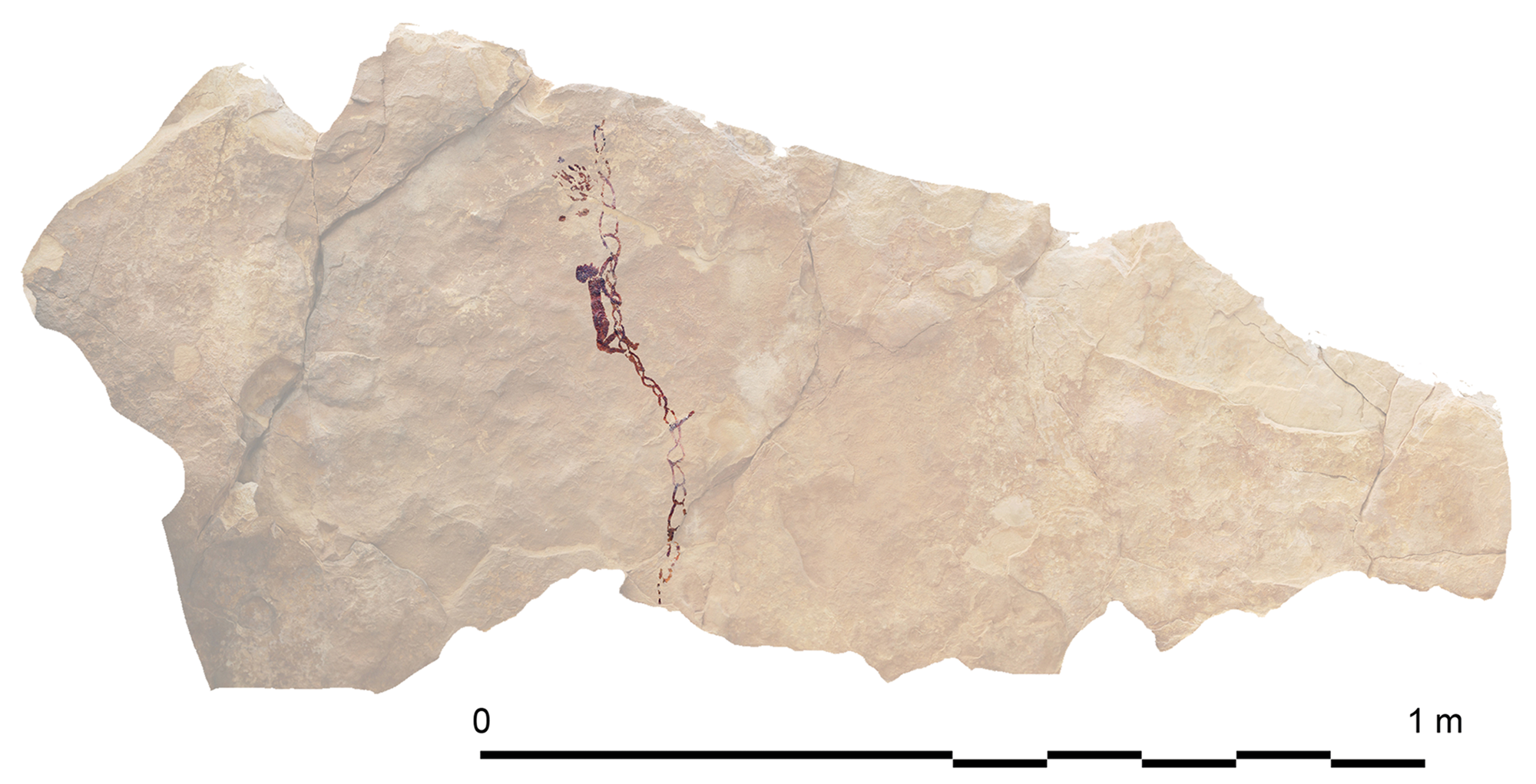

Figure 1. Climber in a honey-hunting scene in Barranco Gómez (after Bea et al. 2021).

In short, this paper explores the evidence so far known in the European archaeological record for the use of ropes in prehistoric times, as well as the evidence, potential uses and technologies LRA scenes suggest for these items. We also explore what Levantine narratives can tell us about climbing technologies and practices in prehistoric times.

Evidence of ropes in prehistory

Plait and twisted fibre have been defined as a complex technology using different components (K. Hardy Reference Hardy2008; Hurley Reference Hurley1979; Kenyon Reference Kenyon1951; Kvavadze et al. Reference Kvavadze, Bar-Yosef, Belfer-Cohen, Boaretto, Jakeli, Matskevich and Meshveliani2009; McKenna et al. Reference McKenna, Hearle and O'Hear2004; Small Reference Small2002) and even a mathematical comprehension of pairs, groups and numbers (B. Hardy et al. Reference Hardy, Moncel, Ferfant, Lebon, Bellot-Gurlet and Mélard2020). It is the technological basis for making textiles, bags, nets, mats and ropes. Nevertheless, although it is a basic component in all cultures, there is very little direct or indirect evidence in the archaeological record, and especially in the earliest phases of prehistory.

The use of ropes and complex production technologies (by twisting fibres) has already been documented among Neanderthals. At the Abri du Maras (France) site, some plaited fibre remains (three bundles of fibres twisted to form a rope) were stuck on a lithic tool (a Levallois flake) (B. Hardy et al. Reference Hardy, Moncel and Daujeard2013; Reference Hardy, Moncel, Ferfant, Lebon, Bellot-Gurlet and Mélard2020).

Ancient indirect examples are still scarce and geographically dispersed (Balme Reference Balme2011; Vanhaeren et al. Reference Vanhaeren, d'Errico, van Niekerk, Henshilwood and Erasmus2013). The earliest known date to the European Upper Palaeolithic. At Hohle Fels site (Germany) a piece of mammoth tusk has been described as an instrument for spinning plant fibres to make ropes or textiles (Conard & Malina Reference Conard and Malina2016). A similar use as an element for braiding fibres has been suggested for the Palaeolithic baton percé (generally dated to the Solutrean or Magdalenian periods) (Rigaud Reference Rigaud2001).

Other indirect evidence for twisted fibres, textile making, basketry and nets dating as early as 27,000 bp include clay imprints of textiles and cordage recovered at the Pavlov I site (Czech Republic) (Adovasio et al. Reference Adovasio, Soffer and Klíma1996; Soffer Reference Soffer2004; Soffer et al. Reference Soffer, Adovasio and Hyland2000, 524).

Probably the most spectacular among the indirect finds published so far are the fibre-like decorations (belts, hat, ornaments) identified on several female figurines from Kostenki I, Dolní Vestonice I, Lespugue (Adovasio et al. Reference Adovasio, Soffer and Page2007; Barandiarán Reference Barandiarán2006; Delporte Reference Delporte1979; Schebesch Reference Schebesch2013; Soffer et al. Reference Soffer, Adovasio and Hyland2000). Later in time, in an Epigravettian context, some of the engraved human motifs identified at Grotta de Addaura II have been interpreted as being tied with ropes (Blanc Reference Blanc1954; Bolzoni Reference Bolzoni1986; Budano Reference Budano2019; Mussi & Zampetti Reference Mussi, Zampetti, Grotta, Scuderi, Tusa and Vintaloro2004). Based on much of this indirect evidence, and considering the potential importance of string, twine and rope manufacture in prehistoric daily activities (including tying, carrying, transporting, storing, and so forth), Barber (Reference Barber1994) proposed the concept of ‘the string revolution’, denoting technological innovation and new ways to save labour with important implications for humans.

Direct evidence is even more rare. At Nerja cave (Spain) a 30 cm piece of rope was dated to 30,000 bp (J.L. Sanchidrián pers. comm. to MB, 30 November 2020). Another large calcified piece of rope recovered in ‘Sala de las Estrellas’ at Ardales cave was believed to have been used in prehistoric times to access a group of black hand stencils located in a 4 m drop (Cantalejo et al. Reference Cantalejo, Espejo, Ramos, Wenigerd, Ramos, Wenigerd, Cantalejo and Espejo2014, 133; Gutiérrez & Martín Lerma Reference Gutiérrez, Martín Lerma, Castelo and Rubio2014–15). However, recent direct dating of the rope has revealed that it was placed there in the sixteenth–seventeenth century, demonstrating how important it is to date this sort of evidence to confirm the age (Ramos-Muñoz et al. Reference Ramos-Muñoz, Cantalejo and Blumenröther2022). At Ohalo II (Israel) some remains have been dated to 19,000 years bp (Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Danin, Werker, Schick, Kislev and Stewart1994). A rope fragment was discovered by A. Glory at Lascaux cave (Bahn Reference Bahn1995, 194; Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1982; Leroi-Gourhan & Allain Reference Leroi-Gourhan and Allain1979, 183) dating to 18,000 years bp.

European Final Palaeolithic and Mesolithic finds (Douglas Reference Douglas1991, 220; Zhilin Reference Zhilin, Longo and Skakun2008; Reference Zhilin2014) include those from Santa Maira (Spain) (12,730–12,710 cal. bp) related to the Epipalaeolithic occupations (Aura et al. Reference Aura, Carrión, Estrelles and Pérez2005, Reference Aura, Pérez, Carrión, Seguí, Jordá, Miret and Verdasco2020), or the fishing net from Antrea (Finland) (9140±135 bp) (Miettinen et al. Reference Miettinen, Sarmaja-Korjonen and Sonninen2008). From the Neolithic onwards, there are more indirect (clay imprints) and direct (bags, sandals, cordages and baskets) evidence, with examples at La Draga (Piqué et al. Reference Piqué, Romero, Palomo, Tarrús, Terradas and Bogdanovic2018), Los Murciélagos (Alfaro Reference Alfaro1980; Buxó Reference Buxó, Bakels, Fennema, Out and Vermeeren2010; Cacho et al. Reference Cacho, Papí, Sánchez-Barriga Fernández and Alonso1996) or Cova des Pas (Romero-Burgués et al. Reference Romero-Burgués, Piqué, Picornell, Calvo and Fullola2021). But how to deduce potential uses of ropes beyond fibre objects? LRA provides unique examples to illustrate a variety of uses in prehistoric times.

Levantine rock art and the use of ropes

LRA is a unique post-Palaeolithic artistic phenomenon in Europe, exclusive to the eastern side of the Iberian peninsula, with more than 1000 sites recorded so far. It is a naturalistic art with a strong narrative component, in which humans (men, women and even children) and their material culture (a quite diverse toolkit including bow, arrows, quivers, boomerangs and bags, as well as all sorts of ornaments, clothing, hair accessories, etc.) take part in dynamic scenes that today we describe as hunting, war, social performance or gatherings, among others. A limited number of animal species were also depicted. Bull, wild goat and deer are the most common, followed by wild boar and horse, while canids, birds or insects are almost incidental. The chronology and the cultural affiliation of the authors (whether hunter-gatherers or farmers) is a matter of debate, as reliable chronometric dating is lacking to date (Ochoa et al. Reference Ochoa, García-Díez, Domingo and Martins2021). Researchers place the origin either in relation to the end of art of Palaeolithic style (which in these region lasts until 11,700 cal. bp) (Román et al., Reference Román, Nadal, Domingo, García-Argüelles, Lloveras and Fullola2016) or to the Neolithic, with an origin between 7700 and 6800 cal. bp (Juan Cabanilles & Martí Reference Juan Cabanilles, Martí, Garcia-Puchol and Salazar-García2017). However, some kind of connection with the Neolithic is widely accepted (Bea & Domingo Reference Domingo, Davidson and Nowell2021; Domingo Reference Domingo2005; Reference Domingo, Domingo Sanz, Fiore and May2008; Reference Domingo, García, Collado and Nash2012; Hernández Reference Hernández, García, Collado and Nash2012; Martínez-Bea Reference Martínez-Bea2005; Reference Martínez-Bea2009; Mateo Reference Mateo2009; Reference Mateo, García, Collado and Nash2012; Utrilla & Martínez-Bea Reference Utrilla and Martínez-Bea2007; Reference Utrilla, Martínez-Bea, Soler, Pérez and Barciela2018; Villaverde et al. Reference Villaverde, Guillem and Martínez2006; Reference Villaverde, Martínez, Guillem, López, Domingo, García, Collado and Nash2012; Viñas Reference Viñas, García, Collado and Nash2012).

With only a few exceptions, the clearest examples showing the use of ropes or rope ladders in LRA are related to depictions of climbers and honey-hunting scenes (Mateo Reference Mateo1995). The only exception is a scene from Els Rossegadors site, in which an archer ties up an animal with a long rope. Nevertheless, the rope may well have been added later, given that figures in the scene differ in colour from each other, as suggested by Viñas et al. (Reference Viñas, Morote and Rubio2015, 113). Other examples of ropes listed in the literature are stylistically distant from the classical Levantine patterns: a scene from Muriecho site, showing a live deer capture, with a human carrying a long, rigid tool (stick) with a rounded end which has been interpreted as a lasso (Baldellou et al. Reference Baldellou, Ayuso, Painaud and Calvo2015; Utrilla & Martínez-Bea Reference Martínez-Bea2005), and those from Selva Pascuala and Doña Clotilde sites, in which quite schematic horses are tied with some sort of rope (Beltrán Reference Beltrán1968; Blasco Reference Blasco1974).

LRA provides the best visual evidence in Europe for the use of ropes and plant fibres and the practices related to them. It is therefore ideal for analysing this ‘missing majority’ (Hurcombe Reference Hurcombe2014), i.e. perishable materials that were probably dominant in quantitative terms, and yet barely known. It also illustrates an activity, climbing, which would be difficult to deduced from the analysis of archaeological deposits and the material remains preserved.

Climbing systems. Ropes and rope ladders

The catalogue of LRA includes hundreds of sites, but explicit representations of ropes or rope-ladders are rare (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Domingo and Angás2021). Some of the known examples cannot be linked to a specific activity, but most of them are related to climbing. Nevertheless, climbers do not only use ropes and rope ladders, but occasionally climb some type of plants, branches or trees. Climbers are either related to wild boar hunting, honey hunting or unidentifiable activities, as they are isolated or are part of incomplete scenes (see Table 1 for an updated list of climbers and scenes).

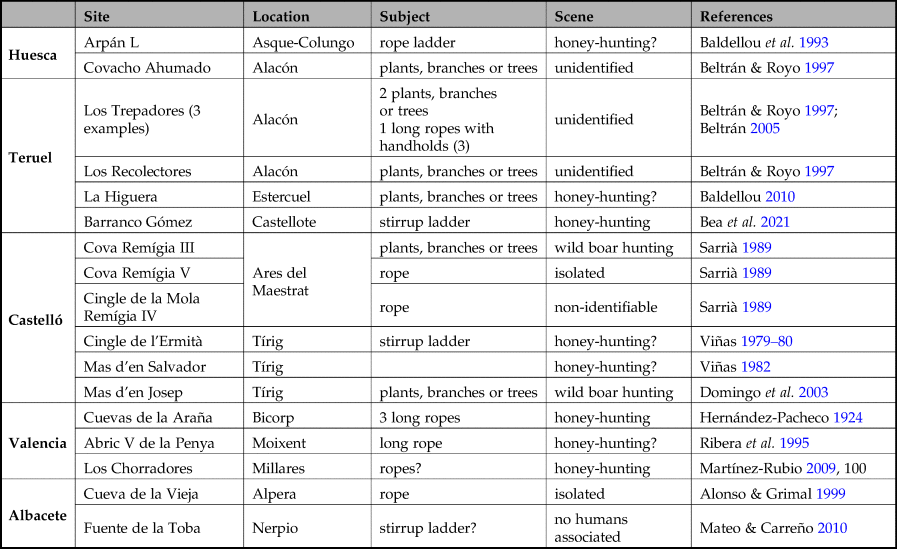

Table 1. Sites with an updated list of representations of climbers and type of scenes in which they appear.

Interestingly, the few examples known seem to be clustered together in two regions: the Maestrazgo to the north and the Caroig massif to the south (Fig. 2). Only one site, the Arpán shelter in the Vero river, escapes this distribution. And even if the surrounding area is home to a number of sites (such as the concentrations of sites of Lower Aragón, Albarracín and Serpis, upper Segura and Guadalquivir rivers), no reports have been made on the presence of climbing scenes in any of them. Such exclusive distribution may point to a territorial restriction of either this practice or the symbolic value given to it. While LRA has a wide distribution, certain themes such as this one are restricted to particular areas, reflecting some sort of territorial behaviour or code. Another well-known example is the distribution of wild boar depictions, which is restricted to the northern area (Domingo et al. Reference Domingo, López-Montalvo, Villaverde, Guillem and Martínez-Valle2003).

Figure 2. Distribution of climbing scenes in Levantine rock art. (1) Arpán; (2) Los Recolectores; (3) Los Trepadores; (4) Higuera de Estercuel; (5) Barranco Gómez; (6) Galería Alta; (7) Cingle de Mola Remígia; (8) Cova Remigía III–V; (9) Cingle de l'Ermitá; (10) Mas d'en Salvador; (11) Mas d'en Josep; (12) La Araña; (13) Cueva de la Vieja; (14) Abric de la Penya.

A literature review on the types of ropes depicted in LRA shows that Jordá (Reference Jordá1974, 219) analysed honey-hunting scenes and classified ropes and rope structures as ‘various tools’, together with other tools of unclear function or interpretation or produced with unknown raw materials. His group A includes depictions that he described as linear motifs either isolated or associated to humans, used for holding or hanging, with a subgroup 1 described as ropes.

Most studies do not describe different types, but just globally refer to ropes, trees/plants (branch like), masts (Baldellou Reference Baldellou2010; Beltrán Reference Beltrán1968; Reference Beltrán1982; Beltrán & Royo Reference Beltrán and Royo1997; Dams Reference Dams1984; Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1921) or simply ladders (Baldellou et al. Reference Baldellou, Painaud, Calvo and Ayuso1993; Beltrán Reference Beltrán1993; Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924).

Honey-hunting scenes include a variety of climbing systems. They can be divided into two groups based on size, morphology and flexibility: rigid (self-supporting) ladders or masts, and flexible systems (including ropes and ladders with flexible stringer and rigid or flexible rugs). The difference could be indicative of the use of different raw materials.

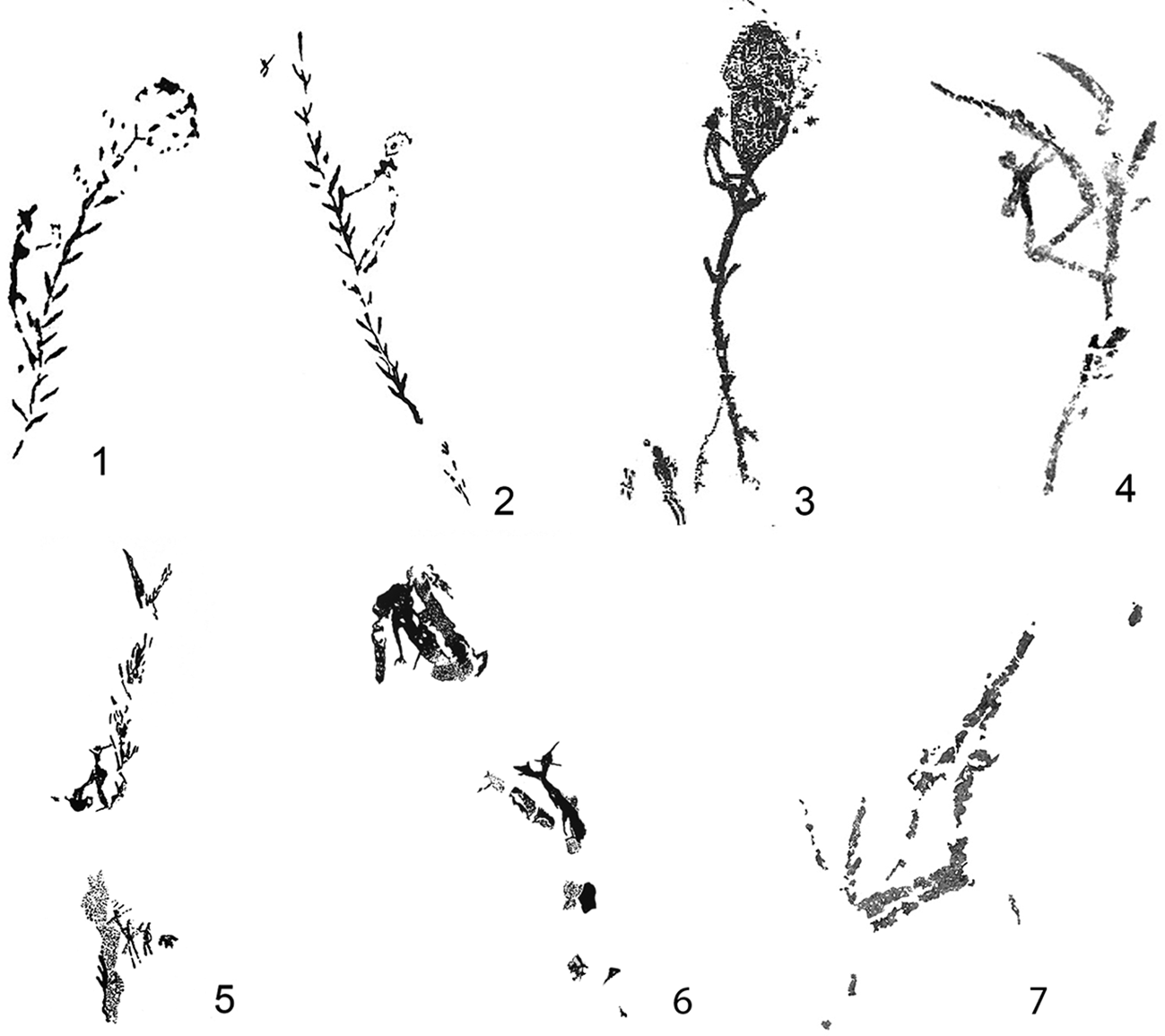

The first group includes branched linear strokes (spike-like shape) interpreted as tree trunks or masts (Fig. 3). They are much shorter and more rigid than other types and show a narrow distribution (river Martin basin). The best examples are in Covacho Ahumado, Los Trepadores, Los Recolectores, and La Higuera de Estercuel in Teruel and Mas d'en Josep and Remígia III in Castelló (Table 1). We rule out a potential tree surrounded by bees with a human figure standing next to it (maybe indicating that it is about to climb) described at La Vinya site (Castelló) (Martínez-Valle & Guillem Reference Martínez-Valle and Guillem2019) as the description published is unclear to us.

Figure 3. Rigid climbing systems (tree trunks, masts or branches). (1 & 2) Los Trepadores (after Beltrán Reference Beltrán2005); (3) La Higuera (after Baldellou Reference Baldellou2010); (4) Mas d'en Josep (after Domingo et al. 2003); (5) Covacho Ahumado (after Beltrán & Royo Reference Beltrán and Royo1997); (6) Los Recolectores (after Beltrán & Royo Reference Beltrán and Royo1997); (7) Remigia III (after LArcHer: A. Macarulla).

The second group, flexible climbing systems, includes a variety of examples (up to eight so far), most clearly pointing to the use of ropes and rope ladders. These flexible systems are depicted with thinner wavy lines, insinuating their plastic nature and adaptability to the shape of the landscape over which they climb. The depicted examples are much longer than previous types, some over 1 m long (which, given the scale of the drawings, could equal 25 m in real life). The use and installation of these flexible climbing systems is more complex and time-consuming, as they have to be installed, fixed and hung from the top, and then climbed up from the bottom (as deduced from the gear left at the bottom in several scenes).

Flexible ladders are more represented in LRA than rigid ones. They can be divided into different categories according to the degree of workmanship:

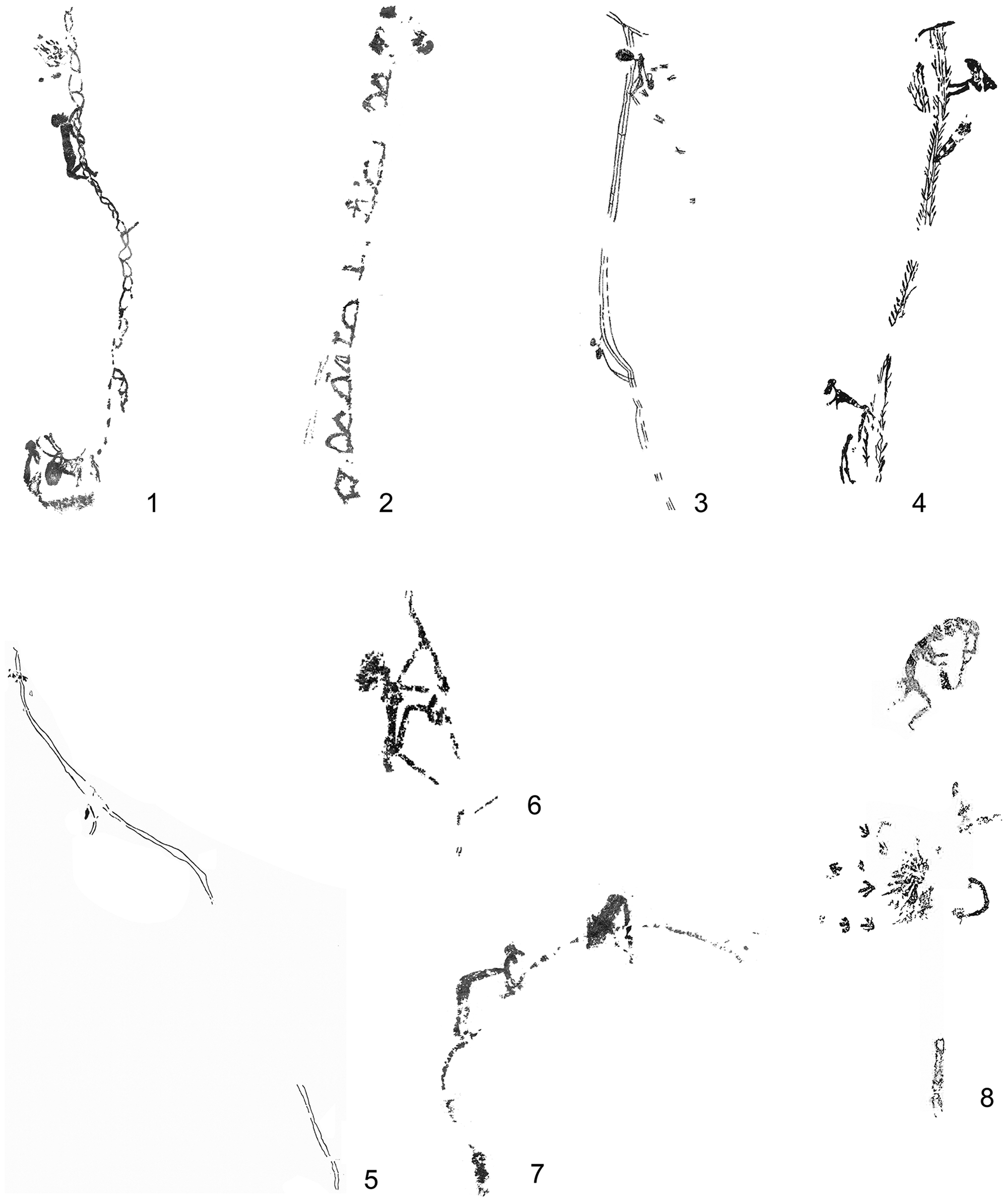

1. Ropes and long ropes. This is the simplest system, involving the use of one, two or even three long parallel ropes (Fig. 4). Some illustrate the use of a fixing element at the top (either as crossed branches or a linear stroke) from which the ropes were tied and hung (La Araña, Los Trepadores and maybe Abric de la Penya sites). At La Araña, three separate ropes are depicted, which were probably used to ascend with a special climbing technique. The real function of the top rung (probably made of wood) was to keep the ropes apart and prevent entanglement or constriction during ascent. Thus, it cannot be interpreted as a ladder. A similar solution was depicted at Los Trepadores site (Fig. 4.4). Here, three ropes hang from two crossed strokes (maybe trunks or branches). Short diagonal lines run along the ropes as handholds.

Figure 4. Flexible climbing systems. Stirrup ladders: (1) Barranco Gómez; (2) Cingle de l'Ermità (after LArchHer: I. Domingo). Ropes: (3) La Araña (Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924); (4) Los Trepadores (after Beltrán Reference Beltrán2005); (5) Abric V de la Penya (Ribera et al. 1995); (6) Cingle de la Mola Remígia (after Domingo Reference Domingo2005); (7) Cova Remígia V (after LArchHer: I. Domingo). Scales or ladders: (8) Arpán L (after Baldellou et al. 1993).

Other examples do not explicitly show where ropes hang from, such as Cingle de la Mola Remígia (Fig. 4.6), Mas d'en Salvador (one rope), Abric de la Penya (two ropes) (Fig. 4.5) or Remigia V (Fig. 4.7).

2. Rope ladder. These consist of two long parallel vertical ropes joined by short transverse rungs (made of rope or wood) knotted and placed every few centimetres. As such, they are complex systems, given the use of different elements that must be perfectly assembled.

There is only one rope ladder fairly well identified in Arpán shelter (Baldellou et al. Reference Baldellou, Painaud, Calvo and Ayuso1993) (Fig. 4.8).

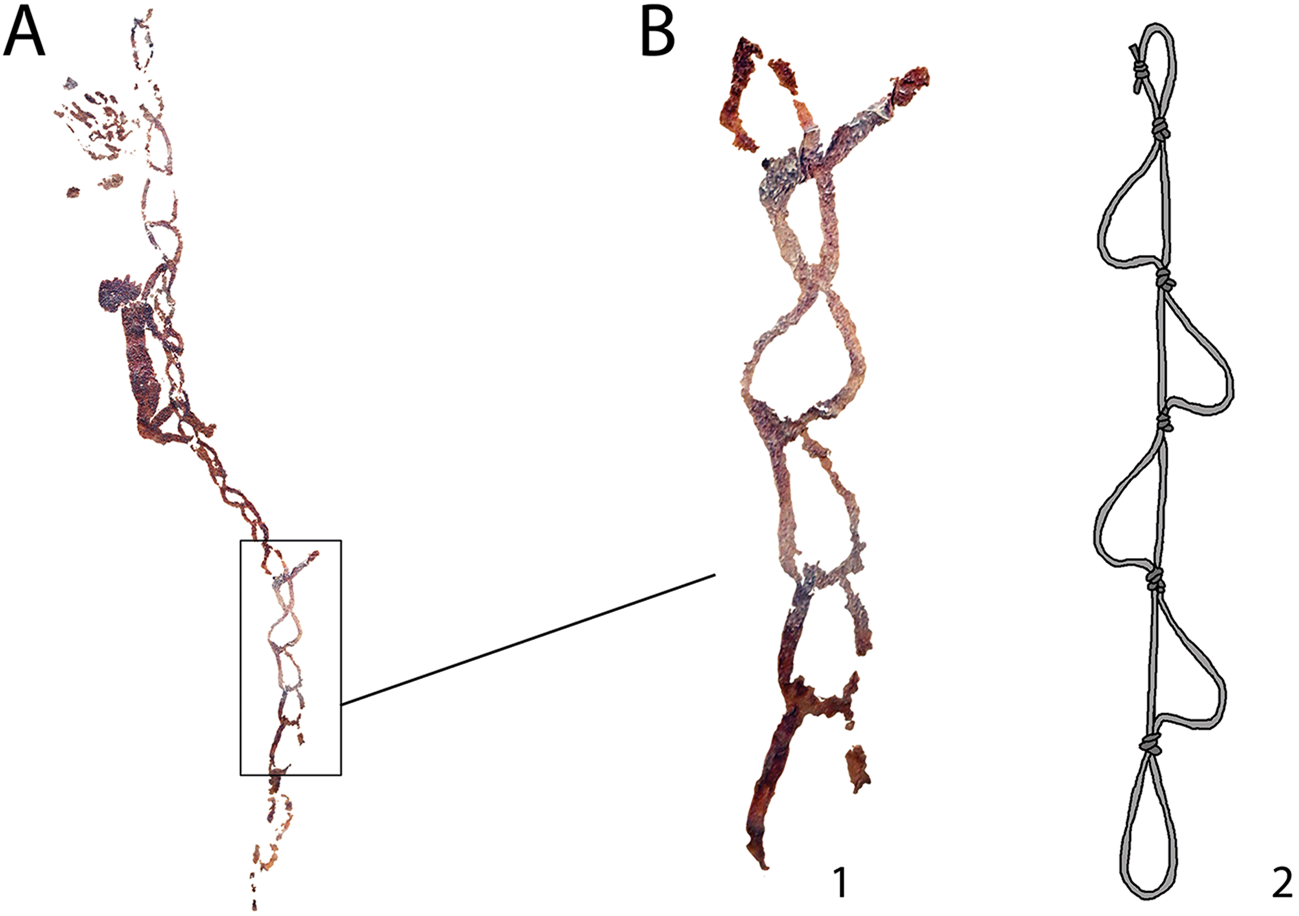

3. Stirrup ladder. It consists of a single rope, with stirrups or loops (in an ‘8’-like shape) tied into it every few centimetres. They are identical to those used today in alpine climbing (except for the materials). There are two main types of stirrup ladders, one with parallel sides between knots, so when the foot steps on the loop the rope becomes too tense and narrow and it is more difficult to set foot on the next loop. The second type is designed to facilitate insertion of the foot, using unequal lengths of the intermediate stirrup, so that the foot is not blocked by the tension. That is exactly what the Levantine artist of Barranco Gómez site depicted: a stirrup ladder with asymmetrical loops (Fig. 4.1 & Fig. 5). In this case, the length of the rope was extraordinary, based on the number of loops and the proportion of the motif depicted in relation to the climber.

Figure 5. (A) Digital tracing of part of the climbing scene at Barranco Gómez; (B) Comparison between the stirrup ladder depicted (1) and a sketch of a stirrup ladder used in current alpine climbing (2) (after original by Estado Mayor de la Defensa 1985). Note how the loops are smaller where the climber is, compared to the ends, probably because of the weight. A large dose of naturalism captured by the artist.

Another example can be found at Cingle de l'Ermità (Albocàsser, Castelló) (Viñas Reference Viñas1979–80), which Dams (Reference Dams1984, 106) has already interpreted as a ladder. Although the scene is not as well preserved as the previous one, we believe it is another example of a stirrup ladder with asymmetrical rungs, as several knots can be still recognized. In this case, one or maybe two linear humans climb up the ladder to reach three rounded shapes. Whether the artist intended to depict honeycombs or not is unclear, as there are no insects around. Two strokes hang down parallel to each other from the back of the lower human. As they are incomplete, we do not know whether they intended to depict safety equipment or, as seen in ethnographic contexts, they could be ropes employed to suspend containers used for collecting (Strickland Reference Strickland1982).

A similar motif has been recorded at Fuente de la Toba (Mateo & Carreño Reference Mateo and Carreño2010, 25), but this interpretation cannot be confirmed, given the absence of climbers.

Flexible ladders or climbing systems are easier to transport than rigid ones, but they are much more complex to use. Upon application of weight while climbing, the ladder bends and sways, complicating climbing for the inexperienced. The scene depicted in Barranco Gómez is a good example of this. Despite the restrictions imposed by the use of solid infill as one of the main Levantine painting techniques, through the use of different perspectives or points of view (Martínez-Bea Reference Martínez-Bea2006–08), the artist perfectly captured the right way of climbing these mobile ladders. Thus, the climber was depicted hanging from the back of the ladder with both hands, wrapping both hands and feet around it. A transverse stroke depicted in the central part of the ladder (possibly a stick) was probably used to secure it and prevent the ladder from swinging. Similar sticks are also observed at the scene from Cingle de l'Ermità. In this case, up to three sticks have been used to secure the ladder in three different sections. Even today, it is possible to find sticks nailed to the cliffs of these Mediterranean areas (Fig. 6). Where ethnographic information exists, they appear to be associated with the economic exploitation of wild honey (Domingo et al. Reference Domingo, Rives, Roman and Rubio2013; Salamero & Cuchí Reference Salamero and Cuchí2019; Viciano Reference Viciano1990Footnote 1).

Figure 6. Roca de las Estacas [Wooden Stakes Rock] in Mosqueruela (Teruel). (Photographs: courtesy of Sergi Monfort and Jesús Tena.)

The scene at Barranco Gómez is unique in LRA. It is so descriptive as to allow one to visualize the sequence of the action (as described by Villaverde Reference Villaverde and Martínez2005 or Domingo Reference Domingo, Davidson and Nowell2021, among others) and the temporal dimension involved in setting up the ladder for use and climbing. The first step was to install and fix the ladder, probably from the top, leaving it suspended. The climber then ascends the ladder from the ground after leaving a basket, a bow and a few arrows at the bottom.

The seasonal nature of honey harvesting also provides information on past temporality, but not necessarily on when these scenes were painted by Levantine artists. Ethnographic references from Spain indicate that honey from wild hives is collected at the end of September and October, after which bees begin eating it.

Raw materials and rope making

While the use of ropes is referred in the literature on LRA, not many authors reflect on aspects related to rope production. Only the materials used, such as esparto grass (Beltrán Reference Beltrán1982; Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1921; Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924; Jordá Reference Jordá1966, 51) or other natural fibres, such as fan palm (Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1921; Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924, 15) are referred to. Escoriza (Reference Escoriza2002, 77) describes some basketry or rope-making scenes in which she sees probable branch or reed manipulation (e.g. Los Trepadores or Barranc de la Famorca VI sites). Jordà (Reference Jordán and Viñas1974, 219) suggest twisted fibres may have been used to produce some objects depicted in LRA. Based on this idea, and looking for parallels in the archaeological record (fibres preserved at Cueva de los Murciélagos of Albuñol, Cabezo Redondo, El Argar sites, etc.) or indirect evidence (such as the Bell Beaker Culture with corded pottery of Vila Filomena), he refers to these LRA objects to suggest an Eneolithic or even a Bronze Age affiliation for these paintings (Jordá Reference Jordá1974, 81), stressing that the development of textiles should be related to advanced agricultural cultures (Almagro Reference Almagro1951, 75). On the contrary, Hernández-Pacheco (Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924, 15) stated that the origins of textile production date back to pre-Neolithic times, as indirectly demonstrated by the invention of the basal drilled needles in the late Solutrean. Today, the earliest direct evidence in the Mediterranean Iberian are some rope fragments made with esparto grass and recovered at the Epipaleolithic levels of Coves de Santa Maira (Aura et al. Reference Aura, Pérez, Carrión, Seguí, Jordá, Miret and Verdasco2020, 585), but other more recent examples, in addition to those named above, include those at Cova de les Cendres (Carrión Reference Carrión2005) dating to Neolithic times, or Cabezo Redondo (Hernández et al. Reference Hernández, García, Collado and Nash2012; Soler Reference Soler1987), Terlinques or Lloma de Betxí dating to the Bronze Age (Fernández et al. Reference Fernández2010; Jover et al. Reference Jover, López, Machado, Herráez, Rivera and Precioso2001; Pedro de Reference Pedro de and Soler2006).

Esparto grass (Stipa tenacissima) is considered the best fibre for rope making (Alfaro Reference Alfaro1984, 185), even though other fibres have served similar purposes since ancient times: flax (Linum usitatissimum), reed (Phragmites sp.), hemp (Cannabis sativa), small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata), common reed grass (Ampelodesma mauritanica), papyrus (Cyperus sp.), dwarf palm (Chamaerops humilis) or nettle (Urtica vagans) (Alfaro Reference Alfaro1984; Romero-Burgués et al. Reference Romero-Burgués, Piqué, Picornell, Calvo and Fullola2021; Ruiz Reference Ruiz2012). The use of any fibre could be constrained by environmental and weather conditions, as certain species require special conditions to grow. Such is the case of esparto grass, requiring steppe territories, with cold winters, very hot summers and low rainfall. Nowadays, these soil and climate conditions can be found in the arid area of the Spanish Mediterranean region, from Malaga to Castelló, and some other inland areas (Castilla La-Mancha, Aragón). This is a surprisingly similar distribution to that of LRA.

Ethnographic information collected in the Iberian peninsula describes traditional processing of esparto grass as divided into four phases (Beltrán Reference Beltrán2005): harvesting, fermentation, drying and crushing. It is a complex process requiring a high level of pre-planning, as well as elaboration.

Alfaro (Reference Alfaro1984, 186) describes two different techniques for rope making: twisting ropes and plaiting ropes made by previously non-twisted elements. Depending on the number of simple elements, the thickness of the final product would vary. Using these techniques, ropes of enough thickness and strength (with diameters of 2 cm) (Alfaro Reference Alfaro1984, 193) to hold a person can be produced.

Discussion

Hanging for what? Ropes and associated activities

Previous scholars have suggested a direct relationship between rope climbing systems and honey hunting in LRA (Bellés Reference Bellés1997; Beltrán Reference Beltrán1961–62; Beltrán & Royo Reference Beltrán and Royo1994; Beltrán & Vallespí Reference Beltrán and Vallespí1960; Blasco Reference Blasco1975; Reference Blasco2005; Breuil Reference Breuil1912; Reference Breuil1920; Codina Reference Codina1949; Crane Reference Crane2005; Crane & Graham Reference Crane and Graham1985; Dams Reference Dams1978; Reference Dams1984; Dams & Dams Reference Dams and Dams1977; Escoriza Reference Escoriza2002; Galiana Reference Galiana1985; Hernández-Pacheco Reference Hernández-Pacheco1921; Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924; Jordá & Alcácer Reference Jordá and Alcácer1951; Jordán Reference Jordán and Viñas2019; Lillo Reference Lillo2014; Martínez-Rubio Reference Martínez-Rubio, López, Martínez-Valle and Matamoros2009; Olària Reference Olària2011; Porcar Reference Porcar1949; Porcar et al. Reference Porcar, Obermaier and Breuil1935; Ribera et al. Reference Ribera, Galiana, Torregrosa and Llin1995; Ripoll Reference Ripoll1963). However, there is no direct correlation between climbing and honey hunting. Some climbers seem isolated, with no link with any particular activity. But a number of them are depicted in honey-hunting scenes, but … why honey?

Bee products were important in prehistory for a variety of economic, technological and cultural functions (Roffet-Salque et al. Reference Roffet-Salque, Regert and Evershed2015). As food, it is rich in calories (Crittenden Reference Crittenden2011; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Schoeninger, Bunn, Pickering and Marlett2001), with 80–95 per cent sugar. Some researchers suggest that it could replace or reduce meat consumption as a primary element of the diet (Blasco Reference Blasco1975, 53), reducing dependency on hunting or, at least, replacing it in some circumstances. Honey is one of the few sweet foods available in nature and it has good properties as an important ingredient in spirits. In addition, beeswax is a good insulating material for containers and a natural fixative useful for mastics (e.g. to haft lithic tools, in bow making, etc.) (Baales et al. Reference Baales, Birker and Mucha2017), as well as used as medicine (as part of ointments for healing, dental treatment, etc.: Oxilia et al. Reference Oxilia, Peresani and Romandini2015) or cosmetics (preventing cracked skin).

Whether the representation of wild beehives and honey-hunting scenes, or even the honey-harvesting activity itself, had both socio-economic and symbolic values simultaneously for Levantine societies, as observed in other current populations through ethnology, is difficult to prove, as different societies have different practices and beliefs. Similarly, whether it was restricted to particular social groups is also challenging to assess, as the sex or age of the climbers is ambiguous in LRA. What the scenes do tell us is that the use of beeswax products is not a recent phenomenon.

Ethnographic accounts, though distant in time and space from LRA and artists, are of interest to illustrate human behaviour and practices related to this activity in various parts of the world. For example, Godelier (Reference Godelier1989, 57) described how honey hunting was restricted to men among Mbuti people (Indigenous pygmy groups from Congo). Gimbutas (Reference Gimbutas1996) refers to the symbolic dimension of ‘bees’ in the Mediterranean sphere, where they are considered as a vital generating force, while Lewis-Williams (Reference Lewis-Williams1982, 437) reports the symbolic value among Southern San people and from modern !Kung as a symbol of potency (Pager Reference Pager1973; Reference Pager1976). In northern Australia and the Kimberley, honey and wax produced by native stingless bees are well-priced and even traded resources by Aboriginal people. As described by Brady et al. (Reference Brady, Bradley and Wesley2019 127), beeswax ‘features heavily in social, economic and ceremonial aspects of Aboriginal life’. In fact, it has been even used, for at least the last 4000 years, to produce a unique Australian type of rock art known as beeswax rock art (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Wesley2019; Brandl Reference Brandl1968; May et al. Reference May, Shine, Wright, David, Taçon, Delannoy and Geneste2017; Nelson Reference Nelson2000; Welch Reference Welch1995).

Honey-hunting scenes are not exclusive to LRA, since similar scenes have also been recorded in other parts of the world, including uKhahlamba-Drakensberg, in which humans use ladders or other climbing systems, to reach the honeycombs (Guy Reference Guy1972, 161–2; Hollmann Reference Hollmann2015, 13; Mazel Reference Mazel1982, 68); or central India, with depictions of people (both men and women) sitting in trees, smoking hives and climbing ladders to access honeycombs (Mathpal Reference Mathpal1984). Honeycombs and Dreaming (mythological) stories and characters related to native bees are also represented in northern Australian rock art (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Wesley2019; Brandl Reference Brandl1968; May et al. Reference May, Shine, Wright, David, Taçon, Delannoy and Geneste2017; Nelson Reference Nelson2000; Welch Reference Welch1995).

The use of ropes and ladders for honey hunting is well documented in the ethnographic record in different parts of the world. And many of these examples have been recurrently referenced in publications on LRA since early dates. Breuil, when referring to the iconic hunting scene from La Araña site, explains that the scene reminds him of ‘un montant à une corde (?) ou à un mât (?) dans l'attitude des Australiens qui gripent avec les mains et les pieds sans s'aider des genoux’ (Breuil Reference Breuil1912, 551). Obermaier and Wernert (Reference Obermaier and Wernert1919) referred also to ethnographic parallels with Bushman and Pigmy people from Africa and Irula people from India, describing the use of ropes in honey hunting. Dams referred to honey gatherers from Drakensberg (Natal) (Dams Reference Dams1984, 231) and Beltrán mentioned some groups from Nepal (Beltrán & Royo Reference Beltrán and Royo1997). More interestingly, due to geographical proximity, Hernández-Pacheco (Reference Hernández-Pacheco1924, 14) collected local ethnographic information describing how honey was still gathered in the study area using ropes and ladders in winter (when bees were sleeping).

In fact, honey-gathering has been an economic complement until today in many areas of Mediterranean Iberia. This activity involves both the collection of honey from artificial hives (many of them placed in shelters which sometimes include rock art) and from natural hives located within holes, cracks and crevices in the upper part of cliffs. Today it is still possible to see wooden sticks attached to the vertical walls of some ravines that were once used for this purpose. And we can still collect oral traditions and ethnological records attesting to this activity (Domingo et al. Reference Domingo, Rives, Roman and Rubio2013; Fédensieu et al. Reference Fédensieu, Moulin and Domenge2002; López Reference López1994, 37; Salamero & Cuchí Reference Salamero and Cuchí2019).

Conclusions

Although the use of fibres to craft objects and ropes is well attested in the prehistoric record from early dates, their use in certain practices, such as climbing, is difficult to demonstrate from the archaeological record. On the contrary, as discussed in this paper, some rock-art traditions (and in particular LRA) offer unique graphic testimonies to conclude that climbing and the use of climbing gear to minimize risks was already mastered by Levantine societies. This activity is linked to various practices, such as boar hunting and honey hunting. In the wild boar hunting scenes, climbing seems to involve mostly getting into a tree (as in Mas d'En Josep or Cova Remígia III), while in honey-hunting scenes climbers use either vegetal elements or various types of ropes and rope ladders to reach their targets.

The unique honey-hunting scene from Barranco Gómez site illustrates the use of a truly complex rope-making technology. Close observation of this depiction does not assist in identification of the rope-making techniques (whether twisted or plaited fibres), but the use in climbing and the length show that Levantine societies were technologically advanced in the production of quality ropes. We estimate that each loop of the ladder (considering a minimum of 25 cm high and 20 cm wide) requires up to 80–85 cm of rope (including the necessary knots), so the rope length was possibly 25 m after the 29 stirrups depicted in the scene. Given that, the ladder itself could have been up to 7.5 m in length. The proportions of the length of the ladder and the height of the climber (assuming a height of 1.7 m) would fit perfectly.

The production of a 25 m long rope to make the ladder most likely involved substantial time and effort, both to collect the raw materials and to manufacture the rope. Furthermore, the risk inherent in climbing such a height using simple rope ladders shows the importance of honey hunting for these human groups.

Interestingly, honey-hunting scenes are only represented in the most recent phases of the Levantine sequence and their distribution seems to be restricted to Macizo del Caroig and Maestrazgo territories. The use of ropes for climbing is only documented for the so-called ‘Lineal’ (Martínez-Bea Reference Martínez-Bea2005; Utrilla & Martínez-Bea Reference Utrilla and Martínez-Bea2007) or Cingle type (Domingo Reference Domingo2005; Reference Domingo2006), one of the most recent styles. The best and more elaborate examples belong to this phase, even though a few other examples have been recorded in the most recent phase of this artistic cycle, named ‘filiform’ or ‘lineal’ according to Domingo's classification.

As noted above, despite the small number of climbers documented in LRA, the diversity of climbing systems represented is considerable. The most sophisticated examples are in the northern sites (Barranco Gómez, Los Trepadores, Los Recolectores, Cingle de l'Ermità, Arpán) while the simplest (only long ropes or groups of parallel ropes) have a wider geographical distribution, with the longer ropes located further south (La Araña, Abric de la Penya).

What is important is that Levantine groups had a refined technique for rope making, which was adapted to produce long ropes for climbing activities. When the action represented in the scenes displaying rope equipment can be deduced, honey hunting is the only well-defined activity. While this activity was depicted in different parts of the Levantine territory in the final stages of the sequence, it is completely absent in the initial stages, marking a significant change in the cultural treatment this activity had over time.

As deduced from the analysis of the Levantine scenes, the exploitation patterns of bee products involved several phases: 1. spot selection (as determined by the location of the wild beehives); 2. anchoring the ladder or ropes in a place above the hive, and dropping them down; 3. once the climbing system is secured, in some cases (as in Barranco Gómez and Cingle de l'Ermità) with intermediate safety locking branches or wooden sticks, it is ready to be used as required. From analysis of the scenes, we deduce climbers accessed from below, more than descending, as the objects (bow, arrows, bag …) and climber's companions are found there.

A further aspect of interest related to the societies producing these scenes is the seasonality of this particular practice. Wild honey is collected between September and October, just before bees begin to feed on the honey, so it is better for the collectors to act before the bees. This does not necessarily imply that the scene was also depicted at this time of the year.

Honey and beeswax must have had a variety of uses for Levantine societies, becoming so valuable as to invest a good deal of time and effort in making such large ropes, and in depicting this type of scene. They also devised and improved climbing systems enabling them to literally hang over the void.

Acknowledgements

Research in this paper has received financial support from different sources: ERC– Consolidator Grant LArcHer project, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 819404) and HAR2016-80693-P, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and Generalitat Valenciana (CIDEGENT/2018/43). M.B. was postdoctoral senior researcher at UJI funded by the ERC-CoG LArcHer project when a significant part of this research was conducted. He is member of the Project HAR2017-85023-P (funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness), Research Group Primeros Pobladores y Patrimonio Arqueológico del Valle del Ebro (‘P3A’) (H-07) (funded by Government of Aragon and European Social Fund) and Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Patrimonio y Humanidades (IPH), University of Zaragoza (Spain). Tracing of a climber from Remígia III was done by A. Macarulla (Predoctoral Researcher from LArcHer ERC-CoG project).