No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

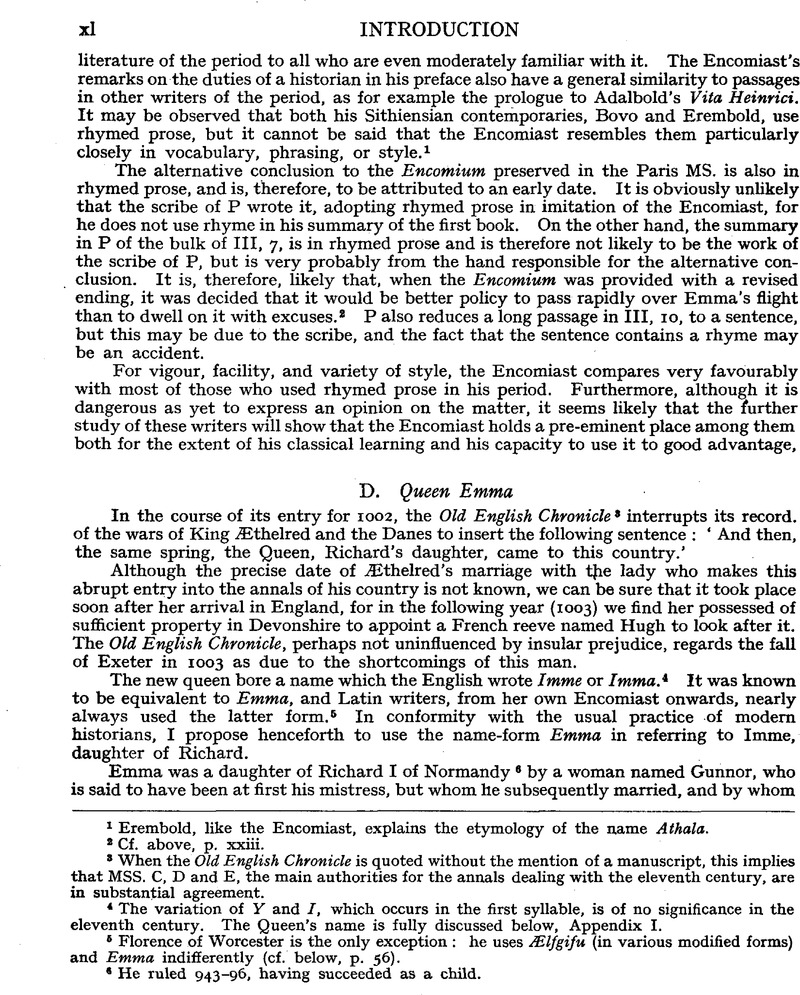

page xl note 1 Erembold, like the Encomiast, explains the etymology of the name Athala.

page xl note 2 Cf. above, p. xxiii.

page xl note 3 When the Old English Chronicle is quoted without the mention of a manuscript, this implies that MSS. C, D and E, the main authorities for the annals dealing with the eleventh century, are in substantial agreement.

page xl note 4 The variation of Y and I, which occurs in the first syllable, is of no significance in the eleventh century. The Queen's name is fully discussed below, Appendix I.

page xl note 5 Florence of Worcester is the only exception: he uses Ælfgifu (in various modified forms) and Emma indifferently (cf. below, p. 56).

page xl note 6 He ruled 943–96, having succeeded as a child.

page Xli note 1 See Dudo (ed. Duchesne, pp. 152–3).

page xli note 2 iv. 18. By a curious oversight, J.-M. Toll, Englands Beziehungen zu den Niederlanden bis 1154 (Historische Studien, 145), p. 41, makes Emma a child of her father's first wife, Emma, daughter of Hugh of Paris.

page xli note 3 To whom Dudo, loc. cit., alludes, saying that Richard genuit duos filios, totidem et filias, ex concubinis.

page xli note 4 See further on Emma's names, Appendix I.

page xli note 5 See Appendix II.

page xli note 6 Freeman (N.C., I, chap. 4) and Green (Conquest of England, chaps. 5 and 6) are the chief offenders. The evidence which they advance for the assumption, that England and Normandy were antagonistic in the tenth century, is mainly the cordial attitude of England towards the Bretons, but it is now generally recognised that the Normans against whom the Bretons were then struggling were those of the Loire, not those of the Seine (see Stenton, p. 344, and detailed discussion by De la Borderie, referred to above, p. xxii, n. 10). Green also attempts in a most hazardous manner to see an anti-Norman policy in some of the English royal marriages of the tenth century. It is also unwise to regard the English support of Louis d'Outremer as inspired by an anti-Norman tendency in English policy, or to place undue weight on the fact that, when in 938 Arnulf of Flanders captured the wife and children of Herlwin of Montreuil, who appears to have been at the time in the same group as the Normans among the ever-changing French political combinations, they were sent to England for custody. The only recorded instance of direct contact between England and Normandy before Æthelred's reign is a letter written by an abbot of St. Ouen's and addressed apparently to King Eadgar : it is a request for help with restorations (Memorials of St. Dunstan, Rolls Series, pp. 363–4). In Æthelred's time, commerce between London and Normandy was apparently regular, for the dues to be paid by Norman merchants at London are mentioned in a legal code, which also shows that merchants from Rouen were especially privileged (Liebermann, Gesetze, i. 232).

page xlii note 1 See Stenton, pp. 370–1. It is, however, only a theory, though a reasonable one, that the cause of the friction was that the Normans allowed the Scandinavian invaders of England to use their ports.

page xlii note 2 v. 4.

page xlii note 3 So, in essentials, N.C., i. 302–3, and Steenstrup, Normandiets Historie, p. 162.

page xlii note 4 See N.C., i. 304 and note, on Gaimar's story that Æthelred crossed to Normandy in person to fetch his bride. Henry of Huntingdon (Rolls Series, p. 174) and Æthelred of Rievaulx (Patrologia, cxcv. 730) say that messengers were sent to Normandy. Æthelred's brother-in-law did not hesitate to conclude a treaty with Sveinn, permitting him to sell in Normandy the plunder won in one of his invasions of England (N.C., i. 342), but this was at least not an act of open hostility. Henry of Huntingdon (Rolls Series, p. 176) says that Æthelred asked Richard for help and advice in 1009, when an attempt to improve the English resistance to the Danes was being made.

page xlii note 6 See below, p. lxiv, n. 3.

page xlii note 7 See Old English Chronicle.

page Xliii note 1 Ed. Duchesne, p. 655.

page xliii note 2 See below, pp. xliv–v.

page xliii note 3 Examples are numerous : e.g., N.C., i. 736; Oman, England before the Norman Conquest, p. 613; Bugge, , Smaa bidrag til Norges historie paa 1000-tallet (Christiania, 1914), p. 10Google Scholar.

page xliii note 4 Gesta Regum, ii. 196.

page xliii note 5 Entry for 1043, C and D, mis-dated 1042, E.

page xliii note 6 See below, p. lxvii.

page xliii note 7 See below, p. xlv.

page xliii note 8 William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, ii. 165, has an unsupported theory that Æthelred alienated the affections of Emma by his infidelity. There is no need to be surprised that William, who tells so many stories of the moral imperfections of the kings of the West-Saxon house, desires to put Æthelred on a level with the rest, but it is noteworthy that he has no anecdotes of his usual kind to support his view. Palgrave (Normandy and England, iii. iii) seems to derive from a confused memory of William's words a belief that Emma fled back to Normandy soon after her marriage. Roger of Wendover (ed. Coxe, i. 427) misunderstands William so far as to explain Æthelred's quarrel with Richard I, who was six years dead when Emma came to England, as due to the Duke's disgust at the treatment meted out to his daughter.

page xliv note 1 Lestorie des Engles, 4138 ff.

page xliv note 2 See above, p. xl.

page xliv note 3 Gaimar says that Ælfthryth had held the same property previously.

page xliv note 4 MS. E of the Chronicle adds to the annal for 1013 that, while abroad, Ælfsige visited Bonneval, where he purchased the body of St. Florentine, which he afterwards brought back to England. Roger of Wendover (ed. Coxe, i. 448) has an unsupported story that Eadric Streona went abroad with Emma, and remained with her two years.

page xliv note 5 See below, p. xlv, n. 3.

page xliv note 6 M.G.H.S., iii. 849. The details of Thietmar's account are very discreditable to Emma, for the Danish terms, to which she is said to have agreed, include the delivery of her stepsons Eadmund and Æthelstan for execution; they need not, however, be taken seriously.

page xliv note 7 William of Jumièges, v. 9, believed, like Thietmar's informant, that Emma was in London during Knútr's siege of the city; he assumes, however, that Kniitr in some way got her out of the city and married her as soon as Æthelred died. Gaimar, Lestorie des Engles, 4207, says that Emma was at Winchester when Æthelred died, but he does not make it clear what he thought her subsequent movements were. William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, ii. 180, says that Richard of Normandy gave his sister in marriage to Knútr, thus showing that he believed Emma was in Normandy when the marriage was arranged.

page xlv note 1 P. xxi.

page xlv note 2 Gesta Regum, ii. 181. Raoul Glaber, ii. 2, also suggests that Knútr's object was to improve relationships with Normandy.

page xlv note 3 The Encomiast (ii. 18) says that the young princes were sent to Normandy after Hörthaknútr's birth. It is possible, therefore, that Ælfred returned, like Eadweard, in 1014, and that they both remained in England till after their mother married Knútr. Ordericus Vitalis (ed. Duchesne, p. 655) says, however, that they fled when Knútr invaded England, so perhaps they escaped in 1015 or 1016, returned with their mother in 1017, and were sent back later. (On a deed supposed to be enacted by Eadweard in Flanders in 1016, see below, p. lxiv.) Ordericus (loc. cit.) adds that Godgifu was in Neustria with her brother (he fails to indicate which) during Knútr's invasion of England. It is fairly certain that she would withdraw in 1013 (cf. above, p. xliv), and the words of Ordericus imply that, if she returned in 1014, she was able to escape in 1015 or 1016. It would be possible to take the word filios in Enc. II, 18, to mean ' children ', and assume that Godgifu again returned to England with her mother in 1017, and was later sent away with her brothers. William of Jumièges (vi. 10) obviously much over-simplifies the movements of Ælfred and Eadweard, when he says that they left England with their father during Sveinn's invasion, and were left behind by him on his return. At least in the case of Eadweard, we know that this is untrue.

page xlv note 4 Emma has been much blamed for her treatment of her older children by modern historians : examples occur in most treatments of the history of the period, so I do not give references.

page xlv note 5 See below, p. xlviii.

page xlv note 6 N.C., i. 410

page xlvi note 1 It is very noticeable that the Encomiast, in his account of the wooing of Emma, has no word about her relatives; the lady herself is approached directly and exclusively.

page xlvi note 2 This is the aspect of the marriage which disgusts William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, ii. 180, who does not know whether the match was more disgraceful to Richard of Normandy, or to a woman ‘ quae consenserit ut thalamo illius caleret qui uirum infestauerit, filios effugauerit’

page xlvi note 3 Excellent examples of this sense will be found in Lewis and Short, s.v. ‘ virgo ’, IIa.

page xlvi note 4 Steenstrup (reference above, p. xix) sees that the Encomiast's words are perfectly defensible, but fails to recognise his obvious intention to deceive. Similarly Langebek, in his note on the passage, suggests that Emma is called virgo in view of her chastity. Most historians have, however, emphasised the mendacity of the Encomiast, but have not noticed the skill with which he has refrained from verbal untruth.

page xlvi note 5 See Appendix II.

page xlvii note 1 Raoul Glaber, ii. 2, states that Richard of Normandy and Emma persuaded Knútr to make peace with the king of Scots. It is impossible to say if a memory of some actual part played by Emma in Scottish affairs underlies this. Roger of Wendover (ed. Coxe, i. 463) curiously connects Knútr's marriage with his dismissal of his Danish fleet the next year, and attributes the latter action to Emma's persuasion. This can hardly have any foundation : such false inferences are frequent in second-hand chronicles.

page xlvii note 2 See below, p. 75.

page xlvii note 3 Prior Godfrey of Winchester dwells on Emma's generosity to the church and the poor in his epigram on her (Wright's Satirical Poets, Rolls Series, ii. 148). Godfrey's first line, Splendidior gemma meriti splendoribus Emma, may echo some popular verse known to Henry of Huntingdon, who calls the Queen Emma, Normannorum gemma (Rolls Series, p. 174).

page xlvii note 4 Gesta Regum, ii. 181 and 196.

page xlviii note 1 See the Viking Society's Saga-Book, xii. 131; and Birch's ed. of Hyde Liber Vitae, frontispiece and p. 57.

page xlviii note 2 Memorials of St. Edmund's Abbey (Rolls Series, i. 341).

page xlviii note 3 Historia Novorum (Rolls Series, pp. 107 ff.).

page xlviii note 4 F's Latin version (contradicting the English) says the Old Minster, but the sacred object seems to have been preserved at the New Minster (see Plummer, , Two of the Saxon Chronicles, ii. 222Google Scholar).

page xlviii note 5 William of Malmesbury, Gesta Pontificum (Rolls Series, pp. 419–20).

page xlviii note 6 See N.C., i. 473 ff.

page xlviii note 7 William of Jumièges, vi. 6. Toll, Englands Beziehungen zu den Niederlanden, p. 29, regards Baldwin V's mother as a sister of Emma: this is a double error. Baldwin IV's second wife was a niece of Emma (William of Jumièges, v. 13), but she was not the mother of Baldwin V, who was a son of his father's first wife, Otgiva of Luxemburg.

page xlviii note 8 This writ is addressed to Earl Ælfgar : since he was not an earl before the exile of Godwine in 1051, the document must belong to the last year of Emma's life.

page xlviii note 9 See Miss Robertson's notes on the documents.

page xlix note 1 Her residence at Winchester was still known as domus Emmae reginae in William I's reign; see N.C., iv. 59, n. 2.

page xlix note 2 Old English Chronicle; MS. C and E describe the incident in identical words, but D has another version, the only one which mentions the part played by the great earls. C adds a notice of Stigand's deposition and its cause.

page xlix note 3 N.C., ii. 60 ff.

page xlix note 4 A. Bugge, reference as above, p. xliii, n. 3, attempts to defend as serious history the story of the Translatio S. Mildrethae, that Emma's fall was due to her having urged Magnús of Norway to invade England, offering him her hand and wealth. It is not impossible that Emma dreamed in her dotage of repeating her recovery of her position in 1017 by similar means. I think it very unlikely that she had any strong preference for one dynasty as such against another, though this view is advanced, Stenton, pp. 420–1: cf. above, p. xxii.

page xlix note 5 She signs K. 788, which is dated 1049 by a late endorsement, but the signatures show that it belongs to an earlier period : Ælweard signs as bishop of London, and he died in 1044, and, as Stigand signs as a priest, the document presumably belongs to 1043–4, during the period of his deposition from the bishopric of Elmham.

page xlix note 6 Dated 1051 by MS. C. of the Chronicle, which starts the year at Easter or at the Annunciation in some annals in this period (see E.H.R., xvi. 719–21); cf. MSS. D and E. C is the only manuscript to mention the Queen's place of burial.

page xlix note 7 See Victoria History of Hampshire, v. 56.

page xlix note 8 See F. Lot, L'élément historique de Garin le Lorrain, in Études ‥‥ dédiées a Ga briel Monod (Paris, 1896), p. 205.

page 1 note 1 Rolls Series, p. 171.

page 1 note 2 Ord. Vit., ed. Duchesne, p. 487.

page 1 note 3 Ed. Thorpe, i. 204–5.

page 1 note 4 Gesta Regum, ii. 199.

page 1 note 5 M.G.H.S., ix. 301.

page 1 note 6 ii. 762.

page 1 note 7 Ibid.

page 1 note 8 N.C., iv. 743.

page 1 note 9 Ed. Guérard, i. (Paris, 1840), 173.

page 1 note 10 Amiens, 1840, p. 160.