Introduction

Across the democratic world, the forces of backlash, illiberalism and exclusion are transforming the political landscape. Immigrants are being attacked politically and sometimes assaulted physically, and other minorities are often pilloried and marginalized in political life. Some commentators argue that this sort of exclusion is the inevitable result of the way that modern states are built around ideologies of nationalism. On this view, the inclusion of minorities will only be possible if and when we shift to a postnational world order.

Others argue, however, that an inclusive nationalism is possible, under two conditions. The first condition is that majorities adopt a conception of the nation that allows immigrants and other types of minorities an accessible path to full membership. The second condition is that immigrants and minorities are seen as embracing that path and thereby showing their commitment to joining the nation as an “ethical community.”Footnote 1 Much has been written on the first condition, including detailed studies of the (gradual, uneven, fragile) liberalization of naturalization and enfranchisement policies over time to remove racial, religious and other ascriptive barriers to full citizenship,Footnote 2 as well as efforts to conceive of multicultural democracy and forms of political community that have space in them for the recognition and inclusion of national minorities (see, for example, Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka1995; Ivison, Reference Ivison2002; Gagnon and Tully, Reference Gagnon and Tully2001). However, much less has been written about the second condition. Are newcomers and national minorities seen by the majority as committed to a larger “we”? Are they seen as embracing and upholding the “ethic of membership” that makes the nation an ethical community,Footnote 3 including the commitments of loyalty and solidarity that are often said to be constitutive of nationhood?Footnote 4

If this second condition is not met—if immigrants and other minorities are perceived by the majority as less committed to the national “we”—they are likely to suffer what we will call “membership penalties” (Banting et al., Reference Banting, Kymlicka, Harell, Wallace, Gustavsson and Miller.2020; Harell et al., Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021, Reference Harell, Kymlicka, Banting and Crepaz2022). They may be formally admitted into the nation but continue to be seen as less deserving and their claims-making seen as less legitimate. They would not be excluded from the nation but rather subject to a “form of differentiated and hierarchized inclusion” within the nation, creating a hierarchy between a privileged ethnonational core and penalized minorities (Antonsich and Petrillo, Reference Antonsich and Petrillo2019: 719). These membership penalties are not precluded by citizenship; members of minorities who are citizens can still suffer such penalties.

Our aim in this article is to test whether we can identify such membership penalties rooted in perceptions of the (lack of) moral commitment to the nation and their consequences for political inclusion. In principle, such membership penalties could show up in a variety of policy domains. For example, perceptions of minorities’ lack of commitment could affect whether minorities are seen as deserving of welfare state benefits (see, for example, Harell et al., Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021). There is indeed a growing literature on perceptions of the deservingness of minorities in relation to the welfare state and how perceptions of their “we”-ness affects these deservingness judgments.Footnote 5

However, our focus in this article is on a more specifically political issue: namely support for claims-making by minorities in the political process. We are interested in political or democratic solidarity, as distinct from the social solidarity implicit in the welfare state.Footnote 6 In our view, this is a particularly important domain for exploring membership penalties. It is one thing to extend social protection to immigrants and minorities but quite another to accept that these groups have the right to (co)determine the future of the country. In colloquial terms, the test of whether someone belongs (to a family or to a nation) is not whether they are welcome in one's home but whether they have the right to move around the furniture. And it is possible that majorities only extend the right to move around the furniture to those minorities whom they see as morally committed to the national “we.” Insofar as the majority has doubts about whether minorities are willing and loyal members, the majority may give less weight to the voices and interests of these groups and give them less of a role in determining the nation's future.Footnote 7

We believe that this is a central issue for the future of multicultural democracies. Claims-making is an essential part of democratic politics, and so whether immigrants and national minorities enter the political process on equal terms is a crucial test of any truly progressive conception of inclusive nationalism. A nationalism that enabled newcomers to become citizens but left them stigmatized and suspect as democratic actors would hardly serve as an effective counter to the illiberal and undemocratic forces we see today. Similarly, a nationalism that sees demands from internal minorities for recognition and accommodation as suspect or hostile to a national “we” is equally problematic.

Our aim, therefore, is to better understand attitudes toward minority claims-making. To do so, we draw on a unique survey experiment collected among a sample of 2,100 Canadians designed to explore how citizens react to a series of questions regarding minority claims-making, and we vary the group making the claim, the types of claims made and the means of making the claim. As we will see, the evidence suggests that immigrants and national minorities in Canada do indeed face a “membership penalty” in terms of the perceived legitimacy of their claims-making. Their right to engage in claims-making is consistently seen as lower than that of the majority, and part of the explanation for this is majority perceptions of the minority's lack of commitment to the larger society (what we will call “membership perceptions”). To be sure, other factors are also at work, including old-fashioned out-group animosity as well as perceptions of need. But our evidence suggests that even when controlling for other factors that affect deservingness judgments, membership perceptions matter. Moreover, this is true not just for immigrant newcomers but also for French-speaking Quebeckers and Indigenous peoples. All three groups are penalized for their perceived lack of moral commitment to the larger society.

These findings raise a number of complicated issues, both empirically and normatively. Normatively, we might think that it is inappropriate to expect minorities to prove their loyalty to the larger society in order to be seen as equal democratic agents. This is particularly true in relation to colonized Indigenous peoples or to historic substate nations who have their own national projects and who have been the victims of the state's nation-building policies. Why should they feel loyalty to a larger society that has colonized or conquered them? And even in relation to immigrants, we might worry that the majority's perceptions of moral commitment are deeply skewed and that immigrants are being subjected to unreasonable tests of commitment that inevitably produce membership penalties. If the prospects for inclusive nationalism go through majority perceptions of a minority group's commitment to the larger society, we may conclude that the pursuit of inclusive nationalism is both normatively indefensible and empirically unattainable.

On the other hand, our evidence also suggests that these membership penalties are quite variable. Some members of the majority accept that there are diverse ways of belonging to Canada, including more multicultural and multinational modes of belonging, in which a commitment to Canada coexists with robust commitments to the minority's own identities and political aspirations. In that respect, the central lesson of this research, we would suggest, neither confirms nor refutes the feasibility of an inclusive nationalism, nor does it specify the outer limits of this inclusiveness in particular contexts. Rather, we hope to identify some neglected obstacles to such an inclusive nationalism and also perhaps to enrich our thinking about how narratives and practices of nationhood can either create or mitigate these membership penalties.

Shared Membership and Support for Claims-Making by Minorities

Claims-making is democracy in action. Much of what happens in democratic governance involves individuals or groups advancing claims on the state or the wider community, followed by others reacting to those claims—embracing them, rejecting them or ignoring them. To be sure, democratic discourse is not exclusively about groups advancing self-interested claims; politics is also about general societal issues, such as environmentalism. Nevertheless, a focus on specific claims represents a tougher test of the acceptance of the political agency of immigrants and various minorities within a political community. How do minority claims fare in comparison with claims originating from within the majority population?

As Bloemraad argues, claims-making is “a relational process”: people or groups make claims on others, and as a result, the “flip-side of claims-making is recognition” (Reference Bloemraad2018: 14). The key question is whether the wider society recognizes the claimant as a legitimate member of the political community, one entitled to advance claims on others. Understanding the politics of claims-making in this way requires an examination of the “processes by which people and institutions evaluate whether a claimant meets the criteria of membership” (Bloemraad, Reference Bloemraad2018: 14).

In principle, we could understand “membership” in relation to many different types or levels of community, from neighbourhoods to supranational institutions. But in the modern era, the dominant reference point for recognition of political membership is the nation. In the words of Rogers Brubaker, nationhood is “a political claim. It is a claim on people's loyalty, on their attention, on their solidarity”; it can be used to “mobilize loyalties, kindle energies, and articulate demands” (Reference Brubaker2004: 116). In Brubaker's view, the nation is simultaneously inclusive and exclusive, and “the interesting questions concern the particular ways in which ‘nation’ is used to include or exclude in particular settings” (122). Our concern is whether newcomers and national minorities are recognized as committed members of the nation and with the consequences of such judgments for the fate of claims they advance.

Given the centrality of claims-making in democratic politics, there are surprisingly few studies of claims-making to guide this enterprise.Footnote 8 Voss and her colleagues examine claims-making on behalf of undocumented immigrants in the United States, one of the paradigmatic examples of a group that is resident in a country (and often eager to naturalize) but whose members are not seen as legitimate. And indeed the authors’ analysis shows that none of the available ways of framing their claims—whether in terms of human rights, civil rights or American values—is effective in generating public support for government assistance for irregular migrants (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Silva and Bloemraad2020). There is also a small literature on another case of contested membership, namely dual citizens. Jasinskaja-Lahti and colleagues conclude that dual citizens are often seen as potentially disloyal and that this leads to reduced support for their right to make claims (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., Reference Jasinskaja-Lahti, Renvik, Van der Noll, Eskelinen, Rohmann and Verkuyten2019; Kunst et al., Reference Kunst, Thomsen and Dovidio2019). In both cases—irregular migrants and dual citizens—the obstacle to minority claims-making is not (or not only) race or religion but rather a perception that the group's membership commitment is morally compromised even when compared to others of the same race and religion.Footnote 9 These studies provide glimpses of how support for minority claims-making is shaped by membership perceptions, but there are as yet few systematic attempts to study this phenomenon.

People's response to claims-making depends not only on the group identity of the person making the claim but also on the substantive content of the claim and on the tactics used to express the claim. For example, controversies over flag burning in the United States are less about the group doing the burning than the act itself. Similarly, certain forms of civil disobedience or disruptive behaviour that are seen as threatening or raising safety concerns are less tolerated, regardless of the group protesting (Stouffer, Reference Stouffer1963; Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Sullivan, Theiss-Morse and Wood1995; Gibson and Gouws, Reference James and Gouws2000; Stenner, Reference Stenner2005; Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Crawford and Xhambazi, Reference Crawford and Xhambazi2015). Of course, evaluations or interpretations of an act or the process may well be coloured by the group performing them. When members of a group are not viewed as legitimate members of the political community, their actions are more likely to be seen as dangerous or disruptive. So questions about who is making the claim, the content of the claim and the tactics used to advance the claim will often interact in shaping perceptions about the legitimacy of the claims-making practice.

In this article, we are especially interested in whether perceptions of membership play an important and distinct role in shaping support for minority claims-making. We are also interested in whether the nature of the claim and the way in which it is advanced matter. Specifically, we ask two related sets of questions. First, to what extent does the public support the rights of immigrants and national minorities to make claims on the state or society, and how does this vary by the nature of those claims or the process through which they are advanced? Second, to what extent can perceptions of membership explain these group differences?

We seek to answer these questions by an analysis of the Canadian experience. Canada represents a fascinating case, since it is home to a complex set of ethnic and national groups, including three sets of minorities, a French-speaking substate nation, large immigrant groups characterized by a rich diversity of ethnic, religious and racial backgrounds, and the historic Indigenous peoples. These different minorities are normally seen as having quite varied relationships with the pan-Canadian community, and the country has made concerted efforts over time to build a more multicultural conception of nationhood that accommodates multiple identities and diverse ways of being Canadian. If minorities in Canada are viewed as not fully part of the shared community, similar dynamics might well be expected—and even more pronounced—elsewhere.

Data and Methods

We draw on data from an original online survey experiment of Canadians collected from August to September, 2017 (n = 2,100). The self-administered online questionnaire was fielded through Qualtrics who recruits from third-party online panel vendors. A quota system based on age, gender and education was used to screen potential respondents, which resulted in samples that reflect these measured population parameters. In addition, oversamples were collected of French-speaking Quebeckers, immigrants and visible minorities in order to allow for a sufficient sample for cross-group comparisons. The final sample includes 534 first-generation immigrants (25%); 710 French-speakers, of which 670 live in Quebec; and 773 visible minorities (37%).

Our analysis here is restricted to English-speaking Canadians that are not immigrants (n = 828). We use this group not necessarily to capture the numeric majority but rather what is viewed as a cultural, or historically dominant, majority. It has the added advantage of ensuring that when we explore the nature of reactions to minority group-based claims, members of those groups do not influence the estimate of the effect.

The heart of our analysis focuses on an embedded experiment within the questionnaire. Participants were presented with a scenario where a randomized group (Seniors, French-speaking Quebeckers, Immigrants, Aboriginal PeoplesFootnote 10) is making demands on the Canadian government. Seniors were selected as a group generally seen as deserving within society and, importantly, unlikely to activate any minority group considerations.Footnote 11 To them, we add the three salient minority groups. The scenario also varies in terms of (a) the nature of the act (a letter-writing campaign, a public protest, a street blockade) and (b) the nature of the claim (to increase funding to address poverty within their community; to do more to protect [group rights]). The act manipulation varies from a peaceful, nondisruptive act (letter-writing) to more contentious, disruptive forms of political action. Finally, we vary whether minority claims are about poverty in their group—a common problem in all groups in Canada—or whether claims are specific to the group. Here the group-specific claim varies based on the type of group and reflects current political debate (do more to protect … a Senior Bill of Rights, language rights for French-speaking Quebeckers, religious practices of immigrants, and Aboriginal land claims).

The scenarios read as follows:

Now we would like you to imagine the following situation. A group representing [GROUP] recently [ACT] in order to demand that the Canadian government [CLAIM]. Thinking about this group's demands, please tell us how much you agree or disagree with the following statements.

While in an ideal experimental set-up the group-based claim would be identical, in reality the salient types of claims made by different groups in society vary. We chose to prioritize generalizability by making believable claims by each group, but of course the differences across groups in the type of claim condition should be interpreted with caution, as part of the levels of support will be driven by the nature of the group-specific claim itself.

Participants then responded to a question on a 5-point agree/disagree scale about whether the group has the right to make such a claim (standardized from 0 to 1), where higher scores indicate more support for the right of the group to make the claim.

As noted earlier, we are interested primarily in testing two hypotheses. First, is support for minority groups lower compared to seniors? Second, if such gaps exist, do “membership perceptions” help to explain why minority claims-making is seen as less legitimate? We also explore how this gap is affected by the substance of the claim (for example, whether it is framed in more universal or group-specific terms) and by whether the act is more disruptive.

To measure what we are calling “membership perceptions,” we draw on our previous work on a membership index (Banting et al., Reference Banting, Kymlicka, Harell, Wallace, Gustavsson and Miller.2020; Harell et al. Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2021, Reference Harell, Kymlicka, Banting and Crepaz2022), which captures attitudes toward the commitment of minority groups to the larger society. We are interested in capturing the extent to which groups are seen as part of a larger political community defined by norms of reciprocity and a shared commitment to each other. The index is a seven-item measure asked separately for each group under consideration here, as well as for English-speaking Canadians. The seven items are:

• Identity: How much do you think each of the following groups identifies with Canada? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Cares: How much do you think each of the following groups cares about the concerns and needs of other Canadians? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Patriotic: How would you rate [Group] on a scale: patriotic to unpatriotic? (7-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Thankful: The government provides various programs and benefits that seek to help various communities in Canada. How thankful do you think each of the following groups are to receive these benefits? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Reciprocity: One way citizens contribute to society is by working and paying taxes. Do you think the following groups are contributing their fair share, or more or less than their fair share? (3-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Sacrifice: How willing do you think each of the following groups are to make sacrifices for other Canadians? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Fight: If Canada was involved in a war, how willing do you think people from each of the following groups would be to volunteer to fight for Canada? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

Each question is standardized on a 0–1 scale where the higher end of the scale reflects a perception of minorities as committed to the larger society and where the lower end reflects a perception of minorities as uncommitted. While there is some variation across questions based on the group under consideration (see Appendix B for details), further analysis suggests that the scales generally work very well as a single scale (Cronbach's alpha > .8 for each scale in the full sample and > .84 among the English-speaking non-immigrant sample).

Our hypothesis is that these membership perceptions matter in determining whether minority claims-making is seen as legitimate. But as noted earlier, membership perceptions are clearly not the only factor at play. We are particularly interested in two other factors that are widely seen as shaping deservingness judgments: out-group distance (where more negative attitudes drive down deservingness) and perceptions of group need (which enhances deservingness). Out-group distance is measured through a standard feeling thermometer question about social distance. Distance is measured on an 11-point scale standardized from 0 to 1, where higher scores indicate the respondent feels more distant from the interests, feelings and ideas held by members of that group.Footnote 12 This measure effectively captures more negative out-group attitudes and is a proxy for prejudice. Group need is measured by a question about whether each group is better off (0), worse off (1) or about the same (.5) as other Canadians.

As we will see, both out-group distance and perceptions of group need do matter. But our hypothesis is that even when we control for these factors, perceptions of membership commitment contribute to understanding who is most willing to recognize the claims-making rights of other groups in society. Reducing negative out-group affect is an essential step toward a more equal and inclusive society, but the social psychology literature suggests that the absence of prejudice toward out-groups does not guarantee inclusion within the in-group and the solidarity that accompanies it.Footnote 13 In-group solidarity requires some further assumptions regarding loyalty to the group and caring about its members. This is what our membership battery is intended to capture. And as we noted earlier, we suspect that membership perceptions may be particularly salient in relation to democratic solidarity, which concerns the right to shape the future of the society.

While our main focus is the relationship between membership perceptions, out-group distance and group need in shaping reactions to minority claims-making, we also include a number of other controls, including support for political protest and strength of national identity. Support for political protest is measured by level of disagreement with two statements: (1) Free speech is just not worth it if it means that we have to put up with the danger to society of extremist political views, and (2) Political protests are disruptive and should be limited. Responses were on a 5-point agree/disagree scale (Cronbach's alpha = .59). National identity is measured by the strength of one's personal identification with Canadians using an 11-point scale recoded to run 0–1, where higher scores indicate feeling closer to “Canadians in general.” Our aim, again, is to test whether the majority's evaluation of the legitimacy of minority's claims-making is not reducible to either their general attitudes toward protest or to their own strength of national identity but rather also depend on their perceptions of the minority's commitment to a national “we.” Finally, while the experimental manipulations do not require any additional controls because they are randomly assigned, we include a fuller battery of controls in models that include the membership index, as we expect respondents’ level on these variables to be in part explained by other socio-demographic variables. (See Appendix A for a full list of control variables, as well as Appendix C for details on the balance of treatment categories.)

Analysis

We begin by looking at the patterns of support for claims-making and then address the role of membership judgments in explaining these patterns.

Patterns of support for claims-making:

Table 1 presents the mean support for claims-making by treatment. Here, we are most interested in whether minority groups differ from seniors. Recall that seniors are considered a reference group likely associated with the majority and seen as deserving of various benefits. As expected, seniors’ claims-making activities are clearly endorsed at a higher level than for any of the three minority groups. Interestingly, however, claims-making by Aboriginal peoples receive a significantly higher level of support than either immigrants or French-speaking Quebeckers. These group-based differences are reproduced within the other treatments as well. We find little evidence of an overall difference between general versus group-specific claims, though respondents are less supportive of the right to make claims in more contentious ways. The protest, and especially the blockade treatment, led to lower levels of support.

Table 1 Support for Claims-Making by Treatment (raw means)

Note: Limited to English-speaking non-immigrant sample.

As noted earlier, recognition of the right to make claims likely varies based not only on the group and the nature of its claims but also on the tactic used to advance that claim. In terms of tactics, we expected letter-writing campaigns to be viewed as most acceptable and blockades to be the least, though the differences are small and only statistically distinguishable between the letter-writing campaign and blockade. All are above the midpoint, suggesting, on average, agreement with the right to make a claim—though it should be noted that it is rather tepid given that, at least for letter-writing and protests, they are unequivocally legal forms of claims-making.

These limited differences, again, hide an important underlying group-based dynamic. When presented with the innocuous letter-writing campaign, there is much greater agreement with claims-making when seniors are the group (.78) compared to Indigenous peoples (.65) and especially French-speaking Quebeckers (.53) and immigrants (.51). That 27-point gap increases to almost 35 points for the blockade scenario. In other words, group-based considerations are clearly fundamental to how claims-making is perceived by English-speaking native-born Canadians.

Figure 1 summarizes the experimental results. It presents the marginal effect of each treatment on support for claims-making based on a linear regression that includes a three-way interaction between each treatment. No other control variables are included, as the experimental manipulations are independent of respondent characteristics.Footnote 14

Figure 1 Marginal Effects of Treatment on Right to Make Claims

Note: Marginal effects based on a three-way interaction between experimental treatments. Restricted to English-speaking non-immigrants. Model on which results are based is available in Appendix D.

Figure 1 makes clear the effect of shifting from seniors to the three minority groups, which drives down support for claims-making, and the effect is particularly strong when immigrants and French-speaking Quebeckers are the claims-makers. As noted, the effects of the nature of the claim and the type of act have relatively smaller marginal effects, though these hide some underlying group dynamics, which we will turn to in the next section. This suggests that group-based considerations are heavily influencing the ways in which people are responding to these scenarios. Non-immigrant English-speaking Canadians—taken here to represent the cultural majority (if not in numbers, then in status)—tend to be more supportive of claims-making by a “deserving in-group,” namely seniors, and less supportive of claims by minority groups.

Membership and claims-making

If group-based considerations are central to understanding political solidarity, then how can we understand the types of considerations that might drive this hierarchy? Past research suggests that support for claims-making can be affected both by group distance (a central finding of research on political tolerance) and by perceptions of need and control (a central finding of research on “deservingness”). We suspect that the hierarchy observed in the previous section may be driven in part because people simply dislike a group (group affect, which drives down support) or because they view the group as in greater need for reasons beyond their control (perceptions of greater disadvantage or discrimination, which may drive up support). Similarly, we might expect the claims made by some groups to induce more sympathy. Indeed, the literature on support for redistribution points to the importance of deservingness judgments based both on perceived need and responsibility for the situation that requires help. Yet, while these may be part of the story, they cannot fully explain when people are willing to recognize the rights of other groups to make a claim. Indeed, people's willingness to recognize the rights of others “to move around the furniture” is likely also be driven by whether they are seen as full and willing members of the political community. Even in the absence of prejudice and with equal levels of need, we expect majority group members to be more supportive of claims when they consider those making the claim to be committed members of the shared community.

In Table 2, we provide an overview of how groups are viewed on these various dimensions. On affect, there is a clear in-group bias. Not surprisingly, English-speaking native-born Canadians tend to feel closest to their in-group (.17), while the other three groups score in the middle of the group thermometer. There is also some variation among the minority groups, with a somewhat greater willingness to express lower levels of affect toward French-speaking Quebeckers compared to Immigrants and Aboriginal peoples (p < .05). It should not be surprising then that we find a similar hierarchy on membership, with English-speaking Canadians evaluating themselves as more committed members. The other groups are more often viewed as (equally) less committed on average (p < .01). There is a clear view of these three groups as outsiders—the majority group respondents felt greater distance toward them and were much more likely to say they cared less and were less committed to the Canadian political community.

Table 2 Mean Group Perceptions

Note: Restricted to English-speaking non-immigrants.

The story is more differentiated for perceptions of whether each community is doing worse off than other Canadians (need) or face more discrimination. These capture more structural barriers that may induce sympathy for their demands. On need, there is recognition that Aboriginals face economic hardship (.70) and, to a lesser extent, that immigrants do (.57). French-speaking Quebeckers and English-Speaking Canadians are less distinct here, though still significantly different (p < .01). There is also recognition of the greater discrimination faced by racialized minorities, such as Aboriginal peoples and immigrants, and a clear sense that English-speaking Canadians face relatively less discrimination than other groups. In sum, the image here suggests that English-speaking non-immigrants in Canada clearly view the three groups as outsiders in the political community, despite recognition of higher levels of economic and social barriers they face.

In Table 3, we test whether these group-based perceptions can explain support for claims-making. To do so, we regress these perceptions on claims-making separately for each group we examined in the experiment (excluding seniors), while controlling for Canadian identity and general support for protest and for relevant socio-demographic variables, which may influence claims-making more generally.Footnote 15 We also include the two remaining experimental manipulations for full specification. Recall that the attitudinal variables have all been recoded to run from 0 to 1, so the unstandardized beta coefficients represent moving from 0 to 1 on these scales. The role of membership judgments stands out here. Membership perceptions are powerful, significant predictors of support for claims-making across each of the groups. When English-speaking non-immigrants see Aboriginal peoples, immigrants and French-speaking Quebeckers as members of a shared community, they are far more likely to see their claims as legitimate.

Table 3 Support for Claims-Making by Group

Note: Parentheses include t-statistic. Models limited to English-speaking non-immigrants.

* p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01

This is not to say that other variables are insignificant or behave unexpectedly. For example, group distance shows a negative effect for Aboriginal peoples and French-speaking Quebeckers, and it is in the expected direction for immigrants, though not significant. Need is a more consistent predictor of support for claims-making. For each group, greater need is significantly related to more support for claims-making. Similarly, perceived discrimination faced by the group tends to increase support for claims (though falls short of significance for Aboriginal peoples). Comparatively speaking, though, the effect size of membership is substantively larger and more consistently significant compared to other group-based attitudes. And this is not simply a problem of collinearity. While group distance and membership perceptions are correlated, as we would expect (r = .4 to .55), there is no evidence of high variable inflation factors for variables (all below 2, excluding interactions). It appears, then, that while less group affect may be a barrier to more inclusive membership perceptions, membership perceptions themselves are driving political solidarity—insofar as we can measure this through recognition of a group's right to mobilize to make a claim.

When we consider other controls in the model in Table 3, beyond the experimental treatments, we see few significant effects. National identity has no effect; those holding more negative views toward protest in general are not more or less likely to recognize groups’ rights to make a claim. There are few effects for the demographic controls, in part because of our extensive attitudinal controls. We do find a negative effect for age in the case of immigrants and French-speaking Quebeckers, and Conservatives are less supportive of the rights of immigrants to make claims, even after controlling for differences in a host of attitudes.

In Figure 2, we illustrate the effect of membership by estimating the predicted level of claims support across the membership scale. Figure 2 provides the estimated effect holding all other variables in the model constant. The reference line at .77 is the estimate of support for seniors, with a 95 per cent confidence interval.Footnote 16 Figure 2 makes clear that when the minority group is judged relatively poorly in terms of membership, support for claims-making is generally negative: respondents on average disagree that the group has the simple right to make the claim. And the gap with the average score for seniors is substantial. In contrast, on the high end of the membership perceptions scale, the difference in support for claims closes and there are no longer any substantive differences in the support of claim by group, with support for Aboriginal peoples particularly high. Clearly, membership judgments are a powerful factor in support for minority claims-making, largely closing the group-based differences we observe in our experiment.

Figure 2 Estimated Impact on Claims-Making by Membership Perceptions

Note: Predicted probabilities of support for claims-making for membership scores. Horizontal line represents the average claims-making score for seniors. Restricted to English-speaking non-immigrants. Estimates based on models in Table 3.

In sum, we have shown that recognition of the right to make claims varies substantially by the type of group making the claim. English-speaking Canadians were far less likely to agree that immigrants and French-speaking Quebeckers—and, to a lesser extent, Indigenous peoples—had the basic right to make a political claim compared to seniors. These group-based distinctions were reproduced across different types of claims and different forms of political action (despite the fact that, overall, people were less supportive of protest, and particularly blockades). We show that ingrained group-based perceptions partly account for these effects and, in particular, that membership perceptions have a powerful effect in shaping support for claims-making.

Conclusion

Claims-making lies at the heart of democratic politics. Yet our findings in Canada suggest that immigrant groups, Indigenous peoples and French-speaking Quebeckers all face group-based penalties in advancing their claims in the political process. Even though members of the groups we consider here are either citizens or are eligible for citizenship, their political claims are seen as less legitimate. While we are only able to test the types of claims made in this article (a universal claim about poverty reduction as well as group-based claims specific to salient issues for each group), we suspect that the underlying dynamic would be similar for other types of claims-making. This is an empirical question for future research.

Our findings also suggest that this failure to recognize the basic political rights of minorities is, in part, tied to perceptions that they are less committed to the larger society. These “membership perceptions” are powerful predictors of public support for the claims advanced by each group. Importantly, though, we show that when groups are perceived by the majority as being committed to the larger society, gaps in support for claims-making are reduced, or even disappear. This speaks directly to the power of membership perceptions in supporting political solidarity across historic group lines.

There are, however, fascinating differences in the membership penalties across these historic groups. We find that people tend to agree more strongly that Indigenous peoples have the right to make claims compared to immigrants and French-speaking Quebeckers, a difference that survives numerous robustness checks. An unmeasured factor is clearly driving the difference. One possibility is that there is a third set of criteria beyond humanitarian needs-based sources and membership-based sources of support for minority claims-making. While we have no measures of the recognition of historic wrongs against Indigenous peoples, future research should explore how considerations of remedial justice and reconciliation may help to underpin the majority's support of Indigenous claims. Many respondents may have been aware of the extensive public discussion in recent years about historical and contemporary wrongs relating to Indigenous peoples, and our group-based claim about land rights may have further activated such considerations. While membership is clearly a powerful predictor of support for claims-making, the fact that differences between groups remain, despite relatively similar membership penalties, suggests further research is needed.

Nonetheless, our findings point to the importance of the concept of membership. The concept draws on the literature on deservingness, which developed primarily in studies of the welfare state and the exclusion of unpopular minority groups from its benefits. Traditionally, this literature concentrated primarily on majority perceptions of the economic need of immigrants and national minorities and whether they are responsible for their own economic problems (as a result of laziness or poor life choices). The concept of membership builds beyond this focus, exploring the extent to which deservingness judgments reflect perceptions of mutual commitment. This represents a link to the literature on national solidarity, which suggests that perceptions of “we-ness” are likely to also shape public support for an inclusive welfare state. Membership has the potential to bridge the literatures on deservingness and solidarity and give us a fuller understanding of why minorities are often seen as less deserving. As we see in this article, the implications extend beyond social solidarity to inclusive forms of democratic politics.

These issues cry out for both further empirical investigation and normative reflections. Empirically, we need comparative analysis to determine whether membership perceptions play a similar role in shaping responses to minority claims-making in other countries. Are membership penalties larger or smaller in Canada compared to other countries? And this, in turn, connects to long-standing debates about the role of multiculturalism in Canada. From its origins, Canada has addressed the realities of diversity, in relation to Indigenous peoples, French-Canadians and successive waves of immigration. As a result, Canada has made efforts over time to build a more inclusive conception of nationhood that accepts and accommodates multiple identities and diverse ways of being Canadian.Footnote 17 Insofar as these efforts have been successful in shaping public perceptions, we might expect membership penalties for minorities to be smaller in Canada than in some other countries that proclaim a more unitary or assimilationist conception of nationhood. And indeed, some other evidence suggests that multiculturalism in Canada has helped immigrant-origin ethnic groups to become (and to be seen as) committed members of the nation (Bloemraad, Reference Bloemraad2012). We believe that a systematic comparative analyses of membership penalties across countries will provide an important new lens for empirically testing whether multiculturalism—or other state efforts to construct more inclusive conceptions of nationhood—in fact reduce membership penalties for minorities.

Even if an inclusive nationalism can reduce membership penalties, we are still left with the normative challenge. Why should the standing of minorities as legitimate democratic actors depend on majority perceptions of their commitment to the common society? This seems particularly inappropriate in settler states or multination states, and Canada is both. The quest of French-speaking Quebec and Indigenous peoples for greater self-government can be perceived by members of the majority as a form of disengagement with Canada, and a central task is to explore how the quest for self-government can be seen as itself a form of engagement and contribution, perhaps tied to ideas of “nested nationality.” The sources of membership perceptions are likely based in people's understanding of the historical context of groups’ inclusion within a state and current discourses about their commitment to a shared political community, as well as long-standing sources of bias and inequality. While we discuss these possibilities more elsewhere (Banting et al., Reference Banting, Kymlicka, Harell, Wallace, Gustavsson and Miller.2020; Harell et al., Reference Harell, Kymlicka, Banting and Crepaz2022), further research is needed about how people's membership perceptions are formed over time.

We cannot resolve these questions here, except to say that our evaluation of inclusive nationalism is likely to depend on what we see as the alternatives and, in particular, what are the alternative grounds for generating democratic solidarity. As we noted earlier, removing out-group animosity does not, by itself, generate solidarity, which seems to require some sense of mutual commitment to a superordinate “we.” Our findings suggest that however that “we” is defined, we need to attend to majority perceptions of minorities’ commitment to it.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) for its support of our research in the Boundaries, Membership and Belonging program.

Appendix A Variable Coding

Experimental Treatment Text:

Now we would like you to imagine the following situation. A group representing [GROUP] recently [ACT] in order to demand that the Canadian government [CLAIM]. Thinking about this group's demands, please tell us how much you agree or disagree with the following statements.

[GROUP] have the right to make such claims. (5-point agree/disagree scale).

Variables:

Membership: Membership is measured based on responses to the follow seven items which were asked about four groups: English-speaking Canadians, French-speaking Quebeckers, Aboriginals, Immigrants. The seven items are combined for each group into a single membership scale.

• Identity: How much do you think each of the following groups identifies with Canada? (4- point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Cares: How much do you think each of the following groups cares about the concerns and needs of other Canadians? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Patriotic : How would you rate [Group] on a scale: patriotic to unpatriotic? (7-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Thankful: The government provides various programs and benefits that seek to help various communities in Canada. How thankful do you think each of the following groups are to receive these benefits? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Reciprocity: One way citizens contribute to society is by working and paying taxes. Do you the following groups are contributing their fair share, or more or less than their fair share? (3-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Sacrifice: How willing do you think each of the following groups are to make sacrifices for other Canadians? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

• Fight: If Canada was involved in a war, how willing do you think people from each of the following groups would be to volunteer to fight for Canada? (4-point scale, standardized 0–1)

Group Distance: Please rate how close you feel to the following groups on a scale from 0 to 10, where “10” means you feel close to the interests, feelings and ideas held by members of that group, and “0” means you feel distant from that group. Recoded from 0 (close) to 1 (distant).

Need: In general, do you think the following groups are better off, worse off, or about the same as other Canadians? Recoded: better off (0), worse off (1) or about the same (.5) as other Canadians.

Discrimination: In general, do you think the following groups face more discrimination, less discrimination or about the same as other Canadians? Recoded more (1), same (.5) and less (0).

National Identity: The strength of ones' personal identification with Canadians using an 11- point scale recoded to run 0–1, where higher scores indicate feeling closer to “Canadians in general”.

Negative View of Protests: Support for political protest is measured by level of disagreement with two statements: 1) Free speech is just not worth it if it means that we have to put up with the danger to society of extremist political views, and 2) Political protests are disruptive and should be limited. Responses were on a 5 point agree/disagree scale (Cronbach's alpha=.59).

Other Socio-Demographic Controls:

Non-white: To which racial or ethnic group do you belong (check all that apply): White/Caucasian; Black; Asian; South Asian; Hispanic/Latino; Arab/Middle Eastern; First Nations, Inuit or Métis; Other. Recoded as 0 if White/Caucasion was selected alone, 1 if any other group was selected, alone or in combination.

Male: Are you: Male (1) Female (0)

University: What is the highest level of education that you have completed? Did not complete high school (0); Completed secondary/high school (0); Some technical, community college, CEGEP, Collège classique (0); Some university (0); Bachelor's Degree (1); Master's degree, professional degree or doctorate (1)

Income: What is your annual household income? 20k-40k (1); 40k-60k (2); 60k=80k (3); 80k- 100k (4); 100k+ (5).

Age: How old are you? 18–24; 25–29; 30–39; 40–49; 50–59; 60–69; 70+

Partisanship: In federal politics, do you usually think of yourself as… Liberal, Conservative, NDP, Bloc, Green, None of these.

Appendix B Membership Perceptions by Group

In Appendix Table B, we present mean scores for each individual item in the membership index, as well as the overall difference scores. There is a broader range of scores for Aboriginal peoples and immigrants than for French-speaking Quebeckers, suggesting some specificity to the membership criteria under consideration for each group. Furthermore, and importantly, the overall assessment of membership for each of these groups, when compared to English-speaking Canadians, is negative and significantly different than zero. In other words, each of these groups is rated lower on perceived membership than the cultural majority.

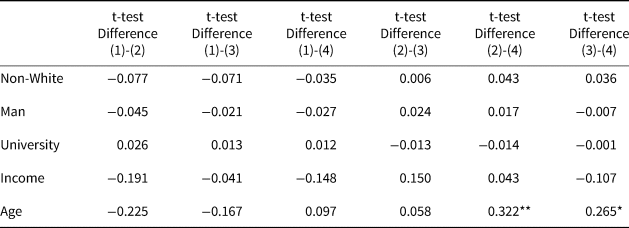

Appendix C: Balance Tests for Each Treatment

The value displayed for t-tests are the differences in the means across the groups.

***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent critical level.

Note: Sample limited to English-speaking non-immigrants (excluding those who identify as Aboriginal) in order to match sample used in analysis.