Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) has the potential to improve outcomes for long-term care (LTC) residents, their families, and the healthcare system. However, data not only suggest a need to improve ACP processes to better support Canadian LTC residents, but also that opportunities exist within Canada to identify and share best practices (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019; Heckman, Gray, & Hirdes, Reference Heckman, Gray and Hirdes2013; Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell, & White, Reference Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell and White2011).

In Canada, LTC homes provide 24-hour care and personal support to those for whom continued residence in the community is no longer feasible because of significant functional and cognitive losses, frailty, and chronic diseases (Hirdes et al., Reference Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell and White2011). More than 143,000 Canadians live in LTC homes, comprising 6% of those over 65 years of age, and 11% of those over 75 years of age (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2014a); Statistics Canada, 2012). Canadian LTC residents are, on average, 85 years of age, and an overwhelming majority have cognitive impairment (90%) and require assistance with basic activities of daily living (95%) (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019).

LTC is home to a population with increasingly high medical, nursing, personal care, and social needs. Median life expectancy of Canadian LTC residents is less than 2 years, and the risk of death is particularly high in the first 3 months following admission to LTC (Allers & Hoffmann, Reference Allers and Hoffmann2018; Hirdes et al., Reference Hirdes, Heckman, Morinville, Costa, Jantzi and Chen2019). Acute care utilization by LTC residents is high at the end of life: up to one third visit an emergency department yearly, where most undergo diagnostic tests and procedures, and one quarter are hospitalized (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2014b; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019; Stall et al., Reference Stall, Fischer, Fung, Giannakeas, Bronskill and Austin2019). A large cohort study of LTC residents in Germany showed that half were hospitalized in their final month of life, and that more than one third were hospitalized in their final week of life (Allers & Hoffmann, Reference Allers and Hoffmann2018). Critical care use is also common: a cohort study from the United States found that 20 per cent of LTC residents were admitted to a critical care unit following a visit to the emergency department, and that the use of mechanical ventilation among those with advanced dementia almost doubled from 2000 to 2013, with no gains in survival (Wang, Shah, Allman, & Kilgore, Reference Wang, Shah, Allman and Kilgore2011).

Despite such high acute care utilization, LTC residents nearing the end of life continue to experience a high burden of unmet needs and unaddressed symptoms, including pain, dyspnea, pressure ulcers, thirst, loneliness, and depression (Hoben et al., Reference Hoben, Chamberlain, Knopp-Sihota, Poss, Thompson and Estabrooks2016). A Canadian study of western LTC homes found significant symptom burden in the last year of the residents’ life, including increased behaviours related to dementia, delirium, and pain (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015). As older persons near the end of their lives, they often express care wishes focusing on quality of life, function, and symptom control, and most would prefer to die at their LTC home rather than in hospital (Rahemi & Williams, Reference Rahemi and Williams2016). Instead, they are exposed to potentially avoidable acute care visits, treatments, and iatrogenic mishaps (Stall et al., Reference Stall, Fischer, Fung, Giannakeas, Bronskill and Austin2019). Hence, the pattern of acute care utilization by older LTC residents and treatments at the end of life may be inconsistent with their care wishes.

Person-centred care should be at the forefront of care in all settings. McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2006) describe the person-centred framework as comprised of four constructs: prerequisites (the attributes of the care team), care environment (context in which care is delivered), person-centeredness processes (delivering care and services through a range of activities), and expected outcomes (as the result of effective resident centredness). The relationships among the constructs suggest that, to achieve person-centred outcomes, prerequisites, as well as the environment, should first be considered in providing effective care (McCormack & McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2006). The person-centred processes focuses on working with one’s beliefs and values and ensuring that the care team understands what the people values in their lives. This is achieved through shared decision making (McCormack & McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2006).

ACP aims to maintain person-centredness and reconcile the wishes and goals of care of persons nearing the end of life with the care that they eventually receive. ACP is a process of reflection undertaken by an individual in order to formulate and communicate wishes for future health and personal care (Hospice Palliative Care Ontario, 2018). This process is important, but particularly challenging for LTC residents, many of whom have reduced ability to personally express care wishes during a health crisis, often requiring a substitute decision maker (SDM) to do so on their behalf (Threapleton et al., Reference Threapleton, Chung, Wong, Wong, Kiang and Chau2017).

Evidence suggests that ACP interventions in LTC can decrease hospitalization rates without increasing mortality, improve the concordance of medical treatments received with resident wishes and satisfaction with the end-of-life process, reduce the number of residents dying in hospital, and potentially decrease overall healthcare costs (Martin, Hayes, Gregorevic, & Lim, Reference Martin, Hayes, Gregorevic and Lim2016; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Chichin, Carter, Burack, Lantz and Meier2005). However, few ACP interventions have been evaluated using robust trial designs, and their implementation, particularly in Canada, remains suboptimal, with more than half of residents dying in acute care settings (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019). Significant variability in outcomes, beyond clinical characteristics of residents, also exist in Canadian LTC homes with respect to hospital transfers: Ontario LTC residents are twice as likely as those in Alberta and British Columbia to be hospitalized (Hebert, Morinville, Costa, Heckman, & Hirdes, Reference Hebert, Morinville, Costa, Heckman and Hirdes2019). Moreover, 2017–18 data demonstrate significant interprovincial variability in the proportion of residents dying in their LTC home, ranging from as few as 39 per cent in Ontario to more than 80 per cent in Newfoundland and Labrador (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019). Thus, significant differences in policy and practice appear to exist across Canadian LTC homes and within provinces with respect to ACP and related outcomes.

Supported by research grants from the Canadian Frailty Network and Research Manitoba, the overarching goal of the Better tArgetting, Better outcomes for frail ELderly patients (BABEL) LTC Study is to develop, implement, and evaluate, via a cluster-randomized trial, an ACP intervention that is sustainable and scalable in the Canadian LTC sector. The following principles underlie this goal: (1) develop a multi-disciplinary ACP intervention based in evidence-informed and person-centered care, (2) deliver the intervention within existing envelopes of LTC staffing and scopes of practice, and (3) optimize the use of existing LTC infrastructure. In particular, we aim to align the intervention with the Resident Assessment Instrument-Minimum Data Set (interRAI MDS) 2.0/Long-Term Care Facilities (LTCF) instruments that are mandated in LTC homes across most of Canada, are completed at regular intervals, and provide a standardized, reliable, and validated comprehensive assessment of resident strengths, needs, and important health concerns (Heckman et al., Reference Heckman, Gray and Hirdes2013; Hirdes et al., Reference Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell and White2011). This article reports on the first phase of this work, consisting of a workshop of stakeholders from several provinces in order to identify barriers and potential shared solutions to improving ACP across all Canadian LTC homes. The findings from this work will inform the development of a standard ACP intervention that is being tested in the cluster-randomized trial.

Methods

Guiding Framework

This work is guided by the widely used knowledge-to-action (KTA) framework, which provides a rigorous approach for the development, implementation, and evaluation of a practice change intervention (Field, Booth, Ilott, & Gerrish, Reference Field, Booth, Ilott and Gerrish2014; Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, Reference Straus, Tetroe, Graham, Straus, Tetroe and Graham2009). Knowledge translation is “a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the healthcare system” (Field et al., Reference Field, Booth, Ilott and Gerrish2014; Straus et al., Reference Straus, Tetroe, Graham, Straus, Tetroe and Graham2009). This article reports on the first stage of this work, which is to select knowledge to be adapted to the local LTC context and to identify barriers to knowledge uptake, both of which were accomplished via a stakeholder workshop. The study was granted ethics clearance by the Offices of Research Ethics of the Universities of Calgary (REB17-1688), Manitoba (#HS20669), Waterloo (#31782), and Conestoga College (#CC256).

Engaging Stakeholders

Early stakeholder engagement is essential for optimizing the acceptability and feasibility of an intervention. LTC homes in each of three centres involved in this project (Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, Manitoba; Calgary, Alberta; South West Ontario) were invited to participate in the trial, and were recruited on a first-come first-serve basis until the required sample size of 24 homes had been achieved (calculations available upon request). Two representatives from each home were invited to attend the workshop based on their current involvement in ACP. Each of these provinces has a robust interRAI assessment and data tracking infrastructure, and offers variability in terms of the proportion of residents who die in the LTC homes (Manitoba 75%, Alberta 64%, Ontario 38%) (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019). Family and residents were identified by local investigators using purposive sampling and based on their ability to attend the workshop. Stakeholders were invited to a 1 day workshop to achieve the following objectives:

-

1. Share experiences and learn from the perspectives of others

-

2. Arrive at a common understanding of the key elements of person-centered ACP in LTC

-

3. Identify common barriers towards ensuring that resident wishes are properly informed and respected and strategies to overcome these barriers

-

4. Identify solutions and knowledge resources to ensure that resident wishes are understood and respected at the end of life

-

5. Identify the types of knowledge products preferred by different stakeholders

Fifty stakeholders were invited and 44 (88%) attended the workshop in person. Tables 1 and 2 describe those in attendance. One executive from an Alberta chain of LTC homes and five directors of nursing from Ontario homes did not attend: four of the latter were from a single Ontario chain, and could not attend by teleconference because of technical difficulties. However, each chain and/or homes were represented by other stakeholders. One resident and spouse (SDM) dyad, one adult child, and one adult grandchild of deceased LTC residents participated (demographics withheld because of sample size).

Table 1. Workshop attendees

Note.

a Other participants included: chief operating officer, director of quality and performance, and manager of clinical informatics.

Table 2. Demographics of workshop attendees

Note. A total of 44 participants attended the workshop from across the three provinces; this table only includes demographics of participants who completed the evaluation form at the workshop (Total n = 23, where a n = 18; b n = 19; c n = 17).

The research team includes individuals with extensive clinical (nutrition, nursing, medicine), research, and policy experience in the LTC setting and related national organizations (G A.H., A.G., V.B., H.K., P.Q.). In order to frame participant discussions, we developed a “best practice” schematic of ACP processes based on those used in published clinical trials that showed a positive impact on resident outcomes (Figure 1). This best practice is essentially the knowledge to be translated; barriers to uptake and knowledge tools needed to be developed to make this knowledge actionable (Hammes & Rooney, Reference Hammes and Rooney1998; Molloy et al., Reference Molloy, Guyatt, Russo, Goeree, O'Brien and Bedard2000; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Chichin, Carter, Burack, Lantz and Meier2005; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Wheeler, Hammes, Basque, Edmunds and Reed2002).

Figure 1. Schematic of the best practice steps in advance care planning processes in long-term care

Workshop Agenda

The workshop was held in Toronto, Ontario, Canada on September 15, 2017. It included plenary discussions framing three small group breakout sessions. Plenary sessions lasted 90 minutes each and breakout sessions lasted 25–30 minutes each. The first breakout session consisted of three groups of approximately 14 participants, while the other breakout sessions consisted of four groups of approximately 10–14 participants each. The workshop opened with the resident and family stakeholders sharing personal stories about living, end of life, dying, and ACP in LTC homes; they described both positive and negative experiences, and suggested what could have been done better. The second session, a discussion led by representatives from Hospice and Palliative Care Ontario (HPCO), reviewed processes and ethical aspects of informed consent, and how these relate to ACP. Next, attendees were divided into breakout groups to discuss and brainstorm about three of four boxes in the ACP schematic: (1) Preliminaries, (2) Framing goals within context of current health, and 3) Review, reconsider, confirm and update (Figure 1). Each breakout group was facilitated by two members of the research team, and included each stakeholder type (Table 1) and participants from each province. Breakout groups were tasked with critically reviewing their assigned “ACP box” to identify gaps and problems related to current practice, propose remedies, and make suggestions for knowledge resources that could be included in the intervention. Following the first breakout period, a third plenary was held during which the breakout groups presented their findings and a full group discussion took place. The afternoon half of the workshop consisted of two breakout sessions focused on: (1) the third box of the ACP schematic (Frame treatment options within the context of care goals), and (2) identifying knowledge translation strategies for scaling and dissemination of a potential ACP intervention. Each breakout session was followed by a plenary session in which the small groups presented their findings, followed by an open discussion. All sessions were audio recorded. In the breakout sessions, a paper method was utilized, as written notes were taken on notepads and flipcharts by members of the research team. Please refer to Appendix 1 for the meeting agenda.

Data Processing and Analysis

A thematic descriptive analysis was chosen for this study, as it is flexible and provides a rich and detailed account of the data (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Vaismoradi, Turunen, & Bondas, Reference Vaismoradi, Turunen and Bondas2013). Thematic analysis involves the search for and identification of common threads that extend across an entire interview, set of interviews, and/or discussions (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; DeSantis & Ugarriza, Reference DeSantis and Ugarriza2000). Themes were therefore identified for each session and memoranda were created using the six steps described by Braun and Clarke (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; DeSantis & Ugarriza, Reference DeSantis and Ugarriza2000). First, the investigator dyads responsible for each breakout session reviewed the audio files, flip charts, and notes to familiarize themselves with the data (Step 1). Because of the interactive dynamic and brainstorming nature of the audio files, we elected to not transcribe (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; DeSantis & Ugarriza, Reference DeSantis and Ugarriza2000). Investigator dyads worked in tandem to identify initial ideas (i.e., codes) that represented the data (Step 2). The six investigators and three research coordinators met via 11 weekly telephone conferences to discuss the emerging ideas, and searched for themes; detailed written minutes were used to summarize these ideas into initial themes (Step 3) and memoranda were used to check and elaborate the themes (Step 4). This document was maintained and shared via a cloud application that was accessible to all investigators to facilitate simultaneous review and defining and naming of themes (Step 5). Key quotes from the workshop recordings were selected to illustrate the themes (Step 6) and are attributed either to resident or family members or to LTC provider and clinicians (denoted as “Resident/SDM” and “LTC team members,” respectively). Specific identifiers and gendered pronouns were eliminated to protect the confidentiality of participants.

Findings and Discussion

We identified four themes related to adapting knowledge to the local context, including the barriers and solutions to knowledge uptake: (1) differing provincial frameworks for ACP and consent, (2) shared challenges to successful ACP processes, (3) suggesting knowledge products for LTC stakeholders, and (4) ongoing ACP conversation.

Differing Provincial Frameworks for ACP and Consent

Participants identified substantial interprovincial variability in the regulatory and ethical frameworks related to ACP and consent to treatment processes, and confirmed that these differences affected care decisions for LTC residents at the end of life. The main divergence was between Ontario and the two western provinces. In Ontario, ACP is covered by the Health Care Consent Act (Health Care Consent Act, 1996), which focuses on the expression of wishes and goals about future care. The expression of such wishes and goals is only permissible for individuals with the capacity to make informed treatment decisions. In Ontario, consent to treatment, unlike the expression of wishes and goals, can only be obtained at the specific moment a treatment decision is required. The capacity of residents for making their own treatment decisions must also be assessed at the time when a specific treatment decision is required; capacity is considered both decision and time specific. The role of the SDM is limited to providing consent for treatment when a person is incapable, and not to express wishes or goals for future care on behalf of a person who lacks capacity. Stakeholders recognized the complexity of this approach.

“You need to educate the SDMs about health care decision-making [..] but you’re also talking about educating about what’s capacity and what’s not. Those are not small pieces.”

(LTC team member)In both Alberta and Manitoba, specific treatment intentions and locations can be made ahead of time in advance of an immediate need. In these provinces, the legal delineation of care levels is tripartite: (a) no limitations on medical care interventions, (2) “medical” care only, which typically does not include resuscitation efforts, and (3) comfort care only (Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act, 2008; The Health Care Directives Act, 1992).

Although seen by participants as labour intensive, the rationale underlying the Ontario approach was described as recognizing the potential for resident wishes and goals to change over time and that predetermining a specific decision or course of action was deemed to run counter to principles of autonomy (Health Care Consent Act, 1996). Furthermore, a key challenge to consent and capacity among LTC residents is cognitive impairment from either dementia or delirium. Dementia is progressive, eroding over time the ability of a resident to make informed treatment decisions. Acute illness may cause delirium, potentially rendering a previously capable resident temporarily incapable. Therefore, as a resident’s capacity changes, it needs to be reassessed every time a decision is required. This situation is challenging in the context of LTC.

“It is imperative that health care workers and family recognize that capacity can fluctuate [as in a delirium].”

(LTC team member)Additional important differences exist across the three provinces with respect to ACP, capacity assessment, and consent. Specifically, the timing of treatment decisions varies; in Alberta and Manitoba, these can be made ahead of time, whereas in Ontario they can only be made at the time a treatment decision is required, necessitating a real-time capacity assessment. This difference has the potential to affect what type of care is received by the LTC resident at the end of life, although data are lacking in that respect. However, all participants endorsed the importance of striving for a standard approach.

“An intervention needs to be more around the principles, they key concepts that the provinces can then use and adapt into their processes.”

(LTC team member)Specifically, it was recommended by participants that any ACP intervention would need to: (1) be consistent within current local legislative and regulatory requirements, (2) provide primacy to wishes expressed by residents for their medical care, and (3) support consistent and ongoing ACP conversations among providers, residents, and families, to ensure that resident wishes are always understood.

Shared Challenges to Successful ACP Processes

Despite jurisdictional differences, participants from all three provinces identified four challenges that threaten the ability of ACP to meet the goals and wishes of LTC residents: (1) lacking clarity on the identity of the SDM, (2) lacking clarity on the role of the SDM, (3) failing to share sufficient information to inform care goals formulated by the resident, and (4) failing to communicate during a health crisis.

Lacking Clarity on the Identity of the SDM

Parties uncertain about the SDM’s identity may include the family, the resident, and LTC staff, and uncertainty may occur whether or not a single SDM has, in fact, been named. Uncertainty can be often related to disagreements within the resident’s family, or to difficulty getting in touch with family members. Sorting out this uncertainty can be complicated by an often tumultuous LTC admission process, during which there may be insufficient time for the new resident and family to develop a trusting relationship with the care team, and therefore engage in sensitive ACP and SDM discussions. As described by a provider

“End-of-life issues is hugely personal, hugely important for most people, and to have a discussion about that with people that you don’t know, who are strangers to you, and that you therefore don’t trust [..] its going to be a lot more difficult for that to be productive.

(LTC team member)Family conflict and disagreement, although not the norm, can be particularly challenging, and their existence may not be immediately apparent. Trust in the care team needs to be nurtured and developed before some residents and families will be comfortable discussing sensitive matters such as challenging family relationships and end of life. Workshop participants advised on the importance of allowing the care team to get to know residents and their families, including cultural norms, beliefs, and family dynamics and conflicts that might impact the free expression by the resident of wishes related to care. The importance of anticipating such potential obstacles and addressing them early was emphasized. For example, one participant stated

“[The] kids took a longer time to start realizing that [they] would not walk after [the] stroke – kids are very emotional, it takes a long time for things to sink in.”

(Resident/SDM)Lastly, many participants expressed being confused by the different terminologies and levels of influence for SDMs. This included distinguishing the term “SDM” from Power of Attorney for financial issues. Some acknowledged that such confusion would at times lead them to defer starting ACP conversations with residents and their families, even at times when health circumstances were such that these would have been beneficial.

Lacking Clarity on the Role of the SDM

There is consensus in Canada that the role of an SDM is to help the health care team understand what care the resident would (or would not) want in a given circumstance when she/he has lost capacity, temporarily or permanently (Teixeira et al., Reference Teixeira, Hanvey, Tayler, Barwich, Baxter and Heyland2015). Participants endorsed the importance of this role but noted that sometimes the process prioritizes SDM wishes over the presumed wishes of the resident. This distinction is often not understood by residents, SDMs, families, and even LTC caregivers. A salient example is that numerous care team members report that when asking an SDM about resident care wishes, they often frame the question as: “What do you want us to do?” rather than “What do you believe [the resident] would want us to do in this situation?”

“You want a plan that works for you – not what your family wants – especially in an emergency.”

(Resident/SDM)“Residents need to know [..] just because you have a power of attorney you don’t need a SDM if you can make your own decisions.”

(LTC team member)Participants also noted that LTC teams must be prepared to help residents and SDMs navigate a number of potential related pitfalls. First, to avoid future confusion and conflict, the resident’s wishes and preferences and responsibilities of the designated SDM should be understood by other family members and friends (and the care team). Second, residents and SDMs should be made aware that capacity to make decisions can depend on the complexity of the treatments being considered, as well as on the severity of the dementia or delirium. Some participants expressed that LTC teams need to maintain a high index of suspicion that the wishes expressed by residents could result from coercion, subtle or otherwise, imposed on them by SDMs or other family members, ensuring that all parties explicitly be made aware that treatment decisions should reflect the resident’s wishes, and not those of others. As noted by these stakeholders

“If you have their wishes written out, or whatever, you can say to the SDM: You’re acting on behalf of that person, this is what they said, just to remind you …You’re not deciding for you, you decide for this person.” ID].

(LTC team member)“Initially, I was not going to pull the plug, but now I know they have made their decisions.”

(Resident/SDM)It is critical that all LTC stakeholders, including residents and SDMs, understand that the SDM role is to fully understand the resident’s wishes, preferences, and goals of care, and that these should they be called upon to make a treatment decision should the resident be incapable. SDMs must, therefore, be fully involved in ACP conversations.

Failing to Share Sufficient Information to Inform Care Goals Formulated by the Resident

Resident and family participants emphasized that most LTC residents understand, in general terms, that they are nearing the end of life and wish to know what to expect (Sharp, Moran, Kuhn, & Barclay, Reference Sharp, Moran, Kuhn and Barclay2013). A number of resources (i.e., pamphlets, booklets, Web sites) are available to them, and those who have taken the time to read these have found them to be helpful, at least in a general way (Advance Care Planning Waterloo Wellington, 2015; Alberta Health Services, 2019; Speak Up Canada, 2019):

“In my experience, I find that [residents] are not resistant to having the conversation. The conversations are happening. So what I find is that our residents and families aren’t prepared because they weren’t having the conversations…”

(LTC team member)However, it was clear from discussions that the most important gap in resident/SDM information needs relates to understanding the individual resident’s current health status, prognosis, and medical options. Because of the wide range of medical challenges experienced by LTC residents, there is no simple, universal way to transmit this information, which was deemed essential to formulating realistic goals and wishes. Participants identified two key causes of this gap. The first is the limited discussion of medical care details and prognosis during ACP conversations. This was felt to result from: (1) limited or no physician involvement in ACP discussions held in many LTC homes, and (2) the fact that the LTC care team who generally leads ACP discussions – consisting of nurses and social workers – is often uncomfortable addressing medical details and prognostication for non-malignant conditions. Further, prior to LTC admission, residents and families are often in possession of health and prognostic information that is misunderstood, incomplete, or even incorrect.

“It’s their understanding … We’re asking them to define…goals; do they really know the trajectory? What is going to happen?”

(LTC team member)“From a nursing perspective there’s sometimes a challenge supporting other decisions that were made…because you don’t know what the information was.”

(LTC team member)Several potential solutions to addressing these barriers were offered. The first is paying attention to the specific medical conditions and prognosis of the resident. This not only includes addressing these during ACP discussions, but also educational support and resources for residents, families, and LTC home staff. The focus of these resources would be to aid in understanding and clearly communicating the most likely health trajectories of chronic disorders and syndromes common among LTC residents, such as dementia, Parkinson’s disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, and frailty. It was noted by a provider that

“Mom may have been like this a year [ago] but here’s who she is now. It’s helpful when [physicians] are comfortable to propose that treatment plan, to say “Here’s what we can do for mom; here’s what we can’t do for mom.”

(LTC team member)Second, participants identified clinical scenarios and treatment options, beyond cardiopulmonary resuscitation, that care teams should be better prepared to discuss. Guidance regarding whether or not a resident should be transferred to a hospital can be insufficient. Simple binary decisions to not transfer lack nuance; although residents may wish to forego care that they consider too aggressive, they might accept hospitalization for relatively minor problems that cannot be addressed in the LTC home (e.g., skin laceration or a fracture). A need for better training and more nuanced discussions was identified with respect to the prescription of antibiotics (e.g., distinguishing their use for a simple urinary tract infection vs. use for recurrent aspiration pneumonia related to progressive Parkinson’s Disease), interventions to support hydration and nutrition beyond feeding tubes, initiation or cessation of dialysis, and whether diagnostic testing would meaningfully alter the expected health trajectory. Third, care teams should consider sharing the results of routine assessments with residents and families, and be able to explain these in lay terms, avoiding medical abbreviations and jargon. Participants were unanimous that all decisions should be guided by the resident’s preferences, wishes, and values, and that residents (and their SDMs) need to have sufficient knowledge of their medical situation and prognosis to make informed decisions about the interventions that are most likely to be offered. As noted by this stakeholder

“Right now I have a good life – but if I start suffering, I don’t want to be kept alive. I do not want CPR, life support, dialysis, or a ventilator. I don’t want anyone to keep me alive when my time comes. I do want medication to relieve pain and I want oxygen. I prefer to die at [LTC home]. And near death, I want to look at family pictures.”

(Resident/SDM)Thus, participants stressed the importance of LTC homes adopting a proactive approach to ACP, and providing health information that is specifically relevant to the resident’s conditions, in order to best inform any wishes related to treatment decisions.

Failing to Communicate During a Health Crisis

Acute medical emergencies in LTC residents are unpredictable, often occurring during nights and weekends when staffing is reduced. Participants identified that residents and SDMs are insufficiently prepared, including emotionally, for the rapid decision making that occurs during a health crisis. For example

“It’s preferable not to do ACP in a time of great stress…because stress is a very powerful influence on decision-making.”

(LTC team member)This view is supported by literature indicating that under such stress it is not uncommon for SDMs to choose aggressive care that reverses prior decisions (Pulst, Fassmer, & Schmiemann, Reference Pulst, Fassmer and Schmiemann2019; Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Halifax, Bui, Lee, Harrington and Shim2015). Furthermore, the SDM may not have been updated about recent declines in the resident’s health trajectory. Education alone cannot prepare an SDM for the stress and anxiety associated with making emergent care decisions for a resident who does not have the capacity to do so. As a result, SDMs may forget that their role is to frame health care decisions based on resident wishes, and instead impose their own biases.

Another important concern relates to the nature of physician coverage in LTC, which was described as often suboptimal, with emergent triage decisions frequently made by cross-covering physicians unfamiliar with the particular resident. As observed by a provider

“The times we get tripped up…is in the emergency situation. Something changes, and someone wasn’t prepared, and it’s an on-call doctor, it’s a casual nurse, and then we’re just doing the safe option, we’ll do the intervention.”

(LTC team member)Unless the resident’s level of care is clearly recorded as being “comfort care only” this very often results in defensive decisions to transfer the resident to an emergency room or hospital, regardless of nuanced decisions made at prior ACP conversations, of which cross-covering physicians usually have no knowledge. This is compounded by frequent lack of accessibility to relevant documentation of resident preferences and wishes, particularly overnight or when on-call or casual staff are not familiar with the resident or family.

Although participants emphasized the importance of thorough conversations and preparation prior to a health crisis, conversations based on hypothetical scenarios were deemed potentially problematic, with the conceptual leap to real-life, resident-specific concepts being difficult, especially in an emergency. Additional concerns included clinicians being perceived as applying undue pressure on residents and families, such as emphasizing the more frightening and gruesome aspects of interventions, particularly cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

“We were asked six times to change the DNR status and staff used different tactics for us to change our mind – the scare tactic – the gory tactic – the guilt tactic”

(Resident/SDM)Finally, the choice to remain in the LTC home is often perceived by residents and their families as “doing nothing”, which can exacerbate underlying fears of pain and suffering. Part of the needed preparation for emergencies is that residents and families must be reassured that LTC homes will provide excellent symptom control in a familiar and comfortable environment to the resident and the family. As such, it was recommended that “comfort care” should be appropriately explained as an active intervention rather than as a passive default, or worse, abandonment. As mentioned by a provider

“It also goes back to knowing what the resident truly wants when fear comes into it, because am I going to support you in your wish to stay here for the end-of-life?”

(LTC team member)More generally, the care team should be prepared to support residents, SDMs, and families at such difficult times. Having the SDM involved in prior ACP conversations with the resident, and having easily accessible, clear and up-to-date documentation of a resident’s wishes for care are important to facilitate this support. LTC teams should anticipate the residents’, SDMs’, and families’ fear and stress; have conflict resolution skills to advocate for the resident’s best interests, preferences, and wishes; and help SDMs and families navigate and cope with these processes. As voiced by a resident representative

“Mom [with severe dementia] had a heart attack [and ] was moved to ICU. In retrospect I rather would have kept her in the home. She returned to LTC. I did not make the right decision, but my sister might not agree. It would be better to have better explained options for family for these crisis situations.”

(Resident/SDM)Therefore, participants considered it essential that ACP conversations ensure that residents and SDMs be properly supported during a medical emergency, in order that the care wishes and goals of the resident be respected.

Knowledge Products for LTC Stakeholders

All participants recognized that an ideal ACP conversation considers resident care preferences, wishes, and health status. Therefore, participants proposed that knowledge products should be designed to foster better conversations and information exchange.

Resources for Residents and Families

Existing ACP documents were considered very informative by all attendees, including residents and families. However, these resources are generally lengthy, expensive, or available only in limited quantities, whereas shorter documents, such as pamphlets and posters, or electronic apps were suggested as a means of engaging a broader audience. Additional unmet needs include: (1) disease- or health-condition-specific information, perhaps in coordination with chronic condition societies (e.g. Heart and Stroke Foundation, Alzheimer’s Society), and (2) respectfulness across cultures and beliefs.

“[Regarding an ACP video]: Was helpful, but not tough enough. Was missing “when I am going to die” – the responsibility lies with the person who has to make the choice.”

(Resident/SDM)“When the people come to LTC, maybe they should be given handouts about all this information.”

(Resident/SDM)“depending on what generation they’re at they might need something different. And also cultural, and we also have a spiritual guide as well on what some spiritual beliefs are because it really depends on what they follow and what their needs are.”

(LTC team member)In addition to static documents, many participants endorsed that interactive learning opportunities should provide more in-depth understanding of complex ACP and SDM issues, such as family classes or discussion groups for residents, and communities of practice for clinical staff.

Products for Health Care Workers

Participants identified the need for: (1) more clinically oriented learning opportunities, such as case-based discussions and train-the-trainer opportunities, and (2) greater clarity related to interprofessional roles, particularly more integrated nursing and physician involvement. Pocket cards and brief posters with point-of-care algorithms were proposed to support care teams navigating health crises. It was noted that any knowledge products created would have to be compatible with provincial regulations. Greater education for all with respect to understanding relevant interRAI measures (e.g. health stability), and how to describe the prognosis and trajectory of specific conditions were also considered important.

Ongoing ACP Conversation

Participants all emphasized that care processes should be established to allow for ongoing ACP conversations, and suggested several triggers for resuming these. Triggers suggested included:

-

1. when the LTC care team observes a change in the resident’s condition, function, or cognition

-

2. at a time of deterioration or exacerbation of an existing chronic condition or when a supervening acute condition occurs

-

3. when requested by the resident

-

4. at regular reviews (e.g., yearly) for otherwise stable residents

There was agreement among participants that the resident’s voice must remain central to any conversation about care wishes and goals, even if the resident is ultimately deemed incapable to consent for a related treatment decision.

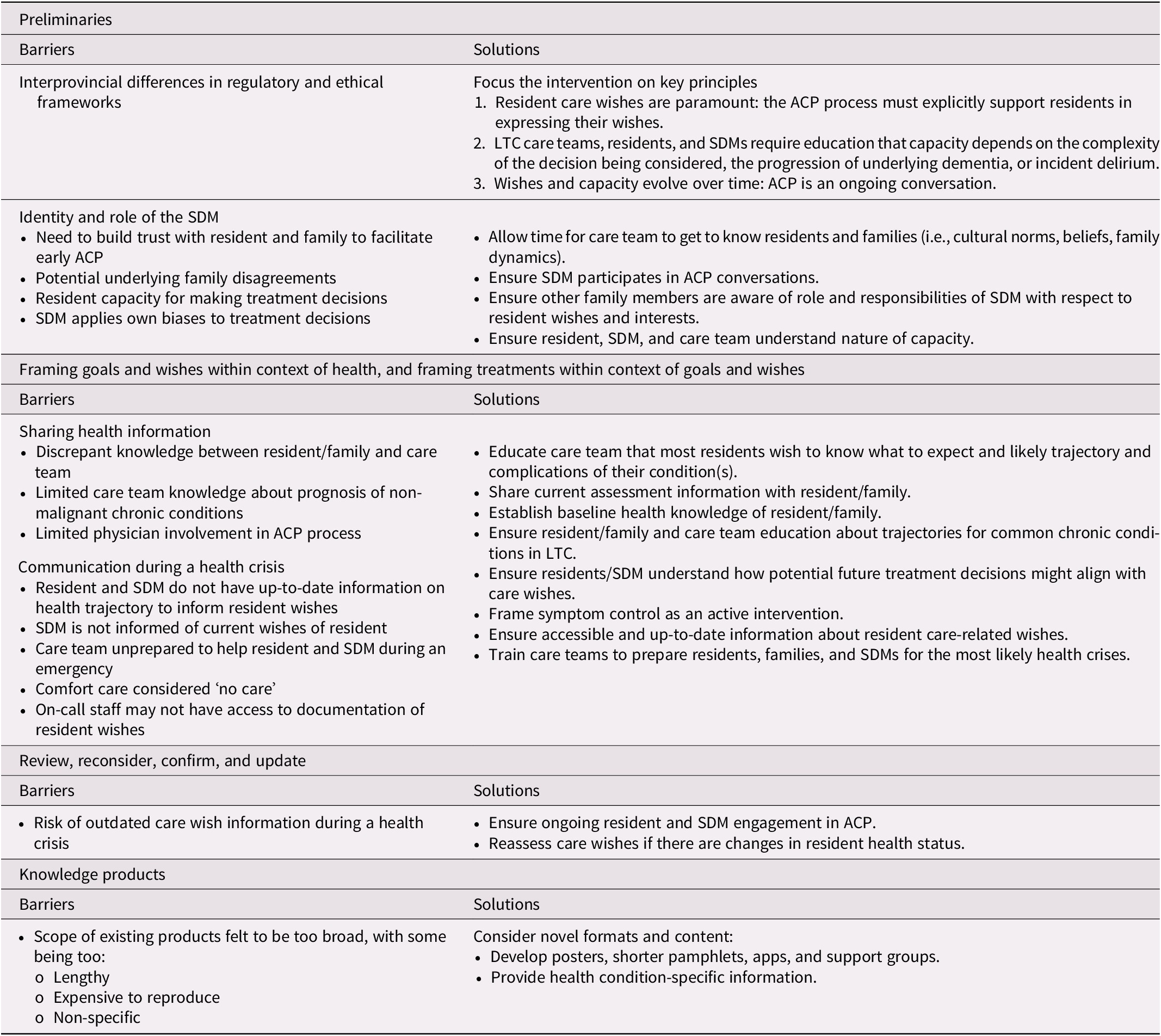

The participant-suggested solutions to identified barriers for the four step model (Figure 1) are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Stakeholder suggestions to address barriers to advance care planning (ACP)

Note. LTC = long-term care; SDM = substitute decision maker.

Conclusion

The stakeholder workshop identified several key considerations related to the future implementation of a national ACP strategy for residents in LTC. Notably, important differences among provincial regulatory and ethical frameworks must be taken into account and reconciled. Shared challenges include lack of clarity on the identity and role of the SDM, and communication difficulties related to the sharing of resident-specific health information to guide the formulation of care goals, and during a health emergency. Participants suggested a need for simpler and practical knowledge products to complement existing resources, which although useful, were considered lengthy.

An important theme running through the concepts discussed by the participants is that of time. Appropriate ACP requires time – time to establish trust and open communication among the resident, family, and care team; time to understand the health issues faced by the resident; time to educate; and time to assess capacity and discuss care wishes – all in order to stay person-centred so that residents make the best decision for themselves. McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2006) describe how person-centred care should result in satisfaction with care, feeling involved, and feeling as though decision making is shared and that there is a collaborative relationship. Residents should feel involved and engaged, and the care team should maintain a sympathetic presence and work with the resident’s beliefs and values in mind (McCormack & McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2006). Participants emphasized how the admission process to LTC is tumultuous and fraught with anxiety and stress, leading to delayed and incomplete ACP discussions. In contrast, recent Canadian data emphasizing high mortality and hospitalization rates in the first 3 months after admission to LTC suggests that, at least for some residents, excessive delays to ACP conversations may lead to unnecessary acute care utilization. Therefore, mechanisms to identify residents at highest risk of an early health event and prioritizing ACP conversations may be required. Potential targeting mechanisms could include certain diagnoses (e.g., heart failure) or interRAI indicators (e.g., Changes in Health, End-stage Disease, and Signs and Symptoms [CHESS], “leaving 25% food uneaten”) (Heckman et al., Reference Heckman, Hirdes, Hebert, Morinville, Amaral and Costa2019; Tjam et al., Reference Tjam, Heckman, Smith, Arai, Hirdes and Poss2012). Additional stakeholder engagement is required in order to understand how best to implement such a strategy without compromising the effectiveness of ACP conversations.

The stakeholder engagement workshop on ACP was helpful to identify many common barriers faced by LTC teams across Canada and potential solutions, despite differences among provinces in approaches to consent and capacity. Although these differences should ideally be reconciled, participants were able to agree on principles that, if adhered to, would improve the quality of ACP conversations and processes. That said, a number of limitations to this work are to be noted. First, ACP is fundamentally a matter of understanding the lived experience of residents and family members, whose numbers at the workshop were small. The logistics of transporting and housing frail individuals to lengthy meetings, for which many lack stamina, is challenging. The lack of representation of frailer residents is therefore a limitation, although the family member stories offered a range of perspectives and experiences reflecting more frail residents, and encompassed both positive and negative aspects of ACP and end-of-life care. The approach to the recruitment of residents and family members by the research team may have predisposed to a social desirability bias. However, this risk was likely minimized, as the majority of time spent by these participants was with other workshop participants and not the researchers. Second, few physicians participated in the workshop, and participants noted that physician participation in ACP conversations can be suboptimal. Lack of time and knowledge have been identified as barriers to physician involvement in ACP (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Bernard, Klein, Elston, Tan and Slaven2018). Physicians have an important role in providing residents and families with information on diagnoses, disease trajectories, and treatment options and impacts. Increasing physician engagement in the development of ACP interventions and conversations is a priority. Third, not all Canadian provinces and territories were represented at the workshop. Specifically, northern, Indigenous, and immigrant populations were not represented, and neither were Quebec and the Atlantic provinces. However, Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba are representative of the wide range of rates of mortality of residents outside the LTC home (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019). Moreover, they have all implemented a robust interRAI assessment infrastructure necessary for scaling an eventual ACP intervention to the entire country (Heckman et al., Reference Heckman, Gray and Hirdes2013; Hirdes et al., Reference Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell and White2011). Fourth, the results of the workshop were not shared with participants as a form of member check, as a clinical trial had been planned, and there was a concern about potential contamination of potential control homes (Shenton, Reference Shenton2004).

The involvement of stakeholders in an in-depth structured workshop succeeded in providing important insight into how to improve ACP conversations and how to do this in a manner potentially scalable to virtually the entire country, reiterating the importance of integrated knowledge translation as emphasized in the KTA framework (Straus et al., Reference Straus, Tetroe, Graham, Straus, Tetroe and Graham2009). The next steps in this project are to continue to engage with stakeholders to develop an ACP intervention and knowledge products, and to conduct a randomized cluster trial to evaluate its impact on care received and concordance with wishes at end of life (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03649191).

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980820000410.