Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are among the most stigmatized illnesses globally (Alzheimer Disease International, 2012; Mitchell, Dupuis, & Kontos, Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Kontos2013), leading to social exclusion, isolation, and reduced quality of life for persons living with dementia and family or friend care partners (Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova, & Liu, Reference Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova and Liu2015). A diagnosis of dementia often results in less frequent interactions with family and friends, and changes in social roles and activities for both persons living with dementia and their care partners (Førsund, Skovdahl, Kiik, & Ytrehus, Reference Førsund, Skovdahl, Kiik and Ytrehus2015; Hemingway, MacCourt, Pierce, & Strudsholm, Reference Hemingway, MacCourt, Pierce and Strudsholm2016; Hennings & Froggatt, Reference Hennings and Froggatt2019; Høgsnes, Melin-Johansson, Norbergh, & Danielson, Reference Høgsnes, Melin-Johansson, Norbergh and Danielson2014; Shanley, Russell, Middleton, & Simpson-Young, Reference Shanley, Russell, Middleton and Simpson-Young2011). With the emergence of COVID-19 and the public health measures instituted to control the spread of the virus, the potential impacts on these already isolated groups are profound (Livingston & Weidner, Reference Livingston and Weidner2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Barbarino, Gauthier, Brodaty and Molinuevo2020).

Across Canada, provinces have mandated a range of closures and restrictions on non-essential services during the first year of the pandemic (e.g., Government of Alberta, 2021; Government of British Columbia, 2021; Ontario Ministry of Health, 2020). For persons living with dementia in the community, this has meant that they have not been able to attend many of the programs and services that they typically do (such as day programs, support groups, and leisure activities) or have had to shift to online participation where available. The availability of in-person and online supports and services for persons living with dementia has varied greatly across the country. For example, in Ontario, access to day programs was reduced, although some support groups transitioned online. However, in some provinces, support groups for persons with dementia did not transition online and in-person programming was suspended, leaving significant gaps in services and supports for persons living with dementia. To address these gaps, many care partners have needed to step in to support persons living with dementia. Depending on the needs of the individual, this may include (increased) support with purposeful activities such as exercise, leisure, socialization, and spirituality, as well as assistance with activities of daily living, such as eating and bathing. At the same time, closures or restrictions of non-essential services as well as physical distancing requirements have impacted care partners’ own support networks (e.g., respite, support groups, friends) which may no longer be available, available only online, and/or significantly reduced (Government of Alberta, 2021; Government of British Columbia, 2021; Ontario Ministry of Health, 2020).

Because COVID-19 only emerged a little over a year ago, it is not surprising that relatively little is known about the impacts of the virus and the associated public health measures on persons living with dementia. However, given the potential risk to the well-being of persons living with dementia, it is imperative that research focus on this population. Indeed, calls for research to better understand the impact of COVID-19 on those affected by dementia have been made (e.g., Barros, Borges-Machado, Ribeiro, & Carvalho, Reference Barros, Borges-Machado, Ribeiro and Carvalho2020; Editors of Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 2020; Greenberg, Wallick, & Brown, Reference Greenberg, Wallick and Brown2020). This research will serve to deepen our understanding of the current state of affairs and inform the development of appropriate supports for the remainder of the pandemic and beyond.

Of the research that has been conducted on the impact of COVID-19 on the well-being of persons living with dementia, only a handful of studies have sought to collect data directly from persons living with dementia. A qualitative study (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley and Gaughan2020) involving in-depth interviews of persons living with dementia and care partners was undertaken to explore the impact of social support service closures. This study was conducted in April 2020, soon after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Fifty interviews were conducted (42 with care partners and 8 with persons living with dementia). However, the data were not analyzed separately for each group, making it challenging to understand the specific impacts to persons living with dementia. Another qualitative study by Portacolone et al. (Reference Portacolone, Chodos, Halpern, Covinsky, Keiser and Fung2021) engaged 24 older adults living alone with cognitive impairment in San Francisco to gain a deeper understanding of their lived experiences of the pandemic. This work sought to understand how older adults living alone with cognitive impairment were coping during the pandemic, including their priorities, concerns, and needs for supports and services. Interviews were conducted at least twice by phone between April and July 2020. Participants identified feeling scared, facing extreme isolation, and experiencing challenges with misinformation about the pandemic. They also emphasized their access to necessary supports and services as being essential to meeting their needs.

In a qualitative study by Roach et al. (Reference Roach, Zwiers, Cox, Fischer, Charlton and Josephson2021) in Calgary, Alberta, interviews were conducted with patients and their care partners from a cognitive neuroscience clinic between April and May 2020 to examine the impact of the pandemic on the health and well-being of persons living with dementia. Of the 21 participants, only 1 was a person living with dementia. Three themes described the personal, health service, and health status impact of the pandemic, and highlighted the challenges associated with social isolation. Studies have also examined COVID-19’s impact on the health and health care of persons living with dementia (e.g., Canevelli et al., Reference Canevelli, Valletta, Toccaceli Blasi, Remoli, Sarti and Nuti2020; Caratozzolo et al., Reference Caratozzolo, Zucchelli, Turla, Cotelli, Fascendini and Zanni2020; Tsapanou et al., Reference Tsapanou, Papatriantafyllou, Yiannopoulou, Sali, Kalligerou and Ntanasi2021).

Two quantitative studies were also identified, from Giebel et al. (Reference Giebel, Lord, Cooper, Shenton, Cannon and Pulford2021) and Goodman-Casanova et al. (Reference Goodman-Casanova, Dura-Perez, Guzman-Parra, Cuesta-Vargas and Mayoral-Cleries2020). Both undertaken in early 2020, the surveys examined access to social services during the pandemic and how service closures impacted well-being (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Lord, Cooper, Shenton, Cannon and Pulford2021), as well as the impact of stay-at-home orders (confinement) on health and well-being (Goodman-Casanova et al., Reference Goodman-Casanova, Dura-Perez, Guzman-Parra, Cuesta-Vargas and Mayoral-Cleries2020). The study by Giebel et al. (Reference Giebel, Lord, Cooper, Shenton, Cannon and Pulford2021) found that not being able to access support services predicted higher levels of anxiety among persons living with dementia. Variable service availability was not predictive of depression or well-being. In the study by Goodman-Casanova et al. (Reference Goodman-Casanova, Dura-Perez, Guzman-Parra, Cuesta-Vargas and Mayoral-Cleries2020), participants indicated whether their mental health and well-being were: well, calm, sad, worried, afraid, anxious, and/or bored. Sixty-one per cent of participants reported being “well”; 29 and 24 per cent reported being “sad” and “anxious”, respectively. However, the proportion of the 93 people interviewed in this survey who were living with dementia was not reported.

The studies reviewed indicate that relatively little research published to date has explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health measures on the well-being of persons with dementia, and even less research has included the voices of persons living with dementia. The findings related to COVID-19’s impact on well-being are mixed, although with so few studies and the use of a variety of methods, including different foci of investigations, it is difficult to draw conclusions. Further, all of the literature reviewed was conducted during the first few months following the World Health Organization’s declaration of a global pandemic and may not provide the full picture of how public health measures have impacted persons living with dementia.

Given the many ways that COVID-19 has upended the lives of persons living with dementia, we wanted to hear directly from persons living with dementia about how COVID-19 has affected their psychological, social, and physical well-being. In this study, “well-being” is defined broadly and includes an individual’s subjective perceptions of the psychological, social, and physical aspects of their life (George, Reference George2010; Kaufmann & Engel, Reference Kaufmann and Engel2016). We also wanted to understand the perspectives of persons living with dementia during the pandemic, after they had experienced changes in their lives for at least 6 months. Thus, the purpose of this qualitative analysis was to explore the perceptions of persons living with dementia about how COVID-19 has affected their well-being after the first 6 months of the pandemic.

Methods

Design

This intrinsic case study was part of a larger research project which aimed to: (1) understand how COVID-19 affected the daily lives and social connections of persons living with dementia and care partners of persons living with dementia, and (2) identify technological and other creative strategies used by persons living with dementia and care partners to remain connected and support each other. The overall study used an intrinsic case study design (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013) with mixed methods (surveys and interviews). Intrinsic case study designs are appropriate when the aim is to understand a unique phenomenon, one that is intrinsically interesting (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013): in this instance, how COVID-19 has affected the well-being of persons with dementia and care partners. Although the project collected both survey and interview data across care partners and persons living with dementia, this article focuses only on the interviews with persons with dementia living in the community and their perceptions of how COVID-19 has affected their well-being.

Sampling and Recruitment

Participants included persons living with dementia (self-reported) residing in the community anywhere in Canada. Purposive and snowball sampling were used to recruit participants. Study information was distributed broadly through newsletters, Web sites, and social media accounts of partner organizations who were supportive of the study. In addition, individuals who consented to participate were asked if they knew of other individuals living with dementia who might be interested in participating and were invited to share the study information with those individuals.

We conducted interviews with 10 individuals living with dementia. The time since diagnosis ranged from less than 1 year to 21 years, with an average of 9 years. One individual did not provide demographic information. Of those who did, five were men, three were women, and one preferred not to answer. Participants ranged in age from 56 to 79 years (average of 66.9 years); five were from Ontario, three were from British Columbia, and one was from Alberta. Four participants reported that they lived alone and four lived with their spouse. One participant had recently moved into long-term care but was very interested in participating. Not wanting to exclude this person’s voice, we welcomed the person into the study.

Data Collection

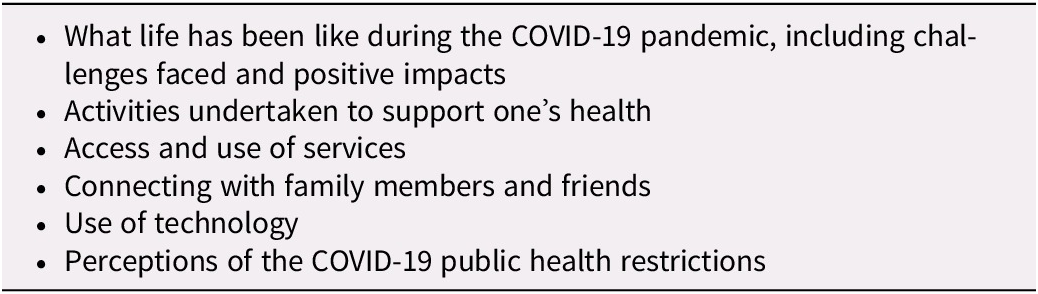

Persons living with dementia were provided with three options for participating. They could (1) complete a survey only, (2) complete a survey and participate in an in-depth interview, or (3) participate only in an in-depth interview. Based on the preference of each individual, surveys were completed independently or with the support of a trained research assistant by telephone or through an online platform. Active interviews (Holstein & Gubrium, Reference Holstein and Gubrium1995) were used to explore participants’ perceptions regarding the impact of COVID-19 on their well-being. To help participants feel comfortable, interviews were conducted either online or by phone, based on the preference of the participant. Interview guides were informed by the literature and the expertise of the research team and project partners (see Table 1 for topics explored during the interviews). To help build rapport, interviewers began each interview with a few introductory questions. Participants were also invited to add any additional comments about the impact of COVID-19 at the end of the interview. Interviews were conducted between September 2020 and February 2021. The interviews lasted an average of 32.4 minutes, ranging from 13.2 to 59.3 minutes. Four individuals were interviewed by phone, and the remaining six were interviewed through an online platform.

Table 1. Topics explored during the interviews

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim, cleaned, and anonymized. The inductive thematic analysis was conducted by three members of the research team (C.M., E.C., M.K.) following the six-step process outlined by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Thematic analysis has been identified as an appropriate analytical approach in intrinsic case study designs (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013). An iterative process was used to conduct the analysis, with the three research team members independently coding one transcript, meeting to identify the initial coding framework, using the framework to code the remaining transcripts, and meeting to review the final codes and relevant extracts and develop themes. After the themes were defined, the findings were compiled and shared with the rest of the research team for review and assistance with interpretation. Exemplar quotes are provided in the Findings to support the themes and subthemes. An identification code follows each quote to indicate the participant from whom the quote came. NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) was used to support data coding and analysis.

Methods to Enhance Rigour

We used a number of strategies to enhance rigour (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). To promote credibility, two researchers were involved in conducting the interviews, which ensured that they stayed “close to the data” during the analysis. In addition, the three researchers involved in data analysis engaged in regular peer debriefing. To promote dependability, a detailed description of the study methods and analysis were provided. Researcher triangulation and the use of quotes to support the themes and subthemes helped to promote confirmability. Transferability was promoted by providing a thick description of the research methods and the findings.

Ethical Considerations

The study was reviewed and received joint ethics clearance from the University of Waterloo and Conestoga College (ORE# 42189) and from the Sheridan College Research Ethics Board (SREB N° 2017-03-001-005). Because data collection was required to take place virtually (by phone or online) due to COVID-19 restrictions, the study information and consent form were sent to potential participants prior to their scheduled interviews. In advance of the interview, the interviewer reviewed the information and consent form with the participant, asking questions to ensure their understanding of what was involved in participating in the study. If the individual understood the study and what was required to participate, verbal consent was obtained. At the time of the interview, verbal consent was obtained a second time. If the individual was not able to demonstrate that they understood the study and what was required to participate, proxy consent was sought. In this study, all participants were able to provide verbal consent without a proxy. In some cases, it was not possible to schedule a time to review the information and consent form a few days prior to the interview. In these instances, the information and consent forms were reviewed at the time of the interview, following the same consent procedure described.

Findings

The thematic analysis identified four broad themes: (1) Expressing Current and Future Concerns, (2) Social Connections and Isolation, (3) Adapting to Change and Resilience through Engagement and Hope, and (4) We’re Not All the Same: Reflecting Individual Experiences of the Pandemic.

Expressing Current and Future Concerns

The theme Expressing Current and Future Concerns related to life during the pandemic was prominent in the interviews conducted with persons living with dementia. Within this theme, two subthemes were identified: Worries and fears about physical, cognitive, and social well-being of self and others and Frustrations with life changes and restrictions. Persons living with dementia highlighted both the fears of living during the pandemic, including worries about one’s own cognitive abilities and health, and the health and well-being of friends, family, and other persons living with dementia. The frustrations of having to be physically distanced from loved ones and experiencing significant restrictions from accessing needed supports and services were also highlighted.

Worries and fears about physical, cognitive, and social well-being of self and others

The subtheme of Worries and fears about physical, cognitive, and social well-being of self and others encompassed instances in which participants discussed their fears, concerns, and worries related to being exposed to or contracting the COVID-19 virus. Participants also discussed worries and fears in relation to social factors, such as keeping up relationships and maintaining connections, as well as fear for the well-being of others living with dementia. In particular, participants expressed concern for persons newly diagnosed with dementia and individuals who were living alone without a support system.

Participants described being “nervous” or “paranoid” when asked about their thoughts and feelings during the pandemic. They linked their experience with dementia to their unwillingness or caution in going out into the community, stating:

“I personally will not go out of the house, because I think if I get it, and it affects the O2 level in my blood, what’s that going to do to an already damaged brain.” P46

Concerns experienced during the pandemic extended beyond fears of becoming ill with COVID-19. When thinking about their social lives and connections, participants discussed their worry that socialization and social connections would be forever altered, and that isolation might continue even after the pandemic.

“Will there be, will some of the restrictions be internalized? So that people will be more hesitant to say, ‘Oh, sure, come on over’, type thing?” P45

Participants also expressed concerns that the pandemic was negatively impacting their health. Participants highlighted that not being able to see and connect with their families had caused them to feel “depressed” and noted that witnessing the negative impacts that the pandemic-related isolation had on others was “frightening”. Participants were concerned with the impact of isolation for themselves and others living with dementia. One participant expressed:

“When COVID hit, I said to them, this is going to be so hard on people living with dementia.” P46

This same participant expressed that watching their friends, who were also living with dementia, experience cognitive decline over the course of the pandemic was distressing, stating:

“I watched people go downhill so quickly. Because they weren’t being able to get out, they weren’t being able to connect with people. And I was watching people decline so quickly, and stuff like that, that it starts to affect me.” P46

The experience of social isolation caused by pandemic restrictions was discussed as having a detrimental effect on the cognitive abilities of persons living with dementia. Participants expressed sadness that their friends living with dementia experienced great “deterioration” in abilities as a result of being “cut off from everybody” because of the pandemic. For example, one participant discussed fellow members of their support group, stating:

“I know that some of those people from my group have become non-verbal and desperately lonely, and their cognition has decreased substantially.” P49

Participants were also concerned that the pandemic had resulted in changes to their routines, including activities that they used to do that challenged them, and that not participating in these routines and activities might have a negative impact on their abilities and independence in the future. For example, when discussing an activity often engaged in before the pandemic, one participant highlighted the ways in which travelling to a meeting allowed for mental engagement and stimulation. At the same time, the participant expressed concern that without this engagement, their cognitive abilities may be impacted, expressing:

“[Pre-pandemic] I’m socializing, and I’m paying attention at the meeting and being challenged in all these different ways. Whereas now, you know, I started the day down here in my office, and, and I don’t take a bus, don’t socialize in the same way. And that is a restriction that I find the hardest, because I think, once we are more able to go back to taking a bus and so on, I really do question how that will work for me. Whether I will have forgotten how to, to, you know, go through that whole process of taking the bus and figuring out the bus route and the times and, you know, the socialization aspect, you know, like, what have I lost? As far as capabilities are concerned.” P45

Worries about living alone during a pandemic were also of key concern for persons living with dementia, especially when thinking about the potential of contracting COVID-19 and requiring medical assistance.

“If I went into a full-fledged crisis, was I going to be able to manage to call for help? So, it really shone a light on that aspect of things for people living alone.” P50

Frustrations with life changes and restrictions

The subtheme Frustrations with life changes and restrictions was emphasized by many participants who described challenges brought on by the pandemic-related restrictions. Particularly, they expressed being upset that events, supports, and services were cancelled or no longer available. The frustrations expressed by participants could generally be categorized as frustration with the restrictions and the accompanying loss of independence experienced during the pandemic as well as frustrations with the general public for not always complying with the public health guidelines.

Difficulty accessing supports and services was reflected in a number of interviews. Participants even spoke to the experiences of others living with dementia who were not able to access support groups that had moved online during the pandemic.

“Now, unfortunately, a lot of people who would normally attend a dementia cafe, people my age and so forth, who unfortunately either do not have computers or do not know properly how to work them. So, a good number of the people who would normally be attending are no longer attending online because they simply don’t have the necessary components, shall we say, the necessary components to join in.” P47

When discussing how some supports and services have been transitioned to be online, one participant expressed:

“Yes, I am frustrated. I’m an in-person type individual. And doing over the phone or even over Zoom, whatever. It’s too impersonal.” P18

The impersonal nature of online communications was a source of frustration for many. One participant likened online social connections to a job, stating:

“Zoom is, it formalizes things, you know, like, ‘are you available now?’” P45

Another participant stated:

“Because if [my grandson would] call and say, I need help with my homework, I’d get in the car and go up. And now it’s all over Zoom.” P46

Life for many participants during the COVID-19 pandemic was often described as “just not the same” even with efforts to continue or improve social connections, supports, and services for persons living with dementia. The changes resulting from the pandemic were linked to both frustration and sadness, as one participant said:

“You know, that kind of social [interaction], but that’s all stopped - everything. Everything stopped with COVID.” P34

Participants grappled with feeling like a “burden” to loved ones and family given their need for increased support during this time, as well as their inability to support others in ways they used to. Participants also highlighted how the restrictions not only impacted their independence during the pandemic, but also limited whom they could go to for support. One participant said:

“So that’s hard. And now I have to ask my husband, ‘you mind if…’? But so … I feel like a burden if I ask, but I know we’re not, but I feel that way.” P33

“Well, just that friends would come by and take me, but now because we can’t get in the car with them unless they’re in our bubble. They can’t. So that’s hard.” P33

Social Connections and Isolation

The second theme that was identified was Social Connections and Isolation. Social connection was seen to be essential for maintaining cognitive functioning and mental well-being, and the experience of social isolation was especially detrimental to the cognitive abilities of persons living with dementia. Participants described a perception of either their own cognitive decline or the cognitive decline of others as a direct result of isolation, for example, stating “I felt a significant dip” when thinking about their own abilities, or “they regressed so bad” when discussing the situation of others.

Participants discussed missing authentic connections and experiencing a “lack of contact” with friends and family, as well as the ways in which social connections enhanced their day-to-day lives before the pandemic. Specifically, participants emphasized missing the “pace” of life and stressed that “socializing is super important in our lives”. For example, one participant stated:

“Well, my biggest thing I miss is giving hugs to people I love, that’s really been hard.” P33

Another highlighted how changes in family structure have been especially difficult:

“I think the [change in] family dynamics has been so upsetting to me, because I don’t get that hands on - get to see my kids. You know, don’t get to just pop in on them anymore, any of that stuff.” P46

Further, participants noted challenges with the restrictions associated with the pandemic, especially when thinking about social events that they would normally attend in non-pandemic times, such as weddings or funeral services for friends and family. One participant discussed their challenges with the restrictions in regard to experiencing the deaths of friends:

“The thing I think is the most challenging to me, I miss the most, I’m 71 years old, and I’m at the age of starting to lose a lot of my old friends. And we’re not allowed to go to funerals … and don’t really get to say goodbye, particularly. And that’s probably been the worst thing.” P48

When thinking about one’s own well-being, it was strongly emphasized by participants that experiencing social isolation had a negative impact on well-being. Participants expressed that persons living with dementia, especially, require stimulation to slow the “signs and symptoms of dementia”, stating:

“I got a feeling this isolation isn’t doing well for me.” P34

Unfortunately, social isolation is not a new experience for many persons living with dementia. Participants often expressed that they were “used to being isolated”, highlighting that many living with dementia “stay in an awful lot” even outside of the pandemic. One participant stated:

“I don’t mind self-isolation. Because of dementia, I’ve already experienced that.” P18

Another said:

“I’m not one to travel and not one to go away from home very often.” P51

Social connection was often linked to mental engagement and thought to have positive impacts on cognition for participants. For example, one participant highlighted that:

“I tell people that the reason I’m still able to do what I’m doing is because of the social interaction, that I’m still stimulating my brain, the best I can do.” P49

And others reflected on their experiences during the pandemic and what it meant to be able to stay connected to family and friends during this time, emphasizing:

“Connection is everything … I couldn’t imagine going through all of this without those connections, you know, those video calls and Zoom calls, and I couldn’t imagine being… that would keep me 100% isolated.” P50

Adapting to Change and Resilience through Engagement and Hope

The third overarching theme that was identified was Adapting to Change and Resilience through Engagement and Hope. During the COVID-19 pandemic, persons living with dementia have demonstrated their ability to adapt and overcome challenges. The resilience among the participants living with dementia was evident from discussions of their abilities to learn new ways of connecting with family and friends and overcoming challenges faced in trying to keep healthy during the pandemic.

Participants mentioned their ability to learn new ways of keeping connected with friends and family during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants discussed a “push” to learn new technologies to be able to keep in touch with family. One participant emphasized their capabilities despite their diagnosis, stating:

“I am more wired into technology than [my friends] are, even though I have dementia.” P34

In fact, many participants discussed a positive side to the pandemic as giving them more time to learn new things, accomplish goals, and get back to enjoying hobbies. Persons living with dementia also highlighted the benefits of having the time to “slow down” and enjoy a calmer pace of life. For example:

“And that’s something that I think is one of the good [things] that comes out of the pandemic is people have…they’re noticing things that they never noticed before, because they’re all too busy to notice them.” P50

“I think because we’re looking for joy, we’re actively looking for joy and happiness, I think we’re finding it. Whereas prior to COVID, I don’t think a lot of people are actually looking for those positives, at least acknowledging those positives like we are doing now.” P49

Participants also highlighted the importance of maintaining a sense of hope or focusing on a “light at the end” of the pandemic to help keep a positive perspective.

“Well, you just gotta stay positive. I think that’s one of the most important things.” P48

Keeping a positive attitude was helpful to some participants, but others used different coping strategies, such as distraction; for example, one participant said:

“I think the bottom line is I have done everything I can to divert my attention away from COVID.” P49

“If I can’t deal with it, well, I don’t know how you would deal with it. But I just put the negative stuff in the back of my filing cabinet. And try not to, to think of it or dwell on it. Just go about doing what I can do the very best that I can do it.” P49

Resilience was demonstrated in participants’ ability to adapt to the changing circumstances and participate in activities that supported well-being and helped manage stress. For example, participants discussed playing games, taking up activities such as cooking and photography, meditating, listening to music, exercising, volunteering, and taking on various projects. Many participants discussed how they have been trying to stay active, engaged, and busy. As one participant said:

“Yeah, yeah, just kind of holding my own, keep doing what I can do and get outside every day for a bit and that, so it’s just a matter of keeping moving really.” P51

Many participants who were interviewed were well-connected within the broader dementia community, and therefore highlighted the importance of these connections to their overall ability to maintain their well-being. Being “active” in the dementia community, or engaging as an advocate, was seen to protect against cognitive changes for many participants. One participant stated:

“If I were not an advocate, a very active advocate, I would have had great, great difficulty with this.” P49

We’re Not All the Same: Reflecting Individual Experiences of the Pandemic

Finally, the central theme of We’re Not All the Same: Reflecting Individual Experiences of the Pandemic was exemplified throughout the data. Participants’ experiences during the pandemic were unique to their own circumstances and abilities. At times these were seen as tensions in the data, where participants had different responses to similar experiences, including social connections, isolation, pandemic restrictions, the use of technology, and overall impacts of the pandemic on daily life. The perspectives of participants were unique to their circumstances. One participant articulated this idea clearly:

“The other thing I think we need to really focus on is that’s just me, that’s not every person living with dementia, because every person living with dementia has a different journey.” P46

The concept of tensions in the data was prevalent when considering social connections and the impact of the pandemic. Although in a previous theme, social connection and engaging in society was described as being important for cognition and to prevent the detrimental effects of social isolation, one participant had a different perspective, and discussed how the world becoming quieter had been a positive change for them. They said:

“So that quieter world has given me the ability to maneuver easier with my dementia. So that’s been really noticeable. Things like the grocery stores here, started an early morning hour for seniors, people with disabilities, and that has really been nice for me. There isn’t music blaring and there’s not all the banging and clanging that you normally find in grocery stores and all the busyness. And so, I can actually go to the grocery store, and manage getting my groceries with less difficulty.” P50

These differences in perspective, or tensions between ideas, serve as important reminders that each person’s experience with dementia and life during the pandemic is different. Whereas some enjoyed the quiet and peaceful atmosphere brought about by pandemic restrictions, others missed the freedom that they once enjoyed prior to the pandemic restrictions being put in place. For example, one participant reflected on the notion of freedom, highlighting the impact that pandemic restrictions have had:

“That’s the part that I missed the most. Not being free. Go jump in my truck and go wherever I want to go. You know, now, I gotta think, is it necessary or not?” P51

Another common expression heard in interviews was that connecting with family and friends online “is no substitute” for in-person connection. And although many participants demonstrated their resilience through learning new technologies and ways of connecting, this was often in tension with the idea that some forms of connection just can’t be replaced. For example, one participant said:

“So, it’s really, really difficult not to have those warm hugs. And that opportunity, just to, I mean it’s different talking to a loved one on a Zoom than it is one on one.” P49

Another participant touched on the tensions between the benefits and challenges of technology, especially around access to technology:

“I think [the pandemic] has reinforced the benefits of technology. But it also shows some of the challenges for people with dementia, their access to technology, and that relation to socialization.” P45

However, some participants had a different perspective on connecting with others during the pandemic using technology. One participant reflected on their increased use of technology to connect during the pandemic, highlighting how it has had a positive impact on friendships:

“Before COVID, months could go by and I wouldn’t hear from people. So, it’s not that same connection where you get to see them and give them a hug. But in some ways, it’s a whole new connection that is maybe even developing some of those relationships to be deeper.” P50

And some participants emphasized that not being able to connect in person with friends didn’t have a negative impact on their relationships, and in fact it allowed them to deepen their relationship with their family or their spouse, stating:

“And the other really positive, although, at the time, I didn’t think it was so positive. But my husband and I have kept up with the family traditions. So, we had a turkey dinner for the two of us with all the trimmings. And, and it seemed a bit. It was different. But it was, it was okay because we spent that time together. So, maybe because of COVID, our relationship may have strengthened, as opposed to, I hear a lot are having great difficulties. But I think ours is strengthened because we have to rely on each other for everything.” P49

“Yeah, I’d say a lot of good has come out of the negative. Like, our family, I mean, we were always close. But we’re even closer, now.” P33

“My husband and I are very close, always have been. But we’ve developed a new closeness during this, a different kind of closeness.” P46

Further, some participants highlighted that connecting with others online can be a positive, rather than a negative, experience and can allow for new opportunities to meet people and learn new things. For example, this participant enjoyed attending an online symposium:

“It was one of the most amazing experiences because there were people from all over the world. And I never would have been able to travel outside of my area, and to have them come in on my screen and talk to me about topics, talk to us about the things that are happening right now.” P49

And whereas many held a perspective that having to distance and be isolated was very challenging and frustrating, others expressed that even though there were fewer opportunities to go out or be engaged socially, there was always a “silver lining”. One participant highlighted this notion through discussing the benefits of not having to go out:

“And it’s still pouring with rain. So, I was lying there listening to it. And I thought, you know, the positive side of this pandemic, is actually not having to take the bus into town, not having to walk to a meeting and get soaking wet. So, you know, there’s always a bright spot.” P45

The experience and perspectives of isolation also varied across participants. Some participants anticipated that their experience as someone living with dementia and the isolation that can accompany that experience, would prepare them for the experience of isolation resulting from the pandemic. However, this perspective was also in tension with the experiences of others. As one participant described:

“Well, you know, people with dementia often isolate anyway, so we’re better equipped to weather the isolation storm. But let me tell you something, I was wrong, I was dead wrong.” P34

In contrast, other participants emphasized that their unique perspectives and experiences as a person living with dementia had prepared them to be resilient and maintain their well-being during the pandemic. For example, one participant highlighted the notion of choosing to “do things differently” and have a positive, rather than negative, perspective on the changes experienced during the pandemic, stating:

“I have people say to me, all the time, why are you so happy? And how are you managing through this, and it’s like, my life hasn’t changed that much. Except that the world has become a nicer place for me to maneuver through. And, yes, I’m isolated, I live on my own in my bubble of one. But I can get in my car and go for a drive with my dog. I can drive down, you know, a back road and stop and have a little picnic lunch and enjoy nature. I can go for a walk by myself. So even though people tend to say, well, we’re isolated, and we can’t do anything - you can still do things. You just have to decide to do things differently. And yeah, people with dementia have learned how to be adaptable and do things differently. So maybe for us, this is the silver lining, we’re getting through it easier than other people.” P50

Discussion

This study makes an important contribution to the literature, as it provides an in-depth understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the well-being of persons with dementia living in the community – as reported directly by these individuals. This study enhances our understanding of the experiences of persons living with dementia and contributes to the very limited evidence base that currently exists.

Findings from this study reinforce the individualized nature of dementia. Despite the common experience of COVID-19, the persons living with dementia who participated in this study described variability in their experiences, responses to the pandemic, and the corresponding impacts on their well-being. It was clear, however, that the public health measures implemented in response to COVID-19 as well as the adaptations that some organizations made to their services during the pandemic did not consider the heterogeneity of the population of persons living with dementia. Blanket sets of restrictions were put in place at provincial and/or local levels, such as stay-at-home orders, without consideration of the individual needs among persons living with dementia. In addition, some organizations decided not to move support services online for persons living with dementia, even though similar services were made available for family care partners. Although the rationale for these decisions is not fully understood, it may be that assumptions were made about the ability of persons living with dementia to use technology to participate in online services. Such assumptions fail to reflect our understanding of the individualized nature of dementia, including the variability that exists in skills and abilities. Indeed, our study has shown that many persons with dementia are comfortable with technology, and some persons with dementia have even assisted those without dementia to utilize technology.

The different responses to providing services (or not) for persons with dementia and care partners also suggests that stigma played a role in these decisions. It is well known that persons living with dementia experience stigma from the public (Blay & Toledo Pisa Peluso, Reference Blay and Toledo Pisa Peluso2010) and health care providers (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Kontos2013; Piver et al., Reference Piver, Nubukpo, Faure, Dumoitier, Couratier and Clément2013). Stigma can serve as a barrier to accessing care and support services for persons with dementia (Blay & Toledo Pisa Peluso, Reference Blay and Toledo Pisa Peluso2010; Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova, & Liu, Reference Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova and Liu2015; Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova, Liu, Riley, et al., Reference Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova, Liu, Riley and Einhorn2015; Piver et al., Reference Piver, Nubukpo, Faure, Dumoitier, Couratier and Clément2013). Therefore, not adapting services during the pandemic to make them accessible to persons with dementia could have long-term impacts, as these individuals may be reluctant to reach out for support after the pandemic is over because of the stigma that they experienced.

Concerns, fears, worries, and anxiety were a common theme identified through the interviews with persons living with dementia. Participants often expressed concerns for their own health and well-being, as well as the health and well-being of others living with dementia, especially surrounding the experience of isolation. Participants were often keenly aware of the negative impacts of COVID-19 on well-being as a result of isolation and lack of access to supports, and many expressed concerns for individuals who were newly diagnosed during the pandemic, or for persons living alone without the support of a spouse or family. Portacolone et al. (Reference Portacolone, Chodos, Halpern, Covinsky, Keiser and Fung2021) report that for persons with cognitive impairment living alone during the COVID-19 pandemic, distress from feeling extremely isolated was commonly experienced. The protracted experience of living with the pandemic’s public health measures begs the question about the long-term impact of isolation on the well-being of persons with dementia in the community. We have seen from this study that public health measures have impacted the ability of persons with dementia to engage in healthy behaviours (e.g., exercise, social connection) and has significantly impacted the mental health of some persons with dementia. In thinking about the needs of persons with dementia moving forward, it is likely that even more supports will be needed than would have been the case if there had not been a pandemic. Fewer opportunities to engage in exercise and being confined to one’s home may hasten muscle atrophy and contribute to physical decline (Lee, Tung, Liu, & Chen, Reference Lee, Tung, Liu and Chen2018), leading to increased support needs for activities of daily living. There may also be increased needs for mental health supports given the isolation experienced as well as the fear some have felt about going out into the public and contracting COVID-19. Depression can exacerbate cognitive decline, although these excess deficits can be addressed if treatment is provided (Ganguli, Reference Ganguli2009). Given the variability in experiences and responses to the pandemic, the needs of persons with dementia will require assessment, with services and supports tailored to individual needs. Governments must prepare for these individualized service needs in their post-pandemic planning.

Frustration was another common experience in the interviews. Not only frustrations related to the inability to see friends and family and to be active in the community, but also frustrations with individuals who were not adhering to the recommended public health measures. Other research that has examined the impact of COVID-19 on persons living with dementia has not identified frustration as an impact of the pandemic. This difference may be a result of the timing of data collection. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined the impacts of COVID-19 on persons with dementia after living with the pandemic for 6 months or more. Some research has investigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the broader population of older adults, concluding that restrictions, concerns for others, and isolation were all common stressors (Whitehead & Torossian, Reference Whitehead and Torossian2021). Studies that have examined the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on persons living with dementia have focused on the first 1–3 months of the pandemic (e.g., Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley and Gaughan2020, Reference Giebel, Lord, Cooper, Shenton, Cannon and Pulford2021; Roach et al., Reference Roach, Zwiers, Cox, Fischer, Charlton and Josephson2021). This is important given the roller coaster ride that all people, including persons living with dementia, have been on since the start of the pandemic, having to cope with: increases and decreases in the numbers of COVID-19 cases as well as new variants of the virus; public health measures, emergency orders, and re-openings and shut downs of services and supports; uncertainty and conflicting messages about the pandemic; the devastating stories of the impact of the pandemic, especially in vulnerable populations; and the hope of vaccines. The initial responses after the declaration of the pandemic are important to understand, but they may be different than those experienced later in the pandemic, given the fatigue and ongoing uncertainty after living with the pandemic for a longer period of time.

The importance of social connection and the experiences of isolation during the pandemic were discussed by all the individuals who participated in the study. Although technology was often identified as helpful, it was also clear that using it was not the same as having in-person and physical contact. The feelings of isolation were strongly tied to cognitive abilities and well-being by numerous participants, with many concerned with the detrimental effect that isolation might have on their cognition. This notion is supported in the broader literature as well, as loneliness and living alone are associated with greater cognitive difficulty (Poey, Burr, & Roberts, Reference Poey, Burr and Roberts2017). The loss of social connections and experiences of isolation were also identified in other research examining the impacts of COVID-19 on persons with dementia (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley and Gaughan2020; Roach et al., Reference Roach, Zwiers, Cox, Fischer, Charlton and Josephson2021). However, in these studies it was sometimes care partners speaking to these issues (e.g., impacts on cognitive function); the perspectives of persons with dementia were not always known.

Despite the concerns and frustration, persons living with dementia also highlighted their adaptive capabilities and resilience during these interviews, emphasizing their ability to adapt to challenges and maintain a positive outlook even when faced with isolation and other challenges. This adds further evidence that when provided with appropriate supports and tools, persons living with dementia can and should be included as active participants in society and in choices that shape their lives. In the study by Giebel et al. (Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley and Gaughan2020), the ability of persons living with dementia to adapt to the changes associated with COVID-19 was also highlighted. Persons with dementia in that study discussed their acceptance of the circumstances caused by the pandemic and their need to adapt. Like the current study, some participants in the Giebel et al. (Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley and Gaughan2020) study identified their comfort with technology as something that helped them to cope with the isolation, and also described their engagement with meaningful activities such as puzzles and gardening as ways to support their well-being. We know that persons living with dementia are resilient individuals who are able to develop creative strategies for adapting to day-to-day life (Bekhet & Avery, Reference Bekhet and Avery2018; Bellass et al., Reference Bellass, Balmer, May, Keady, Buse and Capstick2019; Williamson & Paslawski, Reference Williamson and Paslawski2016). Clark, Tamplin, and Baker (Reference Clark, Tamplin and Baker2018) have also described the desire of persons with dementia to “normalize” their lives. This has been discussed in the context of adjusting to their diagnosis and to the many transitions that they experience as their dementia changes. Adjusting to life during the pandemic highlights another layer of resilience exemplified by persons living with dementia.

To date, few studies have directly engaged persons living with dementia to understand their experience during the pandemic. Unfortunately, this is not unique to COVID-19. The voices of persons living with dementia are often excluded from research, with care partners and health care professionals often being asked to replace their voices (Alsawy, Mansell, McEvoy, & Tai, Reference Alsawy, Mansell, McEvoy and Tai2017; Dewing, Reference Dewing2008; Hellström, Nolan, Nordenfelt, & Lundh, Reference Hellström, Nolan, Nordenfelt and Lundh2007; Murphy, Jordan, Hunter, Cooney, & Casey, Reference Murphy, Jordan, Hunter, Cooney and Casey2015). As this research demonstrates, many persons living with dementia are able to share in-depth, nuanced depictions of their experiences and the impact of these experiences on their health and well-being. By hearing directly from persons living with dementia, the current study advances our understanding of the various ways that COVID-19 has impacted their well-being and their ability to understand the impact of the pandemic on their lives. Moving forward, it will be important to include the voices of persons living with dementia in authentic partnership (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Gillies, Carson, Whyte, Genoe and Loiselle2012) when developing and tailoring supports aimed at enhancing the well-being of persons with dementia, including supports that target physical well-being (e.g., exercise and physical activity programs), emotional well-being (e.g., art, dance, music, and other leisure activities), and social well-being (e.g., technological and non-technological approaches to connecting with others, peer-led social programs, dementia cafes).

The joint statement by the Canadian Association on Gerontology/L’Association canadienne de gérontologie (CAG/ACG) and the Canadian Journal on Aging/LaRevue canadienne du vieillissement (CJA/RCV) highlighted the need for interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the well-being of older adults (Meisner et al., Reference Meisner, Boscart, Gaudreau, Stolee, Ebert and Heyer2020). The joint statement also underscores the importance of hearing directly from older adults, including persons living with dementia, in understanding their experiences living during the pandemic. The current study has been able to successfully achieve both of these aims.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of the study included directly engaging persons living with dementia, which ensured that their voices and experiences were represented in the research. A limitation was the relatively small number of participants. We were also not able to reach persons living with dementia from diverse backgrounds, including those in racialized communities. This may be because of the profound stigma associated with dementia, and future research should work to capture the experiences of persons living with dementia from a variety of cultures and ethnicities, including those in racialized communities. Recruitment was challenging and likely influenced by COVID-19. Recruitment often involves working with organizations to share information about research opportunities. With reductions in services and the move to online activities, it was more difficult to identify individuals who may be interested in participating. It was also more challenging to reach individuals who did not have access to computers and social media. Nearly half of participants (4) participated by phone, and the remaining participants participated through an online platform (6). However, the small sample size was offset by the richness of the interviews. Participants spoke in detail about their experiences during the pandemic and how these experiences impacted their lives and well-being in varied and complex ways.

Although the goal of qualitative research is not to generalize findings, this study describes the perceptions of a relatively small group of persons living with dementia and does not include individuals at more advanced stages of the disease. Persons living with dementia in later stages or with additional challenges with activities of daily living may require a significant number of supports and services to support their health and well-being. For persons with moderate to severe dementia living in the community, the negative impacts of social isolation and lack of community services and supports may be much greater, as there have been very significant restrictions on day programs and respite. The study findings may reflect the experiences of persons living with earlier stages of dementia and not necessarily those with more advanced stages of dementia, for whom dependence on external community supports and services may be greater. Participants in this study had been living with dementia for an average of 9 years and tended to have a relatively high level of functioning. In fact, the majority of participants are individuals involved in dementia advocacy efforts, meaning that they are quite active. Therefore, the perceptions of the participants in this study may not be indicative of those of other persons with dementia across Canada. Future research should aim to understand the perceptions of COVID-19’s impact on a broader group of persons living with dementia, including the longer-term impact of the pandemic on their well-being and quality of life.

Conclusion

This study provides an in-depth understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of persons living with dementia in the community. It highlights the worries, fears, and frustrations of persons living with dementia during the pandemic and their perceptions of the future. This study describes the significant impact of isolation resulting from the public health measures and underscores the importance of being socially connected. Further, it demonstrates the ability of persons living with dementia to adapt and be resilient in the face of challenges posed by COVID-19. Importantly, the study highlights the fact that persons living with dementia are unique and that their responses to COVID-19 are also unique. Therefore, interventions to support persons living with dementia must be tailored to the needs, abilities, and circumstances of each individual. This is one of the first studies to hear directly from persons living with dementia about their experiences and perceptions of how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted their well-being. Further, it is the first study that we know of to do so with persons with dementia who have experienced the COVID-19 pandemic for at least 6 months. As such, it addresses important gaps in our understanding of the impacts of COVID-19 on persons living with dementia.

Funding Statement

Funding for this study was provided by the Network for Aging Research, University of Waterloo: COVID-19 and Aging Grants 2020. We extend our sincere thanks to the persons living with dementia who participated in this study. We are also grateful to the partner organizations who support this research and to Matea Zuljevic and Saara Jena Mohamed for their assistance with data collection activities.