Introduction

Canada’s population is aging, bringing many challenges and repositioning many practitioners from across the health care spectrum to focus on supporting older persons (Statistics Canada, 2016). For those who are experiencing chronic conditions or end-of-life issues, the focus shifts to palliative and other end-of-life care services including medical assistance in dying (MAID) practices (Truog et al., Reference Truog, Cist, Brackett, Burns, Curley and Danis2001). MAID may include either self-administration or practitioner-administration of drugs deliberately intended to end life. MAID practices are consistent with a patient-centred approach and allow patients to exercise autonomy in end-of-life decision making.

Literature shows that the offering of MAID practices allows some patients to feel a greater sense of control and autonomy over their personal outcomes (Dying with Dignity Canada, 2016; Karsoho Fishman, Wright, & Macdonald, 2016; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Chochinov, McPherson, Skirko, Allard and Chary2007). Moreover, allowing MAID to be provided at home can further help these individuals to feel comfortable and in control (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Chochinov, McPherson, Skirko, Allard and Chary2007). Although provision of service within a health care environment allows for stricter institutional control, the sense of personal control and comfort in a home environment may reinforce patient dignity (Li et al., Reference Li, Watt, Escaf, Gardam, Heesters and O’Leary2017).

Assisted death has been a long-standing issue of debate among policy makers, practitioners and Canadians. An overall shift in health care to patient-centred care and the recognition of patient autonomy as a pre-eminent value has fueled the conversation and created the impetus for legalization of MAID practices. This led the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC), on February 6, 2015, to unanimously rule in favour of legalization of MAID practices (Supreme Court of Canada, 2015). The court left it to the federal government as to whether or not formal changes to the Criminal Code of Canada would be legislated, but gave the government a year to do so.

Canada is one of more than 20 governments that have legalized MAID practices (Tretyakov & Cohen, Reference Tretyakov and Cohen2016). Canada joins other European countries including The Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany as well as a number of American states and the District of Columbia in this decision (Li et al., Reference Li, Watt, Escaf, Gardam, Heesters and O’Leary2017). The Netherlands, Belgium, and Oregon have been active leaders in this area internationally.

The legalization of MAID in Canada came with significant ambiguity for health care administrators, clinicians, and regulatory bodies. While requests for MAID were being received, there was limited guidance to implement, fund, and monitor those requests and services. Health care authorities were attempting to respect patient autonomy and dignity while at the same time ensuring the right to conscientious objection for health care providers (Canadian Medical Association, 2017). Conscientious objection to MAID is the option for a practitioner to refuse to become involved in delivering MAID services to patients (Landry, Foreman, & Kekewich, Reference Landry, Foreman and Kekewich2015). Although surveys suggest that a majority of medical practitioners and hospitals do not object to MAID, some are in disagreement or discomfited with the MAID practice (Braverman, Marcus, Wakim, Mercurio, & Kopf, Reference Braverman, Marcus, Wakim, Mercurio and Kopf2017). Alberta Health found similar sentiments in their extensive consultations with physicians and the public (Alberta Health, 2016).

This article presents the key highlights and features of the Alberta MAID framework. Alberta was one of the first few provinces to develop a comprehensive MAID framework following the 2015 Supreme Court ruling and the author (J.L.S.) received Canadian Medical Association Dr. William Marsden Award in Medical Ethics for establishing MAID in Alberta (Global News, 2017). Our focus is to highlight what Alberta has done differently to achieve one of the most successful MAID programs in Canada.

Approach

Alberta Health Services (AHS) delivers health services to more than 4,000,000 people living in Alberta and to some areas in British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and Saskatchewan (Silvius, Reference Silvius2017). The development and implementation of the MAID framework was an extensive undertaking including key stakeholder consultations, review of the literature, development of resources, and the implementation of the process. Over a very short period, a core group of practitioners created a single province-wide framework and process for patient assessment and provision of the service to ensure equitable access and consistent care across the province, both within AHS and in the community. The core group consulted with Alberta Health, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta, individual physicians, the Alberta College of Pharmacists, the College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta, and other health professional colleges for implementation.

The Alberta MAID framework developed includes a comprehensive policy, a comprehensive clinical guide with five distinct phases, and the Care Coordination Service (CCS). The guide identifies that individuals will pass in a non-linear fashion through these phases as they contemplate, determine actions, and make decisions to access these services. The MAID framework also includes a structured care pathway; a visual guide (placemat); and educational resources for professional staff, patients, and families to guide communication and process for practitioners and patients involved in MAID. In addition, AHS developed specific education for practitioners involved in MAID services including the MAID online modules, and dedicated significant resources to the development of a MAID Web site.

Literature Search Strategy

Our search strategy was adapted from a comparative policy analysis protocol as suggested by Mallinson, Misfeldt, Boakye, Suter, & Wong (Reference Mallinson, Misfeldt, Boakye, Suter and Wong2017). Our goal was to identify pertinent literature and reports that describe the development of MAID across Alberta and MAID services as implemented across Canada.

Health care across Canada is the responsibility of the provincial and territorial governments and varies significantly across the country. With these significant differences in structure and resources, we expected to find a variety of materials as potentially relevant documents including articles, presentations, and sections from relevant policy documents, opinion papers, and official guidelines or standards of practice. PubMed and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases were searched for articles from January 2007 to January 2018. We supplemented the electronic search with extensive grey literature searches, conference abstracts from ethics and health system conferences, technical reports of MAID protocols, and institutional policies for MAID.

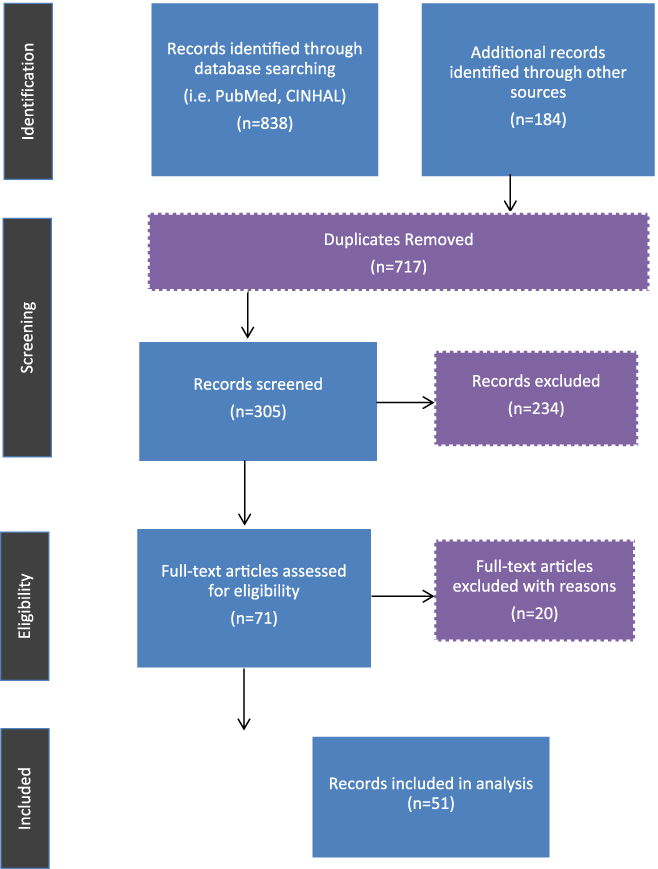

For grey literature, we used snowball sampling (such as pursuing references of references) to locate potentially relevant materials on MAID services in Canada. We reviewed key articles and dispersed the searches across Web sites, including the Health Council of Canada, Canadian Mental Health Association, the Government of Canada, and the Canadian Medical Association. We searched earlier reports and grey literature for information about MAID frameworks or standards of practice offered in each province and territory. We included literature, articles, and reports that describe the provision of MAID by either assisted suicide or voluntary euthanasia for adults over 18 years of age. We included technical reports, institutional policies, clinical practice guidelines, and clinical studies (case reports, observational studies or quantitative/qualitative studies). We excluded reports describing other end-of-life practices, including withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining treatment, palliative sedation, or unintentional hastening of death via medications for symptom management. We did not include opinion papers, newspaper articles, or blog posts. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram shows the results of our literature search (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram showing literature search for medical assistance in dying

Alberta MAID database

Alberta receives a number of patient inquiries for MAID, which are recorded in a database. The purpose of the database is to record all inquiries and requests related to MAID along with demographic information of patients.

Data Analysis

The quantitative data collected from MAID database were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. All analyses excluded missing data. We used the t-test and χ2 test analysis to determine if there were significant differences; Mann–Whitney U test was used for skewed data. SPSS version 19 was used for statistical analysis; p value < .05 was considered as significant.

The literature synthesis was mainly focused on extracting information related to existing MAID policies, including any commonalities and differences, and any general conclusions regarding the development and implementation of MAID frameworks. A variety of resources was considered in the review and documented using data extraction matrices. These extractions included information about the source (e.g., author’s name, article title, publication year, main purpose, target audience, type of source, variables or key indicators, results/main themes, and any conclusions or recommendations). We did not intend to cover the entire record of MAID literature and practices in detail.

Results

Key Features of the AHS MAID Program

A key feature of Alberta’s response to the new legislation was creating a single point of contact for patients, families, and health care providers through the MAID CCS (Table 1). Alberta was the first jurisdiction to create this service; others have, or are looking at, a similar model. This unique coordinating body is available to support patients, families, and care teams through the process of MAID, and serves as the central resource for consultants, transfers, forms, information, colleagues, and pharmacists. The CCS is accessible to all Albertans without referral. This approach supports patient-centred thinking, which increases access for the patient and ensures that the patient is well cared for while balancing the rights and values of a practitioner who may not be willing to participate.

Table 1: Key features of the Alberta MAID policy/program

Note. MAID = medical assistance in dying.

A comprehensive education program and resources about end-of life care and communication are also available through the MAID program for professional development. Medical practitioners play a key role in alleviating the anxiety patients and family members may have about the MAID process. Recognition of communication and teamwork skills in this area can better prepare medical practitioners when delivering MAID; including knowing how to support and counsel patients and families, sensitivity in communication, and ensuring respect for a variety of religious and cultural beliefs. Research from the United States suggests that a “structured bereavement program” for clinicians may be an additional resource for clinicians and families to reflect on their experiences about the quality of care, successes, and challenges (Truog et al., Reference Truog, Cist, Brackett, Burns, Curley and Danis2001).

MAID Service Delivery

In compliance with federal legislation, Alberta requires that at least two physicians or nurse practitioners skilled in assessing patients’ prognosis, suffering, and capacity complete independent assessments. By design, these assessments are kept entirely separate. Specific forms are available to help guide the components of the assessments. Both assessors must agree on the conclusions of their assessments to either provide or decline MAID. Disagreements between the two assessors are resolved through subsequent discussion, and experience has shown that decisions may go either way. Capacity to provide informed consent is assessed at defined points in time to ensure that the patient is willingly agreeing to seek MAID, including at the time of signing the request form, the assessments, and immediately prior to MAID delivery.

As part of a patient-centred care approach, the implementation of MAID services in Alberta is culturally sensitive. Patients are given every opportunity to experience spiritual meaning and fulfillment including the involvement of clergy and end-of-life rites at the bedside. Additionally, Alberta offers the opportunity to complete MAID in the patient’s home. Research shows that environment can play an important role in promoting the patient’s comfort at end-of-life (Georges et al., Reference Georges, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Muller, Van der Wal, Van der Heide and Van der Maas2007), suggesting that returning to a more familiar (and possibly more private) setting is ideal. This transfer may also support less technology use and cost.

It is interesting to consider other safeguards not included in the Alberta MAID framework. For example, in British Columbia, one out of two MAID assessments may be completed by telehealth technology; however, another “regulated health professional” must be in attendance with the patient to bear witness to the assessment (College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia, 2016).

Data Reporting and Monitoring

Data monitoring and reporting is of critical importance in documenting the successes and challenges of the MAID program in Alberta. The CCS maintains a MAID database as part of data monitoring and quality assurance. Reports generated from the database are provided for quality assurance and monitoring purposes. Ontario, Quebec, and Manitoba have developed their own distinct data management programs for this purpose.

Findings from Alberta MAID database

Table 2 provides a description of MAID requests and inquiries from July 2017 to April 2018. Of the 555 inquiries, 306 inquiries were requests for MAID and 231 were inquiries for information only. Eighteen inquiries had missing data; the nature of their request was unclear. The median age for those who made MAID requests was 70 with 55.3 per cent of persons being male. A large proportion of patients had a diagnosis of cancer. The primary diagnosis types included cancer (70%), neurodegenerative disease (10.4%), cardiovascular disease (4.3%), respiratory disease (6.0%), and other disorders (9.7%). Other diagnoses included paranoid schizophrenic disorder, and severe pain.

Table 2: Alberta MAID metrics for MAID inquiries (July 1, 2017–April 4, 2018)

Note. a The rural–urban classifications used in this article are based on the Alberta Health Services (AHS) /Alberta Health (AH) Official Standard Geographies as produced by Geographic Area Working Group (GWG). The GWG was a pan-provincial group that included representation from multiple AHS portfolios as well as AH. These individuals established principles, guidelines, and standards as well as adopting standard methodologies and evidence-based approaches to construct all geographic areas in 2010. These rural–urban continuum areas are up to date as of January 2018. MAID = medical assistance in dying.

Out of these requests, 174 were approved and a scheduled procedure date was provided. Seventeen of these requests were not completed for reasons including withdrawal of request, death prior to procedure date, loss of capacity, or other reasons. Overall, 28.2 per cent (157 of 555) of the individuals who inquired about MAID received the service. All MAID deaths were clinician- administered deaths. The median age was significantly higher for those whose request for MAID was approved compared with those that were unapproved (Table 3). MAID requests by females were 1.5 times more likely to be approved than requests by males. No significant differences were seen in approval rates between urban and rural areas. Although we cannot determine causal relationships with this small data set, this suggests an interesting trend in how MAID services have been accessed and utilized.

Table 3: Comparing the characteristics of patients who requested MAID (July 1, 2017 – April 4, 2018)

Note.* Z score, based on Mann–Whitney U test. p values were calculated using 95% confidence level. MAID = medical assistance in dying, CI = confidence interval, LTC = long-term care.

Cross-jurisdictional comparisons

Tables 4 and 5 show our findings from the comparative policy analysis of MAID practices in Canada. From this search, we developed a policy matrix with the key features and gaps in policies across Canada. Each province has developed a distinct resource model for service delivery for MAID, with a few provinces dedicating specific resources for the service as a central point of contact whereas others incorporate these practices as part of existing practitioner workloads. The tables also reflect potential gaps where specific provinces may need to develop their own resources and policies for improved implementation. Another clear distinction is the availability of the patient care pathway. Alberta, Ontario, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island have some form of patient care pathway widely accessible; however, none is as directive and specific as that of Alberta. This resource may help mitigate any anxieties in the process for patients and families as they consider MAID as part of end-of-life services.

Table 4: Characteristics of MAID services across Canada

Note. MAID = medical assistance in dying, BC = British Columbia, AB = Alberta, SK = Saskatchewan, MB = Manitoba, QC = Quebec, ON = Ontario, NS = Nova Scotia, NB = New Brunswick, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador, PE = Prince Edward Island, YT = Yukon, NT = Northwest Territories, NU = Nunavut.

Table 5: Policy comparison of medical assistance in dying (MAID) services across Canada

Note. MP = medical practitioner, SW = social worker, PO = physician only, BC = British Columbia, AB = Alberta, SK = Saskatchewan, MB = Manitoba, QC = Quebec, ON = Ontario, NS = Nova Scotia, NB = New Brunswick, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador, PE = Prince Edward Island, YT = Yukon, NT = Northwest Territories, NU = Nunavut, SCC = Supreme Court of Canada.

Our analysis suggests that differences lie in the development, key features, and monitoring of outcomes of the individual MAID policies or programs. These differences, we believe, are based on factors of environment and context, identified performance indicators, population values, interests, and resources available in each region.

Discussion

Over the past two years, MAID programs across Canada have been developed and implemented in varying fashion. The Canadian legislation to legalize MAID services and expert advisory communities of practice have generally informed the processes for each province. However, in spite of the work by the Provincial-Territorial Expert Advisory Group on Physician-Assisted Dying (2015), there are no common definitive strategies related to the implementation of MAID. The consistent themes that we found across MAID programs in different regions include: (1) protection of rights of vulnerable patients, (2) recommendation for family involvement, (3) right to confidentiality, (4) privacy of information, (5) recognition of conscientious objection, (6) right to practice rituals and cultural beliefs, and (7) need for sensitive and compassionate communication among medical practitioners, patients, and families. However, there are a number of key differences in implementation of MAID programs across Canada.

Our findings emphasize the importance of stakeholder engagement and consultation for a clearly defined policy and implementation for MAID. In Alberta, the intent was to develop one system for all of Alberta, whether within AHS or outside of AHS facilities and programs. The collaborative development with external partners of a written MAID policy framework, detailed guideline, and care pathway was key to supporting the consistent implementation across a large population base; these documents provide directive and detailed guidance to medical practitioners involved in MAID. Overall, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec have provided comprehensive process pathways and monitoring measures to implement MAID services. Other provinces such as Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, and British Columbia have indicated that their comprehensive policies are in the works and refer to standards developed either by their colleges of physicians and surgeons or by AHS. A policy framework acts as a check and balance to provide a consistent and appropriate delivery of MAID. Education about the framework and its dissemination also support the consistent and accurate delivery of services.

The primary stakeholders and players involved in developing the MAID frameworks differed according to the region. For example, in Alberta, AHS, the central health authority, was a key player in the development of the MAID policy, whereas in Saskatchewan, the College of Physicians and Surgeons was the primary player. Ontario commissioned a consulting group to develop an aggregated policy and framework that can be applied across all public health regions in Ontario. Although these differences are contextual, we found (according to the Alberta experience) that where provincial institutions or health authorities play a central role in all stages of the development process, they can support strong mechanisms, including financing, that strengthen consistency and coordination.

Limitations

A few limitations need to be considered when interpreting findings from this article. First, we reported those individuals who received MAID services and received a procedure date; however, some individuals dropped out of the program because of early death or for other reasons. Second, although we used a systematic approach to consider the various features of MAID policies in Canada, comparisons are difficult because of the differences among provincial health care structures and the populations served by each health authority.

Conclusions and Recommendations

A range of policies and frameworks are currently in use to support and guide the implementation of the MAID legislation across Canada. It is clear that although legislation serves as the supporting backdrop for most policies, the implementation of these policies and strategies differs significantly across Canada.

The AHS MAID framework was established as a province-wide policy, as well as guidelines and processes to deliver MAID services equitably and effectively across the province of Alberta. The development of the Alberta MAID program was resource intensive; its sustainability and maintenance largely involves utilizing resources of the existing health care system in Alberta.

The following recommendations are based on the comparison of approaches and policies of MAID:

Development of a MAID Framework

• Engage stakeholders (e.g., health care providers, policy makers, patients, and family members) and appropriate regulatory bodies in the development of a consistent MAID framework.

• Assign a dedicated team of professionals to act as the first point of contact for those considering MAID as part of their end-of-life care.

• Consider cultural aspects in the development and implementation of MAID services.

Implementation and Uptake

• Provide clinical teams with effective dissemination and feedback loops to encourage knowledge transfer and uptake.

• Provide learning resources and capacity-building opportunities for health care provider such as webinars or online modules.

• Incorporate standards and expectations that support patient-centred care and practitioner support.

Reporting and Outcomes Review

• Establish safeguards related to MAID independent assessments.

• Identify key indicators for reporting and data collection requirements.

• Provide clear opportunities for bereavement and loss support for clinicians as well as opportunities for reflection on practice.