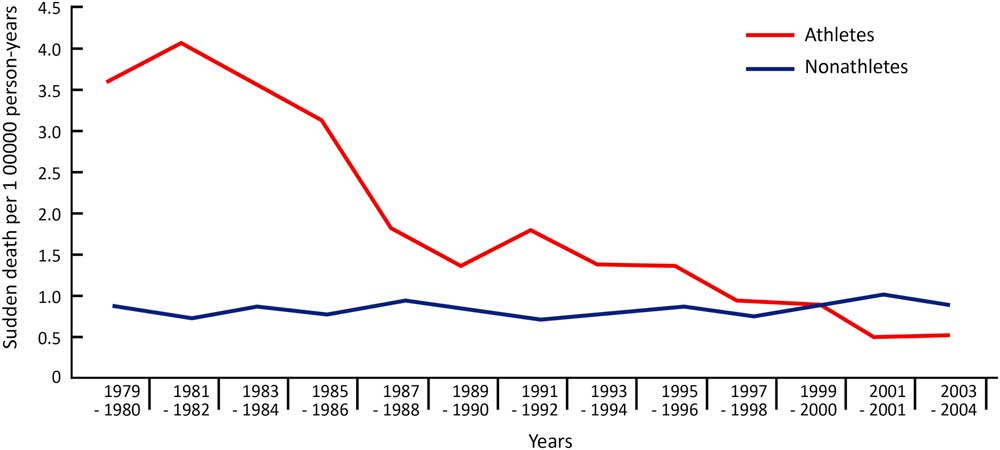

Sudden death in young athletes is a rare but dramatic event with an incidence <1–3/100,000 athletes.Reference Maron 1 – Reference Maron, Doerer and Haas 3 These deaths are mainly caused by cardiovascular diseases, with cardiomyopathies and coronary anomalies being the leading causesReference Corrado, Basso and Rizzoli 2 – Reference Corrado, Basso and Schiavon 4 (Fig 1). Corrado et al demonstrated that the early identification of cardiovascular diseases through a nationwide screening programme could prevent athletes from suffering sudden cardiac death. Screening could lead to a decrease of 89% in such deathsReference Corrado, Basso and Schiavon 6 (Fig 2). Screening programmes are recommended by several medical and sports associations, such as the European Society of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the International Olympic Committee, and the American Society for Sports Medicine.Reference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 , Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 – Reference Drezner, O’Connor and Harmon 9 No international paediatric society, however, appears to have made any recommendations in this regard. Although screening programmes are universally recommended, the protocols are not uniform: the difference in most programmes being the inclusion or not of 12-lead electrocardiogram screening. The major concerns against electrocardiogram screening are the additional costs and the number of false-positive results.Reference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 The implementation of electrocardiogram guidelines by Corrado et alReference Corrado, Pelliccia and Heidbuchl 10 and Drezner et alReference Drezner, Ackermann and Anderson 11 , and special training for the physicians involved, has led to a reduction in the number of false-positive results.Reference Drezner, Asif and Owens 12 Underlining the importance of a standardised screening programme by trained physicians, Thünenkötter et al performed pre-participation examinations in all athletes of the FIFA World Cup 2006, and demonstrated that 1% of these athletes, who play in the best leagues all over the world, had findings indicating the presence of cardiovascular diseases.Reference Thünenkötter, Schmied and Grimm 13

Figure 1 Cardiovascular reasons for sudden cardiac death in athletes (modified Maron et alReference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 ). ACM/ARVC=arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; HCM=hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy; MVP=mitral valve prolapse.

Figure 2 Annual incidences of sudden cardiac death in Italy among screened and unscreened athletes (modified Corrado et alReference Corrado, Basso and Schiavon 6 ).

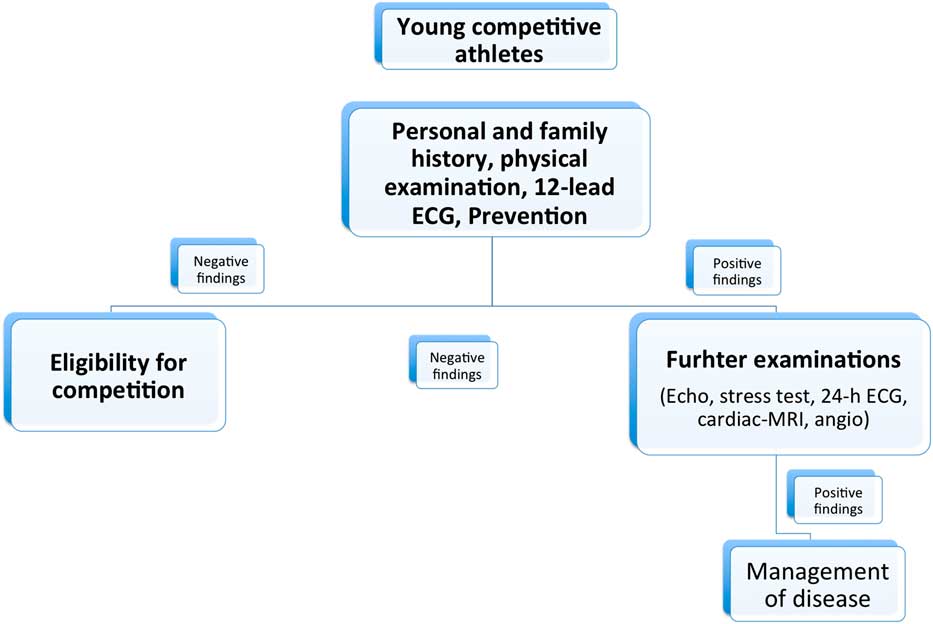

The Working Group for Preventive Cardiology of the Association of European Paediatric Cardiology decided to support the recommendation of the European Society of Cardiology,Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 with special focus on the necessity for a 12-lead electrocardiogram to facilitate the timely detection of cardiovascular abnormalities in young athletes. This could result in proper diagnosis and therapy after detection, and reduce the risk for sudden cardiac death. The study, moreover, wishes to emphasise the importance of proper patient education to prevent sudden cardiac death due to myocarditis (Fig 3).

Figure 3 New Association of European Paediatric Cardiology guidelines for pre-participation screening in young competitive athletes. ECG=electrocardiogram.

Causes of sudden cardiac death

Maron et alReference Maron, Doerer and Haas 3 investigated the sudden death of 1866 athletes in North America. Of this total, 56% of the deaths were due to cardiovascular diseases, 22% due to blunt trauma, 3% due to commotio cordis, and 10% due to miscellaneous causes. The leading cause of sudden cardiac death in this study was hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, as seen in 36% of the athletes, followed by coronary anomalies (17%), myocarditis (6%), and arrhythmogenic right-ventricular cardiomyopathy and mitral valve prolapse (4%) (Fig 1).

After the implementation of a nationwide screening programme in Italy, the leading cause of sudden cardiac death was arrhythmogenic right-ventricular cardiomyopathy, which was seen in 22% of those surveyed. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy as a cause of sudden cardiac death was found in 2% of the athletes, whereas the incidence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in non-athletes who were not screened was 9.5%. This discrepancy is explained by the unique exposure of Italian athletes to this systemic cardiovascular screening programme.Reference Corrado, Basso and Schiavon 4 , Reference Corrado, Basso and Schiavon 6 Table 1 shows the causes of sudden cardiac death after the implementation of the screening programme in screened athletes and unscreened non-athletes.

Table 1 Causes of sudden cardiac death in screened athletes and unscreened non-athletes in veneto region of Italy from 1979 to 1996 (modified Corrado et alReference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 ).

ACM/ARVC=arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; HCM=hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; MVP=mitral valve prolapse

It is very important to note that some diseases can show a negative history and absent symptoms on physical examination in children. In particular, progressive diseases such as arrhythmogenic right-ventricular cardiomyopathy, usually starting during late adolescence, and heterogeneous diseases such as mitral-valve prolapse, which can appear in mild-to-severe forms, often have no symptoms in children, emphasising the importance of follow-up examinations.Reference Marcus, McKenna and Sherrill 14 , Reference Avierinos, Gersh and Melton 15

It is not the purpose of this paper to discuss the necessity of screening the entire population aged 12–25 years for cardiovascular disease, as this might not be as effective as screening in young competitive athletes alone.Reference Maron, Friedman and Kligfield 16

Recommendations for a cardiovascular screening programme

Nearly all cardiological and sports associations recommend that a screening programme should include a family and personal history and a physical examination, but they continue to challenge the need for a routine 12-lead electrocardiogram.Reference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 , Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 , Reference Bille, Figueiras and Schamasch 8 The screening should be performed on athletes when they start their competitive activity, and should be repeated routinely every 1–3 years.Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 , Reference Drezner, O’Connor and Harmon 9 , Reference Marcus, McKenna and Sherrill 14 , Reference Avierinos, Gersh and Melton 15

A great number of conditions causing sudden cardiac death are genetically determined, indicating the importance of family history. According to the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology, athletes are considered to be at risk for sudden cardiac death when their close relatives had experienced a premature heart attack or a sudden cardiac death (<55 years of age in men, <65 years in women).Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 , Reference Maron, Friedman and Kligfield 16 The presence of a disabling cardiovascular disease, such as cardiomyopathy, Marfan Syndrome, long QT syndrome, Brugada Syndrome, severe arrhythmia, or coronary artery disease, is also indicative of being at risk. Personal history is considered positive in case of a family history of exertional chest pain, syncope or near-syncope, irregular heartbeat or palpitations, unexplained shortness of breath, or fatigue during exercise.Reference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 , Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 , Reference Maron, Friedman and Kligfield 16

Physical examination is considered positive if a heart murmur – any diastolic and systolic grade >2/6, mid- or end-systolic click, second single or widely split or fixed heart sound – is detected. A diminished or delayed femoral pulse, an irregular heart rhythm, or elevated blood pressure readings over the 95th percentile also indicate positive risk.Reference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 , Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 , Reference Maron, Friedman and Kligfield 16 , Reference Neuhauser, Thamm and Ellert 17 Other positive findings may be musculoskeletal or ocular abnormalities suggestive of Marfan Syndrome.Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 , Reference Maron, Friedman and Kligfield 16

The American Heart Association still recommends a screening programme that includes only personal and family history and physical examinations.Reference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 In contrast, the European Society of Cardiology, the International Olympic Committee, several European countries, and several professional sporting leagues recommend cardiovascular pre-participation screening including a 12-lead-electrogradiogram.Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Bjornstad 7 , Reference Bille, Figueiras and Schamasch 8 This procedure enhances the probability of detecting cardiovascular diseases in athletes.Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Heidbuchl 10 , Reference Drezner, Asif and Owens 12 , Reference Asif, Rao and Drezner 18 The most common concern regarding the electrocardiogram is the high incidence of a false-positive reading, which can result in further cardiovascular evaluation or restriction from sport.Reference Maron, Thompson and Ackerman 5 After the recommendation of interpretation criteria for a 12-lead electrocardiogram by Corrado et al, the proportion of abnormal electrocardiogram readings decreased from 16 to 9%.Reference Corrado, Pelliccia and Heidbuchl 10 , Reference Weiner 19 These criteria have recently been revised by an international committeeReference Drezner, Sharma and Baggish 20 (Table 2).

Table 2 Classification of ECG abnormalities in athletes (modified Drezner et al. Br J Sports Med 2017)

Electrocardiogram patterns in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are shown in up to 95% of the patients studied.Reference Maron, Roberts and Epstein 21 The nationwide screening programme in Italy that included a 12-lead electrocardiogram resulted in a significant reduction of sudden cardiac death, showing a 77% higher sensitivity for detecting hypertrophic cardiomyopathy than history or physical examination.Reference Corrado, Basso and Schiavon 6 Drezner et al showed an improvement in electrocardiogram interpretations by primary care and cardiology physicians from a baseline of 74/85%–91/96% after they used an electrocardiogram interpretation tool.Reference Drezner, Asif and Owens 12 Asif et al summarised in their reviews that the cost-effectiveness of a screening programme that includes an electrocardiogram cannot be doubtedReference Asif, Rao and Drezner 18 , Reference Asif and Drezner 22 (Table 3).

Table 3 Cost-effectiveness models for cardiovascular screening (modified Asif et alReference Asif, Rao and Drezner 18 ).

CE=cost-effectiveness; ECG=electrocardiogram; FP=false-positive; HCM=hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ICE=incremental cost-effectiveness; LQTS=long QT-syndrome; LY=life-year; QALY=quality-adjusted life-year; SCD=sudden cardiac death; WPW=Wolf–Parkinson–White

Pre-participation examination should be performed by doctors trained in examining athletes and in reading their electrocardiogram.

An important part of a screening programme is the importance of reducing the incidence of sudden cardiac death due to myocarditis: the risk for sudden cardiac death due to myocarditis is about 6–12%.Reference Maron, Doerer and Haas 3 , Reference Corrado, Basso and Schiavon 6 , Reference Levine, Klugman and Teach 23 It is important to note that the clinical presentation of myocarditis with an asymptomatic course up to sudden cardiac death complicates both diagnosis and prevention. Weber et al showed that, in myocarditis, the risk for sudden cardiac death does not correlate with the intensity of inflammation.Reference Weber, Ashworth and Risdon 24 In addition, exercise in patients suffering from myocarditis enhances the viral disease, worsens cardiomyopathy, and aggravates the autoimmune process against the heart tissue.Reference Kiel, Smith, Chason and Khatib 25 , Reference Hosenpud, Campbell and Niles 26

The best method of prevention would be a detailed education of young athletes during the pre-participation examination, explaining to them the need to pause exercise and competition during an infection to reduce the risk for sudden cardiac death. The education should also include spreading awareness about the need to recognise red flag symptoms and the importance of new family history.

Conclusion

This manuscript posits that these recommendations are the first by an international paediatric society. The cardiovascular pre-participation screening of young athletes should include personal and family history, physical examination, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram. Trained physicians using the Electrocardiogram Criteria should perform the screening programme. The screening programme should include instructing athletes to suspend exercise during infections and recognise red flag signs. The screening should be performed before the start of competitive sports and should be repeated every second year to detect progressive diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Nico Bloom, Laszlo Kornyei, Jörg Stein, and Andrea Jakab for reviewing the manuscript and for their valuable inputs.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial enterprise, or not-for-profit sector.

Conflicts of Interest

None.