On Saturday the “bowling club Lustige Neun,” of which we are already aware, organized a spring ball at the Concordia ballrooms in Berlin, Andreasstr. 64. The event, in which approximately 300 lesbians (Lesbierinnen) took part, started around 8 o'clock and ended around 1 o'clock. … There was no occasion to intervene. Apart from displays of affection, which were secretly exchanged here and there at the tables, and also while dancing, nothing special was noticed. During the breaks, the women largely stayed at the buffet and at the bar. Quite a bit was imbibed. Mostly beer, caraway schnapps, and prosecco, as other drinks were not available.Footnote 1

This description of a large, festive gathering of lesbian women was penned not in the famously raucous 1920s, but rather on April 22, 1940, seven months into World War II. A criminal police secretary observing the festivities took down these words, which today are catalogued in a large file dealing with the group Lustige Neun. This club, about which scholars have long known, provides something of a confounding window into the experiences of lesbian women in Nazi Germany.Footnote 2 It persisted for well over a decade, with roots in the Weimar era. Although the police had placed the club under surveillance by 1935, it continued to host large events until at least the spring of 1940. The file, in which detectives’ sometimes-amusing descriptions of the club's antics are preserved, paints a picture of guarded tolerance. Although police officers regularly showed up to the events, they typically, as in April 1940, found no reason to intervene, knowing that lesbianism was not punishable under German criminal law. At the same time, they jotted down information about the men at the events, Jewish women, and other perceived outsiders. As Jens Dobler has suggested, the endurance of Lustige Neun in the Nazi era indicates that “neither the criminal police nor the Gestapo opposed the gatherings with vigor. Paragraph 175 [of the penal code] exclusively punished male homosexuality; the investigative authorities were hardly interested in lesbians.”Footnote 3

But not all lesbian encounters with the Nazi police had such insouciant endings or imply such rosy conclusions about lesbian life in the Third Reich. Over the last several decades, historians have uncovered ever more cases of lesbians sent to prisons and concentration camps or even murdered. These strikingly different incidents point to an ongoing debate among scholars about the place of lesbians under German fascism, a debate that has both scholarly and political ramifications and that stretches back to early gay liberation efforts during the Cold War. “As gay men increasingly invoked the pink triangle in the face of the AIDS epidemic,” Erik Jensen has argued, “some lesbians began to seek their own memory of Nazi oppression.” These early historical efforts sought to show that female homosexuals too had suffered under the Nazis, with some writers contending that the black triangle used to identify so-called asocials had frequently marked lesbian concentration camp prisoners.Footnote 4

Although an ever-growing body of historical evidence has grounded this debate, disagreements remain.Footnote 5 Dobler, for example, contends in a recent chapter, “Just as gay men, lesbians too were a persecuted group.”Footnote 6 Although female homosexuality was never criminalized in Germany during the Nazi period (Austrian law did criminalize it and continued to even after Germany annexed the country in 1938), scholars have uncovered numerous cases of lesbians who fell into the sights of the judicial and bureaucratic apparatuses between 1933 and 1945. And as the Nazi persecution of gay men has become ever more publicized—in particular with the 2008 erection of a monument to the homosexual victims of the Holocaust in Berlin's Tiergarten—some activists and historians have insisted on the recognition of lesbian women as co-victims of Nazi terror.Footnote 7 The group Autonomous Feminist Women Lesbians from Germany and Austria has lobbied the female concentration camp Ravensbrück to lay a memorial orb with the inscription, “Lesbian women were considered ‘degenerate’ and were persecuted and murdered as ‘asocial,’ resistant, and crazy, and for other reasons.”Footnote 8

Yet, other scholars have objected vehemently to these efforts. Pointing to the fact that paragraph (§) 175 never criminalized female homosexuality, Alexander Zinn insists that “women were spared the surge of persecution (Verfolgungswelle) in contrast to homosexual men.”Footnote 9 Even while making a case for a more complex understanding of the term, I too have argued that some lesbian women were tolerated in the Nazi period.Footnote 10 Claudia Schoppmann, the most respected and prolific historian of lesbianism in the Third Reich, has taken different tacks in different publications, sometimes arguing that there was no comparable oppression, other times making a more aggressive case that lesbians were indeed persecuted.Footnote 11 At times, these disagreements even extend to how historians characterize individual cases. These disputes typically revolve around how to read the evidence and, in particular, the gaps in official records.Footnote 12 At the time of writing, no agreement has been reached regarding a memorial commemorating lesbians incarcerated at Ravensbrück.Footnote 13

Recent work has sought to move past these debates over persecution and tolerance. A number of scholars have criticized the debate's political dimensions, such as Anna Hájková, who mourns the “politicized competition of victim groups.”Footnote 14 So, too, Zinn suggests in a recent article that the “instrumentalization of history is in danger of placing emphasis on questionable points, disregarding undesirable aspects and thereby clearing a path for a new form of historical falsification.”Footnote 15 In a similar vein, Gudrun Hauer writes that this work cannot be about “a contest, a competition between different ‘victim’ groups, but rather about recognition.”Footnote 16

The most compelling model for how to get past the dispute over persecution has been Laurie Marhoefer's 2016 article about Ilse Totzke, a lesbian (or, as Marhoefer notes, possibly a so-called transvestite) who lived in Würzburg. In it, she proposes:

Historians need to consider the concept of risk. Though not the subjects of an official state persecution, gender-nonconforming women, transvestites, and women who drew negative attention because of their lesbianism ran a clear, pronounced risk of provoking anxiety in neighbors, acquaintances, and state officials, and that anxiety could, ultimately, inspire the kind of state violence that Totzke suffered.Footnote 17

Marhoefer's work points out that female homosexuality, even if not a distinct category of persecution, eased some women's paths to the concentration camps. Any outsider identity reduced one's social capital and put a target on their back. Schoppmann similarly suggests that lesbians faced “multiple persecution,” pointing to women, such as Jewish lesbians, who were stigmatized and oppressed for a variety of identities and behaviors.Footnote 18

In this article, I try to flesh out these suggestions and put them in dialogue with one another. Whereas most studies of lesbians in Nazi Germany since Claudia Schoppmann's groundbreaking work from the 1990s rely on a handful of case studies, I propose to combine close readings of three cases of lesbianism in the Third Reich with a broader analysis of twenty-seven other cases already known to scholars. To the best of my knowledge, historians have not yet published about two of these cases, those of Ruth H. and Waltraud Hock. The third case study, that of Käthe Abels, I have adapted from a recent chapter in a German-language edited volume.Footnote 19 By combining close readings of these three women's experiences with a broad overview of other cases from the literature, this article attempts to come to terms with when, how, and why alleged lesbians faced instances of both persecution and tolerance from Nazi officials.

In so doing, I identify four modes in the relationship between lesbians and the Nazi state, and argue that women who fell into these four different categories faced radically different responses from party and state officials. First, there are cases of persecution that occurred in the context of other persecutions, that is, Jewish lesbians who were incarcerated or murdered primarily because of their Jewish identity, but whose sexuality nonetheless seems to have played a role in their persecution. Second are women who behaved in certain ways that became legible to Nazi officials as threatening to the social order, that is, women who appeared to build cliques or seduce young women into lesbianism. These perceived behaviors ran parallel to justifications for the persecution of gay men and had roots in the discourses of earlier eras. These women could be reprimanded or punished, but rarely faced the same draconian forms of persecution as the first group.

Third, some lesbians came to authorities’ attention only because they were alleged to have committed some other conventional crime, such as larceny. Although sexual identity crops up in police or court files dealing with such cases, it rarely seems to have affected police investigations or the court's judgment. Fourth and finally, some lesbians were denounced as such to the police, but their cases had no extrinsic factors of interest to officials. Those women usually faced no punishment. These four modes are, of course, necessarily blurred and overlapping—what I hope to capture in the term heterogeneous persecution. I do not contend that they were clearly defined categories, but rather that they represent certain trends in how officials thought about and treated lesbians.

To make these claims, the paper is divided into four sections. The first section offers an overview of the sexual-criminal law in Nazi Germany and explains why the regime declined to criminalize female homosexuality. The subsequent three sections consider each of the first three modes I identify. The fourth section also considers lesbians whose cases involved no extraneous factors. Each section begins with an in-depth analysis of one case study before zooming out to consider other cases drawn from the literature. This paper aims to offer a model of persecution, discrimination, and tolerance that weaves together thirty cases from Germany, excluding Austria, that scholars have uncovered over the last several decades.

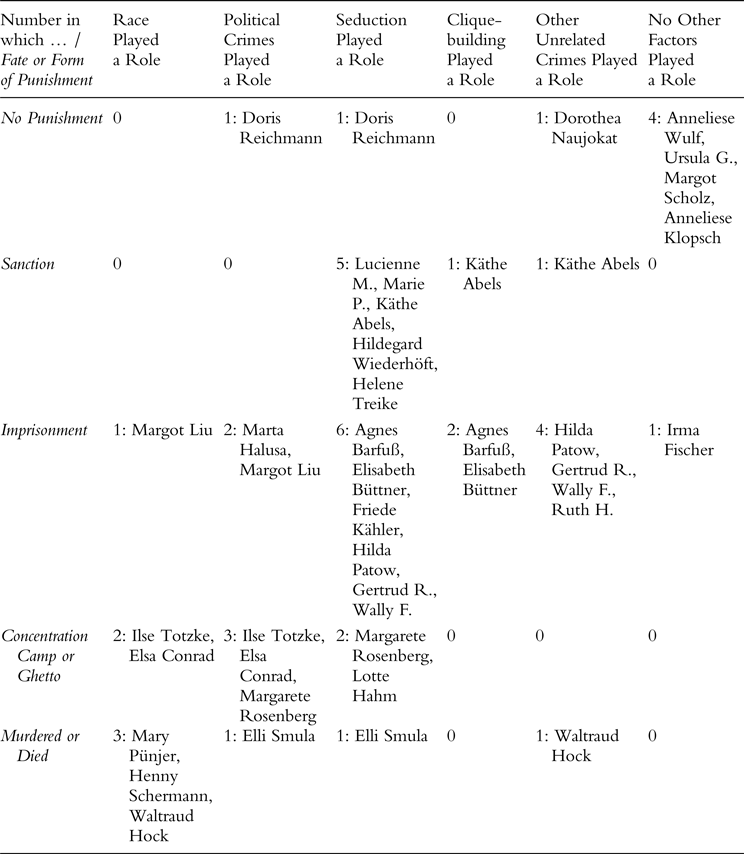

To aid in this contextualization, I have represented these thirty cases in a chart (see Table 1). The diagram illustrates in how many cases race, political crimes, seduction, clique-building, other crimes, and no other factors played a role, and in how many of each of those there was no punishment, sanctioning, imprisonment, incarceration in a concentration camp or ghetto, or murder or death. In addition to qualitative comparisons, this quantitative approach helps us comprehend the curious mixture of persecution, tolerance, and apathy that characterized lesbian life and officials’ responses to female homosexuality in the Third Reich.

Table 1. Cases of Lesbianism Indexed by Type of Case and Most Extreme Punishment or FateFootnote 20

In making these claims, I seek to move away from language critiquing the ability of persecution, victimhood, or tolerance to describe or explain the history of female homosexuality in Nazi Germany. Instead, I suggest a model of why and how different women, whom state actors considered to be lesbian, faced radically divergent reactions to their sexuality from police, prosecutors, courts, and party organizations. This approach not only illustrates the overlapping and competing elements of the Nazi state—and their capricious ability to deal with outsiders who fell into their sights—but also the different modalities of persecution that women, who became legible to state actors as lesbians, faced in Nazi Germany. Ultimately, I contend, this model makes clear that lesbians did suffer from heterogeneous persecution that was often intersectionally situated and combined elements of discrimination, tolerance, and oppression.Footnote 21

Homosexuality and Criminal Law in Germany

Although histories of homosexuality in Germany often start with §175, laws regulating same-sex activity stretch far further back in central Europe. The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, promulgated by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1532, prescribed death at the stake for both male and female sodomites.Footnote 22 Although there are few records of courts applying the measure to women, historians have long known of the case of Catharina Margaretha Linck, whose masculine dress and marriage to a woman led to their execution in 1721.Footnote 23 Although the General State Laws for the Prussian States from 1792 abolished this death penalty, it continued to criminalize both male and female same-sex acts.Footnote 24

In 1851, however, the young Prussian parliament promulgated a new penal code. Significantly, its law against same-sex acts, §143, only prohibited those between men. In 1872, after Germany's unification, §143 was adopted in the new penal code as §175. Its language criminalized “unnatural fornication (widernatürliche Unzucht)” between men, which, as courts repeatedly held, only banned “‘intercourse-like’ (beischlafähnliche) acts.”Footnote 25 This language meant convictions could be quite difficult to win in court, as prosecutors needed to prove either oral or anal penetration had taken place. Like its predecessor, §175 did not criminalize female homosexuality.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they were perceived by many as a movement friendly to homosexuals.Footnote 26 Germans thought as much because Ernst Röhm, Hitler's close friend and the chief of staff of the paramilitary Storm Troopers (Sturmabteilung or SA), was widely known to be gay.Footnote 27 Nonetheless, the Nazi regime moved to shutter gay and lesbian bars and periodicals in the spring of 1933.

On June 30, 1934, Hitler had Röhm murdered in what became known as the Night of Long Knives. Although he did so to appease military leaders wary of Röhm's power and of the strength of the SA, Hitler used Röhm's homosexuality as a justification for the purge.Footnote 28 In an address to the Reichstag on July 13, the dictator insisted Röhm had gathered about him a cabal of homosexuals who were plotting to overthrow the government. “The worst,” he told fascist deputies, was that widespread homosexuality in the SA “generated the nucleus of a conspiracy against not only the morality of a healthy Volk but also against the security of the state.”Footnote 29

Although this fear started as a somewhat implausible justification for an internal party purge, it became, in the words of Geoffrey Giles, a “fictitious yet nonetheless powerful dread [that was] derived from Hitler's mendacious analysis of the Röhm Putsch, reinforced by Himmler and passed on down the ranks of the Nazi movement.”Footnote 30 The ideologue Rudolf Klare warned in his 1937 doctoral dissertation, Homosexuality and Criminal Law, of an “inverted army” and of “inverted youth,” contending that, until recently, “homosexuals occupied influential positions, that homosexuals dominated areas of public life.”Footnote 31

These fears were fed by the belief that homosexuality was, by and large, not a congenital trait, but rather a learned behavior.Footnote 32 Drawing on discourses from the Weimar and imperial eras, Nazi thinkers claimed that gay men seduced male youth into homosexuality. Thus, they feared homosexuality could spread, in particular within male-dominated organizations such as the military, the SA, and the SS, which in turn could pose a threat to the regime's hold on power.Footnote 33

On June 28, 1935, around a year after the Röhm purge, the government promulgated a new version of §175. Whereas the old one had only banned intercourse-like acts, the new law banned all acts between men that could be perceived as homosexual.Footnote 34 Moreover, the regime added a new subparagraph, §175(a), which, among other things, criminalized “a male person over twenty-one years who seduces a man under twenty-one years, in order to fornicate with him or allow himself to be misused for fornication by him.”Footnote 35 That is, the regime hoped to cut off the means by which it believed homosexuality spread. Those convicted could face terms of prison with hard labor (Zuchthaus), a far harsher punishment than the prison (Gefängnis) mandated for ordinary §175 convictions. Some fifty thousand men were convicted under §175 and §175(a) in the Nazi period. Approximately ten thousand were sent to concentration camps, where many wore the now-infamous pink triangle.Footnote 36

But in spite of protests from a few individuals, including Klare, the law did not criminalize female homosexuality. Jurists ultimately chose not to for reasons grounded in the regime's complex view of and relationship with German women. Rooted in a deeply misogynistic worldview, it considered adult, Aryan women first and foremost as mothers and wives. As such, the state largely excluded women (once they had married and begun raising children) from public and political life.Footnote 37 Thinkers also tended to believe women were not possessed of an independent sex drive. For these reasons, Nazi officials insisted that women were not active in settings where they could be seduced or seduce others. In the words of Ministry of Justice official Leopold Schäfer, because of women's “less influential position in state and public offices,” female homosexuality posed less of a threat. Neither seduction of youth nor conspiracy seemed as widespread or urgent a problem among lesbians as among gay men.Footnote 38 Thus, female homosexuality's continued licitness stemmed not from a lack of animus, but rather from a misogynistic outlook that fundamentally discounted female sexual and social agency.

Intersectional Persecutions

On December 22, 1941, just three days before Christmas, Lina Baumgartner wrote to the director of the Frankfurt-Preungesheim women's prison. Her daughter, Waltraud Hock, was supposed to have returned from the institution, where she had been serving a three-month sentence for refusing to work (Arbeitsverweigerung). “She should have already been released on the 17th,” Lina scribbled. “I'm waiting for her still today, am in great agitation about my child.”Footnote 39

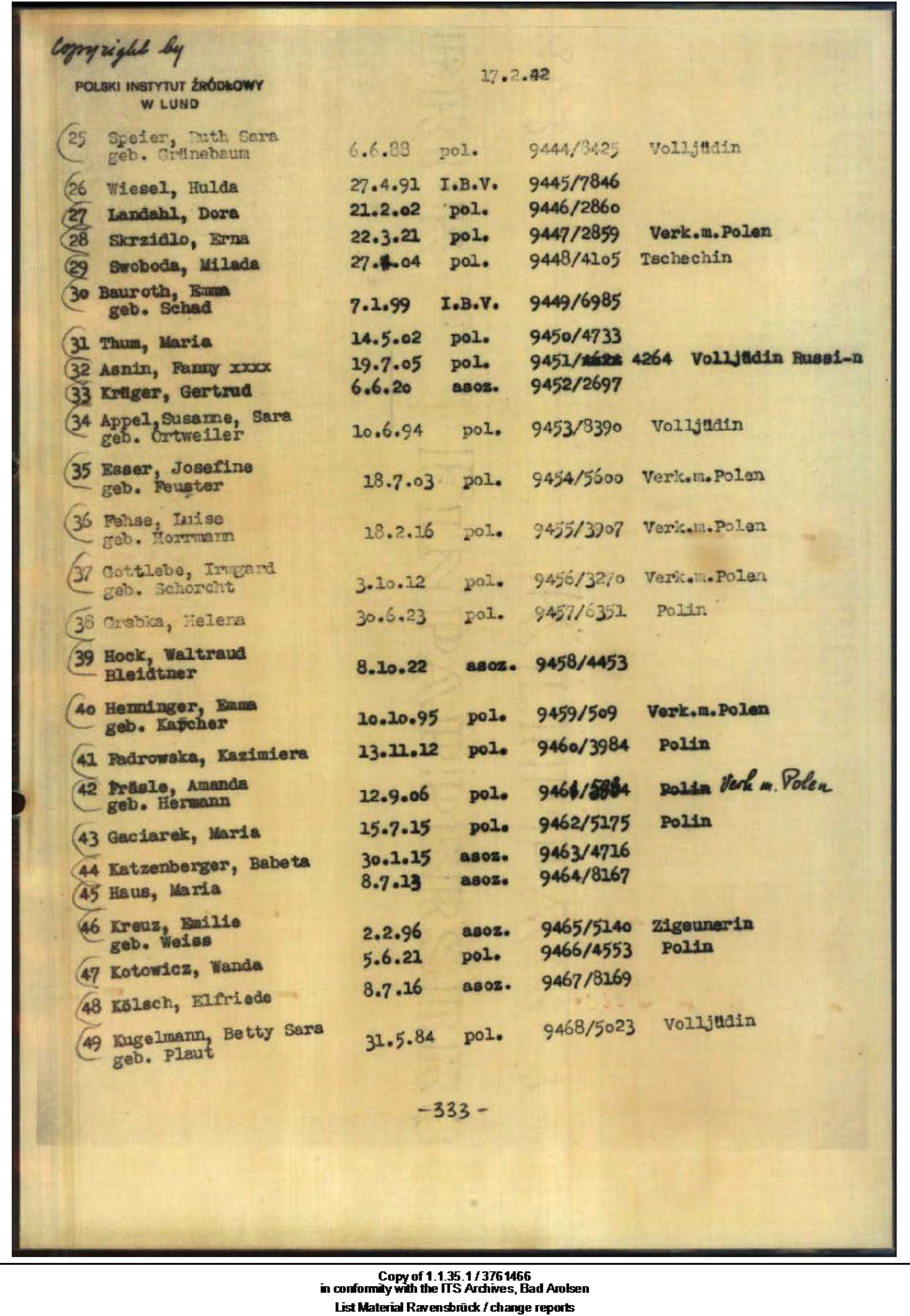

On Christmas Eve, the first matron of the prison wrote back, telling Lina that Waltraud had been released on the 17th and immediately transferred into the custody of the Wiesbaden criminal police (Kripo). What the letter did not say is that the police had already decided Waltraud would be sent to a women's concentration camp after she completed her prison term.Footnote 40 Records indicate she was registered as an “asocial” at Ravensbrück, the largest female camp in Nazi Germany, just north of Berlin, shortly after her prison sentence ended (see figure 1).Footnote 41 At some point thereafter, she was transferred to Auschwitz, where she died in March 1943.Footnote 42

Fig. 1. Item 39 from a list of women incarcerated at Ravensbrück, dated February 17, 1942, shows Hock registered as an asocial in the camp. Courtesy of the ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen.

The police had first arrested Hock, who was born on October 8, 1922, earlier in 1941.Footnote 43 In a short biography written out in her own hand on October 26, 1941, she explained why she was in police custody. At approximately the age of nineteen, she had gone to the employment office to ask about work as a conductor for the Wiesbaden public transportation service. Instead, officials conscripted her to work on a farm as part of the war effort. She showed up at the farm soon thereafter and told the farmer “very openly that agricultural work would not be enjoyable for me.” The farmer, in Hock's recounting, replied, “then it's not useful [for you to come], because one should love the work they do.”Footnote 44

Hock interpreted the farmer's response as a sufficient excuse to stop showing up to work. She simply remained home, apparently hoping that the employment office would take the hint and reassign her. After receiving two letters from that office, she was arrested and sentenced to three months in prison for refusing to work. She promised that, after her sentence was completed, “I will immediately get to work.”Footnote 45

Once in the Nazi penal system, however, other information about Hock began to catch functionaries’ attention. She had had to repeat second grade, for instance. According to the NSDAP Volkswohlfart Jugendhilfe (National Socialist People's Welfare Youth Services), to which the women's prison applied for an assessment of her case, Hock's academic problems stemmed from her “laziness and indifference.”Footnote 46

Moreover, although Hock had written that she was the daughter of her mother's ex-husband Karl Bleidtner, party officials indicated that she was, in fact, the daughter of a “colored (farbiger) occupation soldier, ostensibly American.”Footnote 47 The Jugendhilfe report alleged that her mother Lina Baumgartner was “animalistically libidinal” and had been sterilized, a remedy the Nazi state applied to several hundred thousand supposedly asocial and racially unfit Germans.Footnote 48 Just as bad, Baumgartner's husband had been taken into political protective custody in 1933 and hanged himself.Footnote 49 Like her daughter, Baumgartner seemed to have fallen into the penal apparatus for several overlapping reasons. The 1935 Nuremberg prohibition on sex between those defined as Jews and those defined as Aryans did not criminalize sex between Black and white Germans.Footnote 50 Nonetheless, such acts were taboo in the racial state. Although the file does not specify the precise reason for Baumgartner's sterilization, it is not difficult to understand how a health court, confronted with her former relationship with a likely Black occupation soldier and her multiple other relationships, would have concluded that, under the terms of the July 1933 Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring, she should be sterilized.Footnote 51

The Jugendhilfe further noted that although Waltraud had married one Peter Hock (at the age of sixteen) and had a daughter also named Waltraud, “she spent everything on herself [and] did not care for the child.” In 1941, the marriage ended. She had also been sentenced in 1940 to two weeks in prison for stealing 20 reichsmark (RM).Footnote 52

Furthermore, the assessor mentioned that Hock's mother had been imprisoned for “illicit contact with prisoners of war”—likely sexual contact, which, as Elizabeth Heineman contends, was a serious problem for the Nazi government.Footnote 53 Both mother and daughter, the report insisted, had “entertained lovers in their apartment, but were not to be caught, because they were so sneaky.” Some of Hock's lovers, we are left to assume, were allegedly women, because the report, without expanding or providing any form of evidence, described her as a “lesbian (Lesbierin).”Footnote 54

The report offers further clues as to why someone sentenced to three months in prison for evading work would have wound up dead in Auschwitz. Just a few lines under the note that Hock was lesbian, the report described the “inner causes of the crime” as “moral rot.” In the report's section asking, “Do you believe benevolence or sternness will be effective,” the official had typed “sternness.” When asked, “Where should the person be brought after their release,” they typed “workhouse or camp.”Footnote 55 It is not surprising, then, that a few weeks later, the Wiesbaden criminal police decided that she should indeed be sent to a women's concentration camp, where she would be registered as a so-called “asocial.”Footnote 56

Given this picture of Hock, which, because mediated through the lens of police and other bureaucratic records, is necessarily indistinct, it becomes less astonishing that she wound up in the camp system. National Socialism had come to power in Germany in part on the strength of its vision for an Aryan racial community or Volksgemeinschaft.Footnote 57 Because the concept of the Volksgemeinschaft remained a key tenet of Nazi ideology, the idea of asociality—of those who did not belong in the community for some not-quite-identifiable reason—became a potent way to define non-belonging. Scholars have long noted that asociality was a flexible category, even after it was partially codified in Heinrich Himmler's 1937 Preventative Detention Decree. Black Germans, homosexuals, prostitutes, single women, Roma and Sinti, and others could fall under its umbrella and be whisked away to a concentration camp, where they often wore a black triangle.Footnote 58 In fact, asocials made up a disproportionately high number of those incarcerated in camps between 1936 and 1941, comprising up to 70 percent of all camp prisoners in late 1938.Footnote 59

Examining Hock's acts and identities, alongside her evaluation by Nazi functionaries, it becomes clear how easily she fit into the nebulous concept of the asocial. Her supposed female homosexuality likely played at least some part in this determination. But there were several other factors at play, including her alleged laziness and unwillingness to work. The Nazi state classified thousands of individuals as “work-shy”—another ill-defined and therefore flexible concept—sending many to workhouses or to concentration camps.Footnote 60 By 1938 Sachsenhausen had more than six thousand “work-shy” inmates.Footnote 61 Hock's mother's background also made her a prime candidate for designation as an “asocial.” In a state that Edith Sheffer describes as a “diagnosis regime,” Hock was diagnosable as suffering from numerous biological defects and moral failings that made her particularly vulnerable to incarceration in the extrajudicial system of the concentration camps.Footnote 62

Moreover, her status as the daughter of a likely Black occupation soldier undoubtedly played a role in Hock's eventual murder. Although Black Germans were not targeted in the same manner as Jews, they faced discrimination and persecution of various sorts. In the Weimar years, right-wing propaganda had repeatedly attacked the so-called Rhineland bastards, offspring of German women and French colonial soldiers born during the Rhineland occupation of 1923–1925.Footnote 63 After the seizure of power, Nazi officials labeled some Black Germans asocial. Many, in particular the Rhineland children, were sterilized or wound up in concentration camps.Footnote 64 Some, such as Hans Massaquoi, survived the Nazi period relatively unscathed and, in Massaquoi's case, lived to pen a famous memoir about growing up Black under Hitler.Footnote 65 Others, such as Jonas N'Doki, who was accused of sexually assaulting white German women in 1939 and 1941, were put to death.Footnote 66 Because the Nazi government never settled on a unified policy vis-à-vis most Black Germans, their treatment was, in Tina Campt's words, “neither systematic nor coherent.”Footnote 67

That incoherence is precisely why they could fall into flexible, intersectional categories of persecution such as the asocial. As Kimberle Crenshaw, who coined the term intersectionality, notes, “Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.”Footnote 68 Adapting this framework to the Nazi state, historians have come to see that persecution did not fall along rigidly hierarchical lines, especially for non-Jewish victims, but rather that different identities and behaviors combined in ways that put individuals in more or less danger of being sent to concentration camps or murdered. In cases such as Hock's, and others discussed in the following, persecution was not predicated on a single identity or act. Rather, Hock's numerous, overlapping identities conspired in ways that the black and white of penal documents cannot always capture to lead her from prison to Ravensbrück to Auschwitz and, ultimately, to her death.

Hock's case resembles those other cases, which included racial or eugenic components as well as those in which political crimes played a role. Even though, to my knowledge, historians have discovered no other cases of Black German lesbians, there are numerous cases of Jewish German lesbians, most of whom met fates similar to Hock's. Margot Liu, a Jewish German lesbian who wed a Chinese man to escape deportation, is something of an outlier. To my knowledge, she represents the only known case of a Jewish lesbian who came to the attention of the authorities and avoided both death and concentration camps. She and her partner Marta Halusa, about whom both Ingeborg Boxhammer and I have written, were investigated as lesbians in 1942. They were arrested in early 1945 for political crimes, only managing to escape in the chaos of the war's ferocious end.Footnote 69

Other cases that involved race include that of Elsa Conrad, described by Claudia Schoppmann, who was a part-Jewish lesbian bar owner in the Weimar era and openly critical of Nazism. In 1935, she was imprisoned for “defamation of the Reich government,” then in 1937 sent to the Moringen concentration camp. She was released in 1938, fled to Tanzania, and survived the war.Footnote 70 Ilse Totzke, a so-called Aryan, was arrested for assisting a Jew's flight into Switzerland and was sent to Ravensbrück in 1943. She was recorded as liberated after the war, but, according to Yad Vashem, was never located.Footnote 71

Claudia Schoppmann has also written about two Jewish women, alleged lesbians, who were murdered in the concentration camp system. Mary Pünjer and Henny Schermann were both incarcerated at Ravensbrück in 1940. In both cases, Dr. Friedrich Mennecke, a doctor overseeing the 14f13 euthanasia program who selected its victims at Ravensbrück, noted down their Jewishness and their homosexuality. In Pünjer's case, Mennecke wrote, “married full-Jew. Very active (‘saucy’) lesbian” (“verheiratete Volljüdin. Sehr aktive (‘kesse’) Lesbierin”).Footnote 72 Schermann he described as a “compulsive lesbian” and a “stateless Jew.”Footnote 73 Officially, Pünjer died on May 28, 1942, Schermann two days later. Schoppmann indicates that they were quite possibly gassed months earlier at the nearby Bernburg sanatorium. Although their place in the Nazis’ racial hierarchy was the determining factor in their incarceration and death, Mennecke's notes suggest that their sexuality may have played a not-insignificant role in the decision to murder them.Footnote 74

Although Waltraud Hock's case did not involve political crimes per se, lesbians who were found to have allegedly defamed the state or hampered the war effort also met harsh punishments. Two such cases resulted in concentration camp incarceration or death. Margarete Rosenberg and Elli Smula were both “Aryan” employees of the Berlin Public Transportation accused of having taken “fellow workers with them back to their place, plied them with alcohol, and then performed homosexual intercourse with them.” Because this seduction impeded the ability of the employees to “carry out their duties,” in the Gestapo's words, “the operation of the tram station Treptow was severely compromised.”Footnote 75 As Schoppmann relates, the secret police accused them of “subversive conduct” and both were incarcerated at Ravensbrück as political criminals. Rosenberg survived, whereas Smula died on July 8, 1943.Footnote 76

Thus, turning to Table 1, cases that involved either race or political crimes typically ended in severe punishment. These fates suggest, unsurprisingly, that lesbians who were not considered Aryan, or who were arrested for “subverting” the regime, faced punishments similar to those of political or racial “criminals” who were not lesbian. That is, these women were persecuted, but their sexuality does not seem to have played the defining role in that persecution.

Nonetheless, there is good evidence that sexuality could play a supporting role in such cases. Laurie Marhoefer demonstrates, for instance, that Ilse Totzke came to the attention of the local Gestapo because neighbors had denounced her for being lesbian. Similarly, Mary Pünjer's and Henny Schermann's alleged lesbianism showed up in the reports that led to their likely murders in the 14f13 program. It is, therefore, entirely reasonable to believe that Hock's lesbianism, although not explicitly connected to her fate, played a part in bureaucrats’ determination that she should be sent to Ravensbrück. As Hájková has suggested, such cases illustrate how intersectional persecution functioned in Nazi Germany.Footnote 77 These persecutions were not merely additive, but rather represented a multiplicative confluence of risk, to use Marhoefer's term. That is, in some such cases, one cannot simply point to one identity or behavior that led to incarceration or death. For Hock, her mother's alleged “libidinousness,” her racial classification, her unwillingness to work, and her alleged homosexuality all likely contributed to her fate.

Lesbian Seduction and Lesbian Cliques

Käthe Abels, born in Duisburg in 1892, was forty-two years old when she opened a private mental hospital in Joachimsthal, a small village near Berlin, with her friend Maria Handtke.Footnote 78 A so-called Aryan and member of the National Socialist Party, Abels occupied a considerably more privileged position in Nazi Germany than Hock.

Abels had run the hospital successfully for eight years, from 1934 to 1942, when one of her employees, a young woman named Erika Schwabe, committed suicide. Her death set numerous inquiries and trials in motion that would eventually see Abels, an alleged lesbian, removed from the Nazi Party and deprived of her hospital.Footnote 79

Abels's neighbors had long suspected that she was drawn to women. As the director of the hospital, she was responsible for hiring nurses and houseworkers. At a certain point, others in Joachimsthal noticed that she often employed women who were unqualified for their positions. Courts later asserted that she “systematically wooed younger women, who appealed to her, either for rest and relaxation or with the pretense of a particularly favorable job.”Footnote 80 Records suggest she succeeded in employing at least four women in this way.

Whether Abels considered herself a lesbian is somewhat unclear. Other than an affidavit from Abels herself, in which she protested her heterosexuality, the evidence in her file was compiled and presented by party and judicial officials. Nonetheless, the truth of her identity is somewhat beside the point—as we will see, she behaved in ways that rendered her legible to state functionaries as a lesbian. Abels herself insisted she was the victim of “gossip that is, indeed, much more deeply rooted in small towns than in larger communities [and] seizes on single women with particular relish.”Footnote 81

In 1942, she had an argument with her neighbor, one A. Kania, in which he called her “old sow, gay sow (schwule Sau).” Abels had allegedly already tried to seduce his daughter Eleonore in 1937, which might have been part of his complaint.Footnote 82 Their spat eventually led them to file countervailing slander suits against each other, which resulted in the district court holding that Abels was, indeed, lesbian.Footnote 83 Even the assistant mayor of their small community, Abels complained, was spreading gossip about “things that are in no way proven, such as, for example, lesbian predilection, which I continue to dispute.”Footnote 84 Whatever Abels thought of her own sexuality, her behavior made her intelligible to her neighbors and, eventually, to state and party officials as a lesbian.

In October 1941, Abels hired a woman named Martha Godemann. Godemann, who was forty-four years old at the time, met Abels in 1940, because her father was a patient at her hospital. Godemann lived in Berlin and Abels frequently drove there to visit her. According to the Eberswalde district court (Amtsgericht), Abels would “spend the evening and night in [Godemann's] apartment and drive back to Joachimsthal the next morning.” Abels herself wrote in 1944 that Godemann attempted to seduce her “with wine and champagne.” Shortly thereafter, Abels hired her as a nurse, in spite of the fact that she had been trained as a tailor.Footnote 85

Once employed in Joachimsthal, Godemann apparently slept in Abels's room. In the words of the Brandenburg Nazi Party district court, an “abnormal relationship” developed between them.Footnote 86 But less than a year later, in August 1942, she and Abels had a falling out, and Godemann left the sanatorium. Their fight, Abels wrote, was grounded in the “supercilious, unbearable character of this employee [which made] a lasting engagement in my home simply unbearable.” She later alleged that Godemann had “sworn, that she would not rest, until I myself and my care home were ruined.”Footnote 87 And time did not heal the wounds between them. Two years later Abels wrote, in an attempt to discredit Godemann in court, that she was a “non-party-member who is under powerful Jewish influence.”Footnote 88

It seems possible that another woman touched off their argument. At some point between 1940 and the fall of 1942, Abels met a young shoe saleswoman named Erika Schwabe, who was also allegedly lesbian and also lived in Berlin. Abels convinced her to move to Joachimsthal and work in her home. Schwabe did this in September 1942, at the age of twenty-seven, only one month after Abels's falling out with Godemann. Three months later, on December 7, Schwabe took twenty-nine veronal tablets and killed herself. Her death led to at least three inquests and trials.Footnote 89

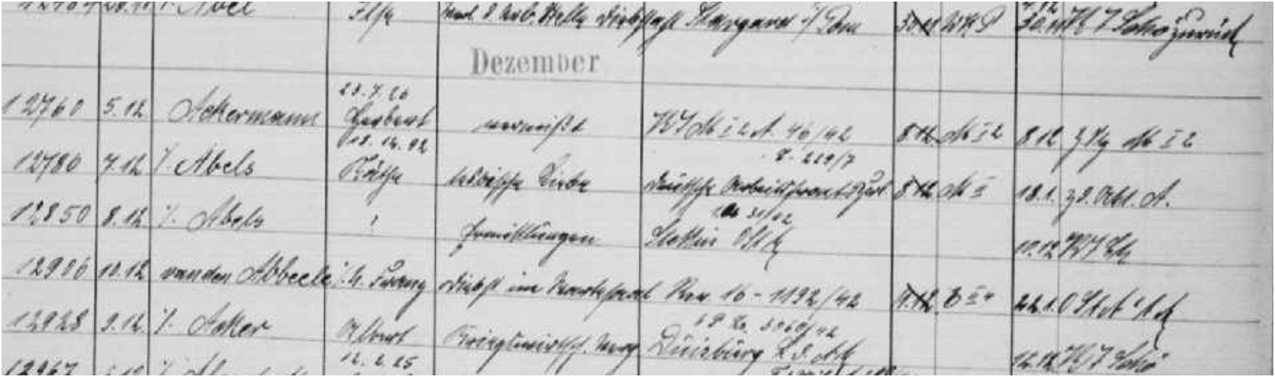

Immediately after Schwabe's suicide, Abels's name showed up in the records of the Berlin criminal police under the designation “lesbian love” (see figure 2). Though neither the Berlin records nor the court records in Potsdam indicate why it did, it is likely that the criminal investigation, which ensued after Schwabe's suicide, relied on resources from the Berlin criminal police. The investigation was led by the state's attorney of the Brandenburg district of Prenzlau, who thought it possible that either Abels had been neglectful in her management of the sanatorium or that her sexual interest in Schwabe had somehow driven the young woman to suicide. Although his report indicated that Abels was “a lesbian,” it did not ascribe fault in Schwabe's suicide to her.Footnote 90

Fig. 2. The K-index of the Berlin criminal police, which recorded postal communication regarding individual defendants and convicts, shows Abels's name appearing on December 7, 1942, with the annotation “lesbian love.” Source: Landesarchiv Berlin, Pr. Br. Rep. 30 Bln C, Tit. 198 H Gen, Index 1 1942 Aa-Cz. Courtesy of the Landesarchiv Berlin.

Soon thereafter, Martha Godemann, who still bore a grudge against her former employer, used Schwabe's suicide to denounce Abels to the local party. The denunciation led to an investigation by the leader of the local party arbitration board, after which Abels was accused of “having sustained same-sex intercourse with women up until the present day.”Footnote 91

On June 22, 1944, the Brandenburg party district court (Gaugericht Mark Brandenburg) determined that Abels had had “illicit intercourse” with Maria Handtke, her business partner. It also established that Abels had had an affair with Godemann and had attempted to woo her neighbor's daughter Eleonore. The court further indicated that at Schwabe's funeral, Abels had tried to seduce Elvira Piesl, a friend of Schwabe's. The party judges insisted that Abels constantly attempted to collect lesbian friends and lovers.Footnote 92 Although the court held that some of these women were also lesbian, there is no evidence that any of them faced persecution, punishment, or sanction because of it.

But the judges plainly disapproved of Abels's behavior. Their final decision is worth stating in full because it provides such a clear explication of why the party considered female homosexuality unacceptable:

The accused has herewith forfeited the right, through proven abnormal sexual disposition and activities, to continue to remain in the Party. The NSDAP fights every sexual degeneration, whether or not it is criminally actionable. Female same-sex activity represents a significant threat to marriage and the natural disposition of the woman to motherhood.Footnote 93

The judgment is of particular interest because it represents one of relatively few cases, of which we know, in which a lesbian was punished or sanctioned specifically because of her sexuality. As the judges noted, female homosexuality was not criminally punishable and Abels's case therefore represented something of an anomaly.

The party court contended that lesbianism was a “sexual degeneration” that threatened both motherhood and marriage. Now, Abels, a single, forty-four-year-old woman, was not likely to bear any children. But the court recognized that her attempted seductions of younger women threatened their ability to marry and bear Aryan children for the Reich. Abels had tried (and in many cases succeeded) to “pursue” the twenty-seven-year-old Schwabe, twenty-five-year-old Kania, and twenty-eight-year-old Piesl and to keep them “under constant psychological pressure.” The court argued she had attempted to make the women “completely dependent (hörig) on her” and had even succeeded in effecting a separation between Piesl and her husband.Footnote 94

This language drew on long-standing stereotypes about lesbian women.Footnote 95 In fact, in 1911, the Reichstag had considered recriminalizing female homosexuality, in part because women's economic and social emancipation had allegedly enabled the spread of lesbianism through seduction.Footnote 96 The court's ruling also resonates with language used to describe and persecute gay men in the Nazi era. As the regime had promulgated §175(a)-3 to outlaw the supposed “seduction” of youth by male homosexuals, so too the party found that Abels had attempted to seduce young women into lives of lesbianism. In general, the party believed lesbians did not behave in this way, and therefore did not pose as great a threat to society or the state. When they did, however, Abels's case suggests that women could face sanctions motivated specifically by their sexuality.

Moreover, Abels's trial illuminates the working of Nazi party courts, about which little has been written. The NSDAP had created internal Investigation and Adjustments Committees as early as 1925, which eventually evolved into a comprehensive party judicial system by the mid-1930s. Unlike the state court system, which dealt with criminal and civil violations, or the infamous people's court (Volksgerichtshof), which the fanatical Roland Freisler directed and which prosecuted so-called “political offenses,” the party courts were a mechanism to keep party members in line.Footnote 97 Organized into a three-tiered structure of local and district courts headed by a Party Supreme Court, the system only had jurisdiction over members, punishing their noncompliance with party rules and expectations.Footnote 98 Abels's case intimates that future research into lesbianism in Nazi Germany might do well to look at the records of party courts.

Käthe Abels was no longer a member of the Nazi Party, although she later wrote, “I remain a National Socialist either way.”Footnote 99 But on October 20, 1944, the Joachimsthal mayor went to court to take away her license to operate the sanatorium. In language reminiscent of the paranoia around gay cliques, he accused Abels of having “almost constantly gathered around herself a circle (Kreis) of people who are abnormally inclined and dependent (hörig) on her, in order to be able to pursue her abnormal feelings and activities in the most inconspicuous way possible.”Footnote 100 One of these women had been Erika Schwabe, who, he alleged, might have killed herself because of the sexual pressure put on her by her employer. “In the case of Erika Schwabe's suicide,” the mayor wrote, “sexual-perverse occurrences, which can be found in the defendant's predilections, play a not insignificant role.”Footnote 101

The administrative tribunal, to which the mayor brought the complaint, agreed on December 6, 1944. Like the NSDAP court, this body held that Abels was a lesbian who systematically hired younger lesbian women to work in her establishment. It asserted that this practice led “to altercations and disputes and finally to the unpeaceful breaking-off of employment.”Footnote 102 Although it did not blame her directly for Schwabe's suicide, the judges did hold that “the defendant exploited the relationships with her female employees through their economic dependency in order to make these individuals subservient to her perverse sexual cravings” and that this established a “deficiency of reliability,” which was grounds to deprive her of the concession.Footnote 103

Abels's case is radically different from Hock's. To begin with, there were no racial, eugenic, or political crimes at play in Abels's tribulations. She was a so-called Aryan, who was not accused of having associated with non-Aryans. She had not slandered the regime—in fact, she was an NSDAP member! And officials were not concerned that she would produce undesirable offspring.

Rather, we see here a second mode of the state's relationship with lesbians. The language that courts, prosecutors, and the party used to describe Abels in many ways mirrored its thinking about how and why gay men posed a threat. Abels was accused of having formed a Kreis of lesbians in her institution—precisely the political concern that helped motivate Nazi antigay animus. She had corrupted the position of trust with which the local government had endowed her. Moreover, just as National Socialists argued that gay men seduced younger men to turn them into homosexuals, so too Abels was accused of having seduced young women, thereby threatening marriage and motherhood. As in cases of the alleged seduction of male youth, the intergenerational nature of some of Abels's relationships helped to make them legible to officials as instances of lesbian seduction.Footnote 104 Officials thus saw her alleged homosexuality as a problem not necessarily on moral grounds, but rather because of the social danger it posed.

Thus, in Abels's case, state and party functionaries clearly worried about the effects of her sexuality on the social fabric. As with gay men, officials worried that Abels had abused her prominent social position to sate her sexual appetites. In fact, Abels's status is precisely what attracted attention to her and opened her up to prosecution by a party court. Just as gay NSDAP members often faced harsher punishments under §175, so too Abels's party membership made her more vulnerable to accusations of clique-building and seduction.Footnote 105

Moreover, Abels's case suggests that, in such instances, lesbianism took center stage as a problem for Nazi bureaucrats. In these examples, lesbianism created problems for society that the state believed it had to address. When we look back to Table 1, we can see that this trend largely holds in other similar cases. Of the fifteen cases that involved accusations of seduction and Hörigkeit (sexual submission), almost all of them resulted in some form of punishment.

The closest case is probably that of Agnes Barfuß and Elisabeth Büttner, described by Jens Dobler. They were, along with Barfuß's daughter and daughter's friends, investigated for “suspicion of seduction of lesbian relationships.”Footnote 106 Dobler does not note that they were explicitly accused of building a circle of lesbians, but does describe them as having created “a lesbian network.”Footnote 107 Furthermore, as part of the investigation, Agnes's daughter Hedwig, who worked at the Berlin Siemens factory and met many of her lovers there, told the Gestapo, “Siemens is teeming with lesbian pairs.”Footnote 108 Elisabeth Büttner was sentenced to three months in prison and Agnes Barfuß to nine months, both for severe procurement (Kuppelei), the crime of aiding and abetting the commission of extramarital sex. In essence, the two women were prosecuted for having allowed their daughters and their female friends to engage in same-sex activity.Footnote 109 Although Kuppelei, which §180 of the penal code prohibited, offered a legal basis for punishing Barfuß and Büttner, Dobler's account suggests the Gestapo were particularly worried about seduction and the spread of lesbianism.

Also similar to Abels's case is that of Frieda Kähler, a Hamburg nurse of whom Schoppmann has written. A doctor had written to the criminal police in August 1936, reporting that nurses at a local home “sexually assault patients, to whom they give morphine in order to break their willpower.”Footnote 110 As a result, Kähler was sentenced to nine months in prison, a fine, and a work ban under §174 of the penal code, which prohibited sexual relations with dependents. Kähler's fate, Schoppmann argues, illustrates how officials could punish lesbians who purportedly had affairs with dependents.Footnote 111 It reveals—as do many of these cases—how, in the absence of a law prohibiting female homosexuality, other paragraphs of the penal code could be applied against lesbian women when officials came to see their behavior as dangerous.Footnote 112

Likewise, the prominent lesbian activist Lotte Hahm was supposedly accused of “seducing a minor” in 1933 and sent to prison. Two years later, for reasons unknown, she was sent to Moringen concentration camp. Unfortunately, the details of Hahm's travails are lost—Schoppmann relies on oral history to reconstruct her story.Footnote 113 Interestingly, after her release from Moringen, Hahm became the leader of a lesbian sports club in Berlin called “Sonne.” But police files about the group, although they mention Hahm and her “leading role in the [Weimar] homosexual women's club ‘Violetta,’” do not note her prior convictions or incarceration at Moringen.Footnote 114 Whatever the truth of Hahm's case, the recollections of Schoppmann's witnesses are certainly plausible.

Of course, some cases that involved accusations of seduction or Hörigkeit did not result in any form of punishment. These include the case of Doris Reichmann, whose experiences Kirsten Plötz uses to interrogate practices of denunciation under Nazism. Reichmann was a gymnast accused of being lesbian in 1933. Although both her alleged Hörigkeit to another woman and accusations that she belonged to the Communist Party show up in the letter denouncing Reichmann, she ultimately was not punished.Footnote 115 Likewise, Claudia Schoppmann describes how Helene Treike was accused of being the “seducer” of her partner Hildegard Wiederhöft in March 1940. Although they were not imprisoned, the Gestapo did register them and advise them to separate. Records further indicate that Treike was placed under police surveillance.Footnote 116

In the case of Lucienne M. and Marie P., French workers at the Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG in Berlin), Marie was accused of having seduced Lucienne (as well as attempting to seduce other women). Marie was threatened (though not punished) with §183 of the penal code, which sanctioned “public indecent actions,” and both women were sanctioned insofar as they were moved to separate camps.Footnote 117 Gertrud R., a Dresden masseuse, was in 1941 accused of having seduced younger women. After a public altercation with her ex-girlfriend, Wally F., a court sentenced both women to police custody for “gross mischief (groben Unfug).”Footnote 118

In cases such as these, when accusations of seduction were at play, the German penal system could punish or sanction lesbian women for the fact of their sexuality (or for acts that their sexual predilections had led them to commit). Further evidence of such preoccupations is, in fact, to be found in the February 17, 1936, police account of a party thrown by Lustige Neun. Reporting on the group's “Bad Boys Ball” (Böser Buben Ball), the detective wrote, “A further danger is, that this kind of woman will attempt to find new, unencumbered members of the same sex (unbelastete Geschlechtsgenossinnen), whom she can then lead into immoral corruption.”Footnote 119 The fear of seduction clearly shaped how Nazi officials conceived of lesbianism and its place within and without the Volksgemeinschaft. When female homosexuality began to tear at the social fabric and threaten the institutions of motherhood and marriage, state actors could and did intervene.

Tolerance and Persecution

Ruth H. and Inge G. represent yet another type of case. They were both born in Dortmund, Ruth in 1922 and Inge in 1924. Ruth's father was a sports teacher, and Inge's was a mill worker. Both seem to have had relatively unremarkable upbringings but ran into difficulty with their parents and left home at early ages.Footnote 120

Ruth went to work for the post office as a telephone assistant in 1940, but soon began to accumulate debts, about which she was nervous lest her mother find out. She ran away from home for the first time in 1941, at the age of nineteen, and began to work as a prostitute.Footnote 121 She contracted gonorrhea, whereupon she went to a police hospital for treatment. According to the district court in Mannheim, it was there that she met a nurse named Käthe Ruder. “With this acquaintance,” the court wrote, “it evidently became clear to her that she is inclined to lesbian love and finds no satisfaction with men. The defendant denies any pursuits of obscene (unzüchtiger) nature with women, but admits that she has this predisposition.”Footnote 122

After her treatment, Ruth again ran away from home. While traveling to Stettin, she met Inge in Dortmund.Footnote 123 They then traveled together to Cologne. According to the Mannheim court, they began to prostitute themselves there and in Düsseldorf, paying for hotel rooms with their earnings. Some nights, when they could not afford a room, they slept on park benches.Footnote 124

But they began to fall behind on payments to various hotels. At the Hotel National in Koblenz, they left an unpaid bill of 98 RM. “In order to escape unobstructed,” the judge wrote, they “threw their bags through the window onto the street.”Footnote 125 They continued on to Wiesbaden, paying where they could with prostitution and leaving bills unpaid when they could not. In Mannheim, they tried to pull a similar stunt, telling the porter at Hotel Stadt Basel that they belonged to an artist troupe and would soon be paid. While there, Ruth also stole 24 RM from an Italian man with whom she had sexual relations. On November 5, they secretly fled the hotel without paying and headed for the train station. But the criminal police caught them, and they were put on trial for fraud and prostitution.Footnote 126

One might expect that a lesbian woman working as a prostitute and swindling hotels in the process would be in no small degree of danger in Nazi Germany. After all, Waltraud Hock died for far less. Indeed, in its January 28, 1942, judgment, the court harangued Ruth and Inge for having engaged in prostitution, duped hotels, and committed larceny. But the judge also took into account their young ages (nineteen and eighteen) as extenuating circumstances. The court sentenced Inge to eleven months and Ruth to thirteen months in prison. Ruth's alleged lesbian proclivities did not enter into its ruling.Footnote 127

As in Hock's case, the Preungesheim women's prison, where Ruth was incarcerated, sent a questionnaire to the NSDAP Volkswohlfahrt, Stelle Jugendhilfe, on March 11, 1942. But for Ruth, it returned with far more favorable results than it had for Hock. The report described her as “normal” in terms of her “intellectual capabilities” and did not note that the court had determined her to be a lesbian. It indicated she was an “intelligent girl.” And, of course, she was a so-called Aryan. In answer to the question, “Is return to the family recommended?” the assessor responded “yes.”Footnote 128

The fact that Ruth's alleged same-sex proclivities entered only briefly into the official record indicates that they were not a deep preoccupation for the authorities, unlike cases such as that of Abels, who was denounced and investigated specifically for her lesbian activities. But, unlike Waltraud Hock, Ruth was condemned to no extrajudicial punishment. Although she was a prostitute who had previously required treatment for an STI (prostitutes were frequently sent to concentration camps as so-called “asocials”), the prosecutors, police officials, and judge who dealt with her case never seemed to contemplate such a course with her.Footnote 129 Whereas Hock, thanks to her race and her mother's “animalistic libidinality,” became legible to officials as an “asocial,” Ruth enjoyed protection by virtue of her “normal” upbringing. What became a fatal shortcoming for Hock was nothing more than a footnote in Ruth's case.

There are a number of similar cases, in which police arrested women for crimes that were unrelated to their lesbianism and would be considered crimes today (such as not paying a hotel bill). In most of these cases, as we can see in Table 1, these women faced terms of imprisonment. Hilda Patow, for instance, was arrested for stealing money in 1938 and acknowledged, in her interrogation by Hamburg criminal police, that she was lesbian. Schoppmann recounts that when she was sentenced to one month parole, the court noted she had likely been “seduced.” But the office for delinquent supervision (Straffälligenbetreuung) reported that Patow was also a prostitute and led an “erratic, gypsy life.” Although Schoppmann does not know precisely what happened to her between 1939 and her death in 1962, that report caused Patow to serve her sentence in Fuhlsbüttel prison. She was also threatened with further incarceration if her behavior did not improve. Patow thus represents a case between those of Ruth H. and Hock. She survived the Nazi period, clearly protected by her Aryan identity and her “decent” (orderlich) upbringing. But she was also threatened with harsher punishments than it appears Ruth ever was.Footnote 130

Another similar case is that of Wally F., the Dresden woman arrested in 1941 for starting a brawl with her ex-girlfriend Gertrud R.'s new lover. Wally was sentenced to two weeks in police custody for “gross mischief (groben Unfug).” As noted previously, Gertrud R. was also arrested and sentenced to five days in police custody, though the police officer handling the case characterized Gertrud as a danger to youth.Footnote 131

Finally, Ruth H.'s case also resembles that of Dorothea Naujokat. A Berlin woman arrested on charges of theft in 1937, Naujokat was found not guilty because the court determined that the accusation had been made in error. But because a neighbor had also denounced her as a lesbian, the Gestapo questioned Naujokat and her girlfriend about their sex lives. Dobler indicates that the officer wrote that it perhaps made sense to criminalize lesbianism because it “injures the healthy sentiment of the Volk (das gesunde Volksempfinden).”Footnote 132 This locution calls to mind the so-called “analogy paragraph” of the 1935 penal code—§2—which allowed for the criminalization of anything “which deserves it according to the healthy sentiment of the Volk.”Footnote 133 Although some scholars have asked whether lesbians might have faced persecution under §2, commentary on the law explicitly ruled out such an application and no such cases have been discovered.Footnote 134 As we shall see in the following, the Nazi penal apparatus generally did not punish women who were only accused of having been lesbian, without some other attendant infraction or offense.

In most of these cases, alleged homosexuality did not play a significant role in the punishment the women faced. They had usually come to the attention of authorities because they had committed other offenses that would continue to be criminalized after Nazi rule. Unlike cases such as Waltraud Hock's, where female homosexuality could serve as supporting evidence against someone who was non-Aryan, deemed to be asocial, or had committed political crimes, sexuality seems to have played little-to-no role in these instances. Of course, several of these cases also overlap with other modes of persecution—seduction was thought to have played a role in the cases of Patow, Wally F., and Gertrud R. Especially in the case of Patow, who also faced accusations of prostitution, one can easily see how she could have fallen into the extrajudicial world of the concentration camps. Nonetheless, the fact of these cases remains that the women all received punishments commensurate with the discrete crimes they had allegedly committed. Only in Patow's case, which also involved allegations of seduction, work-shyness, and prostitution, did sexuality influence her sentence. These cases intimate that not all lesbians who fell into the Nazi penal system were persecuted for their sexuality.

This brings us to a fourth mode in the relationship between Nazi officials and perceived lesbians: women who were denounced for homosexuality, but who fell into none of these other categories. These women had committed no crime, were not involved in alleged seduction or clique-building, were Aryan and not deemed asocial, and were not open opponents of the regime. Of five cases that match this description, only Irma Fischer, who married a gay man in 1935 and was tried for fraud as a result, was imprisoned, in her case for three months. She and her husband, Adolf Großkopf, had applied for and received a marriage loan of 700 RM. The court noted that they had hid their “abnormal disposition” from the local doctor in order to qualify for the loan. Adolf, who was an SA man and party member, received two and a half years in prison under §175.Footnote 135

Scholars know of at least four other women whose denunciations as lesbians resulted in no punishment. One of them, Anneliese Wulf, appears in several of Claudia Schoppmann's writings. According Schoppmann, she had a “lesbian identity that would prove immune to the developing ‘Thousand Year Reich.’”Footnote 136 In September 1941, Anneliese—who went by the name Johnny—had been denounced as a lesbian. Although the police investigated, no charges were filed, and she faced no punishment.Footnote 137

In a separate article, I describe the other three such women who were denounced to the Berlin criminal police as lesbians, and who also faced no punishment. One Ursula G. was denounced by her mother in February 1942, after she came across diary entries recording Ursula's relationship with one Margot Scholz. Although the police established (to their satisfaction) that both Margot and Ursula were in a relationship, there were no other circumstances that warranted further intervention. The Berlin state's attorney wrote to Ursula's mother soon thereafter, “Fornication between women cannot, according to the criminal code, be punished … I do not see myself capable of intervening.”Footnote 138 In a similar case Anneliese Klopsch's mother denounced her for allegedly carrying on an affair with one Minna Kehrli. Here too, the Berlin criminal police investigated—deciding that Minna was, in fact, neither a lesbian nor Anneliese's lover—and did not intervene further.Footnote 139

These cases testify to the truth of Hauer's assertion that although “coerced heterosexuality (Zwangsheterosexualität)” characterized the Nazi state, “romantic friendships between women were accepted or at least tolerated, so long as those involved kept their relationships in the private sphere.”Footnote 140 In a similar vein, they point to what I have described as “the duplicity of tolerance.” With this locution, I highlight that groups are only “tolerated” if the majority considers them worthy of opprobrium, oppression, or persecution. Tolerated groups are therefore, using Jacques Derrida's language, subject to a “scrutinized hospitality.”Footnote 141 In that 2017 article, I emphasize how many lesbian women were surveilled or even interrogated for their sexuality—in the same way that the Berlin police observed the women of Lustige Neun—but faced no outright persecution: no imprisonment, torture, murder, loss of work, or even further police interrogation resulted from these cases. Moreover, I argue that the relative openness with which some of these women seem to have lived for years before their denunciations implies a lack of widespread animus against lesbians in Nazi Germany. Thus, although not all lesbians experienced conditions of tolerance, those who did not easily fit into other categories of persecution, and who did not come to the attention of authorities as seducers of young women (or those seduced by older lesbians), could.

Although that conclusion may seem to conflict with any argument that lesbians faced persecution in Nazi Germany, I contended—and continue to maintain—that the two in fact reinforce each other. In this present article, I have sought to illustrate how women who were perceived as lesbians by state actors met with radically different fates depending on their identities, their behaviors, and the circumstances under which they came to official attention. Some women faced intersectional persecution; others faced persecution because bureaucrats believed them to be clique creators or seducers of youth. Still others faced no obvious persecution on account of their sexuality. They were left unmolested precisely because they and their actions were not legible to officials as menacing to Nazism's social and racial projects. Although these varied fates reveal that state actors had no singular concept of lesbianism or its place in Nazi society, they also show that there were certain identities or behaviors that could make women particularly conspicuous as lesbians. These women lived under the duplicitous tolerance of a state that did indeed persecute lesbians.

Conclusions

Examining these cases as a whole, it is easy to see why historians, who have thus far often considered cases alone or in twos and threes, have come to such widely divergent conclusions. Because there was no singular, state-sanctioned persecution of female homosexuals in the same way that there was for male homosexuals, there are simply not as many police and court documents left that describe lesbian life in Nazi Germany or officials’ attitudes toward it. A historian looking only at the case of Ursula G. and Margot Scholz is likely to come to a radically different conclusion than one looking only at the cases of Mary Pünjer and Henny Schermann.

In this article, I have tried to bring these cases together under the umbrella of a more unified model, one that seeks to explain how and why different women met such different fates between 1933 and 1945. Looking at these cases suggests first and foremost that female homosexuality was not a well-defined vector of persecution. That is, there were widely divergent views about the dangers that lesbianism might pose within state and party apparatuses. As a result, individual officers, judges, bureaucrats, and party officials had wide leeway in how they dealt with alleged cases of female homosexuality. As Paisley Currah notes of modern states, “The hope—or fear—that we are governed by a single, rational legal structure is belied by the existence of a virtually uncountable number of state institutions, processes, offices, and political jurisdictions.”Footnote 142 The truth of that observation can be read in these files: there was no one idea of lesbianism that state actors employed to comprehend cases such as those of Hock, Abels, or Ruth H. Each office—indeed, each officer—had its own conception of lesbian identity, of what it meant to be a lesbian, and of what danger that might pose to society.

At the same time, we can identify certain characteristics of different cases that often led women to similar fates. Turning again to Table 1, we can make out trends in how party and state apparatuses treated alleged lesbians accused of similar crimes or identified in similar ways. For some lesbians, other issues and crimes became paramount. Jewish and Black lesbians, along with lesbians who had committed political crimes, often met severe ends, including being sent to concentration camps and murdered. In these cases, their sexuality was sometimes, as Marhoefer argues, a supporting cause of their persecution. In cases of women who committed other crimes unrelated to their sexuality, such as theft, sexuality played little obvious role in their punishment. Courts often sentenced these women to short terms of imprisonment. Finally, women who were denounced as lesbian, and whose cases involved no other legal, political, or racial issues, could usually expect to get off without punishment, albeit after invasive and, we can imagine, unsettling police inquiry.

The cases, in my view, where sexuality became truly paramount, are precisely those in which Nazi officials believed women behaved in ways that threatened Germany's social fabric through clique building and especially the seduction of young women. Although these ideas predated the Nazi period, they were also a common trope of the Nazi persecution of gay men. That is, National Socialists believed male homosexuality was spread through the seduction of youth, which, in turn, made male-dominated organizations such as the SA, the SS, the military, and the party particularly susceptible to homosexual infiltration. They worried that large numbers of gay men concentrated in such organizations could pose a political threat, that they might form conspiracies to destabilize or even overthrow the government.

Because adult women were largely relegated to home and family life in Nazi Germany, though, most ideologues thought lesbianism did not pose an analogous threat. Women enjoyed fewer opportunities for seduction and for clique-building. Nonetheless, the case of Käthe Abels, alongside others in the literature, suggests that when prosecutors and police accused women of behaving in these ways, of seducing young women and of gathering about them cadres of lesbians, they too could face punishment. Indeed, it is no accident that many of the women discussed here were not married and supported themselves through employment—they were already women who did not conform to the gendered expectations of Nazi society. Of course, women like Abels were not typically imprisoned or sent to concentration camps for such offenses. But this pattern suggests that the reasons that Nazis feared male homosexuality could also apply to female homosexuality in certain circumstances. That is, in cases of both male and female homosexuality, officials worried that homosociality risked undermining the fabric of the Nazi Volksgemeinschaft.

Hence, I have sought to illustrate that although lesbians faced discrimination and punishment in unsystematic ways, at least four different patterns of how officials handled these cases become discernible when looking at them in tandem. But the question still looms, that of whether persecution is the correct term with which to describe these patterns of discrimination, punishment, and tolerance. Some scholars insist on rather restricted definitions of persecution, such as Zinn, who limits it to “laws, decrees, or measures initiated by the state or party.” I too have been overly hasty in the past, brushing persecution aside as “systematic harassment … or violence.”Footnote 143 Indeed, the requirement that persecution be unambiguous or systematic is, as Marhoefer notes, one of the chief reasons lesbians have not been granted a memorial at Ravensbrück.Footnote 144 Yet, looking at these thirty cases of women who came to the attention of the Nazi state and party as lesbians, it is hard to deny that they faced something that, however haphazard, looks like persecution.

Reading these cases in tandem thus may suggest that the conception of persecution as systematic or unambiguous appeals to scholars not for ontological reasons, but rather for epistemic ones. That is, such a definition is attractive because it allows the state to come into focus as a cohesive whole, as a unified machinery intent on the suppression or regulation of certain groups and behaviors. It turns the state from a messy collection of actors into an actor in its own right. In contrast, the experiences of lesbians in the Third Reich make clear the need to theorize persecution that is unsystematic, that is an emergent quality of societies and states. I offer heterogeneous persecution as one term that might capture this attribute of oppressions that are not necessarily written in laws or edicts, or expressed systematically across bureaucracies and judicial systems.

These questions and conclusions are not sealed in the past, nor is the need to comprehend such complexities limited to academic historians. These stories have ramifications for how we remember the crimes of Nazism, for how we conceive of sexual identities today, and for how we understand the place of sexual minorities in our own societies. As I noted at the start of this article, at the crux of these questions sits the problem of memorialization, of whether and how to commemorate lesbianism in Nazi Germany.

Of course, memorialization is distinct from history, as historians and public intellectuals have pointed out time and again.Footnote 145 At the same time, decisions of what and how to memorialize are closely tied to the work of analytic history. If there is a problem in the tension between history and memorialization, it is that memorials insist on absolutes; they demand the truth of the matter—certain individuals and groups are cast as either victims or perpetrators, either the persecuted or the persecutors. Historians, of course, are typically reluctant to treat in such inflexible terms. But one of the great imperatives of our time must be to find ways to capture the nuance of analytic history, the desire, as Currah writes, to understand “what might actually be going on,” in the permanence of stone and metal.Footnote 146 To do so, historians must find ways to make themselves amenable to modern populations’ great need for usable history, for a past that can point the way to a better future.

Although I agree with other scholars that rooting identity in oppression poses certain political, ethical, and emotional dangers, I do not believe they are of paramount concern to LGBTQ communities today. Far greater, to my mind, is the danger that the historical oppression of queer people could be forgotten and that, concomitantly, contemporary oppression of queer people might be ignored. To take Judith Butler's words, it is not just a question of historical representation, but also a question of “what makes for a grievable life.”Footnote 147 And so, if we are a society that celebrates sexual minorities and mourns the loss of queer life—as I hope and believe we are—then it not only makes sense, but is rather necessary, to take a fresh look at the question of whether memorials ought to be erected that commemorate lesbian persecution in Nazi Germany.

First, I hope this article makes clear—as I believe was already evident from the existing historiography—that the treatment of male and female homosexuality in Nazi Germany were different phenomena. They obviously rhymed—in particular in the enduring fear of the seduction of youth—but Nazi ideologues and bureaucrats were far more concerned with the gendered implications of homosociality than they were with sexual partner choice per se. Because women occupied a very different place in Nazi society than men, the persecutions of gay men and lesbians were commensurately dissimilar. To be plain: searching for forms of lesbian persecution identical to those that gay men faced is nothing more than a red herring.

Freeing ourselves of the burden constantly to check female experiences against male ones empowers us to see lesbians’ fates afresh. No, there was no pink triangle for lesbians, and no, lesbianism was not criminalized. Nonetheless, the cases explicated here illustrate that lesbian women did suffer. As this article has argued, the heterogeneous persecution of lesbians played out in at least four distinct ways, which included a modicum of tolerance for those women who did not step out of line. But the toleration of some does not throw into question the persecution of others—in fact, it only does so if one insists on seeing persecution and tolerance as mutually exclusive categories. Rather, the complexities of lesbian life in Nazi Germany should allow us to recognize the myriad ways in which persecution and tolerance were constitutive of each other, setting the boundaries of acceptable behavior and identity in the Volksgemeinschaft. Female homosexuality was a contested, fraught, and nebulous field on which fascist anxieties regarding motherhood, eugenic policy, political stability, and social cohesion played out in often counterintuitive and perplexing ways. The work of numerous historians has revealed that lesbians faced acts of silence, taboo, discrimination, and, yes, persecution because of their sexuality. Monuments should reflect it.