How to handle collective actions by workers is an important political issue in China. The state's general antipathy towards organized protest,Footnote 1 coupled with its concern for slowing economic growth, has increasingly led it to respond more forcefully to workers’ collective actions. However, it is a mistake to conclude that local governments in China attempt to suppress all collective actions by workers.Footnote 2 In fact, local governments do not intervene in a large number of such actions and even when they do intervene, suppression is not the only option available to them.Footnote 3 Local governments at times placate workers by actively mediating conflicts between employees and employers in accordance with the labour law.

What explains Chinese local states’ varying modes of response to workers’ collective actions? Existing studies have extensively examined how the size, the degree of organization and the level of disturbance created by workers’ collective actions affect how local governments respond.Footnote 4 In this article, we argue that the types of demands raised by workers is another important factor that determines how governments respond to such incidents.Footnote 5

Data

In this paper, the term workers’ collective action (gongren jiti xingdong 工人集体行动) refers to strikes, workers’ protests, labour activism and demonstrations. The Chinese government unfortunately does not provide official figures on workers’ collective actions. To fill the void, the previous literature has relied on a self-constructed dataset derived from mass media reports about collective action cases.Footnote 6 However, many of these studies do not adequately capture changing labour–state relations. This is because they are not confined to workers’ collective actions but instead encompass various types of mass action.Footnote 7

The frequency of workers’ collective actions, the types of workers’ demands and government responses to these actions vary greatly in relation to specific regional characteristics, including local demographic structure, industrial structure and economic conditions. To minimize biases that may arise from a regionally disproportionate frequency of labour events and other location-specific effects, the current study focuses only on workers’ collective action cases in a single Chinese province, Guangdong.Footnote 8 This area has received a large number of migrant workers and has experienced more collective actions by workers than any other province.Footnote 9

In constructing the dataset, we derived data from the China “Strike map” developed by the China Labour Bulletin.Footnote 10 Our dataset covers collective action cases reported between 2011 and 2016 in Guangdong.Footnote 11 The “Strike map” provides geo-referenced information on workers’ collective actions which is sourced from multiple media reports as well as self-reports on social media. However, it is not a comprehensive or definitive record of all workers’ collective actions in China. Actions that receive little media attention, for example, are likely to be excluded from the dataset. Nevertheless, it is by far the most comprehensive publicly accessible database containing detailed information on workers’ collective actions.

Another limitation of the dataset is that the level of detail available for each incident may differ depending on the information source. To address this issue, we classified the source of each entry in the dataset into one of three categories: thin reports, thick reports from state media and thick reports from non-state media.Footnote 12 Thin reports are self-reports posted on Weibo 微博 or the now-shuttered Wickedonna archives.Footnote 13 Thick news reports provide more detail than thin reports, but how they report government responses may differ depending on the type of media platform used. State media sometimes underreport the level of police intervention or violence; the opposite can be true for reports filed by non-state media.Footnote 14

How Do Local Governments React to Workers’ Collective Actions?

We divided local states’ responses to workers’ collective actions into three categories: non-intervention, forceful intervention and non-forceful intervention. Non-intervention is when local states do not take any practical action towards addressing workers’ collective actions.Footnote 15 This form of response is widely adopted by many local states,Footnote 16 as it helps them to collect information about the level and source of social grievances.Footnote 17

Forceful intervention is aimed primarily at quelling collective actions by workers rather than seeking to resolve them. It does not necessarily imply the use of violence. For example, in many cases police are dispatched but do not take any practical action other than dispersing crowds.Footnote 18 Despite the absence of violence, we still classify this response as a forceful intervention as its main goal is to quell the action.

Non-forceful intervention is a form of response which requires local states to play an active role in resolving conflicts either through mediation (zhengfu tiaojie 政府调解) or negotiation (jiti tanpan 集体谈判). This approach enables local states to settle disputes without having to fully implement the labour laws.Footnote 19 It has also paved the way for the development of party-state-led collective bargaining.Footnote 20 To facilitate this process, Chinese local authorities sometimes dispatch local officials and judges to collective action sites in order to encourage collaborative efforts between labour bureaus, trade unions and courts.Footnote 21

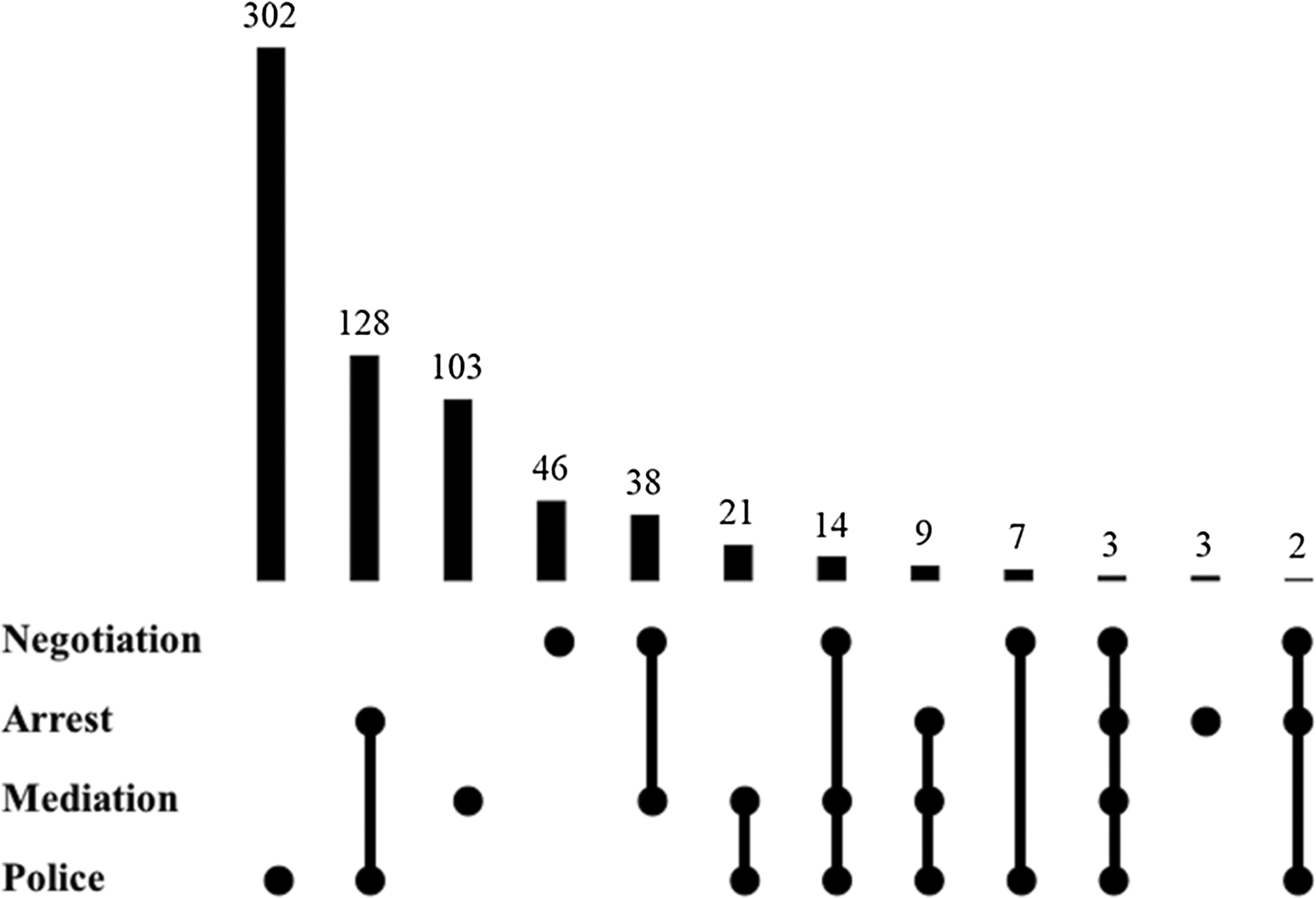

Chinese local governments often employ a combination of different modes of intervention when responding to collective actions by workers. In Figure 1, the dark circles connected by dark lines indicate the simultaneous deployment of multiple modes of intervention. Each of the corresponding vertical bars indicates the frequency of each set of co-occurrences.

Figure 1: Local Governments’ Varying Modes of Intervention in Workers’ Collective Actions

As indicated by the vertical bars, the most frequent type of intervention is police intervention (jingcha chudong 警察出动) that does not also involve any other mode of response (302 cases), followed by police intervention accompanied by arrests (beibu 被捕) (128 cases). This indicates the predominance of forceful intervention in government responses to workers’ collective actions. Interestingly, however, non-forceful intervention characterized a significant portion of government responses: government mediation was used in 103 cases, government-aided negotiation in 46 cases, and mediation accompanying negotiation was used in 38 cases.

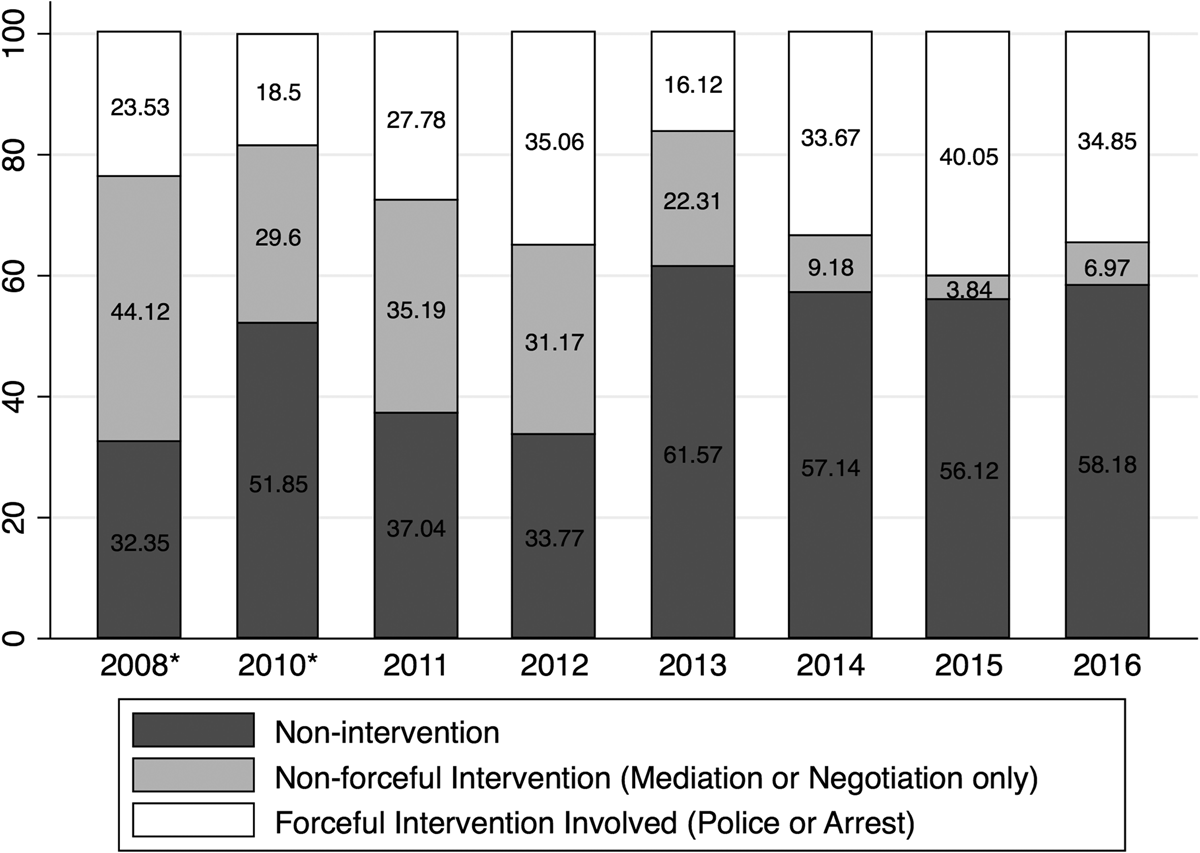

Based on the definitions of non-intervention, forceful intervention and non-forceful intervention discussed above, we created a chart showing the chronological changes in the modes of government response to workers’ collective actions (see Figure 2). As indicated by the dark grey bars, the proportion of cases in which the government did not intervene has grown significantly, especially since 2013, the year in which the Chinese central leadership shifted from the Hu–Wen administration to the Xi administration. This, however, is hardly a sign that the government is loosening its grip on workers’ collective actions. Under the Xi administration, there has been a widespread crackdown on labour NGOs and the pre-emptive repression of worker activists.Footnote 22 This may have reduced the occurrence of collective actions in which local states feel compelled to intervene. The proportion of workers’ collective actions in which states forcefully intervened (indicated by the white bars in Figure 2) has not decreased. The rapid increase in workers’ protests following the 2008 global financial crisis may have led to an increase in the government's reliance on forceful mechanisms.Footnote 23 Our analysis shows that this trend has intensified since Xi's rise to power in 2013. Although some studies argue that there is little evidence of institutional decay in Xi's era, the use of non-forceful intervention mechanisms has declined rapidly, from 44 per cent in 2008 to 7 per cent in 2016.Footnote 24

Figure 2: Government Responses to Workers’ Collective Actions in Guangdong, 2008–2016

Source:

For 2008 and 2010, we used the data from “China strikes.” For other years, we used data from the China Labor Bulletin.

Notes:

The China Labor Bulletin collection only covers the years after 2011, the last year of the Hu–Wen administration. In order to better capture the differences between the Hu–Wen and Xi Jinping administration, we added the data from https://chinastrikes.crowdmap.com (Elfstrom Reference Elfstrom2017). The data only cover the years after 2008. We skipped the year 2009 because the source has thin coverage for that year. The finding from this chart resonates with those of other studies that have found that the Xi administration has adopted different approaches from the Hu–Wen administration in responding to workers’ collective actions. See, e.g., Fu and Distelhorst Reference Fu and Distelhorst2017; Elfstrom Reference Elfstrom2019.

What Do Workers Demand?

We argue that the type of demand raised by workers is an important yet under discussed factor in explaining how governments react to collective actions. Workers’ demands can be classified into three categories: defensive payment demands, defensive social security demands and offensive demands.

Defensive demands are those in which workers lay claim to the minimum benefits stipulated, either strictly or loosely, by the labour laws. Defensive demands can be either defensive payment demands (for example, for unpaid wages, minimum wages or severance compensation) or defensive social security demands (for example, for social insurance provisions). Offensive demands aggressively pursue benefits beyond those which states are legally required to provide – for example, pay increases, an improvement in working conditionsFootnote 25 or worker representation.Footnote 26

Chinese workers, and especially young migrant workers in the coastal areas, have tended to issue defensive demands that are often framed in legal terms.Footnote 27 Only recently have Chinese workers started to make offensive demands.Footnote 28 The continued preponderance of defensive demands in workers’ collective actions reflects the way the Chinese government regulates labour relations through appeals to labour law. Since the early 2000s, the Chinese central government has actively encouraged workers to use the law to defend their rights.Footnote 29 Unlike the old 1994 Labour Law, the 2008 Labour Contract Law (laodong hetongfa 劳动合同法) has made it mandatory for employers to provide all employees with labour contracts. It has also further institutionalized the procedures through which workers may seek redress in disputes with employers over wages.Footnote 30 The promulgation of the labour law, however, has constrained the types of demands that workers can legitimately ask for. The state has attempted to prevent worker grievances from escalating into collective actions by steering aggrieved workers towards individualized court procedures.Footnote 31

However, lax enforcement of the labour law, ineffective court procedures and the nominal worker representation system, which is monopolized by the Chinese official trade union, have often discouraged workers from relying solely on the legal route.Footnote 32 Increasingly, workers have simultaneously sought both formal resolutions in the courts and informal resolutions on the streets.Footnote 33 This explains why many defensive demands are still being raised not just in courts but also in collective actions.

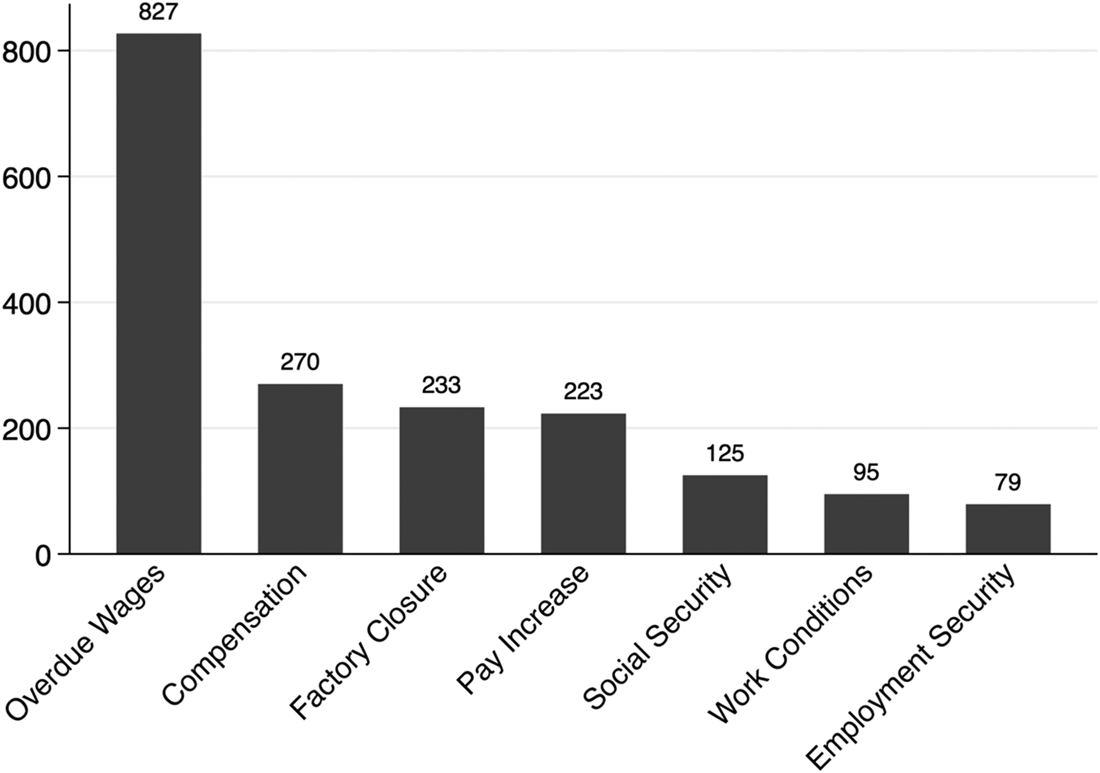

According to our dataset, defensive payment demands are the most frequently raised issue in workers’ collective actions. More than half (55.47 per cent) of the collective actions in the sample contained a demand for payment of overdue wages. Slightly less than one-fifth of collective actions in our sample (18.11 per cent) were motivated by demands for economic compensation (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Top Seven Demands of Workers in Guangdong Strikes, 2011–2016

Notes:

A collective action case can feature multiple demands. For simplicity, we have collapsed overtime regulation issues into the category of demands for improvement in working conditions. Collective actions featuring demands that do not fall into any of the major categories represent only 8.7 per cent of cases in the authors’ sample.

Defensive social security demands (for example, for social insurance payment) are the fifth most frequently occurring type of demand in our sample (see Figure 3). Defensive social security demands differ from defensive payment demands in that they more proactively assert the responsibility of local states to their citizens. This signals an important change in state–labour relations. Chinese workers (especially young migrant workers) have long refrained from asserting their social security rights as they proactively absorbed the market hegemony.Footnote 34

Offensive demands, such as those for pay increases and the improvement of working conditions, are the fourth and sixth most frequently raised demands in our sample. These demands are fundamentally different from defensive demands in that they pursue workers’ interests more aggressively by making claims that go beyond the minimum that local states are legally required to provide.Footnote 35

Workers' Demands, Labour Laws and Local States’ Responses

While all workers’ collective actions are threatening to local states, some are more so than others. The degree of alarm caused by collective actions is largely determined by the kinds of demands made by workers. Some studies suggest that local states consider narrow economic demands less politically daunting and they are therefore more likely to tolerate them.Footnote 36 However, certain economic demands raised during collective actions can still be considered to be “political.” The rise of defensive demands can be politically threatening to local states as they may signal to the central government that those local states lack the ability to regulate labour relations according to the labour laws.Footnote 37 Because they wish to prevent this, local states have a strong incentive to intervene in collective actions featuring defensive demands in either a forceful or non-forceful way. In contrast, there is not such a strong political incentive for local states to intervene in cases featuring offensive demands.

When intervening in workers’ collective actions, local states are concerned with two things: first, they want to minimize the potential of social turbulence as a result of their intervention backfiring; and second, they prefer to settle disputes through the partial and discretionary implementation of the law. This is because the full implementation of the labour laws would discourage firms from investing in the locality.Footnote 38

Despite the effectiveness of forceful intervention in dispersing crowds, local states do not solely rely on it because doing so too frequently can backfire and damage the regime's legitimacy.Footnote 39 Settlement through non-forceful intervention (for example, mediation or negotiation) can reduce the level of social unrest. However, local states cannot easily settle conflicts through the partial and discretionary implementation of labour laws for issues around which there is a high level of legal sophistication. For example, Chinese laws and regulations concerning economic issues such as payment and compensation are highly sophisticated and well established. Moreover, workers themselves are very familiar with these laws and institutions. While local states want to redress issues quietly by directing aggrieved workers to the courts, relying on labour laws to resolve disputes is expensive. Also, after encountering disappointing and ineffective court procedures, many Chinese workers end up taking their demands to the streets.Footnote 40 This makes it difficult for local states to resolve disputes solely based on the court procedures. While they can still settle disputes through mediation or negotiation, the sophistication of the regulations concerning these issues allows little opportunity for local states to settle disputes using non-forceful means. As a result, local governments are more likely to adopt forceful mechanisms when intervening in collective actions featuring defensive payment issues.

Conversely, the nascent laws and regulations concerning social security are less sophisticated and less familiar: the Social Insurance Law, for example, was not passed until 2011. Local authorities have a high level of discretion when deciding the specifics of social insurance provisions, including the contribution rate for employers and workers’ eligibility for social insurance programmes. Ironically, the incomplete development of institutions concerned with defensive social security issues creates room for non-forceful intervention.

Empirical Analysis

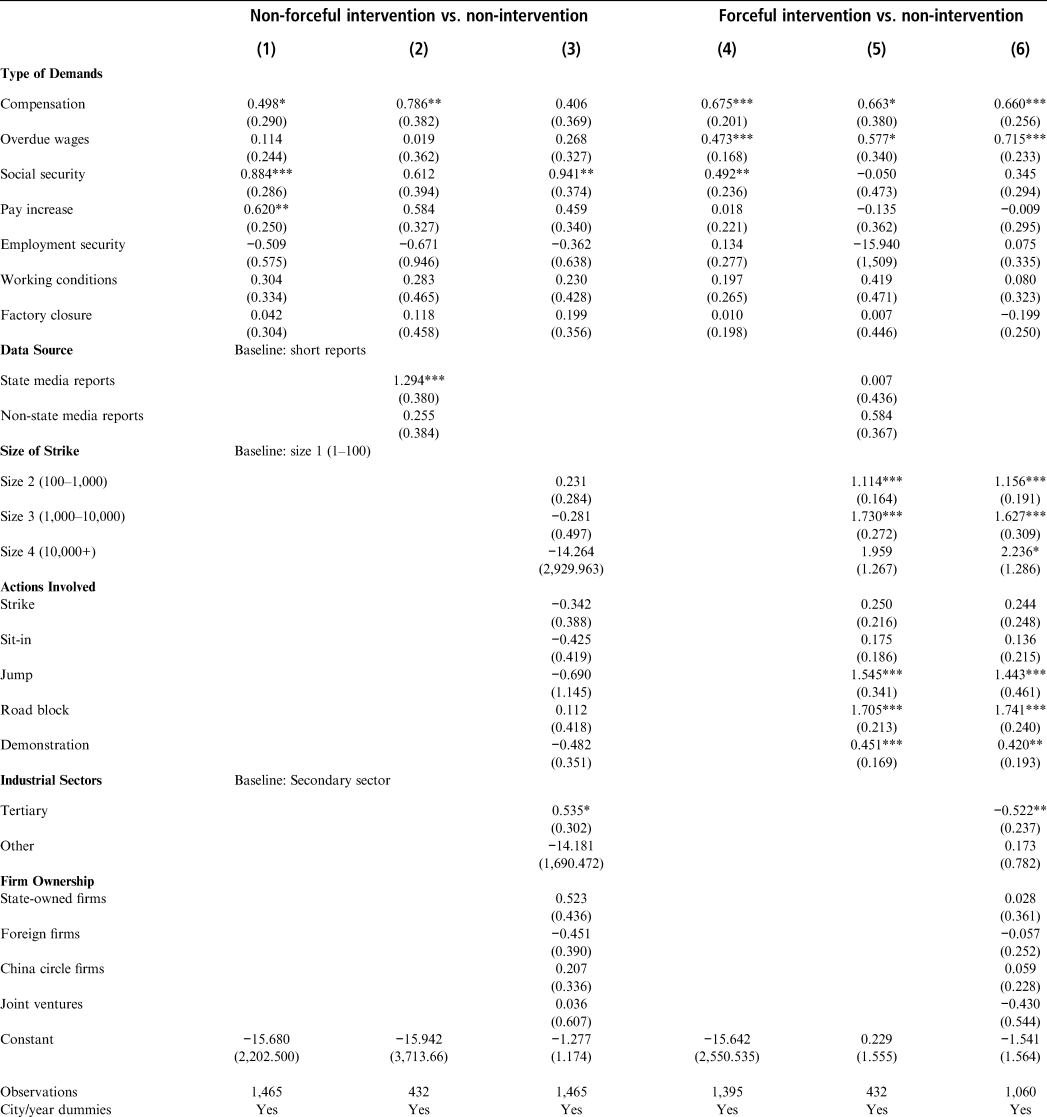

To examine the relationship between workers' demands and government responses, we conducted a multinomial logistic regression analysis. The dependent variables are the three different modes of government responses (non-intervention, non-forceful intervention and forceful intervention) and the independent variables are dummies of the top seven demands found in each of the collective actions in the sample. We also controlled covariates that might affect government responses to workers’ collective actions, including the various sources of information about these actions (added in column 2 and column 5), the size of the strikes, the actions taken by workers during each incident, the type of industry affected, the ownership types of the firms impacted, and the dummies for city and year (added in column 3 and column 6).

Table 1 shows the results of our analysis. The relationship between collective actions featuring defensive social security and non-forceful intervention (as opposed to non-intervention) becomes statistically less significant when the sources of information are controlled (column 2); however, the relationship remains positive and significant in other models (columns 1 and 3). This provides limited yet important evidence supporting our hypothesis.

Table 1: Multinomial Logistic Regression on Government Responses to Workers’ Collective Actions

Notes:

China circle firms indicate Hong Kong, Taiwan or Macau-invested firms. Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The relationship between defensive payment demands and forceful intervention is statistically significant and consistent in our analysis. Collective actions featuring defensive payment demands are more likely to be met with forceful intervention, rather than non-intervention, by local authorities (columns 4, 5 and 6).

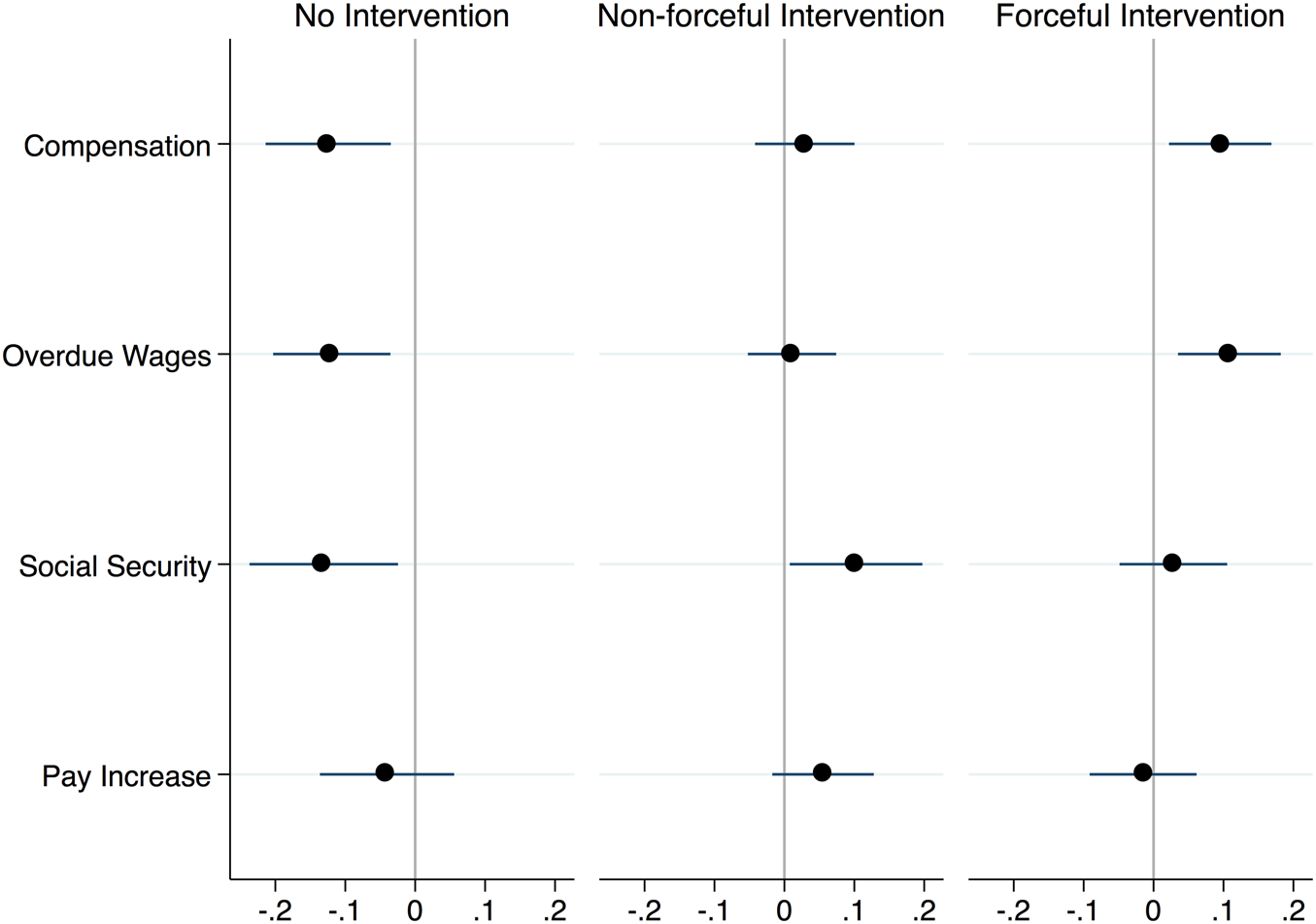

To provide a more intuitive interpretation of the analysis, we created a marginal plot illustrating the marginal effect of the main independent variable (demand type) on the predicted probability of each mode of government intervention.Footnote 41

As Figure 4 shows, collective actions featuring defensive demands (compensation, overdue wages or social security) are more likely to experience intervention. The presence of defensive claims decreases the probability of non-intervention by 8, 7 and 12 percentage points, respectively. The state is also more likely to forcefully intervene when defensive payment demands (for example, for compensation and overdue wages) are present. The presence of the demand for compensation increases the probability of forceful intervention by 4 percentage points, as does the presence of the demand for overdue payment. However, defensive social security demands are more likely to face intervention using non-forceful mechanisms. When social security demands are present, the probability of non-forceful intervention increases by 10 percentage points. Local states are not more likely to intervene in response to offensive demands (such as for pay increases or better working conditions).

Figure 4: Marginal Effects of Different Demands on Local States’ Responses

Our analysis, as reported in Table 1, also finds other interesting patterns. As can be seen in column 2, state media are more likely to report on non-forceful intervention than non-intervention. Column 6 shows how other factors, such as the size of the collective action and the behaviour of protesters, may affect government response. Specifically, the local state is more likely to forcefully intervene in large collective actions. It is also more likely to forcefully intervene in collective actions that involve roadblocks, demonstrations or workers threatening to jump off buildings. The state is more likely to use non-forceful mechanisms to intervene in collective actions from tertiary industries and less likely to intervene in actions effecting these industries using forceful mechanisms. The ownership type of firms, however, does not have a significant impact on government responses. Even when these important factors are considered, however, the correlation between workers’ demands and government responses remains significant. Local states are more likely to forcefully intervene in worker collective actions involving defensive payment demands even when other factors, including the size and type of collective action, the industrial sectors involved and firm ownership, are controlled.

Conclusion

Drawing from a sample of collective actions staged by workers in Guangdong province between 2011 and 2016, this paper finds that the types of demands raised during these actions correlates with local states’ responses. We suggest that the relationship between workers’ demands and labour laws explains why local states respond differently to workers’ collective actions featuring different demands. Local states are more likely to intervene in actions featuring defensive demands (as opposed to offensive demands) as the rise of defensive demands signals the local state's inability to control labour relations through the application of labour laws. Furthermore, states are more likely to forcefully intervene in collective actions featuring defensive payment demands. This is because the legal institutions regulating payment-related issues are highly sophisticated, allowing little room for local states to intervene through mediation or negotiation. In contrast, the comparative lack of sophistication in the laws and institutions that regulate social security creates more room for local states to intervene via mediation or negotiation. Therefore, states are more likely to use non-forceful means when intervening in collective actions in which workers make defensive social security demands.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a travel grant from the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. We are especially grateful for feedback on previous drafts from Mary Gallagher, Feng Chen, Edmund W. Cheng, Yi Kang, Zhongwei Sun, Chris Rhomberg, the panel members and participants at the 2017 Annual MPSA conference, ISA 3rd Forum of Sociology, and the China Reading Group at the University of Michigan, as well as the two anonymous reviewers. We also thank Manfred Elfstrom for sharing his data (China Strikes). Any remaining errors are ours.

Biographical notes

Yujeong YANG is an assistant professor at the State University of New York, Cortland. She obtained her PhD in political science from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Her research interests include labour politics, welfare politics and development strategies in authoritarian countries, with a focus on China.

Wei CHEN is an assistant professor at the School of Government, Nanjing University. She holds a PhD in political science from Hong Kong Baptist University. Her research interests include labour politics, industrial relations and non-governmental organizations in contemporary China.