China has undertaken a process of rapid social transformation since the late 1970s. One of the most significant aspects of this phenomenon is the massive rural-to-urban migration of domestic labourers. Many migrants also bring their children with them when they move to China's largest urban centres. There are an estimated 35 million children from migrant families in China, among them roughly 13.95 million are between 6 and 14 years old,Footnote 1 meaning that they are classified as being of compulsory education age in China.Footnote 2 While potential issues stemming from worker migration and the accompanying hypermobility of school-age children present many types of concerns commonly discussed in the research literature – such as gaps in knowledge, differences in culture, language and identity, concerns about well-being, among other issuesFootnote 3 – the effects of this phenomenon within contemporary Chinese contexts remain understudied and in significant need of further exploration, particularly as it relates to the politics surrounding Chinese education policies.

This article examines policies directly related to the education of migrant children living in and around China's largest urban centres, with a specific focus on those implemented in Beijing. It is here where the education of migrant children is being contested and policy debates over access to education are currently unfolding. This study seeks to 1) examine a series of local regulations put forth by the municipal and district governments of Beijing in response to state policies; and 2) analyse how these education policies develop and reflect the politics of population control at the local level.

Policy implementation, or enactment, is a process that is “far from straightforward and rational and produces a number of social relations, positions, practices and performances.”Footnote 4 Previous studies have examined the development of both state and local policies in China with regard to issues of educating migrant children in urban cities.Footnote 5 This existing research literature largely discusses education policies as regulating the actions or practices of different stakeholders or institutions that deal with the education of migrant children and addresses the role of established power structures, including the mechanisms through which they operate both within and across social fields. However, studies have yet to examine how these policies function to transform the identities of rural migrants and their children – creating new subjectivities and spatial identities through forms of disciplining, monitoring and controlling individuals at both state and local policy levels.

With the intention of building upon and bringing transnational perspectives into ongoing discussions surrounding both the conception and purposes of “policy sociology,”Footnote 6 this article emphasizes two important aspects that previous studies of China's education policies have tended to underplay given their focus on socio-economic factors. The first argument is that education policies have an underlying agenda that extends beyond that of simply addressing the educational needs of migrant children – as such, this article seeks to highlight the discursive functions of policy texts. The second argument is related and seeks to raise the question: for whom are these policies intended, and who is best served by them? As such, this study extends current research by exploring the discursive functioning of education policies, bringing into consideration community perspectives regarding policy enactment, in addition to addressing how policies come to shape collective understandings both of what is possible and what becomes constructed as outside of the realm of possibility.

Policy Enactment in Strong State Contexts: Weakening Responsibilities and Strengthening State Control

Policies are not the work of a single author but rather represent a confluence of interests amalgamated through processes of strategic compromise. Policies can be critically analysed in terms of how they are taken up and normalized through the disciplining of both individual and collective actions and thinking – in essence framing what are considered to be common-sense ways of navigating structural conditions established in part by those in positions of authority. Policy analysis thus needs to consider how social practices are reflected and created, in addition to analysing “the values, feelings, or beliefs they express, and on the processes by which those meanings are communicated to and ‘read’ by various audiences.”Footnote 7

It is common for researchers to focus on the regulatory functions of education policies. And it is along such lines that policy analyses often mainly consider the aims of policies and their success or failure to address defined and determined problems. Yet, policies comprise more than just their anticipated regulatory functions and should be recognized as more than just texts.Footnote 8 It is in this regard that education policies, such as pieces of legislation or formalized national strategies, represent “discursive processes that are complexly configured, contextually mediated and institutionally rendered.”Footnote 9 Central to this understanding of education policies is the recognition that policies are not simply implemented – rather, they are enacted by various stakeholders and function in dialogue with existing social values, commitments and forms of experience. Thus, policies are subjected to different interpretations not only within institutions and institutional structures but also in ways that are limited by the possibilities of discourse.

The policy enactment process is interpreted through social, emotional and cultural lenses leading to their construction in practice. Key here is the notion that attention to the discursive functioning of policies highlights “the multifaceted ways in which policies are read alongside/against contextual factors, by different sets of policy interpreters, translators and critics.”Footnote 10 It can be argued that policies operate discursively while simultaneously being situated within dominant discourses. The idea of a dominant discourse, as Foucault explains, is a functioning similar to that of a broad conceptual lens through which epistemological and ontological operations are disciplined via their participation in different forms of disciplinary power.Footnote 11 Foucault's interests concern how discourses are constructed, reconstituted and evolve over time, as well as how discourses frame and shape everyday existence, in part through the various means by which they “form the objects of which they speak.”Footnote 12

A number of research studies have examined the politics of urbanization and the impact of coercive state power occurring under contemporary neoliberal regimes on education reforms.Footnote 13 While these and other studies point to the broader implications of education policies, much of this body of research is situated within Western contexts. There are some exceptions with studies that have addressed how forms of neoliberal governance have developed in the strong state contexts of certain Asian nations, including China.Footnote 14 Aspects of this research help to highlight some of the tensions embedded within education reform policies wherein state responsibilities are weakened at the same time that forms of state control are strengthened.

In practice, this has meant an ongoing process of decentralizing responsibilities associated with the provision of public education and doing so in the name of establishing increased flexibilities and increased local governance. In urban Chinese contexts this shift has coincided with an intensified and consolidated focus on initiating means by which to enforce greater degrees of population control. “On one hand, decentralization has been the focus in the recent educational reform, but on the other, functional centralization by unifying strengthening governance and management at various levels of government has also been enforced.”Footnote 15 In the context of this study, education policies reflect in part a re-inculcation of existing state bureaucracies in addition to the reframing of discourses surrounding the consequences of large-scale domestic migration. Herein the semi-paternalistic role of the state becomes ensconced in the rhetoric of guaranteeing that it is “taking care” of the people, while simultaneously attempting to ensure this occurs under conditions continuing to advance state hegemony.

This paper focuses on the city of Beijing. As China's capital city, Beijing serves as the nation's political centre. Situating this study within this context offers a unique opportunity in terms of conducting research on education policies given the relations between local and central state governments and various policy actors. In certain regards Beijing can thought of as the frontline for analysing emerging trends that will subsequently come to have an effect across the entire country. Given that Beijing offers a unique context for understanding trends in education policy while at the same time serving as a bellwether for larger policy trends, the decision to focus on Beijing for this study is justified insofar as it seeks both to highlight specifics related to the socio-political contexts of Beijing while simultaneously offering theoretical contributions, intended to offer broader application, that exist in dialogue with similarly focused research addressing the development of education policies in other cities. Moreover, other scholars’ policy analyses and reports about different cities, including Shanghai and other provincial capital cities, inform and contextualize our argument related to policy enactments targeting the education of migrant children as a form of population control in China's urban centres.Footnote 16

Research Method

This article is based on longitudinal qualitative research conducted in Beijing. Data was collected during visits to various migrant settlements in the city, focusing on five communities across six districts in Beijing.Footnote 17 One author of the present study (Min Yu) initially conducted a 14-month ethnographic study in these five migrant communities from 2010 to 2011 and subsequently followed up with participants from the initial study for extended interviews and multiple re-visits during 2014 and 2016. Group interviews were conducted with migrant teachers and parents in schools, community centres and other public places, then 15 migrant teachers and parents were selected from different migrant settlements for multiple in-depth interviews. Participant observations in schools, community meetings and other public gatherings, such as public meetings with district officials, were also conducted.

The primary data for this specific article includes a variety of policy documents related to the education of migrant children. This collection of data is complemented by information derived from interviews with teachers, parents, community members and non-governmental organization activists concerning school closings, community demolition and migrant student relocation. These are further supplemented by field notes collected from participant observations occurring in migrant communities and during public meetings with district officials.

The perspectives captured in the data represent those of migrants who moved to Beijing from different regions across China, have stayed for different periods of time, worked various jobs in different districts, and have children of different ages and genders. Additionally, nine activists and researchers were interviewed, who have been working closely with different migrant children schools and are affiliated with various governmental or non-governmental organizations which have established programmes across different migrant communities. The interviews and observation data are presented through summaries of participants’ individual narratives and collective voices.Footnote 18

The Early Development of Migrant Children Education

The struggles over educating migrant children in urban China in many ways stem from policies associated with the Chinese household registration system (hukou 户口).Footnote 19 The migrant population is commonly considered to be both out of place and out of control because migrants do not remain in the place where they hold their hukou.Footnote 20 Given the extraordinarily large size of this demographic group, it presents stressors upon established modes of state control that are largely based on a degree of presumed stability in which populations remain fixed in space. Government officials view the provision of services to migrants as a drain on urban public resources. Issues related to the social and educational needs of migrant children emerged soon after migrant families started to move into major cities in the 1980s. However, it was not until 1996 that the Chinese central government drafted specific regulations concerning schooling issues for migrant children.Footnote 21 Consequently, it has largely been left to local governments to “experiment with different ways of providing education for migrant children.”Footnote 22 The challenges connected to educating children from migrant families, who are often referred to as migrant children, highlight complexities stemming from an absence in government responsibility.

It was the same absence of official state regulations that both created opportunities for migrants to develop their own social and economic niches within cities and spurred them into action. The formation of migrant worker organizations and coalitions was a direct response to the absence of meaningful state regulation and social welfare programmes in certain areas, such as migrant settlements in the cities. In response to concerns about the education of children from migrant families, migrant children schools – first established by parents within the migrant settlements in the early 1990s – emerged in several large cities in China to serve children from low-income migrant families.Footnote 23 These schools are also often known as “unofficial” schools because many are unregistered and thus have no officially recognized status. For many years, these schools have remained the primary education providers for migrant children.

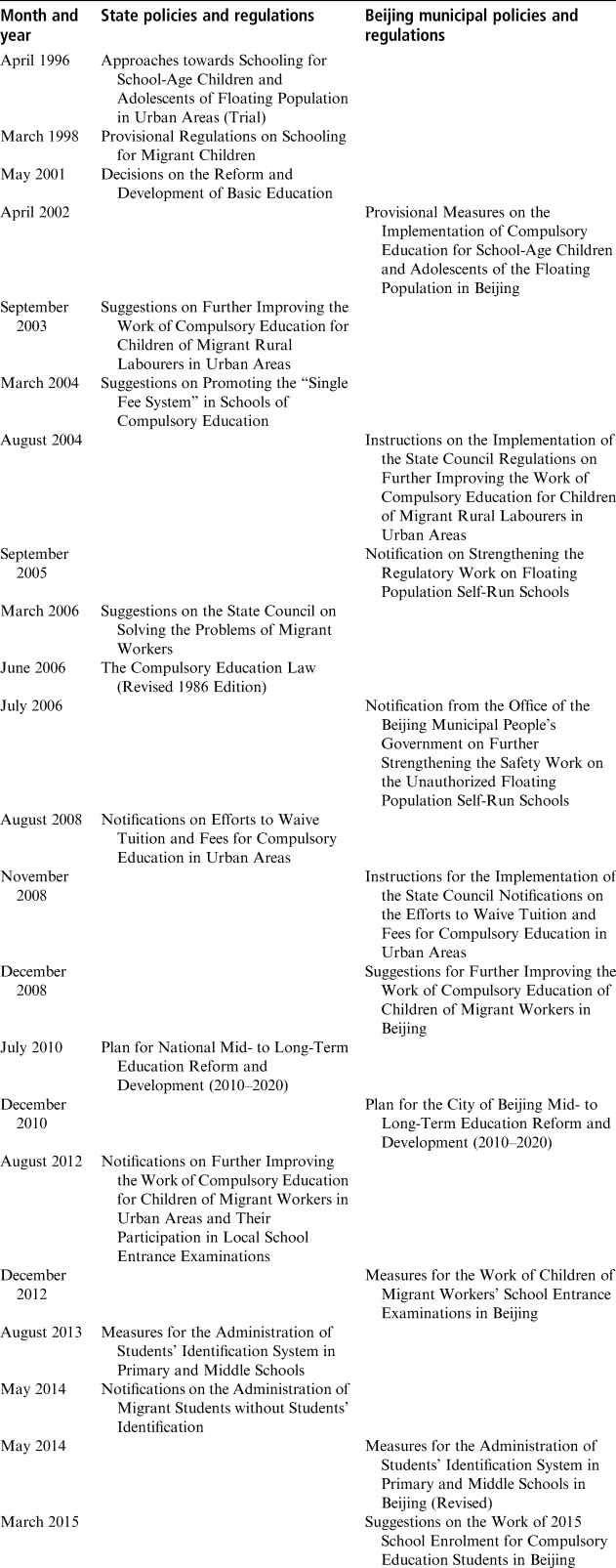

After a decade of letting unofficial migrant children schools serve as the primary education providers for the majority of migrant children, the Beijing municipal government responded to the 2001 central state regulation with its own policy, published in April 2002 (see Table 1). This policy acknowledged that “social forces organized schools to accept migrant children and adolescents in the areas of floating population concentration” (Articles 9 and 10). By that time, migrant children schools in Beijing had begun to flourish, and the number of migrant children schools in different migrant settlements across the city had reached several hundred.

Table 1: State and Beijing Municipal Education Policies Concerning Migrant Children

Sources:

Compiled from various government documents relating to migrant children education, hukou administration, xueji administration, etc.

It was around this time, roughly between 2002 and 2003, when the Education Committee of a number of different districts started to issue official permissions to migrant children schools.

Yet, there were no publicly available standards to reference at the time and the process was essentially relegated to local school district officials to determine which migrant children schools would receive permission to operate officially. Many of the schools that applied for permission to be recognized as an official, district-sanctioned school received different and often contradictory statements from district officials. Only a very small number of schools succeeded in obtaining an official permission.

Approximately 60 migrant children schools were granted official permission to operate (banxue xukezheng 办学许可证). Many other migrant children schools received a different written approval (pizhun banxue 批准办学), an approval given by the District Education Committee as an alternative to operate a school. District officials did not provide clarification regarding the difference between a permission and an approval in the application process. In fact, the approvals did not prevent migrant children schools from being closed by local government. Needless to say, the challenges and struggles related to providing access to education are particularly true for migrant communities, given the complex social and political environments.

It is worth noting – as many scholars in China studies have documented – that the so-called late socialist or post-socialist states did not radically break from the past or simply retreat from positions of power.Footnote 24 Instead, a reconfiguration of socialist rationalities and practices created new problems and forms of inequality. In the case of regulating migrant communities and migrant worker organizations in urban China, when authorities decide to reclaim control over these new and evolving social spaces, government officials are in a position to achieve set goals despite resistance from those engaged in forms of community action.Footnote 25

The Enactments and Functions of Policies for Migrant Children Education

There are arguably two stages in the development of centralized education policies and regulations targeting migrant children's schooling.Footnote 26 The first was a stage of vague governmental responsibility, characterized by three central state government policy regulations issued in 1996, 1998 and 2001. These policies encompass the central state government's basic policy framework for the compulsory education of migrant children between 1996 and 2003. Specifically, the 1998 regulation proposed what came to be known as the “Two Mains” (liangweizhu 两为主) framework – stating that migrant children in host cities could mainly attend the local public schools and that the host cities should take the main responsibility for managing issues related to schooling for migrant children. Although this framework placed the onus of responsibility on local governments, those in positions of power seemed reluctant to address the issue of educating migrant children, perhaps in large part because educational funding continued to be tied to the hukou system.

Given mounting pressure and the need to address issues that might otherwise be construed as a large-scale educational crisis, some local governments were compelled to draft their own regulations in direct response to policies crafted by the central state government. As mentioned above, the first municipal regulation regarding different aspects of educating migrant children in Beijing was published in 2002. This regulation listed specific conditions under which migrant children could apply to attend a public school, albeit on a temporary basis (Articles 6 and 7), such as the particular documentation that would be needed and the requirements that would need to be fulfilled. However, the main focus was to urge migrant parents to send their children back to their hometowns where they hold their hukou (Articles 1 and 4).

The second stage of re-emphasizing governmental control can be thought of as primarily characterized by central state government regulations issued after 2003. Despite the emphasis on the need for local governments to play a primary role in monitoring issues and administering procedures related to the education of migrant children, these regulations did not stipulate how the local governments should work to enact these policies. There remained a rather significant discrepancy between the stated aims of the central government's policies and local governments’ responsibilities concerning the education of migrant children. Local governments were afforded a certain degree of latitude regarding how to interpret and adopt these regulations – including methods for initiating processes of allocating resources at different institutional levels.

Without clearly defined policies outlining the specific responsibilities of local governments at the provincial, city and district levels, what often happened during the policy implementation processes could perhaps be best captured by the statement: “where there is a policy, there is the countermeasure.”Footnote 27 The trends associated with the later stage of policy developments affecting migrant children schools – also referred to as the stage of re-emphasizing government control – reflected central state policies that placed greater restrictions on community-based organizing and the education of migrant children.Footnote 28 As for the city of Beijing specifically, the response to central state policies was perhaps most clearly evident in the introduction of the requirement of five certificates (wuzheng 五证) and the implementation of the national student identification system (xueji 学籍), and their impact on community-based organizing and relocating migrant students at the local level.

Five certificates

One of the most significant mandates put in place by the Beijing municipal government during this period was the introduction of the five-certificates policy which stipulated specific documentation as a prerequisite for migrant children's access to compulsory education in the city. In response to the 2003 state government regulation, the Beijing Municipal Education Commission issued a new regulation in August 2004. This regulation developed the procedural requirements for parents or legal guardians of migrant children applying to attend public schools in Beijing on a temporary basis through the city's neighbourhood government official units. The policy – widely referred to as the “five certificates” – refers to the following categories of documents required for migrant children to have access to local public education: a Beijing Temporary Living Permit; a Certified Proof of Address (official rental contract or proof of home ownership); a Certified Labour Contract (official payroll verification or official business operator's permit); a Certificate of No Potential Familial Guardian Residing in the Place of Origin, which must be issued by the local township-level governments of the place of origin; and a Registry of the Entire Family's Household Permanent Residency.

In addition to the official and unofficial fees required to obtain this documentation, the five-certificates policy has largely come to represent yet another substantial legal barrier for the majority of migrant parents to move forward in the process of being able to educate their children in state-supported schools, albeit only on a temporary basis. The underlying implication of this requirement is that children without a Beijing permanent residency should return to their place of origin, where they have hukou, in order to have access to compulsory education. In practice, it is tremendously challenging for migrant parents to collect all of these certificates in a reasonably short period of time. For instance, many migrant workers do not have stable employment, so a Certified Labour Contract is difficult if not impossible to obtain. As for the Certificate of No Potential Familial Guardian Residing in the Place of Origin, the process of collecting all the associated paperwork involves multiple trips back and forth between the city and the countryside. Migrant parents have to bear all the costs – in terms of both time and money, as well as the potential danger of losing their temporary jobs by taking leave – associated with returning to their places of origin. Moreover, undertaking the journey back to one's place of origin does not guarantee that a person will be able to obtain a certificate from the local government. Failing to provide the required certificates in a timely manner was, in turn, interpreted as a reason to blame migrant parents for failing to enrol their children in public schools even though the “door” to public education was supposedly “wide open.”

Starting in 2014, Beijing put forward a new regulation known as the “five-certificates consolidation.” This stated that only when the entire family's place of residence and the parents’ workplaces were in the same district could a child apply to attend school in the district. Different districts and individual schools subsequently sought to reinterpret and extend municipal-level regulations by setting their own specific requirements regarding school admission for migrant children, such as adding social security payment records and other new requirements and requiring as many as 28 documents or certificates for the initial screening.Footnote 29 Moreover, having to provide as many as 28 different documents only qualifies migrant families to submit an application to attend a public school. Many school districts and public schools also elect to conduct home visits and interview migrant children as a prerequisite for admission. Ultimately, even in instances where migrant parents provide all required documents and pass the initial screening, access to public schooling is not guaranteed, given that the entire application could be rejected by the school if the home visit or the interview are regarded as unsatisfactory.

In sum, the five-certificates requirements have changed over time, with demands intensifying significantly in recent years. Furthermore, when the national student identification system was introduced, a policy originally intended to facilitate greater ease in processes related to student transfers and registration, local governments leveraged this in ways that allowed public schools to continue to reject migrant children's admission and enrolment.Footnote 30

National student identification system

China's Ministry of Education first introduced a unified student identification system in 2013.Footnote 31 Following a year-long trial period, the student identification system, or xueji, was formally implemented nationwide.Footnote 32 Its purpose was to ensure that each student receives only one unique 16-digit ID number, in order to better track all students. This student ID number would thus follow the student throughout his or her entire education – from elementary through post-secondary education. This student ID system was initially touted as a means by which to simplify the process of tracking a student's academic record and education history, not to serve as a way to determine school enrolment or function as a prerequisite for admission to public school. However, this new system posed a unique problem for migrant children who attend unofficial migrant children schools. Students in these schools are not provided an academic record that can be linked to their ID number because migrant children schools are not officially recognized by the Chinese Ministry of Education. Without this, even if a migrant student's family was able to collect all required certificates, he or she could no longer transfer into a public school after having attended a migrant children school without official status.Footnote 33

In certain instances, students, who had been enrolled in a migrant children school that obtained an official permission to operate from the Education Commission, were not allowed to re-enrol in the same school if they lacked the required documentation associated with the five-certificates policy and thus could not obtain an official academic record linked to their student ID number. Even if these schools were willing to accept migrant students regardless of their document status, they would not be allowed to register these students or assign them student ID numbers. If a school did attempt to do so, it would likely face the risk of incurring severe punishments from the district government, including the possibility of having their permission revoked.

As of May 2016, there were roughly 112 migrant children schools in Beijing, serving over 65,000 migrant children.Footnote 34 For these children and their parents, the creation of the national student identification system presents another more complex problem to navigate. It places migrant families in a situation where they are presented with a choice of three possible decisions to make regarding the education of their child/children: 1) have their child/children continue to attend an unofficial migrant children school, thus risking having to address further issues in the future; 2) leave their jobs/opportunities in the city – the reason why they migrated in the first place – and move the entire family back to the place of origin where their household registry is located in order for the child/children to participate in the national identification system; or 3) send their child/children back to the family's place of origin alone and become part of an increasingly large number of “left-behind children” in China's rural areas. Regardless of the choice migrant families make, the reality is that the living and schooling experience of thousands of migrant families and children has been drastically affected by the creation of the national student identification system.

Constraining migrant children schools

Restricting and inhibiting the further development of self-run migrant children schools has also been an area of significant focus for the Chinese government and its administrative agenda in recent years. For instance, the 2005 Beijing Regulation that specifically focused on regulating migrant children schools put forth guidelines related to strengthening and more clearly outlining regulations affecting these schools.

The guidelines are commonly referred to as a policy that “diverge some; regulate some; and obstruct some” (fenliu yipi, guifan yipi, qudi yipi 分流一批, 规范一批, 取缔一批). In practice, district governments opted to emphasize processes for cracking down on migrant children schools as the correct interpretation of this regulation. Not only did all districts stop accepting applications or issuing permits for migrant children schools to operate as soon as the 2005 regulation was published, they also began shutting down many of these schools – along with other grassroots organizations aiming to provide social services to those living in Beijing's migrant communities. For example, 239 migrant children schools across multiple districts were shut down during the summer of 2006, displacing over 100,000 migrant students. Even though the official statement was that these schools failed to meet the school operating standards, it is worth noting that this mass closure of migrant schools in Beijing coincided with increasing anticipation surrounding the upcoming 2008 Olympics. Perhaps somewhat ironically, the creation of the Standards for Running Primary and Secondary Schools in Beijing by the municipal-level government did not occur until December of that year, almost six months after these arguably low-performing schools had already been shut down.Footnote 35

According to the 2006 statement issued by the Beijing Municipal Education Commission leading up to the initial round of school closures, all districts and county governments should follow the “three first and three later” (san xian san hou 三先三后) principle. That is to say, municipalities attempting to address perceived issues with domestic migration should begin by 1) relocating migrant families before demolishing the residential homes where they had lived; 2) making plans to actively support the process of transitioning migrant children into local public schools; and 3) establishing clearly demonstrated pathways for integrating the children of migrant workers into the local public schools. Then, only after completing these first three tasks should the municipality begin to 1) close migrant children schools; 2) implement an organized process for enacting the pre-planned approach for relocating students who had been attending migrant children schools to local public schools; and 3) demolish the now vacant buildings that had functioned as migrant children schools. However, the implementation of various regulations and policies often prioritized processes that aimed to outlaw and close schools, as opposed to taking more systematic and substantive approaches towards integrating students from migrant children schools into local public schools. The reality of the socio-political governmental undertaking associated with the enactment of the “three first and three later” policy principle, insofar as the multilevel relocation process was concerned, in practice became a matter of what most parents described succinctly as “you are on your own.”

This experience was perhaps most evident in terms of how a series of large-scale crackdowns on migrant children schools unfolded. In 2006 a series of informational meetings were held prior to the closure of over two-hundred migrant children schools, but such efforts fell well short in terms of actualizing the claimed goals of the “three first and three later” principle. In 2011, another large-scale series of forceful shutdowns occurred wherein numerous migrant children schools were completely demolished overnight.Footnote 36 Compared to the previous shutdowns in 2006, when several public hearings were held, the 2011 round of school closures was more abrupt, with all levels of government, from municipal to district to township, firmly declaring that the unofficial schools serving migrant communities would be closed without any further debate. Despite promises to migrants from the Municipal Education Commission and district committees that public schools would welcome migrant children unconditionally and that no students would lose access to formal education, numerous children were displaced and left without official or unofficial local schooling options.Footnote 37 To be clear, the actual consequences of these policies meant that the majority of students attending these migrant children schools not only lost access to the schooling they had been receiving but also did not gain access to public schools. It is important to note that the lack of proper arrangements and insufficient support for the systematic relocation of students did not halt the demolition of migrant children schools.

Relocating migrant students

To further examine the challenges migrant children and their parents face during relocation and the subsequent conflicts that have emerged, it is crucial to pay attention to the two types of local school relocation processes. One is the process of enrolling in local township public schools; the other is the alternative approach of relocating students to the government-subsidized privately run schools (minban gongzhu xuexiao 民办公助学校). During one interview by the authors with migrant parents and activists who closely worked with migrant communities, the narratives collected from community members proved quite different from what was described in the official government data and reports.

Regarding local public schools, the major concerns for migrant children and their parents remain the bureaucratic requirements, namely the five-certificates policy and the national student identification system after its establishment in 2014. Additionally, many local public schools established their own unique rules and requirements especially for migrant children attempting to enrol. One of these rules is that migrant students who obtained the five certificates must then take the school-entrance examinations, and only those who score above a given threshold are able to enrol. Furthermore, many public schools have also developed various justifications – such as “seat shortages” – to ask migrant parents for a “voluntary” sponsor fee.

Some migrant families could still find themselves in a situation where they are not able to have their children attend the public school that they had been promised they could enter. For example, in over half of the public schools in the six districts where aspects of this research study were conducted, branch schools were created specifically for migrant children. These types of branch campus schools are often located in recently converted facilities and separated from the original schools with which they remain associated in name only. They are late additions to the public-school system, sometimes appearing just before the beginning of the school year. Again, for the migrant parents and families who were able to successfully navigate and complete the requirements, more often than not they are late to discover that their children are attending a branch campus school in addition to learning that the facilities are not comparable – with the branch campus schools seeming to be less resourced than their public-school counterparts. As some parents described in interviews, they were startled to learn that some of the branch campus schools did not have enough desks or chairs for the children, or that the facilities appeared to still be under construction with building materials scattered about the school or playground. Needless to say, there was a certain degree of frustration expressed as some parents and family members believed the migrant children schools that had been demolished for “safety reasons” were in better shape than some of the new branch campus schools their children were expected to attend.

The second type of school receiving migrant children is the government-subsidized privately run school. These schools are the main types of schools designed to support the relocation of migrant children to public schools. Most are technically private schools that also receive subsidies from the government.Footnote 38 Furthermore, a large number of these schools had previously been migrant children schools – having received official permission from the government to continue to operate and not forced to close. Many of these former migrant children schools were sought out by local district government specifically for the purpose of enrolling migrant students from other closing schools. One of the most significant differences between these government-subsidized privately run schools and other migrant children schools is that they are entitled to receive government-subsidized educational funds, as well as use public facilities in certain instances. The subsidized private schools are not significantly different from many of the now demolished migrant children schools, in terms of curriculum design, classroom structure and even the majority of the teachers. Similar to how some of the branch public schools mentioned above were set up seemingly overnight, some of the newly converted government-subsidized privately run schools were also not well prepared to receive an influx of migrant students. Issues such as oversized classes, insufficient classroom spaces and limited school supplies, shortage of teachers, and so forth are common. Somewhat ironically, these same types of issues were among the primary criticisms levied against migrant children schools and led to their closure and subsequent demolition in numerous instances.

Furthermore, the official statements published by different districts and municipal governments use different terms to describe these private schools, leading to confusion and perhaps misleading the public in certain respects as well. Some referred to the schools as “legal schools,” while others claimed that all government-subsidized schools are “public schools.” Moreover, if these schools are truly to be regarded as public schools, then no family should have to pay a tuition fee, as is required by the 2008 State Regulation. Yet in spite of this, what became quickly apparent for migrant families was that the students being relocated to these schools continued to pay tuition fees for each semester that they remained enrolled in the schools. Some subsidized private schools might selectively overlook the absence of certain certificates but then apply an additional ongoing fee or surcharge to the tuition fee they were supposedly prohibited from charging families in the first place, meaning that the tuition rate was applied flexibly based upon the number of certificates they were able to obtain.

It is crucial to recognize that these schools share many similar issues with the migrant children schools that were demolished: the administrators of the schools mainly use private funds to run the schools, they recruit and employ migrant teachers, and the students mainly come from migrant families. Even though it is beyond the scope of this paper to address both why and how these schools were originally presented as a better alternative than migrant children schools and thereby deemed a more appropriate solution in terms of providing migrant children schooling, future studies might examine how these schools function as well as the complexities surrounding the purposes of these schools. And lastly, more critical research is needed in order to understand the types of strategic compromises that occurred in order for these schools to emerge as a legitimized temporary strategy for addressing issues related to the education of migrant children.

The Discursive Politics of Population Control

In a recent policy report, Liang and Song discuss different frameworks guiding the central government's education policies concerning the education of migrant children in host cities.Footnote 39 The frameworks were developed from what is colloquially known as the “Two Mains” (liangweizhu 两为主). As discussed above, the Two Mains refer to who ought to assume the primary responsibility for educating migrant children, asserting that this should mainly be the work of public schools and that it should mainly be overseen by the local governments of host cities. This policy framework was later modified and expanded in certain ways, becoming known as the “Two Includes” (liangnaru 两纳入) – referring to an assumption that plans related to the education of migrant children ought to be included within urban development plans and that this work should also be included within the scope of local government fiscal planning. It was then later adapted further into a policy framework referred to as the “Two Unifies” (liangtongyi 两统一) – focusing on 1) unifying education services for migrant children based on living permits in the host cities; and 2) unifying financial transfer programmes in order to allow education exemptions, subsidies and per-pupil funding to be more easily allocated to host cities.

Implied within the evolution of these policy frameworks is a suggestion that these trends reflect an improvement in the education of migrant children, simply by allowing them the opportunity to enrol in the public schools of their host cities. And on a surface level this would appear to be the case, given the creation of procedures detailing what conditions need to be met and which materials are required for admittance to public schools. However, local governments have, in fact, been expressing scepticism openly towards the effectiveness of these frameworks. Some urban development plans for large cities such as Beijing contain contradictory statements and procedures which discourage the actual implementation of these policies.Footnote 40

To reiterate, these policy developments represented both the continuation and extension of policies seeking to control the floating population. Beijing has continued to introduce a series of policies starting in 2010 aimed at more strictly limiting the possibilities for migrants without local urban household registry to exercise the same discretion over aspects of their lives, such as being prohibited from purchasing cars or homes in the city. In terms of educational issues, which includes establishing the possibility for young children to have access to public education, policies have demonstrated themselves to have followed an even more conservative direction.

Indeed, this conservatizing shift has even been expressed publicly by government officials – an occurrence that is perhaps more of an exception than a norm with regard to policy implementation. The former director of the Beijing Municipal Education Commission used the metaphor of the “lowland effect” (wadi xiaoying 洼地效应) to describe the perceived necessity for inhibiting open access to education for migrant children in ways similar to building the infrastructure necessary to control water from inundating a floodplain:

the problems of migrant children in Beijing are no longer merely educational problems, they are first urban administration issues. What is the capacity of Beijing? How many migrant workers and children can we accept? If there is no limit, there would form a “lowland effect,” just like the water tends to flow to lower land: if we make our better education free, then more and more people will come.Footnote 41

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that good schools located in better-performing school districts have never truly provided open access to all urban residents living in other parts of the cities, to say nothing about the presence of migrant children and their educational needs.

Discussion: Discursive Functions of Education Policy

The case of Beijing's migrant children education highlights important but frequently overlooked aspects related to the impact of education policies. On the surface, the regulatory aims and mechanisms of certain policies have affected migrant children schools, the students who attend them, and the migrant families and communities who rely upon these schools. Less obvious are the nuances related to the broader impact of these policies insofar as they simultaneously function discursively in order to frame collective notions of common sense regarding the education of migrant children.

As the capital of China and one of its largest cities, Beijing has undergone both significant and continuous urban expansion while simultaneously devoting significant resources and attention to promoting a positive image of the city. Despite their contributions, migrants are not widely viewed as being helpful in terms of improving the image, status or appearance of Beijing. Crackdowns on migrant communities and migrant children schools have displaced large numbers of migrant families and their children. Decisions from both central and local governments have sought to reclaim control over new and changing social spaces. To achieve some of its goals around issues of both population management and social control, Beijing has undertaken an ongoing series of development projects which have coincided with the demolition of migrant children schools and structures in migrant communities – including some schools holding official permits. Ultimately, while the comparatively higher profile and larger-scale closures that occurred in 2006 and 2011 are in certain respects more indicative of landmark moments in the crackdown on migrant children schools in Beijing, it is essential to recognize that these types of occurrences have taken place on an ongoing basis throughout that time and continue to unfold in similar ways today.

Processes of maintaining separations in terms of space through the perpetuation of urban/rural divides, ensuring local-level bureaucratic regulation enforcement, and bifurcating potential interest convergences are in one sense being challenged while simultaneously in another sense being strengthened by education policies concerning migrant children, the implications of which raise critical questions about who is considered deserving – not only in terms of eligibility for public schooling but also in terms of for whom are these rules applicable. In addition, questions emerge related to which kinds of students are considered “traditional” or “worthwhile” in instances of transferring from one school to another, and which kinds of students are considered outsiders, as migrant children face relocation as a result of school closures.

Along similar lines to the kinds of questions being raised are concerns directed at migrant children schools. Discussed throughout this article are questions about the implicit intentions behind various policies, namely that regardless of the variety of stated aims, the consequences were the same: to suppress migrant children schools. Although there were countless claims about the rampant low quality of migrant children schools, it could be argued that such policies were always about eradicating migrant children schools and returning the children of migrant workers back to their places of origin. In addition, policies targeting migrant children schools did not include support for curriculum development, nor did they incorporate a direct focus on improving the academic achievement of migrant children. Similarly, there was no discussion of how improvements to pre-service or in-service teacher education might serve as an effective means towards addressing the educational quality issues commonly cited in the critiques of migrant children schools.

It is worth noting that both before and after policies impacting the education of migrant children were put in place, migrant children schools operated almost wholly outside of the official education system. These schools emerged as a response to the absence of schooling options for migrant children and operated for many years outside of the government's oversight with little repercussion. On the one hand, it is possible to claim that the schools were being closed as a result of a state-led crackdown thus leading to their decline. On the other hand, the decline coincided with a reduction in community interest and support as the belief that migrant children schools were of low quality and not a good option became widespread across the city and within the migrant communities. This is a result of strategic efforts by central and local governments and is evidence that perhaps speaks directly to the broader impact of education policies on how the public comes to regard particular schools.

Again, it is here that a broader understanding of the discursive functions of education policies offers a compelling explanation. Since in addition to establishing new rules and regulations, the policies impacting migrant children schools, communities and families were about altering and reframing what people's options regarding the education of their children were as well as changing how migrant children schools were perceived. With migrant children schools, the absence of direct policy-related regulation and oversight was in part what enabled their creation; however, with the later establishment of policies specifically targeting migrant children schools and students combined with the discursive interpellation of them, thus framing people's collective understandings of what the limits and possibilities of their actions are as it pertains to the education of migrant children, widespread public rejection of government actionFootnote 42 was fundamentally subverted.

Indeed, rather than seeing massive opposition to the closure of migrant children schools gain momentum, there continues to be a seemingly gradual collective acceptance of this, as individual families instead seek to navigate newly established rules, rather than acting outside of them, as those involved in migrant children schools had done previously. In other words, we see for the most part an acceptance of the policies and a shift in collective thinking about how to address the educational needs of migrant children. Arguably this shift is evidenced by a number of factors, most notable of which is the absence of a possible reimagining of the roles that migrant children schools play within migrant communities. Through an understanding of the discursive impact of the policies outlined throughout this paper, it becomes clearer how possible action or resistance within migrant communities is then rearticulated by the state so that individuals assume responsibility for meeting requirements such as having to obtain and produce an impossible number of forms in order to supposedly allow their children to attend school.

Conclusion and Implications

This study demonstrates and explores the complex functioning of education policies specifically affecting the education of migrant children, the schools responsible for educating them, and the migrant families who are attempting to provide their children with a formalized education. The interplay between notions of constraint and agency is key to policy analyses that recognize and/or consider the discursive functioning of education policies. In countless instances, migrant families have needed to send their children back to their hometowns in rural areas to continue their education despite having to endure long periods of separation. While the policies have offered a regulatory framework for transitioning migrant children to public schools, the impact has been much broader. In essence, these policies come to frame what people collectively assume to be possible regarding the education of migrant children in Beijing. This raises a number of important questions: Are these policies working effectively? How is effectiveness in this case being defined? For whom are these policies intended and who are the intended beneficiaries? And what will the long-term impact be?

Among Chinese policymakers there is a widespread and somewhat pernicious understanding of domestic migration wherein the dominant policy response has been to focus on controlling and limiting the movement of certain populations, especially as it relates to making adjustment in the provision of social services. Certain policies that seek or claim to address immediate concerns associated with both education and migration in particular, appear to demonstrate a profound lack of knowledge related to historical patterns of population movement and have in turn led to the reconfiguration of social infrastructure in ways that lag behind population changes and developments. Additionally, the deficit-driven conceptions of migrant workers and their families fuel beliefs that their contributions to cities fail to generate enough capital to justify their recognition as city residents and their inclusion in access to social services.

The establishment of new policies related to education and social welfare programmes are constructed in ways that indirectly, yet intentionally, exclude or marginalize the so-called “low-end population” (diduan renkou 低端人口) in order to achieve local governments’ goals of slowing residential population growth. Indeed, it remains a challenging and critical task for all levels of government to continually seek to improve both the quality and capacity of social services, including public education. Nevertheless, the proper administration of social infrastructure ought to remain a priority, given the inherent complexities that stem from demographic shifts and rapid population growth in order for people from marginalized and vulnerable populations not to feel silenced or as though they are being treated as a problem.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Manali Sheth, Jason Salisbury, and the editors and anonymous reviewers of The China Quarterly for their critical questions and comments on different drafts of this article. We are also grateful for the support from the Tashia F. Morgridge Distinguished Graduate Fellowship at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Biographical notes

Min YU is an assistant professor in the College of Education at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. Her research focuses on how changing social and political conditions affect the education of children from migrant and immigrant families and communities. She is the author of the book The Politics, Practices, and Possibilities of Migrant Children Schools in Contemporary China (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), and her work appears in journals such as Comparative Education Review, Review of Research in Education, and Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education.

Christopher B. CROWLEY is an assistant professor of teacher education at Wayne State University. His research focuses on issues related to the privatization of teacher education and the politics of education reform. His work critically examines how various stakeholders, including non-profit organizations, philanthropic foundations, the for-profit sector and others, are becoming increasingly involved in multiple aspects of teacher education. His research has appeared in journals such as Teaching and Teacher Education, Review of Research in Education, and Teacher Education & Practice.