Article contents

A Note On 'AΘΠ

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

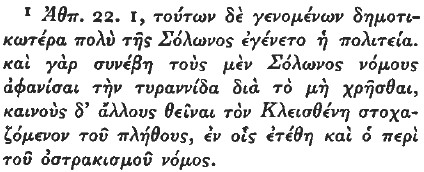

In 'AΘΠ. 22. I Aristotle made the judgement that Cleisthenes' reform gave a constitution to Athens far more democratic than Solon's, and to prove it he marked as Cleisthenic the law about ostracism. As the ostracism was considered a typically democratic institution, it was both persuasive and credible to connect Cleisthenes with a measure so admirably symptomatic of the adjudged new order.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1963

References

page 101 1

page 101 2 See Aristotle, , Politics 1284a17ff.Google Scholar, and Jacoby, , F. Gr. Hist. 3 B Suppl. ii. 227 f., n. 2.Google Scholar

page 101 3 Cf. Wilamowitz, , Arist. u. Athen, ii. 146.Google Scholar

page 101 4 F. Gr. Hist. 324 F 6.Google Scholar The recent suggestion by Kagan, , Hesperia xxx (1961), 394 f.Google Scholar, that Androtion did not date the ostracism law to 488/7, but rather had argued against its attribution to Theseus, would stultify Aristotle's insistence that the law was carried by Cleisthenes (see below, n. 5; similar attempts to disallow the contradiction of Androtion by Aristotle have been answered by Jacoby, , F. Gr. Hist. 3B Suppl. i. 119. 35 ff.Google Scholar). As Theseus, moreover, was not con sidered the founder of moderate democracy until the time of the publication of Androtion's Atthis (see Ruschenbusch, , Historia vii [1958], 408 ff.Google Scholar), Androtion can hardly have attempted the refutation of a theory implying that Theseus was founder of the radical democracy. Earlier references to Theseus by Euripides, e.g. Supplices 349 ff., 403 ff., relate to Theseus' ![]() and reflect the prestige of his position as national hero. To picture the hero as undemocratic in democratic Athens would have been as intolerable as to allow him to endure eternal punishment in Hades, from which, accordingly, the Athenians procured his release (see Wilamowitz, , S. B. Berl. [1925], 238).Google Scholar As Mme, de Romilly, R.É.G. lxxii (1959), 83Google Scholar, has suggested, the terms monarchy, tyranny, oligarchy, democracy were not used by the dramatist with nice discrimination: ‘quand un Athénien s'en prend à l'idée de tyrannie, il 1'oppose tout naturellement au bon régime, qui est la démocratic, et il ne regarde rien d'autre.’ Similarly, it is unlikely that Lysias in 2. 17–19 has precise constitutional information in mind, nor does the period to which he refers appear to exclude anything from Theseus to Marathon. See Walz, , Philologus Suppl. xxix Heft 4 [1936], 14, n. 35.Google Scholar

and reflect the prestige of his position as national hero. To picture the hero as undemocratic in democratic Athens would have been as intolerable as to allow him to endure eternal punishment in Hades, from which, accordingly, the Athenians procured his release (see Wilamowitz, , S. B. Berl. [1925], 238).Google Scholar As Mme, de Romilly, R.É.G. lxxii (1959), 83Google Scholar, has suggested, the terms monarchy, tyranny, oligarchy, democracy were not used by the dramatist with nice discrimination: ‘quand un Athénien s'en prend à l'idée de tyrannie, il 1'oppose tout naturellement au bon régime, qui est la démocratic, et il ne regarde rien d'autre.’ Similarly, it is unlikely that Lysias in 2. 17–19 has precise constitutional information in mind, nor does the period to which he refers appear to exclude anything from Theseus to Marathon. See Walz, , Philologus Suppl. xxix Heft 4 [1936], 14, n. 35.Google Scholar

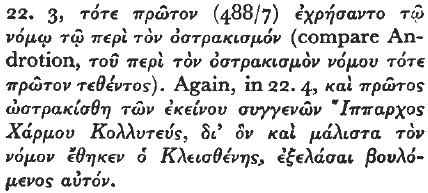

page 101 5 After the explicit statement in 22. 1 quoted in n. 1 above, Aristotle added in

page 102 1 Cf. 'AΘΠ. 10, where Aristotle corrected Androtion's account of the seisachtheia (Jacoby, , F. Gr. Hist. 324 F 34Google Scholar, with com mentary; cf. Busolt, , Griech. Gesch. ii 2. 41 n. 2).Google Scholar Modern scholars, e.g. Sumner, C.Q. N.s. xi (1961), 36Google Scholar, rightly demand such dis cussion from Aristotle; that it be presented explicitly is not always in the manner of the 'AΘΠ.

page 102 2 Aristotle reverted to the opinion held by Hellanikos (see Jacoby, , F. Gr. Hist. Suppl. i. 120. 9–12Google Scholar) and probably, though the frag ments yield no clue, by Kleidemos also. Androtion's departure from what seems to have been the ‘orthodox’ view is therefore a good deal more surprising than Aristotle's return to it; the question ‘why Aristotle should have gone out of his way to reject Androtion's date’ (so Hands, , J.H.S. lxxix [1959], 71)Google Scholar largely finds its answer in the reason for Androtion's having gone out of his way to change Hellanikos' date, on which see Jacoby, , F. Gr. Hist. 3 B Suppl. i. 120. 16–23Google Scholar, and, more recently, Ruschenbusch, , Historia vii (1958), 412.Google Scholar As in the case of the seisachtheia (see n. 1), Aristotle corrected Androtion because the latter sought to use or fabricate a tradition suitable to his political viewpoint but inimical to Aristotle's, who con sidered Cleisthenes, not Aristeides-Ephialtes, the founder of the radical democracy.

page 102 3 See also Jacoby, , F. Gr. Hist. 3 B Suppl. i. 121.Google Scholar 16 ff., who, though he well understood Aristotle's tendentious motive for writing 22. 3 ff., did not consider the relevance of 22. 2. The transmutation of ή ![]() (22. 4) into self-assurance,

(22. 4) into self-assurance, ![]() leading to the Athenians' eventual use of the ostracism, is charted by the measures listed in 22. 2. In the same fashion Aristotle explained the Athenian seizure of empire ('AΘΠ. 24) by postulating a further increase of self-confidence (24. 1) derived from building the walls of Athens and replacing Sparta as leader of the Ionian allies (23. 3 ff.).

leading to the Athenians' eventual use of the ostracism, is charted by the measures listed in 22. 2. In the same fashion Aristotle explained the Athenian seizure of empire ('AΘΠ. 24) by postulating a further increase of self-confidence (24. 1) derived from building the walls of Athens and replacing Sparta as leader of the Ionian allies (23. 3 ff.).

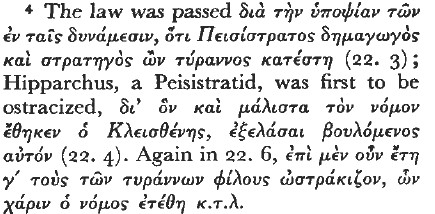

page 102 4

page 102 5 ![]() syllogistic (see Kuhner-Gerth, , Ausf. Gramm. ii. 154 f.Google Scholar) signals that

syllogistic (see Kuhner-Gerth, , Ausf. Gramm. ii. 154 f.Google Scholar) signals that ![]()

![]() introduce co-ordinate members of a chronological argument (see p. 104, below) supporting the previous

introduce co-ordinate members of a chronological argument (see p. 104, below) supporting the previous ![]() of Anchimolus is cited as proof of Aristotle's preceding contention that the Spartans were induced by the Delphic oracle to turn against the Peisistratids in spite of bonds of guest-friendship. The logical structure of the two arguments differs merely in its com plexity. 22. 2 is a kind of negative proof (by necessity: the different dating by Androtion and Aristotle without citation of docu mentary evidence by the latter shows that it did not exist), an elaborate explanation for delay in the use of the ostracism. In 19. 5 Aristotle had positive evidence to offer.

of Anchimolus is cited as proof of Aristotle's preceding contention that the Spartans were induced by the Delphic oracle to turn against the Peisistratids in spite of bonds of guest-friendship. The logical structure of the two arguments differs merely in its com plexity. 22. 2 is a kind of negative proof (by necessity: the different dating by Androtion and Aristotle without citation of docu mentary evidence by the latter shows that it did not exist), an elaborate explanation for delay in the use of the ostracism. In 19. 5 Aristotle had positive evidence to offer.

page 103 1 The passages are collected by Busolt-Swoboda, , Griech. Staatsk., p. 1023 n. I.Google Scholar

page 103 2 See Griech. Staatsk., p. 1007 n. 4.Google Scholar

page 103 3 See Griech. Staatsk., pp. 233 f. n. 1, 1023 n. 1Google Scholar; Wilamowitz, , Arist. u. Athen i. 54, ii. 78.Google Scholar

page 103 4 See p. 104, below.

page 103 5 i.e. it is a reminder that the strategia had not yet attained its full growth of impor tance.

page 103 6 Aristotle made the connexion between ![]() and the generals in the case of Themistocles (23. 3). He joined the terms

and the generals in the case of Themistocles (23. 3). He joined the terms ![]() when speaking of Peisistratus (22. 3; cf. Politics 1305a7), whose nature was

when speaking of Peisistratus (22. 3; cf. Politics 1305a7), whose nature was ![]() (16. 8). He ignored, it is true, the importance of the strategia during the fifth century and the repeated tenure of that office by Pericles, but as Niese, , Hist. Zeit. lxix (1892), 42, observed, it would not have been convenient to discuss the external success of the radical democracy.Google Scholar

(16. 8). He ignored, it is true, the importance of the strategia during the fifth century and the repeated tenure of that office by Pericles, but as Niese, , Hist. Zeit. lxix (1892), 42, observed, it would not have been convenient to discuss the external success of the radical democracy.Google Scholar

page 103 7 One consequence of the reform possibly relevant to Aristotle's present purposes was that the Demos, by ![]() ('AΘΠ. 61.2), secured and exercised continual super vision over the leaders of its armies. Aristotle may have also considered that the electo ral procedure provided for this magistracy itself reflected a heightening of the self-confidence of the Demos and facilitated its further acceleration (see Politics 1305a29–36). Perhaps most important, it is a strategos, Miltiades, who was chiefly responsible for the victory of 490.

('AΘΠ. 61.2), secured and exercised continual super vision over the leaders of its armies. Aristotle may have also considered that the electo ral procedure provided for this magistracy itself reflected a heightening of the self-confidence of the Demos and facilitated its further acceleration (see Politics 1305a29–36). Perhaps most important, it is a strategos, Miltiades, who was chiefly responsible for the victory of 490.

page 103 8 Hence, Aristotle would say, a perversion of the original intent of the law (see New man's note ad Politics 1284a17), but a pre dictable consequence of the triumph of radical democracy restrained ultimately by nothing more than the ![]()

![]() .

.

page 103 9 Hist. Zeit. lxix (1892), 42Google Scholar: ‘Der ganze Abschnitt ist eine summarische Charakteri-stik der Demokratie nach ihren Ursachen und Wirkungen im Sinne der politischen Theorie.’

page 104 1 For a discussion of the problem see Cadoux, , J.H.S. lxviii (1948), 115f.Google Scholar, and, mostrecendy, Sumner, C.Q. N.S. xi (1961), 36.Google Scholar

page 104 2 e.g. Busolt, , Griech. Gesch. ii 2. 431 n. 4Google Scholar; Hignett, , A History of the Athenian Constitution, p. 166.Google Scholar

page 104 3 Sumner, , loc. cit., p. 36Google Scholar; cf. Gomme, , J.H.S. xlvi (1926), 176 n.Google Scholar Sumner refines Schachermeyr's suggestion, Klio xxv (1932), 347Google Scholar, that the ![]() extended to 505/4, when (on that view) the ostracism law was carried. Hignett, , op. cit., p. 337Google Scholar, rightly found this explanation untenable; the predication of a lacuna (difficult in itself: the text is coherent as it stands, and not a trace of the information presumed missing recurs elsewhere) hardly obviates all its difficulties. Aristotle, moreover, could not have dated the ostracism law to 505/4 (rather than to 508/7) unless he had documentary evidence, and the dispute widi Androtion shows that none was extant. Perhaps there is, however, another and simpler way to save the ordinal. 507/6, as it was the first year of the new régime, may have figured in the constructions of the Atthidographers as the year of the

extended to 505/4, when (on that view) the ostracism law was carried. Hignett, , op. cit., p. 337Google Scholar, rightly found this explanation untenable; the predication of a lacuna (difficult in itself: the text is coherent as it stands, and not a trace of the information presumed missing recurs elsewhere) hardly obviates all its difficulties. Aristotle, moreover, could not have dated the ostracism law to 505/4 (rather than to 508/7) unless he had documentary evidence, and the dispute widi Androtion shows that none was extant. Perhaps there is, however, another and simpler way to save the ordinal. 507/6, as it was the first year of the new régime, may have figured in the constructions of the Atthidographers as the year of the ![]() (never formally dated by Aristode: he assigned the passage of the reforms to 508/7 (22. 1); diey cannot have become operative until the following year: cf. Wilamowitz, , Arist. u. Athen, ii. 417 n.Google Scholar; Busolt, , Griech. Gesch. ii 2. 403 n.Google Scholar; Cadoux, , J.H.S. lxviii [1948], 114.Google Scholar Hence Pollux, , 8. 110Google Scholar,

(never formally dated by Aristode: he assigned the passage of the reforms to 508/7 (22. 1); diey cannot have become operative until the following year: cf. Wilamowitz, , Arist. u. Athen, ii. 417 n.Google Scholar; Busolt, , Griech. Gesch. ii 2. 403 n.Google Scholar; Cadoux, , J.H.S. lxviii [1948], 114.Google Scholar Hence Pollux, , 8. 110Google Scholar, ![]()

![]() . For Alcmaeon see Hesychius, s.v.

. For Alcmaeon see Hesychius, s.v. ![]() ). If that is so, Hermocreon's year will have been 503/2.

). If that is so, Hermocreon's year will have been 503/2.

page 104 4 On numbers in the 'AΘΠ. see Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 379 n. 141.Google Scholar

page 1045 Thus Schachermeyr's assertion, Klio xxv (1932), 346 n. 2Google Scholar, that Aristotle's mode of expression indicates diat botib measures were passed in the same year is baseless.

page 1046 See p. 102 n. 5 above.

- 5

- Cited by