Article contents

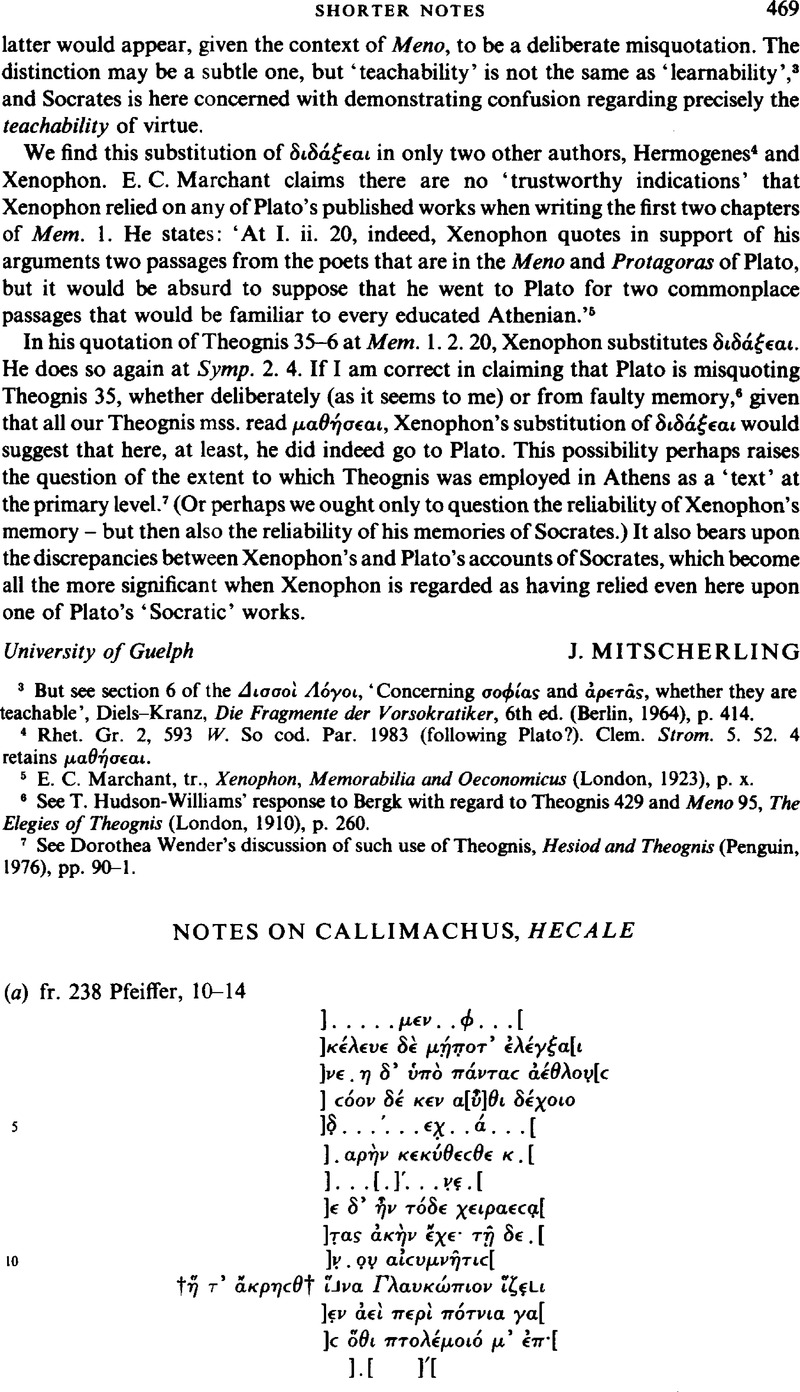

Notes on Callimachus, Hecale

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Shorter Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1982

References

1 Kassel preferred ![]()

2 What precedes is a real puzzle. The scribe has written ὺπo with a grave accent, which should mean that we do not have ὔπo in anastrophe. After ]νε most likely seems iota (Mr P. J. Parsons agrees, but says that Y or even P cannot be totally excluded). If so, we would appear to be faced with εἳη from ἳημι, or εἳη, whether from ἰεμμί sum or ![]() ibo (see Macleod on Iliad 24. 139). W. S. Barrett, judging from the photograph, thought the next letter could as well be N as H; certainly ]νειν would open up fresh possibilities. P. J.P. agrees that H can be very similar to N in this hand, but, having re-examined the original papyrus, still believes that the letter is H.

ibo (see Macleod on Iliad 24. 139). W. S. Barrett, judging from the photograph, thought the next letter could as well be N as H; certainly ]νειν would open up fresh possibilities. P. J.P. agrees that H can be very similar to N in this hand, but, having re-examined the original papyrus, still believes that the letter is H.

3 Rather than to fr. 253. 2 (as Pfeiffer), where Theseus probably mentions to Hecale his guidance by Athena (even though the restoration ![]() hardly fits the traces of the last letter, according to Lloyd-Jones and Parsons on their Supplementum Hellenisticum no. 285). One is reminded of the help given by Athena in another myth treated by Callimachus, Heracles and the Nemean lion (fr. 57. 4; see now Parsons ZPE 25 [1977], 41). For the Nemean lion in the Hecale (? as a parallel to the Marathonian bull) cf. fr. 339

hardly fits the traces of the last letter, according to Lloyd-Jones and Parsons on their Supplementum Hellenisticum no. 285). One is reminded of the help given by Athena in another myth treated by Callimachus, Heracles and the Nemean lion (fr. 57. 4; see now Parsons ZPE 25 [1977], 41). For the Nemean lion in the Hecale (? as a parallel to the Marathonian bull) cf. fr. 339 ![]()

![]() . Comparison of the labours of Theseus with those of Heracles was of course a commonplace, e.g., from the passage of Statius just cited, Theb. 12. 584 nee sacer invideat paribus Tirynthius actis. It is possible that Catullus 64, when speaking of Aegeus, Theseus and the Minotaur, makes use of relevant passages in the Hecale. The most striking resemblance is between Cat. 64. 111 nequiquam vanis iactantem comua ventis and Call. fr. 732 incerti auctoris (plausibly assigned to the Hecale)

. Comparison of the labours of Theseus with those of Heracles was of course a commonplace, e.g., from the passage of Statius just cited, Theb. 12. 584 nee sacer invideat paribus Tirynthius actis. It is possible that Catullus 64, when speaking of Aegeus, Theseus and the Minotaur, makes use of relevant passages in the Hecale. The most striking resemblance is between Cat. 64. 111 nequiquam vanis iactantem comua ventis and Call. fr. 732 incerti auctoris (plausibly assigned to the Hecale) ![]()

![]() . Note also more generally (a) Aegeus' dread that he will lose the son whom he has so recently met for the first time (cf. Call. Diegesis x. 18. 21–3 and fr. 260. 7) in Catullus 64. 215—17 gnate, mihi longa iucundior unice vita, | gnate, ego quern indubios cogor dimittere casus | reddite in extrema nuper mihi fine senectae and (b) the help of Athena, protectress of the city, in overcoming the monster (which I believe may be the theme of Call, fr. 238. 1–14), ibid. 228–30 quod tibi si sancti concesserit incola Itoni, | quae nostrum genus ac sedes defendere Erecthei | annuit, ut tauri respergas sanguine dextram.

. Note also more generally (a) Aegeus' dread that he will lose the son whom he has so recently met for the first time (cf. Call. Diegesis x. 18. 21–3 and fr. 260. 7) in Catullus 64. 215—17 gnate, mihi longa iucundior unice vita, | gnate, ego quern indubios cogor dimittere casus | reddite in extrema nuper mihi fine senectae and (b) the help of Athena, protectress of the city, in overcoming the monster (which I believe may be the theme of Call, fr. 238. 1–14), ibid. 228–30 quod tibi si sancti concesserit incola Itoni, | quae nostrum genus ac sedes defendere Erecthei | annuit, ut tauri respergas sanguine dextram.

4 Metre appears to guarantee what placing on the papyrus would leave very much in doubt - that ![]() is the final word of line 10. A hexameter-ending of the pattern

is the final word of line 10. A hexameter-ending of the pattern ![]()

![]() would not be Callimachean (Maas, Greek Metre [tr. Lloyd-Jones] para. 93, ‘ Lines with masculine caesura have a secondary caesura either (a) after the seventh element, or (b) after the eighth element’).

would not be Callimachean (Maas, Greek Metre [tr. Lloyd-Jones] para. 93, ‘ Lines with masculine caesura have a secondary caesura either (a) after the seventh element, or (b) after the eighth element’).

5 Curiously neither Ida Kapp (Callimachi Hecalae fragmenta [1915], p. 59) nor Pfeiffer seems even to consider that ![]() may be the true reading.

may be the true reading.

6 One could complete the line by adding ![]() after

after ![]() (Dindorf [cf. Schneider fragm. anon. 332], favoured by Barrett). But it does not seem necessary to postulate omission when there are other possibilities - e.g.

(Dindorf [cf. Schneider fragm. anon. 332], favoured by Barrett). But it does not seem necessary to postulate omission when there are other possibilities - e.g. ![]() could perhaps stand alone (recognized by LSJ = ‘hilltop’, ‘height’, or, at least in prose, ‘citadel’).

could perhaps stand alone (recognized by LSJ = ‘hilltop’, ‘height’, or, at least in prose, ‘citadel’).

7 I would take ![]() together (Barrett-on this point Naeke hesitated), ‘the Glaucopian mound’.

together (Barrett-on this point Naeke hesitated), ‘the Glaucopian mound’.

8 Meineke supplied ὅν, Bergk ὡς.

9 Pfeiffer was very doubtful about the future optative, and suggested ![]() .

.

10 If ![]() is to be distinguished in line 1 (probable, though as well as compounds there are also e.g.

is to be distinguished in line 1 (probable, though as well as compounds there are also e.g. ![]() as Barrett points out), Callimachus’ respect for Hermann's Bridge (Maas, Greek Metre paras. 87 and 91, though e.g.

as Barrett points out), Callimachus’ respect for Hermann's Bridge (Maas, Greek Metre paras. 87 and 91, though e.g. ![]() would be possible) and his dislike for ending with the second trochee a word beginning in the first dactyl (see Williams on hymn 2. 41 for the few exceptions) cut down the number of places in the hexameter where this word can stand. We would be left with the line-ending, or immediately before the feminine caesura (as hymn 3. 109

would be possible) and his dislike for ending with the second trochee a word beginning in the first dactyl (see Williams on hymn 2. 41 for the few exceptions) cut down the number of places in the hexameter where this word can stand. We would be left with the line-ending, or immediately before the feminine caesura (as hymn 3. 109 ![]() ). Against the line-ending (even if not decisively so), Barrett notes that in fr. 238 (fr. 1 of this papyrus) the text on recto and verso is so positioned that the last letters (up to 8) of the lines on recto and verso are backed by blank papyrus before line-beginnings on verso and recto; but our fragment (fr. 3v) is backed by writing on the recto. The upshot is that, if we are to identify fr. 311 in line 2, a placing immediately above

). Against the line-ending (even if not decisively so), Barrett notes that in fr. 238 (fr. 1 of this papyrus) the text on recto and verso is so positioned that the last letters (up to 8) of the lines on recto and verso are backed by blank papyrus before line-beginnings on verso and recto; but our fragment (fr. 3v) is backed by writing on the recto. The upshot is that, if we are to identify fr. 311 in line 2, a placing immediately above ![]() of

of ![]() before the feminine caesura would fit well.

before the feminine caesura would fit well.

11 Pfeiffer vol. u, pp. xxviii-xxix. For a cautionary note about Hecker's view (endorsed by Pfeiffer vol. I, p. 228) that all anonymous and otherwise unknown dactylic fragments in the Suda come from the Hecale, see P. J. Parsons, ZPE 25 (1977), 50.

12 Frs. 260–1 with the improved and up-dated text of Lloyd-Jones and Rea, HSCP 72 (1968), 125–45.

13 Lobel, however, remarks (P. Oxy. vol. 19 (1948), 145–6) that, while fr. 2 may well come from the immediate neighbourhood of fr. 1, on the other hand fr. 3 is stained a dark colour, and has no special resemblance to frs. 1 and 2 apart from the writing.

14 Following the supplements given by Pfeiffer (see his notes for their origin), Lloyd-Jones and Parsons do not include these in their Supplementum Hellenisticum no. 285; before δε in line 2 they see traces of a letter hardly consistent with the sigma which ![]() would require.

would require.

15 Both Naeke (Callimachi Hecale [1845], p. 156) and Ida Kapp (Callimachi Hecalae Fragmenta [1915], p. 84) thought of this context in the Hecale. Schneider (Callimachea vol. Ii [1873], p. 181), amid some implausible ideas, has one remarkable piece of divination: ‘deinde quum Theseus quoque Hecalae talis viri adventum miranti breviter narrasset quis esset et unde cur iret, rursus ex Hecale quaesivit quo casu factum esset, ut in hac solitudine habitaret (before the papyrus came to light!). Turn ilia contristata est, ![]() (fr. 313 Pf., but this is poor judgement - if

(fr. 313 Pf., but this is poor judgement - if ![]() opened Hecale's speech,

opened Hecale's speech, ![]()

![]() must have belonged elsewhere) dixitque

must have belonged elsewhere) dixitque ![]() ;’.

;’.

16 The papyrus and the Suda have ὑπ⋯ rather than περί (Choeroboscus), which Pfeiffer preferred.

17 The main credit for determining this goes to Bartoletti, SIFC 31 (1959), 179–81.

18 Barrett questions whether her prosperity was ever more than modest, since fr. 255 shows her taking an active part in the farming operations - an interesting point, but perhaps ![]() need not imply more than a supervisory visit to the work (Sir Kenneth Dover). W. S. B. also suspects that in fr. 254. 2 TO τ⋯ τρίτoν means ‘for the third time’ (as e.g. in fr. 75. 18), with the sense being made clear by subsequent lines.

need not imply more than a supervisory visit to the work (Sir Kenneth Dover). W. S. B. also suspects that in fr. 254. 2 TO τ⋯ τρίτoν means ‘for the third time’ (as e.g. in fr. 75. 18), with the sense being made clear by subsequent lines.

19 For Demeter in this same context one can add Ovid, Fasti 4. 517 simularat anum.

20 If my idea were correct, the Hecale would of course become more than likely, since the only other fragmentary poem at present known to have been in hexameters is the Galatea (frs. 378–9). It is possible, however, that (even if the association is right) fr. 611 and fr. 490 might have been adjacent rather than consecutive, in which case a pentameter could have intervened.

21 For the names of the well and the topography, see Richardson on Dem. 99, and his Appendix I.

22 = Lloyd-Jones and Parsons, Supplementum Hellenisticum no. 287(b), 19–20.

23 In which case note fr. 705 incertae sedis ![]() . But the ancient sources are by no means agreed as to who enjoyed the remission of ferry-dues and why (see Pfeiffer on fr. 278). The Suda, perhaps from the commentary of Salustius, says puzzlingly

. But the ancient sources are by no means agreed as to who enjoyed the remission of ferry-dues and why (see Pfeiffer on fr. 278). The Suda, perhaps from the commentary of Salustius, says puzzlingly ![]() . Barrett observes that

. Barrett observes that ![]() and

and ![]() are not so different to the eye, and that

are not so different to the eye, and that ![]() (incidentally mentioned in Call. fr. 238.23) is the name of a ridge between Athens and Eleusis (from which Xerxes watched the battle of Salamis, Hdt. 8. 90. 4). For traditions that the descent of Persephone took place at Eleusis, see Richardson, H.H. Dem. p. 150, but there is no evidence that (presumably) the Eleusinians were granted remission of their ferry-dues.

(incidentally mentioned in Call. fr. 238.23) is the name of a ridge between Athens and Eleusis (from which Xerxes watched the battle of Salamis, Hdt. 8. 90. 4). For traditions that the descent of Persephone took place at Eleusis, see Richardson, H.H. Dem. p. 150, but there is no evidence that (presumably) the Eleusinians were granted remission of their ferry-dues.

24 I am extremely grateful to Mr P. J. Parsons for papyrological advice, and to Mr W. S. Barrett for detailed comments on these notes.

- 1

- Cited by