No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

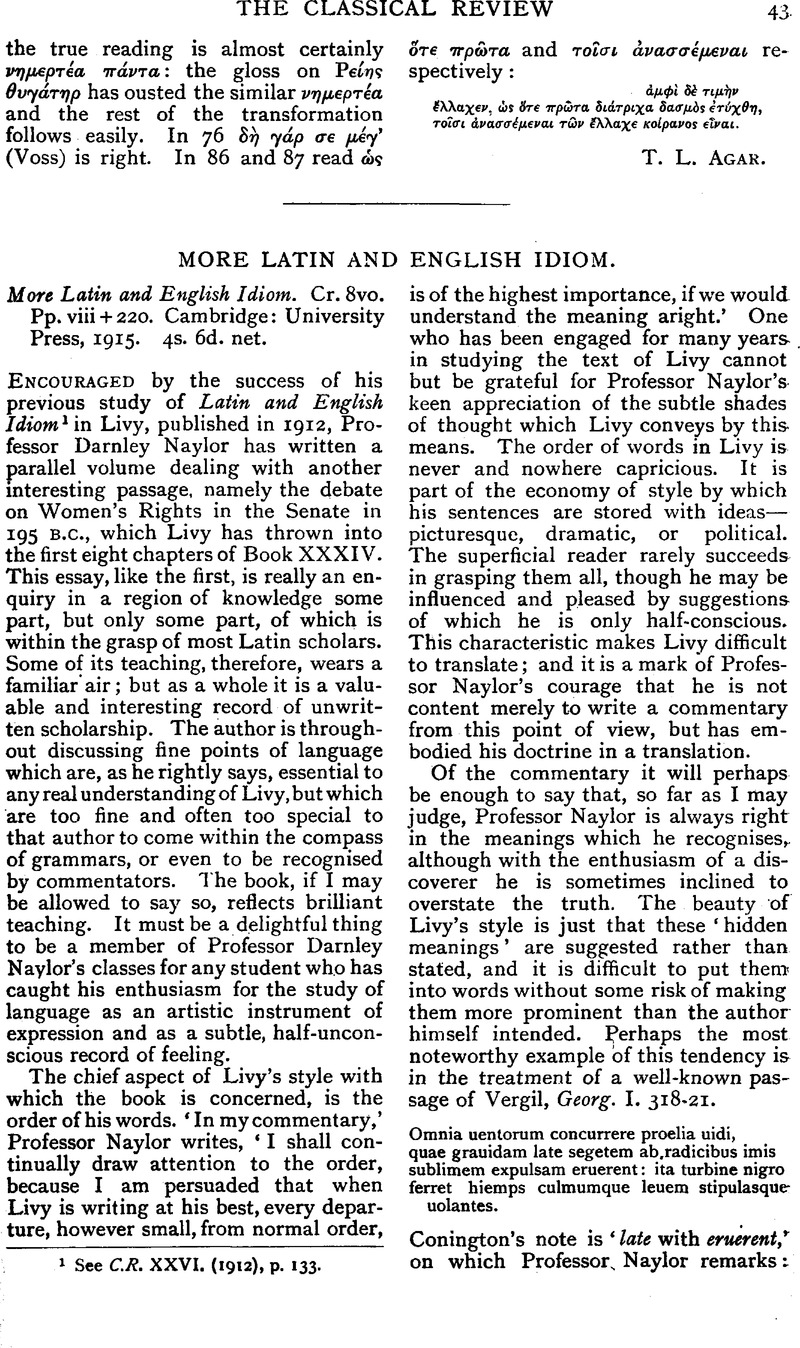

More Latin and English Idiom

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1917

References

page 43 note 1 See C.R. XXVI. (1912), p. 133.

page 44 note 1 I may perhaps add that Professor Naylor's suggestion of changing the difficult ita into ut seems to be excluded by the ordinary rule of critical probability; so easy a reading as ut is not at all likely to be turned out by so difficult a reading as ita; and the theory of such a corruption in the text of the Georgics is one which few serious students of that text will be prepared to entertain. The truth surely is, though I have not seen it stated, that the clause ita … ferret is an oblique command given by the same unnamed authority as inspired the purpose expressed by eruerent. In English we have no such simple machinery for expressing an oblique command without naming the author of it. ‘Sent to uproot the ripe harvest from wide fields, with a bidding to the storm forthwith to carry off in its dark eddies the light chaff and flying straw.’ Instead of an oblique command some may prefer to call it an expression of Past Obligation like the Plautine non redderes, which comes to the same thing.

page 45 note 1 The matter is discussed in my note on Livy II. 1. 3 (Camb. Univ. Press, 19O1).

page 45 note 2 Professor Naylor uses this symbol (>) in neither of the two senses about which German scholars have disputed ad nauseam. It is so liable to misinterpretation in matters of language that (like the fatal =) it should be made a penal offence. On a blackboard the arrows →, to mean ‘passes into,’ and ← to mean ‘arist s from,’ are no doubt harmless ; but need we read our books in an atmosphere of powdered chalk?