In the summer of 1934, over 500 women gathered in London at the annual conference of the International Co-operative Women's Guild. The International Guild was founded in the wake of the First World War, made up of women members of the co-operative movement across Europe, and was often referred to as the ‘international of mothers’ by its president.Footnote 1 A delegate speaking at the conference argued that as wives and mothers, women needed to recognise that fascism posed an imminent threat to the safety and security of their families. This representative from England, Florence Ranson, called attention to the danger, asking her fellow representatives:

don't you know what Fascism means, underneath its glories? War! – taking our children as in 1914. There is a big, dark, blood-dripping cloud hanging over us, the cloud of war. If we do not realise that, we deserve to have our sons taken away from us. We need to see further into the future, and realise that the responsibility is in our hands.Footnote 2

Ranson gave her speech as a delegate of the Women's Co-operative Guild in England, a women's organisation with over 70,000 members, made up primarily of working-class housewives.Footnote 3 She was therefore not alone in her belief that women had to work together to avoid a future war. Additionally, as historians such as Leila Rupp, Karen Offen and Christine Bolt have noted, many members of the broader international women's movement in the interwar period also contended that mothers, lest they lose their sons as Ranson predicted, had a particular duty to campaign for disarmament and build a lasting international peace.Footnote 4

By 1933 women's organisations in Britain had expressed growing concerns about the spread of fascism to Germany and what it might mean for the status of women across national borders. This was alarming because it represented the international spread of a movement that the majority of feminist activists in Britain identified as reactionary in terms of women's rights.Footnote 5 Fascism signified a retreat toward a past when women had even fewer rights and disputes were settled with military force, trends that were inextricably connected in the minds of many members of the women's movement.Footnote 6 Their concerns grew as fascist governments implemented policies that feminists condemned for pushing women out of politics and back into the home, prescribing limited roles for women as wives and mothers. British women active in the interwar women's movement worried that these policies could be enacted in Britain, and indeed drew connections between the conservative National Government in Britain and fascist governments. British feminists, for instance, protested measures aimed at undercutting women's economic rights, such as the imposition of the marriage bar which forced women to leave their employment once they were married, as well as the British government's unwillingness to take a leadership role in international disarmament, as it remained committed to using military force to police its empire.

Many women, like Ranson, understood fascism to be synonymous with militarism and war. While British feminists had a variety of gendered responses to international conflict and fascism, they continued, as they had during the First World War, to associate women with motherhood and peace.Footnote 7 In these campaigns women's organisations frequently relied on maternalist arguments, advocating for women's involvement in public politics based on their biological and socially constructed roles as mothers, which feminists had long utilised in order to advocate for pacifism and women's involvement in the making of public policy.Footnote 8 In the same decades in which some British feminists sought to claim maternalism as a force for political and social change in their campaigns for birth control, abortion rights and disarmament, however, fascist regimes emphasised women's roles as wives and mothers to encourage women to produce future soldiers and push women out of political decision making.Footnote 9

This article builds on the work of historians, most notably Julie Gottlieb, who have persuasively argued that women's feminist politics had a significant impact on how these activists understood the threat of fascism and worked to counter it.Footnote 10 While not all members of the British women's movement in the interwar period embraced the label of feminist for themselves due to disputes over the meanings and connotations of the term, I use feminist to indicate individuals and organisations that advocated for the emancipation of women, including calling for women's political and legal equality with men as well as women's social and economic rights.Footnote 11 Additionally, Gottlieb, along with historian Johanna Alberti, has pointed to fractures within the women's movement resulting from women's anti-fascist activism, in particular over whether organisations and individuals remained committed to pacifism in the face of rising fascist aggression and debates about appeasement over the course of the 1930s.Footnote 12 The scholarship of Gottlieb, in addition to the work of Astrid Swenson and more recently Mercedes Yusta Rodrigo, has also highlighted that feminists often portrayed women as natural anti-fascists, and used maternalist arguments to oppose fascism and war.Footnote 13 This article re-examines the maternalist and pacifist arguments made by feminists who opposed fascism, and does not assume that fascist and feminist politics had nothing in common, despite the fact that feminists so often claimed that their politics were naturally anti-fascist. Instead it considers how British women's organisations responded as fascist governments and leaders emphasised the special role of women as mothers at the same time that many feminist organisations also emphasised the unique role of women as mothers in advocating for a better future for women, particularly through women's work for peace. It seeks to understand how and why certain feminist groups were able to retain their commitment to maternalist rhetoric while at the same time responding to the threat of fascism.

What follows is an examination of the discourses of two prominent interwar feminist organisations, the National Union of Women Teachers and the Women's Co-operative Guild, analysed alongside the rhetoric of prominent members of the women's movement and the organisations to which they belonged. This analysis focuses on the organisational records of the NUWT and the Guild as well as the periodicals published by both groups that were primarily intended to be circulated among members and others sympathetic to their causes. These sources reveal that the leadership and members of both organisations were committed to women's work for peace and troubled by fascist militarism, pronatalism and the impact that fascism could have on the women's movement. These concerns were also shared by other members of the women's movement, and a survey of publications produced by prominent interwar women's organisations, along with the popular press, demonstrates that fascism influenced the discourses surrounding motherhood, reproduction, war and peace among feminists. In highlighting these dynamics this article contributes to recent scholarship, such as that of Caitríona Beaumont, which sheds new light on the diverse reasons why women, across the broad spectrum of the women's movement, campaigned for peace.Footnote 14

This article will demonstrate that while members of the British women's movement had long embraced women's biological and social roles as mothers to reinforce their position as advocates for peace, feminist opposition to fascist politics and policies forced a reconsideration of this emphasis as fascist governments highlighted women's roles as mothers for an altogether different purpose. Rather than wholly rejecting essentialist maternalist arguments about women's nurturing roles as mothers and caretakers of children, some British feminist activists supported women exercising control over their own bodies and reproduction as a means to counter the rise of fascism and to reinforce their work for peace in order to prevent their children from falling victim to, or fighting in, future wars. This article thus contributes to the intertwined histories of feminist activism, the international peace movement and anti-fascism by illustrating how British women's organisations navigated complex politics at home and abroad. It highlights that the rhetoric and commitments of domestic feminist movements were profoundly shaped by the international politics of both fascism and anti-fascism.

War and the Nursery: Children as Future Soldiers and Future Victims

Many women's organisations and feminists highlighted women's ‘natural’ connection to peace activism and the promotion of internationalism well before fascism was perceived as a threat. After the devastation of the Great War, many feminists believed that women would bring a new way of thinking to politics as recently enfranchised voters and holders of political office. The pacifist and feminist Helena Swanwick, a founding member of the pacifist women's organisation the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, acknowledged that women, along with men, had supported the war, but believed that with the gains of feminism an increasing number of ‘independent-minded women’ would realise that ‘future war will destroy the race of which they are the cradle, and they will not have it’.Footnote 15 Relying on mothers’ connection to their children as inspiration for their work in support of feminist internationalism, Swanwick articulated a vision of maternalist pacifism that she hoped all women would eventually adopt.

The idea that women had a unique perspective on war and politics was shared by many within and outside of the women's movement. Feminists and non-feminists alike considered women to be ‘natural pacifists’ and therefore less likely than their male counterparts to use war as a means to settle conflicts. This argument stemmed from the gendered belief that as givers of life women had an inherent desire for peace rather than war.Footnote 16 However, activists disagreed over to what extent, if any, women's views were a result of essential differences between the sexes or a product of differences in the education and opportunities afforded to women.Footnote 17 Virginia Woolf, for instance, argued the latter in her seminal feminist and anti-fascist text, Three Guineas.Footnote 18 By the 1920s, violence was not always equated with maleness, but was often linked to the way that men were educated, for instance, by taking part in military drills in schools or learning history from nationalist and militaristic textbooks.Footnote 19 Because of this, members of the Women's Co-operative Guild viewed mothers and teachers as highly influential figures in campaigns to secure a lasting international peace. Throughout the interwar period, the Women's Co-operative Guild used women's social roles as mothers in order to advance its pacifist agenda.Footnote 20 Recognising the influential role that childhood experiences had on adult citizens, the Guild discouraged parents from giving toy guns to their children at Christmas and opposed military training and drilling in schools throughout the interwar period.Footnote 21

The National Union of Women Teachers, a feminist trade union, also emphasised the important role that early education had on influencing the politics of adults.Footnote 22 Leaders of the NUWT argued that teachers played a crucial role in instilling a commitment to peace rather than war in their young students. The NUWT therefore called on its members to support international disarmament and to oppose government spending on armaments, noting that these funds would be much better spent supporting children's education.Footnote 23 Furthermore, NUWT members argued that their commitment to peace also stemmed from their position as ‘Feminists, as Citizens, and as Educators’, noting that countries with the strongest culture of militarism were the same countries where women had the fewest rights.Footnote 24 This linking of peace work to feminist activism ensured that the NUWT remained committed to peace work throughout the 1930s, both inside and outside of the schools in which they worked.

Members of these British feminist organisations thus took issue with a broad range of policies which they viewed as promoting fascist militarism. The militaristic education of boys in Germany was alarming for women who were trying to counteract the belligerent desires of boys and men within their own families.Footnote 25 They challenged not only fascist governments’ funding for war preparations and disregard for disarmament, but also the notion that women's roles as mothers should be supported as a means to produce future soldiers. Ethel Stead, of the NUWT, argued that militarism inevitably led to setbacks in the progress of the women's movement, due to the ‘age-long antagonism between Feminism and Militarism’.Footnote 26 For Stead, it was no coincidence that in Italy and Germany women were pushed out of public positions and encouraged to produce children for the state. The leadership of the National Union of Women Teachers also argued that fascist governments were militaristic, and ‘since any military state must necessarily be anti-feminist’, it was their duty as feminists to work against fascism and war.Footnote 27

Concern about the birth rate and the ‘health’ of the nation predated the Nazi regime in Germany, but the Nazi government employed a variety of strategies in the interwar period to try to counter what was perceived as a threat to the health of the German nation. The drop in the German birth rate in the 1920s to historically low levels was viewed by contemporaries across the political spectrum as a matter of concern. After coming to power, Nazi officials publicly emphasised the importance of the family and stressed that those families deemed ‘racially fit’ or ‘valuable’ should be large, ideally with at least four children. The encouragement of ‘Aryan’ couples to get married and have children coincided with the development of the ‘cult of motherhood’ in Germany which emphasised women's roles as wives and mothers within the home.Footnote 28 Nazi attempts to increase the birth rate through policy included ‘the Marriage Loan Scheme; the Cross of Honour of the German Mother; the introduction of a new divorce law in 1938; the banning of contraceptives and the closure of family planning centres; the tightening up of abortion laws; and welfare for mothers and children’.Footnote 29 The number of marriages and births did increase overall in Germany under the Nazi regime in the 1930s, but these policies were not very effective in encouraging individual families to have more children. Historians also argue that the increase that did occur in marriages and births had perhaps more to do with an improving German economy rather than Nazi family policy.Footnote 30 At the same time that the Nazi government was encouraging the formation of large ‘Aryan’ families, it was also forcibly limiting the creation of ‘unfit’ families. This included prohibiting so-called ‘mixed’ marriages between ‘Aryans’ and Jews and forcibly sterilising any Germans that were deemed ‘unfit’, including Jews, people who were considered to have physical or mental illnesses, and a broad swath of people deemed, for a variety of reasons, to fall within the category of ‘asocial’.Footnote 31

In Italy, the fascist government also emphasised the importance of women's roles as mothers, producing children for the fascist state. Anxieties about the declining birth rate in Italy became bound up with fears about the emancipation of women that were exacerbated by the shifting of gender roles during the First World War and continuing insecurities about the balance of power within the family that persisted after the war ended. The Italian fascist government implemented negative eugenic policies such as the criminalisation of abortion and banning of birth control, but did not rely on compulsory sterilisation as Germany did. It also ‘initiated positive measures, including family allocations, maternity insurance, birth and marriage loans, career preferment for fathers of big families, and special institutions established for infant and family health and welfare’.Footnote 32 Fascist officials, through these policies, not only attempted to redefine maternity but paternity as well, by encouraging both men and women to have children in order to create a family whose primary duty was service to the fascist state.Footnote 33

British feminists connected the fascist drive to increase the birth rate with fascist militarism. The pronatalist policies of Germany and Italy concerned feminists who worried that the growth of the population was being encouraged with the aim of eventually increasing the size of military forces in fascist countries. The feminist Cecily Hamilton, an active campaigner in several women's organisations, highlighted marriage loan programmes and childbirth bonuses as examples of how ‘the German Nazi, like the Italian Fascist, preaches the well-filled cradle and denounces the practice of birth-control’.Footnote 34 Hamilton noted that she herself was not concerned with any decrease in the number of large families, connecting population growth to war and expansionism among governments. She argued that it was clear that governments who were attempting to drive up the birth rate did so because they wanted to be successful in future wars, as ‘the race in armaments is not confined to battleships and guns and aircraft; there is also the race in human war material – and that begins in the nursery’.Footnote 35 Members of the Women's Co-operative Guild were also informed by their leadership that ‘women, under Fascism, have always been driven back to their own hearth, to bear children to be potential cannon fodder’.Footnote 36 Mary Stott, the editor of the Guild's periodical, Woman's Outlook, argued that this fact alone should be sufficient to prove how harmful fascism was for women. Both Hamilton and Stott pointed to connections between encouraging women to have children and preparations for future wars. While fascist governments claimed to honour motherhood, members of British women's organisations condemned the statements and policies of these states as anti-feminist, militaristic propaganda.

Members of the British women's movement worried not only that children would be brought up to be soldiers and lose their lives in military conflict, but also that they might be victims of war before they were even able to fight. Many in Britain were convinced the home front would be the main site of conflict in the next war, and thus worried about what they saw as the inevitable victimisation of women and children in such a war.Footnote 37 In particular, feminists feared that the home would become a site of destruction with both sides in any conflict willing to target civilians in bombing campaigns.Footnote 38 Many women's organisations also advocated against instituting air-raid precautions as they believed no protection would be adequate, particularly after Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin's famous statement in the House of Commons that ‘the bomber will always get through’.Footnote 39 Feminist campaigns against aerial warfare often revealed activists’ anxiety, mirrored by the general public, about the potential vulnerability of women and children in wars.Footnote 40 As historian Susan Grayzel has argued, because aerial warfare shattered the gendered separation of the ‘home front’ and the ‘war front’ as civilians became targets of bombing raids, gender was central to the way British citizens imagined this type of warfare, with women and children emphasised as the likely victims of an aerial attack.Footnote 41

This fear was made a reality in 1935. In October of that year, after months marked by border skirmishes and Ethiopian appeals for a League of Nations intervention, fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia, known as Abyssinia, relying heavily on aerial bombing. From the beginning of the conflict, the Italian Air Force, the Regia Aeronautica, bombed Ethiopian cities and towns, purposefully targeting the civilian population.Footnote 42 This instance of fascist aggression confirmed the beliefs of the members of British women's organisations, as aerial bombing was being used in war and it was being used to specifically target civilians. The conflict drew the protests of many British women's organisations, who added to Ethiopian calls for League intervention and supported Ethiopia's independence.Footnote 43 In addition to bombing Ethiopian civilians, the Italian Air Force also provided aerial support to Italian ground troops, bombed Red Cross hospitals and ambulances and deployed chemical weapons during the conflict.Footnote 44 Mussolini himself approved the use of mustard gas, fully disregarding international agreements, such as the Geneva Protocol, that prohibited its use and the targeting of civilians.Footnote 45

Members of the Ethiopian royal family appealed specifically to women abroad to aid the civilisations who were targeted by these Italian attacks. After an appeal from the Empress Menen Asfaw in the months leading up to the invasion, both the Women's International League and the Women's World Committee Against War and Fascism announced plans to use airplanes to provide aid to the women in Ethiopia who had suffered from bombing raids in the winter of 1935.Footnote 46 The seventeen-year-old daughter of the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, Princess Tsehai, also appealed specifically to women to come to the aid of Ethiopia as civilians suffered from aerial attacks and chemical weapons.Footnote 47 Addressing a room of foreign press correspondents in April of 1936, Princess Tsehai appealed to the women of the world to take action on behalf of Ethiopia.Footnote 48 She called on women to pressure the League of Nations, their governments and ambassadors ‘to drive off this common danger to humanity, this agony, this death by bomb, shell, and gas, before it again establishes itself as it is doing here now, soon to spread fatally to your homes and your menfolk too’.Footnote 49 The princess's appeal rested on the same assumptions as those of British feminists, who argued that women, as mothers and as potential civilian victims, more fully understood the cost of war, and therefore they could be stronger opponents of it.

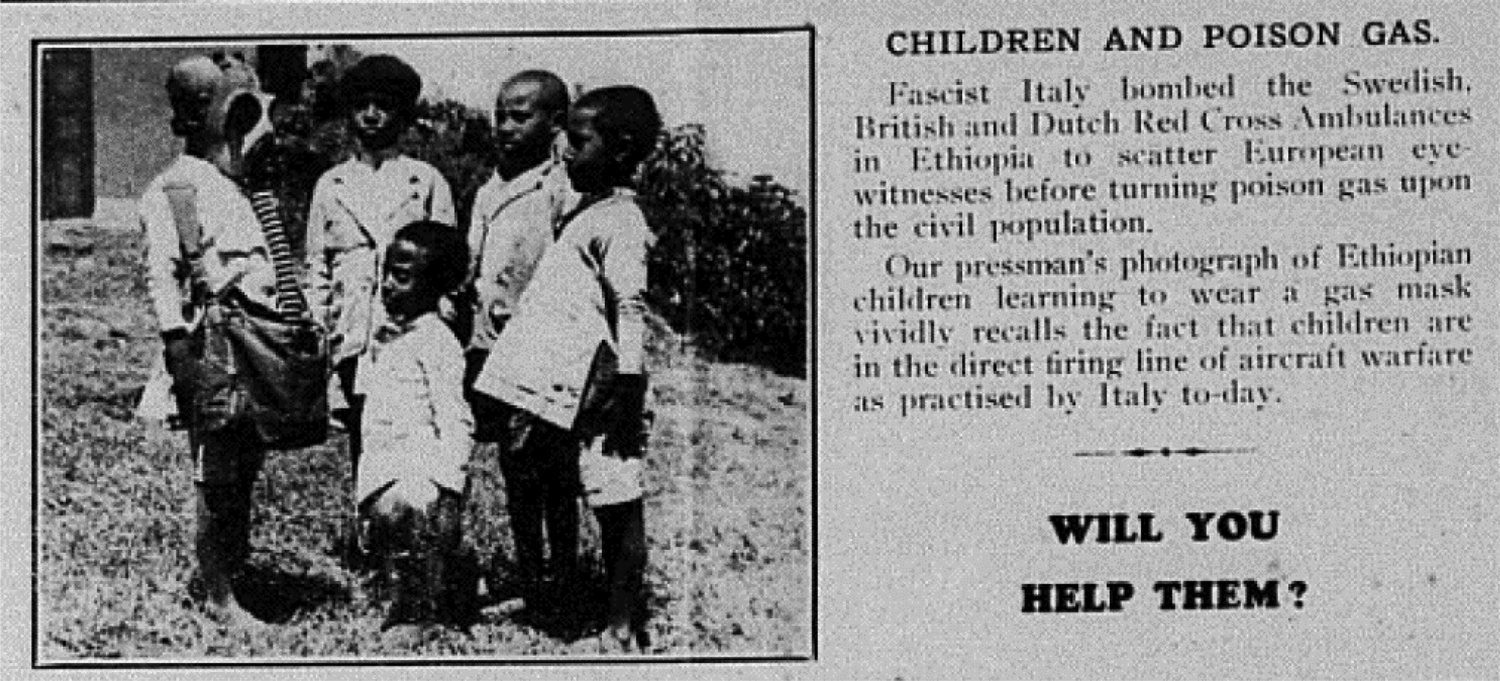

Princess Tsehai's message was not lost on those British feminists who opposed fascism and war. The British feminist, and former suffragist, Sylvia Pankhurst admired Princess Tsehai's work. Pankhurst became increasingly concerned about the looming threat of fascism, both to the independence of Ethiopia and women's rights, causes she supported until her death in Addis Ababa in 1960. In order to promote her ideas, she established a newspaper dedicated to the cause of Ethiopian independence, New Times and Ethiopia News, in 1936. Pankhurst interviewed the princess for her periodical after the princess and her father fled the conflict in Ethiopia.Footnote 50 In the interview, Pankhurst apologised for the little that had been done to aid Ethiopia, remarking that the princess had appealed to Englishwomen for aid on more than one occasion.Footnote 51 In reply, the princess gave Pankhurst another message, this time to the women of Europe, expressing her hope that ‘wives and mothers of other nations will never have to endure the torture of the Ethiopian women, who have been called upon to nurse the wounded and the horribly burned bodies of the soldiers who dared the gas attacks of the enemy’.Footnote 52 Princess Tsehai recounted the suffering that she witnessed during the conflict in order to convince women, particularly those in Britain, to press for an end to the war and the reestablishment of an independent Ethiopia.Footnote 53 At a London meeting in June 1936, she told of the suffering that the women of her country endured, and thanked the members of the Women's Peace Crusade for their work on behalf of Ethiopia while expressing her support for the crusade and other women's organisations.Footnote 54 Princess Tsehai's descriptions of the suffering of Ethiopia caused by aerial warfare was echoed by her father when the emperor addressed the League of Nations in 1936, describing in vivid detail how the entire population, including women and children, were at risk of death and destruction caused by Italian bombs and chemical weapons.Footnote 55 Pankhurst amplified this message in her paper New Times and Ethiopia News, featuring photos that depicted Ethiopian children who would be victims of future aerial attacks (figure 1).Footnote 56

Figure 1. Children and poison gas. New Times and Ethiopia News, 9 May 1936.

Confirmation that women and children would be civilian victims of fascist warfare came again after Italy and Germany ignored the pledge they had made to refrain from intervening in the Spanish Civil War, instead aiding Francisco Franco's nationalist rebels through bombing campaigns beginning in 1936. A few months after Mussolini and Hitler had independently agreed to give air support to Franco's troops, fascist bombers launched an assault on Madrid.Footnote 57 British women's organisations were horrified when they learned of the fascist bombing of Guernica in April of 1937.Footnote 58 The city had been intentionally targeted, not for tactical military reasons but in an attempt to terrorise and subdue the Basque population.Footnote 59

Criticism of aerial warfare by British women's organisations only increased after these attacks on civilians in Spain were publicised by press accounts highlighting the loss of life of women and children.Footnote 60 Virginia Woolf addressed the photos contained in these press accounts in Three Guineas, stating that ‘they are not pleasant photographs to look upon . . . This morning's collection contains the photograph of what might be a man's body, or a woman's; it is so mutilated that it might, on the other hand, be the body of a pig. But those certainly are dead children’.Footnote 61 The bombing of Guernica in particular was widely condemned and led to renewed discussions about air disarmament.Footnote 62 Appeals for Spanish relief also emphasised the suffering of women and children caused by aerial warfare. Photos of suffering children were used in articles to encourage women to donate to Spanish aid campaigns. Three Spanish children looked directly into the camera in a photo printed alongside an article appealing on behalf of refugees in Woman's Outlook, the periodical of the Women's Co-operative Guild. The caption read: ‘some of the homeless Spanish children whose pathetic appeal must surely touch the hearts of all mothers’.Footnote 63 Children were a particular target of relief and nearly 2,000 Basque children were evacuated to Britain during the conflict.Footnote 64 As occurred in the case of Ethiopia, the conflict in Spain prompted British women's organisations to protest fascist militarism and war and call on other women, as mothers, to similarly condemn fascist bombing and the victimisation of children in Spain. As the work of Emily Mason has demonstrated, for some activists, including Florence Ranson, the bombings in Spain were also influential in their decision to support intervention in Spain, including the British government sending weapons to the Spanish Republic, when they had previously supported non-intervention.Footnote 65

Parliament and Population Decline

In their attempts to highlight the gendered threat of war, feminists also connected population decline in Britain to women's desire to limit their fertility for fear of impending conflict. Helena Swanwick chided government ministers alarmed at the falling birth rate for not connecting women's unwillingness to have children to mothers’ fear of raising and losing their children during a war.Footnote 66 These same arguments were made during debates about population decline in parliament in 1937. Conservative, Labour and Liberal MPs all expressed concern about the documented fall in the birth rate and women's use of birth control, though they offered different analyses of why the decline was occurring. Labour MPs were more likely to point to the threat of war and economic insecurity as root causes, arguing that mothers did not want to produce ‘cannon fodder’ for the next war.Footnote 67 Some Conservative MPs, on the other hand, viewed women's increased rights and access to birth control as a major contributing factor to the decline. In proposing the resolution, Major John Ronald Cartland argued that this was cause for alarm, as the decline ‘may well constitute a danger to the maintenance of the British Empire and to the economic well-being of the nation’.Footnote 68 Other Conservative MPs, such as Duncan Sandys and Richard Pilkington, also expressed concern about the population decline because they viewed it as a threat to the empire.Footnote 69 Pilkington, in particular, feared that the West would be eclipsed by the East if the trend in population decline continued, and posited that the decline might be ‘caused by women going into public life – lambs straying out into the jungle’.Footnote 70 Whether concerned about the viability of the empire or economic insecurity and the threat of war, these men overwhelmingly agreed that there was indeed a population problem.Footnote 71

It was not lost on the MPs who took part in this debate that all of the speakers on the subject were men, and many of them bachelors.Footnote 72 In seconding the motion, Sandys noted that the MP who proposed the motion, Cartland, ‘is a bachelor and is not in a particularly strong position to preach on this subject’, but also stated that ‘the House is indebted to him for having raised this very important topic at this critical moment in the history of our population’.Footnote 73 Speaking at an international conference a few years earlier, a member of the Women's Co-operative Guild had argued that it was a matter of great concern that decisions about war and peace were being made by men without children. Mrs. Elliott, serving as a delegate for England, called into question the masculinity of German leaders who restricted women's rights, stating that ‘German women have been robbed of their liberty by the Chancellor, who is a bachelor, and whose right-hand men are Herr Goebbels, a cripple, and Herr Goering, a divorced man refused the custody of his children. This triumvirate of incomplete manhood has determined that the fate of women should be the recreation of the tired warrior’.Footnote 74 Elliott argued that it was mothers, not bachelors, who were worried that their children would be cannon fodder in a coming war. Consequently, mothers would be able to most effectively work for peace.

A few months after the initial Commons debate about the population problem, the Population (Statistics) Bill was introduced by Sir Kingsley Wood, the Minister of Health, with the purpose of obtaining more information about birth rates and other figures related to population in Britain.Footnote 75 At the bill's second reading, MPs continued to speculate about the causes of the population decline in addition to discussing the content of the bill itself. Again, Labour MPs voiced concerns that women's fears that their children would be cannon fodder in future wars, or have to fight to defend the empire, were impacting the birth rate.Footnote 76 Though the Minister of Health asserted there was no statistical basis from which to make that claim, Labour MPs still argued that this was a significant factor in causing the decline.Footnote 77 Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, a Labour MP well-known for his participation in the women's suffrage movement, argued that women's demands for peace, economic security and lower rates of infant mortality needed to be met before they would be willing to have children, noting that ‘women now have it in their power to limit population – and are so limiting it’.Footnote 78 As in the first debate, Conservative MP Richard Pilkington made xenophobic comments based on his fear that the empire would lose strength if whites were no longer the majority, and expressed his admiration for the dictatorial regimes in Italy and Germany for taking immediate steps to encourage a growth in the birth rate in their own countries.Footnote 79

In perhaps the most memorable moment of the debate, A.P. Herbert, an Independent MP for Oxford University, read out a memorandum in verse to answer the question ‘why are more babies not being born?'.Footnote 80 He cited a variety of causes, ranging from the rising cost of education and inadequate housing, to streets overcrowded with cars. The memorandum concluded with a poignant gesture toward fears about war and the militaristic education of youth:

Abroad, to show that everyone was passionate for peace,

All children under seven joined the army or police;

The babies studied musketry while mother filled a shell –

And everybody wondered why the population fell.

The world, in short, which never was extravagantly sane,

Developed all the signs of inflammation of the brain;

The past was not encouraging, the future none could tell,

But the Minister still wondered why the population fell.Footnote 81

Sylvia Pankhurst, applauded the statements of Herbert, and wrote another stanza that she argued could have fittingly been added to his:

And every tender little babe that lightly draws its breath

Was menaced in its cradle by the awful ‘birds of death’;

And many a gentle woman vowed: ‘to die in this mad hell

I'll never bear a child’! – and so the population fell.Footnote 82

Pankhurst highlighted women's ability to access birth control and limit their own reproduction if they felt that their government was not adequately guaranteeing their well-being, safety and security.

Marriage Bars and Birth Strikes

These debates about population decline were not unique to Britain, and as was the case with Sylvia Pankhurst, other feminists paid close attention to how government representatives were discussing the birth rate in the late 1930s as war loomed nearer. Some feminists were concerned not only about the broader implications of British debates about population decline but also fascist efforts to increase the birth rate in support of militarism. Responses of women's organisations to these issues were in large part determined by their own specific priorities as an organisation. For instance, as a pacifist organisation of working-class housewives, the Women's Co-operative Guild argued for a birth strike as a means for women to exercise control over their own reproduction and prevent a future war. The National Union of Women Teachers and the Open Door Council, both made up of primarily middle-class feminists committed to equality in women's employment, were particularly concerned that anxieties about population decline would lead to increased hostility toward married women workers, citing fascist countries as an example of how this could occur.

The argument that women should limit their own reproduction as a political act was not new but drew on a feminist tradition of women threatening ‘birth strikes’ when the government failed to honour its responsibilities to women citizens, denying them rights or social support. The birth strike was first proposed in France in the late 1800s, and was associated with neo-Malthusianism, syndicalism and later feminism. The notion of a birth strike was taken up again by German neo-Malthusian socialist physicians in 1913 but was disapproved of by Social Democratic women such as Clara Zetkin, who instead wanted to strengthen the movement by having more children, not fewer. Some in the British women's movement had also previously advocated for this type of strike action. In 1914 the feminist Women's Freedom League suggested using contraception as a non-violent means to pressure the government to give women the right to vote. In these calls for a birth strike, women were encouraged to use birth control in order to create better outcomes for the working class, stop producing human ‘cannon fodder’ for the next war, or force governments to give women political rights.Footnote 83

Feminist debates over reproduction, women's rights and fascism were widely reported in regional and national newspapers after a contentious exchange at the 1937 annual meeting of the National Council for Equal Citizenship in London. At the meeting of this feminist organisation, which had been a leader in the women's suffrage movement, Eva Hubback moved a resolution on behalf of the executive in support of family allowances as a means to check the population decline.Footnote 84 Support for family allowances was hotly contested by feminists in previous decades and this meeting was no exception.Footnote 85 Delegates protested this resolution, including the feminist barrister Helena Normanton, who argued that the provision would be in line with the pronatalist policies of Italy where children were viewed merely as ‘cannon fodder’. She had personally witnessed the military drilling of children in Italy, where boys of ten were given real machine guns to train with while boys as young as three were given toy guns. Normanton also described Italian schoolchildren's copybooks which contained lines such as ‘the wounded soldier is the true citizen of Italy’. Furthermore, she maintained that Hubback's resolution was just what the dictators wanted.Footnote 86 The press covered this debate widely and the story was picked up by regional as well as national papers.Footnote 87 Writing in the footnotes of Three Guineas, Virginia Woolf referenced the argument made by Normanton, and agreed that refusing to bear children was one way in which women could help prevent a future war. Woolf also cited examples of letters to the editor in which women made the case that the low birth rate was a result of women not wanting to have children due to the threat of war. Woolf herself argued that ‘the fact that the birth rate in the educated class is falling would seem to show that educated women are taking Mrs. Normanton's advice’.Footnote 88 Nevertheless, at this particular meeting, despite Normanton's protest, the resolution was passed twenty-nine votes to twelve.Footnote 89

In at least one aspect, Normanton's assessment at the 1937 meeting was correct. There were feminists such as Hubback who, like the dictators of Germany and Italy, supported eugenics in order to increase the birth rate and counter population decline. Hubback's support for eugenics, however, should not be viewed as an indication of her support for fascism. As was the case with many feminists drawn to eugenics during the interwar period, Hubback supported ‘positive’ eugenic inducements such as family allowances but did not support the oppressive policies of fascist regimes, including their broad applications of compulsory sterilisation.Footnote 90 Furthermore, concern about the birth rate was shared not only by fascist governments but also by a majority of European states in the interwar period, as the debate over population in the British press and parliament demonstrates. Hubback's support for family allowances was motivated both by her desire that mothers and children be adequately provided for and by her eugenic concerns about population decline.Footnote 91 Hubback urged women to ‘work for the preservation and welfare of our racial stocks’, while also arguing that women should work for peace in response to the threat of war by fascist powers.Footnote 92

Shortly after the debate, the Daily Herald published an article written by Normanton in which she rearticulated her stance that policies intended to drive up the birth rate had to be viewed in the context of war and militarism. She argued that if one country effectively drove up their birth rate, which the fascist dictators were attempting to do through ‘marriage subsides, free furniture and family allowances’ in Germany and ‘family allowances, of all kinds of beneficent distributions at the local Fascio, donations to fathers of large families, medals and prestige by the cartload for wholesale progenitors’ in Italy, it would create a competition between countries to produce more babies, essentially an arms race of human war material.Footnote 93 Normanton called on mothers to respond to calls to drive up the birth rate by making it clear that they would not have more children to fight a war or maintain an empire. Policy makers would be forced to reconsider their armaments spending, she contended, if women said ‘so long as you keep this country actually and prospectively in peace, I will endeavor to bear a child every two or three years until I have four or five, and as soon as the skies darken with war clouds I shall bear no more until the skies are clear again’.Footnote 94 The feminist and pacifist writer Vera Brittain strongly agreed with the sentiments expressed by Normanton, and in a letter to the editor to the Daily Herald stated that ‘had I faced the choice of having children after, instead of before 1931, I doubt if my son and daughter would have been born. Under present conditions I would not voluntarily give life to another human being’.Footnote 95 While anxieties about population decline were not new in the 1930s, by the late 1930s, when these debates gained even more prominence in Britain, the looming threat of war and emphasis on maternity caused many feminists such as Normanton and Brittain to call on women to refuse motherhood as a means to prevent another war.

Normanton's position was also supported by other feminist organisations such as the National Union of Women Teachers and the Open Door Council, an organisation that NUWT members had taken a leading role in establishing.Footnote 96 As previously discussed, the NUWT was committed to peace work throughout the interwar period, but was also concerned that the government's anxieties about the birth rate would be harmful to women beyond fuelling the drive for military conflict. After hearing Sir Kingsley Wood's speech in parliament, in which he stated that further enquiry would be made into whether there was any connection between low birth rates and high rates of women's employment, Muriel Pierotti, a member and Assistant Secretary of the NUWT, expressed concern that such sentiments might lead to renewed attacks on the right of married women to work.Footnote 97 In the years after the First World War, restrictions on women's work, including marriage bars, the requirement that women leave their jobs once married, were reinstated after being temporarily lifted during the war.Footnote 98 The NUWT, along with other feminist organisations, protested these policies that often affected women teachers in particular as many local authorities had enacted marriage bars against women in the teaching profession.Footnote 99 As early as 1933, the NUWT argued that the ‘spirit of fascism’ was behind these measures not only in Germany and Italy, but in Britain as well.Footnote 100

As the population debate gained prominence through parliamentary debates and well-publicised disputes such as that between Normanton and Hubback, the NUWT called on its members to recognise the importance of the issue, which was also taken up by the Open Door Council. According to Florence Key, who served as editor of the NUWT periodical, The Woman Teacher, beginning in 1937, ‘the question of population and the falling birth rate is one which must be carefully studied and watched by all feminists and lovers of liberty’.Footnote 101 Despite her advocacy for policies that differed from those supported by Hubback, Key also utilised the language of eugenics in order to advocate for women's rights in her role as Chairman of the Open Door Council, arguing that forcing women to confine themselves to a domestic role ‘is not self-sacrifice – it is race suicide’.Footnote 102 Similarly to the NUWT, the Open Door Council expressed concern that the focus on increasing birth rates led the public to ‘treat women as a means to an end’, without respecting them as human beings, and demand that they return to the home to give birth to children rather than engage in paid employment.Footnote 103 Hubback, Normanton and Key all agreed that women should work for peace and identified fascism as the greatest threat to that peace. But connections to other perceived fascist policies, in this case the stimulation of the birth rate and eugenics, caused some feminists to view the maternalist arguments of their colleagues with scepticism. Others tried to co-opt eugenics rhetoric in order to support their advocacy for women's rights, including the rights of married women to engage in paid employment.

Fascist pronatalist policies that valued ‘racially pure’ women almost exclusively as mothers heightened feminist concerns that women could be defined by their reproductive capacity, while also having no control over their bodies. According to the Women's Co-operative Guild, the Nazi government was misleading the German people with its emphasis on honouring and strengthening the family. Women in Germany were ‘being relegated en masse to a position which definitely belongs to the last century’.Footnote 104 Women were not respected as mothers but instead were being used to bear children in service to the Fatherland. Mothers had little say in the education of their children, with their influence being largely supplanted by party organisations that glorified war and military sacrifice. Members of the Women's Co-operative Guild recognised the importance of highlighting that their own emphasis on women's roles as mothers had little in common with fascist ideals. The ultimate goal of the Women's Co-operative Guild was to ensure peace while fascist governments were exploiting mothers in the service of war preparations.

In a series of editorials about the falling birth rate written for the Guild, Mary Stott contended that the so-called ‘population problem’ was not due to women's emancipation or growing knowledge about birth control. Instead, Stott maintained, ‘the strike against motherhood – for that is what the falling birth-rate really is – is due far more than we know to fears for the child's future. What incentive is there to bring a child into this ghastly world’?Footnote 105 Addressing women's concerns about economic hardship and war, Stott argued, would counter the decline in the birth rate. In another editorial she rejected the argument of dictators who were concerned about ‘falling birthrates because they want an endlessly growing supply of cannon fodder for their armies’.Footnote 106 Instead of pushing women to have children who would grow up in a world full of military conflict and poverty, she called for the government of Britain to ‘give our people real security; show that child-bearing really is the honour that we always say it is’ by ensuring economic security and, crucially, peace.Footnote 107 In her 1939 presidential address to the National Union of Women Teachers, Nan McMillan argued that it was more necessary than ever to work for feminism and peace as German women were being told that ‘there is no higher or finer privilege for a woman than that of sending her children to war’, and pledged to ‘resist with all our power this crude, barbarous, and mediaeval doctrine’.Footnote 108 According to these activists, fascist regimes offered a false glorification of motherhood; women were being used to build armies for war instead of for peace.

The notion that women's reproductive roles as mothers could help lead to war challenged the idea long promoted by pacifist women in the first decades of the twentieth century that women's roles as mothers would only strengthen and further their work for peace. Italy and Germany promoted, and understood the purpose of, motherhood in an altogether different way than the members of British women's organisations such as the Women's Co-operative Guild and the National Union of Women Teachers. These feminists understood the policies enacted by these governments as reducing women to their reproductive function in service of militarism rather than peace, and therefore worked to counter the fascist pronatalist policies that failed to combat what they viewed as the real cause of population decline. They demanded that their government provide physical and economic security for women so that they could be certain that their children would not be sacrificed as ‘cannon fodder’ in the next war. This was already occurring in fascist countries, and if the same were to hold true in Britain, then women would have no choice but to refuse to bring children into the world. Motherhood, these women argued, should be a force for peace, not war.

The notion that women were natural pacifists and anti-fascists was a sentiment shared by many within the British women's movement. Many activists stressed that fascist governments did not respect women's rights and enacted policies that harmed women and children rather than helped them, and therefore women would be most able to recognise these injustices. Influenced by the international women's movement, however, members of some British women's organisations also believed that by refusing to fulfil women's biological roles as mothers, they could oppose fascist militarism abroad and lack of security for women at home. Throughout the 1930s, members of the British women's movement continued to see women's social and biological identities as a basis from which to advocate for women's rights, at the same time that they understood fascist governments to be using these identities to oppress women. Feminist organisations and their members could have rejected feminist politics focused on women's reproduction and discourses of motherhood in light of the prescriptive and limited roles fascist governments proposed for women which often stressed women's duty to bear children in service to the fascist state. Instead, in their efforts to reshape the debate surrounding population decline, some British feminists used the language of maternalism, in this case arguing that women had the right to refuse to bear children, to continue to advocate for women's role in politics and oppose fascism and militarism, right up until the war against the fascist powers began.