Policy Significance Statement

The present paper, by analyzing the information architecture of the Brazilian National Civil Identification System (ICN) through a data protection and data justice perspective, aims to assist policymakers from Brazil to think of ways and solutions to avoid possible violations of data subjects’ rights, which arise from the implementation of a country-wide unified identification system. To this end, the discussions around the information architecture have the intention to highlight some aspects of the ICN that can be considered as vulnerabilities capable of potentially compromising the data protection ecosystem that has been built in the last few years. The ICN, in its turn, materializes long-lasting efforts from the Brazilian State to implement a public policy of unifying citizens’ identification.

1. Introduction

The present paper is part of a broader research agenda developed by Data Privacy Brasil Research Association, an NGO based in Brazil dedicated to conducting public interest research on the intersection of personal data protection, technology, and fundamental rights. Considering the current context of intense digitization of governments and the global movement toward national digital identity systems, in this study we try to analyze the deployment of a Brazilian national identity system through a privacy and data protection approach.Footnote 1

For this paper, we have developed research that is predominantly descriptive and qualitative, aiming to provide a deeper and contextual analysis of the research object, taking into account all the complexities and multiple characteristics which constitute it (Groulx, Reference Groulx, Poupart, Deslauriers, Groulx, Laperrière, Mayer and Pires2008; Igreja, Reference Igreja and Machado2017), in order to answer the following question: is the Brazilian National Civil Identification System (Identificação Civil Nacional or ICN) framework adequate with the Brazilian data protection general legislation (LGPD) and its principles—especially regarding its information architecture?

We have chosen a qualitative approach, by first conducting a desk research,Footnote 2 to understand the state of the art related to national identity systems, digital identity, and data protection. Later, we analyzed legislation and official government documents, since documents represent one of the main sources for Law scholarships (Machado, Reference Machado and Machado2017), as an effort to reconstruct the process of normative development of the Brazilian National Identity System, focusing on its information architecture.

What the study has found is that there are several tensions between the National Identity System and the data protection rules and principles, and that, even though the intention of the digitization of government and the use of digital identity to access public services is one of inclusion, it could generate exclusion.

As the study shows, the structuring of the national identity system (Section 2) has been a long process, with efforts from different mandates of the federal government, but there is still no definitive system in place. In 2022, there was almost the simultaneous launch of two different national identity documents, one by the Superior Electoral Court and the other by the Federal Government, in a duplicity of initiatives with the same functionality, adding to inefficient government spending and public policies. Moreover, the structuring of the identity system has been led almost exclusively by the government, without meaningful civil society participation.

As for the information architecture of the identity system database, Sections 2.1–3.2 show how a large-scale personal database, composed of the fusion of other databases, with a centralized structure, presents risks in terms of data protection and privacy, such as possibilities of abusive secondary use of data, insecurity of data, and government surveillance. Section 3.3 highlights how the large volume of data, including sensitive data, should have triggered the elaboration of a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA), which has not been done, adding to the risk to the data subjects’ rights and liberties. It is also shown by the study, in Section 3.4, how the identity law has not foreseen how the data subject could exercise their data rights foreseen in the LGPD.

Furthermore, Sections 4 and 5 provide some context into the digital transformation of the Brazilian government to discuss the use of the ICN database to login in the gov.br, the website with access to government services from the federal government. It highlights how Brazil still has severe inequalities, specially related to race and gender, which are reflected on access to services, including digital services, and how those could influence in not having a functioning digital identity and thus not being able to access public services and policies through gov.br.

The study’s main contribution to the digital identity international literature is to analyze in an empirical manner the deployment of a digital identity system, with a focus on its implementation and use to access government services. Masiero and Bailur (Reference Masiero and Bailur2021) note that there is a dichotomy between the developmental potential asserted by the digital identity for development agenda, with powerful international supporters, such as the World Bank and its ID4D program (World Bank, 2021), and the injustices that emerge in practice, accentuating the need to frame digital identity as an object of research. This study is also a chance to reach public officials with a diagnostic of possible problems and foster change so that the digital identity initiative can be improved.

2. The Brazilian National Identity System: A Descriptive Timeline

There is an international movement toward country-national digital identity systems. Brazil is part of this movement, and it is possible to say that the recent efforts made by the Brazilian government to provide digital identity to all its citizens are related to previous efforts to modify and, consequently, unify the Brazilian civil identification system, considering that, historically, identification documents are issued individually by the 27 states of the Federation.

According to Kanashiro and Doneda (Reference Kanashiro and Doneda2012), the history of the adoption of a new ID card in Brazil is long. The first attempt to develop a new identity system starts with the provision of Law 9,454, enacted in 1997, which created the Civil Identity Registry (Registro de Identidade Civil or RIC) (Lei nº 9.454,1997). Although the provision of RIC dates back to the last years of the 20th century, its implementation only started almost 10 years later. Such a process began in 2004, when Brazil acquired the necessary equipment to digitize citizens’ biometric identification (Kanashiro and Doneda, Reference Kanashiro and Doneda2012).

The idea behind the institution of RIC was to establish a unique identification number for all Brazilians. That meant that this new document would merge several other documents that then served as proof of identity—and still do, nowadays. The merger would allow the unification of several databases into a unique one and that would reflect onto the issuing of one unique document as well (Kanashiro and Doneda, Reference Kanashiro and Doneda2012).

Despite the intention to implement RIC, its full deployment never happened, mainly because of the high costs involved in this process (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Doneda and Santos2016). In 2015, the federal government submitted to the Congress the draft bill n. 1,775, in an attempt to establish a new identification system that would revoke Law 9,454 and replace the unmaterialized RIC. This new system was called National Civil Registry (Registro Civil Nacional or RCN), and it was later converted into the Identificação Civil Nacional (National Civil Identification or ICN—the current effort from the Brazilian federal government to implement a unique identity system in the country. With the RCN’s draft bill, Brazil had a first glimpse on what the ICN would be, since the information architecture idealized for the former would be replicated, in part, to the latter’s structure.

During the aforementioned draft bill discussion process, several public hearings were held by the Chamber of Deputies. The public participation in those hearings was very homogeneous, if we consider that almost all of the participants were linked to the public sector—most of them representatives of the Legislative Branch. Civil society’s participation in these debates was not expressive, as only one civil society representative spoke during the course of all public hearings (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Luciano and Santos2017). As a result of these forums, a substitutive draft bill was proposed, altering some aspects of the digital identity system’s structure and its name. The substitutive bill was later approved by the Chamber of Deputies and then submitted to the Senate, where it was also quickly approved.

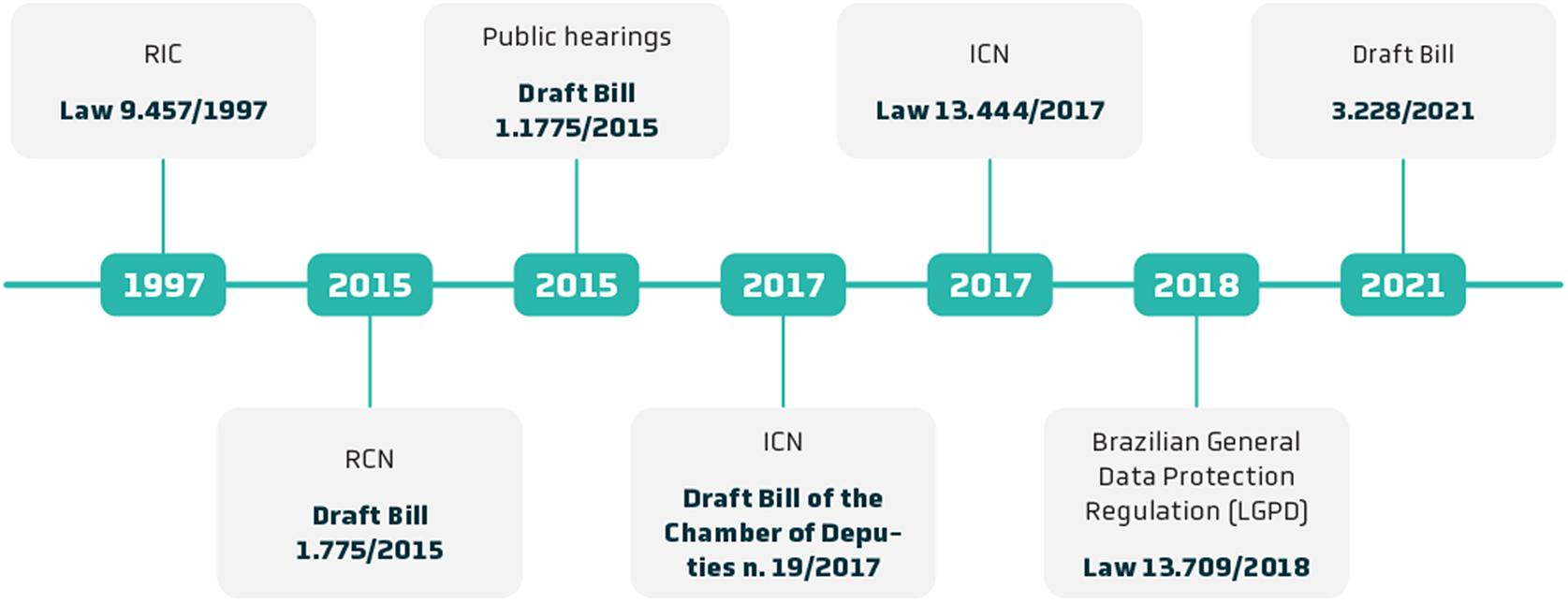

This process led to the approval and enactment of Law 13,444 from 2017, which provides for the institution of the National Civil Identification (Lei nº 13.444, 2017). The system was created by a joint effort of the Brazilian federal government and Superior Electoral Court (TSE), both of which were responsible for the draft bill that created the ICN. The purpose of the national identity document remained the same: the twofold goal of its institution is to provide for each citizen a national unique identity number, at the same time that the national identity document will carry other official information from other governmental identity documents (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Brazilian initiatives of implementing a national identity system throughout the years.

All of the main marks involved in the attempt of implementing a national digital identity in Brazil can be seen in the following timeline.

Up until March 2022, the ICN is still not fully implemented, but its implementation is on course. At the moment, the primary use of the ICN database is related to the “gov.br” platformFootnote 3—the Brazilian federal government’s initiative for hosting and offering online public services. Such use results from a technical cooperation agreement signed in March 2021 between the Superior Electoral Court and the Federal Executive Branch—represented by the Ministry of Economy and the General Secretariat of the Presidency of the Republic (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, 2021a). The agreement foresees that the ICN database is used as the preferred means of authentication of users of digital public services (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, 2021a), in an attempt to strengthen the National Civil Identity System.

The aforementioned outcomes and the way that the ICN was idealized in a different government, but still with similarities with the previous project, RIC, show that the National Civil Identification System is, in fact, a State—rather than a specific government—policy. That is, the effort of implementing a national identity system in Brazil is long dated and involved several public actors, meaning that it results in a policy that is not relatable to one government in specific, but as one that was conducted throughout several governments and was incorporated as a Brazilian State’s priority.

In more recent developments, in February 2022, the Superior Electoral Court launched a new implementation stage of the National Identity Document, originated from the ICN law, that will begin to be issued to members of the electoral court in March 2022, and for citizens of the State of Minas Gerais in August 2022. It is the expectation of the Superior Electoral Court that the document will be available to be issued for the entire population from February 2023 onwards (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, 2022). However, in the same month of the Superior Electoral Court’s launch, in which the Federal Government participated, as it is a partner in the ICN initiative, the Federal Government launched its own National Identity Document, following a presidential decree n. 10,977, from February 23 (Decreto 10.997, 2022). Both documents are National Identity Documents, meant to be unique to solve the problem of the multiplicity of documents of identification, to carry the different identification information of citizens in only one document, and to have a digital form, as well as to be used at the gov.br. Functionally, they are essentially the same. The duplicity of initiatives adds to the already complicated identification scenario in Brazil, since it does not solve the problem of having a unique national identity and might add to inefficient government spending and public policies, considering they are functionally the same.

2.1. The Brazilian National Civil Identification: information architecture

Once we understood how and why we have come to the enactment of the ICN, it is relevant to understand its information architecture to comprehend, further, how it relates to data protection issues.

The ICN Law establishes a unique database, which was formed by the concentration of a series of other databases from different government entities and levels, each of them with a different function. As can be visualized in the following image, the before existing databases that were merged in order to now compose the ICN database are the National Civil Register System (Sistema Nacional de Informações de Registro Civil), controlled by the federal government; the National Civil Register Record (Central Nacional de Informações do Registro Civil), controlled by the National Council of Justice; the biometric database from the Superior Electoral Court, as well as other data from the electoral justice, all controlled by the Superior Electoral Court; the Database from the State Identity Institutes; and the National Identity Database, from the Federal Police (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Brazilian National Identity System (ICN) information architecture.

In the matter of access to the ICN’s database, the law allows it for both the Executive and Legislative powers of any of the federative units (federal, state, or municipal levels), except for the electoral data, which is only accessible to the electoral justice. The ICN Law, however, does not establish any procedure for such access. In other words, except for the electoral data, the law does not foresee specific procedures or restrictions for public bodies from the Executive or Legislative power to access the citizen’s data from the database. In this sense, there is a potential violation of the principles of purpose and necessity, both established by the Brazilian General Data Protection Law (LGPD) in its article 6 (Lei nº 13.709, 2018), considering that the absence of a clear access procedure may lead to secondary use of the ICN database that is not compatible with its primary purpose. This point will be further deeply discussed.

The ICN Law also foresees the possibility that the Superior Electoral Court offers identity authentication services to private entities using the biometric data from its database. Such services could imply secondary use of the database related to economic advantage, which can be submitted to further regulation of the Brazilian National Data Protection Authority, according to article 11, paragraph 3 of the LGPD (Lei nº 13.709, 2018). In 2021, the Federal Government signed two agreements to provide, free of charge, to banks, an experimental period of authentication services using the ICN database. Those agreements were brought to public attention in January 2022, and after outcry from the public and civil society, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office has launched an investigation into those agreements (Partido dos Trabalhadores, 2022). The use of a public database for the advantage of private actors might represent a deviation from the public interest that justifies the treatment of citizen’s data.

Furthermore, regarding the governance structure of the ICN, it deserves to be highlighted that its database is managed by the Superior Electoral Court, with no prior legal or structural adjustments to the Court as to execute this task that is different from its core activities, related to the elections. This atypical participation of an electoral justice institution in a civil register identity system was justified by the fact that it already possessed an extensive biometric database for the elections (Poder Executivo, 2015). Yet, it is a peculiarity.

In terms of governance arrangements of the National Civil Identity System, the ICN Law creates a Steering Committee (Comitê Gestor da Identificação Civil Nacional or CGICN) to recommend the ICN biometric data patterns and establish guidelines on the implementation of the Executive and Judicial Branches systems’ interoperability, among other competencies. According to the ICN Law provisions, the CGICN is composed of nine members, all representatives from the public sector, representing the Federal Executive Branch, the Superior Electoral Court, the Chamber of Deputies, the Federal Senate, and the National Justice Council.

2.2. Draft bill n. 3228, 2021Footnote 4

On September 20th, 2021, a draft bill was presented to the Congress by the federal government to amend the ICN Law. According to the federal government, the proposed alterations intend to amplify the integration between the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial powers; to accelerate the project to safely and digitally identify all Brazilians; to create more options of partnerships between public and private entities regarding civil identification and authentication; to ensure the participation of representatives of the federative states in the composition of the ICN Steering Committee; and to facilitate the operationalization of the ICN fund, ensuring the financial viability of the policy (Projeto de Lei nº 3.228, 2021).

The most significant changes for the object of this paper proposed by the draft bill to the ICN Law intend to alter its articles 2 and 3, allowing the ICN database to be replicated in the computer system of the Federal Executive Branch, and integrated into the database of the Executive Branch of other government levels, including biometric data, as long as there is a legal agreement authorizing it. The draft bill also proposes an alteration of the ICN Law that would allow for the Superior Electoral Court to establish agreements, contracts, partnerships, or instruments alike with private entities for the maintenance of the ICN database, as well as to provide to private parties verification services involving biometric data.

The way it is proposed, however, the draft bill adds to the risk of secondary use of data with purpose deviation, as it facilitates the sharing of data from the ICN database to the Executive Branch of other government levels, including biometric data. It also allows for private entities to be responsible for maintaining the ICN database, which in practice allows private parties to access extensive public databases. Allowing for the databases to be copied and incorporated makes it hard for the ICN Steering Committee and the Superior Electoral Court to remain responsible for the data in the provided copy of the database that can be shared as the new controllers think is best.

In addition, the draft bill’s provisions alter the ICN’s information architecture in a way that can compromise the security of the data that composes the ICN database, since none of the proposed changes of the draft bill mention data protection guarantees or institutes. This scenario thus reinforces the goal of this study and shows the relevance of analyzing the Brazilian National Civil Identity System from a data protection perspective. The possible tensions between the draft bill and the data protection legislation will be further addressed in the next section.

3. Data Protection in the Brazilian National Identity System

After explaining the information architecture arrangement provided by the ICN Law, as well as the alterations the federal government’s draft bill intends to make in it, this section will be dedicated to the core analysis of this paper: the adequacy of the ICN structure with data protection principles from the Brazilian General Data Protection Law (LGPD) and rules.

The key concerns regarding the ICN architecture that will be analyzed in this section are the transferring of data between public administration bodies, the centralization of databases, the large use of sensitive data, and the lack of publicity of data processing and exercise of data rights.

Before that, it is important to stress that discussions concerning data protection are more recent in Brazil than in most countries in the European Union, for example. The debates regarding the creation of a Brazilian General Data Protection Regulation started in 2010, but the Law was only approved in 2018, after intense political disputes—and after the approval of the ICN Law—coming into force in September 2020. The National Data Protection AuthorityFootnote 5 was established in November 2020 and the administrative sanctions established by the LGPD came into force even later, on August 1st, 2021.Footnote 6

It is worth noting, however, that before the approval of the Brazilian General Data Protection Law, there were sectoral laws already in force that contained data protection rights, such as the Consumer Protection Code (Código de Defesa do Consumidor, from 1990) and the Internet Civil Rights Framework (Marco Civil da Internet, from 2014).

3.1 Transferring of data between public administration bodies: informational separation of powers

The Brazilian LGPD foresees two situations in which personal data can be processed by the government: (a) for the execution of public policies (articles 7 and 11) and (b) for the fulfillment of institutional attributions (article 23) (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2019). However, the law does not define clear cut criteria for the sharing and secondary use of personal data among public bodies, indicating only that it has to be related to the specific purposes of execution of public policies and legal attributions by agencies and public entities (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2021):

Art. 26. The shared use of personal data by public authorities shall fulfill the specific purposes of execution of public policies and legal attributions by agencies and public entities, subject to the principles of personal data protection listed in Art. 6 of this Law. (free translation)

The debate of sharing and secondary use of personal data among public bodies is directly related to informational self-determination and purpose limitation (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2021).

Information self-determination is a founding principle of the LGPD. Originated from the German Constitutional Court debate, it indicates that for an individual to develop their personality freely, there should be restraints to the sharing of their personal data (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2021). In that sense, the interpretation of the possibility of sharing and secondary use of personal data among public bodies is to verify if there is compatibility between the initial purpose of the collection of the data and the purpose for which the data are being shared. The sharing of the data should only be possible if there is such compatibility for their secondary useFootnote 7 (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2021).

Simitis (Reference Simitis1987, p. 737) considers that one of the four basic elements of any data processing regulation is that “requests for personal information must specify the purpose for which the data will be used, thereby excluding all attempts at multifunctional processing.” The author highlights that purpose specification is a normative barrier to the technical possibility of multifunctional use of the data, which can be considered by public and private organizations as a decisive advantage of automated processing. Simitis (Reference Simitis1987) goes further into explaining that such a limitation (purpose-bound processing) has effects beyond the processing of data, including organizational consequences. When it comes to government bodies treating personal data, the author specifies:

Consequently, government in particular no longer can be treated as a single information unit, justifying a free flow of data among all governmental units. An agency’s specific functions and their relationship to the particular purpose that led to the collection of the data determine the access to the information, not the mere fact that the agency is part of the government. The internal structure of government, therefore, must be reshaped to meet the demands of functional separation that inhibits proliferation tendencies (Simitis, Reference Simitis1987, p. 741).

What Simitis (Reference Simitis1987) is proposing is the informational separation of powers, if that idea is followed, what determines an agency or government entity access to data is not the fact that they are part of the state, but the specific function of the agency or government entity itself, and the relation of that function with the purpose of the data collection.

The Brazilian Supreme Court judgment recently in a preliminary injunction incorporated the theory of the informational separation of powers. In the case “ADPF 695,” the court’s Minister explicitly stated the inexistence of a general permission to the sharing and free flow of data among government bodies, recognizing that the State is not a single unity of information. The case discusses a decree that allows the sharing of data between organs and entities of the federal executive power without the need of a previous agreement, and the specific determination that the National Department of Traffic, which holds the database of drivers licenses, shared its database with the Brazilian National Agency of Intelligence. The decree also creates a Citizen’s Base Registry (Cadastro Base Cidadão). It is important to note that in the language of the decree, the first goal of the establishment of such a database is to “simplify the offer of public services.”Footnote 8 Article 5 of the decree allows the sharing of data among organs and entities of the government without any previous legal agreement, as long as it aims to fulfill the goals established in the decree. Article 18 of the decree determines that the initial data on the Base Registry will be composed by citizens’ National Tax Number, full name, social name, birth date, sex, parents’ names, nationality, place of birth, death date, and date of the inscription or alteration of the National Tax information, that signals an incorporation of the informational separation of powers, as exposed by Simitis (Reference Simitis1987), by the court. Even though this is not the definitive rule, preliminary injunctions have considerable influence on the judgments of the lower courts.

As mentioned before, the ICN Law in its article 3 allows access to its database by the Executive and Legislative Branches of all federative levels (cities, states, or the federal government), which indicates a possible violation of the informational separation of powers. There is no specific procedure established in the Law for this access to ensure compliance with the principles and rules of data protection, specially the purpose limitation. One example is that in a hypothetical situation a mayor from a small city could demand the identification information from people from the capital without specifying why it needs this information. In other words, a closer analysis of the ICN Law’s arrangement on data access reveals a possible inadequacy with the principles of informational self-determination and purpose limitation, both of which are central in the Brazilian data protection law.

Moreover, the aforementioned draft bill 3,228, 2021 goes further potentially violating the informational separation of powers as it allows the replication of the ICN database in the database of the federal government or state government, disconsidering filters such as purpose limitation and foreseeing a single-block informational structure for the whole government.

The risk to the data subject fundamental rights and liberties presented with the lack of separational information of powers is of an abusive secondary use, not in accordance with the purpose of the data collection.

3.2 Centralization of databases

The ICN’s database is composed of six other different databases that were joined together by 2017 law. The first concern with centralized databases is related to the security of information. In this matter, the Brazilian government has already had significant security incidents with databases from the Ministry of Health (Instituto de Defesa do Consumidor (IDEC), 2020) and the Ministry of Education (Naísa, Reference Naísa2021). In less than a week, in December 2021, people identifying as the same hacker group have invaded servers from the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Economy, the National Agency of Transportation, and pages from the Digital Government (Murakawa, Reference Murakawa2021). Another concern is what such a concentration of information represents in terms of power to the government body responsible for the database and how it affects the privacy and data protection rights of citizens.

Lister (Reference Lister1970) highlights that large-scale personal data systems cause fundamental changes in society, increasing the opportunities for citizens to be surveilled by the government and the sheer intensity of this surveillance: “as an immediate matter, they lengthen and deepen institutional memories, thus reducing still further the likelihood that even isolated misconduct will be forgiven or forgotten.” What happens is that technical possibilities brought by a centralized system with a large database facilitate state surveillance, tensioning two different discourses, one of efficiency, of having the data and what can be done with it in terms of security and public policies and one of data protection. Lyon (Reference Lyon2009, p. 4) highlights that identification is the first step for surveillance, but that the contemporary digital identity systems provide a reach and effectiveness never seen before.

In Brazil, we are currently facing a rise in techno-authoritarianism,Footnote 9 through practices such as centralized personal databases being created and abusively used for intelligence activities, and that is directly related to the ICN. One of the great risks of the ICN database, as already reported, is the secondary use of its data for purposes other than identification, as the case reported on ADPF 695, in which the Intelligence Service tried to access citizen’s data taken for their drivers’ license for intelligence purposes. The ICN law, as it stands, already allows the sharing of its biometric database with the police forces in Brazil (article 3, Section 2).

Moreover, the centralization of databases could go against the LGPD’s obligations of data controllers to maintain the security of data (articles 46 and 47) as well as the orientation of the Law that the data should be kept in an interoperable format and shared for the execution of public policies (article 25) (Lei nº 13.709, 2018). The same orientation as to the interoperability of data is present in the Digital Government Law (14,129, 2021).Footnote 10

The two risks portrayed to the data subjects’ fundamental rights and liberties here are the insecurity of data and the privacy risk (surveillance).

3.3 Biometric data, big volume of data: a high risk and the role of DPIAs

The ICN Law establishes in its article 2 that the ICN database will be constituted mainly by the biometric database from the Superior Electoral Court, among other databases. Initially, the Electoral Justice’s idea of building a biometric database was to serve the purpose of making the Brazilian electoral process even more secure, avoiding, thus, a wrongful authentication of a person. However, once the ICN Law was approved and foresaw an information architecture around the Electoral Justice’s database, there was a significant shift in the purpose in which the citizen’s biometric data would be used, in relation to the purpose why it was collected.

Alongside, the draft bill 3,228, 2021, proposed by the federal government, foresees the creation of an authentication service to private parties through biometric data using the ICN database. Such a service would be performed either by the Superior Electoral Court or by another public or private body, depending on the legal agreement defined by the parties. The LGPD allows for the National Data Protection Authority to regulate the communication and sharing of biometric data between controllers of data for economic purposes, due to its sensitivity.

Since biometric data are considered sensitive data by the Brazilian General Data Protection Law,Footnote 11 it is subject to a more restricted hypothesis of data sharing and processing. There is also a specific provision in article 11, paragraph 2 of the LGPD which states that whenever there is processing of sensitive data for the execution of public policies without the consent of the data subject, such waiver of consent should be publicized (Lei nº 13.709, 2018), which has not occurred with the ICN’s biometrics.Footnote 12 Differently from other kinds of sensitive data such as political opinions or philosophical beliefs, biometric data are related to the physical body “raised to the level of the electronic body in face of technological potentialities” (Rigolon Korkmaz, Reference Rigolon Korkmaz2019, p. 44, freely translated), thus relating to some of the most intimate and permanent aspects of the individual.

The situations indicating high risk related to data processing, which would trigger the obligation to elaborate a DPIA, have not been established by the LGPD nor, yet, by the Brazilian Data Protection Authority, which is still regulating the matter. However, the Authority has issued some guidelines on other matters that have touched upon the subject. On the Resolution 2/2022, regarding the application of the LGPD to small and medium enterprises, article 4 of the Resolution established that it is considered a high risk data treatment if there is present one general criteria and one specific criteria determined in the article (Autoridade Nacional de Proteção de Dados Pessoais, 2022). The general criteria are treatment of data on a large scale or treatment of data that can meaningfully affect interests and fundamental rights of the data subjects. The specific criteria are use of new and innovating technologies, surveillance or control of public accessible areas, decisions taken only based on automated treatment of personal data, including those meant to create a personal profile, professional, of health, of consumer and credit or aspects of the personality of the data subject, use of sensitive personal data, or personal data of children, adolescent, and the elderly. The guide elaborated by the Authority and the Superior Electoral Court for the Elections (Autoridade Nacional de Proteção de Dados Pessoais & Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, 2021), paragraph 76, says it is highly recommended to elaborate a DPIA in data treatment situations where there is a high risk, and the example of such a situation is the treatment of sensitive data on a large scale.

In addition to the provisions in the Brazilian normative framework, in the European context, the use of biometric data reveals a risk trigger, according to the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party (2017) “Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) and determining whether processing is ‘likely to result in a high risk’ for the purposes of Regulation 2016/679”.

The potential for biometric data processing to result in high risk to the rights and freedoms of data subjects is directly related to the characteristics of sensitive personal data. It means that they are more susceptible to be used for discriminatory purposes, as stated by Konder (Reference Konder, Tepedino, Frazão and Oliva2019), which justifies the differentiation in sensitive data processing regime—to add an extra layer of protection for data subjects.

There is also a concern on the quality of the biometric data in the ICN database—being the quality of data one of the pillar principles of the LGPD, foreseen in its article 6, V (Lei nº 13.709, 2018). That consideration is especially relevant considering that the ICN is the result of a number of different databases, who could have different quality of data. Only recently, in August 2021, the Superior Electoral Court created a commission to deal with inconsistencies in the biometric data it holds. According to the Court, 54,000 cases of inconsistencies have been discovered since 2014 (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, 2021c).

These concerns reveal the urge to develop public policies—in this case, the digital identity’s public policy—that take into account the data protection rules and principles from the very beginning. In this sense, Beduschi (Reference Beduschi2021), when writing about digital identities for post-Covid-19 societies, highlights the importance that digital identity systems incorporate data privacy by design and by default, avoiding the supposed trade-off between privacy and security. The author highlights that data privacy by design and by default implies not only the implementation of technical measures relating to the design and operation of hardware and software to comply with data protection principles but also a change in organizational strategies and practices. As part of that incorporation, she concludes that the development of digital identity systems should be preceded by the conduction of DPIAs. The fact that Beduschi gets to this conclusion under the GDPR’s logic does not exclude its translation to the Brazilian data protection reality, as the LGPD is highly influenced by the European regulation.

Considering the sensitivity and uniqueness that are inherent to biometric data, Gelb and Clark (Reference Gelb and Clark2013) surveyed 160 cases in which biometric identification has been used for economic, political, and social purposes in developing countries. What the authors recognize is the need for more empirical evaluation and more open performance data on the inclusion and accuracy of the identification systems themselves, since there have been successful cases from a developmental perspective as well as failed cases, being the relevant factor to distinct them the context of the country and the actual application of technology. Regarding privacy, the authors highlight that there are linkages of databases using biometric technology that threaten privacy in such applications and data protection frameworks should cover these issues, with access to such linkages being exceptional and security related.

In this sense, the use of an immense volume of biometric data, as is the case of the ICN, could result in a high-risk trigger, revealing the potential for harming the data subjects’ fundamental rights and freedoms, since the current ICN structure may collide with some core data protection principles, such as the principle of purpose and data quality. This high-risk trigger, thus, should lead to the conduction of DPIAs, in order to comprehend the vulnerabilities of the ICN system and establish measures to minimize its risks—what, however, has not been done in Brazil.

3.4 Lack of publicity of data processing and how to exercise the data subjects’ rights

Besides the ICN Law’s potential violations of the LGPD, there are also omissions of the Law that can possibly compromise the data protection subjects’ rights. In this sense, the ICN Law does not foresee the facilitated access of the data subject to information concerning the processing of their data, as the LGPD determines in article 9, for compliance with its principle of free access.

There is also no provision that preserves the rights to confirmation of the existence of the processing, access to the data, correction of incomplete, inaccurate or out-of-date data, and information about public and private entities with which the controller has shared data (article 18 I, II, III, and VII).

Considering that the ICN is a public policy, its data processing should follow the specific rules established by the LGDP for the public sector. According to the Brazilian General Data Protection Regulation’s article 23, the data processing conducted by the public sector must attend its public purpose and has to achieve public interest, whereby it is necessary to inform, clearly, the data subject on the hypothesis of data processing, its purpose, and the procedures and techniques used in the public policy (article 23, I).

The aforementioned obligations are related to the constitutional public administration principle of publicity. As stated by Filho (Reference Filho2020), the principle of publicity indicates that the public administration’s acts should be as public as possible to citizens, in order to provide tools for the social control of the public administration’s activities, because it is only with transparency that citizens will be able to assess the legality of its actions.

Taking into account the aforementioned obligations, and the precautionary principle—which has been recognized as one of the guiding principles of administrative activities (Filho, Reference Filho2020)—the deployment of a digital identity system such as the ICN should be preceded by a DPIA, as stated previously in Section 3.3, since it would be an opportunity to identify the risks for the data subject from the data processing and include tools to minimize and deal with those risks (Harris, Reference Harris2020).

However, the mere conduction of a DPIA is not enough to fully meet the principle of public interest: its publication would be necessary to move toward an active transparency of the public sector, in a way that the public administration would allow for the social control of its public policies—in this case, the ICN—to understand whether there are or there are not potential violations of data protection rules and principles.

4. The Brazilian Government’s Digital Transformation

The Brazilian digital transformation aims at digitizing all the public services that are offered by the federal government and centralizing them in one platform, the “gov.br”. To access these services, though, the user will be authenticated by the data that composes the ICN database. It means that the implementation of the digital identity system in Brazil is umbilically related to the digital transformation process that has been locally undertaken. The close relationship between the government’s digital transformation and the national digital identity system reveals the need to briefly comprehend the digitization process of the Brazilian government.

In the Covid-19 pandemic scenario, the demand for digital government services in Brazil rose, the reason why the national federal government followed the same path of other countries: heavily investing in the digitization of its services. According to information released in November 2021 by Agência Brasil (2021), more than 1.5 thousand of its public services have been digitized since 2019. This rate led Brazil to be recognized by the World Bank Group as the 7th country listed in the GovTech Maturity Index (Governo do Brasil, 2021b).

The movement toward a digital transformation, in which the Brazilian case is situated, is related to Internet access, considering that the TCP/IP protocol is the primary means to make digitized public services accessible to its citizens. However, in Brazil, Internet access is still not universalized, since almost 20% of its population does not have access to the Internet, according to the 2020 edition of the ICT Household survey, conducted by the Brazilian Network Information Center (NIC.br) (2021). It is true that Internet access in 2020 increased, considering the pandemic context, “however, this increase occurred in a context of ongoing historical digital inequalities already known in the country” (Brazilian Network Information Center, 2021, p. 217, freely translated), since the lack of Internet access is higher among the poorest and least educated people.

5. Challenges for the Future: The Use of the ICN as Access to Public Services

Currently, the main use of the National Identity System by the government is the use of its database to provide digital identity for citizens in order to access government services through a digital platform called gov.br. For that end, a legal agreement was signed in 2021 between the Superior Electoral Court, the General Secretary of the Presidency, and the Ministry of Economy (Governo do Brasil 2021a). Even before the agreement was signed, however, there were pilot initiatives using the database for citizens’ identification. Currently, more than 70% of government services are digitized (Oliveira, Reference Oliveira2021) and there are more than 117 million Brazilians with biometric data in the National Identity Database—79.50% of the total national electors (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, 2021d). The federal government has also promoted and participated in workshops with private parties from the financial, aerial, tourism, transportation, health, and education sectors to identify how the Digital National Identity could be used in transactions with the private sector in the future (Escola Nacional De Administração Pública (Enap), 2021). Considering this is the current use of the ICN, this section will provide an analysis of challenges posed to the future in face of the structure of the National Identity System.

Any analysis of potential or real vulnerability in Brazil has to consider the structural inequalities rooted in the country and has to consider that poverty is gendered and racialized. Before the pandemic, 33% of black women were below the poverty line, and in 2021, the rate is 38%—similar to black men. Meanwhile, for white women and men, such a rate was 15% before the pandemic and is 19% in 2021. As for the national population living in extreme poverty, black women represented 9.2% of it before the pandemic, and in 2021 they represent 12.3%, while white men were 3.4% of it before the pandemic and represent 5.5% of it in 2021 (Roubicek, Reference Roubicek2021).

The first concern brought by the use of a digital identity to access services, whether they are public or private, but with greater concern related to public essential services, is regarding exclusion. There are different reasons why one would be excluded, one of them being the lack of a functioning digital identity. For the Brazilian case, the digital identity originates from the civil registries and voter’s database, making it necessary for the person to have a birth certificate to have a digital identity. In the country, there is currently a low rate of unregistered newborns (estimated at 2.6% of the total births in 2017) (Valor, 2019). However, the rate is unequally distributed geographically—it is higher in the poorer regions of the country (9.4% in the North and 3.5% in the Northeast)—making the poorer more likely not to be registered, as well as the older, since the unregistering rate was estimated at 29.3% in 1990, demonstrating that the progress is recent (Valor, 2019).

In Brazil, another factor that could lead to not having a functioning digital identity is not having quality access to the Internet. Research conducted by Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor—IDEC and Instituto Locomotiva in August 2021 portrayed the Internet access of families among the lowest social classes.Footnote 13 Most people interviewed accessed the Internet from a smartphone (91%) and through the smartphone network—3G/4G (90%). On average, individuals had access to the Internet through the smartphone network only during 23 days in the last month. For the rest of the time, their Internet was blocked for lack of payment for further use. Additionally, from the people interviewed, 39% stated they had not accessed public policies due to the lack of Internet access on their smartphone, 33% had not accessed public services, and 28% had not accessed social assistance benefits, such as the emergency relief cash transfer due to the Covid-19 pandemic. All of these numbers are higher among users that have smartphone plans with Internet use restricted to some apps (Instituto de Defesa do Consumidor (IDEC) & Instituto Locomotiva, 2021).

In the literature, one example of exclusion from services for the use of digital identities comes from Masiero and Arvidsson (Reference Masiero and Arvidsson2021), who show how the incorporation of Aadhaar in the PDS, a food security scheme, excluded genuine beneficiaries that could not be authenticated by biometric due to failure in the technology. Another example from Aadhaar is the starvation death case of 11-year-old Santoshi, whose family was excluded from the list of beneficiaries of cheaper priced food grains obtained via ration cards because they did not have an Aadhaar number (Global Network for the Right to Food and Nutrition, 2021). Similar situations could happen in Brazil, if we were to link essential social aid services to a digital identity, considering that we still have people without birth registration and with restricted access to the Internet, as portrayed above. Regarding the birth certificate, it is already a restricting factor to access the cash transfer program, “Bolsa-Família,” Escóssia (Reference Escóssia2019), accompanied adults who went to the judiciary system to have their birth certificates issued since they were not registered when they were babies, and one recurring reason for seeking the birth certificate was to join the cash transfer program. Putting one more conditionality, a digital identification, would only make a program harder to access.

Beyond the concern of exclusion from not having a functioning digital identity, whether for lack of documentation or lack of internet access, another source of concern is related to privacy and surveillance. As Martin and Taylor (Reference Martin and Taylor2021) describe, digital identification systems are a “double-edged sword,” as they allow for the government to classify and sort its most vulnerable population, at an inevitable risk of function creep from identification to surveillance and controlling. Thus, the same visibility that is advocated for developmental purposes—for inclusion in public policies—opens space to “possible manipulation by those interested in policing and optimizing their behavior” (Martin and Taylor, Reference Martin and Taylor2021, pp. 50–51).

Weitzberg et al. (Reference Weitzberg, Cheesman, Martin and Schoemaker2021) note there is a dialectical relationship between surveillance and recognition and ambivalences of power inherent in digital identity interventions in aid, and that it is necessary to engage critically to evaluate what components of data collection and identification are essential in delivering aid and the potential benefits to using digital technology for aid distribution. They point that this evaluation must observe the specific social and technical conditions at place and assess which privacy by design approaches can be deployed and which privacy enhancing technologies can be used in order to mitigate surveillance. In this sense, it is worth bounding that technology is not neutral in terms of power relations in society—the greater harms are for the ones that depend most on it. For example, Krishna (Reference Krishna2021) demonstrates how informal workers had to give their Aadhaar numbers to be able to access platforms for domestic work and car services, even if the clients were not obliged to use their Aadhaar number to hire such services.

In Brazil, one example of such surveillance and controlling (Martin and Taylor, Reference Martin and Taylor2021; Weitzberg et al., Reference Weitzberg, Cheesman, Martin and Schoemaker2021) of vulnerable populations when providing needed resources is in the cash transfer program Bolsa Família. Valente and Fragoso (Reference Valente and Fragoso2021) explored a data justice perspective analyzing the Brazilian Bolsa Família Program, the world’s largest cash transfer program, which covered 43 million people (14 million families) in June 2020, being most of its beneficiaries black women. The authors note how the database that holds the beneficiaries’ data is accessible to private companies who provide public services, and how the database has been compromised in the past, when beneficiaries have received messages as part of a scam promising new benefits and had their phones infected with malware, or received messages from electoral campaigns. Valente and Fragoso also highlight that for the sake of transparency, the beneficiary’s name, social ID number, and the amounts received as social benefit are published online, in a heightened surveillance effort. They conclude that such facts represent injustices in the way beneficiaries are made visible and represented due to their data, and serve as an alert to the use of data in social policies in Brazil.

Finally, a specifically vulnerable group of the population that could potentially be harmed by the use of digital identification for the access to public services is the transgender community. Brazil is the country with the highest number of deadly violence against transgender people (Lopez, Reference Lopez2020; Sudré, Reference Sudré2020) and the use of digital identification to access services can lead to experiences of discrimination, considering that the digital identification is based solely on the birth certificate or voter’s registration, which do not necessarily have space for the social name—the name that the person wishes to be called and recognized by, and which is allowed by law and regulations to be used in federal public services, education and health services, even by minors, who have more difficulty legally changing their name. Research conducted by Caribou Digital (2020) showed the conflict between gender identities in the making among children and youth in Brazil and the static identification given at birth.

6. Concluding Remarks

The Brazilian National Civil Identity System is already a reality, as can be seen from the recent efforts made to implement it, and it is linked to the digital transformation process that Brazil has been conducting in the last few years. The main finding of the research is that the information structure of the ICN unfolds potential conflicts with the Brazilian data protection legislation, notedly because of the arrangements of data transferring between public administration bodies, the centralization of databases, the large use of sensitive data, and the lack of publicity of data processing and exercise of data rights.

Currently, the primary use of the ICN is related to the user’s authentication in the “gov.br” platform, the Brazilian federal government initiative to centralize all digital public services available. As this use of a digital identity system relates to social development, it also raises concerns related to exclusion, privacy, and surveillance, especially directed to social groups that are structurally and historically marginalized in a structurally unequal society as Brazil. The implementation of gov.br should be a theme for future academic work.

The tensions between the structure of the ICN and the local data protection legislation point to the relevance of addressing data protection issues in the digital identity policy that has been developed in Brazil, and how the recent data protection legislation has not necessarily been embraced by the government. Not only but also the set of concerns that arise from the current use of the ICN to access public services reveals the need to look upon the Brazilian National Identity System beyond data protection, through a data justice (Taylor, Reference Taylor2017) perspective, since this approach will take into account other complexities and characteristics which, if not properly considered and addressed, can result in high impacts or risks to the rights of the citizens, as the exclusion from government services and public policies.

Acknowledgment

This paper results from an abstract presented at the Trustworthy Digital ID Conference, organized by the Alan Turing Institute.

Funding Statement

The research presented in this paper is part of a larger research project conducted by Data Privacy Brasil Research Association supported by Open Society Foundations. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Data curation: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Formal analysis: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Investigation: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Methodology: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Supervision: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Validation: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Writing—original draft: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.; Writing—review and editing: B.B., M.G., M.M., N.P.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.