1. Introduction and positionality

I am a Nigerian and a US American. As a human animal who is a part of nature, I inhabit multiple spaces of privilege and lack of privilege. I am a cisgender, heterosexual, Christian male. Simultaneously, I am a Black Nigerian in the US from an immigrant family. I am a member of the indigenous Ibibio people group and my name, Anietie, is a shortened version of the phrase ‘Who Is like God?’ When I write from an indigenous perspective, I tend to write from a perspective of African indigeneity which is different from indigenous perspectives in the Americas or Australia. There are many other parts of my background and identity that place me in positions of privilege or disadvantage depending on the context – country of residence, education, income, and so forth. Many of those have changed throughout my life.

One influential position or privilege I hold is the position of designer. I have practiced design in various communities around the world. I define communities as the group of beings for whom design is being done. In this paper, the term ‘we’ refers to those various groups or communities and myself, who, together, have practiced radical participatory design (RPD).

The purpose of this paper is four-fold. First, I am demythologising, decolonising, and refuturing participatory design (PD). Others have also critiqued PD. I am going further to decolonise it and show one picture of what PD can look like on the other side of decolonisation. There are other ways people are decolonising PD and I compare those in this paper. Second, in order to critique, I want to facilitate conversation and comparisons between PDs with different onto-epistemic centres. I want to place what we practice when we say PD in conversation with what others mean by those words. In order to do that, I must define what we practice. I have added the word ‘radical’ to differentiate what we practice, and this paper expounds on that practice. Third, in order to compare, I want to share a systematic study of RPD. The problem with conversing with other PD practitioners or projects is that it is difficult to understand what participation means in various projects, to what extent people were included, the ethics of the participation, or an evaluation of the participatory process. Even though systematisation can be a tool of colonialism, I use it to open up pathways of comparison and facilitate the ability of readers to implement RPD. Lastly, I want to encourage more designers in organisations to practice RPD. Despite any prior critique of PD, the field of design is largely unaffected. It is very easy for an academic to do something similar to RPD and much more difficult for designers in the private, public, and nonprofit sectors to do the same. I hope to increase the practice in those sectors, especially.

Due to those goals, in Part I of this paper, I review the pervasive problems with PD, decolonise the history of PD and participatory research (PR), and share a typology of participation that can be helpful to view different kinds of design. Using that typology, I describe RPD, its components and models, based on induction from lived experiential and relational knowledge. In Part II of this paper, I discuss the benefits, difficulties, tips, ethics, evaluation, and organisational barriers of RPD as well as a few ways to overcome those barriers, again induced from experiential and relational knowledge (Udoewa Reference Udoewa2022a ).

2. Literature review of problems

Participatory design processes are not new. Communities ‘unofficially’ have used PD processes to solve community problems for millennia (Sanoff Reference Sanoff2011). Specifically, in western design practices of design, technology, and innovation companies, PD processes have increasingly become popular in the late twentieth century to today (Sanoff Reference Sanoff2011; Hartson & Pyla Reference Hartson and Pyla2012; Hess & Pipek Reference Hess and Pipek2012). This trend is most demonstrated by the now thirty-two-year history of the Participatory Design Conference, from 1990 to 2022 (Simonsen Reference Simonsen2022). Simultaneously, many issues, concerns, and problems have been raised about how PD is theorised, framed, defined, practiced, and evaluated (Kensing & Blomberg Reference Kensing and Blomberg1998; Robertson & Simonsen Reference Robertson and Simonsen2012; Frediani Reference Frediani2016; Charlotte Smith et al. Reference Charlotte Smith, Winschiers-Theophilus, Paula Kambunga and Krishnamurthy2020).

What is immediately evident, both from a literature review of PD and from conversations with other participatory designers, is that everyone in the PD community means something different when they use the term PD (Vines et al. Reference Vines, Clarke, Wright, McCarthy and Olivier2013, Reference Vines, Clarke, Light and Wright2015; Frauenberger et al. Reference Frauenberger, Good, Fitzpatrick and Iversen2015; Halskov & Hansen Reference Halskov and Hansen2015). The initial excitement of finding someone or some group who is using the same participatory process, gives way to confusion or disappointment because the other person or group actually is using a different process. This confusion stems from no shared definition of what PD is. Researchers and designers use the term PD to signify different understandings of power and empowerment, different levels of politics in the design process, different groups of people, different methods, different goals of participation, and different amounts and configurations of participation (Ertner, Kragelund & Malmborg Reference Ertner, Kragelund and Malmborg2010; Halskov & Hansen Reference Halskov and Hansen2015; Fischer, Östlund & Peine Reference Fischer, Östlund and Peine2021).

There are researchers and designers who use the term PD to signify the participation of internal or external stakeholders (Srinivasan & Shilton Reference Srinivasan and Shilton2006; d’Aquino & Bah Reference d’Aquino and Bah2014). Others use the term to mean the community who will use the product or service (Ssozi-Mugarura, Blake & Rivett Reference Ssozi-Mugarura, Blake and Rivett2017; Cho & Ho Reference Cho and Ho2020). Still others use the term to mean all internal and external stakeholders including community members and internal organisational stakeholders and executives (Byrne & Sahay Reference Byrne and Sahay2007; Vázquez et al. Reference Vázquez, Vargas, Unger, De Paepe, Mogollón-Pérez, Samico, Albuquerque, Eguiguren, Cisneros, Rovere and Bertolotto2015). In this paper, we focus PD on the participation of the people for whom or on whose behalf we are designing – the community. It is their expertise that should drive the process.

Methodologically, we have found that PD can be used to mean interacting with the community during the design process, a method, a way of conducting a method, or a methodology. There are researchers and designers who use PD to mean the interaction with the community during the process: ethnography among the community, prototyping and testing among the community, and launching the product or service to the community. Because this is simply the generic design process, we will not spend time discussing this understanding of participation. Others use the term to mean a specific method, for example, choosing between a usability test, an interview, or participatory research or design (Fang Reference Fang2012; Adeagbo & Naidoo Reference Adeagbo and Naidoo2021). There are researchers and designers who use the term to signify a way of conducting a method. For example, we can run a design studio with our designers, or we can invite community members to take part in the design studio with us. In this way, we are doing the design studio method in a participatory way (Walujan et al. Reference Walujan, Hopkins and Istandar2002; Priya, Shabitha & Radhakrishnan Reference Priya, Shabitha and Radhakrishnan2020; Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Ochiai, Tseng and Deng2022). Still, others use PD to signify a methodology – a collection of methods or a toolkit with guiding principles that guide one to choose specific methods in the toolkit at specific times (Spinuzzi Reference Spinuzzi2005; Hwang Reference Hwang2012; Birachi et al. Reference Birachi, Hoekstra, Jogo and Mekonnen2014). Lastly, there are many times we do not know what PD means methodologically because it is not explicitly defined in a particular research paper, article, talk, or blog post.

Each of the aforementioned methods and meanings of PD has different implications on the politics of design, the definition of participation, and the goals of the participatory process (Halskov & Hansen Reference Halskov and Hansen2015; Bossen, Dindler & Iversen Reference Bossen, Dindler and Iversen2016). Mutual learning is one goal or one definition of participation stated by certain participatory designers (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Aurora, Karanth and Ramaswamy2002; Winschiers-Theophilus et al. Reference Winschiers-Theophilus, Chivuno-Kuria, Kapuire, Bidwell and Blake2010; Ai Reference Ai2019). Another common goal or definition of participation is eliciting the community’s perspective (Moraveji et al. Reference Moraveji, Li, Ding, O’Kelley and Woolf2007; Neves Reference Neves2014; Rajamany et al. Reference Rajamany, van Biljon and van Staden2022). Other goals are greater ownership or facilitating better outcomes and change (Chirowodza et al. Reference Chirowodza, van Rooyen, Joseph, Sikotoyi, Richter and Coates2009; Yasuoka & Sakurai Reference Yasuoka and Sakurai2012; Alves Villarinho Lima & Almeida Reference Alves Villarinho Lima and Almeida2021). Kim focuses on participation as interacting with a service after launch (Kim Reference Kim2020). Again, there are research papers, articles, blogs, and talks that do not explicitly describe the goal or definition of participation at all (Clement et al. Reference Clement, Costantino, Kurtz and Tissenbaum2008; Johannessen & Ellingsen Reference Johannessen and Ellingsen2008).

Though there are multiple attempts to measure the effects of participation, without a goal or a definition of participation, it is difficult to evaluate whether empowerment happened or the process was successful, which can be different than the evaluation of the design product or artefact (Ibrahim & Alkire Reference Ibrahim and Alkire2007; Luttrell et al. Reference Luttrell, Quiroz, Scrutton and Bird2009; Jupp, Ali & Barahona Reference Jupp, Ali and Barahona2010). The PD result or the success of the participatory process is more important than the design because of the effect and impact of the process on the design (Bratteteig & Wagner Reference Bratteteig and Wagner2016). Today, there is still no organic consensus on how to evaluate participatory processes. In fact, formal evaluations are uncommon, often lack details, and are not done in the same participatory way as the, hopefully, participatory project that is being evaluated (Bossen et al. Reference Bossen, Dindler and Iversen2016).

In addition to the aforementioned problems, there have been other critiques of PD – the loss of a democratic commitment, the lack of a posthuman democracy, the oversimplification and ignorance of power dynamics in the community, the lack of understanding of how participation works or does not work in other cultures, availabilities of community members, power imbalance, romanticising local knowledge, reinforcing local power imbalances, etc. (Cooke & Kothari Reference Cooke and Kothari2001; Neef Reference Neef2003; Winschiers Reference Winschiers2006; Kesby Reference Kesby2007; Blomberg & Karasti Reference Blomberg and Karasti2012; Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Duarte, Weibert, Aal, Talhouk and Metatla2019). It would be epistemologically biased and supremacist to cite published critiques, preferring the written word, when communities have known and experienced these problems before they were ever written. So I am sharing a critique based on the experience of communities and projects of which I have been a part. Unfortunately, each of the aforementioned categories of PD – whether interaction, method, way of doing a method, or methodology – has a paradoxical way of maintaining or strengthening the power imbalance (Udoewa Generations n.d.). If designers invite community members to participate, they are reinforcing the power differential, the fact that they have the power to invite or not to invite. They have the power to choose who, when, where, how, and if to invite. All the choices are in their hands. The very act of ‘empowering’ users or community members, reinforces the designer’s own power to do so and the seeming lack of power community members have to participate in their own way on their own terms (Rowlands Reference Rowlands1995; Gaventa & Cornwall Reference Gaventa and Cornwall2008; Toomey Reference Toomey2011; Zamenopoulos et al. Reference Zamenopoulos, Lam, Alexiou, Kelemen, De Sousa, Moffat and Phillips2019; Thinyane et al. Reference Thinyane, Bhat, Goldkind and Cannanure2020).

The power-maintaining act of ‘empowerment’ is a form of colonisation (Udoewa Generations n.d.). Designers and design, technology, and innovation organisations regularly colonise the futures of community members through the ownership, control, and maintenance of power structures governing the products and services community members use to accomplish various goals in their lives. Colonisation, through the guise of PD, exacerbates and compounds the problem because it creates the false expectation that this process and its outcomes will be beneficially different from past colonial experiences.

Research justice and design justice offer us full images of a postcolonial PD practice and how it might function. Research justice, which includes participatory action research, is the eradication of research oppression when community members have access to all forms of knowledge to affect change, recognising their own expertise and knowledge equal to formal modes of knowledge (Williams & Brydon-Miller Reference Williams and Brydon-Miller2004; Assil, Kim & Waheed Reference Assil, Kim and Waheed2015). Research justice equalises the power of cultural and spiritual knowledge of communities, experiential knowledge of communities, and institutional knowledge of research organisations. Design justice insists on ‘community participation, leadership, and accountability throughout a collaborative, transparent design process,’ centred on the community who owns the design artefacts and the benefits, stewardship, and narratives about the artefacts (Costanza-Chock Reference Costanza-Chock2018, Reference Costanza-Chock2020). When reviewing the body of PD, it is difficult to find examples that fit these definitions of research justice and design justice.

Therefore, we introduce the term RPD to differentiate and represent a type of PD that is participatory to the root or core: full inclusion as equal and full members of the research and design team. Unlike other uses of the term PD, RPD is not merely interaction, a method, a way of doing a method, nor a methodology. It is a meta-methodology, or a way of doing a methodology. There are design methodologies that also involve paradigms, mindsets, or orientations; however, they embody both an approach and a set of methods or methodologies (Lincoln & Guba Reference Lincoln and Guba2000; Bradbury Reference Bradbury and Bradbury2015; Nirwan & Dhewanto Reference Nirwan and Dhewanto2015; Yan et al. Reference Yan, Orkis, Khan Sohail, Wilson, Davis and Storey2020). RPD is only a meta-methodology. As an overlay on top of a methodology, practitioners can use any guide, toolkit, and methodology and do it in a critically and radically participatory way.

In this paper, I avoid calling what others call PD, which maintains and strengthens power imbalances between community members and designers, simply ‘PD,’ while adding adjectives like ‘radical,’ ‘relational,’ ‘critical,’ or ‘postcolonial’ in front of what I and others call PD. Instead, I want to practice the decolonising move of decentering the dominant perspective and practice. In order to de-centre all types of PD, I will use an adjective with all kinds of PD. I will call PD, which maintains and strengthens power imbalances between designers and community members, colonial participatory design (CPD). I will use the terms RPD, critical PD, relational PD, and postcolonial PD interchangeably.

Let us define a few terms. Radical comes from the Latin ‘radix’ meaning root. RPD means a design that is participatory to the root, all the way through, from the beginning to the end, from top to bottom. Colonialism is the ideologies, philosophies, policies, systems, or practices that ‘seek to impose the will of one people on another and to use the resources of the imposed people for the benefit of the imposer’ (Asante Reference Asante, Dei and Kempf2006). Colonisation is the enactment, process, or action of imposing the will of one people on another, using resources of the latter for the benefit of the imposer. Coloniality is simply the nature or quality of colonialism or a colonial way of being.

Eve Tuck, an Unangax̂ scholar and associate professor of critical race and indigenous studies, and K. Wayne Yang, a professor of critical pedagogy and indigenous organising, wrote a paper, Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor, in which they argue that decolonisation is literally only about the repatriation of Indigenous land (Tuck & Yang Reference Tuck and Yang2012). Unfortunately, they only associate the word decolonisation with settler colonialism, Americocentrically reducing colonial relationships into a settler-native-slave triad (Garba & Sorentino Reference Garba and Sorentino2020), forgetting that slaves are also indigenous people forcibly removed from their land, and forgetting the relationality of certain pre-modern, European indigenous groups that modern European colonists forsook. Instead, Shoemaker highlights multiple types of colonialism – settler, planter, extractive, trade, transport, imperial power, not-in-my-backyard, legal, rogue, missionary, romantic, postcolonial, etc. (Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2015). Each type of colonialism has associated colonising acts and enactments or colonisation. Thus, land is not the only thing that can be colonised. Knowledge production systems, natural resources, ways of being, currencies, histories, languages, futures, methodologies, bodies, even our minds can be colonised, any resource or asset (Asante Reference Asante, Dei and Kempf2006; Smith Reference Smith2021). When I have asked African or Asian Indigenous persons if their people were colonised even after keeping or regaining their land, they say yes. Different from the indigenous experience in North America and Australia where colonisers never left, the indigenous experience in Africa and Asia includes acknowledged colonisation, not just colonialism, after the colonisers generally left. For example, Zimbabwe and Siamese people were colonised by their postcolonial and uncolonised (settler colonialism) states, respectively (Murdoch Reference Murdoch1967; Dagarembga Reference Dagarembga, Akomolafe, Asante and Nwoye2017). The avoidance of the term colonisation allows people to critique the nature of coloniality or system of colonialism while avoiding any personal responsibility or agency in actual, colonising acts.

Thus, decolonisation is the act or process of freeing one people from the imposition of another, giving the former people control over the resource that was taken for the benefit of the latter. Decoloniality is the nature or quality of a decolonising project, movement, practice, system, autonomous region, philosophy, or ideology, or a decolonial way of being. Certain researchers attempt to decolonise PR through methods instead of a meta-methodology (Seppälä, Sarantou & Miettinen Reference Seppälä, Sarantou and Miettinen2021). For example, Charlotte Smith et al. (Reference Charlotte Smith, Winschiers-Theophilus, Paula Kambunga and Krishnamurthy2020) and Evans, Leah & Petrović (Reference Evans, Leah and Petrović2020) attempt to decolonise PD. In both cases, as Charlotte Smith admits, the researchers chose the methodologies and level of participation, and there was no remuneration for community members. Stanton (Reference Stanton2014) and Olko (Reference Olko2019) attempt to decolonise community-based PR, also providing no remuneration for community participants. Both show work that does not extend to design, and Stanton uses a designer-dominated understanding of project timelines. Olko does work to create an indigenous research methodology and focuses on empowerment instead of divesting of power, treating community knowledge and researcher knowledge as equal, different from an RPD understanding. The most similar work to RPD may be work like Cahill and the Fed-up Honeys (Cahill Reference Cahill2005, Reference Cahill2006). Their work differs in that it is not clear what transformation occurs from the work or if the participant remuneration was equitable to the professional researcher remuneration. There have been times when Cahill co-authors with the community and others where she has authored solo, different from RPD. Because the participatory process of most papers is not fully explicated in terms of choice of methodology, evaluation, transformation, remuneration, equity, initiation, negotiation, it is difficult to understand how similar it is to RPD.

The last term to define is postcolonial which normally refers to the period after formal colonial rule, while postcolonialism or postcolonial theory studies the political, cultural, and economic legacy of imperialism and colonialism. Postcolonial theory has been criticised as a Eurocentric critique of Eurocentrism which is why a decolonial approach goes further to de-link the ontology and epistemology of coloniality (Ali Reference Ali2014). When I say another name for RPD is Postcolonial Design, I do not mean design in the postcolonial age. Rather, I mean a type of design that is after the domination of colonial design that disempowers communities and maintains hierarchies. I mean a post-(colonial design).

In the remainder of the paper, I first attempt to decolonise the usual PD and PR history that starts in Scandinavia or South America, showing how its history goes much further back in time. Next, I discuss the typologies of design participation and place RPD in context by comparison. Then I introduce RPD and describe its components, as a way to evaluate and validate the participatory nature of a process, and its immediate implications. Throughout the paper, I will refer to a few case studies to elucidate the ideas.

3. Brief alternative history of participatory research and design

Most histories of PD begin with the Scandinavian model of collaborative design in the 1970s. Most histories of PR begin either with the Southern tradition in the 1970s with Paolo Freire (Reference Freire1970) and Fals-Borda (Reference Fals-Borda1987) or the Northern tradition in the 1940s with the theories of Lewin. However, beginning in the 1940s or 1970s represents a colonial history of PD and PR. In order to decolonise the history of PD and PR, we must first define design and research.

3.1. Glimpses from a decolonised history of participatory research

What happens if we define research simply as one or some combination of gathering, creating, storing, organising, analysing, transmitting, or using information (Udoewa Decades n.d.)? Then PR is simply doing those activities in a participatory way, in which the community participates. With such a definition we can see that communities have always practiced PR since the beginning of communities.

First, let us travel back between the 15th and 19th centuries. Oral histories as far north as South Carolina and as far south as Brazil, maintain that African women, who were captured, marched to the coast, stored in castles, and shipped across the Atlantic, braided and hid grains of rice in their hair as a means of defiance, preserving culture, and surviving (Carney Reference Carney2004; Rose Reference Rose2020). This is documentation, preservation, and transmission of information, for the rice eventually fed the plantation owner as well. Lastly, in a type or PR we call participatory appraisal, slaves in the Americas could then examine what food assets everyone had, to see what they could grow to eat and survive.

Second, we can travel to Ancient Greece, where midwives looked for methods of birth control. Animal herders shared that when their animals ate certain herbs their birth rate was lower (Riddle Reference Riddle1997). This transmission and passing of information is research.

Third, we can travel before homo sapiens, where early people used sharpened stones 2.6 million years ago (Pruitt Reference Pruitt2019). After much evolving trials and tests, stone hand axes emerged around 1.6 million years ago. Eventually they developed new knapping tools around 400,000 to 200,000 years ago, cutting blades 80,000 to 40,000 years ago, and small, sharp microblades 11,000 to 17,000 years ago. Then they developed axes, celts, and chisels during the Neolithic period around 12,000 years ago. All of this experimentation with materials and stones is experimental research or Research through Design (Jonas Reference Jonas2007).

Therefore, PR is not new. PR is ancient. The reason scholars create relatively recent PR histories is because of the rise of the professional researcher as a profession. It is important to note that there are design and research scholars who define PR as research in which community members engage with a required professional research. However, research has always been a public and participatory task or activity that was part of most jobs or roles. When we epistemologically open up our understanding of knowledge beyond mainstream, institutional knowledge to include experiential, cultural, embodied, aesthetic, and spiritual knowledge, the definition of research as ‘investigation’ is transformed to a pluriverse of definitions: learning circles, oral history, songs, storing info in a body, shamans, experimentations, receiving info stored in a body, storytelling, propagating information in a socio-human system, apprenticeships, and so forth. Likewise, the purpose of research is transformed from ‘to establish fact or reach a conclusion’ to a pluriverse of purposes: to survive, teach history, share values, do justice, answer a question, resist, leave a legacy, transform society, pass down culture, steward a system, etc.

3.2. Design thinking versus human-centred design

Design thinking (DT) and human-centred design (HCD) are often used interchangeably (Lake Reference Lake2018; Sekhar Reference Sekhar2018). I do not intend to disrupt this equivocation. I do want to clarify what I mean when I use the terms DT and HCD. Design thinking, literally, is thinking and acting and doing like a designer. This involves at least three activities (Drysdale Reference Drysdale2018; Chicago Architecture Center 2019; Udoewa Decades n.d.).

-

(i) Some type of information gathering, intake, or research.

-

(ii) Some type of idea generation.

-

(iii) Some type of prototyping and testing a solution.

If one does those things, she is thinking, acting, and doing like a designer; she is designing. Human-centred design is simply one way of doing design – designing so that one centres each phase of the design process on the humans for whom one is designing. Human-centred design is only one way, not the only way, of designing. One can also implement Activity-centred Design, Task-centred Design, Behaviour-driven Design, Test-driven Design, Biomimicry, Universal Design, Pluriversal Design, Values-sensitive Design, Circular Design, Speculative Design, Transition Design, Critical Design, Transgenerational Design, etc. (Lewis & Rieman Reference Lewis and Rieman1993; Woudhuysen Reference Woudhuysen1993; Benyus Reference Benyus1997; Gay & Hembrooke Reference Gay and Hembrooke2004; Mattu & Shankar Reference Mattu and Shankar2007; Dunne & Raby Reference Dunne and Raby2013; Davis & Nathan Reference Davis and Nathan2015; Irwin Reference Irwin2015; Moreno et al. Reference Moreno, De los Rios, Rowe and Charnley2016; Leitão Reference Leitão2020; Levy Reference Levy2020). One can even implement PD, the focus of this paper.

PD, then, is simply doing those activities (intaking information, ideating, and creating something to try or test) in a participatory way, in which the community participates (Asaro Reference Asaro2019, Vogel Reference Vogel2021, IGI Global 2022, Udoewa Decades n.d.). When defined as such, I hope it is clear that community design is inherently participatory, and communities of humans have always engaged in PD processes for hundreds of thousands of years. I note, again, that certain design scholars disagree and view PD as only occurring when communities work with professional designers. According to my experience and definition, the dynamics of participation by communities who will use a future design, can and do occur without a professional designer. I will share three global examples of communities that organically developed design solutions.

3.3. Glimpses from a decolonised history of participatory design

With ‘more than seventy percent of the population in the developing world’ and ‘more than eighty percent of the population of South Asia’ using medicinal plants for maintaining and improving health, India is an example of a country that has a widely used folk system of medicinal knowledge (Shukla & Gardner Reference Shukla and Gardner2006; Astutik, Pretzsch & Ndzifon Kimengsi Reference Astutik, Pretzsch and Ndzifon Kimengsi2019). To respond to the challenge of the use and conservation of medicinal plants, a natural resource, Indian communities developed three designs. Communities developed traditional systems of medicine (TSMs) that codified medical plant knowledge in texts or ancient scriptures (Ayurvedic, Siddha, etc.). Communities also developed folk medicine in which knowledge is learned by doing and passed down through oral tradition. Lastly, communities developed the expert approach to medicinal plant knowledge management, embodying the knowledge of Spiritual or Shaministic Medicine in people called healers who passed knowledge through apprenticeships. Even though the Ayurvedic and Siddha TSMs were codified more than 3,000 years ago, they represent the codification, and thus institutionalisation, of practices communities had been testing, designing, and using for thousands of years before that, passing the information down through oral tradition just like folk medicine (Shukla & Gardner Reference Shukla and Gardner2006, Astutik et al. Reference Astutik, Pretzsch and Ndzifon Kimengsi2019).

Another pre-1970s example of indigenous community design that also uses oral history is the role of the griot in West Africa, originating in the 13th century. The griot is a community role, created and designed to be a storyteller and oral historian of a community. ‘Entrusted with the memorisation, recitation, and passing on of cultural traditions from one generation to the next,’ griots were the social memory of a people group, a type of embodied design (WACH 2020). They utilised design methods like fables, folktales, songs, epic narratives, poems, instruments, proverbs, and more. The creativity of the griot oral tradition lies in the use of story, a framework deeply embedded in the human psyche, to both remember and convey various histories, but also to make those histories more memorable to the hearers. The application of storytelling to the social science of history is so effective, modern futurists and designers are employing it as a methodology in current design projects (Tuwe Reference Tuwe2016; Bisht Reference Bisht2017).

The third pre-1970s example of community design comes from water resource management–irrigation systems. As early humans began to congregate in larger communities enabled by the transition to farming, communities had to overcome various problems. How does a community grow enough food for a larger group of people? And how do they water all those crops when rainfall is not enough? What do they do if they receive too much rainfall and flooding destroys the crops? To answer the second and third questions, ancient Mesopatamians designed ‘large storage basins to hold water and connected these by canals to their’ fields (Mohammed Reference Mohammed2014). They also built up the banks of the rivers to prevent flooding when the river level was high. These are examples of community design. Though such canal systems were institutionalised around the world, they started as community responses to community problems.

Therefore, PD has been practiced long before participatory action research was introduced theoretically by Lippit and Radke in 1946 and Lewin in 1947, who, themselves, drew from the Scientific Method in Education movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Masters Reference Masters and Hughes1995, p. 1). Participatory design was practiced long before the ‘Father of American Participatory Architecture,’ Karl Lin, started the first community design centre in Philadelphia in 1961 as an example of participatory planning, the same year that Jane Jacobs published her book, ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities,’ as a critique against centralised planning, seeding the participatory planning movement (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1961; Finn & Brody Reference Finn and Brody2014). Even in international aid, PD started long before participation, ‘as a central pillar of the basic needs approach to development, gained prominent support in the 1970s’ (Cornwall Reference Cornwall2002).

There are many more examples of PD in the history of communities even in the pre-1940s 20th century, especially in service learning, community agriculture, civil rights, labour rights, history of women’s rights, children’s rights, etc. (Udoewa Reference Udoewa2022b ). Communities have always addressed problems facing the community using community members. Going further, when we epistemologically widen our understanding of design as a knowledge-creating endeavour beyond mainstream, institutional design, to include design based on experiential, cultural, embodied, aesthetic, and spiritual knowledge, for a variety of purposes that communities pursue, then the model of design-as-problem-solving is transformed to a pluriverse of namologies (studies, perspectives, or ways of designing): problem-solving, legacy-passing, way-finding, justice-creating, purpose-locating, system care, beauty creation, system shaping, self-expression, cultural preservation, future embodiment, etc. (Ibibio Generations n.d.).

Because PD has always been a feature of community life, it does not make sense to talk about the ‘history of PD,’ as if there were a historical moment in time during which PD began apart from the historical start of communities. There is no such moment. This does not mean communities lacked any use for skilled crafts people, artisans, or designers. Rather, our alternative history means these specialists were members of the community and, thus, engaging in PD as opposed to the more recent development of hiring an expert outside and disconnected from the community to lead and resolve a community problem or issue. The reason most histories of PD start in the 1940s or 1970s is because they are documenting CPD, in which design organisations decide to allow or ‘empower’ community members to participate in the process. To differentiate CPD from RPD, we must first define what participation means.

4. The typology of design participation

There are many dimensions that can be used to characterise design participation or to determine whether a design or research process is participatory at all. To simplify the analysis, I will use three dimensions or questions.

-

(i) Who initiates the work, and how much do they initiate?

-

(ii) Who participates, and how fully do they participate?

-

(iii) Who leads the process, regardless of participation, and how much do they lead?

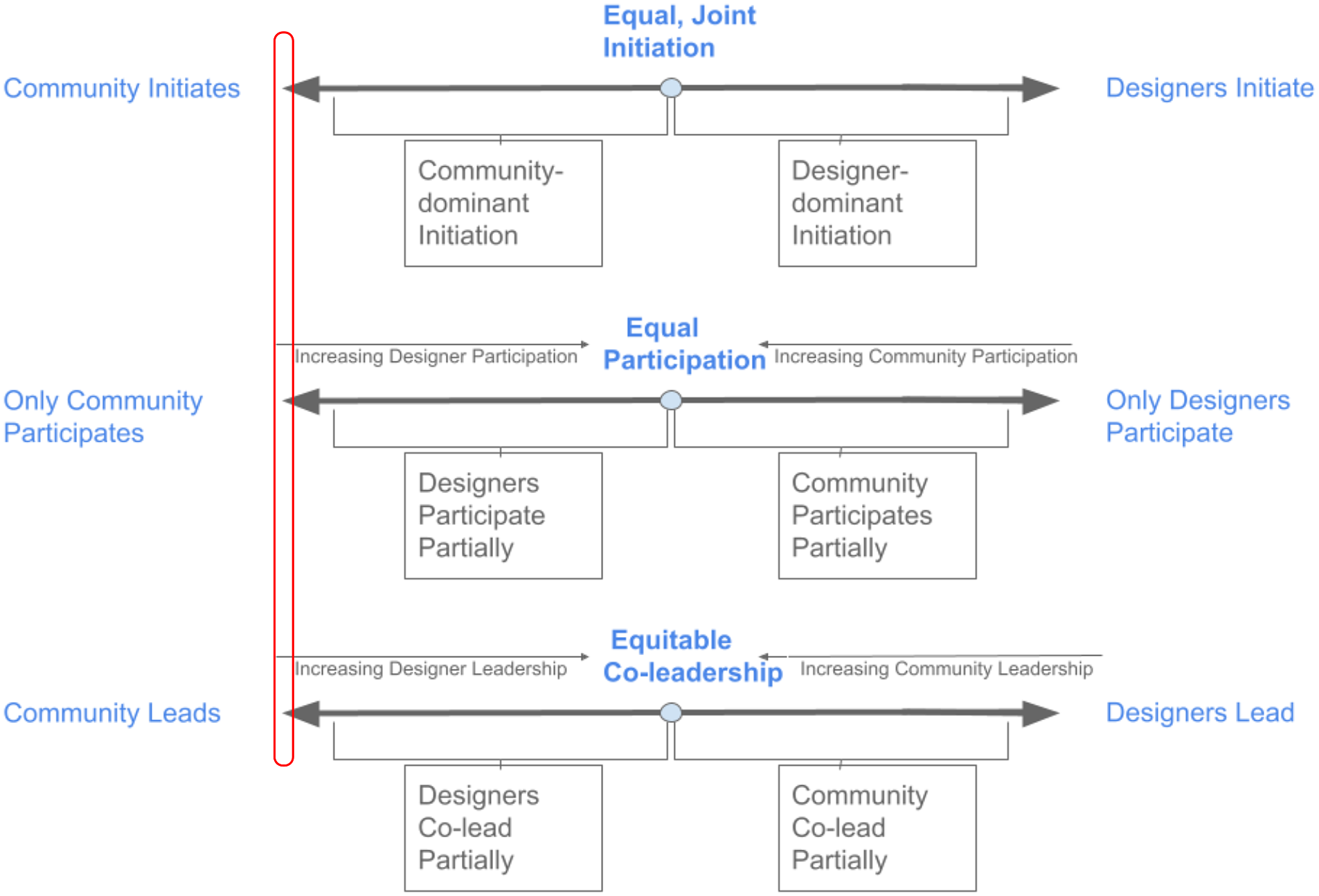

Notice each question contains a second independent clause to understand the extent of the dimension. The second part of each question implies that initiation, participation, and leadership are spectra (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Three axes of participation: initiation, participation, and leadership.

A research or design project can be initiated by the community who will benefit (the left end of the initiation spectrum), designers outside the community (the right end of the spectrum), or some combination of both (between the ends). Sometimes, a community wants to begin work to solve a community problem, and they first contact designers to gauge interest in helping before initiating the project work. Perhaps the designers become excited and help with further recruitment to initiate the project. The designers may have indirectly helped to initiate the project or aided the initiation; however, the community directly initiated the project, which is an example of community-dominant initiation. Likewise, before initiating work, a design group or organisation may contact community members to gauge their interest, availability, and need for conducting PD for a designer-perceived, community problem, which is an example of designer-dominant initiation. One example of equal, joint initiation is at the end of an RPD project, when the designers and community members on the team co-decide to initiate a second, follow-on project because there is more work to do or due to the implications of the current project. Initiation is the only dimension that cannot necessarily disqualify a project as RPD. A community-initiated PD project can be RPD, or CPD if designers usurp power; a designer-initiated PD project can be CPD, or RPD if designers divest of their power. The type of PD depends on the other two dimensions, leadership and participation.

Participation is harder to classify than initiation due to its multiple meanings. Projects can start, run, and conclude with only community members (the left end of the participation spectrum), only designers (the right end of the spectrum), or a combination of both designers and community members (between the ends). Certain designers view interviews or prototype testing with community members as ‘community participation,’ and would classify that as the ‘community participates partially,’ the right half of the participation spectrum (Figure 1). I do not classify it as participation because I am evaluating participation on the design or research team, not participation as a research participant or prototype test participant. Even if one counts interviews as community participation, there are higher levels of participation beyond such implicit participation, levels that move towards the centre of the spectrum – equal participation. For instance, designers may seek community perspectives by inviting community members to participate in design activities, like a design studio or prototype evaluation, making the activity participatory. These invitations represent partial community participation due to the fact that the community is being invited to a session and not always present. Other designers go further and invite community members to an entire phase of activities, such as all activities in the design and test phase. This invitation still represents partial community participation because the community is being invited to only one phase. Other designers increase participation by inviting community members to all activities in all phases – research, synthesis, design, and implementation. From an RPD perspective, such an invitation is still partial community participation because the design team still has meetings, makes decisions, and practices design apart from community members. To explain, these activities relate to the multiple levels of design practice.

The first level of design education and practice are the mindsets for a particular methodology. These mindsets can be used by anyone, even without the title of designer, to bring the benefits of a design methodology to their work. The second and the most common level of teaching is the design process. A workshop or course teaching a design process usually mentions the mindsets and builds upon them with a process. One large difference between an actual design process and a course or workshop teaching a design process is linearity. The design process is inherently nonlinear, yet we teach design processes as if they were linear, which is a helpful structure for beginners. However, there is a third level of design practice and education that shows participants how to take the results of any design method or activity, evaluate it, compare it to the goal of the design process and the current project dynamics, and decide what is the next appropriate step as well as what information should be carried from the completed activity to that next step. This process of interpretation, negotiation, evaluation, goal measuring, synthesis, and decision-making between design activities is what allows designers often to go through a nonlinear process. The use of methods becomes nonlinear, as well, with designers often using a method depicted in a toolkit as only occurring in a particular phase of design, in another phase of design. Designers who say they are using a PD process often conduct this inter-activity process without community members, which means participation is not fully complete nor equal.

To reach the centre of the participation spectrum, equal participation (Figure 1), designers must involve community members even in this sense-making process between design activities. Designers must involve community members in everything, all work and communications for the participation to be truly equal. On the other hand, community members do not have to invite designers to participate in the design process for the process to be participatory because PD is concerned with the participation of the beneficiaries of the design. Community design and community-driven design are inherently participatory (Moss Reference Moss2020). Still, when community members engage in design to solve community problems, they may choose to engage designers for a particular activity (partial designer participation) or for an entire phase of activities like the implementation phase of a project (increased partial designer participation). Also, community members could involve designers in even more participation – all phases in all activities – or ultimately involve designers even in the sense-making, decision-making, and preparation work between activities resulting in truly equal participation.

The last dimension is leadership. It is possible to participate in an activity and have no decision-making power, contribution, or value. Leadership is not a role on a design team, but rather the act of influencing and guiding. A person can be invited into an activity or process, but be prevented from influencing or guiding the process or results. Therefore, community leadership is a necessary component of postcolonial, critical PD. On the left end of the leadership spectrum is community leadership when the community leads the design process. Even if they hire a craftsperson, artisan, or designer as a vendor to implement their choices, they are still fully leading. When the community invites designers to lend leadership and guidance to an activity or phase of activities, participating as a thought partner, then the designers are partially co-leading. When the designers are invited to lend leadership and guidance to all activities of all phases as well as the sense-making and decision-making between activities, the team has achieved equitable co-leadership. Similarly, when community members are invited to lend leadership and guidance to an activity or phase of activities, the community is partially co-leading.

The three spectra of initiation, participation, and leadership can serve as axes in a conceptual three-dimensional space in order to locate and define various types of design approaches (Appendix Figure 1). For example, community design is research and design that only involves community members and is initiated and fully led by community members (Figure 2). Community-driven design fully involves and is fully led by community members. However, it may vary in the amount of partial designer participation and partial designer initiation (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Community design.

Figure 3. Community-driven design.

Colonial participatory design occurs when PD is not fully, critically, or radically participatory to the core, meaning it may or may not fully involve community members in all activities, phases and sense-making and decision-making between activities, and ultimately, community members do not fully lead or co-lead (Figure 4, Appendix Figure 2). We call designer-initiated, designer-led design with only designers, designer-driven design, a type of colonial design (not participatory).

Figure 4. Colonial participatory design (CPD) and design injustice.

Radical participatory design, in contrast, occurs when community members fully lead and fully participate in all activities of all phases including sense-making and decision-making between activities, regardless who initiates, with or without full or partial co-leadership and co-participation of designers (Figure 5, Appendix Figures 3–4). We highlight designer-initiated RPD (Appendix Figure 4) because this is the main challenge design organisations and designers face. Usually, it is much easier for community-initiated projects to be RPD, by nature of the community’s initiation (Guffey Reference Guffey2021, pp. 3–4). The bigger challenge is whether designer-initiated projects can be conducted in a way in which the community fully participates and fully co-leads or leads. Using our understanding of RPD according to the three axes of participation, initiation, and leadership, we can now describe RPD more specifically.

Figure 5. Radical participatory design.

5. Radical participatory design

Radical participatory design is design that is participatory to the root, in every aspect. Regardless of who initiates a project, RPD fully includes the community members in all activities of all phases of the design process and in all interpretation, decision-making, and planning between design activities. In RPD, the community members not only fully participate, but they fully lead and drive the process. RPD is not a method, way of conducting a method, or a methodology; it does not define any design methodology. The community chooses the methodology. It is a meta-methodology, a way of doing a methodology. There are three characteristics of RPD. These characteristics can be used as a way to evaluate or validate the participatory nature of a process, whether it is truly, critically participatory. In Part 2, we will discuss ways of evaluating the success of the RPD process (Udoewa Reference Udoewa2022a).

-

(i) Community members are full, equal members of the research and design team from the beginning of the project to the end. There are no design team meetings, communications, and planning apart from community members. They are always there at every step and between steps because they are full, equal design team members.

Communities are not homogenous. Who decides who the community is? Anytime there is a question about deciding, if the professional designers make it, the leadership spectrum tips toward the designers. At the very least, decisions should be made together by the mixed design team (equitable co-leadership), and at best, the community decides. This is hard to do if the project is initiated by professional designers. In that case, they simply recruit initial community members at the start, and those community members help determine who is needed or whom to recruit. It does not matter if the initial recruitment of community members is not representative. An iterative process led by the initial and growing community members will help determine who should be on the team. Ultimately, the goal is a qualitatively representative sample of the community in a way that honours cultural definitions of leadership and participation, tipping the leadership and participation spectra back towards the community.

Many community members have jobs or other roles and responsibilities and may not have time to participate on the research and design team. Is it possible to pursue equity of participation where community members do not do the work but have decision-making power over the work? To answer this question we must uncover its assumptions and define a few terms. Equality means equal treatment: community members are full design team members. Equity means different treatment to achieve equal outcomes: community members have evaluative or approval power but do not participate due to time. There are two problems with the seeming equity approach.

First, there is no equity or equal outcomes. Community review boards can be implemented well; however, they are only a check and can stop a bad, unsafe, or harmful research plan, idea, or design from moving forward. Unfortunately, CRBs do not determine what research plans, ideas, or designs are created or proposed. If professional designers are framing plans, brainstorming ideas, and creating designs the outcomes will be different than if community members are doing the same thing on the design team. Equity of participation through community approval and accountability is not equity. In other words, communities can provide oversight and the leadership spectrum still be strongly on the side of the designers. Another way to say this is that the participation and leadership spectra are not fully independent. It is possible for the community to participate, be present, and not lead. But it is impossible for the community to fully lead without being present.

Second, the question reinforces white supremacy and centres the professional designer by using a Western designer-dominated notion of time and urgency (Creative Reaction Labs Multiple dates, Mowris Reference Mowris2020). A major learning of RPD is that the process moves ‘slower’ and goes on community time. RPD moves at the speed of community and community relations or equitably negotiated time, shifting the leadership spectrum toward the community or the centre (equitable co-leadership). There may be times when urgency, not just a sense of urgency, may require an RPD team to move forward without the community fully represented, for instance, if there is danger or harm. However, the process becomes a CPD process if the urgency is determined by the professional designers. Additionally, danger and harm can be treated by immediate emergency responses outside of a design process, so designers must be wary of using such a reason to move ahead with a now CPD process without full, community-representative participation and leadership. In RPD, because the community is leading, the work only occurs without full community representation, if the community initiates and determines there is sufficient urgency, for example for community safety, to move forward without full representation. It is the community’s decision.

-

(ii) Community members outnumber non-community, professional designers on the design team.

What happens when the professional designers are members of the community and the dichotomy breaks down? In my experience, people holding multiple roles usually have a primary role affecting the leadership spectrum of the topology. If the designer-community member is facilitating the entire process, choosing methodologies, and leading, that person is serving primarily as a professional designer even though she carries community knowledge, tipping the leadership spectrum to the designer side. One can also embody the duality, primarily, as a community member. In such a case, the person may still be an expert in design from a modernist perspective, but they are allowing their expertise in cultural, lived, experiential, community knowledge to dominate, and they are placing their design expertise equal to and alongside all the other expertises that all other community members bring to the work. The community may or may not call on the person’s design skills or any other community member’s skills at any particular moment in their process. For instance, I am working on a project to redesign a parent-teacher association so that it is racially just. Since I am primarily acting as a community member, many people facilitate and my design skills do not dominate; my design skills are simply a set of skills offered alongside all the other skills and assets of all the other community members, tipping the leadership spectrum to the community side.

Because community members are full, equal members of the design team in RPD, community members have full participation and full co-leadership, two of three characteristics of design justice (Costanza-Chock Reference Costanza-Chock2018, Reference Costanza-Chock2020). Full accountability, the third characteristic, is a natural part of community design and community driven-design when the community initiates the project. In order to achieve community accountability when designers or design organisations initiate the project, the designers must divest of their power. Divestment is different from CPD which seeks to empower community members. Such empowerment paradoxically reinforces and maintains the hierarchy between privileged designers who have the power and position to empower others and the communities who have no or little perceived power apart from the designers. Instead, RPD invites designers to divest of their power which community members, then, assume. The design organisation receives a better design outcome, better attuned to the needs of the community who feels ownership over the design outcomes; and the community has more assumed, not granted, power, as a relational and systemic outcome. A type of power exchange occurs in RPD, not through empowerment, but through divestment of power.

Because the design process is iterative and, often, never complete, a project that begins as RPD may later switch to CPD or design injustice after the implementation stage or in future versions. Community participation and leadership can always end in the future, and designers and a design organisation may stop divesting of their power and reassume power. An example occurred in a recent project to redesign an international service-learning program. We practiced RPD with a community of students, and when it was time to implement our community design which fit the needs of the student community members, the nonprofit said no and took power away from the community of students (2018, 2022). The fact that a design organisation can reassume power represents a power imbalance that RPD does not eliminate whenever funding and resources from an organisation make a design project possible. Due to this possibility, there is a third characteristic that becomes more important after the design stage.

-

(iii) Community members retain and maintain accountability, leadership, and ownership of design outcomes and narratives about the design artefacts and work.

How are design team members accountable to the full community? How does decision-making work with a large group? Are there conflicts, differences of opinions? Who resolves this? These are all the wrong questions. I cannot answer them abstractly but only in the context of a specific project. The importance of the spectra remains: who initiates; who participates, who leads? The important question is not how accountability, decisions, and resolutions are determined. The important question is who determines or leads it. The community decides in an RPD process. Some projects may use a community review board; however, the mode of accountability must be culturally appropriate to the ontology of the community participating and what accountability means to them. The same is true with decisions. In many RPD projects, the community first decides how to decide so that when decisions are made using the chosen decision-making model, everyone accepts the result. Because of the importance of first choosing how to decide, deciding the decision-making model is usually done either by consensus, consent-based decision-making, or unanimity. There are RPD projects in relational communities in which we use a type of relational approach to the political process of decision-making. In short, instead of choosing the best option among the desires of individual people, the decision comes out of the union of purpose and relationship among community members in the same way that your body naturally makes decisions to send blood to a part of your body that is injured. I will share more in a future paper focusing on decision-making in RPD. Lastly, fear of open conflict is another way white supremacy is reinforced in design (Mowris Reference Mowris2020). There are many cultures that welcome or embrace conflict of ideas or thoughts, which can be healthy.

Radical participatory design goes further than research justice which equalises the value of experiential and lived knowledge of the community, the cultural knowledge of the community, and the institutional knowledge of organisations (Assil et al. Reference Assil, Kim and Waheed2015). Radical participatory values the lived and experienced community knowledge above the design and design process knowledge of the designers. For example, the value of a patient’s knowledge of their body and any problems with its functioning is different from the medical knowledge of the doctor (Dankl & Akoglu Reference Dankl and Akoglu2021). A person can listen to the signals of pain and discomfort from their body and act in ways to address certain problems without formal medical knowledge. However, it is very difficult for a medical professional to address a patient’s problem without the knowledge and information from the patient about what is happening, what hurts, how, when, and where it hurts. Likewise, it is possible for communities to design solutions to problems without any formal knowledge of design processes; communities have done this throughout the history of communities. However, it is very difficult for designers to design sustainable, accepted, and utilised solutions to problems without any community knowledge and experience. Radical participatory design recognises the value imbalance and has a bias towards the community’s experience, skills, and embodied knowledge.

The goal of RPD is transformational justice: research justice, design justice, and radically transformational justice. Conducting RPD is the just way to design. Research justice communities often say no policy, no research, ‘nothing about us without us.’ Justice is the goal and serves to relate and connect the other goals of CPD such as community perspectives, better design outcomes, and mutual learning. Justice automatically includes perspectives of the community because they are justly represented in the group of decision makers – designers; in fact, in RPD, the community members become designers. Justice automatically improves the design outcomes because the community who will use the designs are driving the process bringing their own expertise, desires, destinies, lived experiences, cultural knowledge, and futures to the design team. Justice moves beyond including perspectives to divesting the power of designers, while the community drives the process. Justice automatically creates mutual learning by putting diverse groups of people in touch with each other and creating connections between designers and community members. Mutual learning is only a goal from a CPD designer perspective. From the community perspective, mutual learning is a benefit, and the goal is more equitable outcomes and justice – full leadership, decision-making authority, participation, and accountability in a process that produces something for themselves and their community.

Because RPD is participatory to the core, RPD transforms the design process to an educational process. At every step of the way, professional designers may be creating educational experiences for the design team to learn and practice a skill before they use it in the next step. At the same time, according to the benefit of mutual learning, designers are also learning about the community not only from the research participants or testing with community members but from other research and design team members who are also community members. Research is transformed from a phase of activities in a design process to a mode of learning undergirding all phases of the design process. All design work becomes research and an educational experience through which designers learn.

Ultimately, RPD changes the role of the designer and the community member. The role of designer as facilitator is better than ‘designer as executive,’ but ‘designer as facilitator’ still maintains a hierarchy (Lee Reference Lee2008; Sanders & Stappers Reference Sanders and Stappers2008; Bang Reference Bang2009; Buys Reference Buys2019). Ultimately, RPD moves from ‘designer as facilitator’ to ‘community member as facilitator,’ decentering the designer. Even if an RPD process begins with a designer functioning as facilitator, community members would slowly, regularly, and increasingly begin to facilitate design activities, meetings, workshops, and sessions. There is too much power in the role of the facilitator – identifying interactions, moderating, facilitating cooperation, facilitating debate and conflict of ideas, introducing topics clearly or unclearly, facilitating the creation of ground rules or setting them, choosing processes, encouraging mindsets conducive for research and designing, managing the culture of design meetings, facilitating the search for information and identification of categories and problem definitions, helping to define evaluation criteria, summarising information, and managing relational dynamics (Ontkóc & Kotradyová Reference Ontkóc and Kotradyová2021, p. 3). Facilitation is never neutral. The application of all these skills represent power. In RPD, wherever there is power, designers must divest of it, while community members assume it. Facilitation is a key location of such power and a perfect example of an opportunity to divest of power. In all of my RPD work, community members are facilitating sessions and meetings. Even if they are not initially comfortable doing so or want to learn more about it, they go through the process of learning and practicing and doing specifically because, from a justice lens, the result of a design activity is different depending on who is facilitating.

In RPD, we use the model of ‘designer as community member.’ ‘Designer as community member’ means the gifts and skills the designer offers (design) are equal to and alongside all the skills and assets that all the other community members bring. The design skills of the designer are not greater than the gifts of the community members. The ‘designer as community member’ model shifts the leadership spectrum back toward the community. With the designer in the role of community member, the choice of research or design methodology opens up as the community, rather than the professional designer, facilitates the choice. The role of community members shifts not only to ‘community member as facilitator,’ but also ‘community member as designer.’

By bringing awareness and intention to the participatory nature and three spectra of design processes, we hope to reverse the intrapenetration of the larger system’s social field (Scharmer Reference Scharmer2009) into the micro-social field of the design process and create ‘suspended space.’ In design processes, we normally carry the thinking, hierarchies, separations, absencing, and power dynamics of the world into the spaces and processes we engage, whether it is playing in a playground, eating in a restaurant, applying for benefits, or working in an office. I call this intrapenetration. In the suspended space of an RPD process, we are creating a liberatory micro-social field where we suspend the class, power, and hierarchical differences of the world and first create interpenetration. In interpenetration, not only does the larger system’s social field affect our design process’s social field, but the social field of the design process begins to affect and make small changes to the system’s social field. For example, in my project to design a racially just PTA, we try to embody racial justice on our design team in our design work. Remnants of this more just, whole, self-decentring social field of our design sessions tend to cross the boundary and linger outside of the design process as we interact with each other in the neighbourhood and the school. Our goal is to create suspended space in our RPD process and begin to extend that suspended space for longer periods of time until we switch to extrapenetration where the micro-social field of the design process is only affecting the larger system’s social field. In other words, this intentional, awareness-based meta-methodology slowly begins to alter the system.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we discussed the various problems and conflicting definitions, contexts, and goals of the term PD. To clarify what I mean when I use the term, I have introduced a new term, a meta-methodology called RPD.

We covered the history of PD and PR, highlighting that communities have always engaged in PD and PR since the formation of communities; any history of PD is nonsensical as there was no historical start of PD apart from the historical formation of communities. Through the lenses of initiation, leadership, and participation, we explored the typology of participation and what people mean by the term ‘participatory.’ Radical participatory design, regardless of who initiates the project, is one in which the community both drives and leads the process, outnumbers the professional designers and researchers, and participates in all activities, phases, and interactivity work, fully owning the outcomes and artefacts as well as the narratives around those outcomes. In an RPD process, we discard the ‘designer as facilitator’ model and move to the ‘designer as community member,’ ‘community member as designer,’ and ‘community member as facilitator’ models representing a power exchange.

There are three main areas of further work to share. In part II of this paper, we will explore other parts of RPD (Udoewa Reference Udoewa2022a ). For instance, why should anyone use RPD? What is the benefit? While this paper discusses the motivation and meta-methodological framework and models, in part II of this paper, I continue expanding about the RPD meta-methodology including the benefits and how RPD connects to futures design, systems practice, and pluriversal design, as well as community-centred, society-centred, life-centred, and planet-centred design. I will discuss the relationship between RPD and empathy, comparing it to other design and awareness-based ways of achieving empathy. I will elaborate on the difficulties of RPD as well as tips to handle the difficulties. I will explore the ethics and evaluation of RPD in order to determine if a PD process was radically participatory and the transformation that occurs when it is. Lastly, I will further discuss organisational resistance to RPD and organisational ways to encourage its use. All of these components – benefits, empathy, ethics, evaluation, transformation – are all important characteristics of RPD and helpful in characterising RPD so as to compare it to other namologies (studies, perspectives, or ways of designing) and in assessing the radicality of participation of any particular project (Ibibio Generations n.d.).

A second possible further direction is to more fully develop an understanding and framework of relational design of which RPD is an instance. This explicit framework is called Relational Design with capital letters. By Relational Design, I mean explicit ways of transforming each of the transactive, subject/object, third-person knowing steps of a generic design process into a relational one. It can happen naturally in an RPD process. At the same time, it is possible for others to use an RPD process and engage in a process dominated by third-person knowledge-seeking (though hopefully checked by lived experiential, spiritual, and cultural knowledge on the team). I am currently experimenting with a more explicit relational process with other community members and hope to share more about Relational Design in the future.

A third area of work is the political ecology of decision-making in design, through a relational approach, as mentioned earlier. There are ways in which RPD communities make decisions not from an ontology of individualism, nor from one of a network of individuals, but from a radically relational approach, relationality to the root. Instead of weighing the individual preferences of individual entities to make a decision, decisions are automatically sensed, known, or made from an ecological approach in which everyone is consciously aligned with a system purpose as well as their role in the system. These future directions will help elucidate other components of RPD, as well as create a more enriched picture of the many forms it takes in practice.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2022.24.