Across fields addressing child and family development, the study of parenting has had a deep, rich, and sometimes controversial history. From notions of good enough parenting (Winnicott, Reference Winnicott1960) to intensive parenting (Schiffrin et al., Reference Schiffrin, Godfrey, Liss and Erchull2015) to the evidence-based straightforward contention that parenting matters (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2005), parenting carries a substantial load in determining the quality of children’s development and family well-being. Few experiences can match the many joys inherent in parenthood, but likewise few experiences present the frequent, often daily challenges that parenting does. The stresses associated with parenting have proven to be complex, nuanced, multiply determined, and broadly consequential for children and parents alike (Crnic & Coburn, Reference Crnic, Coburn and Bornstein2019).

Parenting stress connections to problematic child behavior and dysregulated emotion are ubiquitous (Barroso et al., Reference Barroso, Mendez, Graziano and Bagner2018), as are associations with parental distress as well (Thomason et al., Reference Thomason, Volling, Flynn, McDonough, Marcus, Lopez and Vazquez2014). But the nature of these associations, the mechanisms through which these associations emerge, the directions of effect involved, and the complex pathways of influence that operate across critical developmental transitions are key to better understanding the salience of parenting stress to risk for psychopathology. Driven by developmental psychopathology frameworks, some answers have begun to emerge but there remains much to be explained in the way that parenting stress operates to influence child, parent, and family well-being.

In many ways, the growing focus on parenting stress in developmental and clinical literatures paralleled the emerging emphasis in and adoption of developmental psychopathology perspectives in understanding risk and resilience processes. With the publication of the 1984 special issue in Child Development, Dante Cicchetti not only explicated the need for a multidisciplinary integration of effort to explore normative developmental processes in atypical populations, he curated a series of papers that laid the early framework for the developmental psychopathology perspective to flourish and become the predominant paradigm organizing the study of child and family psychopathology. In myriad publications to follow, as well as through his extraordinary career editorship of Development and Psychopathology, Dante (if I may be allowed the use of the familiar) has refined, expanded, and reified the field of developmental psychopathology to guide scientific inquiry in this important domain of human experience. His emphasis on the ways that normative development and atypicality are mutually informative, as well as concepts of continuity and discontinuity, equi- and multifinality, and the importance of identifying adaptive resilient pathways among many others have become the basic tenets of the science. As such, these concepts and frameworks form the basis of the most critical work on parenting stress, directing it away from simple main effect modeling to seek more sophisticated understandings of the multiplicity of ways that parenting stress may play a part in emerging disruption in the child and family system.

The volume of work on parenting stress over the past several decades is remarkable in both mass and scope. An exhaustive overview of this work is not the intention of this paper, and broader reviews can be found elsewhere (Crnic & Coburn, Reference Crnic, Coburn and Bornstein2019; Deater-Deckard & Panneton, Reference Deater-Deckard and Panneton2017; Holly et al., Reference Holly, Fenley, Kritikos, Merson, Abidin and Langer2019). But there are a number of critical conceptual and empirical issues, driven by developmental psychopathology perspectives, that merit specific consideration in further explicating the processes and mechanisms though which parenting stress is complicit in the emergence of dysregulated and problematic functioning in parents, children, and families. Specifically, clearer conceptual frameworks, a stronger focus on developmental differentiation, and adoption of a more systemic perspective are needed to influence the next generation of research on parenting stress.

Conceptual modeling

Current perspectives on parenting stress involve a set of core assumptions that have driven most of the recent research, and reflect the impact that a developmental psychopathology perspective has brought to bear. Conceptualizations of parenting stress have diverged to focus on either more problematic or more normative contexts (Crnic & Coburn, Reference Crnic, Coburn and Bornstein2019; Deater-Deckard & Panneton, Reference Deater-Deckard and Panneton2017), although these approaches may be more complementary than competing. The nature of change over time and the ways that developmental period may differentiate parent stress processes are important central issues, as is the identification of mechanisms by which parenting stress exerts its influence across a variety of adaptational outcomes for children, parents, and families. The degree to which parenting stress is actually more systemic than child-specific is an unexplored issue that begs further consideration, as broader family system perspectives are incorporated into ongoing parent stress considerations. These issues are explored briefly below.

Differentiating stress in parenting contexts

Precision in defining constructs may be a somewhat underappreciated principle of developmental psychopathology, but it is critical to understanding and clarifying the basic concepts involved with parenting stress. In fact, differentiating parenting stress from stressed parenting is especially important as these constructs have been conflated to some extent in previous explorations of parenting stress (Crnic & Ross, Reference Crnic, Ross, Deater-Deckard and Panneton2017; Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard2004), even though there are multiple differentiating characteristics and relations to child, parent, and family functioning (Crnic & Coburn, Reference Crnic, Coburn and Bornstein2019). Stressed parenting does not necessarily imply that the stress experienced is sourced from within the parenting context. Rather, it is often more extrafamilial in nature (e.g. job-related, economic, social-relational) and sometimes familial (e.g. marital), but spills over into parenting contexts. Extrafamilial challenges and conditions are important stress functions with a compelling history in developmental risk modeling (Garmezy and Rutter, Reference Garmezy and Rutter1983), have demonstrated implications for child and adolescent well-being (Conger et al., Reference Conger, Patterson and Ge1995; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Martin, Trejos-Castillo and Mastergeorge2024), and have been associated with adverse impacts on parent functioning and mental health (Newland et al., Reference Newland, Crnic, Cox and Mills-Koonce2013). Parenting stress, in contrast, focuses specifically on the context of parenting itself, and reflects the adverse reaction to demands of the parenting role (Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard1998).

There is both conceptual and empirical evidence to support the idea that stressed parenting and parenting stress are differentially related to child and family functioning, even though they may share some influence within the family (Crnic et al., Reference Crnic, Gaze and Hoffman2005). Indeed, it appears that parenting stress has stronger associations to specific child, parenting, and family attributes than do extrafamilial stresses. Although both stressed parenting and parenting stress represent stress contexts with potentially adverse implications for families, clarity in separating the two contexts brings a precision necessary for differentiated modeling. Added precision can advance empirical approaches that better identify the mechanisms through which parenting processes may be associated with emerging psychopathology.

Modeling process functions

Process model

Main effect modeling was reflected in the majority of early studies of parenting stress and uniformly found clear associations between parenting stress and child behavior problems, as well as parent distress (Crnic & Low, Reference Crnic, Low and Bornstein2002). As developmental psychopathology perspectives emerged, questions regarding the mechanisms that underlie these relations began to take shape. Direction of effect in the relations between parenting stress and problematic child and parent functioning was questioned, as was the nature of the pathways of influence that might indicate whether the connections were indirect or direct (Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard1998; Reference Deater-Deckard2008). Too, parenting stress was found to operate at times other than as a predictive risk factor or problematic outcome in pathway models, as it was sometimes considered as a mediator or moderator of connections between parenting and some adaptive state (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Woods-Jaeger and Borelli2021; Gordon & Hinshaw, Reference Gordon and Hinshaw2015; Whitson & Kaufman, Reference Whitson and Kaufman2017). The myriad roles that have been hypothesized and explored are not especially surprising, as despite the prolific empirical work on the construct, there exists no single, unifying, coherent, conceptual model to guide research or explore the function of parenting stress within a developmental psychopathology framework.

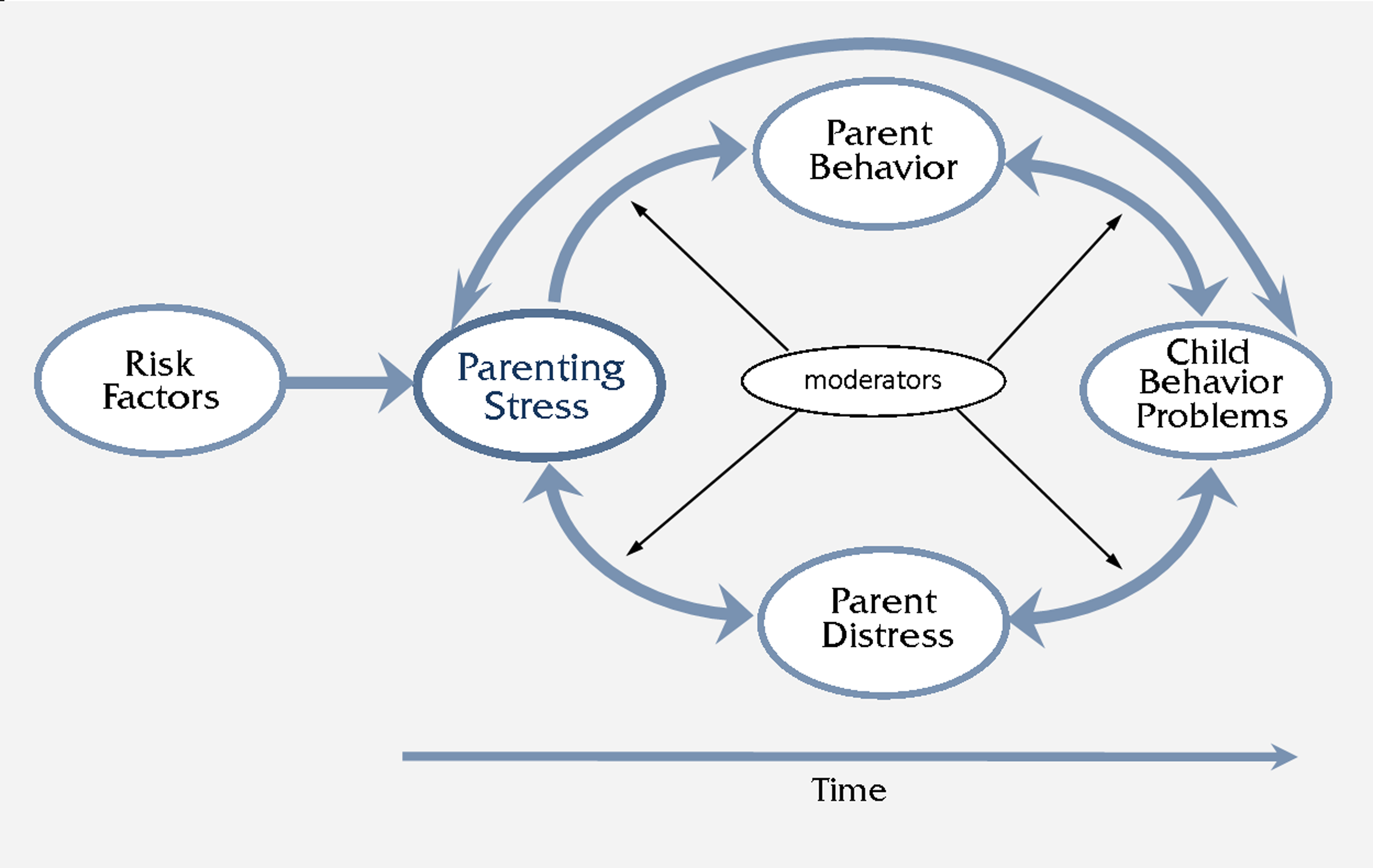

Attempts to advance a single model to account for the multiplicity of ways that parenting stress operates to contribute to emerging child, parent, and family problems may well prove to be folly, given the many complexities involved (intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, contextual, neurobiological, etc.). Nevertheless, an attempt to explicate a basic process model is offered (see Fig. 1) that attempts to broadly capture the moderated mediational pathways of influence reflected both in the work to date as well as the multiple facets still in need of attention. Taking as a starting point Abidin’s (Reference Abidin1992) suggestion that parenting stress influences child functioning indirectly through its effect on parenting, the model extends that core process to consider that risk creates vulnerability to parenting stress, that parental psychological distress functions as a bidirectional contributor, that moderators operate at each stage of the core relations, and that the basic nature of the connections are recursive and transactional.

Figure 1. Parenting stress process model.

Direction of effect

Most important within the parenting stress model are issues involving directionality and pathways of influence that address mediated and moderated processes that influence emerging problems over time. Despite the fact that parenting stress and adverse functioning have been consistently and moderately (sometimes strongly) connected, it simply wasn't clear that the process was characterized by a single unidirectional path in which higher levels of parenting stress lead to more problematic later functioning. Certainly there was reason to speculate that child behavior problems or parental psychological distress might also eventuate in heightened experiences of parenting stress, as Deater-Deckard (Reference Deater-Deckard2008) had made clear. Longitudinal research has offered some support, albeit nuanced, for the child-effect model (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Mares, Otten, Engels and Janssens2016) as well as for parent psychological distress (i.e. maternal depressive symptoms) to predict subsequent reports of parenting stress (Thomason et al., Reference Thomason, Volling, Flynn, McDonough, Marcus, Lopez and Vazquez2014). It seems apparent that there is no single direction of effect that is operative; rather reciprocity and bidirectionality are inherent in the connections over time (Neece et al., Reference Neece, Green and Baker2012), the accumulation of which can escalate risk of adaptive problems for children and parents.

Parenting stress and change

Parenting stress is often treated as though it is a static construct; seemingly invariant across time in both degree and nature. Only a relatively small number of studies have assessed whether parenting stress changes from one time to another (e.g. Crnic et al, Reference Crnic, Gaze and Hoffman2005; de Maat et al., Reference de Maat, Jansen, Prinzie, Keizer, Franken and Lucassen2021; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Mares, Otten, Engels and Janssens2016; Williford et al., Reference Williford, Calkins and Keane2007), often finding that parenting stress decreases over time, but the decreases are often nuanced or conditional (Östberg et al., Reference Östberg, Hagekull and Hagelin2007). From infancy to toddlerhood (Crnic & Booth, Reference Crnic and Booth1991), or under conditions of child developmental risk (Gerstein et al., Reference Gerstein, Crnic, Blacher and Baker2009), parenting stress may actually increase over time. Regardless, normative approaches to parenting stress would posit that parenting stress should vary, even on a daily basis. The accumulation of these minor everyday stresses can reach a threshold that eventually exceeds parental ability to manage that load. In support of such cumulative models, Sturge-Apple et al. (Reference Sturge-Apple, Skibo, Rogosch, Ignjatovic and Heinzelman2011) identified a pattern of parenting where in the context of accumulating stresses, allostatic systems have difficulty regulating the stress associated with the challenges of parenting children who are distressed.

The question of whether accumulating parenting stress and the microsocial processes involved can act as change agents within the family (Patterson, Reference Patterson, Garmezy and Rutter1983), deflecting what may begin as positive relationships toward more agonistic ones, remains a critically important question. The answer, however, remains a relative unknown. The longitudinal, naturalistic (in home), and ecological momentary assessment research most necessary to demonstrate such change and its consequence for maladaptation has yet to be done. This is an important target for future efforts with innovative methodological approaches to expand the implications of parenting stress processes to adaptational outcomes in families.

Indirect influence

As noted above, most conceptualizations of the connections between parenting stress and child behavior problems suggest that the connections were likely indirect and mediated by parenting behavior (Abidin, Reference Abidin1992; Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard1998). However, the evidence in support of mediated pathways of influence between parenting stress and child adjustment is at best rather inconsistent. Some work has found evidence in support of the expected mediated path (Deater-Deckard & Scarr, Reference Deater-Deckard and Scarr1996; Putnick et al., Reference Putnick, Bornstein, Hendricks, Painter, Suwalsky and Collins2008), while more often mediated relations have proved elusive (de Maat, et al., Reference de Maat, Jansen, Prinzie, Keizer, Franken and Lucassen2021; Huth-Bocks & Hughes, Reference Huth-bocks and Hughes2008; Mackler et al., Reference Mackler, Kelleher, Shanahan, Calkins, Keane and O’Brien2015). Data to support parent psychological distress as a mediator is likewise hard to find, but more so because of the relative dearth of studies rather than null findings. Although results of mediational analyses to date have been disappointing with respect to support for parenting stress theory, it is far too early to dismiss parenting behavior and psychological well-being as potential mediators of the relations between parenting stress and child adjustment. Limitations in design, measurement, and method have conspired to limit the ability to adequately demonstrate the presence of these mechanisms or pathways. Certainly, there is wealth of data to support the connections between parenting stress and a variety of positive and negative parenting behaviors as well as parental depression and anxiety (Crnic & Coburn, Reference Crnic, Coburn and Bornstein2019). Likewise, connections between these parenting factors and child adjustment are well established (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2019; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Simon, Shamblaw and Kim2020). As such, expecting parenting stress pathways of influence to operate through parent functioning is logically and conceptually compelling. More precise and developmentally specific research foci should help illuminate these mechanisms, and the conditions under which they occur.

It may also be that such pathways are masked by unmeasured moderators that buffer or protect against adverse effects of stress. Indeed, some efforts to explore moderation mechanisms in parenting stress have suggested that moderated processes are indeed operative. Barroso et al., (Reference Barroso, Mendez, Graziano and Bagner2018), in a meta-analysis of parenting stress studies with clinical samples, found that parenting stress connections to child adjustment were moderated by child sex as well as the presence of clinical conditions. Moderation between parenting stress and related model factors has also been reported for a range of other factors including parental self-efficacy (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016), child self-regulation (Tsotsi et al., Reference Tsotsi, Broekman, Sim, Shek, Tan, Chong, Qiu, Chen, Meaney and Rifkin-Graboi2019), coparenting and the parenting alliance (Camisasca et al., Reference Camisasca, Miragoli and Di Blasio2014; Turgeon et al., Reference Turgeon, Lonergan, Bureau, Schoppe‐Sullivan and Lafontaine2023), parental empathy (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Dong and Chen2022), child cognitive control (Raffington et al., Reference Raffington, Schmiedek, Heim and Shing2018), and maternal positive affect (Smith and Stephens, Reference Smith and Stephens2018) among multiple others. Identifying exactly where within the proposed model these moderators may truly operate needs to be more clearly investigated, but building a comprehensive and cohesive understanding of parenting stress mechanisms in the emergence of maladaptation or psychopathology requires more attention to complicated mediated and moderated pathways of influence across time.

Needed focus on development

Although research on various aspects of parenting stress has proliferated over the past few decades, it has remained strangely a developmental in its emphasis. With notable exceptions (e.g. Gerstein et al., Reference Gerstein, Crnic, Blacher and Baker2009; Putnick et al., Reference Putnick, Bornstein, Hendricks, Painter, Suwalsky and Collins2010; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Mares, Otten, Engels and Janssens2016; de Maat et al., Reference de Maat, Jansen, Prinzie, Keizer, Franken and Lucassen2021; Williford et al., Reference Williford, Calkins and Keane2007), scant attention has been paid to understanding exactly how parenting stress may change over time (stability), and the ways that parenting stress may differ across different developmental periods (continuity). The parenting challenges of infancy and early childhood are not the same as the challenges of adolescence. Indeed, it is likely that the specific stressors of parenting may change even though the absolute amount of stress perceived may be relatively stable, raising important questions about construct continuity. Curiously, few cross-sectional studies that measure parenting stress in groups of parents with children at different developmental periods have been done; although there is now evidence that suggests potentially important developmental differences (Kochanova et al., Reference Kochanova, Pittman and McNeela2022). Some longitudinal studies have been employed, but typically they are relatively short-term and rarely cross important developmental transitions (see Putnick et al., Reference Putnick, Bornstein, Hendricks, Painter, Suwalsky and Collins2010; Rantanen et al., Reference Rantanen, Tillemann, Metsäpelto, Kokko and Pulkkinen2015; and Stone et al., Reference Stone, Mares, Otten, Engels and Janssens2016 for exceptions).

Given the field’s long held interest in the processes involved in the transition to parenthood and the salience of early childhood functions for later developmental competencies, early childhood was a prime period for studying parenting stress. Consequently, much of what we know about main effect and more developmentally sophisticated explanatory models comes from this age period (Crnic & Coburn, Reference Crnic, Coburn and Bornstein2019). Nonetheless, studies of parenting stress in middle childhood (e.g. Mackler et al., Reference Mackler, Kelleher, Shanahan, Calkins, Keane and O’Brien2015; Östberg & Hagekull, Reference Östberg and Hagekull2013; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Mares, Otten, Engels and Janssens2016) and adolescence a (e.g. de Maat et al., Reference de Maat, Jansen, Prinzie, Keizer, Franken and Lucassen2021; Kochanova et al., Reference Kochanova, Pittman and McNeela2022; Putnick et al., Reference Putnick, Bornstein, Hendricks, Painter, Suwalsky and Collins2008) are available and not only support the salience of parenting stress to parent, child, and adolescent functioning across various adaptational domains, but suggest that parenting stresses may operate differently across developmental periods.

Developmental psychopathology implies a lifespan focus, but studies of parenting stress do not typically extend beyond parents of adolescents. The one exception is the study of parents of adult children with developmental disabilities, many of whom live at home or require adult assistance to manage their daily lives (Hill & Rose, Reference Hill and Rose2010). Nevertheless, the study of parenting beyond the developmental period has been identified as a neglected, but important area for research (Kirby & Hoang, Reference Kirby, Hoang, Sanders and Morawska2018), especially with respect to its implications for parental well-being. The nature of the parenting stresses that may be involved are largely unknown, but parents don’t stop being parents once their children have grown and leave home. The quality of the parent-adult child relationship, worry about the adult children’s well-being, and even approaches to grandparenting could be potential sources of parenting stress that connect with experiences of parental distress and broader family conflict as parents age.

Parenting stress is systemic

It is interesting that in many ways parenting stress is considered to reflect an individual or at best a dyadic construct; that is, it represents one parent’s appraisal of the stressfulness associated with a specific child. Study samples typically focus on a specific age group of children, and if parents have more than one child within that age group, they are asked to choose one as the object of their reports. Deater-Deckard (Reference Deater-Deckard1998) suggested some time ago that parenting stress may be “child-specific” within families with multiple children, and presented some evidence in support of this contention (Deater-Deckard et al., Reference Deater-Deckard, Smith, Ivy and Petril2005). The wealth of data that has emerged in support of parenting stress as an important developmental construct reflects this child-specific approach.

Certainly, the evidence seems clear that parents can perceive their sibling children differently along any number of dimensions, and those differential perceptions can have implications for parent-child relationships over time (Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, McHale, Whiteman and Bornstein2019). Nevertheless, an argument can be made that parenting stress might better be conceived as systemic rather than, or in complement to being child-specific and dyadic. Although individual children within a family may be viewed differently, and some siblings considered more stressful than others, it seems as though parenting stress might better be considered to reflect a more wholistic response to the range and depth of the parenting experience across all children within a family at any one moment and especially across time.

Family systems theory suggests that all members of the family are in fact part of a mutually responsive and integrated whole (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, O’Brien, Blankson, Calkins and Keane2009). It is also the case that whether one adopts the more problem-oriented parent-child relationship framework (Abidin, Reference Abidin1992) or the more normative daily hassles model (Crnic & Greenberg, Reference Crnic and Greenberg1990) of parenting stress, the conceptual and measurement models of each are not necessarily, nor entirely, child-specific. In families with multiple children, it is likely difficult for parents to fully compartmentalize their stress to individual children, and the stress they experience in the parenting role would logically reflect some aggregate of their experience across the whole of the family. Although not a direct test of this assumption, several studies have demonstrated that a larger number of children in a family is associated with reports of higher parenting stress (Crnic & Greenberg, Reference Crnic and Greenberg1990; Viana & Welsh, Reference Viana and Welsh2010). Even if parenting challenge is perceived differentially by child at any single moment or consistently over time, the likelihood of spillover into other parent-child relationships seems high. Such spillover effects would likely increase perception of parenting stress as a whole. Of course, it is also possible that siblings perceived as less stressful could serve as compensatory mechanisms for parents struggling with more difficult siblings, but those are further systemic questions that need to be addressed. Regardless, moving beyond the individual child model of parenting stress for families with more than one child could be especially informative, not only conceptually, but in better understanding the ways that cumulative stress functions may operate for parents.

The systemic functions of parenting stress extend as well to other family subsystems that are integral to child, parent, and family well-being and that serve as potential mediating or moderating mechanisms for emergent problems. Marital relationships have been implicated as determinants, consequences, or mediators of parenting stress (Camisasca et al., Reference Camisasca, Miragoli and Di Blasio2014, Ponnet et al., Reference Ponnet, Mortelmans, Wouters, Van Leeuwen, Bastaits and Pasteels2013; Robinson & Neece, Reference Robinson and Neece2015), as have coparenting processes (Camisasca et al, Reference Camisasca, Miragoli, Di Blasio and Feinberg2022; Delvecchio et al., Reference Delvecchio, Sciandra, Finos, Mazzeschi and Di Riso2015; Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Jones, Kan and Goslin2010; Park et al., Reference Park, Bellamy, Speer, Kim, Kwan, Powe, Banman, Harty and Guterman2023; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Reference Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee and Kamp Dush2016). Further, cross-over effects, wherein one parent’s perceived stress influences the other parent’s (or caregiver’s) stress or functioning across domain have received relatively little attention, and findings to date have been somewhat inconsistent as to whether cross-over effects are present in caregiving (de Maat et al., Reference de Maat, Jansen, Prinzie, Keizer, Franken and Lucassen2021). It may be that cross-over effects are domain specific, affecting some areas of social and family function but not others (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, O’Brien, Blankson, Calkins and Keane2009), or are dependent on the presence of some other risk in the family such as developmental disorder in the child (Gerstein et al., Reference Gerstein, Crnic, Blacher and Baker2009; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Szczerepa and Hauser-Cram2016). Studies contrasting mother and father parenting stress show both shared aspects and similarities as well as ways in which mothers and fathers differ (Crnic & Booth, Reference Crnic and Booth1991; de Maat et al., Reference de Maat, Jansen, Prinzie, Keizer, Franken and Lucassen2021; Ponnet et al., Reference Ponnet, Mortelmans, Wouters, Van Leeuwen, Bastaits and Pasteels2013; Putnick et al., Reference Putnick, Bornstein, Hendricks, Painter, Suwalsky and Collins2010) mapping on to the more systemic findings as well. Regardless, systems approaches are integral to a developmental psychopathology perspective, and demand that mothers and fathers, or any parenting partner relationships, and all children be accounted for in understanding the ways in which parenting stress may operate to influence emerging maladaptation.

Conclusions

Parenting stress has emerged as a construct within developmental psychopathology that has rather impressive breadth with respect to the role it can play in conceptualizations of child, parent, and family adaptation across time. It is a role that spans elements of risk, consequence, and intermediary process within and across developmental periods. Much has been learned over the past three decades, particularly with respect to the challenges involved in amassing evidence in support of the complex mechanisms hypothesized to underlie the parenting stress pathways that can lead to maladaptation. Much of the accrued knowledge can be attributed to the adoption of developmental psychopathology perspectives. And while we know now that parenting stress matters, there remain ongoing needs to further refine the concept, interrogate further its developmental nature, identify the specific conditions under which mediated and moderated functions occur, and better consider the systemic qualities of the construct.

As the years have unfolded since the 1984 special issue, we rightfully credit Dante with the intellectual stewardship of the developmental psychopathology perspective, leading the focus on an ever growing panoply of core constructs, tenets, and methods that forge increasingly sophisticated insights into psychopathology. Impressive as this is, it belies another way that Dante has truly been responsible for the growth of a field. He has done more to influence the careers of an enormous number of developmental scientists than can be imagined. At every level of training, and with colleagues across the spectrum of advancement through the academy, Dante has given willingly of his time and his reputation to promote the careers of others. Many of us have incredible stories we can tell, whether those involve studying under his mentorship or engaging at any level of collegial or more personal relationships. Dante’s sincerity and genuine efforts to enthusiastically promote the career development of others is unique among scholars in his position, and this commitment to career success for others has been instrumental in creating a substantial cohort of scholars who embrace the developmental psychopathology perspective in the science they pursue.

Dante stood on the shoulders of early disciplinary giants, scholars he called systematizers (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1984), to see well beyond disciplinary boundaries to envision what a commitment to integrating multiple disciplinary ideas could mean for better understanding psychopathology across the lifespan. The development of the field of developmental psychopathology can be likened to the organizational model (Werner, Reference Werner1948) that was so germane to early conceptual underpinnings of the field. Developmental psychopathology grew as a function of increasing differentiation and hierarchical integration of concepts, constructs, and methods that facilitated the emergence of sophisticated new perspectives and methods. That growth continues, and Dante has provided the epistemological map for the next generation of developmental scholars in psychopathology to now stand on his shoulders and chart the path ahead.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

None.