Introduction

A disaster is defined as an event which overwhelms the response capability or resources of a community. Reference Dervay1 The nature of these sometimes large, unpredictable events, may require unconventional, and perhaps more complex procedural responses. This emphasizes the importance of an emergency preparedness plan before a major disaster occurs.

Large scale disasters create additional strains on health care systems which are often already operating at near-capacity levels in terms of physical space, diagnostics, and human resources. Impacts on medication supplies and supply chains have been documented in several past disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic has also provided challenges not typically seen with more localized disaster events. Integration of pharmacy services is an important component of disaster preparedness to ensure that selection, availability, and storage of additional medication supplies are appropriate for the treatment of patients at the time of the disaster and for a significant duration of the recovery period. Reference Krajewski, Sztajnkrycer and Báez2

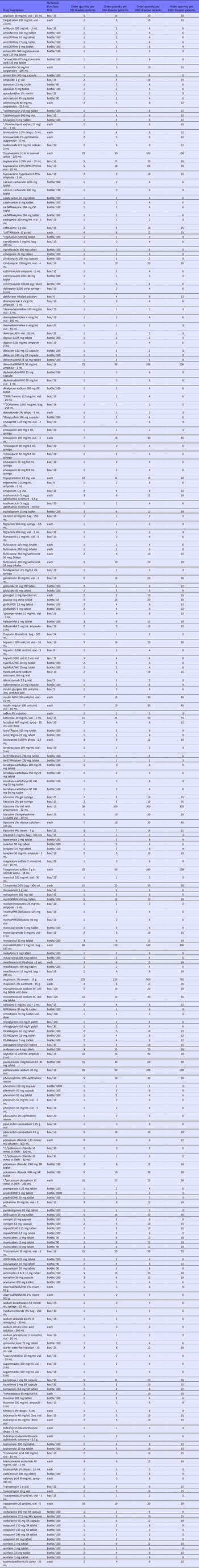

Hospitals should identify disaster potentials for their location when developing an appropriate disaster plan. Reference Lynx3 Examples of disasters which can be considered during this process are listed in Table 1 and are often classified as natural, man-made, or technological. Reference Dervay1,Reference Kaji, Langford and Lewis4 The potential for a natural disaster depends on factors such as geographical location, season, and climate variations. Reference Dervay1 Of high concern to Vancouver Island and the Pacific Coastal Region is a magnitude 7.1 to 9.0 Richter scale earthquake and resulting tsunami, which are predicted to occur along the Cascadia Subduction Zone within the next 50 years. Reference Goda, Zhang and Tesfamariam5,6 Preparing for a major earthquake on Vancouver Island is thought to also meet the needs of many other disasters that can occur within this region.

Table 1. Potential disaster scenarios Reference Dervay1,Reference Mardan, Amalnik and Rabbani34–Reference Shaluf36

In preparation for a disaster, some medical needs may be predictable according to the disaster type (e.g., musculoskeletal injuries post-earthquake) Reference Klitzman and Freudenberg7–Reference Beaglehole, Bell, Frampton, Hamilton and McKean13 ; however, some patient presentations following a disaster may be less intuitive. Reference Nufer and Richards9,Reference Howe, Victor and Price14–Reference Tan, Lee, Chang, Ang and Seet16 Descriptions of past disasters suggest patients present to healthcare facilities for both acute and chronic medical conditions following a disaster. Reference Arrieta, Foreman, Crook and Icenogle12,Reference Howe, Victor and Price14,Reference Miller and Arquilla17–Reference Okumura, Nishita and Kimura21 These observations may be helpful in anticipating medications required during the initial emergency response. Reference Howe, Victor and Price14,Reference Rosenthal, Klein, Cowling, Grzybowski and Dunne22

Establishing a disaster plan with medication suppliers prior to a disaster event is critical. Federal assistance in the form of medication supplies will likely be delayed and the list of medications available through this source is not widely known. Reference Equipment23–25 Given that community pharmacies are privately owned and separate entities from public health care in Canada, hospitals cannot expect access to medication supplies from these businesses during a disaster event. It may also be advantageous in reducing emergency department (ED) presentations if these pharmacies can provide medications to patients.

Island Health is a publicly funded health authority which provides healthcare services across Vancouver Island and Mount Waddington Coastal regions of British Columbia. Over 850000 people are serviced by more than 150 healthcare facilities including hospitals and other healthcare centres. The aim of this paper is to provide healthcare professionals with Island Health Authority’s emergency preparedness strategy which describes the selection, over-stocking, and procurement of key medications for hospitals in preparation for a disaster event on Vancouver Island.

Island Health Authority disaster preparedness strategy for medication supplies

Creating a priority medication list for disaster preparedness

To determine a list of medications that Island Health Authority could need in a major disaster, normal medication usage patterns were first identified before clinicians selected the high priority medications for a disaster response.

While imperfect, this health authority’s best approximation of drug usage was based on purchasing data. A 3-year report was generated for the years 2017, 2018, and 2019 to identify drug names, the base unit of measure (BUOM), amounts purchased in each year, and the gross total for the 3 years. A preliminary list of medications was then selected by the emergency pharmacist based on the likelihood of increased usage in a disaster and the potential for clinical harm should these medications run out. Lessons from previous literature, and resources such as the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines and the Interagency Emergency Health Kit, were used to assist in determining the key medications that should be in the disaster plan. 26,27 Additional subjective recommendations were provided by the emergency pharmacist to include medications that should also be considered by the broader stakeholder group.

Once the preliminary list was created, 3 medication stocking strategies were drafted. Category A consists of medications that should be overstocked and have an immediate purchase order at the time of initiating the disaster plan. Depletion of category A medications is subjectively considered to be associated with a higher likelihood of patient harm and/or a significant impact on patient flow in the healthcare system within the first 72 hours post-disaster. Category B requires an immediate order of these medications if a disaster occurs, but no perpetual overstocking. Selection of these medications was subjectively based on the potential for patient harm or a significant impact on patient flow within a week. Category C consists of all other medications considered low risk for patient harm or bottlenecking of healthcare services should they become depleted. These medications are ordered per normal procedures (i.e., as supplies reach minimum quantities without a pre-emptive purchase order or overstocking). Additional factors in determining the strategy for each medication included the likelihood of the medication to be easily available to patients within the community and possible altered usage during a disaster.

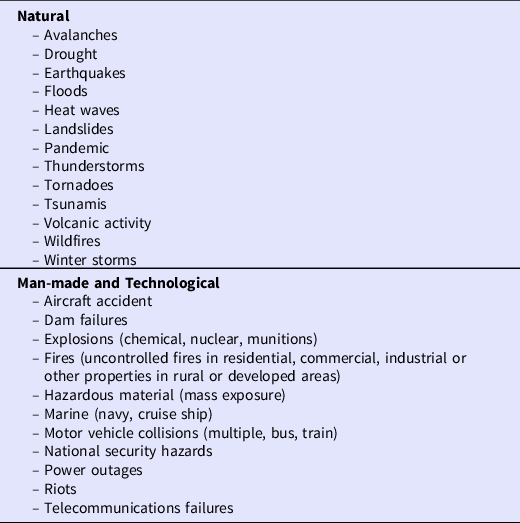

Following the preliminary categorization of medications, stakeholders including physicians and clinical pharmacy specialists from emergency, critical care, cardiology, ophthalmology, anaesthesiology, psychiatry, pediatrics, neonatology, internal medicine, nephrology, and infectious disease were asked to review all 143 drugs in category A, all 238 drugs in category B, and 220 of 2816 drugs in category C. The subset of category C medications was selected by the emergency pharmacist for broader review to determine if these medications should continue to be excluded from categories A and B. Stakeholder feedback including potential additions to the list, was then used to finalize the disaster strategy for each item. In situations with conflicting recommendations, a panel of 4 clinical pharmacy specialists reached a consensus on the final disaster medication list. Order sheets were then created for use at the time of a disaster (Tables 2, 3, and 4). The final numbers were 159 drugs in category A, 254 drugs in category B and the remaining drugs in category C.

Table 2. Medications listed in the controlled drug order form for Island Health Authority during a disaster

* Category A medications requiring a 6–12-week overstock target for pre-disaster stock on hand (may vary per site). All other medications listed are deemed Category B medications. Medications not listed are considered Category C medications.

Table 3. Medications listed in the non-controlled part 1 drug order form for Island Health Authority during a disaster

* Category A medications requiring a 6-12 week overstock target for pre-disaster stock on hand (may vary per site). All other medications listed are deemed Category B medications. Medications not listed are considered Category C medications.

† Medications ordered through alternate vendors

Table 4. Medications listed in the non-controlled part 2 drug order form for Island Health Authority during a disaster

* Category A medications requiring a 6-12 week overstock target for pre-disaster stock on hand (may vary per site). All other medications listed are deemed Category B medications. Medications not listed are considered Category C medications.

† Medications ordered through alternate vendors

§ SWFI = sterile water for injection

¶ D5W = dextrose 5% in water

Defining overstock quantities

Current pharmacy inventory levels provide a 2-to-4-week supply. Informal communications with a small selection of larger hospitals in different geographies within Canada (1 in each of British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland, New Brunswick, and the Yukon) suggested that a usual range of 2-to-4 weeks inventory level is not uncommon. However, hospitals in Quebec are reported to have inventory levels lasting 9 to 10 weeks for most drugs. A decision was made to target a 6-to-12 weeks supply of category A drugs within Island Health if possible. Prioritization of these includes analgesics, sedatives, paralytics, vasopressors, inotropes, broad spectrum antibiotics, and bronchodilators. The full list of category A medications are marked with an asterisk in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Operationalizing this plan is ongoing since the implications of space, initial overstock cost, and possible wastage all provide challenges. Given that the overstock will simply be extra supply on hand moved through the normal rotation of medication use in hospital, wastage and additional cost impacts will be minimal.

Disaster binder and workflow

Disaster binders were created so procedures can be operationalized under duress, possibly by people who are unfamiliar with the pharmacy purchasing procedures. The first binder provides an overview of the ordering process, followed by vendor and staff contact lists, drug order forms, and a drug catalogue. The second binder contains reference resources including contact numbers and locations for the EOC, phonetic alphabet guide, Island Health Authority’s Pharmacy Disaster Policy and Procedure, Pharmaceutical Vendor Business Continuity plans, and an inter-authority agreement.

An outline of the workflow is shown in Figure 1. When a state of disaster is declared, the EOC determines the need to order an emergency supply of medications for each Island Health hospital location. The most senior South Island Pharmacy Leader in the EOC communicates this decision and coordinates pharmacy operations for Island Health as a whole. The Pharmacy Leader works with the EOC Logistics Leader to gather information including: the number of anticipated disaster patients for all 9 acute care hospitals (including rural sites supported by these acute care hospitals), the operational status of these sites (e.g., accessibility of current medication supplies), requirement for alternate delivery locations, and operational status of transportation and communications from areas that are shipping medication supplies. The EOC determines secure locations to store ordered drug supplies. The senior Pharmacy Leader in the EOC delegates either the Pharmacy Purchasing Coordinator, a Pharmacy Purchasing staff member, or an alternate pharmacy staff member to initiate the medication purchase orders, using additional staff as needed, for each site using the information provided by the EOC.

Figure 1. Emergency/Disaster pharmacy drug ordering flowchart. * Communications of this process may be initiated by anyone; however the medication purchase order must be approved as shown.

If all communications are functioning appropriately, the purchasing office will use standard purchasing procedures to initiate the purchase order using near normal processes. The vendor is then notified that the order placed requires immediate prioritization as part of the emergency disaster response.

Once the disaster purchase orders are submitted to the vendor (or activated by alternative means as described below), an update to the EOC Pharmacy Leader, geography EOCs, and each site pharmacy leader is provided to confirm that the medication purchase orders are initiated. Additional feedback provided to the EOC includes an estimated time of delivery, the expected means of delivery, and instructions for proper handling and storage of medications such as narcotics, anesthetic gases, and medications requiring refrigeration.

If the disaster impacts the capacity for normal purchasing procedures, copies of the pre-planned order sheets are available with both the vendor and a geographically distanced health authority (Interior Health) in the event further assistance is required. Should the disaster prevent Island Health from initiating the purchase orders via normal procedures, the vendor will activate and process the immediate purchase orders (already on file) based on the estimated number of disaster patients expected at each site. This information may be relayed to the vendor through the EOC or via Interior Health. This disaster preparedness plan has been confirmed with the vendor.

At Island Health, there is an inter-authority partnership with Interior Health to initiate the medication purchase orders if Island Health is unable to complete the task. Interior Health is a publicly funded health authority which provides healthcare services across the Okanagan, Kootenay, Thompson, Cariboo, and Shuswap regions of British Columbia. This partnership was formed based on the use of similar purchasing processes in each region and the low likelihood that a major local disaster event will significantly affect both health authority populations at a given time. This partnership involves no cash exchange and requires sharing disaster binders and contact information in the event of a disaster.

Basic communication may become inoperable in the event of a disaster; therefore, satellite phone capabilities are required, and information must be updated when vendor or administrative contact names change.

Immediate purchase orders

To provide an efficient and simplified ordering process, the disaster purchase orders are created for 1 vendor only, even if some products are usually sourced from other vendors at a lower cost.

There are 3 order forms: controlled, non-controlled part 1, and non-controlled part 2 (see Tables 2, 3, and 4). Given the large number of medications on our disaster order list, these separate lists were created to improve efficiency and to prioritize the most critical medications when sending purchase orders to the venders while under the duress of an acute disaster. The medications from the controlled and non-controlled part 1 lists will be ordered for each site as soon as possible, and the drugs from the non-narcotic part 2 form will be ordered as time permits or in parallel with another purchaser on site if available. However, it is expected that all drugs from the 3 order forms will be ordered within 24 hours of a disaster.

The order quantities for each medication on the purchase order forms are predetermined to facilitate a quick and efficient ordering process based on the anticipated number of disaster patients per site (provided by the EOC). While imperfect, these order quantities were based on current drug usage patterns per patient (defined by the 3-year purchase reports as described above), a subjective estimate of the increased usage in the event of a disaster, and the likelihood of increased outpatient medication dispensing. The order quantities were then rounded to appropriate orderable quantities on the order sheets for options of 200, 500, 1000, or 1500 disaster patients. If a hospital’s current medication supply is not accessible due to the disaster, the purchase order may be increased by an additional 200-1000-patient supply (to be determined at the time of the disaster).

Limitations

Different geographies may have different medication needs based on different disaster risks. A large earthquake and tsunami currently pose 1 of the greatest risks to Vancouver Island, but this is not the case for many other geographies. Some disasters may not require many medications in the response, so this described strategy may not be appropriate for all types of disasters.

This disaster plan is for medications only and must be coordinated with strategies for other supplies (e.g., syringes, needles, intravenous tubing). Medications not available through normal vendor procedures are ordered from specialty vendors or general stores. It is expected that most hospital pharmacy departments have an additional disaster plan for staffing. Initiating the procedures outlined in this document should be considered when creating a staffing plan.

It is unclear if having 1 person complete the purchase orders for all sites in a health authority is more advantageous than having staff from each site follow the disaster binder procedures. This may be disaster-dependent, and the outlined strategy provides the structure for either option at the EOC’s discretion. The challenges with transportation and delivery of supplies during a disaster is typically handled by the EOC and outside the scope of this review.

Large scale disasters can impact medication supply chains, and there is no guarantee that an immediate drug order will be fulfilled and delivered efficiently during a disaster event. Therefore, inventory mitigation strategies were included as a surplus for target medications. However, physical space and avoiding drug wastage and budgetary losses are significant considerations.

While selecting the medications for use in a disaster, multiple drug strengths are ordered to avoid issues with backorders if a specific strength was not available at the time. However, choosing a single strength of a specific drug would allow for a shorter order list and quicker completion of the purchase order. Furthermore, the threshold of requiring 200 disaster patients to initiate a medication purchase order was arbitrarily chosen and there is no data to support this. It simply reflects a reasonable estimate of current surge capacity within Island Health. Previous disasters provided insight on the possible surge demand (including possible ED presentation and admission rates), but this data may not be generalizable to other geographies and disaster types. Reference Klitzman and Freudenberg7,Reference Pang, Lim, Chua and Seet8,Reference Equipment23,Reference Higgins, Wainright, Lu and Carrico28–Reference Yen, Chiu and Schwartz31

This strategy is based on numerous subjective assumptions. The EOC must provide an early estimate of the number of disaster patients expected to present to health care sites, which may be inaccurate at the onset of the disaster. Clinical judgment was used to create the list of medications for category A and B (i.e., overstocking and the immediate medication purchase orders). While a reasonable process for stakeholder input was included, broader input may further strengthen the final list of medications identified in this disaster plan. Analytics used to capture the number of patients seen in Island Health over the 3-year medication purchase order history (i.e., to create an estimate of normal drug usage patterns per patient) may not accurately represent medication usage for patients seen during a disaster event. Additionally, estimating the deviations from these calculated medication usage patterns during a disaster event is not evidence-based. Lastly, this strategy does not account for previous reports that medications could be hoarded out of panic by individuals in the healthcare industry. Reference Tsai, Lurie and Sehgal32,Reference Sterman and Dogan33

The authors acknowledge that such compromises lead to an imperfect disaster plan, but this may hopefully serve as a foundation for further iterations and discussions in disaster preparedness literature.

Conclusion

While individualization of health authority disaster plans for medication supplies is important, this Island Health Authority disaster preparedness strategy for the procurement and minimum stock levels of high priority medications may provide a template for further disaster plan improvements.

Acknowledgements

John Bartle-Clar and Heather L Smith: pharmacy purchasing leadership. Island Health professionals who contributed stakeholder feedback include Jolanta Piszczek, Erica Otto, and Celia Culley who served on the final panel. Thanks also to David Bemrose and Deborah Exelby for their contributions.

Author contributions

DC assisted with the formatting of the disaster plan documents. RW led the creation and subsequent updates of the disaster plan. DC and RW both conducted literature reviews and wrote the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None