The reign of Francis I (r. 1515–47), king of France and patron of arts and letters, brought with it numerous changes and innovations, including the adoption of French as the language for all official records, the establishment of the Collège de France and the Royal Library, the creation of the five royal printers, including the Royal Printer of Music, and the overhauling of the musical court establishments. It was during this period that the Parisian printer Pierre Attaingnant introduced the single-impression method for music printing and became the first Royal Printer of Music in 1537. One of his most striking achievements as a music printer was a fourteen-volume series of motet books, published between 1534 and 1539.Footnote 1

Motet printing prior to the mid-1530s generally involved the printing of a series of books: Petrucci had produced two series, the letter series (Motetti A–C, followed by two numbered volumes) of 1502–7 and the Corona series of 1514–19; Antico continued the trend with his four-volume Motetti novi of 1520–1; and Moderne released three volumes of his Motteti del fiore series in 1532.Footnote 2 Attaingnant’s series departed from the standards established by these three printers in several respects: the number of volumes was increased dramatically; the overall organisation and design of the series was standardised; and it included extra-musical information on the title pages and inside the books, what we shall call rubrics.Footnote 3 In addition to the novelty of including such information in a book of motets, these rubrics have a significant bearing on the use and organisation of the series. While the choice of motets and rubrics is often general enough to have appealed to foreign markets, there are clear signs that the printer was preserving local traditions of liturgical use, including the use of Paris, in his series.Footnote 4

A consideration of the terminology of the rubrics and their use by Attaingnant also provides new insight into the perennial issue of the function of the motet in the sixteenth century, a genre that was favoured by Francis I and figured prominently in his private and public devotions. Indeed, the king’s singers composed a significant number of motets in Attaingnant’s series. The connections to the king and strong flavour of local traditions preserved in the series suggest a deliberate agenda on Attaingnant’s part, one which coincided with Francis I’s efforts to extend his political influence through patronage of the arts and letters, political alliances and religious campaigns.

THE MOTET SERIES

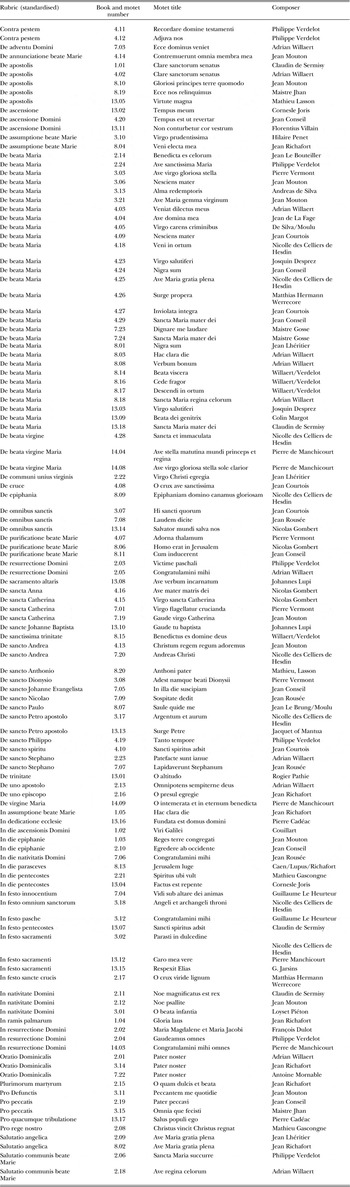

The series contains 281 motets by sixty named composers including Jean Mouton, Philippe Verdelot, Adrian Willaert, Pierre de Manchicourt, Mathieu Gascongne, Jean Richafort and Claudin de Sermisy.Footnote 5 Attaingnant released the first thirteen books of his series over the course of a single year, at a pace of roughly one book per month, with the fourteenth book appearing in 1539 after a four-year hiatus.Footnote 6 (See Table 1.)

Table 1 Title and printing date of the books in Attaingnant’s motet series

a The date included on the title page indicates that this book was printed at the end of March, after Easter, which fell on 28 March 1535.

The speedy and steady production pace of these books was unprecedented in Attaingnant’s workshop and the high degree of organisation that is evident in the assignment of rubrics to these books and motets indicates a lengthy period of preparation for this series. Indeed, there is documentary evidence suggesting that Attaingnant was planning his series at least three years before it went to press. In the 1531 royal privilege granted to Attaingnant, Francis I accorded him protection for music he had already printed, was printing and was planning to print, including future books of masses, motets and chansons.Footnote 7 These three groups coincide with the three large series that Attaingnant produced in the next several years, in exactly that order of production. The three years leading up to the release date of the first book of his motet series provided Attaingnant with ample time to design his series, considering special issues like the type of anthology, the ordering of the books and the assignment of rubrics to his motets.

The books in the series appear in two types of anthologies. Books 1–4, 8, 11 and 13 are the standard anthology type produced by Petrucci and Moderne: books containing motets by many composers on a variety of subjects or topics, what we shall call here ‘mixed anthologies’. Starting with the fifth book of the series, Attaingnant began to favour a different type of anthology, one which contained motets on a single topic or which set a single text-type.Footnote 8 These special anthologies, which we shall call ‘uniform anthologies’, were atypical for the era and permitted the printer to organise the motets in a highly systematic manner and also lend greater cohesion to the books and the series.Footnote 9 The uniform anthologies also gave Attaingnant a unique marketing opportunity: the printing of books for specific liturgical seasons. The seventh book of the series, which contains music for Advent and the Nativity, has a printing date of November, coinciding with the start of the Advent season; while the tenth book of the series, which contains music for Lent and Holy Week, appeared in February 1535 at the start of Lent.Footnote 10 Regardless of type, each book of the series advertised the titles of the motets on its title page in a detailed tabula, but the uniform anthologies also featured special rubrics that formed part of the book titles.

THE RUBRICS

Rubrics in liturgical books give specific directions for the performance of a liturgical item, or indicate the feast day and office at which the chant or text is to be performed. These rubrics function as directives: do this for this chant; sing this chant at this time. Liturgical rubrics range from longer instructions to shorter ‘headings’, but rubrics were also common in private devotional books, such as books of hours, where they had a descriptive function, indicating the subject of the text which followed or the type of text (e.g., ‘oratio’ for prayer). Similar rubrics are also found in graduals or ordinals.

In many printed books of hours changes in font or size, special characters or initials, or customary placement of the rubrics at certain places on the page were used to distinguish the rubrics from the rest of the text. The rubrics included in Attaingnant’s series generally fall under the descriptive heading type, which identifies the subject and/or feast of the motets. Many of the rubrics bear a resemblance to those found in books of hours, but can also be found in the commons sections of some liturgical books, notably antiphonals, breviaries and graduals.

There are two types of rubrics in Attaingnant’s series: those which appear as part of the titles of specific books and those which are assigned to individual motets. While the title rubric does not conform to the visual elements of rubrics as described above, it does function in the same manner as a descriptive rubric, identifying a potential occasion for which the motets could be sung or the type of text which is set. In one instance, it also provides performance directions to the singer.

Six of the fourteen books in the series contain rubrics in their titles. These books are all uniform anthologies with rubrics that pertain to the subject of the texts of the motets, or to the text-type of the motets contained in the books. Although Petrucci used this type of rubric in the title of his Motetti B edition in 1503,Footnote 11 Attaingnant’s title rubrics and anthologies are remarkably homogeneous, with rubrics which refer to a single text-type or season. Apart from allowing the printer to capitalise on the marketing potential of specific seasons, this also gave the books appeal as stand-alone volumes, though as we shall see, Attaingnant clearly expected and encouraged his market to purchase the entire series.

The first books in the series to contain title rubrics are books 5 and 6, which contain between them settings of the Magnificat on all eight tones. The rubrics on the title pages of books 5 and 6 identify the contents of the books as Magnificats, on the different Magnificat tones: book 5 contains settings on the first three tones; book 6 on the five remaining tones.Footnote 12 The pieces contained in these two books are incomplete settings of the text; most pieces set only half of the text of the Magnificat, requiring the addition during performance of either the odd-or even-numbered verses in chant.Footnote 13

Books 9 and 12 also contain settings of a single text genre. Book 9 contains psalm-text settings and book 12 contains motets ‘ad virginem christiparam salutationes’, salutations to the Virgin, Mother of Christ.Footnote 14 All of these rubrics are the short descriptive type: they simply tell us about the contents of the books and subjects of the motets. All three text-types in books 5, 6, 9 and 12 are also genres that were common in liturgical books, and the alternatim settings of the Magnificat would certainly indicate a liturgical context for the performance of these works. Indeed, the wording of the rubrics itself could also suggest a liturgical connection; the reference to the Magnificat tones could imply a liturgical use. But the rubric for book 9, ‘daviticos musicales psalmos’, presents a few problems when considered in relation to the contents of the book. The rubric implies that the contents of book 9 are polyphonic settings of psalms, which might reasonably lead the reader to expect complete settings of the psalms. Yet the motets of the ninth book do not all fulfil the promise implied by the rubric.

Book 9 contains eighteen motets, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Contents of book 9 with composer name, title of motet and psalm number * indicates a setting of extracts from the psalm, not the complete text.

Twelve of the motets are complete settings of psalms, but only three of them contain the Lesser Doxology. The remaining six motets set fragments of psalm texts. While they can function as stand-alone polyphonic works, they are not suitable for liturgical use in the manner of the Magnificat settings in books 5 and 6.Footnote 15 Attaingnant’s terminology is therefore somewhat misleading from a liturgical point of view. If, upon opening the book, the singer expects to find liturgically sound or complete ‘musical psalms of David’, they will surely be disappointed. On the other hand, the motets would be appropriate for devotional use and in circumstances where reading or singing the complete psalm text was not required. The fact that all but one (Sermisy’s Deus in adjutorium) of these eighteen psalms are part of the core sections of contemporary books of hours (referring here to the Hours of the Virgin and Hours of the Cross, and not to the ancillary psalters that are occasionally appended to the book of hours) could suggest a devotional use for these motets, either in the private home or by confraternities.Footnote 16

The wording of the title rubric for book 12, ‘ad virginem christiparam salutationes’, corresponds effectively to the contents of the book, a collection of ‘musical salutations to the Christ-bearing Virgin’. The phrase is clearly meant to evoke the idea of the Salve or Salut services that were conventionally celebrated after Compline and the ‘salutations’ or Salve included in books of hours after the Compline texts.Footnote 17 But even here, the wording of the rubric and the contents are not as straightforward as they appear. Book 12 contains seventeen settings of the great Marian antiphons Ave Regina caelorum, Regina caeli and Salve Regina. (See Table 3.) All settings feature the chant in some form or other, making them suitable for a Salve service, and the rubric and the contents of the book suggest a specific local liturgical or devotional use, a hint at the context in which they were printed.

Table 3 Contents of book 12 with composer name and title of motet

In the early sixteenth century, the Salve in many liturgical and devotional uses, including the use of Rome, featured one of the four great Marian antiphons. The choice of which antiphon to use depended on the time of year. Typically, Alma Redemptoris Mater was sung during Advent, Ave Regina caelorum was sung from Purification to Easter, Regina caeli was sung from Easter until Trinity and Salve Regina was sung from Trinity until Advent. A slightly different function for these antiphons is preserved in books of hours prior to 1550, in which the four great Marian antiphons were included at various canonical hours: Regina caeli and Salve Regina appear after the texts for Compline, but also appeared at various other hours including Lauds, along with Ave Regina caelorum and Alma Redemptoris Mater.

Noticeably absent from Attaingnant’s book 12 are settings of Alma Redemptoris Mater, which points to a specifically Parisian use. In 1535, the year book 12 was printed by Attaingnant, only three of the great Marian antiphons were part of the liturgy of the Office in Paris. At Notre-Dame de Paris, Ave Regina caelorum and Salve Regina were sung as part of the Salve service after Compline every Saturday and Sunday respectively, while Regina caeli was sung daily after Lauds.Footnote 18 Ave Regina caelorum was also sung daily for the procession at Terce and High Mass.Footnote 19 Alma Redemptoris Mater was not accorded the same status as these three antiphons, nor did it have a fixed place within the liturgy of Paris.Footnote 20 Similarly, in the use of the king’s chapel, which was largely based on the use of Paris, only the three ‘Regina’ antiphons were sung on a regular basis.Footnote 21 The situation was similar in books of hours for the use of Paris and the book of hours in general, which incorporated the three ‘Regina’ antiphons much more frequently throughout the hours than the contemporary liturgy. The fact that Attaingnant included settings of Alma Redemptoris Mater in two earlier books of his series seems to suggest that they were deliberately excluded from book 12, perhaps in a effort to preserve (or promote) the use of Paris and to appeal to the Parisian market. Book 12 thus reflects local Parisian liturgical and devotional practices, and more generally has strong links with books of hours, links that would no doubt have been recognised by the book of hours market. The term ‘salutationes’, however, neither forecloses use beyond Paris, nor does Attaingnant suggest specific days on which the motets should be sung.

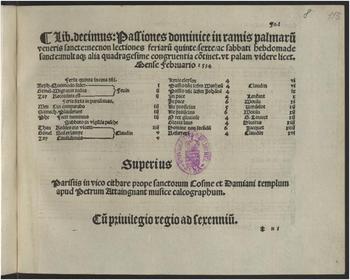

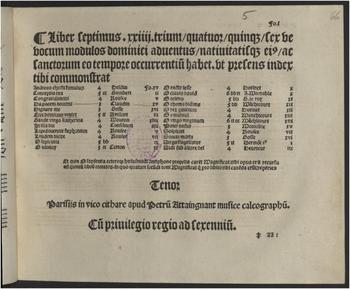

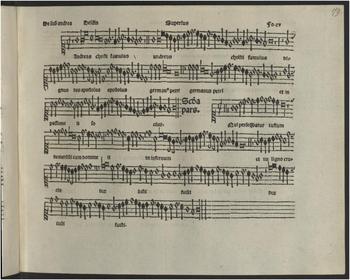

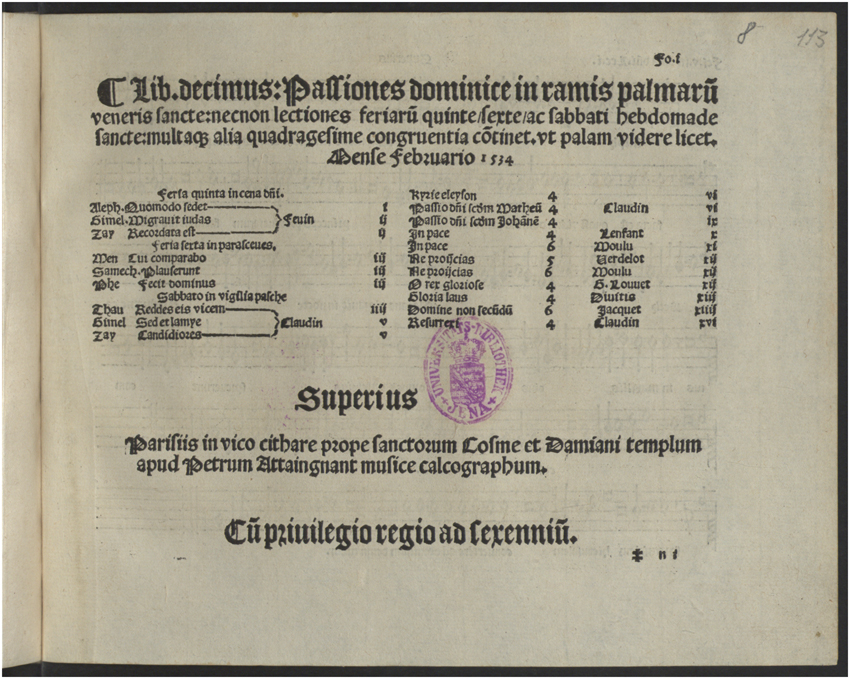

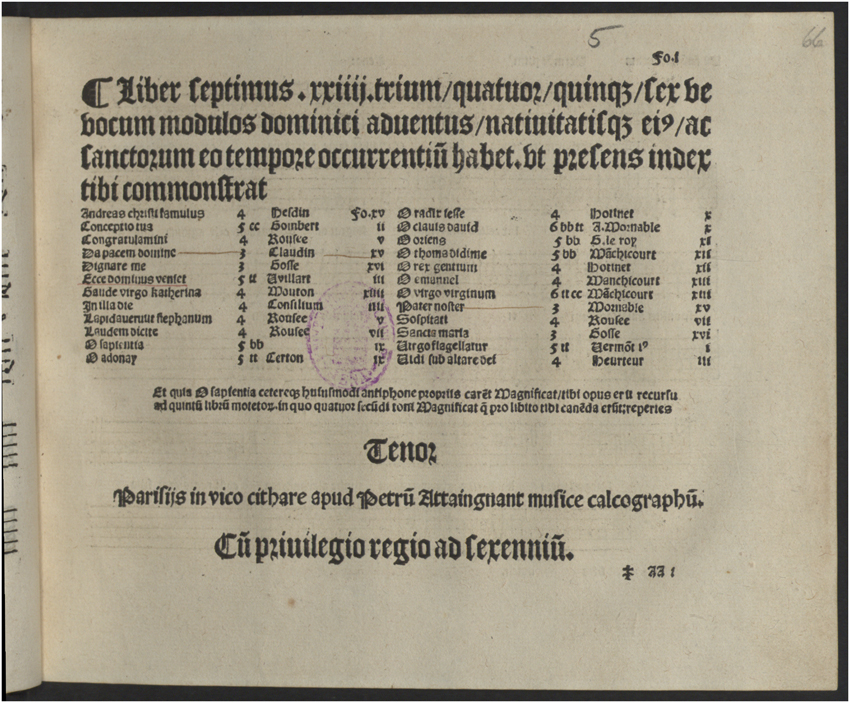

Two other instances of local use are reflected in the title rubrics and contents of books 7 and 10; however, the title rubrics of these two books differ from those previously discussed. The title rubrics used by Attaingnant in books 5, 6, 9 and 12 all imply a single text-type and/or subject for the motets contained in the books: all are Magnificats, all are psalms or all are salutations to the Virgin. For books 7 and 10 the title rubrics refer to motets on more than one subject. The rubric for book 10 indicates that the book contains Lamentations and Passion settings for Holy Week and Easter, as well as other motets suitable for Lent. A study of the text sources for these motets found that not only did all the texts have a tradition of use for Lent and Holy Week, Attaingnant actually ordered the contents within the book according to their function: lessons (Lamentations) are grouped according to the day on which they would be sung starting with Maundy Thursday (‘Feria quinta in cena domini’) and ending with Holy Saturday. The Kyrie divides the Lamentations from the Passions, which are also presented in calendar order: the Passion of Matthew (for Palm Sunday) followed by the Passion of John (for Good Friday). The remaining settings are generally ordered according to the use of Paris, starting with In pace for the Second Sunday of Lent and concluding with Resurrexi et adhuc, sung at the opening of Mass on Easter Sunday.Footnote 22 (See Figure 1.) Attaingnant’s attention to local liturgy and devotional traditions is also evident in book 7 (see Figure 2.) Attaingnant’s rubric states that the book contains music for Advent and the Nativity and also motets for the individual saints’ feasts which occur at this time. Rubrics inside the book more precisely identify some of the motets whose subjects were not immediately evident, and distinguish those for Advent and the Nativity from those for individual saints’ feasts.

Figure 1 Title page of the superius partbook of Attaingnant’s tenth book of motets with title rubric indicating that the motets pertain to the Holy Week and Easter season (Jena, Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, 4 Mus.2a (5), Bl. 236)

Figure 2 Title page of the tenor partbook of Attaingnant’s seventh book of motets with title rubric indicating that the motets pertain to the Advent and Nativity season (Jena, Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, 4 Mus.2c(5), Bl. 140)

The title page of book 7 outlines the contents of the book. At the core are the nine ‘O’ antiphon settings: O Sapientia, O Adonay, O Radix Jesse, O Clavis David, O Oriens, O Thoma Didime, O Rex Gentium, O Emmanuel and O Virgo Virginum. These ‘O’ antiphons were sung with the Magnificat as part of the Vespers liturgy during Advent at Notre-Dame de Paris, a tradition dating back to the eighth century.Footnote 23 They were sung on the nine days leading up to Christmas and Attaingnant preserved the local liturgical and devotional order when he printed them in his book.Footnote 24 Evidently, the printer felt that the subject and use of these motets was sufficiently clear from the title rubric and that they needed no other identification. The remaining motets were apparently not as universally (or locally) familiar, and we see signs of Attaingnant’s concern that the user of the book be able to quickly identify the subject of these motets and their place within the Advent season using the accompanying rubrics. Jean Rousée’s Sospitati dedit aegros, for example, has no hint of its subject in the title. The subject and use would no doubt have been clear for those who sang the liturgy every day, but without the rubric ‘De Sancto Nicolao’ identifying one of the saints celebrated during Advent (6 December), the subject and relevance of the motet for the season is ambiguous. This suggests that Attaingnant was catering at least in part to people who were not members of professional choirs or employed at one of the many churches and cathedrals in Paris. Indeed, the texts for these ‘saints’ motets were also common in books of hours.Footnote 25 The presence of motets to saints with a strong local connection, like St Catherine, St Andrew and St Denis, is an additional link to the liturgical and devotional traditions of Paris, and more generally France. However, these saints were also widely celebrated, thus ensuring a degree of versatility for the book, while still promoting the local use.

This clearly illustrates an intention on Attaingnant’s part to respect or even promote a specific tradition and to order the pieces according to the liturgical calendar.Footnote 26 This is perhaps not surprising when we consider the context in which the books were printed and sold, for in addition to printing large quantities of polyphonic music, Attaingnant also produced liturgical books and sold books of hours in his Parisian bookstore.Footnote 27 He would certainly have been aware of the potential to appeal to these two groups with user-friendly books of polyphony organised according to local liturgical and devotional use.

The ‘O’ antiphon settings have another significance that speaks to the large scope of the series and Attaingnant’s intention that the books in his series be used together. On the title page of book 7, after the rubric stating the subject of the motets, Attaingnant added this note: ‘And since O Sapientia and the other antiphons of this kind lack their own Magnificat, you will need to go back to the fifth book of motets, in which you will find four second-tone Magnificats which can be sung at your pleasure.’ Attaingnant informs his reader/singer that the ‘O’ motets in book 7, which are all in the second mode, should or could be sung with Magnificats, and also refers them back to the fifth book in this series in order to find the appropriate Magnificat settings.Footnote 28 This is significant on two fronts, one which pertains to the use of the books and the other (which I shall address below) which pertains to the function of the motet.

Attaingnant’s note implies a degree of cohesion that was completely unprecedented in motet series printed prior to these books. He apparently expected his market to buy the entire series and to use the different books in conjunction with one another. Presumably this decision was geared towards those who might sing the Magnificats together with the antiphons, such as choirs at local churches and cathedrals. However, I would argue that a private devotional use can also be inferred from the rubric and the contents of the book. By explaining that the reader could find the appropriate Magnificats in book 5, Attaingnant was catering to the non-professional, the amateur singer, who would use this book for private observances and devotions and would not necessarily have a wealth of Magnificats at home from which to choose. Because the Magnificats lack alternate verses, the individual who purchased book 5 would still need an additional devotional book that could provide the missing text at the very least, assuming an extra-liturgical performance. The book of hours, which featured the complete Magnificat and occasionally the O antiphons, could have been used to fill in the missing texts, a fact which could point to a private, devotional use for these books. The possibilities of cross-marketing would surely have appealed to a businessman like Attaingnant, who in fact sold books of hours and liturgical books in his own bookshop along with books of polyphony.Footnote 29

The title rubrics in Attaingnant’s series reflect the overall contents of the books, identifying the subjects or text genres of the motets, suggesting appropriate occasions for their performance. They also contribute to the cohesiveness of the series. These fourteen books were not simply printed in succession at random as new motets were collected, but were organised according to the texts which they set and were meant to be used together. If we turn our attention to the contents of those books without title rubrics, we find an equal attention to the subject of the pieces.

INDIVIDUAL MOTET RUBRICS: BOOKS ONE TO FOUR, SEVEN, EIGHT, THIRTEEN AND FOURTEEN

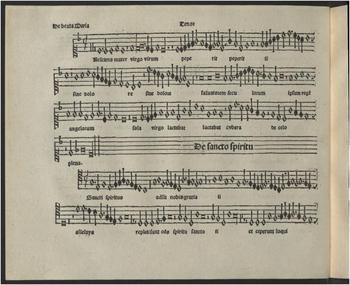

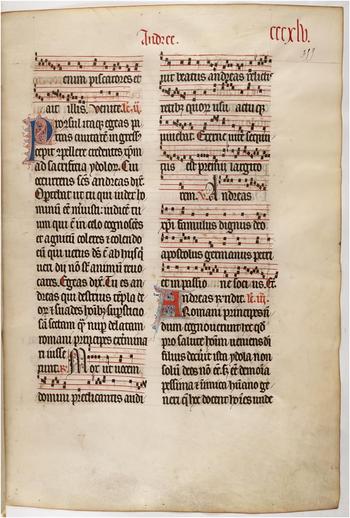

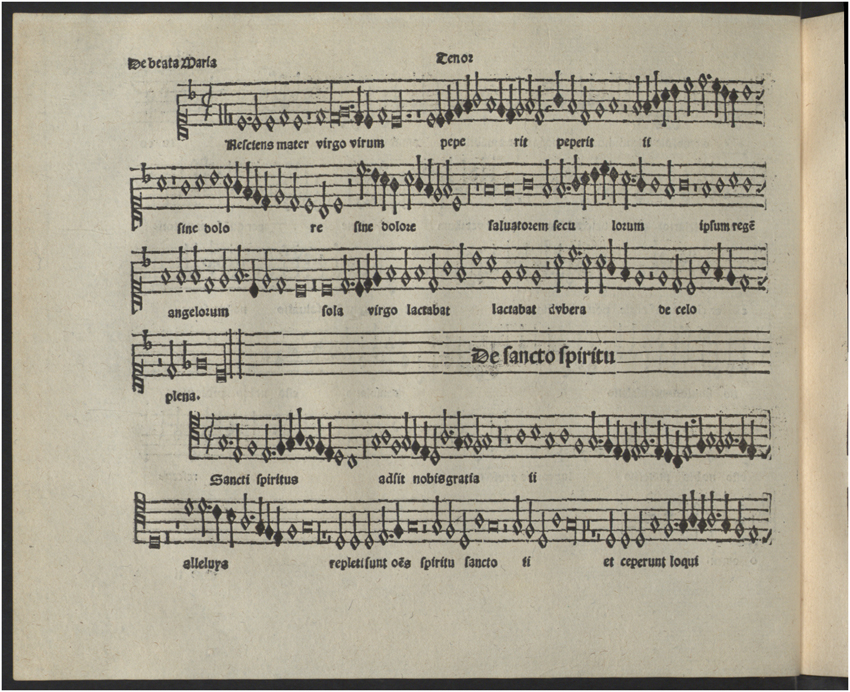

The ‘individual’ rubrics in the series appear principally in mixed anthologies. They are typically placed at the top of the page in the left-hand corner of the running head, or if a piece begins part-way down the page, the rubric is found within the stave that precedes the new motet, in a larger font to distinguish it from the rest of the text. (See Figure 3.) Of the 281 motets in Attaingnant’s series, 118 appear with an ‘individual’ rubric, totalling more than 40 per cent of the repertory, not including those in uniform anthologies without individual rubrics, such as the contents of books 5, 6, 9 and 12, which could conceivably have the rubric ‘Magnificat’, ‘daviticos psalmos’ or ‘ad virginem christiparam salutationes’. If we were to take into consideration all motets which appear with an individual or title rubric, the total would be 230 motets, more than 80 per cent of motets in the series.

Figure 3 Folio 6v from book 4 of Attaingnant’s motet series (tenor partbook) with rubrics at the top of the page (‘De beata Maria) and within the stave (‘De sancto spiritu’) (Jena, Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, 4 Mus.2c(5). Bl. 119)

The rubrics in Attaingnant’s motet series which appear at the start of individual motets resemble those rubrics more commonly associated with the Commons sections of graduals and processionals and books of hours. They indicate the subject, feast or occasion on which the motets could be sung. They range from rubrics for unspecified liturgical occasions to those which refer to a particular feast day. Most rubrics fall under three broad categories: Marian rubrics, rubrics related to feasts in the sanctoral cycle and rubrics related to feasts in the temporal cycle. A small group of rubrics, referred to here as ‘miscellaneous rubrics’, do not belong to any of these categories.

Marian rubrics refer either to the Virgin Mary or specific feasts associated with her and are by far the most common, accounting for forty-four of the 118 motets with an individual rubric. These Marian rubrics also represent the different degrees of detail given by Attaingnant. More than half of the Marian rubrics (twenty-nine of forty-four) are simply ‘De beata Maria’, indicating that the motet is appropriate for any Marian feast throughout the year, or for any occasion on which the singer would like to pray to or celebrate Mary. These rubrics are commonly found in graduals and other liturgical books in sections of general Marian material. Other rubrics are more specific, like the rubric ‘De assumptione beatae Mariae’ for the motet Virgo prudentissima, which indicates that the piece could be sung for the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, which fell on 15 August.Footnote 30

The miscellaneous rubrics category includes a broad range of subjects: ‘Pro rege nostro’, ‘Contra pestem’, ‘Pro peccatis’, as well as those relating to the Holy Spirit or the Blessed Sacrament (‘De sancto Spiritu’ and ‘In festo Sacramenti’); three appearances of the rubric ‘Oratio Dominicalis’; and one rubric stating that the piece is appropriate ‘Pro quacumque tribulatione’.Footnote 31

The rubric ‘for the king’ is found in both liturgical books and books of hours (especially French books of hours) and has a special place in the series. It is assigned to the motet Christus vincit Christus regnat by Mathieu Gascongne and is the only direct reference to the king included in the rubrics.Footnote 32 The text is taken in part from the Laudes Regiae, a text commonly used for the coronation of kings, and includes a direct reference to Francis I, an important local connection.Footnote 33

The rubric ‘Contra pestem’ (against the plague) appears twice in book 4 and is found in both books of hours and liturgical books. It reflects a specific, perhaps local, use for the motets, or at least the texts of the motets. Recordare domine, the first motet with this rubric, sets an Introit text that was part of the Missa vitanda mortalitate, a votive service that was used specifically in response to threats from the plague.Footnote 34 The text of the second ‘plague’ motet Adjuva nos was also connected to plague liturgies, as part of the gradual for the Missa vitanda mortalitate.Footnote 35 Both motets were composed by Philippe Verdelot and usually travel as a single motet.Footnote 36 The motets also feature a foreign cantus firmus taken from the solemn motet Parce domine by Jacob Obrecht, who famously died of the plague in 1505.

The use of the rubric ‘Contra pestem’ may thus be seen as a reflection of the liturgical uses for the two texts (both associated with votive services against the plague but apparently never in the same source) and the history of the motets and cantus firmus, which would have been less than a decade old when Attaingnant printed them in his series. Dividing the motet into two separate pieces allowed Attaingnant to reflect the liturgical uses of the texts and provided not one but two pieces that could be sung against the plague. Attaingnant’s rubric indeed does not restrict the use of the two motets to any one situation. It does not employ the phrase ‘Missa vitanda mortalitate’ or refer to a specific liturgical service; ‘against the plague’ simply means ‘this motet is suitable for singing against the plague’, for whomever the buyer might happen to be. It allows for use of these motets during votive services, but also in other events organised to ward off the plague, such as processions or private confraternal devotions, or even private familial gatherings.

As was the case in the books with title rubrics, all of the rubrics assigned to individual motets correspond either to the subject of the motet text, or to the traditional, liturgical or devotional use of the text. In many cases, motets with the same rubric within a book are grouped together, such as the two plague motets in book 4, or groups of Marian motets in numerous books of the series.Footnote 37 In one instance, Attaingnant ordered the contents of a single book according to the categories of the rubrics. The subjects and indeed some of the texts of the motets in book 2 are common throughout the series, but what sets this book apart is the deliberate grouping of motets according to rubric, resulting in distinct sections. Book 2 contains twenty-four motets on a variety of subjects ranging from Marian texts to settings of Paschal texts, and even sacred Latin poetry. The contents are divided into two parts: the first with rubrics predominantly from the temporal cycle; the second with a large number of rubrics that coincide with the sanctoral cycle. (See Table 4.) The two sections are further divided according to season or subject, with each grouping set off by a Marian motet. Reflecting the general treatment of Marian texts in the series, the rubrics here vary depending on the use of the text that Attaingnant wanted to promote. While the printer was not always consistent in his use of rubrics for a given text, we see that Ave Regina caelorum is here identified with the term ‘salutatio’, the same term used for the motets on the same text printed in book 12, though here the word ‘communis’ indicates that these motets are for general Marian use.Footnote 38

Table 4 Contents of book 2 with motet title, rubric provided in the print and the liturgical context Large sections are separated by a double line, internal sections by a single line.

Book 2 succinctly reflects Attaingnant’s organisational practices and overall use of rubrics, with general and specific rubrics for individual motets. Rubrics are assigned to motets with texts that had a traditional, liturgical or devotional use and for composite texts, but not usually for contemporary texts or those of a secular nature. In fact, an underlying trend in the series seems to be to omit rubrics for motets whose subject is God.Footnote 39 For example, the text of Richafort’s Christe totius dominator is a Latin poem by the Croatian poet Juraj Šižgorić and was printed as part of a collection of Latin poems on a variety of subjects.Footnote 40 In this instance, Attaingnant respected the non-liturgical nature of the text and did not assign it a rubric.Footnote 41 Interestingly, Attaingnant does use rubrics, here and elsewhere in the series, for motets whose texts are compilations of two or more texts. In book 2 alone he assigned rubrics to nine motets with composite texts, which would therefore have been unsuitable for use within the liturgy, but could be used in other contexts, such as processions, votive or devotional services, or even corporate or private devotions.Footnote 42 This leads us to a consideration of the use or function of these motets and the importance of the rubrics for our understanding of how Attaingnant viewed this repertory.

The rubrics could evidently serve as a guide for performance, telling the singer when he or she might sing these motets. They were also no doubt useful as a more general reference tool: a means of identifying the subject of the piece without having to read through the Latin text. For modern scholars, they tell us about the relevance of the motet for personal prayer for specific issues; we can see that these motets had a place in praying to a patron saint, as suggested by the rubric ‘De sancta Katherina’, or praying against the plague because of rubrics like ‘Contra pestem’. This suggests a private function for the motets and series, as well as a possible liturgical or paraliturgical function for the motets, or the use of these motets for votive services or special devotions. But to what extent was Attaingnant indicating or promoting a liturgical function for these motets, or reflecting a court devotional practice? A liturgical function could be implied in the instruction to sing book 7 antiphons with the Magnificat in the rubric on the title page and in the inclusion of ‘incomplete’ Passion and Lamentation settings in book 10. Indeed, John Brobeck has argued that the style of these pieces, of the Magnificat and ‘O’ antiphon settings, is not what we currently consider a motet style and that they were more in line with serviceable music: that they were ‘liturgical motets’.Footnote 43 But these pieces account for only a fraction of the motets in the series, and while Attaingnant may certainly have thought of them as appropriate in a liturgical context, that this was the principle function of the series as a whole seems unlikely.

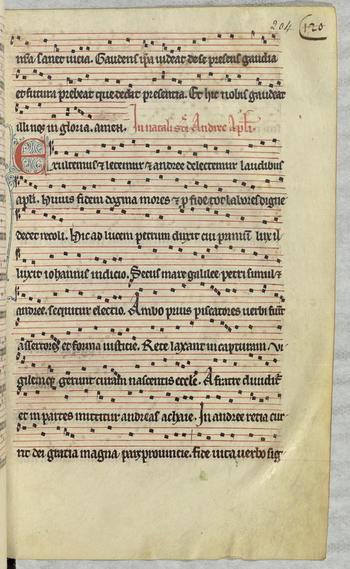

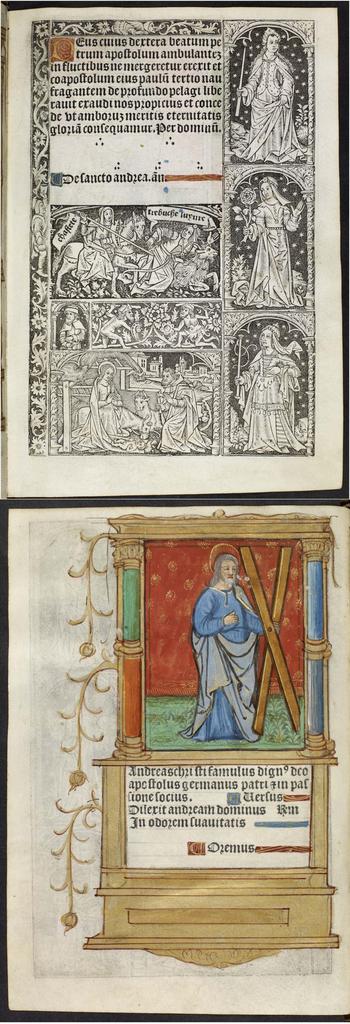

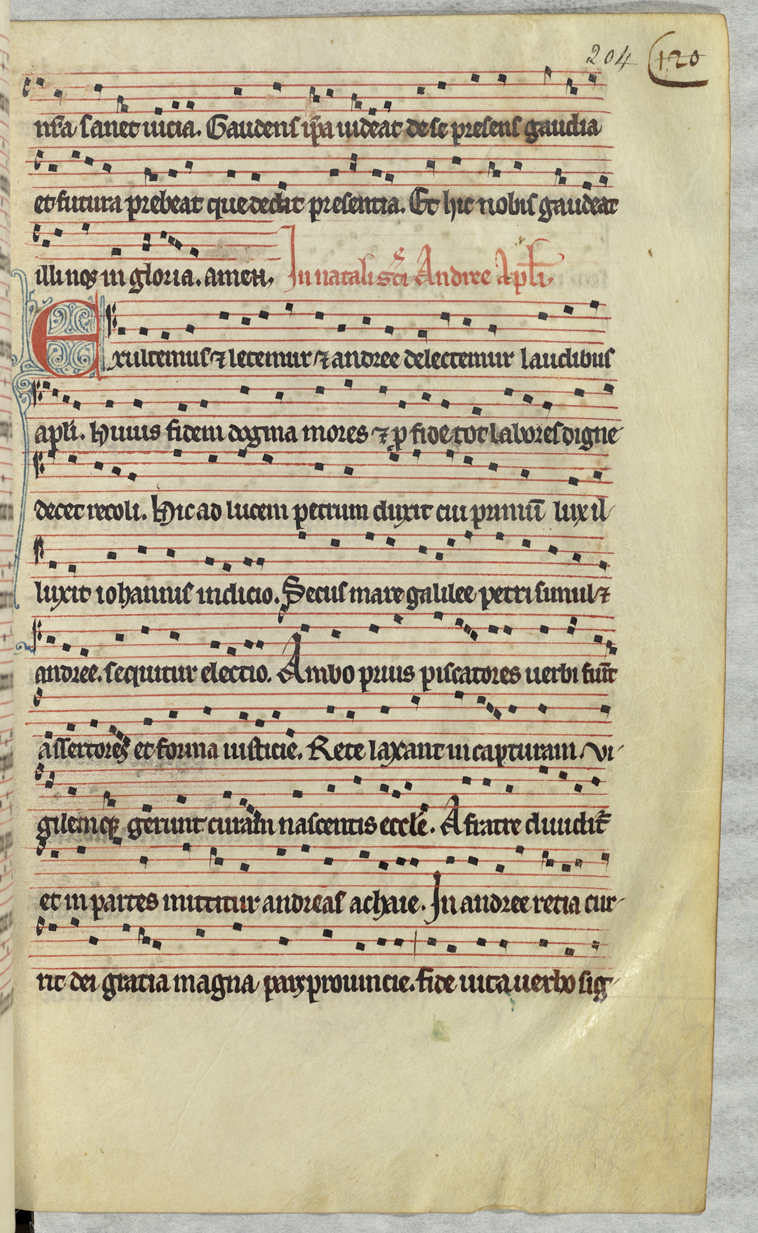

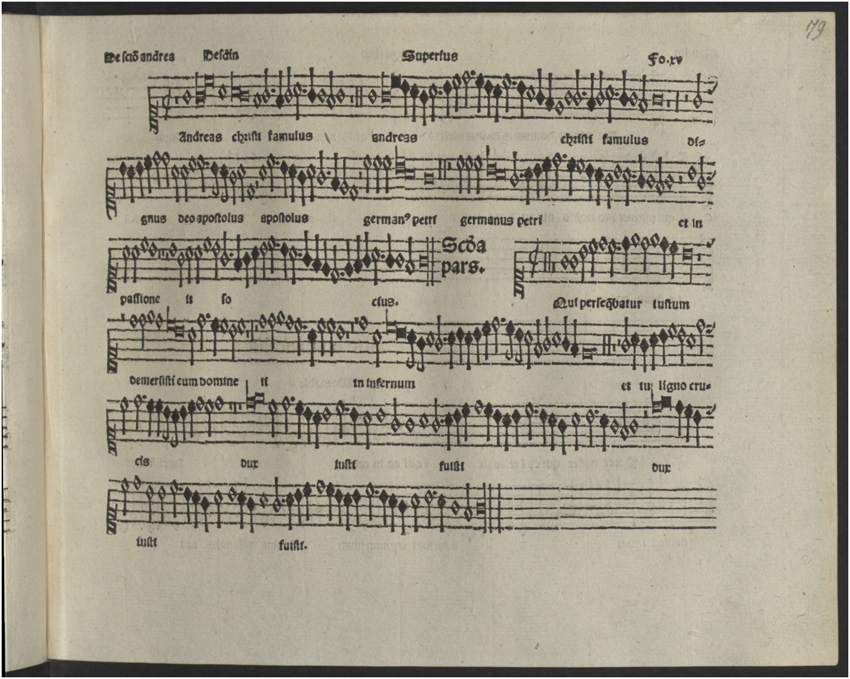

The inclusion of motets to individual saints and to Mary in book 7 suggests a more personalised, devotional approach. We do in fact find that the texts of some of these ‘liturgical’ motets, as well as the ‘O’ antiphons and Magnificats, are quite common in books of hours, and some of the motet texts in book 7 survive only in books of hours of the time.Footnote 44 They would no doubt also have been suitable for use at stational liturgies or votive services in honour of the Virgin. The rubrics themselves support a non-liturgical use, or rather allow for multiple uses: those that exist in liturgical books are also usually present in devotional books or general sections of liturgical books, which often feature material for votive or special services. These rubrics are descriptive and thus fall equally in line with devotional books and with the miscellaneous sections of graduals and processionals (this obviously includes the twenty-nine ‘De beata Maria’ rubrics).Footnote 45 From a visual perspective, the rubrics in Attaingnant’s series are often a closer match to those in books of hours than in liturgical books. Figures 4, 5 and 6 are from two liturgical books and a book of hours with rubrics for St Andrew. Comparing these to Figure 7 we can see that the book of hours rubric is a closer match for the Attaingnant rubric, both in the placement of the rubric away from the text and in the wording.

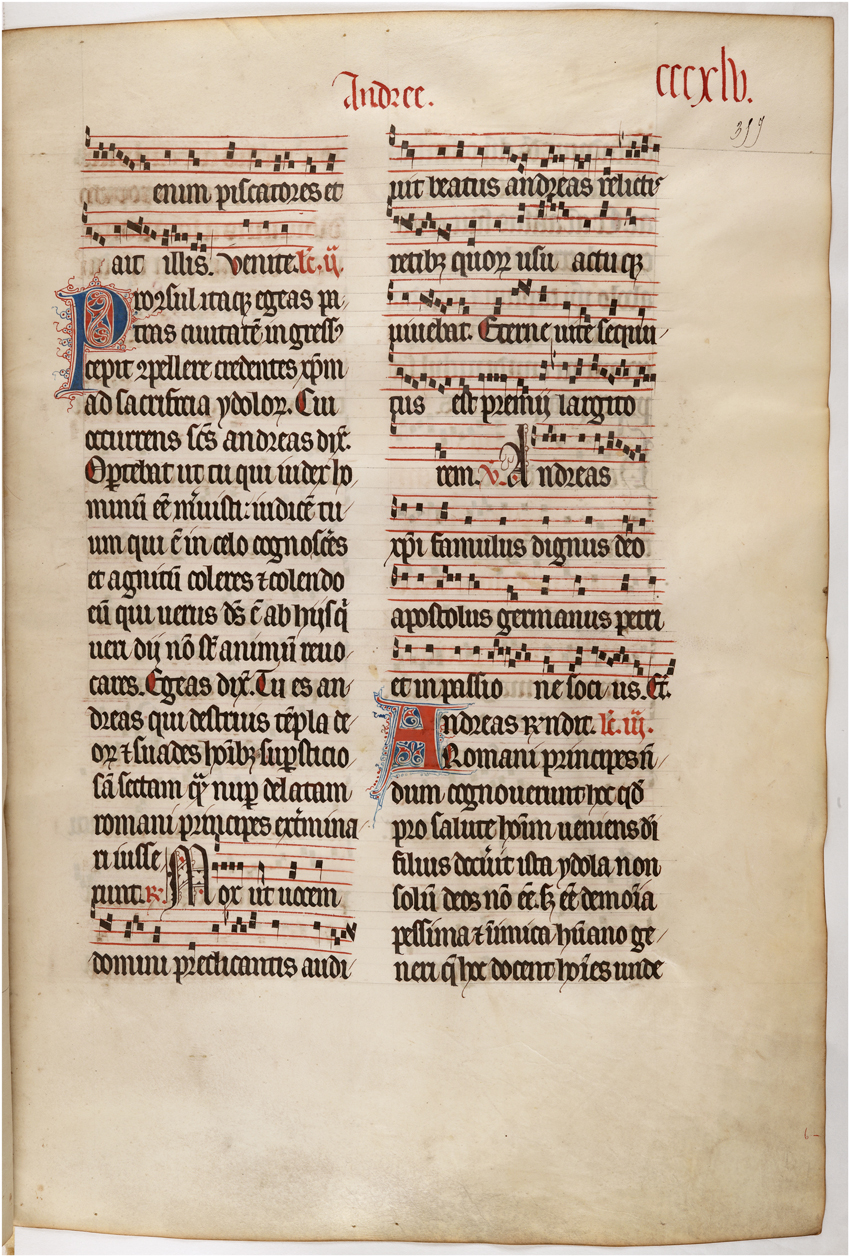

Figure 4 Breviary for use of Paris with rubric ‘Andree’ for St Andrew in red at the top of the page (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Lat. 15181, fol. 357r)

Figure 5 Parisian gradual with rubric for St Andrew (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Lat. 14452, fol. 204r)

Figure 6 Manuscript-print hybrid book of hours with rubric for St Andrew. A. Vérard, Hore beate virginis Marie ad usum Sarum (c. 1505). Rubric for St Andrew ‘De sancto andrea. an.’ (Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, CMB Pergament 19 4o, fol. 44r–v)

Figure 7 Rubric for St Andrew from book 7 of Attaingnant’s motet series (superius partbook): ‘De sancto andrea’ (top left-hand corner) (Jena, Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, 4 Mus.2a (5), Bl. 168)

That the Attaingnant rubrics reflected a local tradition for these motets (or their texts) is clear in the contents of book 12 and the choice of which ‘O’ antiphons were printed in book 7. Nevertheless, the use which Attaingnant assigned to these motets was not universally recognised, as is evident in the marginalia added to some motets by an owner of the series. The copy held at the Jena Thüringer- und Landesbibliothek includes fifty-one additional rubrics written in a cursive hand in the running heads and margins of the superius partbooks of books 1–8.Footnote 46 In some cases, the owner filled in the rubric indicated in other partbooks, for example he added the rubric ‘De S petro ap(os)to(lo)’ to the motet Argentum et aurem by Hesdin, the same rubric Attaingnant included in the tenor partbook (fol. xvv). He also assigned rubrics to motets which Attaingnant left undesignated, including sixteen additions to book 1, which contains only five printed rubrics (motets 1–5). The owner also filled in a rubric for Richafort’s motet Christe totius dominator from book 2, despite the extra-liturgical nature of the text. ‘De Christo’ here might refer to a tradition of singing the motet for celebrations or devotions to Christ. In addition to filling in the blanks, the owner also added a number of rubrics in order to more precisely identify the subject of some motets, and in a few cases actually contradicted Attaingnant’s suggested subject or use.

In two instances the owner of the Jena series made specific references to the French connections of the motets. For the rubric ‘Pro rege nostro’, which we saw in book 2 as assigned to the motet Christus vincit Christus regnat by Gascongne, the owner added the phrase ‘Oratio pro Francisco I rege Gallorum’. The motet text refers to Francis by name, but the owner here specified the Gallic connection. A similar addition appears on fol. vi of book 3: the owner added the phrase ‘De S Dyonisio Gallorum apostolo’ to Attaingnant’s rubric ‘De Sancto Dyonisio’, thereby identifying St Denis as a French apostle, a fact that would not have required explication for the Parisian or French market.Footnote 47

In ten instances, the later hand wrote in rubrics which contradict those printed by Attaingnant. He added an alternative rubric to six motets which Attaingnant described as ‘De beata Maria’. The rubric for Josquin’s Virgo salutiferi indicates that the motet is ‘Salutatio angelica’, referring to the use of the chant Ave Maria gratia plena as the cantus firmus of the motet, but still related to Attaingnant’s rubric. The owner labelled the remaining five motets as ‘De ecclesia Christi sponsa’, clearly not a description covered in Attaingnant’s rubric, but suggesting a non-Marian context for the performance of these motets. The texts of these five motets draw on the Song of Songs and the handwritten rubrics clearly emphasise the interpretation of these texts in the light of Mary (or the bride) as the Church. Since Attaingnant’s rubrics coincide with the Parisian traditions for these texts (though they are more general than most liturgical sources, which specify, for example, the Feast of the Assumption, or Octave of the Assumption), and the liturgical and devotional use of the texts is almost universally connected to feasts for the Virgin (or a virgin), the owner may in this case have been recording an alternative use for the motets.Footnote 48 Considering the different assignments that the owner indicated for these ten motets (which includes using the second part of Gascongne’s motet for Francis I as a motet ‘De Christo’), and the references to the French king and apostle, we can surmise that he did not follow the use of Paris and that Attaingnant’s rubrics represent, to some extent, a local tradition.Footnote 49

Given that Attaingnant was first and foremost a businessman, it is not surprising that his rubrics were often general enough to accommodate many different uses. The additions in the Jena copy of the series and the wording of some of the rubrics, and the contents of the books themselves, show us that they represented a specific local tradition, one which often coincided with the use of Paris, from liturgical to devotional, or even traditional use. The rubrics allow for many possible functions for the motets and actually provide some insight into the classification of pieces as motets in sixteenth-century Paris.

THE FUNCTION OF THE MOTET REVISITED

The question of what exactly constituted a motet in the sixteenth century and what function motets served has occupied modern scholars for several decades and has led to various and often competing theories. One theory, proposed by Jacqueline Mattfeld, gave the motet a liturgical function: the motet would be sung as part of the liturgy in place of the text that it set.Footnote 50 This view was largely supplanted in the 1980s when several scholars, notably Anthony Cummings and Jeremy Noble, proposed a paraliturgical function for the motet: where it would adorn the liturgy but was not essential to its performance.Footnote 51 Within the paraliturgical function, we also find a use for motets in processions and at stational liturgies. Robert Nosow proposed that motets used in processions or stational liturgies served a ceremonial function, one which added drama and interest to the liturgy, and Noel O’Regan found that polyphony, and motets in particular, were standard components of processions in late sixteenth-century Rome.Footnote 52

A third point of view gives the motet a devotional function, whereby it was performed in private or semi-private venues, like the home or confraternity. The view of the devotional function of the motet within a paraliturgical context was advanced by Howard Mayer Brown in his discussion of the first printed motet anthologies published by Petrucci.Footnote 53 He found that many of the texts of these motets were common in private devotional books. More recently, Julie Cumming found a high proportion of texts from these anthologies in books of hours.Footnote 54

The fifth view of the motet, which gives it a multipurpose function, was proposed by Julie Cumming after an extensive study of motet sources from the fifteenth century and the theoretical writings on the motet by contemporary theorists.Footnote 55 It allows for the functions described above, but does not limit the function of the motet to a single context. Instead, it gives the motet a flexibility of function. Cumming also accepts a distinction between liturgical polyphony, which has a prescribed function, and the motet, which has no prescribed function but rather many possible uses. This accommodates stories of motets being sung as entertainment, like the account in the diaries of the Sistine Chapel, which states that motets were sung at the pope’s dinner table.Footnote 56

The title page of book 7 sheds light on what function motets served for Attaingnant. In the instructions, he refers the reader back to the fifth book of motets (‘ad quintum librum motetorum’), referring of course to book 5 containing Magnificats. Attaingnant clearly thought of these pieces as motets, in naming them as such here and in including two books devoted exclusively to this type of setting as part of his numbered motet series. However the majority of these Magnificats were almost certainly composed for liturgical use at the French royal court, and the term motet was not typically associated with this kind of simple, alternatim polyphony. We could conclude from this and the relation of the rubrics to both liturgical and devotional books that for Attaingnant at least, motets could encompass a wide range of pieces and could serve a variety of different functions; even prescribed liturgical music, like Magnificats, could be used for devotions as well. The fact that he included motets on texts found exclusively in devotional books, or even in books of sacred and secular Latin poetry, attests that this was not just a collection of polyphonic works for liturgical use, but that it represented the full range of sacred Latin-texted music outside the Mass. The inclusion of rubrics throughout served a double purpose: to make evident the subject of the piece for the uninitiated, but also to indicate a specific occasion for the performance of the motets without limiting their performance to a specific context. The question remains as to which tradition of performance or use Attaingnant was promoting in the series. Was he indeed reflecting and promoting the local Parisian use, or was he making the series more universally appealing? Interestingly, he appears to have done both.

SINGING THE KING’S MUSIC?

We saw that the title rubrics and organisation of certain books correspond to the use of Paris, particularly books 7, 10 and 12. Yet the connections to the use of Paris are not explicitly stated, nor do the rubrics preclude the possibility of using the motets for a variety of occasions. As we saw in the case of book 12 and the individual rubrics, most rubrics are quite general and unrestricting in their wording, even when they clearly represent local traditions. Indeed, there is no clear evidence that Attaingnant was relying exclusively on the court or local composers for his repertory, and several of the motets were composed for specific events or patrons outside of the court network, thereby expanding the original context of the motets.Footnote 57 There is compelling evidence, however, to connect the series to the French royal court. While the rubrics themselves were probably coined by Attaingnant (or someone in his atelier) and the wording of the rubrics in the series is generally similar to that found in books outside of Paris, many of the rubrics and the use which Attaingnant suggests for the motets correspond to those found in liturgical books used by the royal chapel or other institutions frequented by the royal family, such as Notre-Dame de Paris and the Sainte-Chapelle du Palais.Footnote 58 Many of the texts of the motets were also included in royal chapel liturgical and devotional books.Footnote 59 Additionally, the fact that Attaingnant’s editions in general contain a large proportion of works by court composers, and that this series in particular features many works by court composers and those employed at other institutions which the king frequented, clearly links this series to the court and to Francis I.Footnote 60 Of the sixty named composers in Attaingnant’s motet series, twenty-five had clear ties to the French royal court, Sainte-Chapelle or Notre-Dame de Paris; 155 of the 281 motets in the series, more than 50 per cent, were attributed by Attaingnant to these twenty-five men. Attaingnant’s own tie to the court was implicit at the time of printing, when he was the only printer of music in Paris and his editions were protected by royal privilege, a fact he advertised on the title pages of his series.Footnote 61 His tie to the court was made explicit three years later when the king appointed him the first Royal Printer of Music. Perhaps then, part of the tradition preserved in the series is that of the French royal chapels. That motets and polyphony played an important role in the king’s own liturgical and devotional observances is clear from the changes that he made at the important centres of sacred polyphony in Paris, specifically to the royal chapel, which is attested to by historical accounts of the court.Footnote 62

In the first decade of his reign, Francis I oversaw major changes to the organisation of the royal chapels, which visibly influenced the daily performance of music at the court. The queen’s chapel had already been absorbed into the king’s chapel following the death of Anne of Brittany in 1514, bringing the total number of singers in the king’s chapel to twenty-three.Footnote 63 By the late 1520s to early 1530s, the king’s chapel was restructured into two entities: the Chapelle en Musique and the Chapelle de Plain-Chant.Footnote 64 The Chapelle en Musique was the larger of the two and often travelled with the king. It was responsible for the singing of polyphony at High Mass and Vespers on feast days and at various other times and unspecified locations. The smaller Chapelle de Plain-Chant was required to remain at the court and perform daily High Mass and Low Mass, as well as services for the canonical hours, whether the king was present at court or not.Footnote 65 By 1578, the chapel rule stipulated that the Chapelle en Musique was also responsible for singing at Vespers and Compline on Saturdays and Sundays, and in 1585, the rule stipulated that it was also responsible for the singing of the Salve service after Compline.Footnote 66

Historical accounts of Francis I’s rule by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century authors highlight these changes and also mention public occasions on which the king’s singers performed polyphony, and more specifically, motets. In the historic meeting of Francis I and Henry VIII at the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520, the two rulers heard a private High Mass during which their singers performed.Footnote 67 At the conclusion of this service, the French singers sang several motets.Footnote 68 At the 1532 meeting between the monarchs in Boulogne, the French singers again performed several motets. According to Alfred Hamy and Louis Archon, separate Low Masses were said for each king inside Notre-Dame de Boulogne.Footnote 69 The French king arrived late and heard only one Low Mass, ‘pendant laquelle les chantres chantoient des motez’.Footnote 70

The singing of motets during Mass does not appear to have been limited to these occasions, but was apparently a staple of Francis I’s daily observances. Claude Chappuys, librarian and valet de chambre of Francis I, mentions the singing of polyphony during Mass as a daily occurrence in his Discours de la court printed in 1543:

Chappuys indicates here that the singing of motets (and psalms) was a daily feature of the king’s Mass. According to the rules for the two chapels, daily Mass for the court was performed by the Chapelle de Plain-Chant, which did not perform polyphony. The singing of motets would therefore have been performed by the Chapelle en Musique, but not as part of the daily Mass. Francis I’s partiality for motets during Low Mass was observed at both Boulogne and the Field of Cloth of Gold; at the latter, Low Mass was read at the same time as the High Mass, but at a private altar for the king. According to Étienne Oroux’s ecclesiastical history of the court, the 1585 chapel rule stated that every day the king is present at court, a High Mass is to be said, and at the same time two Low Masses should be said as well.Footnote 72 This practice would seem to agree with the accounts we have of the simultaneous High Mass and Low Mass that Francis I heard at the Field of Cloth of Gold and would account for the daily singing of motets as part of the service for the king. Indeed, the performance in France of a public High Mass for the court, while a private Low Mass was read for the monarch, appears to date back to the fourteenth century.Footnote 73 It could very well be that while the Chapelle de Plain-Chant performed daily High Mass for the courtiers, the Chapelle en Musique performed motets for the king’s Low Mass.Footnote 74 The fact that the king heard motets as a daily part of his observances would surely have been generally known before Chappuys’s account in 1543, which mentions the fact as a matter of course. The fact that Claudin de Sermisy is lauded for his motets is significant; not only was he the sous-maître of the Chapelle en Musique, but of the composers featured in Attaingnant’s series, Sermisy is the most represented, with twenty-five motets.Footnote 75

If the singing of motets during Mass was performed exclusively for the king and not heard by the whole assembly, there were, however, several occasions where royal singers performed motets for a broad Parisian audience. At least two public processions were ordered by Francis I in the 1520s and 1530s, both of which featured the singing of motets by the royal singers.Footnote 76 In response to an act of vandalism of a statue of the Virgin and Christ Child in Paris, the king ordered all ecclesiastic establishments in the city to lead processions against the sacrilege.Footnote 77 After Mass on 11 June 1528, on the feast of the Holy Sacrament, the king and his court went to the site of the damaged statue. Once there, the singers of the Chapelle en Musique performed the antiphon Ave Regina.Footnote 78

A second large-scale procession occurred in 1535, part-way through the printing of Attaingnant’s motet series, in response to the infamous Affair of the Placards on 18 October 1534.Footnote 79 On 21 January 1535, a general procession marched through Paris:

Tous les Couvents et les Chapitres s’y trouvèrent, avec les principales Reliques de leurs églises. Après les Religieux de Sainte-Geneviève et de Saint-Victor, marchant les uns à côté les autres, venoit le Chapitre de Notre-Dame, avec les églises qu’on appelle ses Filles, à main droite; le Recteur et l’Université à la gauche: puis, marchoient les Suisses de la garde du Roi, les hautbois, violons, trompettes, etc. Ensuite, les Chantres de la Chapelle de Sa Majesté, tant les domestiques, que ceux de la Sainte-Chapelle du Palais, mêlés, et chantant cantiques et motets. L’évêque de Paris portoit le Saint-Sacrement sous un dais, qui étoit soutenu par le Dauphin, les deux Princes ses frères, et le duc de Vendôme. Le Roi suivoit immédiatement, tenant une torche à la main, et édifiant tout le monde par les démonstrations de la plus tendre piété.Footnote 80

Here, as in the procession in 1528, the king and his singers participate in public processions where motets are performed.Footnote 81 His singers perform motets as they did during the king’s daily Mass and at the meetings with Henry VIII. Surely some of these motets could have found their way into Attaingnant’s hands. Court and Parisian composers figure prominently in the series, and it is likely that some of these pieces would have been performed either at the daily services heard by the king, in the Sainte-Chapelle or in Notre-Dame de Paris, or during these public processions.Footnote 82 If we accept that Attaingnant was to some degree printing the king’s music, an assertion proposed by Daniel Heartz and almost universally accepted, the function of the series and its motets takes on a different role. By allowing the populace to partake of the king’s music and by allowing the public to participate and share his musical experience, Attaingnant was perhaps acting to extend the reach of the king’s influence beyond his court and beyond Paris. In addition to, or perhaps in spite of, its liturgical and devotional connections, the real point of the series may simply be this: here’s how we do it in Paris. Here are the motets we sing at these times, that the king hears on these occasions. And now you can sing them at these times also, cum gratia christianissimi Francorum regis.

APPENDIX

Individual Rubrics in Attaingnant’s Motet Series