When I was growing up, there was no internet. Luckily, I had Dad. My father Tom McArthur was my search engine long before Google existed, answering questions that kept me awake at night, often with long, intricate stories. If he didn't know an answer, he would consult one of the many dictionaries and reference books that lined the shelves of our home. There was no such thing as a casual question with Dad; he took my curiosity very seriously.

Dad had an encyclopedic mind, with a library to match. When my sister Meher was about ten years old, she took on the daunting task of counting his books, and she remembers reaching a dizzying one thousand. That was before he founded English Today as editor, and multiple books started landing on our doorstep daily. By that point, we had long since stopped counting.

He read books and newspapers voraciously and constantly, highlighting words, phrases, and cultural references that caught his eye, and he seemed to remember every word.

Dad's life echoed his mind and defied summary. When I wrote his obituary for The Guardian newspaper earlier this year (McArthur, Reference McArthur2020), I found it next to impossible to summarize his encyclopedic travels, achievements, and personality in the allotted 400 words. My friends read the finished product and commented on how prolific he was, but they had no idea what I'd had to leave out.

From left: Feri, Meher and Tom in Bombay, India, 1967

A global Scot

It might have been easier if he had stayed in one place, but that wouldn't have been Dad's style. He started his life in a Glasgow tenement and regularly unnerved his mother by hitchhiking to far-flung places like Morocco. In a kilt. He became the first person in his family to attend university and was forever dubbed ‘the clever one’.

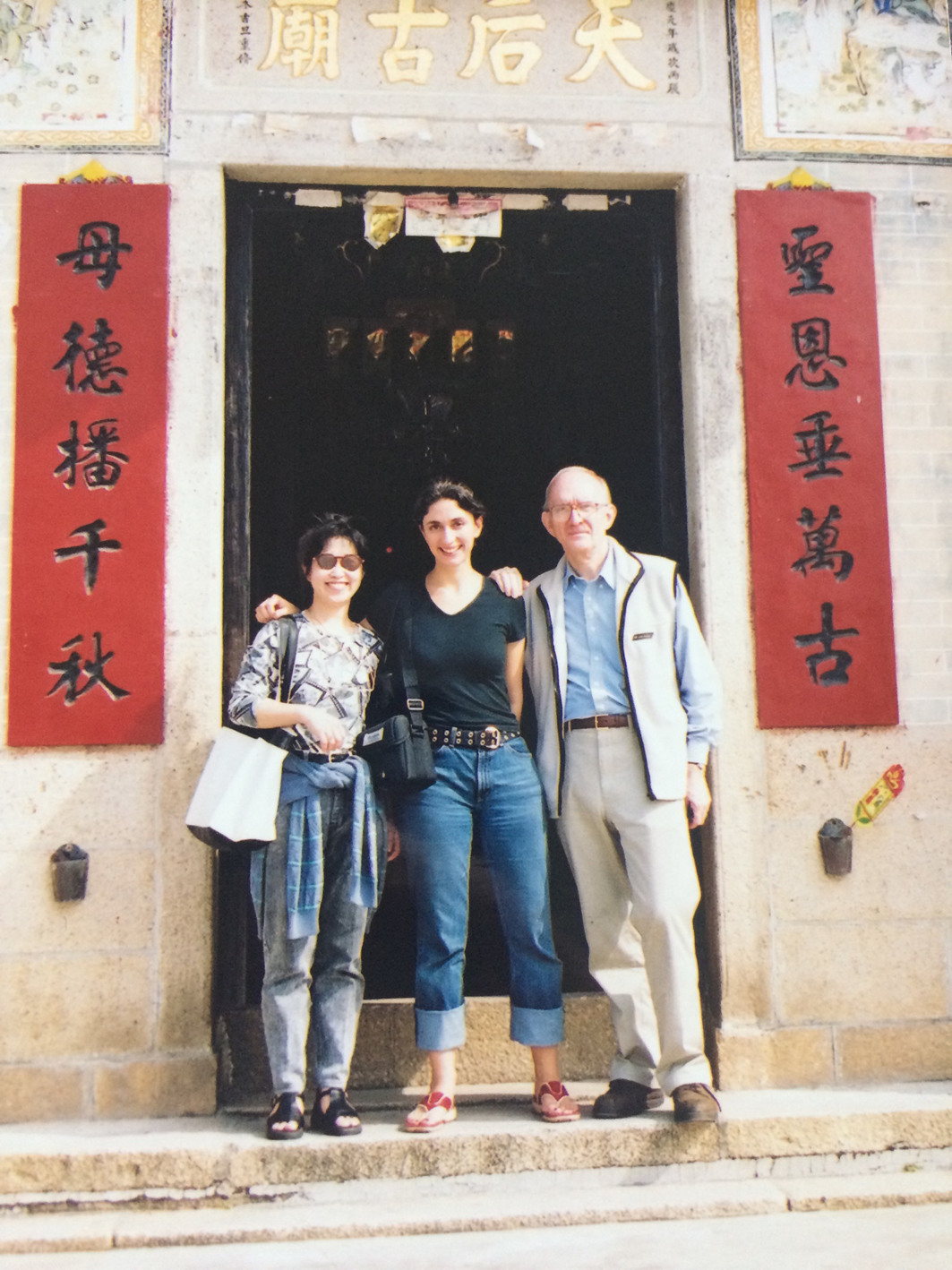

He moved to England, and once again defied tradition by marrying a brown woman, my mother, Iranian-born Feri Mottahedin. His mother was so upset by his choice that she boycotted the wedding. Undeterred, my parents travelled the world, moving to Bombay (where my sister was born), to Edinburgh (where my brother Alan and I were born), to Quebec, and to Cambridge. He encouraged us to believe that, as nomadic, mixed-race kids, we were citizens of the world. After Mum died in 1993, he married Jacqueline Kam–Mei Lam, a native of Hong Kong, and moved there to be with her.

Dad was remarkably global and expansive in his interests, not only writing about English as a world language but also creating course books and dictionaries, promoting the languages of Scotland (McArthur & Aitken, Reference McArthur and Aitken1979), writing books on yoga and Indian philosophy (McArthur, Reference McArthur1986a; Reference McArthur1986b), and dabbling in self-help (McArthur, Reference McArthur1988). He devoured episodes of Star Trek, so it wasn't altogether surprising (to his family, at least) that he once proposed a Star Trek encyclopedia to Oxford University Press. It never saw the light of day, and neither did his many novels . . . but that is literally another story.

Our lives were filled with words. We were quite possibly the only small children in the world in the mid-Seventies who knew what a phrasal verb was, thanks to one of the first books Dad worked on (McArthur, Reference McArthur1973). We knew the two most useless words in the English language: dolabriform, meaning ‘shaped like the head of an ax’, and pennigerous, ‘bearing feathers’. We knew that there were separate words in Russian for dark and light blue (синий and голубая, in case you're interested). We collected the numbers one to ten in as many languages as we could . . . because that's what you do when your father is a linguist.

Then there were the Scots Evenings at Edinburgh University. My decidedly un-Scottish-looking brother, sister and I were decked out in tiny kilts as the Persian Highlanders, and sang songs to international students in a language we didn't understand, Gaelic. We were there, between Burns poetry and bagpipes, to provide the cute factor. Dad always had a knack for levity.

In fact, when we were teenagers, he decided to present us with Honorary Citizenship of Glasgow awards when we each achieved a certain degree of wit. I remember getting mine at age 12, in response to his question: ‘What's brown, rustles, and climbs Notre Dame?’ It was, of course, the Lunchbag of Notre Dame, and I had arrived.

At around the same time, Dad despaired at the lack of classical education in schools, so he decided to teach us Latin. The three of us spent Saturday mornings learning to conjugate amo, amas, amat, amamus, amatis, amant, and more importantly studying Greek and Latin roots. For teenagers, it was a strange way to spend weekends, but he was right. Those roots have proved to be extraordinarily useful, not least for conjuring up puns.

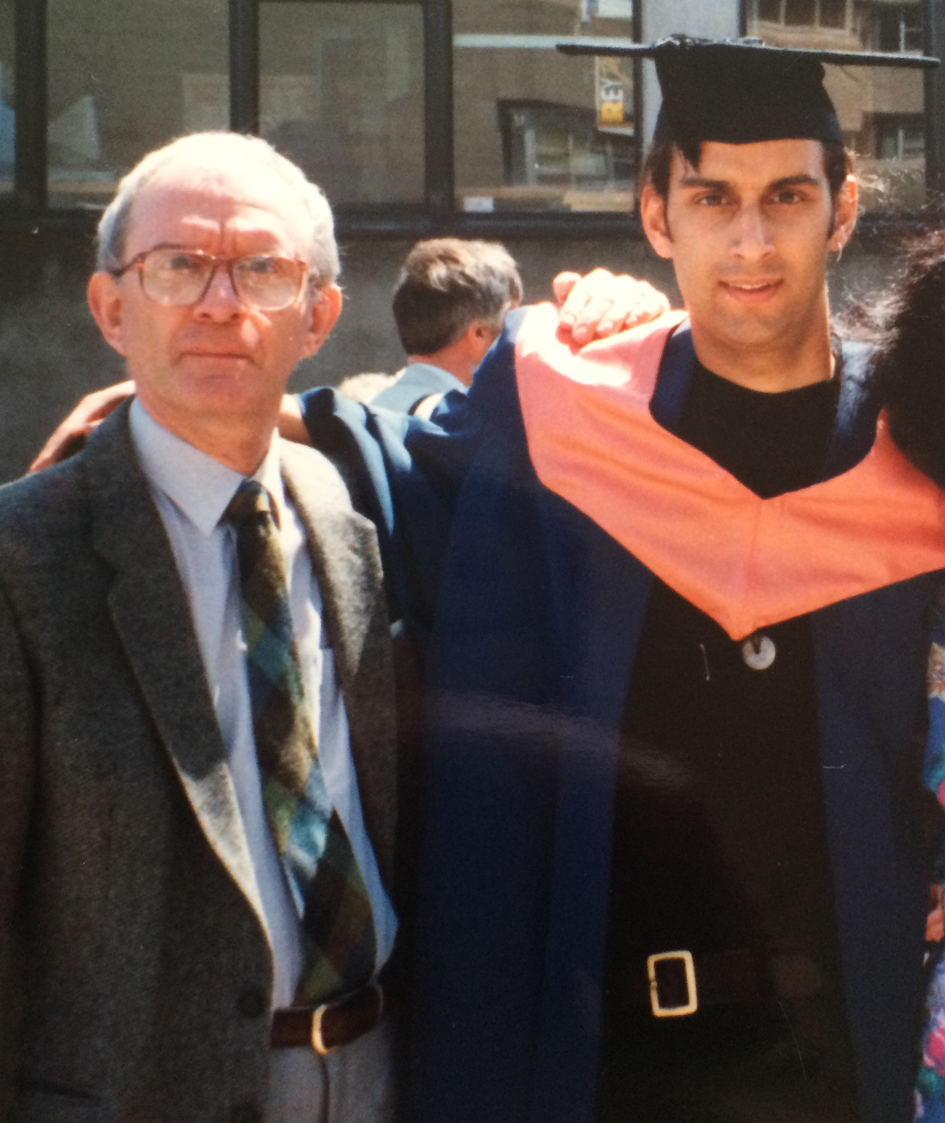

Tom with Alan at his graduation from the University of East Anglia, England, in 1992

An adventurous companion

Of course, when Dad wasn't teaching us dead languages, he was writing books. When I was about eight and Dad was compiling The Longman Lexicon of Contemporary English (McArthur, Reference McArthur1981), I remember index cards everywhere in the house, and him paying me and my siblings to sit on his office floor alphabetizing them. When I was a teenager, he asked me to read drafts of his books and give him my feedback. One night, we were watching a TV miniseries called The Winds of War, and I'm not sure who twisted the title into The Wands of Wir, but we decided that would be a great name for a Tolkienesque novel. Which Dad then wrote. It became The Seven Wands, the tale of Orm, a young Norse lad who yearned for adventure – and got far more than he bargained for.

That was Dad. And that was my childhood.

Years later, I worked with him on English Today and The Oxford Companion to the English Language (McArthur, Reference McArthur1992). He taught me how to edit journal articles with kindness, respecting the individual behind the words. He was a great defender of unique voices and an advocate for the up and coming.

We spent many hours turning the Companion first into an abridged edition, then later into a concise edition – a process that Dad didn't especially enjoy. He had poured his heart and encyclopedic brain into the original, and it was a painstaking and thorough volume.

To fully understand the Companion, you had to know Dad. The English language, for him, was everywhere, connected with everything we say and everything we do. So there had to be entries for Scots, for Gaelic, for Latin and Greek, for the media, even for humour. Left to himself, he might have found a way to work Spock into it, but he was also a realist and knew where to draw the line.

From left: Tom, Roshan and Jacqui in Hong Kong, 2001

Lost for words

I always wondered what it would be like to lose Dad. Growing up, I relied on him for answers and was in awe of the breadth of his knowledge. To spend so long compiling the encyclopedia that was his mind, and then lose it, seemed to me unspeakably cruel. I just couldn't imagine it ceasing to exist.

In the end, it happened very slowly. He started losing words one at a time, then he found it harder and harder to string thoughts together. The father I had known began to fade, which gave me time to absorb the loss.

Because we took him seriously about being citizens of the world, my siblings and I were in different countries when he passed away in March, and because of COVID–19 we were unable to travel to Cambridge to mourn him.

At the time of writing, more than three months have passed, and I still haven't been able to leave my home in Los Angeles, but that time has allowed me to reflect on his legacy. It has been a pleasure to discover that he touched many lives. I've received a range of messages from his students at Cathedral School in Bombay as well as eminent lexicographers he worked with, all of whom have shared the positive effect he had.

Me, I've found him inside myself, in my obsession with the written word. In writing the term COVID–19 above, I thought about how Dad would have highlighted every mention of this newly-coined expression in the newspapers he read. I know he would have enjoyed explaining how the word coronavirus is derived from the shape of the sun, and how quarantine comes from the Latin root for 40. He would have followed the debate on globalization and pandemics with great interest.

My father was a maverick, and his was a life well lived. He believed passionately in a non-elitist, inclusive world where all Englishes had their unique place (McArthur, Reference McArthur1998), and he also believed all reputable scholars deserved the opportunity to shine. I am pleased that he had English Today as a platform for so many years because it allowed him to share that worldview and pass it on to younger academics.

I hope that the journal continues sharing his legacy for many years to come. It would be a fitting tribute.