Introduction

Globally recognized consumer goods such as Danish design furniture, Swiss watches, and Parisian fashion are some of the examples that demonstrate the importance of strong national identities for internationalization. However, the relationship between companies’ branding strategies to nation-building and nation-branding, especially in the context of former colonies whose national identities were being reconfigured in the postcolonial era, remains underexplored. Using the case study of Royal Selangor International Sdn. Bhd., this study tracks how a Malaysian pewterFootnote 1 company (see Figure 1) utilized international branding strategies to position itself above the polemics of national identity arising from its Chinese family business identity and overcame limited resources and social networks from the 1970s to the 1990s to become the world’s largest pewter manufacturer and a national symbol of the country’s economic development.

Figure 1. Tableware designs from Selangor Pewter in 1966 (left); a teapot with rattan handle designed by Danish designer Erik Magnussen in 1986 (right).

Source: Royal Selangor Company Archives. Used with permission.

This study engages with theoretical frameworks of business history, organizational studies, and nationalism to explore how businesses in former colonies draw upon cosmopolitan worldviews of malleable identities from the colonial era to create economic change amid transitioning ideas on national identities and economic development in the postcolonial era. In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson argued that nationalism is essentially “imagined,” bound by socially constructed narratives of rulers and governments using artifacts such as the census, maps, museums, and print culture.Footnote 2 The case study of Royal Selangor provides empirical evidence on how businesses adapted to shifting ideas of national identity in the postcolonial context by utilizing the legacies, narratives, and designs of Britain (Malaysia’s former colonizer) as branding strategies to gain cultural capital locally and for exports in Western markets. This differs from Hansen’s study on the success of Danish modern in the U.S. market in the 1950s and 1960s, as the social construction of powerful narratives by Danish furniture designers, producers, and networks were premised on the existence of a strong Danish national identity and cultural heritage.Footnote 3

Royal Selangor was established in 1885 in the tin-rich Selangor district—then part of Malaya, a British colony whose main commodity exports were tin and rubber. The company is currently managed by the third and fourth generation of family members of Chinese ethnicity (the largest minority group in multiethnic Malaysia). Known as Selangor Pewter between 1942 and 1992, it is one of the country’s earliest own brand manufacturers whose “Made in Malaysia” pewter products are based on original designs—bucking a trend of typical businesses in former colonies in producing and exporting generic commodities inherited as colonial legacies.Footnote 4 Between the 1960s and early 1990s, it grew exponentially from a small family enterprise to a medium-to-large enterprise of about six hundred to one thousand employees and entered the British market in 1987. Despite Britain’s diminishing pewter industry in the postwar era, its long history in pewter manufacturing before the Industrial Revolution and national cultural legacy tied to pewter made the market a symbolically important one. With exports to more than twenty countries, the Royal Selangor brand is generally viewed by Malaysians as a national symbol. The national government also acknowledged its capabilities and commissioned the company to design various interior and exterior decorations for its offices and compounds.Footnote 5

This study shows how a company’s international branding strategies became part of the processes of nation-building and nation-branding, which Jørgensen and Mordhorst described as two related processes undertaken through institutionalized efforts by governments and cultural institutions to create positive national images of a country.Footnote 6 A micro-level firm analysis of Royal Selangor demonstrates that global branding through a royal warrant and the company’s focus on European-looking designs are not only for internationalization, but also to elevate its corporate image as a respected cultural marker in Malaysia. The company constructed a malleable identity that enabled it to gain a foothold in Britain and Australia more easily through designs and narratives familiar to consumers. However, this identity is also paradoxically “national” in character, which helped to preserve the family’s ownership and control of the business amid political tensions surrounding racial identities arising from capital redistribution policies and the government’s shift in focus to high-technology and capital-intensive industries during the 1970s and 1980s.

This study draws from various primary sources encompassing newspaper articles from the 1930s to the 1990s, archival materials from company files, correspondence obtained by the designers that the company hired during the period, and oral history interviews with the third-generation owners and managers of Selangor Pewter/Royal Selangor. A key secondary source is a commemorative company history—The Royal Selangor Story: Born and Bred in Pewter Dust—published in 2003, which also described the development of its branding processes.

The Intersection Between Branding, Business, and National Identity in the Postcolonial Context

Companies’ use of history, as management scholars Suddaby, Foster, and Quinn-Trank argued, is “a strategic organizational asset” that organizations use for commercial objectives such as international expansion and brand rejuvenation to capture new markets and audiences.Footnote 7 Across the globe, business historians have described how global brands (Heinz, Cadbury, and Nestlé), as well as luxury fashion brands (Moët Hennessy, Louis Vuitton, Gucci, and Christian Dior), have broadly utilized narratives or storytelling—often focusing on an origins story told retrospectively, and as such, the use of history—as strategies for brand-building.Footnote 8 Nevertheless, these historical analyses have been on global brands developed in industrialized Western economies, thus presuming that the developmental patterns of global branding and their objectives are the same, even though brands are much more complex and multifaceted when operationalized.Footnote 9

An underappreciated nuance in brand-building processes is that organizations pivot on nation-specific contexts as part of their strategies. For instance, Khaire and Wadhwani showed that the appreciation in value of twentieth-century Indian art depended on a collective and conscious effort by museums, curators, and journalists in categorically distinguishing Indian art from Western modern art, thus elevating its status in the process.Footnote 10 Delmestri and Greenwood’s case study of Italian grappa shows how a historically low-status alcoholic beverage can be transformed to the status of cognac and whiskey (of which the most established brands are made in France and Scotland, respectively) in just over a decade by anchoring to “higher-level cultural narratives” to provide “the necessary legitimacy.”Footnote 11 Further, Hansen’s research on the internationalization of Danish modern furniture shows how the messages of simplicity and functionality of furniture design were adapted to the popular cultural narrative of mid-twentieth-century American pragmatism.Footnote 12 These case studies, however, treat the national identity as a prerequisite and given, rather than a continuous process of renegotiation and reconstruction, as Jørgensen and Mordhorst argued.Footnote 13

Anderson argued that Southeast Asia—most countries of which were once colonies of Western imperial powers—had its antecedents of national identity construction formed through colonial imaginations of identity categories that became visibly more racial over time.Footnote 14 Colonialism’s systematic and binary categorizations of commodities and identities, however, overshadowed the cosmopolitism displayed by the urban societies in the region, arising from its long history of maritime commerce and interactions among various ethnic and religious groups in the precolonial era. Through her studies on colonial port cities of Penang, Bangkok, and Rangoon, Lewis argued that cosmopolitism of Southeast Asia is not “imagined,” but evolved through negotiations made possible by the urban society’s embracing of malleable identities, cultural pluralism, and openness to nonlinear learning processes and ideas.Footnote 15 Lees’s study on Malaya’s social and economic life in colonial-era plantation estates also stressed the blurring of relationship boundaries in the colonial society—the relationships between the colonizer and the colonized “were not only flexible, but also permeable in many settings, although inequalities of power twisted interactions in fundamental ways”—thus contradicting mainstream arguments of imperialism as organized governance systems.Footnote 16

In Malaya and Singapore, as Frost shows, the rising class of locally born or permanently settled Chinese business community leaders—especially the Straits Chinese in Singapore in the early twentieth century, built social capital and new business opportunities by asserting their flexible identities as Anglo-Chinese with multiple political and cultural allegiances.Footnote 17 The proximity between Malaya (renamed Malaysia in 1963) and Singapore meant that transmission of ideas concerning cosmopolitism were generally seamless, as both colonies shared connectedness through English-language newspapers, demography, and complementary roles as hinterland and entrepôt economies under the British Empire.Footnote 18 This nuance matters, as Foster pointed out, because it sheds light on how colonial and postcolonial societies made sense of production of commodities, branding, and consumption to reconfigure their national identities and places in the global economy.Footnote 19 Trivedi’s study of the transformation of the khadi cloth in India from an ordinary, locally made product to a national symbol and resistance against colonial rule in the 1920s and 1930s also elucidates how products as national symbols occupy the public imagination.Footnote 20 Nevertheless, from the 1950s, the nationalism that swept across newly independent countries utilized the rhetoric of rapid economic development for nation-building projects.Footnote 21

This brand of nationalism mainly involved the replication of Western industrialization in high-technology and heavy industries, while sidelining the crafts industry that did not fit into the image of being “high-growth,” thus deepening the disconnect between locally made products, branding, and design.Footnote 22 In Malaysia, the entrenched image of the crafts industry as low-tech and labor-intensive with minimal capital input requirements has its roots in colonialism. As a policy of “mitigated modernity,” the British colonial government blocked Malays—the native and majority population living in the rural areas of the colony—from participating in the main economy in tin and rubber but encouraged some of them to pursue entrepreneurship in handicrafts industries (such as silverwork and handloom weaving) to increase the community’s earning power beyond the agricultural subsistence economy.Footnote 23 The colonial administration issued certificates of authenticity as an early branding initiative and sent samples to Europe, Canada, and the United States for potential exports, but Cheah argued that by emphasizing the preservation of Malay crafts’ heritage status rather than increasing their commercial viability through technological upgrading, craft production became associated as low-tech “rural work.”Footnote 24

Against this backdrop, business development in postcolonial Malaysia often tracks the reconfiguration of national identity, especially after the 1970s, following an increasing emphasis on pro-Malay policies that vexed the Malaysian Chinese community. Nonini argued that most Chinese living in Malaysia “saw themselves as affiliated, connected, and loyal to the Malaysian nation, although they were unsure to what extent it was to be defined as their nation.”Footnote 25 These theoretical frameworks on nationalism show how shifting ideas on national identities have significant impact in the social and economic development of a society. Nevertheless, how businesses, particularly local firms in former colonies, address shifts on national identities through their strategies has not been studied. In business history, nationalism has often been classified as “political risk,” and most scholarly attention is paid to how large, Western enterprises dealt with it.Footnote 26 Most studies on Southeast Asian businesses concentrated on large and diversified Chinese business groups whose adaptation to nationalism was mainly displayed by forming patronage relations with the state—and through investments in few highly regulated sectors such as banking, plantations, gaming, telecommunications, and retail property—and thus projected a belief that all Chinese businesses adopt the same strategies.Footnote 27

In recent years, there have been more attempts by Malaysian economists and historians to widen the scope of analysis of Chinese enterprises, out of which two historical studies on Royal Selangor stood out, but their analyses lacked detail and remained fixated on the importance of Chinese networks. For instance, Gomez and Wong argued that the family business’s success is determined by its “ability to develop a brand identity,” and they attributed product innovation and effective marketing to its export growth but presumed that the company already had sophisticated know-how before it internationalized.Footnote 28 Historians Cheong, Lee, and Lee compared Royal Selangor and the Kuok Group—a conglomerate in commodities manufacturing and luxury hotels sector headed by Malaysian Chinese tycoon Robert Kuok—to argue the importance of differences in their subethnic identities (Hakka and Teochew, respectively) in determining the companies’ internationalization strategies, but those authors did not analyze how these strategies contributed to Malaysia’s metanarrative on economic development and postcolonial nation-building.Footnote 29 By focusing on the use of history in narrative construction in a company’s international branding strategy, this research highlights an understated dialogue between nation-building and national-branding initiated by businesses operating in the postcolonial context and the intersection of business history, branding, and national identity.

The Malayan Pewter Industry in the Colonial Era

Tin is one of the oldest metals known to man, with artifacts from as early as 1300 BCE found in Egypt.Footnote 30 On its own, tin is a brittle metal, but when mixed with other metals, it transforms into a highly versatile alloy, such as pewter. The Chinese had a long history of interaction with tin, particularly for producing bronze in the first millennium, and subsequently produced pewter.Footnote 31 As pewterware production was ubiquitous in China since the seventeenth century, during the Qing Dynasty, Chinese pewter artisans in search of new business opportunities overseas in the early twentieth century were naturally drawn to Southeast Asia, foremost to Malaya, which was the world’s largest producer of tin.Footnote 32 The thriving tin industry spurred an influx of Chinese laborers, artisans, and merchants to towns in the Selangor district and Kinta Valley—along the west coast of Malaya, where the colony’s largest tin reserves were located—to set up small tin-related businesses, including pewter production.

Until the publication of a commemorative company history by Royal Selangor, little was known about the shape and structure of the early Malayan pewter industry. The company, using narratives passed down from previous generations of family member managers, described tinsmith enterprises as craft-based producers of a variety of everyday household items, such as pails and gutters made of galvanized steel and scales used by merchants.Footnote 33 Nevertheless, from 1930, Malayan tin miners encouraged the development of a local pewter industry to cushion the impact of falling prices from overproduction and the aftermath of the Great Depression of 1929.Footnote 34 In January 1932, prominent tin miner and capitalist Foo Wha Cheng tabled a memorandum at the Tin Propaganda Committee, later published in several English-language newspapers in Singapore, appealing to the colonial government to create a pewterware industry.Footnote 35

His appeal is quoted at length here:

Is it not possible to organise a systematic drive or campaign to advocate, encourage or “boost” the extensive buying and using of articles made from tin (Pewterware) so that an appreciable local demand could be created? If each household (tin mining companies) took ten catties of Pewterware, it would be observed that in course of time 5,000 piculs of tin would be thus used up in the Malay States alone, leaving the other backward States out of our reckoning.Footnote 36

European tin miners went on to highlight the existence of Malayan pewter enterprises. In an interview in the Times of Malaya, Gerald Hillsdon Hutton, the general manager of Anglo-Oriental (Malaya) Ltd,Footnote 37 showed various pewterware to journalists, all of which was bought “at a little Chinese shop in Kuala Lumpur,” referring to the family pewter enterprise that would become Royal Selangor.Footnote 38 The plan to have a large-scale pewter industry did not materialize. Nevertheless, the tin miners’ plea to the colonial government specifically benefited the pewter enterprise that Hutton introduced to journalists.

The enterprise was set up in 1885 by Yong Koon SeongFootnote 39 (1871–1952) and his brothers, who were already based in the colony. Koon Seong was just fourteen years old when he sailed from Shantou, China, to Kuala Lumpur, which later became the capital of Malaya, to start 玉和 (Yu He), which means Jade Peace in Mandarin and is read as Ngeok Foh in the Hakka dialect, spoken by one of the largest Chinese subethnic groups in southern China. The enterprise produced Chinese ceremonial vessels such as drinking vessels and teapots using pewter (see Figure 2); each product was stamped with the company name, as well as the words 足錫 (zu xi), or pure tin, guaranteeing the quality of its pewter items. Located in a new urban enclave and influenced by European tastes in pewter design, the family business switched from Chinese religious ceremonial vessels to making cigarette boxes, ashtrays, and beer mugs for the European consumers living in Malaya from 1930.Footnote 40 The enterprise started selling and exhibiting pewterware under the name Malayan Pewter in 1934.Footnote 41

Figure 2. Chinese-style candlesticks and drinking vessels produced by Ngeok Foh before 1930.

Source: Royal Selangor Company Archives. Used with permission.

Upon the request of colonial officer John F. Owen in London to promote this Chinese enterprise’s pewter products with European designs, the F.M.S Chamber of Mines—an influential organization representing tin-mining companies’ interests in Ipoh, of which Hutton was a committee member—sent a collection of pewter articles, including a tea set, some ashtrays, and beer mugs “for advertisement purposes.”Footnote 42 They were manufactured by a “Mr. Y. P. Pow of the Phoenix Bookshop, Yap Ah Loy Street, Kuala Lumpur”—Koon Seong’s eldest son.Footnote 43 These opportunities gave the pewter enterprise the first taste of manufacturing for a foreign market.Footnote 44 However, the momentum lost traction with the outbreak of World War II in Malaya from 1941 to 1945.

Beer Mugs and Tankards for Foreign Servicemen Before 1970

Yong Peng Kai (1915–1990), the third son of Koon Seong, had continued the family pewter business under various enterprises with his siblings after World War II. He pioneered Selangor Pewter Company, which became the only surviving business entity established by any Yong family member. Peng Kai, who was bilingual in English and the Chinese language and dialects, modernized the enterprise’s operations from 1951 with an assembly line and division of labor.Footnote 45 Selangor Pewter began as a nuclear family business—after school, Peng Kai’s children would take telephone orders, pack pewter products, and paint labels on boxes.Footnote 46 Peng Kai also recruited his wife Guay Soh Eng’s cousins and had about thirty employees, many of whom were female and handled the pewter polishing and packing work, while the men worked as craftsmen.Footnote 47 Born in the post–World War II era and witnesses to Malaya’s decolonization, all four of Peng Kai’s children—sons Poh Shin and Poh Kon, daughters Mun Ha and Mun Kuen—received their educations in missionary schools, whose medium of instruction was in English, and were actively involved in the company’s expansion and internationalization from the 1960s. When the family earned enough, they sent Poh Kon—the youngest son—to the University of Adelaide for a degree in mechanical engineering. The older three siblings learned the trade through networks they cultivated along the way. The roles that the children took on were informally assigned whenever the need arose and were largely gender specific (see Figure 3). Nevertheless, Peng Kai formed a partnership among himself and the children, regardless of gender.Footnote 48 The children had not gone into the business willingly but bowed to Peng Kai’s wishes.Footnote 49

Figure 3. Selangor Pewter’s organization chart for the years 1965–1968 as reported by newspapers. Compiled by the author.

Source: “Shopping in Aircooled Comfort, Family Skills Help Company Expansion,” Straits Times, August 1, 1968, 13.

In 1962, Selangor Pewter moved to Setapak, the suburbs of Kuala Lumpur, into a four thousand-square-foot factory, and into a period of euphoric growth for both the family business and, in the broader sense, the newly independent country, Malaya. Selangor Pewter’s products were popular among the British and Australian armed forces stationed in Malaya—a postcolonial arrangement to counter Communist insurgencies regularly occurring from 1948 to 1960. Throughout the 1960s, the enterprise advertised its pewter products in newspapers as “Malaya’s/Malaysia’s Gift to the World,” as the newly independent nation also promoted itself as a “warm and friendly country” with “palm-fringed beaches.”Footnote 50 Pewter tankards had a special status tied to the British pewter industry developed before the Industrial Revolution. Pewterware and utensils were most ubiquitous in English households in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but their demand dwindled with the introduction of other materials such as silver, glass, and ceramics into the kitchens and dining rooms of Western societies. Nevertheless, the alloy found a new appeal in the souvenir and gift industry, as the wider historical culture of tin in Britain was extended to its former colonies, including Malaysia, Singapore, and former dominions Australia and Canada, underscoring the enduring cultural transmissions from colonialism. A Selangor Pewter beer mug with engraving became among the most popular souvenirs among the armed forces—it was a mass-produced piece of metal, yet at the same time, was personal and filled with meaning (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Servicemen posing with a Selangor Pewter beer mug ca. late 1950s to mid-1960s.

Source: Royal Selangor Company Archives. Used with permission.

However, in 1967, as part of ending its “East of Suez” policy, Britain announced its intention to withdraw troops from Malaysia and Singapore, marking an end to a significant and steady stream of business for Selangor Pewter. Altogether, 26,000 British and Australian troops left Malaysia and Singapore in 1971.Footnote 51 With the shrinking of the domestic market, the company had to search for new customers and markets abroad, and hence new designs. Footnote 52

A Design Department That Focused on British Designs

As a small pewter enterprise with limited resources, Selangor Pewter’s design process was by and large ad hoc, with neither a systematic approach nor conscious creation of a consistent brand identity. This strategy, or rather, the lack thereof, had worked during the 1950s with a narrow range of products. The company’s chief designer was Peng Kai, known by employees as “the senior Mr. Yong,” who would also sometimes get new design ideas based on customer feedback. Later, Peng Kai hired an art instructor to coach the company’s future first in-house designer—the daughter of his wife’s brother, Guay Boon Lay (1951–). In 1969, the company sponsored Boon Lay for a twenty-month intensive design course at Bristol Polytechnic (formerly known as the West of England College of Art), demonstrating that British designs were the company’s priority. The course was specifically tailored to expose Boon Lay to the foundations of graphic and product design within the shortest time possible to help the family business save costs. When the polytechnic was informed that the family business also intended to diversify into gold and silver jewelry making, the school also arranged for Boon Lay to have a six-month crash course in silversmithing and jewelry making at the Jewellery School on Vittoria Street in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, renowned as the “Toyshop of Europe” in the eighteenth century.Footnote 53

In 1971, Boon Lay returned to Malaysia, when Selangor Pewter had started exporting to Australia less than a year earlier, and was negotiating to start a new joint-venture partnership with German pewter manufacturer Röders—also a family-owned pewter manufacturer. Röders, an established brand in Germany, came to Malaysia seeking to set up a factory to lower its production costs. Pewter made in Malaysia would be sold as Röders pewter in Germany. Demand for pewter in Western economies diminished, and Röders exited the business a decade later but passed on crucial technology in pewter casting in metal molds to Selangor Pewter, cutting production time for beer tankards.Footnote 54 Through this technology, the company started experimenting with pewter casting in molds made of various materials, leading to more intricate designs in fine gifts, as will be outlined in the later sections of this article. The company started a prototype design department with a three-person team headed by Boon Lay. Australia was the company’s first export market, and the studio’s main responsibilities were to come up with pewter designs tailored specifically to this market. The timing for export to the Australian market coincided with that country’s full employment from its resources boom, partly fueled by Japanese industrialization in the early 1970s.Footnote 55

Pewter tableware manufactured before the 1950s contained 10 to 15 percent lead, which was found to cause lead poisoning, giving pewterware a negative reputation and forcing pewter manufacturers worldwide to change the alloy’s composition. Poh Kon’s training in metallurgy enabled the company to respond to this change quickly by producing pewter with an alloy composition of 95 percent tin and a combination of other alloys such as antimony and copper, which also made the appearance of pewter brighter and shinier, like silver.Footnote 56 As it was cheaper and required less polishing work than silver, pewter found renewed acceptance in the flatware and tableware industry, a trend first observed in the United States—an example being Dansk Designs, whose retail sales rose to more than US$10 million annually from sales of tableware with modernistic designs following the popularity of the Danish modern furniture.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, Australian consumers had continued to appreciate tankards and beer mugs with “Old England” designs from the 1950s. The slower change of pace in consumer taste worked to Selangor Pewter’s advantage, as it gave the company time to learn about new tableware design trends, even as beer mugs and tankards continued to be relevant among Australian consumers.

In Australian department stores, Selangor Pewter was usually placed in the tableware department, alongside more renowned and prestigious brands such as Royal Copenhagen, Royal Doulton, and Wedgwood. Selangor Pewter introduced a new, shapelier line of wine goblets designed by Boon Lay that could be used as tabletop decorations and a water pitcher design inspired by the tulip flower in 1973, which became a best seller (see Figure 5).Footnote 58 Every pewter design was made first for the Australian market in mind, and if the products were popular, they would be marketed in Malaysia and Singapore.Footnote 59 This shows how consumer tastes in former colonies in the postcolonial era would continue to be guided by Western design trends that came with the perception of being more “modern” than locally inspired designs. Still in its early days, the design team headed by Boon Lay functioned as a support team to other departments until Danish designer Anders Quistgaard (1944–2000), who would also be Boon Lay’s future husband, officially came onboard and formalized the design department in 1977.

Figure 5. A Selangor Pewter brochure in 1971 (top); the Tulip pitcher that Boon Lay designed and debuted in 1973 (bottom).

Source: Royal Selangor Company Archives; Selangor Pewter Company Archives, Copenhagen. Used with permission.

“1885”—Applying the Use of History and Danish Modern into the Business

Lessons on the construction of narratives and designs from the Danish modern movement had been transplanted to Selangor Pewter in the 1970s and 1980s through a Danish designer whose family background was intricately tied to the internationalization process of Danish design in the United States. The story of the Selangor Pewter’s business origins was well known among its third-generation family managers, but it was not broadcast until 1976, following a serendipitous connection between the Malaysian pewter company and Anders Quistgaard, a young designer who found himself in Malaysia in 1973 because of his interest in wooden furniture design—the hallmark of the “Danish modern.” Quistgaard came from a distinguished line of Danish artists—his father was the famed industrial designer Jens Quistgaard, while his grandfather was a sculptor. Jens Quistgaard was the chief designer of Dansk Designs, an American flatware design company whose marketing and product development strategies were so successful that they have been textbook case studies at the Harvard Business School since 1971.Footnote 60

Until Quistgaard’s appointment in the company in 1976—first as product development consultant and designer and with full designation as house designer and product development adviser in 1978—Selangor Pewter’s brand identity was modest and reflected its home market rather than the company itself.Footnote 61 Between 1960 and 1967, the company mainly used the taglines “Malaya/Malaysia’s Gift to the World” to attract the tourists who flocked to Malaysia, and “Made of Straits Refined Tin” to reflect the purity and quality of Malaysia-produced tin. Quistgaard’s key contribution was externalizing the company’s history from the realm of its managers’ subconsciousness into a full-fledged brand identity. It began as a secret project—undertaken not at the headquarters and factory premises but at Peng Kai’s residence—to design and develop a new packaging for exports based on modular dimensions that fit exactly into an export pallet and thus save storage space and shipping costs.

Quistgaard created an entire concept of packaging for Selangor Pewter’s products, placing pewter products inside specially designed lapis lazuli–colored boxes and making them look prestigious and luxurious, as if they were designer products. Each box was imprinted with a patented diamond-shaped logo with the name of the company and the legend “1885,” symbolizing the year the pewter enterprise was supposed to have been established by Koon Seong, the founder of Ngeok Foh (see Figure 6). The actual year the business was set up could not be dated that precisely, family members revealed, as there was no business registration as proof of its existence.Footnote 62 But Quistgaard stressed that the reason to communicate a narrative of the business’s longevity was beyond aesthetics, as it would differentiate the company from its rivals.

Figure 6. Selangor Pewter packaging from the 1980s, designed by Quistgaard.

Source: Royal Selangor Company Archives. Used with permission.

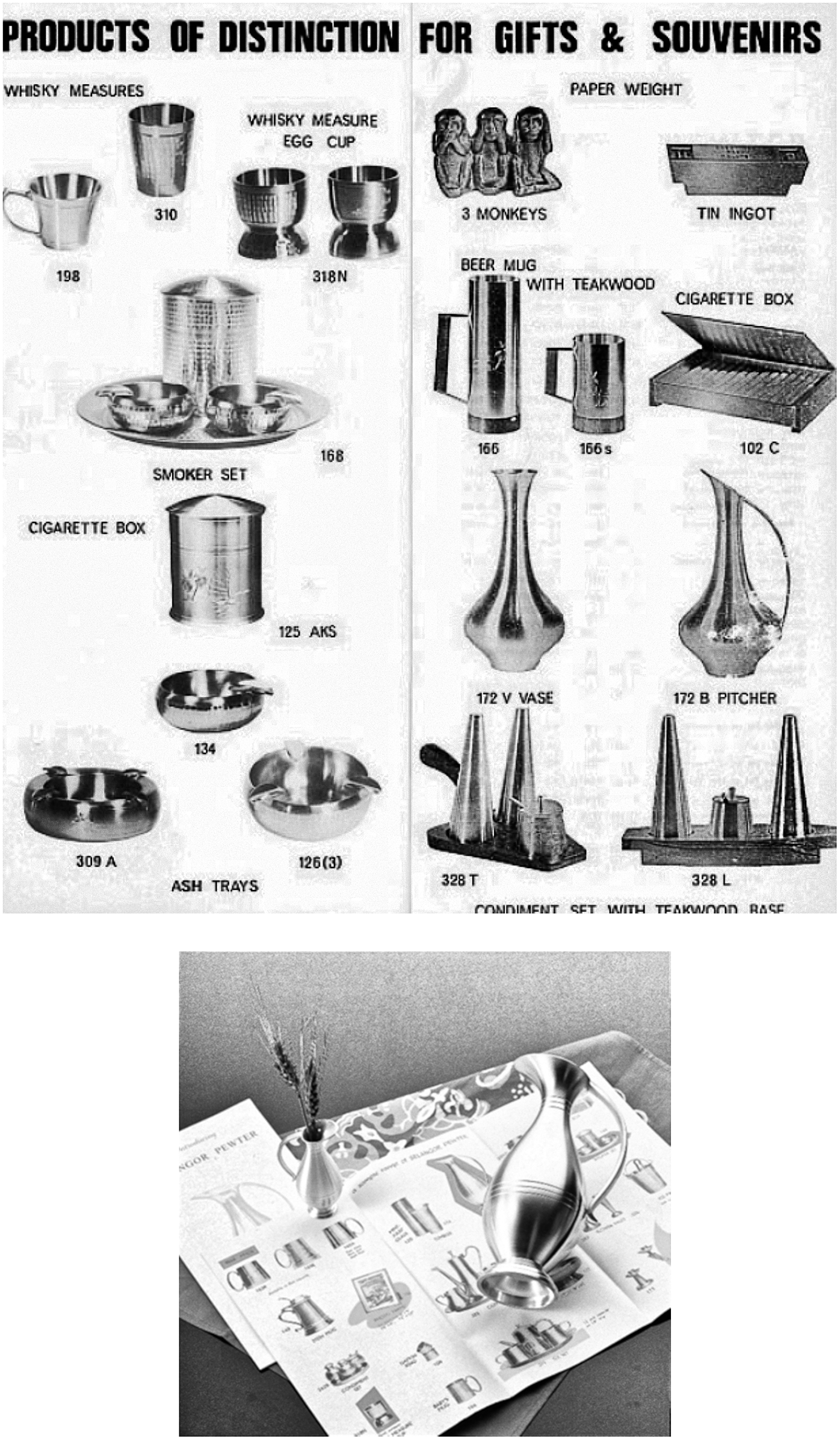

At that time, Selangor Pewter was heavily dependent on sales channels comprising agents and distributors at gift shops and department stores. A key problem that Selangor Pewter faced was that some rival pewter companies were copying its best-selling products and producing knockoff versions. When these products were put next to the ones produced by Selangor Pewter, there was little differentiation between the two appearance-wise, resulting in some customers purchasing the rivals’ products, as they were priced lower, albeit of poorer quality (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. A product advertisement from one of Selangor Pewter’s rivals.

Source: “Advertisements,” New Nation, December 26, 1976, 26. Used with permission.

Advertisements on the Straits Times—the leading English language newspaper in Singapore and Malaysia—on unauthorized copying of Selangor’s designs were largely ineffective (see Figure 8). A longer-term branding strategy was needed to set the company apart from newer rival pewter companies that had little grounding in design and technique and were attempting to ride the coattails of Selangor Pewter’s success. Emphasizing the business’s longevity and legacy highlighted a key asset that rival pewter companies did not have.

Figure 8. One of several advertisements that Selangor Pewter placed from 1975 to 1979 warning against unauthorized copying of its pewter designs.

Source: “Advertisements,” Straits Times, October 22, 1979, 26. Used with permission.

By externalizing the company’s consciousness of its own family and business history into a successful marketing tool, Selangor Pewter began acquiring legitimacy in guiding consumer taste in home décor and as the primary source of authenticity and originality.Footnote 63 The company’s active engagement with historical artifacts pivoted on its interests in showcasing the historicity of pewter through the lens of its own company history. To extend the narrative of Koon Seong’s legacy of the pewter business set up in 1885, Quistgaard proposed an exhibition of antique pewter pieces—including those made by Koon Seong—at cultural institutions in conjunction with the company’s centennial celebrations in 1985. An exhibition titled 100 Years of Pewter was held at Muzium Negara, the National Museum in Kuala Lumpur, followed by the National Museum Art Gallery in Singapore—with most of the pewter items sourced from the company’s collection of its products over the years.Footnote 64 The wider context of the exhibitions was to demonstrate the relationship between pewter and the Chinese migrant culture in the region at the turn of the twentieth century, essentially the narrative of Selangor Pewter itself. The exhibitions elevated the company’s status to that of being the living history of pewter in Southeast Asia, legitimizing the company’s status as the leader and pioneer in pewter manufacturing, a title to which no rival could lay claim.

Throughout his employment at Selangor Pewter, Quistgaard designed exclusively for the company, advised the company on technical aspects of product design, and represented the company at major fairs as well as in negotiations for and the establishment of offices in Tokyo and Copenhagen.Footnote 65 Quistgaard acted beyond his capacity as designer, blurring the boundaries between entrepreneurship and design for the company, and attempted to incorporate the “design mindset” in the company’s entire value chain. Quistgaard also had the implicit approval of the family to do so, because he too was part of the family through marriage to Boon Lay. The couple left Selangor Pewter in 1987 and returned to Denmark, but by then had created a foundational legacy whereby design gradually became a philosophy of the company. By the mid-1980s, the company had socialized its historical narrative both internally and externally, and using that narrative, Selangor Pewter sought opportunities to legitimize the narrative and image it constructed through collaborations with international designers.Footnote 66

Brand and Corporate Image Status Change Through a Royal Warrant

The concept of business longevity exhibited by Chinese entrepreneurs had to be reconstructed to adapt to a dynamic shift in Malaysia’s industrialization policies and contestations on the loyalty of Malaysian Chinese to the nation. The ability to do so came through a royal status granted to Selangor Pewter in 1979, which indirectly helped safeguard the company’s ownership and ward off control from outsiders and shaped the family business’s image as one tied to nationality rather than ethnicity.Footnote 67 Malaya was a colony with a multiethnic society, following the massive inflows of migrant labor from India and China who were systematically brought in by the colonists.Footnote 68 The road map to the colony’s independence was constructed through social bargaining that did not always sit well with the bumiputera Footnote 69—a political and economic reference to the majority Malay population of Malaya in the postcolonial era—and the local Chinese community—whose interests were represented by business elites during the late colonial era. The fragile social fabric unraveled on May 13, 1969, in the country’s worst racial clash, which occurred in Kuala Lumpur and left 196, mostly Chinese, dead.Footnote 70

There has never been an admission by the company, but by actively elevating its status into an internationally known brand, it was able to gradually distance itself from its Chinese family business identity. While it did not deliberately whitewash its identity, its growing presence in the Australian market contributed to the company’s ability to shift public perception from focusing on the managers’ ethnicity to the company’s national identity and international brand status. In 1978, while visiting a David Jones store in Perth, Australia, a salesperson had approached the sultan of Selangor, Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah, and told him that she knew the name “Selangor” because of the pewter company. The sultan was apparently so amused that his home state was made well known by Selangor Pewter that he related the story to Poh Kon during a factory visit and decided to bestow the company with the status of royal pewterer. The royal warrant was conferred in 1979, whereby every piece of pewter that the sultan bought from the company thereafter had the words engraved: “By royal appointment to his Royal Highness, the Sultan of Selangor,” a practice that mimicked businesses with royal warrants in Britain.Footnote 71 The only other known royal status granted was to P. H. Hendry in the 1920s, a jewelry business set up in 1902 by a Sinhalese diaspora entrepreneur of the same name in Kuala Lumpur.Footnote 72

To commemorate Selangor Pewter’s royal status, Quistgaard designed the Royal Collection (later renamed the Sovereign Collection), a tea set made of pewter with a mirror-like satin finish that gave the collection the appearance of polished silver and was an interpretation of the “Queen Anne style”—a popular architectural design in nineteenth-century America that later permeated furniture and tableware design (see Figure 9).Footnote 73

Figure 9. The Royal/Sovereign Collection tea service set designed by Quistgaard in 1981.

Source: Selangor Pewter Company Archives, Copenhagen. Used with permission.

Earlier, the company’s commitment to Malaysia was illustrated by the setup of Selberan—Selangor Pewter’s joint venture in gold and silver jewelry manufacturing with two European master jewelers in 1973. The company required the European craftsmen to stay in Malaysia indefinitely and to bring an additional two craftsmen from Switzerland to train the company’s craftspeople for three years.Footnote 74 With the royal patronage of a Malay sultan, the company held the status of a Malaysian company manufacturing high-quality products that were made locally. The royal warrant, together with a growth in exports and commitment to contribute to manufacturing in Malaysia, gave the company a lot more ground for stalling compliance with the Industrial Coordination Act 1975, under which all manufacturers would only be granted an operating license upon meeting government requirements, the most controversial one being the required allocation of 30 percent share capital to bumiputera investors if a company’s paid capital exceeded RM500,000.Footnote 75 Poh Kon and other entrepreneurs kept lobbying for the removal of the 30 percent equity allocation requirement, which was deemed unfriendly to business until it was finally scrapped in 2009.Footnote 76 Being privately held, the company also escaped much of the scrutiny by economists and the media directed toward Chinese business groups whose capital had grown from the increasing corporatization movement from the 1980s and their linkages with patronage relations with the state, some of which were criticized for producing an “ersatz capitalism” in Southeast Asia.Footnote 77

Selangor Pewter managers decided the company needed a name change to reflect the elevated status of both its national and international identities. Discussions of a name change to reflect the company’s internationalization had begun in the 1980s, but a consensus among family members could not be reached, there being concerns that the company could lose the trademarks it held and the reputation it had built up for decades with the name change.Footnote 78 Finally, in 1992, the family renamed the company Royal Selangor International (see Figure 10) to reflect not only an international identity but also its diversification into gold and silver jewelry, through its subsidiary Selberan, and acquisitions of two historically rich British pewter and silversmith companies.Footnote 79

Figure 10. The company logo designed in 1976 (left) and after the change of name in 1992 (right).

Source: Royal Selangor Company Archives. Used with permission.

Royal Selangor would be the only Malaysian company to have such a name, as the Malaysian government has prohibited company names from reflecting connections with royalty since 1997.Footnote 80

The new name was a combination of the royal warrant it received in 1979 and the Selangor state, which was once one of the two largest tin-rich regions in Malaya and was a significant contributor to the colony’s status as the world’s largest producer of tin. Selangor Pewter managers capitalized on the royal status—which they learned about from companies with British royal warrants—as a mark of recognition of excellence, as outlined by Britain’s Royal Warrant Holders Association.Footnote 81

Poh Kon reflected:

In the department store environment overseas, we were placed in the silver department, (which is) also always quite close to the china and glass departments. If you look around, you will see Royal Doulton, Royal Copenhagen, and they are all fine, premium products. And so, when we see ourselves there, we are in the same category of fine dining, fine giftware and home décor items. It came from thinking about how we position ourselves in the overseas environment.Footnote 82

Adding the word “Royal” to its brand name instantly attached prestige to the company and paid homage to its origins, while preventing confusion among its customers by allowing them to continue referring to its products as a “Selangor mug” or a “Selangor.”Footnote 83 The company saw that it was no longer competing in just one industry, but across industries in gifts, jewelry, flatware, and interior design that utilized various materials such as silver, ceramics, and glass. The new company name thus reflected not just a change in the organizational identity but also its readiness to compete among bigger brands across the globe.

Status-building and Market Recategorization in Pewter for British Expansion

New challenges arose when Selangor Pewter decided to enter the British market via an acquisition in London’s last cast pewter company, Englefields, in 1987. Englefields, founded in 1700, had a clientele that included Florence Nightingale and St. Paul’s Cathedral and a distributorship contract with high-end department store Harrods that Selangor Pewter could not tap into. The Malaysian company had to seek its own sales channels in Britain and thus needed a product differentiation strategy to distinguish it from British pewterers that already had a long-standing legacy with traditional tankard designs. Taking its cue from the use of its history that Quistgaard had established, Selangor Pewter approached renowned British cultural institutions. The company was initially more interested in reproducing antique silver tableware of the stately homes that had vast collections of silverware with intricate designs. It sent marketing proposals to homes of various British nobility, as well as the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum. The V&A Museum had newly created sales channels through souvenir and gift shops within its premises (the V&A Enterprise) intended to publicize its collections through sales of gifts and souvenirs, and plug the financial gap resulting from rising operating costs.Footnote 84 A contact with the V&A Enterprise was made through Vicki Thomas, a young designer-consultant who was initially hired by Englefields to research new pewter product lines that would appeal to younger buyers.

In the initial discussions with the V&A Enterprise, Selangor Pewter wanted to borrow some items from the museum and use the V&A logo so that the final products would be “authentic reproductions of pieces from the V&A Museum.”Footnote 85 These products were for markets in Australia, Britain, Canada, and New Zealand and carried a retail price between US$800 and US$1400.Footnote 86 The retail prices were a significant markup from the pewter range produced by Englefields, whose products were priced under £230 in 1983 (around US$350 based on historical exchange rates).Footnote 87 In return, the museum would get 10 percent of the ex-factory price of every item sold from the collection. Selangor Pewter was adamant that the designs had to be authenticated and was willing to pay a one-time professional fee to the V&A curators to obtain the certification.Footnote 88 This way, the company could tap into the prestige attached to the British silverware designs and institutions, something that affluent consumers were already familiar with.

Silver, with its white brilliance and lustrous appearance, was at its height of popularity in Britain in the late 1980s, as demonstrated by the prominence of British-based Ratners, which became the world’s second-largest retail jeweler in 1991.Footnote 89 While the high acceptance of silver as a decorative metal appeared to Selangor Pewter as a much easier entry point into the British market than pewter, the company did not give up altogether on marketing pewter products in Britain. Thomas and her colleague Irene Lamont—a ceramics and jewelry designer—had suggested that Englefields create a new line of pewter christening gifts such as egg cups and spoons, photo frames, and decorative plaques as commemorative gifts, targeting women as the main buyers of this product line.Footnote 90 That idea was passed over to Selangor Pewter to test the British market instead. The seminal theory of Mauss on gift-giving is that every gift is attached with a social obligation to reciprocate and thus perpetuates the gift and, to a larger extent, the retail economy.Footnote 91 The social nature of gift-giving means that the value of a gift interpreted not so much on the costs of production and price, but on the message the gift conveys, giving entrepreneurs and designers the creative power to manipulate the meanings of objects by recategorizing their use to reach a wider audience.Footnote 92 Christening gifts became an ideal cultural site for Selangor Pewter to produce and market an everlasting keepsake that follows the development and growth of a child—an idea of permanence not unlike receiving a De Beers diamond, which the jewelry company had marketed as “forever.”Footnote 93

In 1988, Selangor Pewter finalized its decision to create the Teddy Bears’ Picnic–themed collection of photo frames, cutlery, tooth boxes, and egg cups with adorable-looking bears sculptured in pewter. The designs were illustrated by Roy Simpson, a sculptor-designer and Thomas’s work contact (see Figure 11).Footnote 94

Figure 11. An example of a sketch of a cutlery set for babies by designer Roy Simpson for the Teddy Bears’ Picnic line.

Source: Selangor Pewter Company Archives, London. Used with permission.

The collection was based on a children’s song written in 1907, as the song title was license-free.Footnote 95 Sculptures of teddy bears in pewter were a deliberate choice to make the designs gender-neutral.Footnote 96 Teddy bears were also ideal as a branding image, as they were generic characters and were not copyrighted, yet shared an association with more famous, copyrighted characters such as Winnie-the-Pooh. It was a win-win solution from the perspective of design and economics. The Teddy Bears’ Picnic collection broke new ground, as pewter was no longer confined only as traditional designs and gifts for men but also for children. However, this could only be achieved by a non-British company that was free from the rigidity imposed by guilds and charters that dictate the method and design of pewterware and that the British market has been synonymous with for centuries.

Nevertheless, as christening gifts had been mostly made of silver—an invented tradition since the Tudor period—there was no guarantee that the market would readily accept pewter as a metal precious enough to be turned into gifts for babies.Footnote 97 The combined forces of the growing presence of souvenir and gift shops at British museums and galleries from 1990 and Gerald Ratner’s infamous speech made in 1991 about silver being “total crap” gave pewter more space to be reinvented as a historically rich and precious metal.Footnote 98 The backlash against Ratners’ silver products was most evident when its Christmas sales in 1991 slumped 15 percent at a time when the jewelry market alone would usually rake in 40 percent of its total annual sales.Footnote 99 Meanwhile, the Teddy Bears’ Picnic collection—launched at the Birmingham Fair in 1989—has become one of the company’s most popular ranges today and remains so today.Footnote 100

Despite Selangor Pewter breaking into the British market, the V&A Enterprise explicitly told the management that it would prefer to have an Englefields V&A Range and that the pewter collection be produced in Britain instead of Malaysia.Footnote 101 Selangor Pewter could have complied with the V&A’s request to speed up the partnership agreement, but it insisted that the manufacturing processes be kept in Malaysia, while development and quality control could be done in Britain.Footnote 102 The Pewterer’s Hall, where the old Englefields’ touchmark was registered, was also unhappy that Selangor Pewter wanted to stamp the V&A range with the Englefields’ touchmark, despite production being in Malaysia.Footnote 103 It underscored how British institutions remained protective of the “Britishness” of pewter as its arbiter of quality, despite the Malaysian company’s longevity and reputation in other markets, and demonstrated Selangor Pewter’s conscious efforts to keep its national identity. Nevertheless, the company managed to keep discussions with the V&A ongoing for another seven years and became the V&A Enterprise’s first licensee partner in Asia, whereby the British cultural institution launched the first V&A range using the Royal Selangor brand name, with international distributorship starting from 1996.Footnote 104 By then, whether Royal Selangor was British enough no longer mattered. The Malaysian company had deep international sales channels through its flagship stores, which Englefields did not—an increasingly important criterion for the V&A Enterprise, given that 60 percent of its products were sold outside Britain.

Conclusion

The case study of Royal Selangor’s international branding strategies shows how designs and historical narratives were utilized to renegotiate the meaning of national identity in the postcolonial context. In a multicultural postcolonial society and during a period when national identities were being redefined, Royal Selangor capitalized on the identity of its former colonizer to overcome initial difficulties of marketing locally manufactured products for export in Western markets and used its international identity to forge a national one. The company’s mobilization of resources in design and narratives, on one hand, elevated the company’s competitiveness in the international gifts sector, and on the other, gave the company flexibility to adapt to shifting ideas of national identities in the postcolonial era.

Historical studies on former colonies have often positioned nationalism as a reaction against colonialism and emphasized the key roles of state actors in propagating nationalistic ideologies through official and linear narratives. However, this case study shows that businesses also have agency in renarrating colonial legacies to their advantage and contributes to the idea of nation-building by diverging from the textbook prescription of postcolonial economic development. Royal Selangor redefined the crafts industry and reimagined the idea of pewter—which was intrinsically tied to the legacy of Malaysia’s former colonizer Britain—into a Made in Malaysia brand that is prestigious-looking, high quality, and comparable with the Western standards of design and craftmanship.

This business evolved through a cosmopolitan malleability that stemmed from the company managers’ openness to ideas and hybrid cultures learned from colonial experiences, which enabled the company to turn Eurocentrism on its head. The case of Royal Selangor deviates from the mainstream narratives on Chinese businesses in Southeast Asia, which have often been studied through network and political economy theoretical frameworks. This study thus opens new research agendas for scholars and historians interested in utilizing a multidisciplinary approach in business history, organizational studies, and nationalism to reframe the current understanding of businesses in the former colonies of Southeast Asia and analyze the historical processes of branding and entrepreneurship. By doing so, researchers can cast new light on the complex processes involved in creating economic change in developing countries, many of which also have colonial histories. In future research, more consideration could be given to historical analyses of companies in various sectors, geographies, and institutional environments to refine existing theoretical frameworks on global branding.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank several individuals and institutions for their generous support in the preparation of this article. The Sato Yo International Scholarship Foundation provided financial support without which this project would have been unattainable. Tan Sri Yong Poh Kon, of Royal Selangor (RS), provided access to the company’s archives and insights into the company’s history. RS directors Sun Mun Ha née Yong and Yong Poh Shin also offered insights into the company’s past management processes, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. Lim Bee Vian of the Malaysian Industrial Development Authority provided access to the company’s archival sources stored on government premises. Guay Boon Lay provided vivid details of pewter design and the creative processes in the company’s design department. Vicki Thomas offered various documents and sketches of the company’s pewter designs and insights on research in gift manufacturing. Three anonymous referees provided invaluable comments that have greatly improved this article. My thesis advisers Takafumi Kurosawa and Steven Ivings, as well as Tao Wang and Ai Hisano, provided constructive feedback for this article. All mistakes and omissions remain the author’s responsibility.