Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria belonging to the order Chlamydiales [Reference Corsaro and Greub1]. Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common bacterial cause of sexually transmitted infections worldwide [Reference Baud and Greub2]. In women, 90% of C. trachomatis infections remain asymptomatic. However, if left untreated, chlamydial infection can lead to scarring of uterine tubes, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy (EP) and adverse pregnancy outcomes [Reference Baud and Greub2, Reference Darville and Hiltke3]. C. trachomatis induced pathogenesis is largely a result of chronic immunopathological reactions, most likely caused by persistent infections [Reference Darville and Hiltke3].

Waddlia chondrophila, a Chlamydia-related bacterium, has recently been associated with both animal and human adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as miscarriage [Reference Baud and Greub2, Reference Baud4–Reference Baud6]. Its mode of transmission and pathogenesis remains to be explored.

Since several Chlamydia spp. and Chlamydia-related bacteria colonize the cervico-vaginal mucosa [Reference Baud5–Reference Baud7], which may lead to tubal scarring and have been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in humans, we thus investigated their role in EPs. EP, a condition in which a fertilized egg settles and grows in a location other than the inner lining of the uterus, occurs in 2% of all pregnancies and remains the leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the first trimester of gestation [Reference Rana8, Reference Farquhar9].

A total of 343 patients were recruited at Tu Du Hospital, Hô Chi Minh City (Vietnam). The EP group included 177 women with an EP treated by laparoscopic salpingectomy. The control group included 166 women without any history of previous EP and who experienced an uneventful pregnancy. Blood samples, fallopian tubes or placental biopsies were collected for each EP and control patient. Local ethical committees of both hospitals (clinical part in Vietnam and experimental part in Switzerland) approved the study protocol and all patients included in the study gave their written consent.

Serological status and epidemiological data were compared between patients with and without EPs, or between patients with and without Waddlia-positive serology by Pearson's χ 2 test (or Fisher's exact test when indicated) for categorical variables. For continuous variables, medians were compared by the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. Multivariate logistic regressions were performed to identify factors independently associated with EPs and miscarriages. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata v. 13.0 (StataCorp., USA).

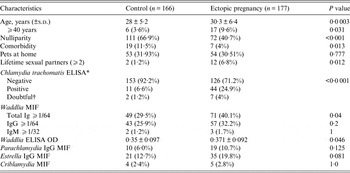

Sociodemographical data are presented in Table 1. All sera were tested for antibodies against C. trachomatis (Table 1), as described previously [Reference Corsaro and Greub1, Reference Baud4, Reference Baud6, Reference Baud7, Reference Baud10, Reference Baud, Regan and Greub11]. C. trachomatis IgG seroprevalence was 6·6% in the present Asian control population. Similar prevalence has been described by other studies [Reference Baud7, Reference Shaw and Horne12, Reference Yongjun13]. C. trachomatis seroprevalence was higher for women who experienced an EP (24·9%) than for women with an uneventful pregnancy (6·6%, P < 0·001).

Table 1. Sociodemographical data and serologies according to pregnancy outcome

MIF, Microimmunofluorescence; OD, optical density.

* MOMP-R, CT pELISA (R-Biopharm, Germany)

† Similar P values when doubtful were excluded.

For Waddlia and other Chlamydia-related bacteria microimmunofluorescence (MIF) tests were performed as described previously [Reference Corsaro and Greub1, Reference Baud4, Reference Baud6]. All immunofluorescence samples were read by two independent observers and only congruent results were considered positive. Sera that exhibited total immunoglobulin (Ig) titre ⩾1:64 were tested for IgG and IgM reactivity using corresponding anti-human Fluorescein-labelled Ig (FluolineG or FluolineM, bioMérieux, France) and serial twofold dilutions of sera. Waddlia IgG and IgM positivity cut-offs were ⩾1:64 and ⩾1:32, respectively [Reference Corsaro and Greub1]. There was a significant association between total anti-Waddlia antibodies detected by MIF and EP (P = 0·04). However, there was no statistical association with EP when anti-Waddlia IgG, or anti-Waddlia IgM, were considered. Waddlia ELISA was performed as described previously [Reference Lienard14] and confirmed the association between Waddlia seropositivity and EP (P = 0·046). Serological evidence of human exposure to other Chlamydia-related bacteria, such as Parachlamydia acanthamoebae, Estrella lausannensis and Criblamydia sequanensis were not associated with EP (Table 1). When all variables from Table 1 were considered (stepwise logistic regression analysis), the only three independent factors associated with EP were a positive C. trachomatis serology [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 5·41, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2·58–11·31], number of sexual partners (aOR 9·34, 95% CI 1·95–44·66) and parity (aOR 2·69, 95% CI 1·94–3·75), which are well known risk factors for EP [Reference Rana8, Reference Farquhar9]. Patients' characteristics according to their C. trachomatis serological status are given in Supplementary Table S1.

Women seropositive for Waddlia (n = 100, 29·2%) were older (P = 0·007) and experienced previous miscarriages more frequently (P = 0·005) than Waddlia-negative women (Table 2). The association between Waddlia seropositivity and miscarriage remained significant (aOR 1·87, 95% CI 1·02–3·42) even after adjustment for age, parity, comorbidity and other serologies including C. trachomatis. There was no statistical association between Waddlia-positive serology and medical comorbidities, gynaecological complaints during pregnancy, work status, number of lifetime sexual partners or presence of pets at home.

Table 2. Patient`s characteristics according to their Waddlia serological status

MIF, Microimmunofluorescence.

There was no cross-reaction between Waddlia and C. trachomatis serologies, since 77 patients (23·1%) were positive only for Waddlia IgG and 37 (11·1%) were positive only for C. trachomatis IgG (Table 2). Only 18 patient (5·4%) were positive for both bacteria (P = 0·513).

Presence of Waddlia [Reference Goy15, Reference Lienard16] and/or C. trachomatis [Reference Baud7] DNA was tested in IgG-positive patients. DNA extraction was performed from a 2-cm piece of fallopian tube (EP) or placental (C) tissue using Wizard SV genomic DNA purification kit (Promega Corporation, USA), and a pan-Chlamydiales PCR was performed as described previously [Reference Croxatto17]. This Pan-Chlamydiales PCR is able to detect up to five DNA copies per reaction and demonstrated similar performance compared to specific Chlamydiales PCRs. Neither the 50 fallopian tubes nor the 43 placental samples with a positive Waddlia and/or C. trachomatis serology were positive for Waddlia or C. trachomatis DNA. All 20 control patients with a negative serology (10 from the ‘EP' group and 10 from the ‘C’ group) were also negative by PCR.

In summary, our data showed a strong association between C. trachomatis seropositivity and EP. However, neither the fallopian tubes nor placenta of women with positive Chlamydia or Waddlia serologies demonstrated presence of respective bacteria, which has also been shown by others [Reference Shaw and Horne12]. Moreover, IgG but not IgM antibodies were detected during EPs. Thus, these results suggest that the persistence of the bacteria is not necessary to induce tubal damage, and reinforces the role of an immunopathological process due to a previous chlamydial infection [Reference Witkin and Ledger18, Reference Baud, Regan and Greub19]. However, the physiopathology mechanism by which tubal scarring occurs without the presence of bacteria is not yet fully understood [Reference Shaw and Horne12, Reference Baud, Regan and Greub19].

Waddlia IgG seroprevalence in the control group (25·9%) was higher than previously described in other asymptomatic patients: 14·6% in Switzerland [Reference Baud6], and 7·1% in London [Reference Baud4]. This difference could be explained as a result of higher genetic susceptibility of the Vietnamese population to Waddlia infection or greater exposure to the yet unknown source of Waddlia infection [Reference Baud and Greub2, Reference Baud4, Reference Baud6].

Whereas our study only identified a limited association of Waddlia with EP (P = 0·04), we observed a strong correlation between previous history of miscarriage and positive Waddlia serology (P = 0·005). This was expected since Waddlia was previously reported as an abortigenic agent in both animal and human populations [Reference Baud and Greub2, Reference Baud4–Reference Baud6, Reference Baud, Regan and Greub19].

A major limitation of the study was the absence of data concerning other potential confounding factors for EP (i.e. other infectious agents) and miscarriage (i.e. chromosomal anomalies).

In conclusion, this study confirmed the serological association of C. trachomatis with EP [Reference Rana8] and of Waddlia with miscarriage [Reference Baud4, Reference Baud6]. Moreover, we showed an association between anti-Waddlia antibodies and EP using both immunofluorescence and ELISA. Absence of C. trachomatis and W. chondrophila DNA in the fallopian tubes or placental tissues suggests that immunopathological mechanisms rather than bacterial infection are involved in EP. Further investigations are needed to understand the high prevalence of Waddlia in this Asian population and to precise its role in EP.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0950268814003616.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the midwives and doctors who actively participated in this study at Tu Du Hospital. Their involvement was essential to the whole process, and they enthusiastically gave their time to provide information and samples.

This work was supported by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Maternity, Lausanne, Switzerland. This work was also partially funded by SNSF grant no. 310 030– 130 466 attributed to Professor G. Greub. David Baud is supported by the ‘Fondation Leenaards’ through the ‘Bourse pour la relève académique’.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.