Introduction

Background

Self-harm and suicide pose serious public health concerns, with suicide accounting for at least 700,000 deaths per year globally and previous self-harm (intentional self-injury or poisoning regardless of suicidal intent) or ideation (thoughts of suicide-related behaviour) both being strong predictors of death by suicide (Knipe et al., Reference Knipe, Padmanathan, Newton-Howes, Chan and Kapur2022; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Murphy, O’Hagan, Maguire and O’Reilly2023a, Reference Ross, O’Reilly, O’Hagan and Maguire2023b). The targeted reduction of self-harm as a key precursor to death by suicide is central to national suicide prevention strategies (Department of Health, 2019). Self-harm and ideation represent a substantial number of all hospital emergency department (ED) visits (Clements et al., Reference Clements, Turnbull, Hawton, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Townsend, Khundakar and Kapur2016), therefore EDs present a key entry point for intervention and prevention (Bird et al., Reference Bird, Lago, Eagar and Pai2021). Rates of hospital presenting self-harm and ideation are increasing, especially in adolescents and young adults (Bommersbach et al., Reference Bommersbach, Mckean, Olfson and Rhee2023; Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, McMahon, McNicholas, Corcoran, Perry and Arensman2018; Stapelberg et al., Reference Stapelberg, Sveticic, Hughes and Turner2020). However, little is known on how risk is patterned by childhood contact with social services.

Existing evidence

Children in contact with social services (i.e. children subject to a referral, in-home child protection/family support measures or out-of-home care) are at increased risk of a range of adverse outcomes given their exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Exposure to maltreatment, poverty, family dysfunction and parental mental ill-health or substance misuse are well-established risk factors for self-harm and suicidal ideation (hereafter ideation) (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Saunders and O’Connor2012; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Scott, Bhutta, Harris, Danese and Samara2020). Research suggests that the prevalence of self-harm and ideation is disproportionately high in children known to social services (Leckning et al., Reference Leckning, He, Condon, Hirvonen, Milroy and Guthridge2021; O’Hare et al., Reference O’Hare, Watkeys, Dean, Tzoumakis, Whitten, Harris, Laurens, Carr and Green2023), particularly those placed in out-of-home care (also described as public or state care, or being looked after, hereafter ‘care’) (Allik et al., Reference Allik, Brown, Gedeon, Leyland and Henderson2022; Evans et al., Reference Evans, White, Turley, Slater, Morgan, Strange and Scourfield2017; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, McLay, Clark, King, MacKay, Minnis and Pell2021; McKenna et al., Reference McKenna, O’Reilly and Maguire2023a). Childhood disadvantage can persist into adulthood and contact with social services is associated with a range of adverse health and social outcomes in adulthood (McKenna et al., Reference McKenna, O’Reilly and Maguire2023b; Sariaslan et al., Reference Sariaslan, Kääriälä, Pitkänen, Remes, Aaltonen, Hiilamo, Martikainen and Fazel2022; Xie et al., Reference Xie, De Mestral and Batty2021). However, the association between childhood contact with social services and self-harm and ideation in adulthood has yet to be robustly explored (McKenna et al., Reference McKenna, Donnelly, Onyeka, O’Reilly and Maguire2021).

The majority of prior research is limited by small sample sizes (Courtney et al., Reference Courtney, Dworsky, Brown, Cary, Love and Vorhies2011; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Wade, Byford, Weatherly and Lee2006; Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Taylor, Killick and Bickerstaff2015; Vinnerljung et al., Reference Vinnerljung, Sundell, Lölfholm and Humlesjö2006b) and cross-sectional studies that utilise retrospective recall of childhood contact with social services (Afifi et al., Reference Afifi, McTavish, Turner, MacMillan and Wathen2018; Gentil et al., Reference Gentil, Grenier and Fleury2021; Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, Moniruzzaman and Somers2015; Roos et al., Reference Roos, Distasio, Bolton, Katz, Afifi, Isaak, Goering, Bruce and Sareen2014). To date, the evidence base from large-scale prospective studies is restricted to hospitalised suicide attempt, with studies in Sweden showing elevated risk in adults with a childhood history of care or receipt of child welfare services at home (Almquist et al., Reference Almquist, Rojas, Vinnerljung and Brännström2020; Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Vinnerljung and Hjern2011; Vinnerljung et al., Reference Vinnerljung, Brännström and Hjern2015, Reference Vinnerljung, Hjern and Lindblad2006a). There is a need for population-wide longitudinal cohort studies that can quantify the association between receipt of children’s social care services and ED-presenting self-harm and ideation in young adulthood. Furthermore, high thresholds for intervention from statutory social services mean a large proportion of referrals do not result in any service provision (Bunting et al., Reference Bunting, McCartan, McGhee, Bywaters, Daniel, Featherstone and Slater2018; UK Government, 2024). Existing research shows individuals referred to social services but assessed as not in need of any help or protection are at increased risk of mental ill-health and death by suicide (McKenna et al., Reference McKenna, O’Reilly and Maguire2023a, Reference McKenna, O’Reilly and Maguire2023b). Consequently, the aim of this study is to quantify the association between all tiers of contact with children’s social services, including those assessed as not in need, and ED-presenting self-harm and ideation in young adulthood using longitudinal, population-wide linked administrative and health data sources.

Methods

Patient and public involvement statement

This study is part of a programme of research being produced in partnership with the charity Voice of Young People in Care (VOYPIC) and the Data Research Advisory Group comprised of lived experience experts (care experienced young people) who meet quarterly with the research team to assist with the development of research questions, interpretation of results and dissemination of findings. The results reported in this paper were the focus of two participatory workshops which directly influenced reporting and dissemination in the following ways: (1) incorporation of the positive message that the majority of care experienced young adults do not present to ED with self-harm or ideation; (2) incorporation of the recommendation that care experienced individuals often require additional support; (3) the development of an easy-read summary of the study and infographics which will be promoted on social media post-publication of the peer-reviewed paper.

Study design

This retrospective cohort study linked several Northern Ireland (NI) population-wide databases: the National Health Applications and Infrastructure Services (NHAIS) database; the Social Services Client Administration and Retrieval Environment (SOSCARE) system; General Register Office (GRO) death records and the Northern Ireland Registry of Self-Harm (NIRSH). Publicly available area-level measures of rurality and deprivation were also included. Linkage was completed within the NI Trusted Research Environment’s Honest Broker Service (HBS) in collaboration with the Administrative Data Research Centre NI (ADRC NI) by matching of anonymised Health and Care Number (HCN), a unique identifier recorded in any interactions with health and social care services in NI. Extracted data maintained patient anonymity by HBS staff removing all identifiable data from the dataset prior to researcher access. All statistical outputs were subject to additional disclosure control measures, including restrictions on cell numbers to protect confidentiality. Reporting follows the Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (von Elm et al., Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2008).

The datasets

NHAIS contains demographic information on all individuals registered with a general practitioner (GP). NI offers free ‘at the point of service’ health and social care, ensuring almost universal registration within the population (Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency, 2016). The NHAIS cohort was all individuals alive and resident in NI during follow-up who were born between 1 January 1985 and 31 December 1993 (N = 328,694) and aged at least age 18 years in 2012, allowing for their entire childhood social care history to be captured from SOSCARE before outcome measurement from NIRSH began in 2012. Data on age, sex, area-level income deprivation and area of residence were derived from NHAIS. Area of residence and area-level income deprivation were assigned by the data custodians using patient address in 2010 from NHAIS. Area of residence was based on a classification of settlements in NI and grouped into urban (comprising the two largest cities), intermediate and rural (Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency, 2015). A measure of disadvantage was extracted from the income deprivation domain of the Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure (NIMDM), which provides information on the proportion of the population in each area living in households in receipt of income-related benefits and tax credits in 2010 (Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency, 2010), and coded into two groups (less deprived and more deprived). In the creation of this large, linked dataset, the data providers allowed for allocation of area-level measures at one time point only. Mortality data from the GRO were used to delineate the cohort denominator.

SOSCARE data from 1985 to 2015 were linked containing the case records of all individual interactions with children’s social services, which in NI are the responsibility of five regional Health and Social Care Trusts (HSCT). Childhood interaction with social services was classified into four mutually exclusive groups, based on highest level: (i) no contact, (ii) referred but assessed as not in need of help or protection, in every interaction with social services (NIN), (iii) child in need (CIN) (i.e. subject to a CIN plan or child protection measures in their own home) and (iv) child in care (CIC) (i.e. foster, kinship, residential care or placed with parent). Although the legal definition of a child in care in the UK is a ‘looked after child’, lived experience experts identified a strong preference for the term child in care. A child in care is by definition also a child in need but they are examined here as a separate group.

The NIRSH is a national surveillance system which records information on all presentations to EDs in NI for acts of self-harm or thoughts of suicide or self-harm, where no physical act has occurred (hereafter ‘ideation’) (Public Health Agency, 2018). Outcome measures comprised individual-level yes/no indicators for presentation to EDs at any point 2012–2015 for each presentation type: (1) self-harm; (2) ideation and (3) a composite indicator for any self-harm or ideation (i.e. individuals in this group may have presented with self-harm, or with ideation, or with both during the follow-up period). Self-harm and ideation outcomes were non-exclusive, therefore individuals with more than one type of presentation are counted in both standalone outcome groups. The composite indicator for any self-harm or ideation counted individuals only once.

Study cohort

The final cohort was N = 253,495 individuals in NI born 1985–1993 with full data (Fig. 1). The final cohort was aged 18–26 years in 2012 when the NIRSH data (outcome data) began and aged 22–30 years in 2015 when the NIRSH data ended. Individuals not registered with a GP (primarily due to emigration or death) and those who died during follow-up were excluded. Also excluded were individuals missing observations for sex, area-level factors and HSCT identifier to allow complete-case analysis, adjusting for the natural clustering of individuals by HSCT. Individuals recorded within social services data as having a disability were excluded to limit the possible confounding of social care contact and self-harm or ideation risk caused by existing disabilities.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the cohort evolution for the longitudinal analysis of self-harm and ideation in young adulthood based on level of childhood contact with social services.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to delineate cohort characteristics and the prevalence of self-harm and ideation. Outcomes and covariates were compared by social care subgroup using the chi-square statistic for categorical variables. Separate multilevel logistic regression models estimated the association between childhood contact with social services and self-harm and ideation in young adulthood accounting for age, sex, area of residence and deprivation, and the amount of variation attributable to clustering by HSCT. The data are inherently hierarchical, as individuals are naturally clustered within HSCT. Outcomes for two observations in the same cluster are often more alike than are outcomes for two observations from different clusters, even after accounting for individual characteristics. Multilevel modelling (MLM) is an advanced statistical technique for analysing clustered data which reduces the risk of bias resulting from within-cluster homogeneity compared to traditional regression methods.

Results

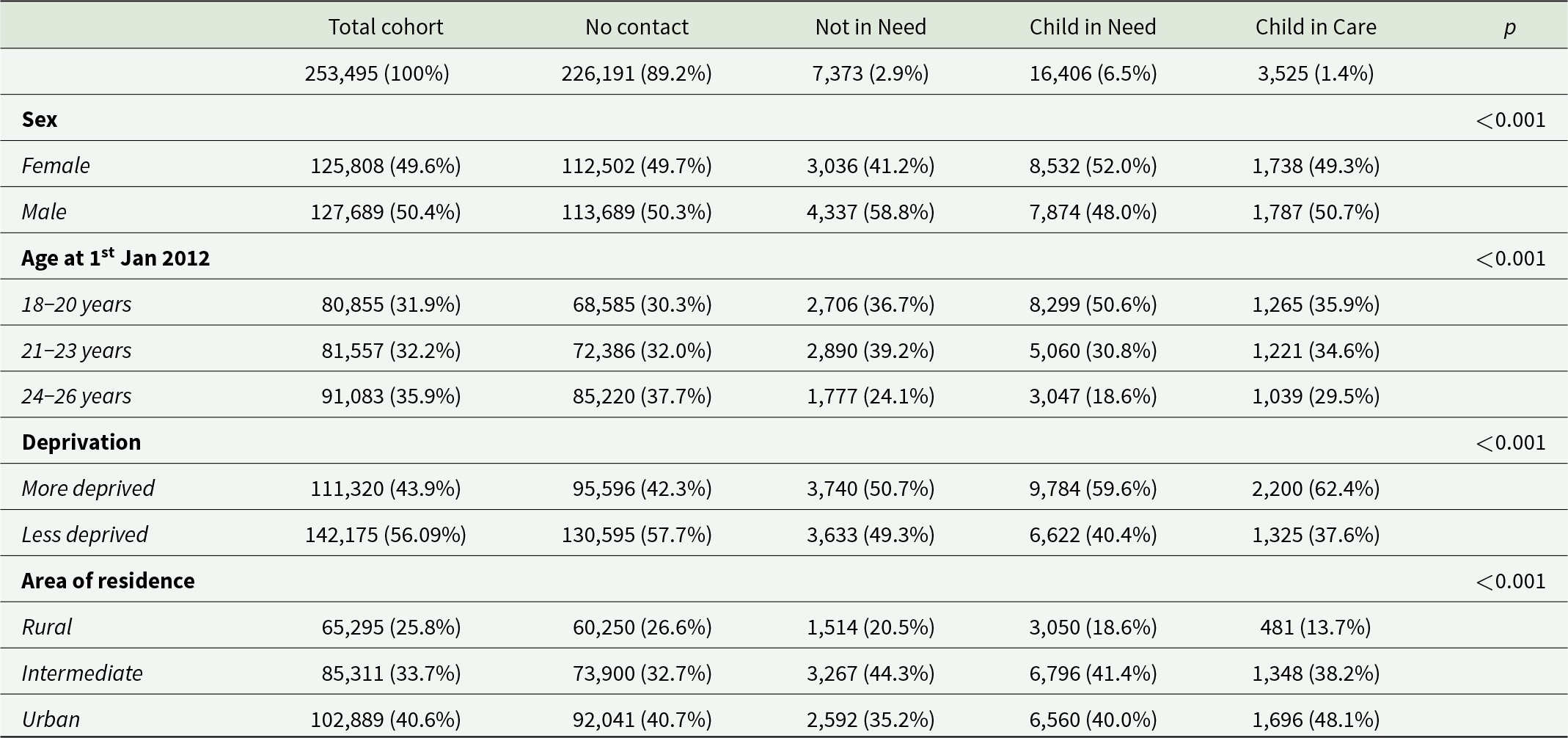

Of the cohort of N = 253,495 individuals born 1985–1993 and aged 18–26 years at the start of follow-up (1 January 2012), 27,304 (10.8%) had a childhood history of contact with social services (2.9% NIN, 6.5% CIN and 1.4% CIC (Table 1)). There was no substantial difference in sex distribution across categories except for those deemed NIN, which had a male majority (58.8%, p < 0.001). The age profile of the cohort varied according to level of social care contact. Among adults with no contact, 30.3% were aged 18–20 years, while over half (50.6%) of adults with a CIN history were in this youngest age category. Level of income deprivation increased with level of social services contact, with a higher proportion of adults known as a CIN and CIC during childhood living in areas with the greatest income deprivation (59.6% and 62.4% respectively). Young adults with a history of placement in care had a more deprived and urban profile than other subgroups.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the cohort by level of childhood contact with social services (N = 253,495)

Data are n (%).

p value from χ 2 tests for categorical variables.

Overall, 4,888 (1.9%) young adult cohort members presented to EDs with self-harm and/or ideation during follow-up (Table 2). While individuals with childhood social care contact comprised 10.8% of the cohort, they accounted for 40.9%* of young adults that presented with self-harm and/or ideation (Table 2, footnotes). Self-harm and ideation are not mutually exclusive: 4,026 (1.6%) young adult cohort members presented to EDs with self-harm whilst 1,669 (0.7%) presented with ideation (Table 2). The prevalence of self-harm and ideation increased stepwise with level of childhood social care contact. Proportionately, the prevalence of self-harm in care experienced young adults (CIC) was approximately 11 times that observed in those with no social care contact (11.2% vs 1.0%) and approximately 14 times for ideation (5.9% vs 0.4%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Likelihood of self-harm or ideation among young adults in Northern Ireland born 1985–1993 by level of childhood contact with social services (N = 253,495)

Data are number (%) of individuals presenting to ED within each social care category and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals from multilevel logistic regression models adjusted for clustering by Health and Social Care Trust.

a Adjusted for sex, age (years), area-level income deprivation, area of residence and clustering by HSCT.*Of n = 4888 individuals that presented with any self-harm or ideation n = 1,999 had contact with social services in childhood ((346 + 1,178 + 475)/4888*100 = 40.9%).

The graded relationship between the level of social services contact and self-harm or ideation is also evident in the multilevel regression analyses (Table 2). Likelihood increased stepwise with level of childhood social care contact with modest attenuation by adding covariates. Care experienced young adults were over 10 times more likely to present with self-harm (OR = 10.33 [95% CI, 9.22–11.58]) and over 13 times more likely to present with ideation (OR = 13.17 [95% CI, 11.26–15.41]) compared to young adults with no contact with social services in childhood. Young adults with a CIN history were over five times more likely to present with self-harm or with ideation (OR = 5.49 [95% CI, 5.08–5.94] and OR = 5.58 [95% CI, 4.94–6.31] respectively) compared to those with no contact with social services in childhood. Even young adults assessed as NIN in childhood were over three times more likely to present with self-harm (OR = 3.50 [95% CI, 3.09–3.98]) or ideation (OR = 3.65 [95% CI, 3.00–4.44]) than those with no contact with social services.

The significant Chi-squared test (MLM vs logistic) in models for likelihood of self-harm (χ 2 = 12.01, p < 0.001), ideation (χ 2 = 12.58, p < 0.001) and any self-harm or ideation (χ 2 = 12.39, p < 0.001) shows that the multilevel models are a better fit to the data than logistic models which do not account for HSCT variation. In fully adjusted models, the intraclass correlation estimated that Trust variation comprised just 0.2% of the total residual variance for self-harm presentations, 0.4% for ideation and 0.2% for any self-harm or ideation [full results available on request].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to capture population-wide, national surveillance data on presentations by young adults to EDs for self-harm or ideation, stratified by all tiers of childhood social care contact. It is the first to quantify that 40.9% of young adults (ranging from 18 to 30 years old) who present to EDs due to self-harm or ideation have at least some contact with social services in childhood. This study extends previous population-wide evidence of ED-presenting suicide attempt among adults with a history of in-home or out-of-home care (Almquist et al., Reference Almquist, Rojas, Vinnerljung and Brännström2020; Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Vinnerljung and Hjern2011; Vinnerljung et al., Reference Vinnerljung, Brännström and Hjern2015, Reference Vinnerljung, Hjern and Lindblad2006a) by including data on all self-harm acts, all ideation and all tiers of childhood contact with social services, including referrals that did not result in service provision. The highest risk is observed in care experienced young adults, who are 10 times more likely to present to an ED with self-harm and 13 times more likely to present with ideation compared to peers with no childhood contact. However, even those deemed not in need were over three times more likely to present with self-harm or ideation. The graded relationship may be indicative of confounding by indication, as level of social care intervention increases with the degree of potential harm to the child. There is a dose–response relationship between number and severity of ACEs and the incidence and persistence of mental health problems in adulthood (Bürgin et al., Reference Bürgin, Witt, Seker, D’Huart, Meier, Jenkel, Boonmann, Schmeck, Fegert and Schmid2023; Daníelsdóttir et al., Reference Daníelsdóttir, Aspelund, Shen, Halldorsdottir, Jakobsdóttir, Song, Lu, Kuja-Halkola, Larsson, Fall, Magnusson, Fang, Bergstedt and Valdimarsdóttir2024).

The large and disproportionate burden of self-harm and ideation in these young adults may be linked to influences before, during and after contact with social services. Children come to the attention of social services for a reason. Exposure to domestic violence and concerns about parental mental health are the most common factors recorded in social care assessments in the UK (UK Government, 2024), which tend to occur in clusters with other types of adversity such as poverty and maltreatment (Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022; Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Marteau, Fonagy and Abel2019). Children in care often experience barriers to accessing appropriate mental health support both during placement and after aging-out (Fargas-Malet and McSherry, Reference Fargas-Malet and McSherry2018; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Halligan, Denne, Hamilton‐Giachritsis, MacLeod, Wilkins and Hiller2023, Reference Phillips, Hiller, Halligan, Lavi, Macleod and Wilkins2024). Disadvantage can be reinforced or exacerbated across the life course, resulting in health, social and economic inequalities which are risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviour (Brännström et al., Reference Brännström, Vinnerljung, Forsman and Almquist2017).

While likelihood of self-harm or ideation is highest in care experienced young adults, these represent a comparatively small exposure group and three times as many adults with lower tiers of social care contact presented to EDs with self-harm or ideation. The significant overlap between childhood contact with social services and need for acute care for self-harm or suicidal crisis requires population-level strategies to reduce risk factors and evidence-based practices targeted at individuals. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for self-harm emphasises the need for a psychosocial assessment following any self-harm episode (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022) and liaison psychiatry teams have a crucial role delivering psychosocial assessment (Mughal et al., Reference Mughal, Burton, Fletcher, Lascelles, O’Connor, Rae, Thomson and Kapur2023). However, there is considerable variation in the management of self-harm in the ED setting (Arensman et al., Reference Arensman, Griffin, Daly, Corcoran, Cassidy and Perry2018) and there are currently no NICE guidelines covering the management of ideation. New models of care including a national clinical programme for the management of self-harm and suicidal ideation (NCPSHI) in hospital in Ireland (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Corcoran, Gunnell, Chang, McElroy, O’Connell, Arensman, Perry and Griffin2023; Health Service Executive Ireland, 2022) and the Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation 2 (ED-SAFE 2) cluster RCT (Boudreaux et al., Reference Boudreaux, Larkin, Vallejo Sefair, Ma, Li, Ibrahim, Zeger, Brown, Pelletier and Miller2023) demonstrate improved rates of psychosocial assessment and mental health referrals following discharge and reduced presentations for suicidal behaviour. While interventions should not be restricted to high-risk groups, clinical training and guidelines could assist clinicians to identify individuals at increased risk due to their social care history.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study was the use of longitudinal, population-wide administrative data that captured all tiers of childhood contact with social services, including those assessed as not in need. Outcome data were accessed via the only national surveillance system for hospital presenting self-harm and ideation that exists worldwide. However, there are also several limitations of note. As with all observational studies causation cannot be inferred and future studies with designs suited to establish causal inferences are needed. As the study was restricted to ED-presenting self-harm and ideation, results may not be generalisable to individuals in the community who self-harm or have suicidal thoughts. We were limited with the data available and did not have access to child or adult mental health services data which may explain a significant proportion of the likelihood of the outcome. In addition, children’s social care systems and populations vary internationally, and NI has the highest rate of ED-presenting self-harm in the United Kingdom, warranting the replication of these findings in other jurisdictions. The exclusion of individuals that died before the study end date, particularly deaths by suicide, may introduce survival bias and the potential underestimation of self-harm or ideation risk associated with childhood social care contact.

Conclusion

Mental ill-health is a growing public health concern and whilst self-harm and ideation themselves are behaviours that require appropriate support, they are also the largest known predictors of death by suicide. Understanding who is most at risk and who may benefit from targeted interventions is vital to improving mental health outcomes, reducing rates of death by suicide and understanding prevention pathways. Most children in contact with social services do not present to an ED with self-harm or ideation in young adulthood. However, the large and disproportionate burden of self-harm and ideation within this group underscores the need for a policy response and is a prime opportunity for interventions targeted at young adults with a childhood history of contact with social services or with children still in contact with social services or approaching leaving care.

This study highlights two things. The first is the complex background of over 40% of young adults who present to EDs with self-harm or ideation. Understanding the magnitude of childhood adversity amongst this population may help inform health professionals’ and clinicians’ understanding and therapeutic decision-making. The findings warrant consideration during the development or review of clinical guidelines which identify groups and communities that have increased risk of self-harm or ideation and specify models of care to respond to their specific needs following presentation to ED (Health Service Executive Ireland, 2022). Engagement with social services and individuals with lived experience of social care and self-harm or ideation is also recommended as part of this process. The second is the need for multi-agency care. Whilst EDs provide an important setting in which to provide psychosocial assessment and administer brief interventions to individuals who present with self-harm or ideation, early intervention and increased mental health support services for adults that had contact with social services in childhood requires a multi-agency approach with health and social services.

The need to improve young people’s mental health has been a key element of recent independent reviews of children’s social care in England (MacAlister, Reference MacAlister2022), Scotland (Duncan, Reference Duncan2020) and NI (Jones, Reference Jones2023). The NI Review recommended the need for the development of emotional health and well-being services within Social Services separate from clinical Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) (Jones, Reference Jones2023). This study provides evidence to support this recommendation as early intervention may be key to preventing these individuals presenting to EDs with self-harm or ideation in young adulthood. The authors would suggest extending the provision of these services to all levels of contact with social services and not just limit them to children in care as the largest absolute number of young adults presenting to ED with self-harm or ideation come from lower tiers of social services intervention. The Review also recommended the expansion of post-18 years support (Jones, Reference Jones2023). This study illustrates the continued increase in likelihood of self-harm and/or ideation amongst young adults known to social services in childhood, suggesting the need for ongoing support and in particular mental health support after ageing out of the children’s social care system.

Availability of data and materials

Data collected by the Northern Ireland Registry of Self-Harm are confidential and cannot be made available publicly. Access to data is available via the Northern Ireland Trusted Research Environment’s Honest Broker Service for Health and Social Care (HSC) Northern Ireland, once approval from all Health and Social Care Trusts in Northern Ireland has been received. To access data from the Northern Ireland Registry of Self-harm, please contact the Public Health Agency (reception.pha@hscni.net). NHAIS and SOSCARE data are available for research projects in the public interest that relate to Health and Social Care, subject to application and approval by the Honest Broker Service Governance Board (for information contact honestbrokerservice@hscni.net).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Professor Dermot O’Reilly’s significant role in the development of the research programme on children’s social care in Northern Ireland. Dermot sadly died in October 2023. He was a dear friend and Director of the Administrative Data Research Centre Northern Ireland (ADRC NI) since 2014. He will be missed; his work on health and social inequalities will continue in his memory. The authors would like to acknowledge the help provided by the staff of the Honest Broker Service (HBS) within the Business Services Organisation Northern Ireland (BSO). The HBS is funded by the BSO and the Department of Health (DoH). The authors alone are responsible for the interpretation of the data and any views or opinions presented are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the BSO.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Public Health Agency for granting access to data from the Northern Ireland Registry of Self-harm.

The authors would also like to acknowledge Voice of Young People in Care (VOYPIC) and the Data Research Advisory Group for their contribution to the research.

Author contributions

Funding acquisition: AM and DOR. Conceptualisation and data curation: AM. Data validation: SM and AM. Data management and formal analysis: SM. Preparation of manuscript: SM, DOR, ER & AM. Review and editing: SM, DOR, ER & AM. All authors had full access to the data, critically revised the paper for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. SM and AM are guarantors of the work. D O’Reilly, Posthumous Authorship.

Financial support

This work was supported by the UKRI’s Administrative Data Research Centre Northern Ireland (ES/S00744X/1), Medical Research Council Fellowship (MR/P014631/1/) and Health Data Research UK/ DATAMIND (MR/W014386/1). For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical standards

Participant consent was not required as the study used previously held secondary data which is de-identified at the point of access. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) – REF 20/LO/0203.