Introduction

Globally, the proportion of older adults (>60 years) is estimated to almost double between 2015 and 2050, from about 12% to 22% (United Nations, 2015). As the world population ages, it is critical to promote and support healthy ageing processes to improve societal wellbeing and limit its clinical and economic burden (Dietz et al., Reference Dietz, Frey and Kalof1987). The prevalence of late-life depression is 7% among the general older population (Mccall and Kintziger, Reference Mccall and Kintziger2013) and accounts for 5.7% of years lived with disability in those over 60 years old (Killinger, Reference Killinger2012). Depressive symptoms are often overlooked and untreated in older populations, are associated with psychosocial and cognitive decline (Nelson, Reference Nelson2001), and result from a complex interaction between psychological, biological and social factors (Alexopoulos, Reference Alexopoulos2019). One significant determinant that could play a role is transitioning into retirement, whose timing, decision and consequences could be influenced by depressive symptoms, such as loneliness and hopelessness, acting as moderators (Gum et al., Reference Gum, Shiovitz-Ezra and Ayalon2017; Segel-Karpas et al., Reference Segel-Karpas, Ayalon and Lachman2018). Retirement is a major life transition that results in social and psychological transformations (Bosse et al., Reference Bosse, Aldwin, Levenson and Workman-Daniels1991), which pose both threats and opportunities for mental health. On the one hand, as a potentially stressful life event, retirement can have adverse repercussions on individual physical and psychological wellbeing (Portnoi, Reference Portnoi1981). People lose access to social networks, lifestyles and daily routines, as well as potential stimulation, activity and purposes. Conversely, retirement may reduce work-related exposures and improve physical and mental health through complex mechanisms. These could include an increase in social support and in the time available for leisure and healthy activities, and disconnection from work-related stressors (Van Der Heide et al., Reference Van Der Heide, Van Rijn, Robroek, Burdorf and Proper2013; Eibich, Reference Eibich2015). These positive health effects were particularly observed among retirees from strenuous jobs (Belloni et al., Reference Belloni, Meschi and Pasini2016; Blake and Garrouste, Reference Blake and Garrouste2019; Ardito et al., Reference Ardito, Leombruni, Blane and D'errico2020; Carrino et al., Reference Carrino, Glaser and Avendano2020; Fleischmann et al., Reference Fleischmann, Xue and Head2020). Therefore, as we reported in previous research (Vigezzi et al., Reference Vigezzi, Gaetti, Gianfredi, Frascella, Gentile, D'errico, Stuckler, Ricceri, Costa and Odone2021), health behaviours changes (e.g. changes in smoke habit, alcohol consumption, physical activity, time use, social interactions) appeared to be among the most relevant mediators of retirement consequences on olders’ health, affecting life years after the withdrawal from work (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Rice, Wallace, Guralnik and Melzer2007; Vahtera et al., Reference Vahtera, Westerlund, Hall, Sjösten, Kivimäki, Sal, Ferrie, Jokela, Pentti, Singh-Manoux, Goldberg and Zins2009; Celidoni and Rebba, Reference Celidoni and Rebba2017). Nonetheless, current findings are inconclusive. As it has been previously conceptualised (Van Solinge, Reference Van Solinge2007), health consequences of retiring are influenced by the employment history, the job characteristics (Ardito et al., Reference Ardito, Leombruni, Blane and D'errico2020) and the transition to retirement itself, as well as by the availability of socioeconomic resources at the time of retirement and, last but not least, by individuals’ characteristics and appraisal of stress-generating life events (Van Solinge, Reference Van Solinge2007; Augner, Reference Augner2018). As a result of such a complex conceptual model, no conclusive evidence exists on the harm-benefit health balance of retirement. In particular, both older and more recent studies have shown contradictory results on the impact of retirement on mental health outcomes (Bossé et al., Reference Bossé, Aldwin, Levenson and Ekerdt1987; Salokangas and Joukamaa, Reference Salokangas and Joukamaa1991; Gall et al., Reference Gall, Evans and Howard1997; Drentea, Reference Drentea2002; Mein et al., Reference Mein, Martikainen, Hemingway, Stansfeld and Marmot2003; Buxton et al., Reference Buxton, Singleton and Melzer2005; Gill et al., Reference Gill, Butterworth, Rodgers, Anstey, Villamil and Melzer2006; Mojon-Azzi et al., Reference Mojon-Azzi, Sousa-Poza and Widmer2007; Van Solinge, Reference Van Solinge2007; Alavinia and Burdorf, Reference Alavinia and Burdorf2008; Vahtera et al., Reference Vahtera, Westerlund, Hall, Sjösten, Kivimäki, Sal, Ferrie, Jokela, Pentti, Singh-Manoux, Goldberg and Zins2009; Jokela et al., Reference Jokela, Ferrie, Gimeno, Chandola, Shipley, Head, Vahtera, Westerlund, Marmot and Kivimäki2010; Westerlund et al., Reference Westerlund, Vahtera, Ferrie, Singh-Manoux, Pentti, Melchior, Leineweber, Jokela, Siegrist, Goldberg, Zins and Kivimäki2010).

Here we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify the overall association of retirement with depression. As a second aim, we sought to identify potential modifying individual- and contextual-level factors.

Methods

We followed the Prepared Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Liberati et al., Reference Liberati, Altman, Tetzlaff, Mulrow, Gotzsche, Ioannidis, Clarke, Devereaux, Kleijnen and Moher2009; Page et al., Reference Page, Mckenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, Mcdonald, Mcguinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021) and the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000).

Search methods and inclusion criteria

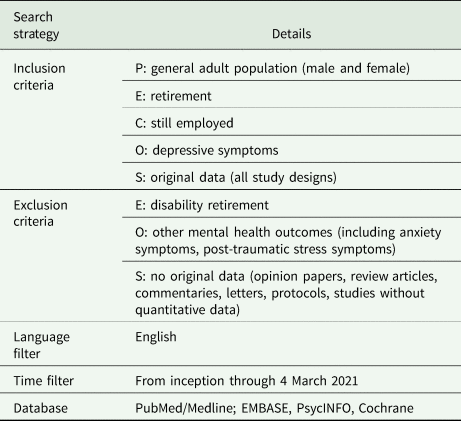

Studies identified searching the electronic databases PubMed/Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library through 4 March 2021 were included. The search strategy was first developed in Medline and then adapted for use in the other databases (online Supplementary Table 1). Briefly, we used a combination of free text and exploded MeSH headings, identifying: (i) the concept of ‘retirement/transition to retirement’ and (ii) ‘depression/depressive symptoms’. Further studies were retrieved from manual reference listing of relevant articles and consultation with experts in the field. Details on inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported in Table 1, according to the Population, Exposure, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design (PECOS) framework (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Brunnhuber, Chalkidou, Chalmers, Clarke, Fenton, Forbes, Glanville, Hicks, Moody, Twaddle, Timimi and Young2006; Higgins and Green, Reference Higgins and Green2013). Our inclusion criteria were limited to those studies: reporting original data from quantitative analysis, providing effect sizes (ESs) of the association between retirement (exposure of interest) and depression (outcome of interest); natural experiments (Stuckler, Reference Stuckler2017; Ronchetti et al., Reference Ronchetti, Toffolutti, Mckee and Stuckler2020), observational studies with prospective, retrospective and cross-sectional designs; and written in English. An extensive definition of retirement and retirement status was used: depending on study design, both retired status and transition to retirement were included as exposure of interest; we considered all retirement types, apart from retirement only for disability, which was excluded. Depression-related outcomes of interest included: depressive symptoms, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), or International Classification of Diseases scale (ICD)-based diagnosis as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. We excluded opinion papers (i.e. editorials, narrative reviews, commentaries and letters to the Editor) not providing original data. Systematic reviews were also excluded but screened to retrieve relevant original studies. The review's protocol was drafted and approved by authors before conduction (not archived on public databases).

Table 1. A priori defined inclusion and exclusion criteria according to the Population (P), Exposure (E), Comparison (C), Outcomes (O) and Study design (S) (PECOS) framework

Study selection, data extraction and quality appraisal

Identified studies were independently reviewed for eligibility by two authors (V.G. and G.P.V.) in a two-step process; a first screening was performed based on title and abstract. Then, full texts were retrieved for a second screening. At both stages, disagreements among reviewers were resolved by consensus and by consulting a third senior author (A.O.) when disagreement persisted. Data were independently extracted by two authors (V.G. and G.P.V.), supervised by a third author (A.O.), using an ad-hoc developed data extraction spreadsheet. The data extraction spreadsheet was piloted on ten randomly selected papers and modified accordingly. Data extraction included: full reference details, country of study conduction, study design, study setting, study population details, sample size, exposure details, outcomes of interest, including validated assessment tools for depression, and quantitative results, including ESs and corresponding confidence intervals (CIs). Corresponding authors were contacted by e-mail in case of incomplete data. Quality appraisal of included studies was carried out applying the 14-item scoring system developed by Shim et al. for population-based studies on retirement as a risk factor (Shim et al., Reference Shim, Gimeno, Pruitt, Mcleod, Foster and BC2013). As determined by consensus following the review methodology literature, we consider of high quality the studies with at least ⩾75% of the highest score.

Data pooling and meta-analysis

We performed descriptive analysis to report and pool the characteristics of included studies using ranges and average values. With regard to the pre-specified outcomes of interest, we would expect variability between studies, e.g. by study design and population. We, therefore, applied random-effects meta-analyses to acquire estimates of the association between retiring and risk of depression/depressive symptoms, rather than to assume a single true value in a fixed-effects approach (Higgins and Green, Reference Higgins and Green2013). Moreover, a random effect model is highly recommended when high heterogeneity is expected or detected. Pooled ESs were calculated as odd ratios (ORs) (Ter Hoeve et al., Reference Ter Hoeve, Ekblom, Galanti, Forsell and Nooijen2020). When the included studies reported ESs as regression beta coefficients with corresponding standard errors (s.e.s), we mathematically converted them into ORs with corresponding CIs (Bland and Altman, Reference Bland and Altman2000; Hailpern and Visintainer, Reference Hailpern and Visintainer2003). We also included studies that reported ESs as χ 2 or ρ correlation coefficients with corresponding total sample sizes or as mean differences with sample sizes and corresponding correlations. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic (see online Supplementary Table 3 for details) and visual inspection of funnel plots. We performed sensitivity analyses progressively limiting meta-analysis to: (i) high-quality studies; (ii) high-quality studies using validated scales to diagnose depression; (iii) high-quality longitudinal studies using validated scales to diagnose depression. Moreover, we conducted a subgroup meta-analysis by gender strata and study design.

We assessed publication bias with funnel plot visual inspection (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher, Oxman, Savovic, Schulz, Weeks and Sterne2011) and the Begg and Mazumdar (Reference Begg and Mazumdar1994) and Egger et al. (Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder1997) tests. A ‘trim and fill’ method was used if publication bias was detected (Duval and Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000; Gianfredi et al., Reference Gianfredi, Nucci, Fatigoni, Salvatori, Villarini and Moretti2020) to estimate potential missing studies which contribute to the funnel plot's asymmetry (Sutton et al., Reference Sutton, Duval, Tweedie, Abrams and Jones2000). This method assumes that the most extreme ES studies have not been reported, biasing the overall ES estimates (Shi and Lin, Reference Shi and Lin2019). Meta-analyses were conducted using ProMeta3® (Internovi, Milan, Italy) software.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

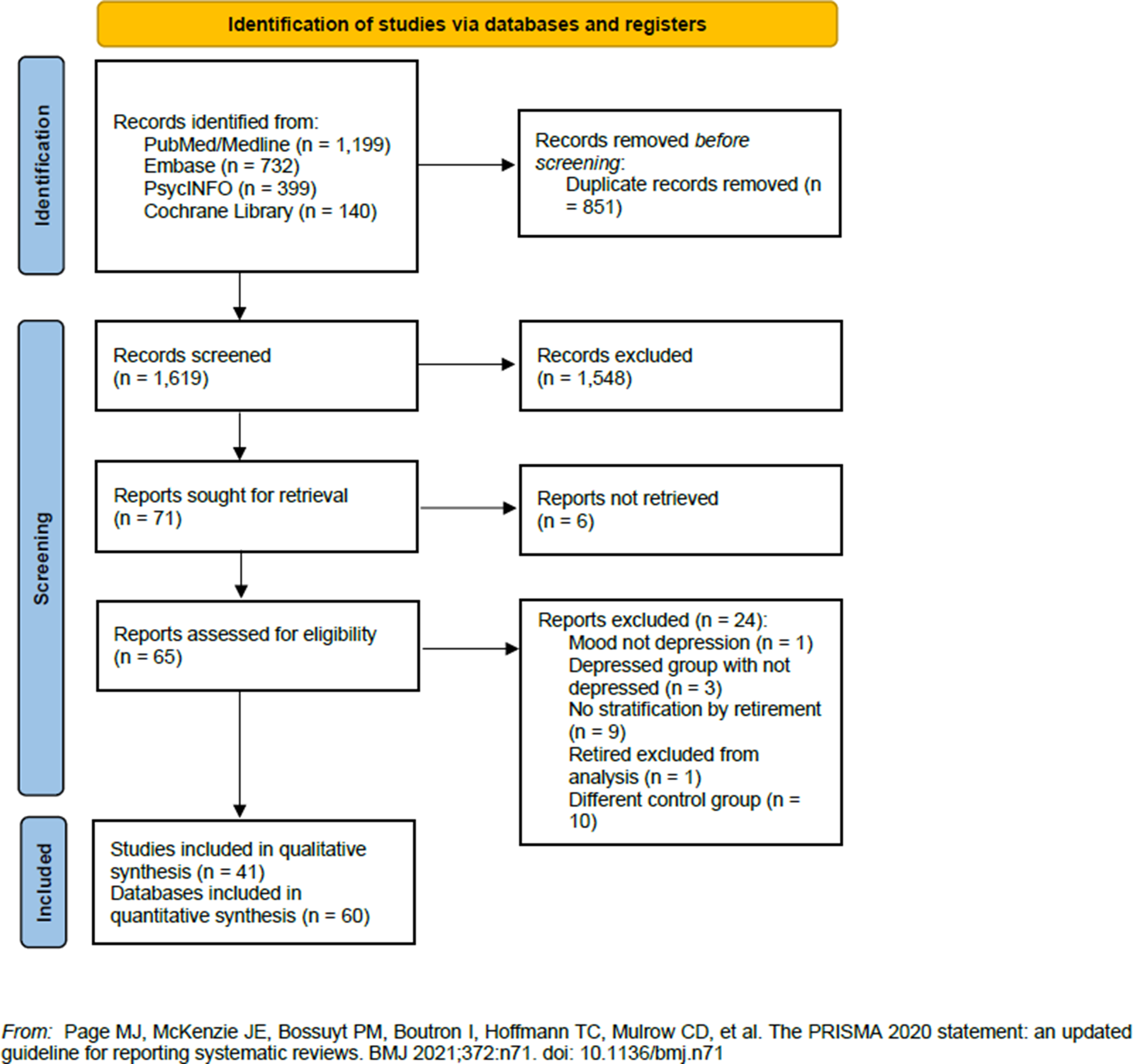

We identified 2470 studies by searching the selected databases and listing references of relevant articles. After removing duplicates, 1619 records were retrieved. Papers were screened and selected, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (1548 records were excluded after first screening; six reports were not retrieved in full text; 24 were excluded with reasons), resulting in 41 papers meeting our inclusion criteria (Farakhan et al., Reference Farakhan, Lubin and O'connor1984; Borson et al., Reference Borson, Barnes, Kukull, Okimoto, Veith, Inui, Carter and Raskind1986; Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, House and Morgan1991; Pahkala et al., Reference Pahkala, Kivela and Laippala1992; Midanik et al., Reference Midanik, Soghikian, Ransom and Tekawa1995; Reitzes et al., Reference Reitzes, Mutran and Fernandez1996; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Mutran, Reitzes and Sudha1998; Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002; Buxton et al., Reference Buxton, Singleton and Melzer2005; Tuohy et al., Reference Tuohy, Knussen and Wrennall2005; Butterworth et al., Reference Butterworth, Gill, Rodgers, Anstey, Villamil and Melzer2006; Mojon-Azzi et al., Reference Mojon-Azzi, Sousa-Poza and Widmer2007; Alavinia and Burdorf, Reference Alavinia and Burdorf2008; Schwingel et al., Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009; Coursolle et al., Reference Coursolle, Sweeney, Raymo and Ho2010; Behncke, Reference Behncke2012; Calvo et al., Reference Calvo, Sarkisian and Tamborini2013; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Stewart and Dewey2013; Gayman et al., Reference Gayman, Pai, Kail and Taylor2013; Leinonen et al., Reference Leinonen, Lahelma and Martikainen2013; Airagnes et al., Reference Airagnes, Lemogne, Consoli, Schuster, Zins and Limosin2015, Reference Airagnes, Lemogne, Hoertel, Goldberg, Limosin and Zins2016; Bretanha et al., Reference Bretanha, Facchini, Nunes, Munhoz, Tomasi and Thume2015; Olesen et al., Reference Olesen, Rod, Madsen, Bonde and Rugulies2015; Belloni et al., Reference Belloni, Meschi and Pasini2016; Calvó-Perxas et al., Reference Calvó-Perxas, Vilalta-Franch, Turro-Garriga, Lopez-Pousa and Garre-Olmo2016; Mosca and Barrett, Reference Mosca and Barrett2016; Park and Kang, Reference Park and Kang2016; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Mor Barak and Gallo2016; Heller-Sahlgren, Reference Heller-Sahlgren2017; Shiba et al., Reference Shiba, Kondo, Kondo and Kawachi2017; Arias-De La Torre et al., Reference Arias-De La Torre, Vilagut, Martin, Molina and Alonso2018; Augner, Reference Augner2018; Fernández-Niño et al., Reference Fernández-Niño, Bonilla-Tinoco, Manrique-Espinoza, Romero-Martinez and Sosa-Ortiz2018; Sheppard and Wallace, Reference Sheppard and Wallace2018; Van Den Bogaard and Henkens, Reference Van Den Bogaard and Henkens2018; Anxo et al., Reference Anxo, Ericson and Miao2019; Kolodziej and García-Gómez, Reference Kolodziej and García-Gómez2019; Noh et al., Reference Noh, Kwon, Lee, Oh and Kim2019; Matta et al., Reference Matta, Carette, Zins, Goldberg, Lemogne and Czernichow2020; Han, Reference Han2021). Characteristics of included studies are reported in Table 2. Studies were published between 1984 and 2021, with almost one third (n = 12, 29.3%) published in the last 5 years. The majority of the studies (n = 21, 51.2%) were conducted in Europe (United Kingdom, n = 3; France, n = 3; Finland, n = 2; Sweden, n = 1; Spain, n = 1; Switzerland, n = 1; Denmark, n = 1; Ireland, n = 1; Scotland, n = 1; multi-centric European studies, n = 5) and in the USA (n = 13, 31.7%). Four studies were conducted in Asia, one in Brazil, one in Australia; four were multi-centre studies conducted at the global and European level.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the studies selection process.

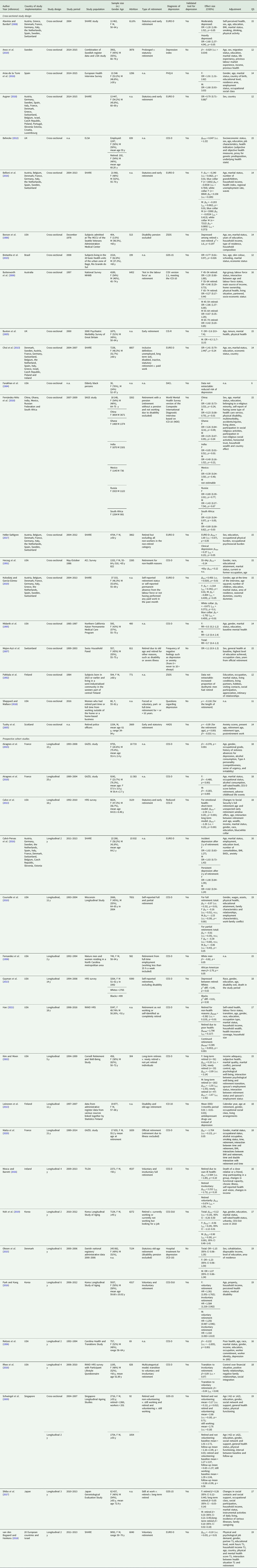

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics of the included studies stratified by study design and listed in alphabetical order and by study design

ρ, Pearson correlation; ACL, Americans' Changing Lives; ATET, Average Treatment Effect on the Treated; BALD, Basic Activities of Daily Living; BMI, Body Mass Index; BDI, Beck Depression Inventor; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CIS-R, Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised; CCRC, Continuing Care Retirement Community; CI, Confidence Interval; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview version 2.1; DACL, Depression Adjective Check List; DDD, Defined Daily Dose; ELSA, English Longitudinal Study of Ageing; EURO-D, Euro Depression-scale; F, Female; FE, Fixed Effects; FEIV, Fixed Effects Instrumental Variables; GAZEL, Gaz et Electricité; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HR, hazard ratio; HRS, Health and Retirement Study; ICD, International Classification of Diseases scale; IV, Instrumental Variables; LISA, Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies; M, Male; MCCU, Medical Comprehensive Care Unit; MHWB, National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being; n.a., not available; n.s., not significant; OLS, Ordinary Least Squares; OR, Odd Ratio; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; QS, Quality Score; RR, relative risk; SAGE, Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health; s.e., Standard Error; SHARE, Survey on Health and Ageing in Europe; TILDA, The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; y, years; ZSDS, Zung Self-rating Depression Scale.

a Odds ratios and corresponding confidence intervals were calculated as the reverse odds ratios for the association between depression and employment compared to retired people.

Nineteen (46.3%) studies were longitudinal studies; their follow-up time ranged from 2 to 25 years, with most of them (n = 12, 60.0%) having less than 10 years of follow-up. Most of the longitudinal analyses were derived from the Survey on Health and Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE, n = 8), followed by the Health and Retirement Study (HRS, n = 4) and the Gaz et Electricité cohort study (GAZEL, n = 3). Twenty-one studies (51.2%) had a cross-sectional study design, while only one study reported both cross-sectional and longitudinal data (Schwingel et al., Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009). Overall, sample sizes of included studies ranged from 30 (Farakhan et al., Reference Farakhan, Lubin and O'connor1984) to 245 082 subjects (Olesen et al., Reference Olesen, Rod, Madsen, Bonde and Rugulies2015) (mean: 14 423 subjects, median: 4189 subjects); longitudinal studies sample sizes ranged between 458 and 245 082 subjects (mean: 21 884 subjects, median: 7134 subjects). The majority of included study populations’ age ranged between 45 and 80 years (n = 38, 92.7%). One study included only males (Tuohy et al., Reference Tuohy, Knussen and Wrennall2005) and one only females (Sheppard and Wallace, Reference Sheppard and Wallace2018). Details on study populations are reported in Table 2, which also reports information on the type of retirement, available for 76% of studies, and outcomes assessment.

More than ninety per cent of included studies used validated tools to diagnose depression-related outcomes, including the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) in 17 studies (41.5%), the Euro Depression-scale (EURO-D) in eight studies (19.5%), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in three studies (7.1%) and the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale (ZSDS) in two studies (4.9%). The International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) was used to identify depression-related conditions in three studies (7.1%). The Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), the Depression Adjective Check List (DACL) and the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R) were used in only one study each (Table 2). Three studies (7.1%) used non validated tools to identify depression-related outcomes (Mojon-Azzi et al., Reference Mojon-Azzi, Sousa-Poza and Widmer2007; Sheppard and Wallace, Reference Sheppard and Wallace2018; Anxo et al., Reference Anxo, Ericson and Miao2019). Included studies’ quality score (QS) is also reported in Table 2. The mean QS was 15.5/20. The lowest QS was 6 (Farakhan et al., Reference Farakhan, Lubin and O'connor1984), whereas the highest was 19 (Schwingel et al., Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009; Olesen et al., Reference Olesen, Rod, Madsen, Bonde and Rugulies2015; Park and Kang, Reference Park and Kang2016; Van Den Bogaard and Henkens, Reference Van Den Bogaard and Henkens2018). Question 7 [Is retirement a main effect, co-variable, confounder, or interaction in the study?] (n = 15) and Question 13 [Was the loss to follow-up appropriately addressed and/or adequately described in the study?] (n = 11) reported the lowest scores (for details on quality appraisal, see online Supplementary Table 2).

Retirement and depression: qualitative reporting

Overall, more than one third (n = 15, 36.6%) of included studies reported a statistically significant negative association between retirement and depression (i.e. retirement decreased the risk of depression) (Farakhan et al., Reference Farakhan, Lubin and O'connor1984; Tuohy et al., Reference Tuohy, Knussen and Wrennall2005; Butterworth et al., Reference Butterworth, Gill, Rodgers, Anstey, Villamil and Melzer2006; Schwingel et al., Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009; Coursolle et al., Reference Coursolle, Sweeney, Raymo and Ho2010; Calvo et al., Reference Calvo, Sarkisian and Tamborini2013; Airagnes et al., Reference Airagnes, Lemogne, Consoli, Schuster, Zins and Limosin2015, Reference Airagnes, Lemogne, Hoertel, Goldberg, Limosin and Zins2016; Bretanha et al., Reference Bretanha, Facchini, Nunes, Munhoz, Tomasi and Thume2015; Belloni et al., Reference Belloni, Meschi and Pasini2016; Augner, Reference Augner2018; Van Den Bogaard and Henkens, Reference Van Den Bogaard and Henkens2018; Kolodziej and García-Gómez, Reference Kolodziej and García-Gómez2019; Matta et al., Reference Matta, Carette, Zins, Goldberg, Lemogne and Czernichow2020; Han, Reference Han2021), 14.6% (n = 6) reported a positive association (Pahkala et al., Reference Pahkala, Kivela and Laippala1992; Alavinia and Burdorf, Reference Alavinia and Burdorf2008; Park and Kang, Reference Park and Kang2016; Heller-Sahlgren, Reference Heller-Sahlgren2017; Shiba et al., Reference Shiba, Kondo, Kondo and Kawachi2017; Arias-De La Torre et al., Reference Arias-De La Torre, Vilagut, Martin, Molina and Alonso2018), while 48.8% (n = 20 studies) did not report statistically significant associations between retirement and depression (Borson et al., Reference Borson, Barnes, Kukull, Okimoto, Veith, Inui, Carter and Raskind1986; Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, House and Morgan1991; Midanik et al., Reference Midanik, Soghikian, Ransom and Tekawa1995; Reitzes et al., Reference Reitzes, Mutran and Fernandez1996; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Mutran, Reitzes and Sudha1998; Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002; Buxton et al., Reference Buxton, Singleton and Melzer2005; Mojon-Azzi et al., Reference Mojon-Azzi, Sousa-Poza and Widmer2007; Behncke, Reference Behncke2012; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Stewart and Dewey2013; Gayman et al., Reference Gayman, Pai, Kail and Taylor2013; Leinonen et al., Reference Leinonen, Lahelma and Martikainen2013; Olesen et al., Reference Olesen, Rod, Madsen, Bonde and Rugulies2015; Calvó-Perxas et al., Reference Calvó-Perxas, Vilalta-Franch, Turro-Garriga, Lopez-Pousa and Garre-Olmo2016; Mosca and Barrett, Reference Mosca and Barrett2016; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Mor Barak and Gallo2016; Fernández-Niño et al., Reference Fernández-Niño, Bonilla-Tinoco, Manrique-Espinoza, Romero-Martinez and Sosa-Ortiz2018; Sheppard and Wallace, Reference Sheppard and Wallace2018; Anxo et al., Reference Anxo, Ericson and Miao2019; Noh et al., Reference Noh, Kwon, Lee, Oh and Kim2019). The reported ESs included: β coefficients (β) (n = 19), ORs (n = 11), χ 2 (n = 3), relative risks (RRs) (n = 1), hazard ratios (HRs) (n = 1) and mean differences (n = 2). Almost all included studies reported adjusted effect estimates (i.e. accounting for age, gender, education, health and marital status; details on multivariate models’ adjustments are reported in Table 2). Two studies reported separate data based on the severity of depression (Alavinia and Burdorf, Reference Alavinia and Burdorf2008; Heller-Sahlgren, Reference Heller-Sahlgren2017); two studies reported separate data for short-term (incident) and long-term (persistent) depression (Calvo et al., Reference Calvo, Sarkisian and Tamborini2013; Calvó-Perxas et al., Reference Calvó-Perxas, Vilalta-Franch, Turro-Garriga, Lopez-Pousa and Garre-Olmo2016); two studies reported separate data by age group (Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, House and Morgan1991; Butterworth et al., Reference Butterworth, Gill, Rodgers, Anstey, Villamil and Melzer2006). Some studies differentiated the analysis by type of retirement, distinguishing between full and partial retirement (Coursolle et al., Reference Coursolle, Sweeney, Raymo and Ho2010), retirement for health and non-health reasons (Han, Reference Han2021), long-term and new retirement (Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002; Shiba et al., Reference Shiba, Kondo, Kondo and Kawachi2017), voluntary and involuntary retirement (Mosca and Barrett, Reference Mosca and Barrett2016; Park and Kang, Reference Park and Kang2016; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Mor Barak and Gallo2016), or considered retirement jointly with volunteering (Schwingel et al., Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009). One study reported separate data for cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis (Schwingel et al., Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009), as reported above.

Fourteen studies reported separate data for men and women (Midanik et al., Reference Midanik, Soghikian, Ransom and Tekawa1995; Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002; Buxton et al., Reference Buxton, Singleton and Melzer2005; Butterworth et al., Reference Butterworth, Gill, Rodgers, Anstey, Villamil and Melzer2006; Coursolle et al., Reference Coursolle, Sweeney, Raymo and Ho2010; Olesen et al., Reference Olesen, Rod, Madsen, Bonde and Rugulies2015; Airagnes et al., Reference Airagnes, Lemogne, Hoertel, Goldberg, Limosin and Zins2016; Belloni et al., Reference Belloni, Meschi and Pasini2016; Calvó-Perxas et al., Reference Calvó-Perxas, Vilalta-Franch, Turro-Garriga, Lopez-Pousa and Garre-Olmo2016; Park and Kang, Reference Park and Kang2016; Shiba et al., Reference Shiba, Kondo, Kondo and Kawachi2017; Arias-De La Torre et al., Reference Arias-De La Torre, Vilagut, Martin, Molina and Alonso2018; Fernández-Niño et al., Reference Fernández-Niño, Bonilla-Tinoco, Manrique-Espinoza, Romero-Martinez and Sosa-Ortiz2018; Kolodziej and García-Gómez, Reference Kolodziej and García-Gómez2019); two studies reported separate data based on ethnicity (Gayman et al., Reference Gayman, Pai, Kail and Taylor2013; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Mutran, Reitzes and Sudha1998); one study reported independent results based on the country (Fernández-Niño et al., Reference Fernández-Niño, Bonilla-Tinoco, Manrique-Espinoza, Romero-Martinez and Sosa-Ortiz2018), so they were considered separately. Among included studies, data from two studies were not extractable (Farakhan et al., Reference Farakhan, Lubin and O'connor1984; Pahkala et al., Reference Pahkala, Kivela and Laippala1992). Three studies did not report ESs and CIs (Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, House and Morgan1991; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Mutran, Reitzes and Sudha1998) or outcomes comparable to other works (Leinonen et al., Reference Leinonen, Lahelma and Martikainen2013) and were not included in the quantitative analysis.

Retirement and depression: quantitative reporting and meta-analysis

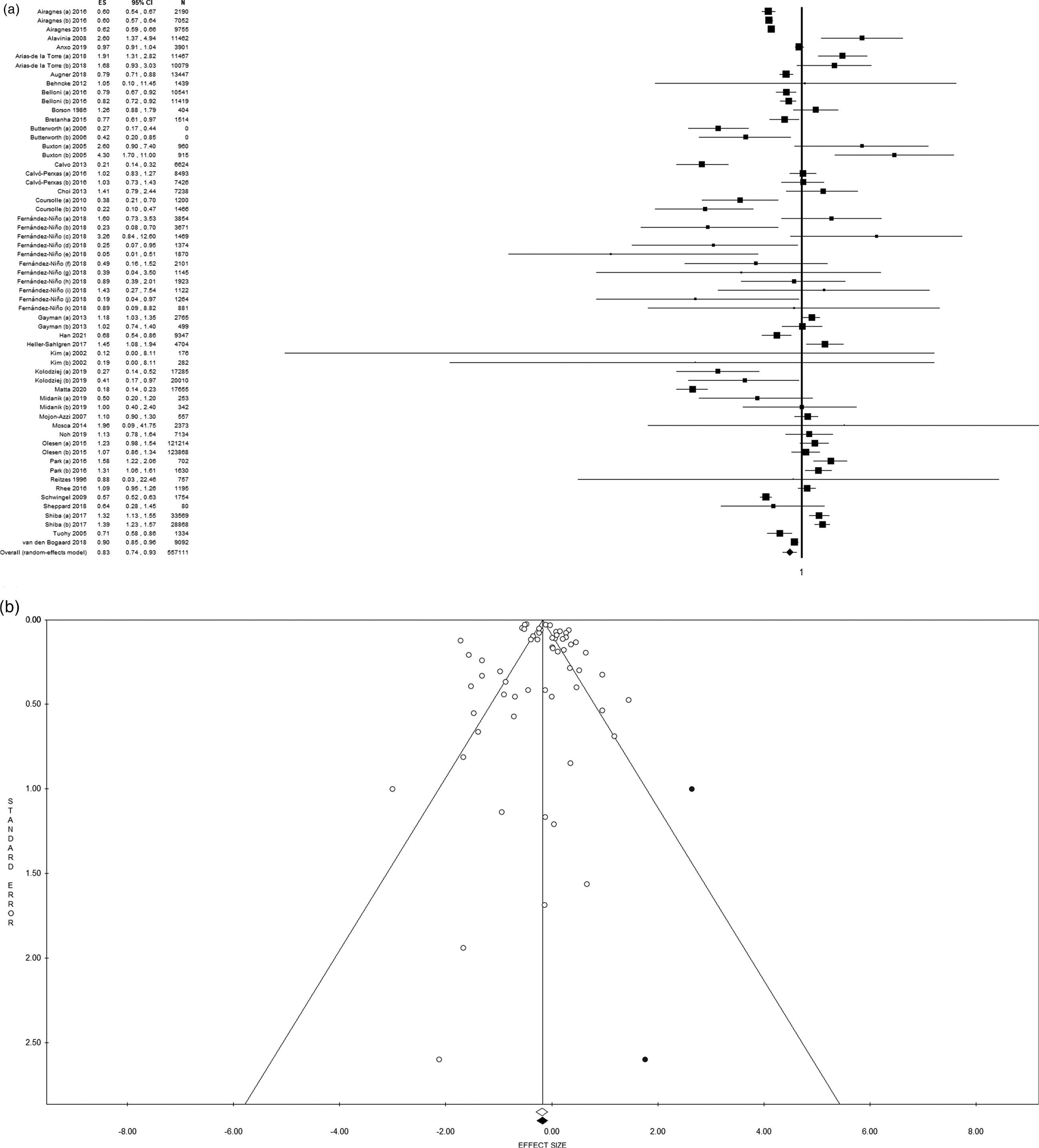

Quantitative pooling of effect estimates was conducted on a total of 557 111 subjects from 60 different databases. Overall, the pooled ES for the risk of depression when retired is 0.83 (95% CI = 0.74–0.93, p-value = 0.001, Fig. 2a), with high statistical heterogeneity (χ 2 = 895.19, df = 59, I 2 = 93.41, p-value < 0.001). The funnel plot resulted slightly asymmetrical at visual inspection, showing a low potential for publication bias, not confirmed by Egger's linear regression test (Intercept 0.53, t = 0.78, p-value = 0.439). Moreover, the ES change after the trim and fill method was minor [0.84 (95% CI = 0.75–0.94)], and two studies were trimmed in the lower right quarter of the funnel plot (Fig. 2b), suggesting few studies of poor quality could be missing.

Fig. 2. (a) Forest plot and (b) funnel plot (after trim and fill method) of the meta-analysis assessing the association between retirement and depression. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

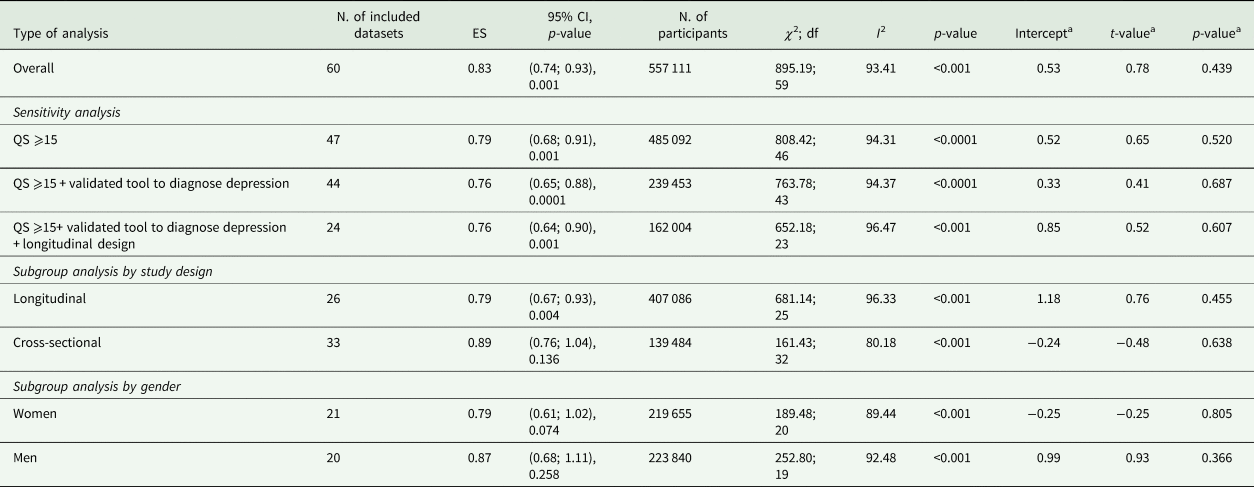

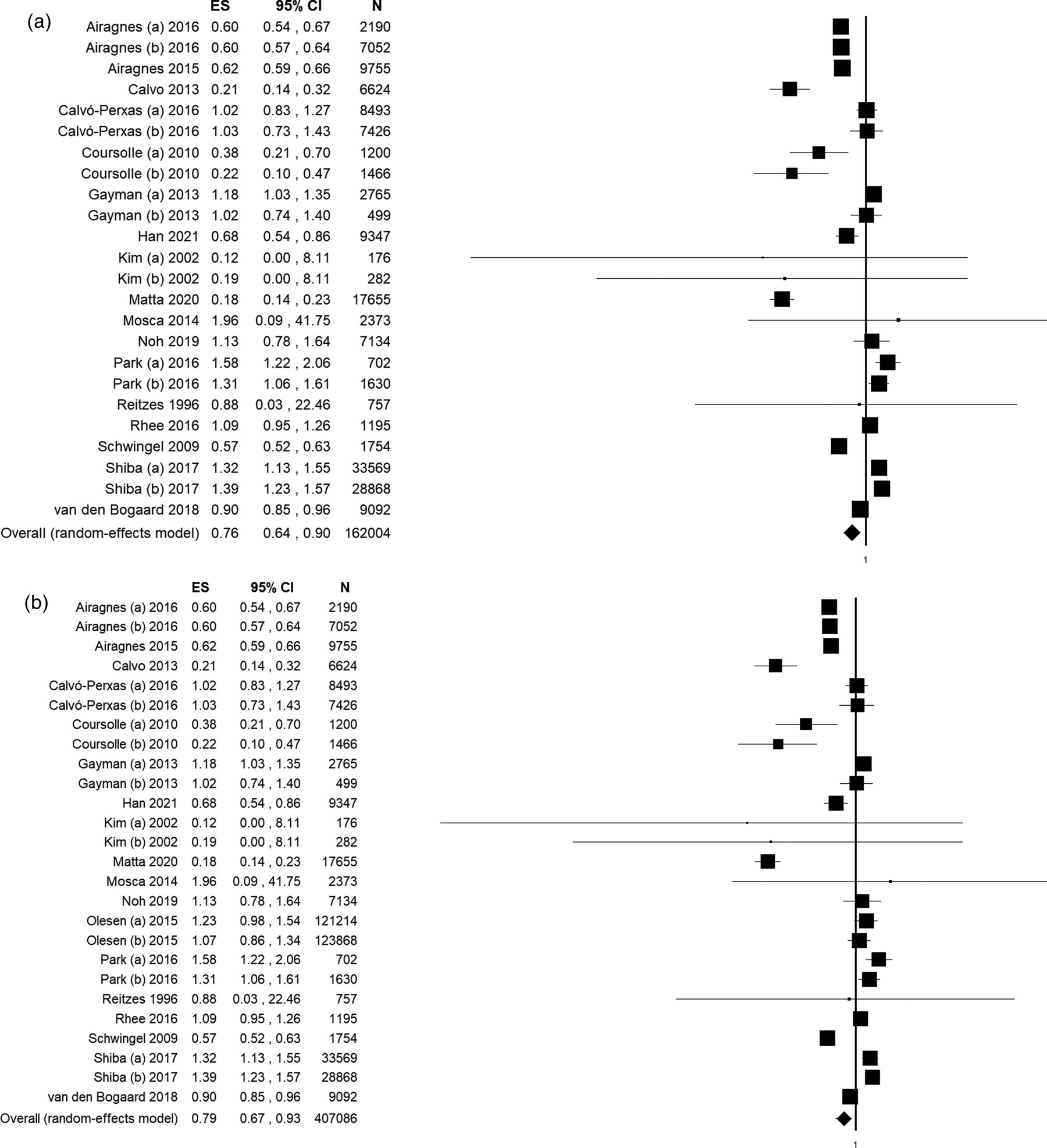

Results of the sensitivity and subgroup analyses are summarised in Table 3. We performed a sensitivity analysis, progressively increasing the quality of included studies in order to test our overall results’ consistency. First, we limited the analysis to studies of the highest quality (QS equal or higher than 15): 47 datasets and 485 092 subjects were included in the meta-analysis, reporting a consistent statistically significant association between retirement and decreased risk of depression (ES = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.68–0.91, p-value = 0.001, online Supplementary Fig. 1a). Then, we limited the analysis to studies with high QS and using validated assessment tools to diagnose depression. In this analysis, 44 datasets were included, for a total of 239 453 subjects, strengthening the significant association between retirement and decreased risk of depression (ES = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.65–0.88, p-value < 0.001, online Supplementary Fig. 1b). Finally, only studies (i) with a QS equal or higher than 15, (ii) using validated assessment tools to diagnose depression and (iii) with a longitudinal study design were included. We report a statistically significant association between retirement and depression (ES = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.64–0.90, p-value = 0.001, Fig. 3a) based on 24 datasets and 162 004 subjects. High statistical heterogeneity and slight visual asymmetry of the funnel plot were observed at each step of the analysis (Table 3), with the exception of the last one restricted to longitudinal studies of the highest quality, when estimated ES did not change with the trim and fill method.

Table 3. Results of overall, sensitivity and subgroup analyses

df, degree of freedom; ES, Effect Size; N., number; QS, quality score

a Egger's linear regression test.

Fig. 3. Forest plot of subgroups meta-analysis assessing the association between retirement and depression limited to: (a) studies with a quality score (QS) equal or higher than 15, using validated diagnostic tools and with a longitudinal study design; (b) longitudinal studies. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

These results appeared to be dragged by longitudinal studies as, when considering data from longitudinal studies only (26 datasets, 407 086 subjects), a statistically significant association between retirement and depression was equally found (ES = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.67–0.93, p-value = 0.004), with high statistical heterogeneity (χ 2 = 681.14, df = 25, I 2 = 96.33, p-value < 0.001), but no publication bias, as confirmed by funnel visual inspection and Egger's test (Intercept 1.18, t = 0.76, p-value = 0.455, Table 3, Fig. 3b). On the contrary, no statistically significant association resulted when quantitative pooling was limited to cross-sectional studies (33 datasets, 139 484 subjects) (Table 3, online Supplementary Fig. 2a). In this case, publication bias was suggested by funnel plot visual inspection.

Gender-strata meta-analyses are reported in online Supplementary Fig. 2b and 2c. When only considering women, the analysis included 21 datasets and a total of 219 655 subjects, reporting no statistically significant association between retirement and depression (pooled ES = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.61–1.02, p-value = 0.074) and high heterogeneity (Table 3). About men, the analysis included 20 datasets, for a total of 223 840 participants, reporting a pooled ES of 0.87 (95% CI = 0.68–1.11, p-value = 0.258) and high heterogeneity between studies (Table 3). In both cases, evidence of publication bias was suggested by funnel plot.

Discussion

Pooled data from 41 original studies and more than half a million subjects suggested that retirement or transition to retirement reduce by nearly 20% the risk of depression or depressive symptoms; such estimates remain consistent when limiting the analysis to longitudinal and high-quality studies.

Before interpreting our findings further, we must account for the considerable heterogeneity among the included studies, which might limit the generalisability of pooled effect estimates. To overcome this and test the results level of strength, we first applied a random-effect model. Secondly, we conducted sensitivity and stratified meta-analyses by study design and QS. The reasons behind the high level of heterogeneity among the included studies are to be explored in light of, on one side, the wide variety of studies’ designs, settings and populations, definitions and methodological quality and, on the other side, of the complex, multi-determinant and multi-mediator relationship between the process of retirement and mental health and wellbeing (Pesaran et al., Reference Pesaran, Shin and Smith1999; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, Reference Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal2008; Behncke, Reference Behncke2012; Oksanen and Virtanen, Reference Oksanen and Virtanen2012; Insler, Reference Insler2014; Eibich, Reference Eibich2015). We could not retrieve further evidence on the reasons: even excluding one dataset at a time in the meta-analysis to identify potential outliers, heterogeneity persisted (online Supplementary Table 3). However, sensitivity analyses confirmed the results’ consistency.

Despite half of the retrieved studies being cross-sectional, which did not allow us to explore causality, they accounted for less than one-third of included subjects. Another limitation to consider is that duration of retirement was not reported in most studies, so we could not differentiate among the potential risk of depression for short- or long-term exposure to retirement. A subgroup analysis considering the work before retiring was not possible since only two included studies stratified results for this variable (Belloni et al., Reference Belloni, Meschi and Pasini2016; Kolodziej and García-Gómez, Reference Kolodziej and García-Gómez2019). Lastly, even if most of the analysed data came from administrative databases or surveys designed for other purposes, some studies had small sample sizes with poor precision in effect estimates.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis pooling all original studies investigating the association of retirement with prevalent and incident depression. We used a comprehensive range of databases and search terms to maximise the number of studies retrieved and minimise the chance of publication bias. Besides, further studies were retrieved from the reference listing of relevant articles. Such a comprehensive and rigorous summary of the available evidence offers several meaningful insights, valuable to plan, implement and evaluate public health and preventive strategies, public policies, as well as future avenues of research.

Despite the well-known assumption that considers retirement as a potentially stressful life event (Kremer, Reference Kremer1985; Ekerdt, Reference Ekerdt1987; Salokangas and Joukamaa, Reference Salokangas and Joukamaa1991), one of our review's critical findings is that retiring does not necessarily harm an individual's mental health but possibly decrease the risk of depression, as a balance of contextual and individual-level variables impact on such association. In conceptual frameworks proposed in the ageing research literature (Van Solinge, Reference Van Solinge2007), these variables were categorised into: (i) characteristics of the retirement transition, (ii) characteristics of the job, (iii) access to resources, (iv) individual appraisal and (v) gender.

Characteristics of the transition refer to the type and conditions of retirement, which were available in 76% of included studies. For instance, we report different impacts on depression between voluntary and involuntary retirement, with the more considerable impact of the latter (Mosca and Barrett, Reference Mosca and Barrett2016), suggesting elements of desirability and degree of control might play a role in the association (Van Solinge, Reference Van Solinge2007).

There is extensive literature on how employment characteristics influence health after retirement (Hernberg, Reference Hernberg2001; Robroek et al., Reference Robroek, Schuring, Croezen, Stattin and Burdorf2013; De Wind et al., Reference De Wind, Geuskens, Ybema, Blatter, Burdorf, Bongers and Van Der Beek2014, Reference De Wind, Geuskens, Ybema, Bongers and Van Der Beek2015; Soh et al., Reference Soh, Zarola, Palaiou and Furnham2016; Ardito et al., Reference Ardito, Leombruni, Blane and D'errico2020). As emerges from original data, among job characteristics, employment history, time pressure, workload and physical demand may impact the risk of mental health disorders’ onset after retirement (Thoits, Reference Thoits1983; Shultz et al., Reference Shultz, Morton and Weckerle1998).

With reference to resources, access to social and financial resources around retirement might compensate and mitigate the impact of lifestyle changes and the psychological consequences of retiring. We reviewed data where the risk of depression at retirement is differentially distributed by household socioeconomic status (Arias-De La Torre et al., Reference Arias-De La Torre, Vilagut, Martin, Molina and Alonso2018), marital and family relations (Park and Kang, Reference Park and Kang2016), social engagement (Sabbath et al., Reference Sabbath, Lubben, Goldberg, Zins and Berkman2015; Shiba et al., Reference Shiba, Kondo, Kondo and Kawachi2017): as the studies suggest, reliable financial resources, social networks and marriage can mitigate negative health repercussions of retirement (Deeg and Bath, Reference Deeg and Bath2003).

Concerning individual appraisal, personality characteristics influence the meaning assigned to retirement and the ability to cope with this change. Negative expectations and fears about retirement are more likely related to adverse repercussions on individuals’ wellbeing (Barnes-Farrell, Reference Barnes-Farrell2003). Moreover, having confidence in coping with changes determines fewer difficulties in adjusting to retirement (Van Solinge and Henkens, Reference Van Solinge and Henkens2005).

Regarding gender, differences in primary role between women and men, at home and work, respectively, could explain differences in adapting to the event and in health outcomes by gender (Moen, Reference Moen1996), but need to be further explored.

Overall and sensitivity analyses results are consistent with other reviews on the topic. Van Der Heide et al. (Reference Van Der Heide, Van Rijn, Robroek, Burdorf and Proper2013) focused on mental health and antidepressant use in longitudinal studies. They registered an improvement in mental health shortly after retirement, possibly linked to work pressure reduction, even if with gender differences. Schaap et al. (Reference Schaap, De Wind, Coenen, Proper and Boot2018) analysed the health effects of an exit from work across different socioeconomic groups. They found out that, despite significant heterogeneity, withdrawal from work had more positive effects among employees with a higher socioeconomic status than with a lower position. On the contrary, a systematic review was previously conducted on the effects of working or volunteering beyond statutory retirement ages on mental health by Maimaris et al. (Reference Maimaris, Hogan and Lock2010); they suggested that, through the mechanism of maintaining a productive societal role with a continued income and social support, working beyond retirement age might be beneficial for mental health. Nevertheless, the benefits were not universal, but they varied greatly by lifestyles, self-esteem and socioeconomic status.

Implications for public health policies and practice

Regarding public health and preventive strategies, we demonstrated that, besides other factors influencing the risk of late-life depression, transition to retirement, as a life event that almost the entire population experience at some point (Clark and Oswald, Reference Clark and Oswald1994), has an independent effect in itself. The transition is differentially distributed by contextual and individual-level characteristics and, as such, could be identified as a target point for mental health prevention, including both primary and secondary interventions. We claim that primary prevention interventions, aimed at promoting healthy lifestyles and supporting social roles, could be effectively directed towards subjects who do not benefit from retirement flexibility and its protective effect on short- and long-term risk of late-life depression (Smit et al., Reference Smit, Ederveen, Cuijpers, Deeg and Beekman2006; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Van Sluijs and Ogilvie2012; Lindwall et al., Reference Lindwall, Berg, Bjälkebring, Buratti, Hansson, Hassing, Henning, Kivi, König, Thorvaldsson and Johansson2017). As life-course transitions tend to bring along lifestyle changes, synchronising them with public health interventions might be a successful approach (Ben-Shlomo and Kuh, Reference Ben-Shlomo and Kuh2002; Werkman et al., Reference Werkman, Hulshof, Stafleu, Kremers, Kok, Schouten and Schuit2010; Heaven et al., Reference Heaven, Brown, White, Errington, Mathers and Moffatt2013, Reference Heaven, O'brien, Evans, White, Meyer, Mathers and Moffatt2016). Along the same lines, secondary prevention, including early depressive symptoms detection, could be effectively targeted to older workers still employed, with particular reference to interventions implemented at the primary care level (Okereke et al., Reference Okereke, Lyness, Lotrich and Reynolds2013; Costantini et al., Reference Costantini, Pasquarella, Odone, Colucci, Costanza, Serafini, Aguglia, Belvederi Murri, Brakoulias, Amore, Ghaemi and Amerio2021).

About public policies, our data complement the accumulating evidence on the impact of pension reforms on health and mental health (Eibich, Reference Eibich2015; Carrino et al., Reference Carrino, Glaser and Avendano2020), suggesting that older workers should be granted greater flexibility in the timing of retirement in order to reduce their mental burden and avoid the development of severe depression. As many countries are implementing budget reductions to social welfare (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001), it is crucial to retrieve solid evidence on how different retirement policies might impact healthy ageing to balance money saved from cuts to pension systems with direct and indirect costs passed onto healthcare and social support systems. Although our review only focuses on mental health, the burden of mental health and, in particular, of depression is known to be associated with the burden of chronic physical conditions that significantly affect people's quality of later life, their demands for healthcare and other publicly funded services, generating significant societal consequences (Bech et al., Reference Bech, Christiansen, Khoman, Lauridsen and Weale2011; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Kuhn, Peterson, Rothman, Solórzano, Mathers and Dickson2011; Rechel et al., Reference Rechel, Grundy, Robine, Cylus, Mackenbach, Knai and Mckee2013).

Recommendations for future research

Concerning research, it clearly emerges from our analysis that, in order to reduce heterogeneity and accumulate solid evidence, shared methodological standards and definitions should be followed in the future. More extended longitudinal studies should be preferred so as to reduce inverse causality issues and might help disentangle and quantify the different components that mediate the effects of retirement on the risk of depression and its determinants and monitor such association's temporal evolution. It would also be necessary to further differentiate between contextual and individual characteristics to adapt coping strategies at the public health and clinical levels. Special attention should be paid to health inequalities to investigate better socioeconomic status indicators role in the relationship between retirement and health (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Boyce, Chesney, Cohen, Folkman, Kahn and Syme1994) and address the impact of specific policies focusing on health promotion for disadvantaged groups (Rechel et al., Reference Rechel, Grundy, Robine, Cylus, Mackenbach, Knai and Mckee2013). Stratifying results by job and retirement type and by socioeconomic status might be helpful to fill the gaps in current literature.

Conclusions

As a matter of fact, despite current trends in extending working lives, life expectancy after regular retirement is projected to grow faster than increases in the pension age, reaching 20.3 years for men and 24.6 years for women in 2050 (OECD, 2011). Therefore, from a societal, welfare and public health perspective, it is essential to invest in ‘third age’ health and wellbeing (Crimmins, Reference Crimmins2015). In a progressively ageing society, strengthened efforts are needed to make health interests count in welfare and pension policies and promote health protection after retirement (Moen, Reference Moen1996). We call for a coordinated advocacy action to identify retirement as a gateway for healthy lifestyles and an entry point for mental health prevention. Multidisciplinary collaborations between social sciences, public and community health, preventive medicine and psychiatry could be fruitfully put in place to generate much-needed evidence on the determinants, mediators and effect modifiers of the association between retirement and depression, as well as to design preventive interventions targeting older workers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000627

Data

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgements

For his conceptual insights and helpful discussion, we especially would like to thank the former Minister of Labour and social security, Professor Tiziano Treu.

Financial support

The present study is funded by: (i) Fondazione Cariplo, Grant: Aging and social research 2018: people, places and relations. Project: Pension reforms and spatial-temporal patterns in healthy ageing in Lombardy: quasi-natural experimental analysis of linked health and pension data in comparative Italian and European perspective (project n. 2018-0863); and (ii) the Italian Ministry of Health (project n. RF-2016-02364270).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required because this study retrieved and synthesised data from already published studies.