Introduction

The material culture of the Baltic towns in the heyday of the Hanse in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries has long been of interest to scholars from diverse backgrounds. In addition to a comprehensive treatment by historians, recent decades have seen a significant increase in archaeological investigations. Until recently, these have focused on the main urban centres of the region, thus offering a perspective on selected elements of the material culture, reflecting the level of life and living conditions in these towns (e.g. Rębkowski, Reference Rębkowski1995; LKSH, Reference Gläser1997, Reference Gläser1999, Reference Gläser2001, Reference Gläser2004, Reference Gläser2006, Reference Gläser2008; Gaimster, Reference Gaimster1999; Russow, Reference Russow2006; Nawrolska, Reference Nawrolska2014; Ansorge & Rütz, Reference Ansorge and Rütz2016). These studies provide valuable insights into life in larger medieval Baltic towns, but the ‘silent majority’ of the small and only locally influential Baltic Sea towns was seen as of secondary importance, since they were largely beyond the mainstream of active political or economic life and, in most cases, did not even belong to the Hanse. Thanks to archaeological investigations conducted there, it is now possible to offer an overview of these smaller towns’ material culture. Similarities and differences between the major and minor Baltic urban centres can be identified, as well as the degree and character of participation of the latter in the urban culture of the region, including their role within the Hanseatic world. Although discussion of these aspects is nothing new in the literature, a renewed surge in publications over the last two decades (Gaimster, Reference Gaimster1999; Immonen, Reference Immonen2007; Jahnke, Reference Jahnke, Engberg, Jorgensen, Kieffer-Olsen, Madsen and Radtke2009; Mehler, Reference Mehler2009; Müller, Reference Müller, Falk, Müller and Schneider2014; Naum, Reference Naum2015) makes the subject topical.

Most importantly, such questions fit into the broader framework of studies concerning the culture and economy of medieval Europe. To a certain extent, it draws on the centre–periphery model proposed almost fifty years ago (Wallerstein, Reference Wallerstein1974; Braudel, Reference Braudel1992; Dygo, Reference Dygo and Gawlas2006: 122–23). Whereas the most important towns were certainly the central places, exerting a clear influence on their surroundings, the smaller towns have so far been considered either as entirely peripheral or as peripheries participating in commercial exchange (so-called ‘semi-peripheries’: Wallerstein, Reference Wallerstein1974: 14–130). Their role may have varied within the proposed model of economic relations (Dyer, Reference Dyer2003, Reference Dyer, Giles and Dyer2007). Despite the secondary status of individual towns in this group, assessing their role as a category may be crucial for the discussion of the cultural and economic relations around the Baltic Sea (Jahnke, Reference Jahnke, Engberg, Jorgensen, Kieffer-Olsen, Madsen and Radtke2009: 59).

A separate and equally important aspect in this line of research is the role played by the Hanse in shaping the material culture of the urban centres. The Hanse's status as a key factor in this regard, commonly assumed in older scholarship, has been questioned more recently (Suhonen, Reference Suhonen2001; Immonen, Reference Immonen2007; Jahnke, Reference Jahnke, Engberg, Jorgensen, Kieffer-Olsen, Madsen and Radtke2009; Pluskowski, Reference Pluskowski2013: 238–44; Müller, Reference Müller, Falk, Müller and Schneider2014). In archaeology, this assumption manifests itself in a tendency to uncritically label various facets of material culture as Hanseatic without carefully analysing the context of the finds, including their meaning within their cultural milieu and commercial exchange. In recent years, the definition of the Hanseatic character of the Baltic urban communities’ material culture came to a head, and a new trend developed, emphasizing the influence of the German diaspora as a more important driver (Naum, Reference Naum2015). Simultaneously, it opened up ways of addressing questions of migration and the colonial nature of the formation of these urban centres in the Middle Ages (Immonen, Reference Immonen2007: 730–31; North, Reference North2009: 40–63). This relatively recent thread within Baltic studies provides a new perspective regarding the meaning and specificity of particular elements of the region's material culture.

A further important issue, largely absent or perhaps simply overlooked in studies of the main Baltic urban centres, concerns the identification of the inhabitants of the smaller towns with the urban culture of the Baltic Sea basin sensu lato. The inhabitants of these smaller towns signalled their belonging to this culture and to the community of burghers by their ownership of certain things and following specific practices or customs (Naum, Reference Naum2015: 72–73). The cases discussed in here are intended to broaden the ongoing discussion by introducing the smaller towns that complemented the urban and commercial exchange network in the Baltic region and interpreting finds considered as indicators of the so-called Hanseatic or German culture. We shall consider their role in the assemblages from such small urban centres and, more broadly, address the question of the Hanseatic cultural impact on towns that did not belong to the Hanse but were under its influence.

The Small Towns of Pomerelia (Gdańsk Pomerania)

In Pomerelia, a region of Pomerania (also known as Gdańsk Pomerania) between the rivers Vistula and Łeba in northern Poland, eighteen late medieval small towns form the basis of this study (Figure 1). Their treatment as a coherent group is justified on several grounds. First, they were all founded within a short period between the 1340s and the end of the fourteenth century (Biskup, Reference Biskup1980: 405; Grzegorz, Reference Grzegorz and Nowak1988: 49–50, Reference Grzegorz2007: 120–25; Czaja, Reference Czaja, Nowak and Czaja2000: 45–65). Admittedly, there was an earlier urbanization episode in Pomerelia in the thirteenth century, but it did not survive the conquest by the Teutonic Order in the following century (Lalik, Reference Lalik1965). Second, the fact that the urban centres in question developed under similar political conditions is of equal importance. All were established by the Teutonic Knights under the Kulm Law (a constitution for a municipal form of government named after the town of Chełmno, Kulm in German) as part of the provincial organization of the State of the Teutonic Order. They functioned within this state until the mid-fifteenth century when, following a conflict between the burghers and the sovereign, the Thirteen Years' War broke out and led to the province's incorporation into the Kingdom of Poland in 1466.

Figure 1. Urban network in Pomerelia in the fifteenth century.

The small towns’ significant similarities in terms of administrative structure, population size, distribution, and layout constitute a third important factor. The minor towns formed a hinterland for the feudal sovereign and hence had no particularly developed autonomy or administration (Czaja, Reference Czaja1999: 14–18).Footnote 1 They were mostly populated by settlers from outside Pomerelia. The bulk of the townspeople were Low German-speakers, although no restrictions were put in place for non-Germans wanting to obtain citizenship. The origin of the settlers must have been diverse, but only for Nowe and Puck do we have historical records detailed enough to address this question. An analysis of the names of the settlers indicates that the majority came from Prussia proper, which was conquered and colonized by the Teutonic Knights in the thirteenth century, and from Pomerelia. Some also came from the Duchy of Pomerania, from Silesia, Bohemia, or the core German lands, mostly Saxony and Thuringia. A small subset of settlers bore Slavic names (Penners, Reference Penners1942: 125–35; Piskorski, Reference Piskorski, Manikowska, Bartoszewicz and Fałkowski2000).

The small towns, as a result of a deliberate policy of the Order, were small centres, occupying an area no larger than 6–10 hectares. They all had a regular, planned layout, as stipulated by the charters, with blocks of housing surrounding a rectangular market square in the centre. In each case, the population would not exceed 1500 inhabitants in the Middle Ages (Gierszewski, Reference Gierszewski1966: 12–23; Czaja, Reference Czaja, Nowak and Czaja2000: 54–57; Kardasz, Reference Kardasz and Starski2017: 79–80). In effect, they were of just local or, at best, regional significance and did not belong to the Hanse. Despite their small population and limited opportunities for economic development, these towns were mostly populated by crafters and functioned as local trade and production centres interacting mainly with the rural hinterlands and regional market. The smaller towns of Pomerelia entered the arena of history relatively late, when the economic network around the Baltic Sea was already developed and dominated by the Hanse (Dollinger, Reference Dollinger2012: 81–90). The latter's economic prosperity is attested by the capital town of Gdańsk, one of the leading centres of commerce and culture by the Baltic Sea, which had a beneficial influence on the smaller towns of the region (Gierszewski, Reference Gierszewski1966: 184).

Our assessment of the small towns' material culture is based only on some of the eighteen towns, as not all were excavated. After thirty years of excavation campaigns, the best examined and published are Chojnice, Lębork, and Puck. Primary sites, such as market squares and town halls, as well as more than ten municipal plots, the surroundings of churches, and fortifications, were investigated in each of these towns. Open-area excavations in advance of development have given archaeologists the opportunity to record these urban centres and incorporate them into the broader discussion concerning the material culture of the region. Important archaeological work was also conducted in Bytów, Człuchów, Debrzno, Gniew, and Skarszewy, while the remaining towns were not excavated, or serve here as a backdrop to the discussion (for further discussion and references, see Starski, Reference Starski2015a).

The Components of the Small Towns

The analysis of the small towns’ material culture is now possible on the basis of building techniques, heating utensils, glazing, ceramics, glass vessels, and metal artefacts. The starting point is that the smaller Pomerelian towns were profoundly shaped by German colonization. The vast majority was established from scratch (in cruda radice) by newcomers from previously colonized areas (Biskup, Reference Biskup1980: 405; Grzegorz, Reference Grzegorz and Nowak1988: 49–50, Reference Grzegorz2007: 120–25). Even where a Slavic population has been confirmed as having participated in the urbanization process (Starski, Reference Starski2016a: 31), it does not alter the fact that the dominant group of burghers were German colonizers implementing customs and techniques from their own cultural repository, which in turn shaped specific ways of building or the repertoire of artefacts. These patterns were adapted to new conditions and under pressure of organizing and supplying the most basic needs of the emerging urban communities, while also shaping the local demand and supply dynamics.

This colonization is particularly visible in the building techniques employed and in the layout of urban plots. Most of the investigated towns’ plots followed known models, with their front used for residential purposes, their central section for production and its facilities, and their rear for sanitary and other production-related installations (Buśko, Reference Buśko1995: 347–48; Polak & Rębkowski, Reference Polak, Rębkowski and Rębkowski1996; Gupieniec, Reference Gupieniec1997). In the majority of towns, plots measured 3 × 7 Kulm rods (12.96 × 30.24 m), for example at Chojnice, Gniew, Lębork, Puck, and Tuchola, with a few exceptions where 4 × 6 rods (17.28 × 25.92 m) were used, for example at Bytów, Człuchów, and Debrzno (Betlejewska, Reference Betlejewska and Czaja2004). In the earliest stages of development, the plots were sometimes divided into smaller units (Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017a: 393–94).

The oldest houses (Figure 2A) were erected at the time of the towns’ foundation (mid-fourteenth century in most cases), and they were predominantly single-room, timber-framed, single-storey or multiple-storey structures measuring c. 4 × 5 or 5 × 6 m (Gupieniec, Reference Gupieniec, Rząska and Walenta2002; Walenta, Reference Walenta, Rząska and Walenta2002; Longa, Reference Longa2015: 53; Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017a: 413). In some cases, their timber cellars, an imported building element, were preserved. In Puck, we suppose that, after some two or three decades, these houses were no longer sufficient for the burghers and were enlarged by adding outhouses at the rear, narrower than the houses proper (Figure 2B). These timber-framed outhouses had no cellars but communicated with both the front house and the rear of the plot (Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017a: 409). Structures built with vertical posts and post-and-beam with wattlework in the rear parts of the urban plots have also been recorded (Longa, Reference Longa2015: 53; Blusiewicz, Reference Blusiewicz and Starski2017: 104–05). Another variant discovered in Puck, presumably introduced in the late fourteenth century, was a two-bay house with a masonry cellar erected in its rear bay (Figure 2 C–D). In this new type of burgher house, the residential quarters were moved to the second bay, the ground floor area covered c. 70 m2, and the whole building had multiple storeys built in wattle-and-daub or half-timbered (Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017a: 410–11). Other examples of two-bay timber-framed buildings with cellars located in the first bay and a rear annex have been recorded in Lębork and Puck. The evidence for brick-built dwellings in the smaller towns in the late Middle Ages is very scarce. The only known examples of such buildings, found in Lębork, are fragmentary and their size and layout cannot be reconstructed (Longa, Reference Longa2015: 49–64).

Figure 2. Reconstruction of house types erected in late medieval Puck. A: single-space house; B: house with an annex; C: house with a rear wing with stone cellar; D: remains of a stone cellar in a fifteenth-century house in the eastern part of a plot at The 1st of May Street in Puck.

The hitherto collected data on residential buildings indicate that in the first decades of a town's foundation several variants of small, usually timber-framed, houses were built to satisfy the basic needs of their residents. In subsequent years, as each centre developed, these needs would grow, resulting in the expansion of the houses and adoption of a model known in the Baltic cultural environment—the aisled house (Lippert, Reference Lippert1992: 187–202; Piekalski, Reference Piekalski2014: 132)—even if still within the same building technique (ordinary timber frame). Despite sparse evidence concerning the early stages of private brick dwellings in the smaller towns of Pomerelia, it seems that brick houses were rare and did not appear before the sixteenth century, although present in Gdańsk and Elbląg at the end of the fourteenth century (Kąsinowski, Reference Kąsinowski1997; Maciakowska, Reference Maciakowska2011: 117–22).

Heating systems are another aspect of technical adaptation known in the Baltic cultural environment used in late medieval houses of the smaller Pomerelian towns. In the kitchens, the typical arrangement was a brick floor under the hearth, over which cooking vessels would be hung, with smoke escaping via a wide hood to the chimney (Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017a: 397; Figure 3:1). The kitchen equipment, apart from pottery, included ceramic stands for spits (Figure 3:2) or iron grates. Several variants of heating devices were used: stoves made of pot tiles were most common (Figure 4:1). Although finds of such stoves do not appear in archaeological contexts before the late fourteenth century, the stoves themselves were most probably built closer to the mid-fourteenth century (Starski, Reference Starski2015b: 128–30, 212). The remains of a channel heating system recovered in Puck, consisting of a Gotland sandstone slab with a hole and several fragments of ceramic tiles with holes (Figure 3:2–6) constitute another peculiarity. Potentially, the device discovered at The 1st of May Street (Figure 3:3) was a hypocaust; but it cannot be excluded that it served a bathhouse erected on a private plot (Starski, Reference Starski, Dzik, Śnieżko and Starski2017b: 422–24). In general, however, fifteenth-century heating systems consisted of bowl tile stoves, built from a shorter form of vessel tiles (Figure 4:1). In the second half of that century, finds of panel tiles (Figure 4:1) are sporadically reported, attesting to the spread of innovative stove tile designs to the smaller Pomerelian towns (Starski, Reference Starski2015b: 135, Reference Starski2016a: 175–78). The oldest stove tiles with gothic ornamentation dated to the late fifteenth century have so far only been recovered in Puck, while large assemblages of such finds come from contexts dated to the second quarter of the sixteenth century in multiple urban centres. The decoration of these tiles adapted Renaissance ideas in the form of personifications of the senses, courtly scenes, and depictions of rulers (Figure 4:2–7).

Figure 3. Finds associated with heating of interiors and kitchens in burgher houses in Puck. 1: floor of a kitchen hearth; 2: base for a spit; 3–5: ceramic floor tiles with openings used in a hypocaust interior heating system; 6: cover for tiles.

Figure 4. Classification of tiles used in late medieval Puck (1) and selected Renaissance stove tiles from Puck (2–4) and Debrzno (5–7), second quarter of the sixteenth century.

Much less is known about the houses’ furnishings. This must have included various kinds of furniture, but their elements only survive in fragments, such as single and dispersed finds of joinery and fittings. Door or window fittings are known from hinges and staples, while keys and padlocks represent methods of locking them (Miścicki, Reference Miścicki and Starski2017: 194–202). Glazing in houses has not been recorded for the earliest stage of the towns. It was present in the town halls of Chojnice and Puck, but not before the early fifteenth century (Walenta, Reference Walenta2000; Starski, Reference Starski2015b: 150), and fragmented mountings and single windowpanes found on plots adjoining the market square there and in other towns indicate that glazing gradually spread during the fifteenth century.

Important insights into living conditions are offered by the rich repertoire of household items. This assortment can be considered comparable to that recovered in many urban centres of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, showing technical and stylistic adaptations (Enzenberger, Reference Enzenberger2007: 79–81; Wywrot-Wyszkowska, Reference Wywrot-Wyszkowska2019: 215–33). This is especially pronounced in the dominant use of wood as a material for various vessels and other items. Metal artefacts, mostly tools, but also fittings, elements of clothing, and militaria, also exhibit a diversity of forms (Miścicki, Reference Miścicki and Starski2017: 202–26). They indicate that local craftsmanship was highly accomplished (a less probable but possible scenario would include the import of goods from major trade centres to the smaller towns). Textile and leather goods were equally widely used but were only found in some plots and public spaces. They include footwear, belts, gloves, and probably also other elements of outer clothing (Wiklak, Reference Wiklak1993; Blusiewicz, Reference Blusiewicz and Starski2017).

An important part of the household consisted of various kinds of vessels, with the pottery in common use playing a crucial role in socio-cultural processes (Rębkowski, Reference Rębkowski1995: 77–85). In all of the investigated towns, the dominant types were flat-based vessels fired in a reducing atmosphere; they comprise mostly pots, followed by bowls, jugs, lids, mugs, and pans (Walenta, Reference Walenta, Rząska and Walenta2002: 43–45; Starski, Reference Starski2009, Reference Starski2016a) (Figure 5). Their quality is comparable to that of the major towns of the region, especially Gdańsk and Elbląg (Trzeciecka & Trzeciecki, Reference Trzeciecka, Trzeciecki and Gołembnik2002; Marcinkowski, Reference Marcinkowski2006; Nawrolska, Reference Nawrolska2014: 107–10). The predominance of grey ware was a result of the influx of foreign potters, who came to the newly founded towns as settlers, developed this new style, and found commercial outlets among other newcomers. Only in Puck does the situation appear more nuanced. The available data suggest two currents in the development of urban pottery. There, and possibly also in Gniew, native Kashubian (a Slavic group in eastern Pomerelia) potters made up about thirty per cent of the production and operated alongside the newcomers and continued to produce traditional wares (Figure 5 and 6A). The latter derived from techniques developed in local pottery near the end of the early Middle Ages (such as stone grit inclusions in the fabric and type of ornamentation). However, local potters would gradually introduce innovations to their own techniques and align their products on foreign examples by the late fourteenth century (Starski, Reference Starski2016a: 211–13). In the other emerging Pomerelian towns, the share of traditional wares was so marginal (no more than five per cent; see Table 1) that it should be interpreted as an influx of pottery from outside the urban context rather than the product of urban potters supplying the townspeople (Walenta, Reference Walenta, Rząska and Walenta2002: 43–45; Starski, Reference Starski2016b: 241). In addition to the dominant grey ware, a marginal part of the pottery recovered in all the investigated towns consisted of ceramics fired in an oxidizing atmosphere (Table 1).

Figure 5. Classification of ceramic vessel types used in late medieval Puck.

Figure 6. A: Assortment of ceramic vessels from Puck, second half of the fourteenth century. B: Set of stoneware jugs from the latrine in Lębork, first half of the fifteenth century.

Table 1. Distribution of local and imported ceramics in the small towns of Pomerelia compared to the major trading centre of Gdansk from the second half of the fourteenth century to the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Against the backdrop of local pottery production, the finds from the smaller towns also suggest that vessels from production centres participating in trade around the Baltic Sea were also imported (Gaimster, Reference Gaimster1999). Most notable is stoneware, attested in all our small towns, albeit never in a large percentage (Table 1; Starski, Reference Starski, Nawrolska, Paner, Piekalski and Trawicka2016c: 155–59). The most common were Siegburg jugs, but several Waldenburg or Lower-Saxonian vessels are also reported (Figures 5 and 6B). In addition to these foreign products, single glazed vessels were also found, but it has proved impossible to connect them to specific production centres (Figure 5); they may be linked to the Frysian–Danish–Lower-German circle (Starski, Reference Starski, Nawrolska, Paner, Piekalski and Trawicka2016c: 160–61). No trace of Spanish Lustreware, known from Elbląg and Gdańsk, has been found (Nawrolska, Reference Nawrolska2014: 120–21).

Further changes among the vessels are related to the gradual transformations that took place towards the end of the late Middle Ages (Table 1). Firing in the oxidizing atmosphere and glazing became more popular at the time, but the percentage of such vessels differs between the pottery assemblages from particular towns. Whereas in Puck at the beginning of the sixteenth century this share amounted to some thirty per cent, it did not exceed ten per cent in Lębork or Chojnice (Walenta, Reference Walenta, Rząska and Walenta2002: 44; Starski, Reference Starski2016a: 198, Reference Starski2016b: 239–41). Despite these differences, their distribution may nevertheless be used to track cultural transformations in this period, traceable in all of the most important Baltic urban centres. The discovery of such wares in smaller Pomerelian towns suggests that changes affected towns of different categories to a comparable degree (Table 1).

Vessels made of other materials, especially metal and glass, are usually thought to be luxury items and indicators of their owners’ high material standing (Gołębiewski, Reference Gołębiewski1992: 471–80; Nawrolska, Reference Nawrolska2014: 123–24; Haggrén, Reference Haggrén, Helmig, Scholkmann and Untermann2002, Reference Haggrén, Hansen, Ashby and Baug2015: 336), although such interpretations are open to question (Nawrolska, Reference Nawrolska and Gläser2008: 259–60; Naum, Reference Naum2015: 77–80). Undoubtedly, they were more expensive than wooden vessels and most of the ceramic containers made locally. Finds from archaeological excavations in Puck, however, suggest that glass vessels were popular in this town since the late fourteenth century, despite their relatively low frequency (Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017c: 290–92). At least twelve urban plots (out of twenty-five) yielded artefacts that could be reconstructed as glass beakers. In most cases, they were tall flute beakers decorated with coiled prunts, but shorter vessels, decorated or not, were also popular (Figure 7). Some of these vessels are paralleled in Bohemia and northern Germany (Haggrén & Sedláčková, Reference Haggrén and Sedláčková2007), but several forms may be related to the hitherto poorly researched Pomerelian products that emerged during the fifteenth century (Gołębiewski, Reference Gołębiewski1992: 471–80; Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017c: 290–92). Outside Puck, finds of glassware were less numerous in the remaining minor Pomerelian towns, e.g. Chojnice and Lębork, which were slightly larger centres than medieval Puck. Perhaps the high percentage of glassware in the latter town may be linked to the proximity of Gdańsk and the accessibility of its market to the local merchants.

Figure 7. Classification and chronology of late medieval glass vessels from Puck.

The use of metalware is documented in written sources in the majority of the investigated towns. These sources mainly refer to households of the Teutonic Order. Finds recovered from municipal plots are quite scarce and consist mostly of tripod cauldrons or Hanseschale-type bowls (shallow chased bowls; Miścicki, Reference Miścicki and Starski2017: 210). The recent discovery in Puck of two tripod vessels and a bowl appears to be an exception (Figure 8). Such a find may suggest that the use of metal vessels became widespread in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the paucity of finds being attributed to the reuse of scrap metal.

Figure 8. Two sixteenth-century metal tripod vessels from Puck.

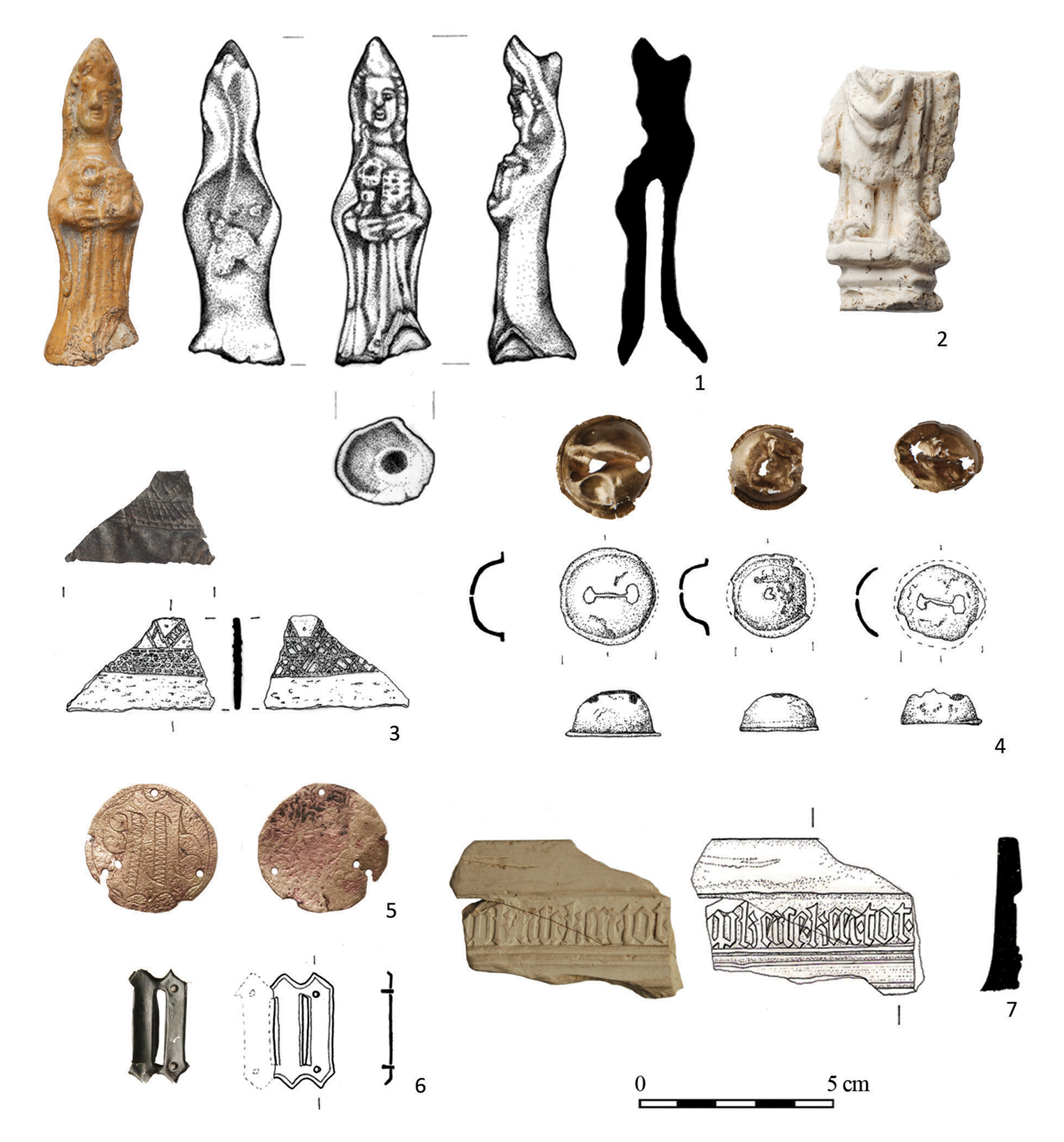

Among the remaining categories of artefacts used in the small towns of Pomerelia, mention must be made of devotional articles. Pilgrims’ canteens and figurines found in Lębork and Puck, figurines from Chojnice, Gniew, and Skarszewy, or less ceremonial miniature bells serve as examples (Figure 9). The marginal presence of pilgrims’ badges, which are known only from Lębork and Puck (Starski, Reference Starski and Starski2017d: 495) is notable. Many factors may have contributed to their quasi-absence, including the intensity of archaeological investigations, but it remains that there is a noticeable difference in the frequency of pilgrims’ badges between the larger and smaller towns in the region (Paner, Reference Paner2016).

Figure 9. Selected late medieval finds related to religious cult. 1–2: ceramic figurines; 3: pilgrims' badges; 4: miniature pilgrims' bells; 5–6: applique; 7: ceramic tiles.

The Nature of the Material Culture of the Small Towns

This review of the material culture from the smaller Pomerelian towns suggests that their living conditions did not differ significantly from those of the major urban centres of the region, at least in terms of household furnishings, everyday objects, elements of clothing, or decorative items. Local production was supplemented by a stable but small proportion of imported goods. Such a situation may be largely due to a question of scale: imported goods may have been typical but are less commonly found in the small towns than in the major towns, simply because the former were smaller. Certainly, the residents of these smaller towns had access to such cultural elements as building techniques or everyday objects and benefited from them, both in their local markets and as imported goods. Among the buildings and heating devices, very simple forms were used when the towns were just emerging, but the following decades saw progress in infrastructure and innovation (e.g. two-bay houses). The patterns in construction are therefore similar to those observed in the major towns of the region (Kąsinowski, Reference Kąsinowski1997; Maciakowska, Reference Maciakowska2011: 117–22), but the differences in the individual technical solutions applied—i.e. half-timbered wall rather than brick housing—are presumably owed to limited economic resources.

The repertoire of artefacts presented above suggests that, in general, a similar level of material culture was attained by the regions’ minor and major urban centres, even though studies devoted to spatial differences among major towns and their suburbs have so far not been undertaken. It is also worth highlighting the differences that we have observed: they are not so evident in the archaeological assemblages, but become more pronounced when the available written sources are taken into account. These discrepancies are apparent, for instance, in the degree of organization of craftsmanship and diversity within the guilds (Tandecki, Reference Tandecki, Nawrolski and Tandecki1997: 81–83). In the smaller towns, the first guilds were not established before the beginning of the fifteenth century and even then they tended to group several trades, while in larger centres the guild structure was already well developed and specialized (Bogucka, Reference Bogucka1962: 289–90; Tandecki, Reference Tandecki, Nawrolski and Tandecki1997). Even journeymen's associations were reportedly established there, which is entirely unheard of in the smaller towns of the period. The latter's poor engagement in the political activities of the urban communities of the State of the Teutonic Order constitutes a further discrepancy (Czaja, Reference Czaja1999: 14–18). Some differences have also been noted in financial mechanisms, namely in the loan market and feudal rent. This aspect has been studied in the case of the major Baltic towns (Kardasz, Reference Kardasz2013) but could only be outlined for the smaller towns (Samsonowicz, Reference Samsonowicz1960). Nevertheless, the fifteenth-century aldermen's register from Puck allows us to compare its loan market with that of the financial centres. According to Kardasz, the loan market played only a slight part in the town's economy, and even when the burghers had to borrow, it would be a one-off episode involving insignificant sums. They would not take out loans to undertake major activities, unlike their counterparts in Gdańsk, Elbląg, or Tallinn (Kardasz, Reference Kardasz and Starski2017: 83–84).

The wealth and variety of the excavated artefacts is much more pronounced in the everyday sphere than in the structures beyond it (Braudel, Reference Braudel1992: 23–24). This, in turn, begs an important methodological question: do archaeological finds reflect the actual material culture or living conditions of a given community, and to what degree should we rely on the written sources for insight into economic matters? The necessity to compare and analyse different sets of data in a broader perspective is present in the research conducted so far (e.g. as in Gilchrist, Reference Gilchrist2012).

The use of goods, apart from their role in defining the repertoire available to a given household, also reflects the aspirations of at least some of the burghers from the smaller towns to express their living standards and material status through items of higher value. The goal was presumably to emphasize one's material position within the local community, but also to express one's adherence to the urban culture of the region or the material culture of the German diaspora around the Baltic Sea (Naum, Reference Naum2015). To what extent this was a sign of cultural and economic integration within the larger urban centres and the Baltic market remains unknown. Such an integration took place in the State of the Teutonic Order and, in the course of the fifteenth century, led to the development not only of the urban network, but also of a society tightly bound with the Baltic urban culture (Pluskowski, Reference Pluskowski2013: 232–45).

As for the participation of the smaller towns’ communities in the urban culture of the region and the wider Hanseatic culture, the observations made above lend weight to the view that the burghers of the small towns aspired to belong to the urban culture of the German diaspora rather than to identify themselves with the culture of the Hanse. The latter's role, if any, was of secondary importance and it was not a significant factor influencing the material culture of the small towns of Pomerelia, as several studies have shown (Immonen, Reference Immonen2007: 728–30; Jahnke, Reference Jahnke, Engberg, Jorgensen, Kieffer-Olsen, Madsen and Radtke2009: 59–60). This is exacerbated by the difficulty of convincingly attributing a Hanseatic character to any particular component of their material culture, while not contradicting the conclusions of these studies that see the Hanse as a ‘culture carrier’ (Kulturträger: Müller, Reference Müller, Falk, Müller and Schneider2014) of broader processes of cultural change around the Baltic Sea. This influence was indirect, whereas more important indicators of cultural change came from the German urban community (Naum, Reference Naum2015: 77–79). The latter is particularly clear in the smaller towns: they did not belong to the Hanse community and its politics were most probably foreign to their residents. Therefore, if we identify common components in the material culture of the small towns, it is likely to be due to the presence of these artefacts in the major Baltic towns. Their use in smaller towns stemmed presumably from regional relations, such as trade, but also from mimicking the culture of the burghers of the larger urban centres. Thus, the phenomenon is connected to the influence exerted on the smaller towns by the German diaspora concentrated in the larger ones. Another thread—participation in the urban culture as a way to emphasize one's status and identity—is also crucial for an accurate evaluation of the situation. It could have been an even more important motivation for the inhabitants of the smaller towns than marking their belonging to the German diaspora.

Conclusions

The participation of the inhabitants of the small towns in the Baltic urban culture sensu lato may be summarized as follows. First and foremost, the smaller towns were of secondary importance in the creation of commercial and cultural exchange; they were no more (and no less) than the receivers of cultural trends and goods disseminated from the main centres to the provincial ones. They remained permanently connected to the major towns of the region, serving as a hinterland tightly cooperating with the centre and thus by no means peripheral. Consumers from these towns increased demand for particular goods distributed by the main trade centres, hence these urban communities partook in permanent commercial exchange. In effect, as a collective category, the smaller towns of Pomerelia should be considered semi-peripheral structures.

In this context, it is worth noting the differences, even if still somewhat unclear, regarding the way in which particular smaller Pomerelian towns participated in commercial exchange and adapted the urban culture. Some of these towns, such as Puck, Lębork, and most probably also Chojnice, exhibit similarities with the main urban centres of the region in terms of the proportion of imported vessels and building techniques. Yet, preliminary data obtained from other towns tell a different story; indeed, centres including Bytów, Człuchów, Debrzno, or Skarszewy show fewer traces of processes analogous to the main towns. As for sites such as Nowe, Starogard Gdański, Świecie, and Tczew, the lack of representative data precludes any definitive conclusions.

Bearing these caveats in mind, we may nevertheless hypothesize that some of the investigated centres were significantly more engaged in commercial exchange than others, owing to their proximity, coastal location, access to trade routes (including by river), and economic connections with the larger towns. This would make them appear less semi-peripheral and more like satellites connected to a centre. Such an interpretation is suggested not only by their status and aspirations to participate in commercial exchange, but also by Gdańsk's influence on its hinterland, including the smaller centres of the region. This hypothesis requires further research, and especially more data from other centres potentially belonging to the same category (e.g. Tczew or Starogard Gdański, both close to Gdańsk). Such a perspective sees the role of the smaller towns, or at least some of them, as a collective force shaping the cultural and economic relations around the Baltic Sea, with implications for the interpretation of the impact of the main towns and their burghers, whose active management of commercial relations would spread cultural patterns and influence the cultural identity of their hinterland.

The smaller Baltic towns, hitherto overlooked by mainstream scholarship, are seen as important participants in cultural transformations, despite their secondary role in the main currents of commercial exchange. They were stakeholders in this exchange and their status may display different features in different coastal regions of the Baltic Sea, depending on their local specificity. Hence, while many questions and uncertainties remain regarding their role in the late medieval Baltic world, their investigation opens promising avenues for the study of this category of urban centre.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2021.47.

Acknowledgments

This article is a result of the National Science Centre project entitled ‘Material Culture of Late-medieval Puck: Archaeological Portrait of Small Township on the Southern Coast of the Baltic Sea’ (no. 2013/09/D/HS3/04468). I am grateful to M. Talaga for the initial translation of this article.