The risk of psychosis is almost threefold for people with a background of childhood trauma (CT) [Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster and Viechtbauer1]. About 26% to 34% of the people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder have experienced CT [Reference Bonoldi, Simeone, Rocchetti, Codjoe, Rossi and Gambi2] that commonly includes sexual abuse [3,4], emotional abuse [5–Reference Morrison and Petersen8] and physical abuse [Reference Arseneault, Cannon, Fisher, Polanczyk, Moffitt and Caspi9]. CT is associated with frequency and severity of positive symptoms [10–Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan and Sellwood12] and with a ten-fold increase in symptom related distress [Reference Bak, Krabbendam, Janssen, Graaf, Vollebergh and Os13]. Moreover, it has been found to predict transition to psychosis in high risk samples [Reference Thompson, Nelson, Yuen, Lin, Amminger and McGorry14]. The increasingly clear evidence for a causal role of CT in the development of psychosis has begun to inspire research on the putative mediating mechanisms. Knowing these mechanisms is not only crucial to a comprehensive understanding of how psychosis develops, it can also help us to intervene earlier and more effectively.

Several studies have found negative affect, such as anxiety and depression, to link different types of trauma to positive symptoms [4,15–Reference Marwaha and Bebbington17]. It seems intuitive to assume that persistent negative affect might result from difficulties in emotion regulation (ER), which has been defined as the “processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one's goals.” [Reference Thompson18]. Building on this definition and synthesizing established ER theories [Reference Gross19], Berking and colleagues [Reference Berking, Wupperman, Reichardt, Pejic, Dippel and Znoj20] conceptualized adaptive ER as the ability to consciously process emotions, to support oneself in emotionally distressing situations, to actively modify negative emotions, to accept and tolerate emotions and to confront emotionally distressing situations in order to attain important goals.

Developmental and attachment theories point to various mechanisms underlying the development of ER, including observational learning, modeling and social referencing [Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson21], parenting style [Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad22] and attachment relationships [Reference Harder23]. For instance, parental punishment or neglect of a child's emotional displays have been linked to maladaptive ER [Reference Waller, Corstorphine and Mountford24]. Prospective studies show that early attachment predicts effective regulation strategies [Reference Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg and Lukon25] and CT has been found to fundamentally disrupt attachment to the maltreating caregiver [Reference Davies and Cummings26]. Unsurprisingly, thus, there is a bulk of research showing that CT compromises an individual's ability to regulate emotions effectively [27,28]. However, the causal inferences of these findings are limited due to the cross-sectional designs used.

Psychosis has repeatedly been found related to difficulties in ER [Reference Khoury and Lecomte29]. “Several studies have found psychosis to be associated with difficulties in being aware of [30,31], understanding, tolerating and accepting one's emotions [32–Reference Perry, Henry, Nangle and Grisham34], with using less functional strategies, such as reappraising the situation in a functional manner [30,31,35,36] and with more avoidance or suppression of emotions [33,34]. Moreover, difficulties in ER have also been associated with increased frequency of symptoms as well as exacerbated symptom distress [29,37]. It is noteworthy that these difficulties are also prevalent in people at risk of psychosis, who have found to be characterized by lower emotion awareness [38,39], less use of reappraisal strategies [39,40] and more suppression of emotions [Reference Kimhy, Gill, Brucato, Vakhrusheva, Arndt and Gross39]. This indicates that difficulties in ER seem to precede the disorder and might contribute to its development. However, only few studies have looked into the temporal relationship between ER and psychosis. A small community based study found maladaptive ER to prospectively predict psychotic symptoms from baseline to a 1-month follow-up assessment [Reference Westermann, Boden, Gross and Lincoln36]. Moreover, ER-skills have been found to predict increases in subjective distress and psychotic symptoms following a stressor in individuals with psychosis [Reference Lincoln, Hartmann, Köther and Moritz41]. Thus, there is preliminary evidence for a causal role of ER in the development of psychosis, but longitudinal studies are needed to further corroborate the postulated causal direction.

To sum up: As CT appears to have a significant influence on ER and difficulties in ER are evidently related to psychosis it seems reasonable to postulate that the ability to effectively regulate emotions could at least partially explain the relationship between CT and psychosis, especially as ER has been shown to mediate the association between CT and other psychopathologies (e.g. eating disorder [Reference Racine and Wildes42] and depression [Reference O’Mahen, Karl, Moberly and Fedock43]). Using a longitudinal design with four assessment time-points we hypothesized that (1) CT will significantly predict ER and psychotic experiences (defined as frequency of positive symptoms and related distress), (2) that the inability to regulate emotions at one time-point will predict psychotic experiences at the following time-point, (3) and that the relationship between CT and psychotic experiences will be at least partially mediated by ER.

1. Method

1.1. Participants and procedure

To enable an interpretation of the findings free of issues inherent to clinical populations (e.g. small samples, medication effects) the data for this study was collected in a community sample that covered the continuum of psychotic experiences including those that would be considered clinically relevant. Moreover, the sample was recruited from three different continents to increase the generalizability of findings beyond the western societies.

Participants from Germany, Indonesia, and the United States were requested to complete a 30-minute online survey anonymously (T0). Subsequently, they were invited via e-mail to complete a follow-up survey after 4 (T1), 8 (T2), and 12 months (T3). The follow-up surveys were protected by password to ensure that only participants who completed the baseline survey at T0 received the invitation for further participation. Recruitment was conducted through Crowdflower and other websites (e.g. internet forums and social networking websites). Crowdflower is a crowdsourcing Internet marketplace, similar to Amazon MTurk, on which people complete paid jobs. Participants recruited from Crowdflower received 0.50 US$ for completing the baseline survey analog to the median hourly wage in Amazon MTurk [Reference Buhrmester, Kwang and Gosling44]. In order to motivate participants to complete the follow-up surveys, the payment increased with each survey (T1, 0.60 US$; T2, 0.80 US$; T3, 1.00 US$). Participants recruited from other websites were not given compensation for reasons of data security. Participants had to be at least 18 years old and provide written informed consent before entering the study. This study received ethical approval from the ethical commission of the German Psychological Society (DGPs, TL062014_2).

There were 2501 completed baseline survey entries of which 151 were excluded due to duplicate entries (n = 98), longstring (i.e. providing the same answer consecutively for 50 items, n = 46 [Reference Johnson45]), and inconsistent answers (n = 7). The baseline sample thus consisted of 2350 participants of whom 720 completed the English, 786 the German and 844 the Indonesian version of the survey. Of those participants, 432 completed first the follow-up (response rate = 18.4%), 300 completed the second follow-up (response rate = 12.8%), 256 completed the third follow-up (response rate = 10.9%) and 139 completed all follow-ups (response rate = 5.9%). A detailed participant flowchart following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guideline is available in Supplementary Fig. 1.

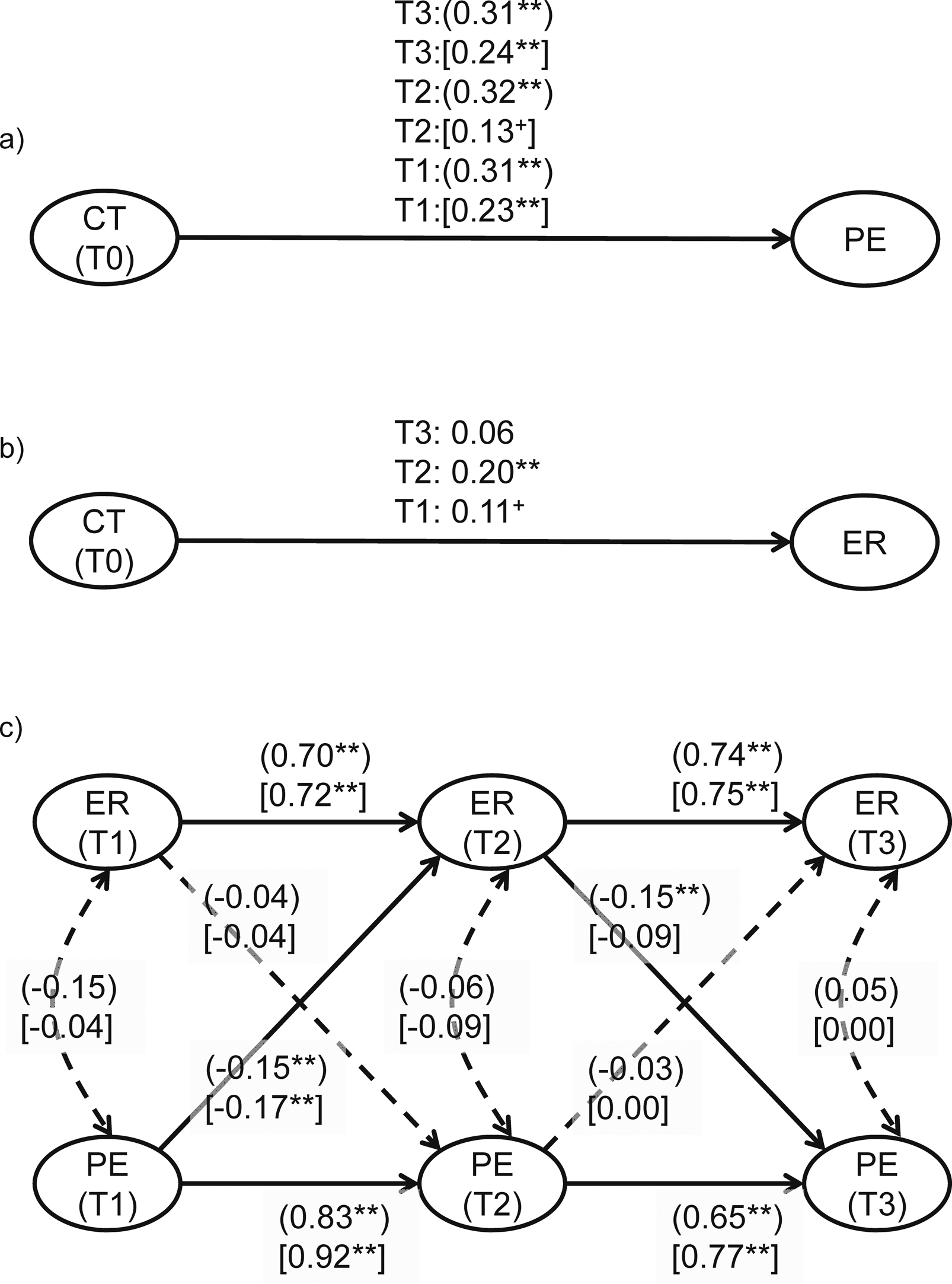

Fig. 1 Prospective association of childhood trauma, emotion regulation, and psychotic experiences. Note. (distress); [frequencies]; path coefficients are completely standardized; +P < .10, *P < .05, **P < .001. Dotted lines indicate insignificant paths. CT: childhood trauma; ER: emotion regulation; PE: psychotic experiences; T0: baseline; T1: month 4; T2: month 8; T3: month 12.

There were 2501 completed baseline survey entries of which 151 were excluded due to duplicate entries (n = 98), longstring (i.e. providing the same answer consecutively for 50 items, n = 46 [Reference Johnson45]), and inconsistent answers (n = 7). The baseline sample thus consisted of 2350 participants of whom 720 completed the English, 786 the German and 844 the Indonesian version of the survey. Of those participants, 432 completed first follow-up (response rate = 18.4%), 300 completed the second follow-up (response rate = 12.8%), 256 completed the third follow-up (response rate = 10.9%) and 139 completed all follow-ups (response rate = 5.9%). A detailed participant flowchart following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guideline is available in Supplementary Fig. 1.

In total, 562 participants completed at least one follow-up survey, fulfilled the inclusion criteria (i.e. complete entry, no longstring, and ID match) and were included in the analyses.

1.2. Measures

The back-translation procedure and cultural adaptation of measures was conducted with a native German or Indonesian.

1.2.1. Childhood trauma

Childhood trauma at T0 was assessed via a brief questionnaire adapted from “The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study” (NEMESIS) [Reference Janssen, Krabbendam, Bak, Hanssen, Vollebergh and de Graaf46]. The questionnaire assesses any kind of emotional, physical, psychological or sexual abuse before age 16 years according to the definition presented (e.g. sexual abuse, “How often were you sexually approached against your will? This means: were you ever touched sexually by anyone against your will or forced to touch anybody? Were you ever pressured into sexual contact against your will?”). Frequency of abuse is indicated on a six-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 6 = very often.

1.2.2. Psychotic experiences

Subthreshold and clinically relevant psychotic experiences at T1 through T3 were assessed with the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences (CAPE) [Reference Stefanis, Hanssen, Smirnis, Avramopoulos, Evdokimidis and Stefanis47], a 42-item self-report questionnaire. The CAPE assesses experiences related to positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and depression. The 20-item positive symptom subscale was used for the purpose of this study. It assesses a range of psychotic experiences, such as unusual or persecutory beliefs (e.g. “Do you ever feel as if you are under the control of some force or power other than yourself?”, “Have you ever felt that you were being persecuted in any way?”) or hallucinatory phenomena (e.g. “Have your thoughts ever been so vivid that you were worried other people would hear them?”, “Do you ever hear voices when you are alone?”) in the past four weeks on both a frequency scale (ranging from 1 = never to 4 = nearly always) and a distress scale (i.e. “Please indicate how distressed you are by this experience”; ranging from 1 = not distressed, 4 = very distressed). Previous studies have demonstrated good convergent and discriminative validity [Reference Hanssen, Peeters, Krabbendam, Radstake, Verdoux and van Os48] and the positive symptom subscale has good retest reliability (r = 0.63) [Reference Konings, Bak, Hanssen, van Os and Krabbendam49].

1.2.3. Emotion regulation

Functional ER-skills at T1 through T3 were assessed with the Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ) [Reference Berking and Znoj50] derived from the theoretical conceptualization by Berking et al. [Reference Berking, Wupperman, Reichardt, Pejic, Dippel and Znoj20]. The ERSQ is a 27-item self-report measure that assesses the application of ER-skills during the previous week on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 5 = almost always). It contains nine scales that correspond to the following nine skills: (a) consciously process emotions/be aware of emotions, (b) identify and label emotions, (c) interpret emotion-related body sensations correctly, (d) understand the prompts of emotions, (e) support oneself in emotionally distressing situations, (f) actively modify negative emotions in order to feel better, (g) accept emotions, (h) be resilient to/tolerate negative emotions, and (i) confront emotionally distressing situations in order to attain important goals. Both the total score and the subscales of the ERSQ show good internal consistencies (Cronbach's α = 0.90, and 0.68–0.81, respectively) and adequate retest-reliability (r tt = 0.75 and 0.48–0.74, respectively). All scales have demonstrated convergent and discriminate validity, including strong positive correlations with constructs related to ER [Reference Berking and Znoj50].

1.2.4. Substance use

Use of alcohol, cannabis and other substances was measured with self-report items based on the L section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview version 1.1 [Reference Smeets and Dingemans51] using a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (nearly every day).

1.3. Analyses

All analyses were conducted with structural equation modeling (SEM) using the sem function in lavaan ver. 0.5–20 [Reference Rosseel52] in R, version 3.2.3. Reported path coefficients are completely standardized. Reported overall total effect, overall direct effect, and overall indirect effect coefficients are unstandardized. The following indices and cut-off criteria were used to assess the fit between hypothesized models and the data: CFI ≥ 0.90, SRMR ≤ 0.08 [Reference Hu and Bentler53]; RMSEA ≤ 0.08 [Reference MacCallum, Browne and Sugawara54]. Maximum likelihood procedure with robust standard errors and a scaled test statistic, asymptotically equaling Yuan–Bentler test statistic, was used to correct for non-normal distribution. As we found that the frequency of psychotic experiences across measurement points was not missing completely at random (MCAR; χ 2(16) = 101.73, P < .001), subsequent analyses used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) with a missing at random (MAR) assumption. Variable inter-correlations and missing status are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

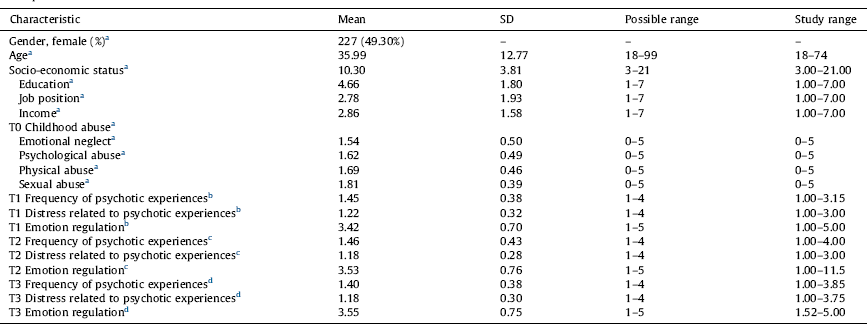

Table 1 Participants’ characteristics.

a n = 562.

b n = 432.

c n = 300.

d n = 256.

All analyses were conducted with structural equation modeling (SEM) using the sem function in lavaan ver. 0.5–20 [Reference Rosseel52] in R, version 3.2.3. Reported path coefficients are completely standardized. Reported overall total effect, overall direct effect, and overall indirect effect coefficients are unstandardized. The following indices and cut-off criteria were used to assess the fit between hypothesized models and the data: CFI ≥ 0.90, SRMR ≤ 0.08 [Reference Hu and Bentler53]; RMSEA ≤ 0.08 [Reference MacCallum, Browne and Sugawara54]. Maximum likelihood procedure with robust standard errors and a scaled test statistic, asymptotically equaling Yuan–Bentler test statistic, was used to correct for non-normal distribution. As we found that the frequency of psychotic experiences across measurement points was not missing completely at random (MCAR; χ 2(16) = 101.73, P < .001), subsequent analyses used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) with a missing at random (MAR) assumption. Variable inter-correlations and missing status are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Before testing the mediation hypotheses, we computed an autocorrelation model to test the precondition that CT, ER and psychotic experiences are correlated and within-construct autoregressive models to test the precondition that the values of variables at future time points depend at least in part on their respective values at earlier time points.

The mediation analysis was based on Baron and Kenny's [Reference Baron and Kenny55] principles for mediation and followed suggestions by Cole and Maxwell [Reference Cole and Maxwell56] for mediation testing in longitudinal designs. First, we examined the prospective paths from CT at T0 to frequency and distress of psychotic experiences at T1–T3 (path c), CT to ER at T1–T3 (path a), and ER at T1–T3 to frequency and distress of psychotic experiences at T1–T3 (path b) in separate models. Specifically, we examined path b with a cross-lagged panel model to take into account various sources of error such as the stability of the variables, cross-sectional associations, prior associations and the possibility of a reverse pathway.

According to Cole and Maxwell [Reference Cole and Maxwell56], path c (in this case the path from CT-PE to the final follow-up at T3) needs to be significant in order to conduct the longitudinal mediation analysis and compute the overall total, direct and indirect effect coefficients. These effect coefficients were considered significant if the bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence interval (BCa CI) did not include zero [Reference Cheung and Lau57]. ER was considered a significant mediator if the indirect effect coefficient was significant [Reference Mayer, Thoemmes, Rose, Steyer and West58].

2. Results

2.1. Participant characteristics

The participants were 24.31 years old on average and 49.3% were female. Moreover, 32.6% (n = 183) reported a life-time mental diagnosis, and 3.7% (n = 21) reported a current diagnosis of psychotic disorder. Slightly more than half (60.1%, n = 338) reported childhood abuse. Specifically, 45.9% (n = 258) of the participants reported to be victims of emotional neglect, 38.3% (n = 215) of psychological abuse, 31.1% (n = 175), and 18.5% (n = 104) of sexual abuse. Detailed participant characteristics are provided in Table 1.

2.2. Preliminary analyses

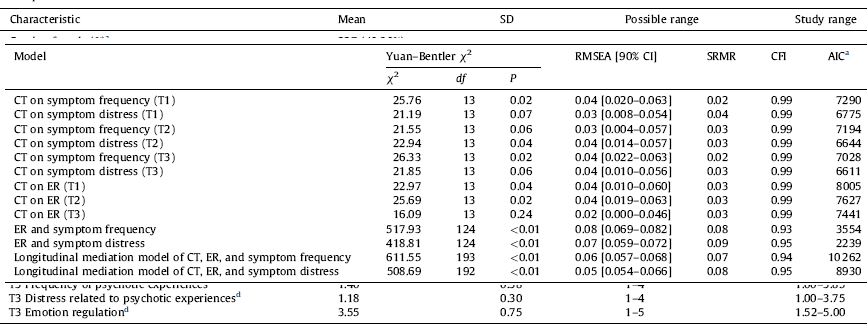

The autocorrelation model showed that CT, ER, and psychotic experiences (symptom frequency and distress) were significantly inter-correlated in the expected directions at all measurement time points. The within-construct longitudinal models showed that ER and psychotic experiences at a given assessment time-point predicted the respective variable at the next time-point, which demonstrates sufficient stability across time. Additionally, all fit indices were met, indicating that the parameters can be interpreted (see Table 2).

Table 2 Fit indices of the tested models.

Note. CT: childhood trauma; ER: emotion regulation; T0: baseline; T1: month 4; T2: month 8; T3: month 12; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR: Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; CFI: Comparative Fit Index; AIC: Akaike Information Criterion; 90%CI: 90% confidence interval.

a Rounded to the next integer.

2.3. Prospective association of childhood trauma, emotional regulation, and psychotic experiences

There were significant prospective paths from CT (as assessed at T0) to symptom frequency and distress at T3, and thus a significant path c (see Fig. 1a for details). Moreover, there was a significant prospective path from CT to ER at T2, and thus a significant path a (see Fig. 1b for details).

The prospective association between ER and psychotic experiences was tested with a cross lagged panel model (see Fig. 1c). Here we found a significant prospective path from ER at T2 to symptom distress at T3, but no significant prospective paths from ER to symptom frequency. Thus, the path b was only significant for symptom distress.

2.4. Longitudinal mediation analysis

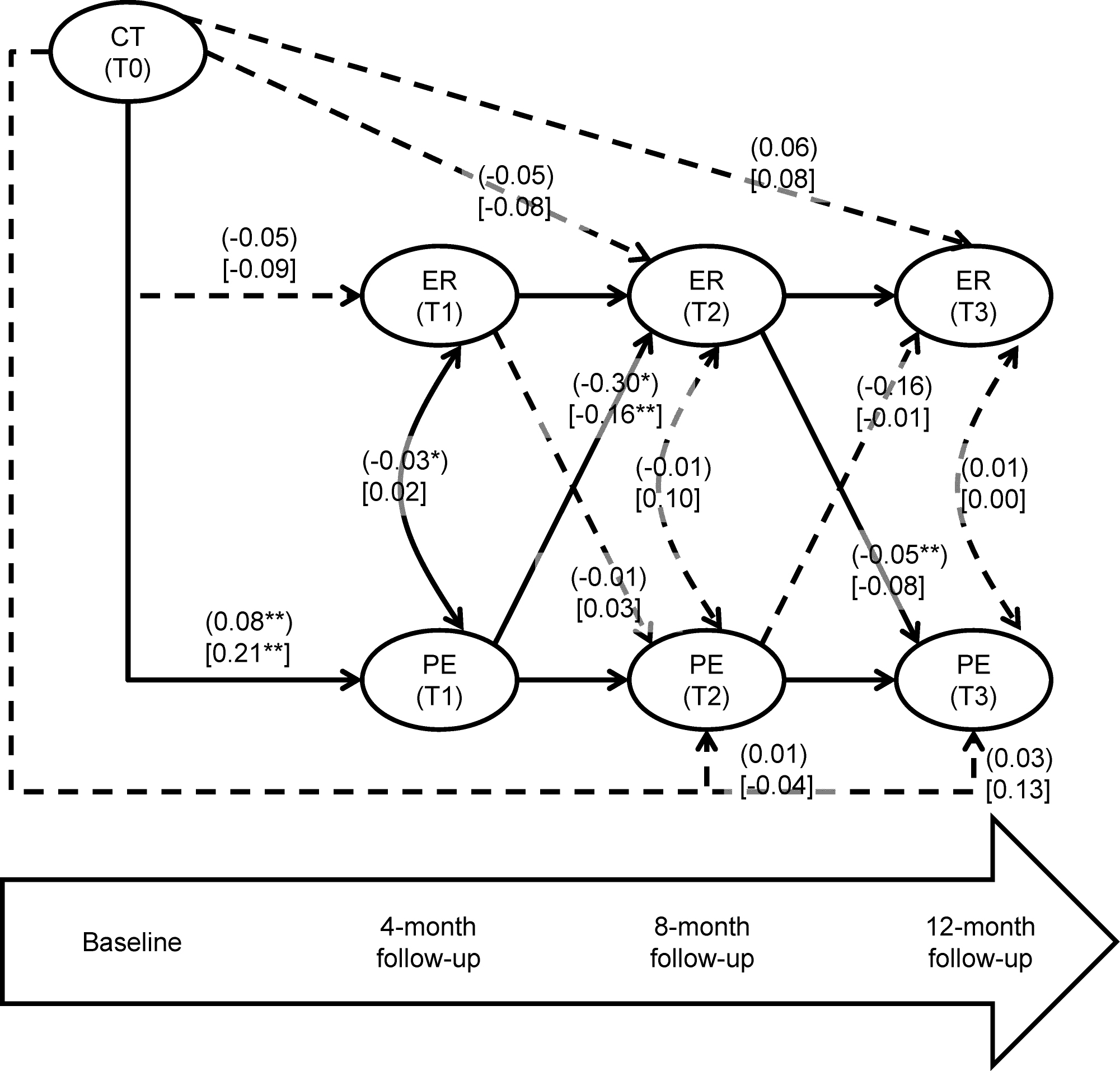

In the longitudinal mediation model (see Fig. 2), which included all time-points and the putative mediator ER, the previously significant path from CT to symptom distress (γ = 0.11, P = .12) at T3 was now non-significant. Furthermore, there was a significant path from ER (T2) to symptom distress (T3, β = −0.09, P < .01) indicating a possible mediation of ER in the relationship between CT and distress. Note, however, that there was also a significant path from both symptom frequency (β = −0.12, P < .05) and distress (β = −0.16, P < .01) at T1 to ER at T2, indicating that psychotic experiences do not just follow but also precede difficulties in ER.

Fig. 2 Longitudinal mediation analysis of childhood trauma, emotion regulation, and psychotic experiences. Note. (distress); [frequencies]; path coefficients are completely standardized; +P < .10, *P < .05, **P < .001. Dotted lines indicate non-significant paths CT: childhood trauma; ER: emotion regulation; PE: psychotic experiences; T0: baseline; T1: month 4; T2: month 8; T3: month 12.

Since the hypothesized paths from ER to symptom frequency were not significant, the overall total, direct and indirect effect was only computed for symptom distress. The overall total effect of CT on symptom distress at final follow up was significant at 0.0747 (95% BCa CI, 0.0311, 0.1184). This effect consisted of a significant overall direct effect of 0.0694 (95% BCa CI, 0.0269, 0.1119) and a significant overall indirect effect of 0.0053 (95% BCa CI, 0.0002, 0.0104). The mediation proportion [Reference Ditlevsen, Christensen, Lynch, Damsgaard and Keiding59] showed that ER mediated 7.1% of the overall total effect of CT on symptom distress.

2.5. Additional exploratory analyses

In order to explore whether the associations of interest differ across symptoms, we repeated the analyses using the hallucination and paranoia subscale of the CAPE [Reference Schlier, Jaya, Moritz and Lincoln60] as dependent variables. The results are presented in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 for hallucinations and paranoia, respectively. We found childhood trauma to predict both frequency and distress of hallucinations and paranoia over time. Moreover, ER predicted both frequency and distress of paranoia, but not of hallucinations. Consequently, we only conducted the longitudinal mediation analysis on paranoia. The results of this analysis are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. The overall total effect of CT on paranoia distress at final follow up was significant 0.130 (95% CI, 0.075, 0.186). This effect consists of a significant overall direct effect of 0.116 (95% CI, 0.062, 0.171) and a significant overall indirect effect of 0.014 (95% CI, 0.001, 0.027). The overall total effect of CT on paranoia frequency at final follow up was also significant at 0.109 (95% CI, 0.059, 0.159), which consists of a significant overall direct effect of 0.099 (95% CI, 0.049, 0.149) and a significant overall indirect effect of 0.010 (95% CI, 0.001, 0.020). Thus, ER was a significant partial mediator in the association between CT and paranoia frequency and distress.

In order to explore whether the associations of interest differ across symptoms, we repeated the analyses using the hallucination and paranoia subscale of the CAPE [Reference Schlier, Jaya, Moritz and Lincoln60] as dependent variables. The results are presented in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 for hallucinations and paranoia, respectively. We found childhood trauma to predict both frequency and distress of hallucinations and paranoia over time. Moreover, ER predicted both frequency and distress of paranoia, but not of hallucinations. Consequently, we only conducted the longitudinal mediation analysis on paranoia. The results of this analysis are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. The overall total effect of CT on paranoia distress at final follow up was significant 0.130 (95% CI, 0.075, 0.186). This effect consists of a significant overall direct effect of 0.116 (95% CI, 0.062, 0.171) and a significant overall indirect effect at 0.014 (95% CI, 0.001, 0.027). The overall total effect of CT on paranoia frequency at final follow up was also significant at 0.109 (95% CI, 0.059, 0.159), which consists of a significant overall direct effect of 0.099 (95% CI, 0.049, 0.149) and a significant overall indirect effect at 0.010 (95% CI, 0.001, 0.020). Thus, ER was a significant partial mediator in the association between CT and paranoia frequency and distress.

Furthermore, we investigated differences between countries in our variables of interest. We did not find significant mean differences between countries in regard to CT, ER, and symptom distress. However, we did find significant differences between countries in symptom frequency (F(2,429) = 14.60, P < 0.01), with post hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction indicating psychotic experiences to be significantly more frequent in participants from Indonesia (M = 1.60) than in those from Germany (M = 1.36) and the United States (M = 1.44).

Finally, in order to rule out that ER was merely a proxy for substance abuse, we analyzed correlations between ER and the use of alcohol, cannabis, and other substances, which were all found to be non-significant.

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary of findings and general discussion

This study tested for a significant association of CT and psychotic experiences, a predictive effect of ER on psychotic experiences and a mediating role of ER in the relationship of CT and psychotic experiences. As hypothesized, and in line with the extensive literature highlighting maltreatment as a major risk factor for later psychosis [Reference Arseneault, Cannon, Fisher, Polanczyk, Moffitt and Caspi9] we found CT to be significantly related to psychotic experiences. Confirming part of our second hypothesis, we found that the ability to regulate emotions significantly and prospectively predicted fluctuations in symptom distress over time. Thus, the fewer ER skills an individual endorsed at a given time-point, the higher the likelihood that this individual would be distressed by psychotic experiences at the next time-point. This finding adds to the preliminary evidence indicating a covariation of at risk-mental states and ER [38–Reference van der Velde, Opmeer, Liemburg, Bruggeman, Nieboer and Wunderink40], a causal influence of ER on psychotic symptoms and distress [36,41], and suggests that the ability to effectively regulate emotions is crucial to arrive at low levels of symptom distress.

Given the overwhelming evidence for affective pathways to psychosis [61,62], we were surprised by the absence of a significant path from ER to symptom frequency. Possibly, the mere presence of non-distressing low-threshold delusional beliefs or perceptual phenomenon as assessed in the frequency domain of the CAPE might not have sufficient pathological character to find significant associations with putative risk factors for psychosis. Psychotic symptom distress has been found to be a better discriminator between clinical and non-clinical samples than frequency [Reference Lincoln63] and to improve the prediction of high risk status relative to frequency of psychotic experiences on their own [Reference Kline, Thompson, Bussell, Pitts, Reeves and Schiffman64]. Thus, it appears to be a more valid indicator of relevant subclinical symptomatology. However, this assumption warrants further research that includes measures of clinical relevance (e.g. functioning).

Moreover, interestingly, our test of the “reverse causation model” revealed that symptom frequency and related distress at one time-point also significantly predicted an impaired ability to regulate emotions at the next time-point. This could be explicable by the fact that psychotic experiences demand attention, leaving less attentional capacity to deal with distressing emotions, an effortful process it itself. Moreover, people who are feeling distressed by psychotic symptoms are dealing with higher levels of negative affect that are more difficult to down-regulate (causing them to report less success in ER) than the milder levels of emotional distress people without disturbing psychotic experiences are faced with. The longitudinal pattern of associations speaks for reciprocal exacerbations of symptom distress and ER difficulties in which people appear to be getting caught up in a vicious circle of psychotic experiences, negative affect and difficulties in down-regulating negative emotions. This may explain symptom exacerbation over longer time-periods.

The significant overall indirect effect indicates that ER partially explains the link between CT and symptom distress. This has not been investigated in regard to psychosis so far and thus makes a novel contribution to the field. However, the mediating effect was only found for symptom distress, not for symptom frequency. Taken together with research showing that ER also mediates between CT and other affective disorders [Reference Carvalho Fernando, Beblo, Schlosser, Terfehr, Otte and Löwe65] one could speculate that ER may be more relevant to the affective symptomatology associated with psychosis than to the specific psychotic symptomatology as such. Thus, the specificity warrants further research. Moreover, the mediation was partial, explaining 7.1% of the total relationship between trauma and symptom distress. This indicates that other putative mediators should be considered, candidates being negative schema [15,66], social cognition (e.g. impaired theory of mind [67,68]), neurocognitive impairment [Reference Lysaker, Meyer, Evans and Marks69], substance abuse [Reference Mandavia, Robinson, Bradley, Ressler and Powers70], and ongoing social adversities [Reference Jaya and Lincoln71]. In addition to the reduced functional ER strategies as assessed in this study (e.g. acceptance, tolerance and clarity of emotions), increased dysfunctional ER strategies (e.g. rumination, suppression, or avoidance), might also contribute to mediating the relationship of CT and symptom distress, in particular because these types of ER have been found to be linked to CT [43,72] and to exacerbated symptom distress in psychosis [29,73,74]. Notably, the focus on functional rather than dysfunctional ER in our study might explain why we did not find a significant correlation between substance use and ER as has been found in other studies [Reference Mandavia, Robinson, Bradley, Ressler and Powers70].

Our additional analyses of the effects for paranoia and hallucinations suggest that although CT was linked to both paranoia and hallucinations the mediating role of ER may be specific to paranoia. However, the insignificant finding for hallucinations needs to be interpreted with caution because the hallucination subscale only has four items. Thus, the question of specificity warrants further research with more suitable measures for this purpose.

3.2. Limitations

The participants were drawn from a pool of people with access to the Internet. These participants tended to be highly educated and to have middle to low income. Similar sample characteristics have been reported by other researchers who used crowdsourcing websites for recruitment [Reference Shapiro, Chandler and Mueller75]. Due to the slightly reduced variability of the participants’ demographics, the strength of the observed relationships might have been underestimated. However, the sample was sufficiently heterogeneous in regard to the variables of interest: childhood trauma and psychotic experiences. Moreover, the inclusion of individuals from three countries adds to the representativeness of the sample.

Another limitation is that only 23% of the baseline-group participated in the follow-ups and only 5.9% of the initial sample completed all assessments. Although we used FIML procedure in all analyses to take into account the missing data, we cannot rule out that the high attrition rate influenced the results. The correlates of missing data reported in Supplementary Table 1 suggest that participants with more severe symptoms were more likely to miss follow-up assessments. Selective drop-out at the higher end of the symptom spectrum could have resulted in reduced variability and thus in attenuated effect sizes [Reference Terluin, de Boer and de Vet76].

Another limitation is that only 23% of the baseline-group participated in the follow-ups and only 5.9% of the initial sample completed all assessments. Although we used FIML procedure in all analyses to take into account the missing data, we cannot rule out that the high attrition rate influenced the results. The correlates of missing data reported in Supplementary Table 1 suggest that participants with more severe symptoms were more likely to miss follow-up assessments. Selective drop-out at the higher end of the symptom spectrum could have resulted in reduced variability and thus in attenuated effect sizes [Reference Terluin, de Boer and de Vet76].

Another issue is that the retrospective assessment of CT is prone to recall bias [Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Woodward77]. Similarly, the self-report diagnosis cannot be externally verified. However, the minimal reward for survey termination, the application of data verification procedures and the similarity of prevalence rates of life-time mental diagnosis (32.1%) to representative samples from epidemiological studies (e.g. 29.4% [Reference Kessler, Demler, Frank, Olfson, Pincus and Walters78]) speak for the validity of the data. Furthermore, the mean CAPE scores for frequency of positive symptoms across all assessment time-points are comparable to those found in a large data set of previously published data [Reference Schlier, Jaya, Moritz and Lincoln60]. People who reported no mental disorder in our study had a mean score of M = 1.44 (compared to M = 1.41 in other population samples [Reference Schlier, Jaya, Moritz and Lincoln60]) and those who reported a psychotic disorder had a mean value of M = 1.52 (compared to a mean value of M = 1.73 for participants with a psychotic disorder in other studies [Reference Schlier, Jaya, Moritz and Lincoln60]).

Moreover, our measure of ER assessed what the participant remembered to have done in response to emotions when they arose during the past week rather than assessing “online ER” (e.g. by using experience sampling [Reference Catterson, Eldesouky and John79] or online ER in a standardized paradigm [Reference Sheppes and Meiran80], which might have led to more variability in ER over time. Nevertheless, we found a sufficient variation in the use of ER strategies (with correlations between time-points of around 0.7, see Fig. 1c), which was similar to the stability found for psychotic experiences and can be considered sufficient to investigate whether the inability to regulate emotions at one time-point will predict psychotic experiences at the following time-point as hypothesized.

Lastly, the analytical strategy may have overestimated the stability of ER and symptom frequency and distress while underestimating cross-lagged effects [Reference Cole, Martin and Steiger81]. This is partly due to the shared method factor (i.e. psychotic experiences at all time-points were measured with the exact same items). However, we opted for this more conservative approach keeping the probability of type I error low because the study was not exploratory in nature.

3.3. Therapeutic implications

The results indicate that targeting ER in victims of childhood trauma and in those at risk of psychosis could be a promising way to interrupt the cascade of negative affect, psychotic experiences and distress. There are several approaches available that can be employed or used to inform novel interventions. For example, third-wave approaches, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [Reference Bach and Hayes82] and Emotion Focused Therapy (EFT) [Reference Greenberg83] aim at enhancing the ability to tolerate negative affective states and to accept the presence of difficult thoughts or feelings [83,84] and have shown promising effects in the treatment of psychosis [82,85]. Moreover, there are programs that focus solely on ER by training adaptive ER-skills such as acceptance, tolerance, reappraisal and problem solving [20,86] and these programs have been found to be promising in various inpatient populations [20,87]. These types of trainings could potentially be beneficial to reducing transition to psychosis – possibly as an add-on to existing approaches – especially if they are tailored to improve a person's individual profile of ER skills.

4. Conclusion

Researchers have worked toward identifying pathways from CT to psychosis [Reference Isvoranu, van Borkulo, Boyette, Wigman, Vinkers and Borsboom88] and have put forward the idea of an affective pathway linking trauma to psychosis by heightened emotional distress, anxiety and depression [16,17]. Our findings extend this line of research by pointing to the role of ER as a possible psychological mechanism involved in this process. Although this mechanism is unlikely to be specific to psychosis, the fact that difficulties in ER precede and follow from symptom distress render ER a promising target for interventions aimed at increasing well-being and preventing psychotic symptom exacerbation.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.12.010.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.