Introduction

People with schizophrenia frequently express the need to find a job or to be helped to keep a job [Reference Franck, Bon, Dekerle, Plasse, Massoubre and Pommier1]. Despite individual and collective beneficial effects [Reference Pachoud and Corbière2–Reference Silverstein and Bellack5], there are very few people with severe mental illness in general and schizophrenia especially in employment [Reference McGurk and Mueser6,Reference Marwaha, Johnson, Bebbington, Stafford, Angermeyer and Brugha7]. There are wide variations in reported employment rates in schizophrenia. Most recent European studies report employment rates for people with schizophrenia between 10 and 20% [Reference Marwaha, Johnson, Bebbington, Stafford, Angermeyer and Brugha7–Reference Bebbington, Angermeyer, Azorin, Brugha, Kilian and Johnson10]. People with severe mental illness are six to seven times more likely to be unemployed than people with no mental health problems [8].

For people with schizophrenia, obtaining and retaining employment translates into better social and family relationships, overall health, and self-esteem [Reference Cichocki, Arciszewska, Błądziński, Hat, Kalisz and Cechnicki11,Reference Bond, Resnick, Drake, Xie, McHugo and Bebout12], resulting in quality-of-life improvements. Employment supports the recovery process, which needs empowerment, a restored self-esteem, a positive social identity, and an improved quality of life [Reference McGurk, Mueser, DeRosa and Wolfe3–Reference Silverstein and Bellack5,Reference Anthony13–Reference Pańczak and Pietkiewicz16].

Despite these well-documented benefits, employment rate of people with schizophrenia remains quite low in France, and job opportunities are frequently located in sheltered employment (ShE) [Reference Pachoud, Llorca, Azorin, Dubertret, de Pierrefeu and Gaillard17]. ShE or workshop approach is called the traditional or “train and place” vocational rehabilitation [Reference Pachoud and Corbière2,Reference Pachoud, Llorca, Azorin, Dubertret, de Pierrefeu and Gaillard17,Reference de Pierrefeu and Charbonneau18] and has longer been the only alternative to unemployment for people with schizophrenia [Reference Reker, Eikelmann and Inhester19]. It offers to people a training during a long period of prevocational training, with a small proportion obtaining competitive employment. Another approach is the “place and train” approach, such as supported employment (SE) programs, in which employment specialists or “job coaches” help people obtain and then keep a competitive job as fast as possible with no requested training [Reference de Pierrefeu and Charbonneau18,Reference Modini, Tan, Brinchmann, Wang, Killackey and Glozier20]. The most effective vocational services are based on the “place and train” model, and even more precisely on the individual placement and support model, that allows to more than 50% of people with a severe mental illness to obtain a competitive employment after 6–18 months of individualized support [Reference Pachoud, Llorca, Azorin, Dubertret, de Pierrefeu and Gaillard17,Reference Lehman21,Reference Crowther, Marshall, Bond and Huxley22].

There are different outcomes that can constitute obstacles to employment in schizophrenia. Social, demographic, environmental, or even personal factors can partially explain the poor access and maintaining in employment of people with severe mental illness. Factors relating to the disease itself are mostly involved. Negative symptoms have a substantial adverse impact in both competitive employment and ShE [Reference Slade and Salkever23]. But it is widely acknowledged that cognitive impairments associated with schizophrenia are outcomes which most affect work access and maintaining [Reference McGurk, Mueser, DeRosa and Wolfe3].

Various domains of neurocognition assessed by individual tests are related to work functioning [Reference Lystad, Falkum, Haaland, Bull, Evensen and Bell24]. Level of cognitive functioning is a predictor of patients’ work outcomes [Reference McGurk, Mueser, Harvey, LaPuglia and Marder25]. Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia are unspecific and include deficits in attention, learning and memory, declarative and working memory, speed of processing, and executive functioning such as reasoning and problem-solving [Reference Kern, Glynn, Horan and Marder26,Reference Tan27]. Ninety percent of people with schizophrenia have clinically meaningful deficits in at least one cognitive domain, and 75% have deficits in at least two [Reference Gaudiano28]. Learning of new work tasks is affected by attention and memory impairments [Reference Tan27]. Executive dysfunction can lower the patient’s work functioning, resulting in a poorer work integration [Reference Tan27]. Executive functioning, verbal learning, attention, and psychomotor speed, as well as the severity of psychotic symptoms, are correlated with the needs of vocational rehabilitation [Reference McGurk, Mueser, Harvey, LaPuglia and Marder25]. Vocational rehabilitation appears to work by compensating for the effects of cognitive impairment and symptoms on work, according to a review of literature conducted by McGurk and Mueser [Reference McGurk and Mueser6].

Cognitive remediation (CR) is an evidence-based nonpharmacological treatment for the neurocognitive deficits frequently associated with severe mental illness [Reference Medalia and Choi29]. CR is most likely to impact functional outcomes when individuals are given opportunities to practice their cognitive skills and is more effective when integrated in psychosocial rehabilitation programs and connected to patient’s goals [Reference Kern, Glynn, Horan and Marder26,Reference Medalia and Choi29–Reference Medalia and Saperstein33]. In routine psychiatric practice, performing a neuropsychological assessment should be used systematically to clarify the project of care and rehabilitation of patients with schizophrenia. In addition, remediation should also be widely used therapeutically, and many psychiatric services have adopted it during the last years. CR associated with SE has demonstrated its cost-effectiveness compared to traditional vocational rehabilitation [Reference Yamaguchi, Sato, Horio, Yoshida, Shimodaira and Taneda34]. CR combined with SE or traditional vocational interventions appears to be more effective on work outcomes, such as work attendance, than SE only or other vocational interventions without CR [Reference McGurk, Mueser, DeRosa and Wolfe3,Reference Teixeira, Mueser, Rogers and McGurk35–Reference Ikebuchi, Sato, Yamaguchi, Shimodaira, Taneda and Hatsuse40]. It is particularly true for people with lower community functioning, as SE enhanced with CR improves their vocational outcomes, but this difference is not significant in higher-functioning participants’ groups [Reference Bell, Choi, Dyer and Wexler41]. Improvements in executive functioning and verbal memory could particularly predict improvements in daily functioning in schizophrenia [Reference Penadés, Catalán, Puig, Masana, Pujol and Navarro42].

Taking this into account, it is a major challenge for psychosocial rehabilitation in schizophrenia to reduce the impact of cognitive impairments on employment [Reference Franck37,Reference Norman, Lecomte, Addington and Anderson43]. There is an extensive literature about the benefits of CR on work integration, but less is known about this relationship in the French context. Different types of vocational programs coexist in France: SE, which is an evidence-based practice to help people get competitive employment, social firms or ShE, and hybrid vocational programs [Reference Pachoud and Corbière2]. Our study focuses on CR impacts in ShE. The expected benefits for participants are a better professional insertion and improvements in cognitive and social skills and functional outcomes.

Methods

RemedRehab was a multicentric randomized comparative open trial in parallel groups conducted in eight centers in France between 2013 and 2018. This project is part of a strong partnership between the CR network and the ShE network in France. Participants were recruited into ShE firms before their insertion in employment (preparation phase).

A preselection of study candidates based on the following criteria was made prior to inclusion: scheduled entry in ShE 4 months later, age, native language, diagnosis, no neurological disorders (stroke, cranial trauma, and neurodegenerative diseases), no addiction (except tobacco), IQ > 70 (evaluated with Raven’s progressive matrices), and no treatment by electroconvulsive therapy in the previous 6 months. We included patients with schizophrenia based on DSM-IV criteria, aged from 18 to 45 years, speaking and reading French, whose clinical state was stable and who must integrate ShE positions within 4 months after inclusion. They were randomly assigned to one of two groups: cognitive training (RECOS group) and Treatment As Usual (TAU group). Randomization was stratified by site. Each intervention (RECOS and TAU) was conducted during 3 months before integration in ShE (preparation period).

Three evaluations were conducted by psychologists specializing in neuropsychology at T1, T2, and T3. Blinded outcome assessments were conducted. Participants benefited from CR or TAU during the preparation period (T1–T2) prior to their entry in ShE (T2). They were reevaluated at integration in ShE (T2), and a third evaluation was conducted 6 months later (T3). Evaluations were similar at T1, T2, and T3.

The aim of the study was to compare the benefits of the RECOS CR program versus the TAU on access to employment and work attendance for people with schizophrenia, measured by the following ratio (R): number of hours worked on number of hours stipulated in the contract of employment in the 6 months following the entry into ShE.

Secondary outcomes were:

1. Comparative evolution of cognitive outcomes in the RECOS and TAU groups at baseline (T1), at integration in ShE (T2), and 6 months later (T3). Assessments of cognitive functions were based on standardized neuropsychological tests intended to assess impaired cognitive functions in schizophrenia:

1.1. Working memory: memory of figures (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition) [Reference Ryan, Lopez, Dorfman and Hersen44,Reference Benson, Hulac and Kranzler45];

1.2. Spatial memory (MEM IV) [Reference Ryan, Lopez, Dorfman and Hersen44];

1.3. Selective attention and processing speed: D2 [Reference Brickenkamp and Zillmer46]; Stroop [Reference Godefroy, Jeannerod, Allain and Le Gall47];

1.4. Verbal memory: RL/RI-16 items [Reference Van der Linden, Adam, Agniel and Baisset Mouly48]; RBMT [Reference Wilson, Cockburn, Baddeley and Hiorns49];

1.5. Verbal fluency: fluence [Reference Cardebat, Doyon, Puel, Goulet and Joanette50];

1.6. Memory and visual–spatial attention: BVMT [Reference Benedict, Schretlen, Groninger, Dobraski and Shpritz51];

1.7. Reasoning: matrices [Reference Benson, Hulac and Kranzler45];

2. Comparative evolution of the clinical and functional outcomes in the RECOS and TAU groups at baseline (T1), at integration in ShE (T2), and 6 months later (T3):

2.1. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler52];

2.2. Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale [Reference Kanter, Mulick, Busch, Berlin and Martell53];

2.3. Self-Appraisal of Illness Questionnaire;

2.4. Self-Esteem Rating Scale [Reference Lecomte, Corbière and Laisné54];

2.5. Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale [Reference Tennant, Hiller, Fishwick, Platt, Joseph and Weich55];

2.6. French Social Autonomy Scale (EAS) [Reference Leguay, Cochet, Matignon, Hairy, Fortassin and Marion56];

2.7. Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire [Reference Combs, Penn, Wicher and Waldheter57];

2.8. MIC-CR Cognitive Insight Scale [Reference Medalia and Thysen58];

2.9. Assessment of technical and interpersonal skills at work (EATR); (Annex 1).

In the RECOS group, patients benefited from specific CR by one training module (chosen with respect to the most impaired cognitive function, as measured in the neuropsychological assessment) among the five proposed by the program (reasoning, verbal memory, visual–spatial memory and attention, working memory, and selective attention). RECOS is a CR program designed for patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder [Reference Franck, Duboc, Sundby, Amado, Wykes and Demily59,Reference Deppen, Sarrasin Bruchez, Dukes, Pellanda and Vianin60]. It is acknowledged that cognitive deficits differ from one patient to another. Consequently, RECOS aims at providing individualized CR therapy. The training consists of the realization of paper-and-pencil exercises (allowing the development of adapted strategies) and computerized exercises of increasing difficulty. The therapeutic part of the program takes place at two sessions of 1 hour per week plus 1 hour of homework for 15 weeks (30 1-hour remediation sessions). Patients in the TAU group benefited from of the usual nonspecific preparation period prior to ShE inclusion for 3 months. Initial assessment and follow-up were identical in the RECOS and TAU groups.

Statistical analyses were conducted on the R Software (https://www.r-project.org) by Francq C. and colleagues. All the data from patients in their group of randomization were considered in these analyses, whatever the treatment they actually received (crossover) and whatever their future in the trial (withdrawal). We conducted an Intent-To-Treat analysis. Generalized estimation equations and multilevel analyses were conducted. This allowed to consider the impact of determined care sequences on the evolution of the quantitative parameters collected iteratively and, conversely, the way in which certain characteristics of people (cognitive and psychosocial) predict the nature of the evolution of their professional insertion.

Results

Seventy-nine patients were included in the study between October 2018 and September 2019. Twenty-six participants withdrew of the study or were lost of sight before the collection of the main outcome in ShE. Fifty-three patients completed the study (30 RECOS + 23 TAU). Among them, 30 have a complete dataset.

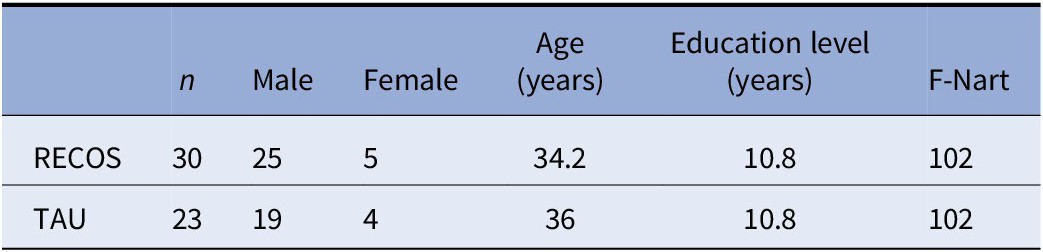

The average age was 34.2 for RECOS and 36 for TAU, and there were 5 women and 25 men in the RECOS group and 4 women and 19 men in the TAU group. There were no significant difference between the two groups at baseline on other outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants included with primary outcome evaluated (n = 53).

Abbreviation: TAU, Treatment As Usual.

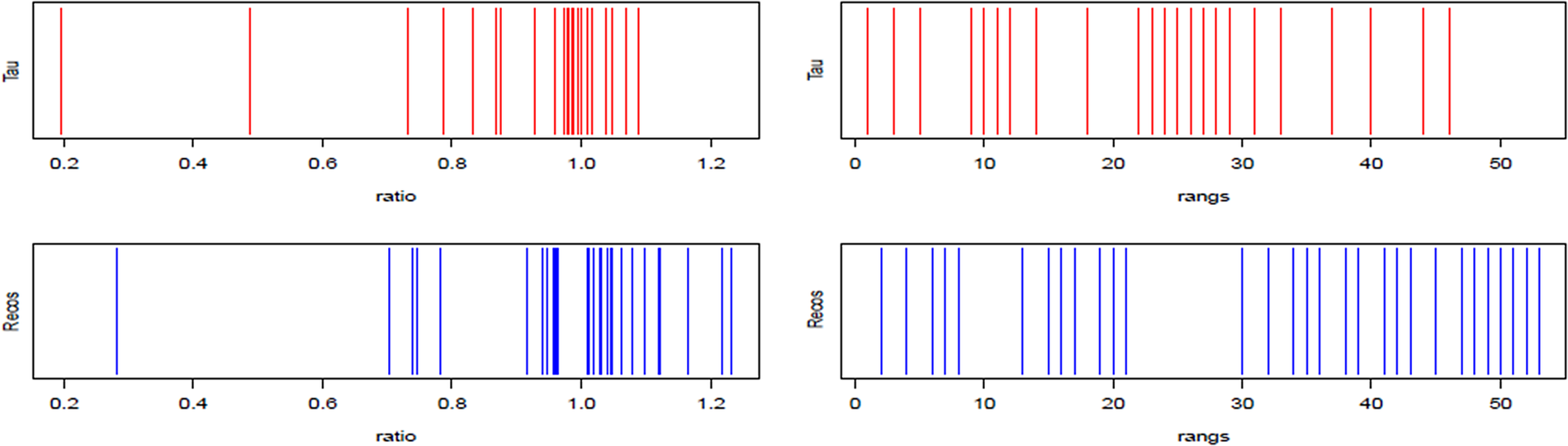

Main outcome was collected for 53 of them. The values of R ≥ 1 were obtained from workers who held their contract (=) or worked overtime (>). R < 1 values were obtained from workers who showed unjustified absenteeism or who abandoned their job before the end of the 6-month follow-up. Better performances on the main outcome were observed for the RECOS group: values of the R ratio (hours worked / planned hours) equal to 1 or greater than 1 were significantly higher in the RECOS group than in the TAU group (Figure 1 and Table 2). The distribution of the ranks of these ratios confirms this observation in favor of the RECOS group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of the variable R (left) and its ranks (right) for the Treatment As Usual and RECOS groups.

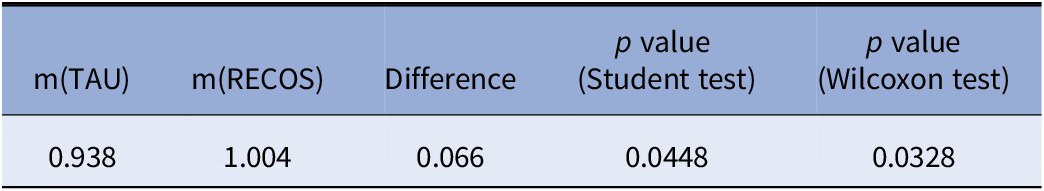

Table 2. Difference in R average values (without outliers; n = 53).

Abbreviation: TAU, Treatment As Usual.

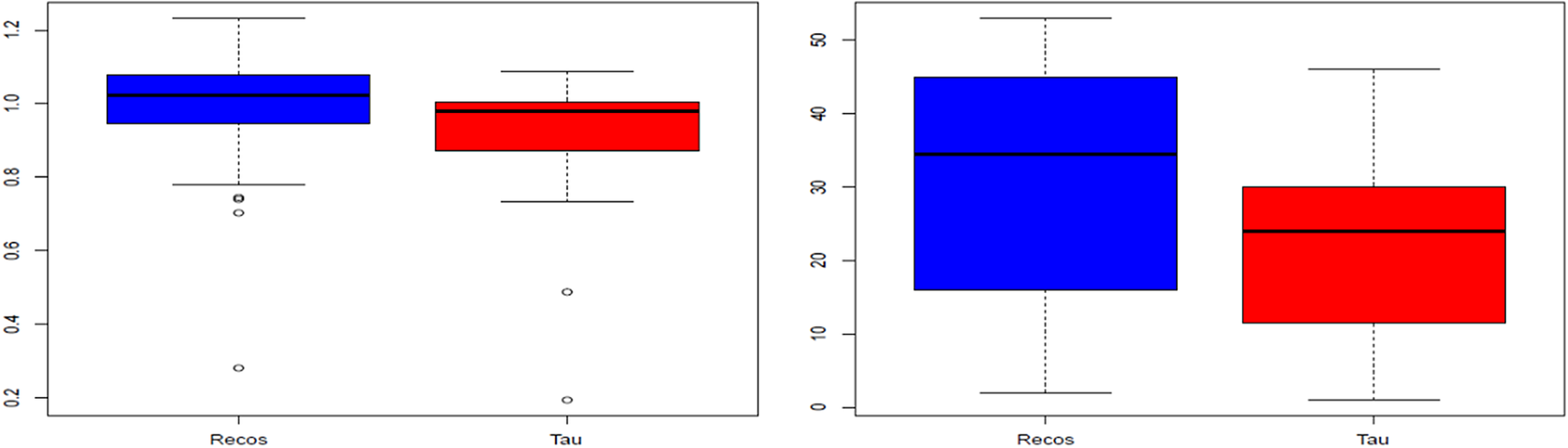

Boxplots of the distribution of R values (Figure 2) show a clear advantage for workers in the RECOS group, and this for the three quartiles [bottom of the box = first quartile or Q1; median = second quartile or Q2; top of the box = third quartile or Q3), or 75% of the total population. Extreme values (below the limit of the lower mustache) are more numerous in this arm (4 for RECOS against 2 for TAU). Among them, 2 (1 RECOS and 1 TAU) can be considered as “nonstandard.” The same observation (superiority of RECOS over TAU) can be made for the row values (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Boxplots of the variable R (left) and its ranks (right) for the Treatment As Usual and RECOS groups.

The difference in the ratios observed between the two groups is statistically significant with a risk of 10% for the total population analyzed (n = 53; Student and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests); it is also clearly significant at the risk of 5% if we eliminate the extreme values (1 in each group) corresponding to two patients with a poorly defined professional project (withdrawal from ShE after 2 or 3 months, with absenteeism therefore during these few weeks of follow-up; Table 2).

An analysis of variance was carried out to test the hypothesis that variables other than the main outcome had the same profile in the two groups at baseline (T1). For some of these variables and some individuals, we observed a lot of missing data. We therefore replaced these missing data with an empirical average calculated from the data available for other individuals. No significant difference was detected between the two groups at 5% risk, except for two variables (out of 57): the EAS (p = 0.04164) and the indirect span of the memory of figures (p = 0.01566). The population was therefore very homogeneous in the two groups at baseline (T1).

We then wanted to know if these variables had been influenced by the treatment provided. No difference in evolution between the two groups was observed for the majority of the variables considered, except for:

1. RBMT variables (verbal memory), PNEG (PANNS negative symptoms) and PPOS (PANNS positive symptoms), and EAS for which the scores are lower in the RECOS group compared to the TAU group, either between T1 and T2, T1 and T3, or both;

2. TMTA where the difference is significantly larger for RECOS than for TAU between T1 and T2.

We can also notice many “nonstandard” values for the variables FR (false recognition), RC (right recognition), and Ind (RC-FR) of the BVMT visual memory scale, which makes any analysis irrelevant.

Conclusions

The objective of this study was to assess the impact of an individualized CR program on maintaining ShE for people with schizophrenia. The main outcome was work attendance, on the assumption that the presence of cognitive deficits would affect the motivation and efficiency of people in their workplace and therefore lead to more absenteeism. We have shown that participants benefited from a RECOS individualized CR program allows a better rate of work attendance (R ratio) in ShE, compared to the ones benefited from TAU. The population studied had just entered employment, as the 3-month intervention was delivered during the preparation period (around 4 months) before taking their position. Therefore, we tested the impact of an individualized CR program which was previously validated in this population [Reference Franck, Duboc, Sundby, Amado, Wykes and Demily59,Reference Deppen, Sarrasin Bruchez, Dukes, Pellanda and Vianin60] on professional insertion in the traditional or “train and place” vocational rehabilitation model still widely use in France [Reference Pachoud, Llorca, Azorin, Dubertret, de Pierrefeu and Gaillard17–Reference Reker, Eikelmann and Inhester19].

The limitations of the study were the small number of participants compared to the number of subjects required calculated beforehand. In addition, 26 participants chose to withdraw of the study or were lost to follow-up before the first outcome was collected. In the end, the data of only 53 participants could be analyzed for the first outcome (30 RECOS + 23 TAU), and only 30 datasets were complete for the first and secondary outcomes. It was therefore difficult to conclude on secondary outcomes, and most results were not significant. The collection of secondary outcomes at baseline, however, allowed us to observe that the population was homogeneous on the different criteria between the two groups TAU and RECOS.

We can conclude from this study that traditional vocational rehabilitation or “train and place” paradigm enhanced with individualized CR in a population of patients with schizophrenia is efficient on work attendance during the first months of work integration. These observations are consistent with those observed in the literature. It is usually observed in the literature that people with a severe handicap get more opportunities in ShE than in competitive workplaces. People with schizophrenia working in competitive settings have lower symptoms, are less hospitalized, and have higher executive functions and higher functional capacity than people working in ShE or who are unemployed [Reference Lystad, Falkum, Haaland, Bull, Evensen and Bell24,Reference Lipskaya-Velikovsky, Kotler and Jarus61,Reference Eikelmann and Reker62]. They are also more likely to find employment if they were already working before hospitalization. ShE has long been the only alternative for people with schizophrenia [Reference Reker, Eikelmann and Inhester19]. The effectiveness of SE in this population has now been demonstrated; however, ShE can still remain a useful alternative for people with schizophrenia and significant cognitive difficulties, for whom it is more difficult to access competitive work market. This hypothesis is to be moderated, because it has also been observed that at an equal level of symptoms, quality of life, and self-esteem, people who enter competitive employment have better improvement on these outcomes than people who enter ShE [Reference Bond, Resnick, Drake, Xie, McHugo and Bebout12]. Above all, access to competitive employment for these people should be encouraged by making it more inclusive and allowing the necessary adaptations to persistent cognitive difficulties.

Further studies would be required to study the maintenance of the beneficial effects observed over time, both on cognitive parameters and on work attendance and other functional outcomes in ShE. Furthermore, RemedRehab studied the impact of the remediation of neurocognitive disorders in access and job maintaining in traditional vocational rehabilitation, but it would be interesting to study the impact of social cognition training on these same parameters.

Financial Support

This work was funded by PHRC (French Government Funding Program for Clinical Research).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare related to this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.