1. Introduction

Gender differences in schizophrenia have attracted the attention of scientific research for more than a century. Kraepelin had already reported that women are older at first admission for dementia praecox compared to men [Reference Kraepelin1]. Most studies to date confirm these findings [Reference Riecher-Rössler, Butler and Kulkarni2]. Findings on severity of psychopathological symptoms are less conclusive, with some authors suggesting that men have more severe negative symptoms while women show more severe affective and specific psychotic symptoms [Reference Riecher-Rössler, Butler and Kulkarni2]. However, only few gender differences in psychopathology of first episode schizophrenia were found in the ABC study, and these were not significant after correction for multiple testing [Reference Häfner, Riecher-Rössler, Fätkenheuer, Hambrecht, Löffler and An der Heiden3, Reference Häfner, Maurer, Löffler and Riecher-Rössler4]. With regard to substance abuse, available evidence suggests that men have a higher prevalence of substance abuse and higher levels of comorbidity compared to women. Additionally, studies examining gender differences in premorbid and social functioning have found higher functioning in women [Reference Riecher-Rössler, Butler and Kulkarni2].

In the past two decades, the field of early detection of psychosis has received growing scientific and clinical interest [Reference Riecher-Rössler and McGorry5], albeit that only few methodologically sound studies have considered gender differences in patients with an at-risk mental state (ARMS) for psychosis. These studies have thus far yielded inconsistent results. With regard to symptomatology, most studies described in the comprehensive review of Barajas et al. [Reference Barajas, Ochoa, Obiols and Lalucat-Jo6] reported no gender differences in ARMS patients. Nevertheless, some studies found more severe negative symptoms in men, and other studies found lower levels of social functioning and a longer duration of untreated illness in men compared to women [Reference Barajas, Ochoa, Obiols and Lalucat-Jo6]. A more recent review published by Riecher-Rössler et al. [Reference Riecher-Rössler, Butler and Kulkarni2] suggests that gender differences in the symptomatology of patients at risk are small and comparable to those seen in the general population. Thus, in a representative worldwide general population sample of 72,933 subjects, men in general had a greater propensity to substance, alcohol and cannabis abuse, while women had more affective symptoms, depression and anxiety [Reference Seedat, Scott, Angermeyer, Berglund, Bromet and Brugha7].

In addition to the at-risk signs and symptoms for psychosis, many ARMS patients suffer from comorbid non-psychotic mental disorders, in particular depression and anxiety disorders [Reference Albert, Tomassi, Maina and Tosato8, Reference Fusar-Poli, Nelson, Valmaggia, Yung and McGuire9]. To our knowledge, only two studies have investigated gender differences in comorbid depressive and anxiety diagnoses in ARMS patients at baseline. Kline et al. [Reference Kline, Seidman, Cornblatt, Woodberry, Bryant and Bearden10] examined a cohort of 764 ARMS patients (women, n = 329; 43%) from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS-2), and observed a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of depression in women than men (64% vs. 56%). No significant gender differences in comorbid affective and anxiety disorders were observed in the study of Rietschel et al. [Reference Rietschel, Lambert, Karow, Zink, Müller and Heinz11].

To further elucidate these issues, the present study investigated gender differences in symptomatology, drug use, comorbidity (i.e. substance use, affective and anxiety disorders) and global functioning in a large multinational sample of ARMS patients. Based on previous and our own findings, we expected to find no significant differences between ARMS men and women.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and recruitment

The data analysed in this study were collected within the multicenter EUropean Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) study, from May 1, 2010 to April 30, 2015. The aim of EU-GEI study is to identify the interactive genetic, clinical and environmental determinants of schizophrenia [Reference Kraan, Velthorst, Themmen, Valmaggia, Kempton and McGuire12]. The overall design of the study was naturalistic, longitudinal and prospective, consisting of a baseline and two follow-up time points. For the current analyses, only baseline, i.e. at intake into the study, data were used and only patients with complete data on cannabis frequency were included.

ARMS patients were recruited from 11 Early Detection and Intervention Centers, nine in Europe (London, Amsterdam, The Hague, Vienna, Basel, Cologne, Copenhagen, Paris, Barcelona), one in Brazil (Saõ Paulo), and one in Australia (Melbourne). Referrals were accepted from primary health care services, mental health professionals, or from the subject or their family. Study intake corresponds to the admission date in the early detection service. All participants were screened with an inclusion/exclusion checklist (see below).

The protocol of the EU-GEI study was approved by the institutional review boards of all study sites. EU-GEI was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Medical Ethics Committees of all participating sites approved the study protocol.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for EU-GEI were: aged 18–35; being at-risk for psychosis as defined by the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State (CAARMS) [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Philips, Kelly and Dell'olio13]; adequate language skills local to each center; and consent to study participation.

The exclusion criteria were: prior experience of a psychotic episode of more than 1-week as determined by the CAARMS [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Philips, Kelly and Dell'olio13] and Structural Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) [Reference Wittchen, Zauding and Fydrich14]; previous treatment with an antipsychotic for a psychotic episode; and IQ < 60.

2.3. Determination of ARMS status

The CAARMS, used to identify ARMS patients [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Philips, Kelly and Dell'olio13], is a semi-structured interview that encompasses psychotic symptoms and a range of other psychopathological symptoms occurring in emerging psychotic disorder. Individuals were classified as being in an ARMS for psychosis if they met at least one of the following risk criteria: (i) Vulnerability Group (a first-degree relative with a psychotic disorder or diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder in combination with a significant drop in functioning); (ii) Attenuated Psychotic Symptoms (APS) (psychotic symptoms sub-threshold either in intensity or frequency); (iii) Brief Limited Psychotic Symptoms (BLIPS) (recent episode of brief psychotic symptoms that spontaneously resolved within 1 week). The full criteria can be found in Yung et al. [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Philips, Kelly and Dell'olio13].

2.4. Assessment of sociodemographic characteristics and medication

Sociodemographic characteristics were obtained using the modified Medical Research Council (MRC) sociodemographic schedule [Reference Mallett15]. Data on psychiatric medication were assessed with a medical history questionnaire, designed by the EU-GEI group.

2.5. Assessment of psychopathology

Psychopathological symptoms were assessed using the expanded version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-E) [Reference Shafer, Dazzi and Ventura16], the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) [Reference Andreasen17], the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Metal State (CAARMS) [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Philips, Kelly and Dell'olio13], the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [Reference Montgomery and Asberg18], and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) [Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer19]. Genders differences were investigated using the following subscales:

BPRS-E: Activation, Positive symptoms, Negative symptoms, Affect, Disorganization as defined by Shafer et al. [Reference Shafer, Dazzi and Ventura16] and the total score

SANS: Affective Flattening, Alogia, Asociality-Anhedonia, Avolition-Apathy, Inattention and the total score [Reference Andreasen17]

CAARMS: Behavioral change, Cognitive change - attention/concentration, Emotional disturbance, Motor/physical changes, Negative symptoms, Positive symptoms, General Psychopathology [Reference Miyakoshi, Matsumoto, Ito, Ohmuro and Matsuoka20]

MADRS: Detachment, Negative Thoughts, Neurovegetative, Sadness as defined by Quilty et al. [Reference Quilty, Robinson, Rolland, De Fruyt, Rouillon and Bagby21] and the total score

YMRS: Total score [Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer19]

2.6. Assessment of comorbidity, drug use and functioning

Affective and anxiety disorders were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic Manual of Psychiatric Disorders-IV (DSM-IV/SCID) [Reference Wittchen, Zauding and Fydrich14]. Current use, abuse and dependence of cannabis, amphetamine (e.g. speed, ecstasy), cocaine, and hallucinogens (e.g. lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), “magic mushrooms”) were assessed using the Cannabis Experience Questionnaire [Reference Barkus, Stirling, Hopkins and Lewis22]. For cannabis, the frequency of use was additionally assessed. Participants were defined as being current users of a substance if they identified themselves as such or if they reported any use in the preceding month.

The general level of functioning was assessed with the GAF scale [Reference Goldman, Skodol and Lave23].

2.7. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out using R environment for statistical computing [Reference Team24]. Because observations were non-independent, that is, observations from the same center were more similar than observations from different centers, gender differences were analysed using mixed effects models including gender as a fixed effects factor and randomly varying intercepts per center to account for the clustering in the data. We used linear mixed effects models for continuous measures (i.e. age, years of education, functioning and psychopathology scales), mixed effects logistic regression models for binary measures (i.e. psychiatric diagnoses, drug use and psychiatric medication), ordinal mixed effects models for ordered categorical measures (i.e. cannabis frequency and highest level of education) and mixed effects multinomial logistic regression for unordered categorical measures (i.e. living situation). We analysed gender differences in the frequency of use of antipsychotics, antidepressants and hypnotics. Cannabis frequency and age were included as covariates in models estimating gender differences in psychopathology and living situation, respectively. Continuous dependent variables were z-transformed before inclusion to models and gender was included as a binary variable with 0 and 1 describing men and women, respectively. Thus, the regression coefficient for gender described the standardized mean difference of women compared to men. P-values were adjusted for multiple testing across all of the 63 gender differences tests using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) procedure [Reference Benjamini and Hochberg25].

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

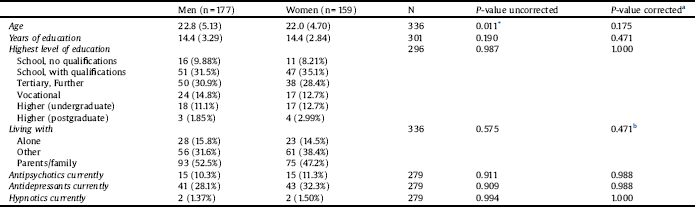

In total, 345 ARMS patients participated in the EU-GEI study. The sample of this study consisted of 336 ARMS patients (177 men, 159 women). 9 ARMS patients had not complete data on cannabis frequency and were excluded. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Male patients were significantly older than female patients in unadjusted analyses (P = 0.011). The significance of this effect disappeared after correction for multiple testing (P = 0.175). There were no significant gender differences in ARMS patients with regard to years of education, highest level of education, living situation and current psychiatric medication.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Continuous variables are described by means and standard deviations in parentheses.

a P-value corrected for multiple testing.

b P-value corrected for age and multiple testing.

3.2. Gender differences in symptomatology and functioning

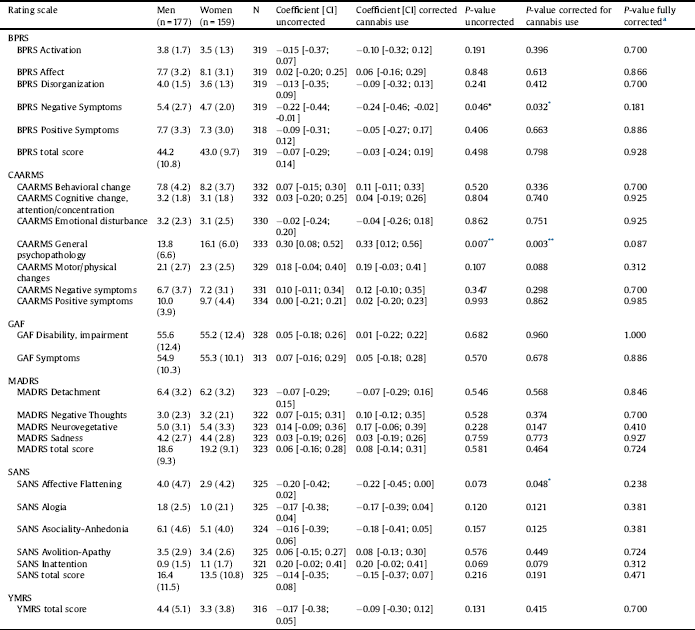

Table 2 shows the results of the linear mixed effects models using symptomatology as continuous dependent variable and gender as fixed effects factor. Standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals of the psychopathological syndrome scales are additionally presented in Fig. 1.

Female ARMS patients showed significantly less severe BPRS “Negative Symptoms” (b = −0.22, P = 0.046), more CAARMS “General psychopathology” (b = 0.30, P = 0.007) and trendwise less SANS “Affective Flattening” (b = −0.20, P = 0.073) than male ARMS patients in uncorrected analyses. These differences became significant when corrected for cannabis use (BPRS: b = −0.24, P = 0.032; CAARMS: b = 0.33, P = 0.003, SANS: b = −0.22, P = 0.048). However, when p-values were additionally adjusted for multiple testing by using the FDR procedure, differences in negative symptoms and general psychopathology were no longer significant. There were no gender differences in ARMS patients with regard to global functioning.

3.3. Gender differences in drug use and comorbidity

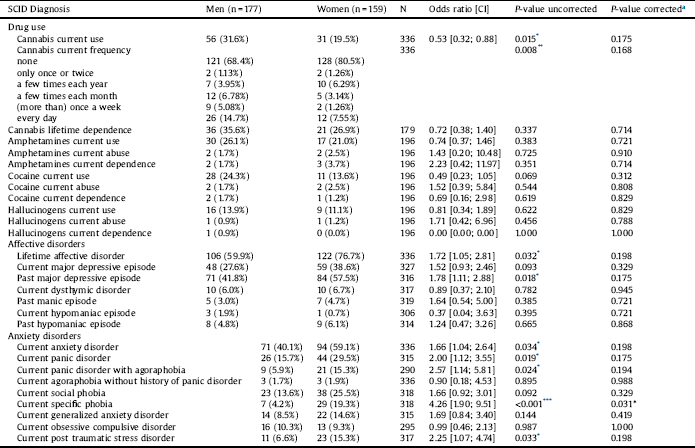

Table 3 shows the ORs for associations of gender with comorbid drug use and affective and anxiety disorders for ARMS patients at baseline. Unadjusted ORs indicate that men had a significantly higher proportion of current cannabis users (OR, 0.53; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.88; P = 0.015) and a higher current frequency of cannabis use than women (P = 0.008).

Table 2 Gender differences in psychopathology and functioning.

BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CAARMS: Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; MADRS: Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale;

SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale; CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

a P-value corrected for cannabis use and multiple testing.

* P < 0.05.

Fig. 1. Standardized mean differences (d) and 95% confidence intervals of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Comprehensive Assessment At-Risk Mental State (CAARMS), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). The bold vertical line at zero represents the severity of symptomatology in men. Differences are significant if the 95% confidence interval (horizontal line) does not overlap with zero.

With regard to broad diagnostic categories, women were significantly more often diagnosed with any lifetime affective disorder (OR, 1.72; 95% CI 1.05–2.81; P = 0.032) and any current anxiety disorder (OR, 1.66; 95% CI 1.04–2.64; P = 0.034). With regard to specific diagnoses, women were more frequently diagnosed with a past major depressive episode (OR, 1.78; 95% CI 1.11–2.88; P = 0.018), a current panic disorder with (OR, 2.57; 95% CI 1.14–5.81; P = 0.024) and without agoraphobia (OR, 2.00; 95% CI 1.12–3.55; P = 0.019), current specific phobia (OR, 4.26; 95% CI 1.90–9.51; P = < 0.001) and current PTSD (OR, 2.25; 95% CI 1.07–4.74; P = 0.033). However, when adjusted for multiple testing, only current specific phobia remained significantly associated with gender (P = 0.031).

4. Discussion

The current study investigated gender differences in sociodemographic variables, symptomatology, drug use, comorbidity (i.e. substance use, affective and anxiety disorders) and global functioning in 336 ARMS patients presenting for the first time at an early detection service in a multi-national study. Unadjusted analyses indicated higher severity of negative symptoms (i.e. BPRS negative symptoms, SANS affective flattening) and current cannabis use in men while women showed higher severity of general psychopathology (CAARMS) and suffered more from comorbid affective (i.e. lifetime affective disorders, past major depressive episode) and anxiety disorders (e.g. panic, panic with agoraphobia, specific phobia, PTSD). However, when corrected for multiple testing and confounding variables, these differences were no longer significant except for higher lifetime rates of specific phobia in women.

Regarding sociodemographic variables, our results are in agreement with an earlier study on ARMS patients [Reference Rietschel, Lambert, Karow, Zink, Müller and Heinz11] with the exception of age and living situation. While Rietschel et al. [Reference Rietschel, Lambert, Karow, Zink, Müller and Heinz11] found no gender difference in age, the current study found male ARMS patients to be significantly older than female ARMS patients but only if statistically not corrected for multiple testing. Rietschel et al. [Reference Rietschel, Lambert, Karow, Zink, Müller and Heinz11] suggest that male ARMS patients are living more frequently with their parents or other relatives than female ARMS patients whereas the present study did not find any significant gender differences. This finding may be due to the slightly lower average age in our sample. Another possibility is that this gender difference is dependent on the country or region the sample is taken from.

Table 3 Gender differences in drug use and comorbidity.

SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic Manual of Psychiatric Disorders DSM-IV; CI: 95% Confidence Interval.

a P-value corrected for multiple testing.

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

** P < 0.01.

* P < 0.05.

Regarding psychopathology, our findings were in line with a previous study of our own group that reported no gender differences in psychopathology, neither in ARMS nor in FEP patients, when corrected for multiple testing [Reference Gonzalez-Rodriguez, Studerus, Spitz, Bugra, Aston and Borgwardt26]. Furthermore, Willhite et al. [Reference Willhite, Niendam, Bearden, Zinberg, O’Brien and Cannon27] also found no significant gender differences in ratings of any of the symptoms of the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS) in high-risk patients. A possible explanation may be that gender differences in the symptoms are so small that they can only be reliably detected in studies with very high statistical power (i.e. in very large datasets or in meta-analyses). However, such small effects would likely not be clinically meaningful.

Regarding drug use and comorbidity, male ARMS patients showed higher rates of current cannabis use and frequency of intake in unadjusted but not in adjusted analyses compared to female ARMS patients. This finding is in line with a previous study of our own group [Reference Gonzalez-Rodriguez, Studerus, Spitz, Bugra, Aston and Borgwardt26] and others that report no gender differences regarding substance abuse in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia [Reference Riecher-Rössler, Butler and Kulkarni2]. However, higher rates of substance abuse in men are found in the general population [Reference Seedat, Scott, Angermeyer, Berglund, Bromet and Brugha7] and in schizophrenia in particular [Reference Riecher-Rössler, Butler and Kulkarni2].

Our finding of higher rates of comorbid affective and anxiety disorders in female ARMS patients contradicts a recent study on ARMS patients, which has found no gender differences for affective and anxiety disorders [Reference Rietschel, Lambert, Karow, Zink, Müller and Heinz11]. However, an earlier study found greater rates of current depression and social anxiety in high-risk women compared to men [Reference Rietdijk, Ising, Dragt, Klaassen, Nieman and Wunderink28]. Furthermore, Pruessner et al. [Reference Pruessner, Faridi, Shah, Rabinovitch, Iyer and Abadi29] also found more depressive symptoms in high-risk women, but these differences did not withstand correction for multiple testing. An explanation may be that the self-report questionnaires used in the study of Rietdijk et al. [Reference Rietdijk, Ising, Dragt, Klaassen, Nieman and Wunderink28] have led to an overestimation of the number of patients with an anxiety disorder or depression. Most importantly, our results are in line with epidemiological studies on depression and anxiety in the general population, which found female/male prevalence ratios of 2:1, respectively [Reference McLean, Asnaani, Litz and Hofmann30, Reference Riecher-Rössler, Pflueger, Borgwardt and Kohen31]. ARMS patients in this respect thus do not seem to differ from the general population.

Our finding of no gender difference in terms of level of functioning is in accordance with previous studies [Reference Riecher-Rössler, Butler and Kulkarni2].

A strength of our study is that we examined gender differences with several, well established instruments to assess a broad range of symptomatology. Rater trainings have been used to ensure that all raters administering the rating scales in the same way. Furthermore, the multicentre design of our study might have contributed to heterogeneity in our sample through, for example, different cultural modes of expression and accessibility and potency of cannabis products in different study centres. We have therefore included random intercepts that varied across study centres in all our models. Finally, this is one of the first studies to investigate gender differences in symptomatology in an ARMS sample of this size.

However, although data were collected by well-trained interviewers using standardized questionnaires and well-established diagnostic criteria, this does not completely eliminate possible gender-specific biases, e.g. of questionnaires and interviewing techniques, of self-reporting, or interpreting patient information, of applying diagnostic criteria or attributing diagnostic labels [Reference Riecher-Rössler32]. Furthermore, this study concentrates on the age group of 18–35 years with the consequence that especially boys, who are at-risk state presumably before age 18 and women with later age of onset are missed. An additional limitation could be that our sample may not be representative for the overall population of help-seeking patients since we do not know whether all ARMS patients in the relevant catchment areas were searching help and came to an early detection service. A recent study found a significantly different gender distribution between ARMS and first episode psychosis (FEP) patients with a greater proportion of males in FEP cohorts than in clinical high-risk cohorts [Reference Wilson, Patel and Bhattacharyya33]. The authors presume that ARMS men are probably less likely to be help-seeking or less ‘literate’ of symptoms of mental illness which could lead to an under-representation of men in existing clinical high-risk services. Lastly, it should be noted that ARMS patients represent a heterogeneous patient group with only about 20–35% developing frank psychosis [Reference Fusar-Poli, Borgwardt, Bechdolf, Addington, Riecher-Rössler and Schultze-Lutter34, Reference Riecher-Rössler and Studerus35] and about one third having a clinical remission within the first two years of the follow-up [Reference Beck, Andreou, Studerus, Heitz, Ittig and Leanza36]. Hence, gender differences reported in this study cannot be generalized to patients being in true prodromal state for psychosis.

Taken together, our findings indicate that gender differences in symptomatology – if present at all – are so small that they are likely not to be clinically meaningful.

Disclosure of interest

All authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest that might be interpreted as influencing the content of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union (European Community’s Seventh Framework Program [grant number HEALTH-F2-2010-241909; Project EU-GEI]). M.J.K. was supported by a Medical Research Council Fellowship [grant number MR/J008915/1].

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients who participated in the study as well as the referring specialists.

Apppendix A

EU-GEI High Risk Study Group – Author List

Philip McGuire2, Lucia R. Valmaggia3, Matthew J. Kempton2, Maria Calem2, Stefania Tognin2, Gemma Modinos2, Lieuwe de Haan4,7, Mark van der Gaag8,10, Eva Velthorst5,11, Tamar C. Kraan6, Daniella S. van Dam4, Nadine Burger7, Barnaby Nelson12,13, Patrick McGorry12,13, G Paul Amminger12,13, Christos Pantelis14, Athena Politis12,13, Joanne Goodall12,13, Anita Riecher-Rössler1, Stefan Borgwardt1, Charlotte Rapp1, Sarah Ittig1, Erich Studerus1, Renata Smieskova1, Rodrigo Bressan15, Ary Gadelha15, Elisa Brietzke16, Graccielle Asevedo15, Elson Asevedo15, Andre Zugman15, Neus Barrantes-Vidal17, Tecelli Domínguez-Martínez18, Anna Racioppi19, Paula Cristóbal-Narváez19, Thomas R. Kwapil20, Manel Monsonet19, Mathilde Kazes21, Claire Daban21, Julie Bourgin21, Olivier Gay21, Célia Mam-Lam-Fook21, Marie-Odile Krebs21, Dorte Nordholm22, Lasse Randers22, Kristine Krakauer22, Louise Glenthøj22, Birte Glenthøj23, Merete Nordentoft22, Stephan Ruhrmann24, Dominika Gebhard24, Julia Arnhold25, Joachim Klosterkötter24, Gabriele Sachs26, Iris Lasser26, Bernadette Winklbaur26, Philippe A. Delespaul27,28, Bart P. Rutten29, and Jim van Os29,30

Affiliations

1 University Psychiatric Hospital, Wilhelm Klein-Strasse 27, CH-4002 Basel, Switzerland; 2 Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark 458 Hill, London, United Kingdom SE5 8AF; 3 Department of Psychology, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, 456 London, United Kingdom SE5 8AF; 4 Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Psychiatry, Department Early Psychosis, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 5 Department of Psychiatry and Seaver Center for Research and Treatment, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NY, US; 6 Mental Health Institute Arkin, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 7 Arkin Amsterdam; 8 VU University, Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Sciences, Department of Clinical Psychology and Amsterdam Public Mental Health research institute, van der Boechorststraat 7, 1081 BT Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 9 Mental Health Institute Noord-Holland Noord, Hoorn, the Netherlands; 10 Parnassia Psychiatric Institute, Department of Psychosis Research, Zoutkeetsingel 40, 2512 HN The Hague, The Netherlands; 11 Early Psychosis Section, Department of Psychiatry, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 12 Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, University of Melbourne; 13 Centre for Youth Mental Health, University of Melbourne, 35 Poplar Road (Locked Bag 10), Parkville, Victoria 485 3052, Australia; 14 Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre, The University of Melbourne; 15 LiNC - Lab Interdisciplinar Neurociências Clínicas, Depto Psiquiatria, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo – UNIFESP; 16 Depto Psiquiatria, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo – UNIFESP; 17 Departament de Psicologia Clínica i de la Salut (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), Fundació Sanitària Sant Pere Claver (Spain), Spanish Mental Health Research Network (CIBERSAM); 18 CONACYT-Dirección de Investigaciones Epidemiológicas y Psicosociales, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz (México); 19 Departament de Psicologia Clínica i de la Salut (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona); 20 Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (USA); 21 University Paris Descartes, Hôpital Sainte-Anne, C’JAAD, Service Hospitalo-Universitaire, Inserm U894, Institut de Psychiatrie (CNRS 3557) Paris, France; 22 Mental Health Center Copenhagen and Center for Clinical Intervention and Neuropsychiatric Schizophrenia Research, CINS, Mental Health Center Glostrup, Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Copenhagen, University of Copenhagen; 23 Centre for Neuropsychiatric Schizophrenia Research (CNSR) & Centre for Clinical Intervention and Neuropsychiatric Schizophrenia Research (CINS), Mental Health Centre Glostrup, University of Copenhagen, Glostrup, Denmark; 24 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; 25 Psyberlin, Berlin, Germany; 26 Medical University of Vienna, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy; 27 Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Maastricht University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD 464 Maastricht, The Netherlands; 28 Mondriaan Mental Health Trust, P.O. Box 4436 CX Heerlen, The Netherlands; 29 Medical University of Vienna, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy; 30 Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark 458 Hill, London, United Kingdom SE5 8AF.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.