A. Introduction

Robert Alexy is one of the most prominent proponents of proportionality in international legal scholarship. The influence of his work can barely be overstated. He has not only had a significant impact on the international academic discussion, but he has also been an important source of inspiration for many apex courts, in particular in Latin America.Footnote 1 His theory has two dimensions. On the one hand, it is a normative defense of balancing against critics who claim that balancing is irrational. On the other hand, it seeks to provide a reconstruction of the case law of the German Federal Constitutional Court. The normative part of his theory has already been controversially discussed.Footnote 2 Yet, the reconstructive part of his theory has received much less scrutiny. Still, it is often considered to be representative of the “German” approach to proportionality.Footnote 3

In this Article, I argue that Alexy’s reconstruction of the fundamental rights jurisprudence of the German Federal Constitutional Court is only partly accurate: While his theory of fundamental rights provides a good description of the German Constitutional Court’s reasoning in horizontal fundamental rights cases, it is inaccurate with regard to decisions in which the Constitutional Court declares a piece of legislation unconstitutional. For this reason, the critique of Alexy’s theory does not necessarily translate into a critique of the jurisprudence of the German Constitutional Court’s application of proportionality or even the proportionality doctrine itself. It targets only one specific interpretation of proportionality.

This Article will proceed in four steps. It will first briefly introduce Alexy’s theory of constitutional rights to the extent that it concerns the proportionality test. Second, it will give a concise account of the normative critique of Alexy. The third and the fourth sections are then concerned with the reconstructive dimension of Alexy’s theory. I will show that Alexy paints an accurate picture of the jurisprudence of the German Constitutional Court to the extent that it concerns horizontal fundamental rights cases. It fails, however, to describe the arguably more important dimension regarding constitutional review of legislation. In the final part, I offer a more modest normative defense of proportionality.

B. Alexy’s Theory of Constitutional Rights

Robert Alexy’s A Theory of Constitutional Rights is one of the most important monographs that has been written on German constitutional rights.Footnote 4 The main purpose of the book is a description and conceptualization of the fundamental rights doctrine of the German Federal Constitutional Court. Alexy draws on Ronald Dworkin’s distinction between rights and principlesFootnote 5 and argues that fundamental rights are primarily principles.Footnote 6 But he also modifies Dworkin’s theoretical distinction by positing that principles are optimization requirements according to which a conflict between two principles must be resolved in a way that jointly maximizes their reach.Footnote 7

According to Alexy, the proportionality test is a “logical” consequence of the conceptualization of constitutional rights as principles.Footnote 8 He considers the balancing step to be the core of the proportionality test and establishes the “Law of Balancing,” according to which “the permissible level of non-satisfaction of, or detriment to, one principle depends on the relative importance of satisfying the other.”Footnote 9 He defends against the critique that balancing is irrational by pointing out that judicial discretion is an integral part of judicial decision-making and not unique to balancing.Footnote 10

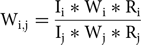

In later contributions, Alexy extends his description and normative defense of balancing.Footnote 11 In particular, he develops the weight formula, which compares several factors of the concerned constitutional rights and the public aim justifying the restriction.Footnote 12 He separately calculates the product of weight (W), the intensity of restriction (I), and the resilience of the empirical assumptions (R) of the two competing aims and then divides the one by the other:Footnote 13

$${\rm{W_{i,j}} = \frac{{{{I_i}*{\rm{ }}{W_i}*{\rm{ }}{R_i}}}\over{{{I_j}*{\rm{ }}{W_j}*{\rm{ }}{R_j}}}$$

$${\rm{W_{i,j}} = \frac{{{{I_i}*{\rm{ }}{W_i}*{\rm{ }}{R_i}}}\over{{{I_j}*{\rm{ }}{W_j}*{\rm{ }}{R_j}}}$$If Wi,j is greater than one, principle i is more important than principle j; if it is smaller than one, j is more important than i.Footnote 14 Through his book and his articles, Alexy’s argument is not exclusively normative. Instead, he often refers to specific judgments of the German Federal Constitutional Court to demonstrate his point. Implicitly, he claims that his theory of constitutional rights provides not only a normative defense of balancing, but also an adequate description of the jurisprudence of the German Constitutional Court on constitutional rights.

C. The Normative Critique of Alexy

Alexy’s theory has not remained unchallenged.Footnote 15 In particular, critics claim that the structure of balancing as it is proposed by Alexy in his Law of Balancing leads to irrational decision-making because it forces judges to compare incommensurable values.Footnote 16 In particular, in response to Habermas’ critique, Alexy developed his weight formula. In this formula, he uses ordinal values that allow a ranking between different options. For example, he distinguishes between light, moderate, and serious restrictions of fundamental rights.Footnote 17 Yet, ordinal values only allow for a ranking; they do not contain information about the distance between two values.Footnote 18 We can say that moderate restrictions are more severe than light restrictions, but we cannot say that moderate restrictions are twice or thrice as severe as light restrictions.

This is, however, exactly what Alexy does when he operationalizes his weight formula by assigning values to the different options and then using these for multiplications and divisions. Such mathematical operations are prohibited for ordinal values because we cannot say anything about their relation. Alexy assigns the value 1 to light restrictions, 2 to moderate restrictions, and 4 to serious restrictions.Footnote 19 But, the choice of these values is completely arbitrary.Footnote 20 One could have chosen 1, 10, and 15 instead, which would lead to different outcomes of the mathematical operations. There is not a single argument that Alexy can make to justify why his numerical operationalization of the weight formula is superior to any alternative operationalization.Footnote 21

This critique of the weight formula does not undermine balancing as such. It shows only that the operation with mathematical formulas creates a false illusion of rationality and determination. Yet, the simple fact that balancing requires a comparison of incommensurable values does not automatically lead to the conclusion that it is irrational. Instead, human beings have to make choices between incommensurable values all the time.Footnote 22 Even in legal reasoning, balancing in the context of constitutional rights is not all that exceptional.Footnote 23 We also find it in other legal fields, such as labor law, tort law, and criminal law, where it is much less controversial.Footnote 24

What, then, is special about balancing in constitutional law? If we want to regulate abortions, we must make a choice between the right to life of the embryo and the right of the mother to control her own body, even if these two values are incommensurable. Even critics of balancing acknowledge that such a choice must be made. Nonetheless, they argue that such a choice must be made by the legislature rather than judges who are not accountable to the electorate.Footnote 25 The argument about the rationality of balancing thus turns into an institutional argument about the relationship between courts and the legislature, and ultimately about the function of constitutional courts in a democracy.Footnote 26

This Article is not the right place to enter into the discussion on the proper role of constitutional courts.Footnote 27 But if the question regarding the normative acceptability of balancing in constitutional rights jurisprudence hinges on the relationship between courts and the legislature, we must differentiate between three situations in which balancing is employed. First, balancing is often used in horizontal rights cases where the court must resolve a conflict between constitutional rights of individuals. These cases do not concern the relationship between courts and the legislature. Instead, apex courts control and correct decisions that lower courts have made so that the relationship between the legislature and the judiciary is not affected. Second, balancing comes into play when an apex court confirms the constitutional validity of a piece of legislation. Again, there is no conflict between the court and the legislature because the court supports the decision of the latter.

The problematic constellation is the third situation where a constitutional court declares a law to be incompatible with the constitution. Here, we need a specific justification for why the court’s evaluation of the value conflict between the constitutional right and the public purpose pursued by the legislature trumps the legislature’s evaluation of the same value conflict. Instead of producing a normative justification for this last constellation, the remainder of this Article analyzes the case law of the German Federal Constitutional Court. I argue that Alexy’s model of constitutional rights provides an accurate description of the Court’s practice in the first two constellations. Yet, we see a noticeable difference when it comes to the third constellation in which the Court challenges the legislature. Here, the reasoning does not follow Alexy’s model, but relies on much more limited grounds.

D. Horizontal Constitutional Rights Cases and Confirmation of the Legislature

The German Constitutional Court already extended the effect of constitutional rights to horizontal rights cases in its early jurisprudence. In its famous Lüth judgment,Footnote 28 the Court argued that private law courts had to take constitutional rights into account when resolving disputes between individuals.Footnote 29 In the case at hand, Erich Lüth—the director of the press office in Hamburg—called for a boycott of the latest movie of Veit Harlan, a movie director who had played a prominent role during the time of the Nazi government. The movie producer brought a case to the High Court of Hamburg and obtained an injunction against Lüth. Lüth challenged the High Court decision before the German Constitutional Court and argued that it violated his freedom of expression.

The Constitutional Court took up the case and argued that constitutional rights were not only valid in the relationship between the State and individual, but that they also had to be taken into account by private law courts. They relied on balancing in order to resolve the conflict between Lüth’s freedom of expression and Harlan’s professional reputation.Footnote 30 The structure of the balancing test resembles Alexy’s Law of Balancing.Footnote 31 The Court analyzed the abstract weight of the competing values and the extent to which they are concerned.Footnote 32

Lüth is not the only example of a horizontal rights case where the Court relies on a balancing test whose structure follows Alexy’s Law of Balancing.Footnote 33 Alexy himself cites two further examples. In his monograph, he resorts extensively to the Lebach case to demonstrate the reconstructive part of this theory.Footnote 34 In Lebach, the Court had to deal with a conflict between the right to privacy of a convict and the freedom of the press of a public broadcaster who wanted to air a documentary about the crime that had been committed by the applicant.Footnote 35 The Court found that the broadcasting of the documentary was disproportionate: On the one hand, it included information that allowed an identification of the applicant and, on the other hand, the timing of the broadcast fell together with the applicant’s release from prison and thus made his resocialization more difficult. In his later contributions, Alexy also referred to the Titanic case, in which a satirical magazine called an individual a “born murderer” and classified him as one of the seven most embarrassing personalities.Footnote 36 Again, the Court relied on balancing to resolve the conflict between the magazine’s freedom of the press and the right to privacy of the concerned individual.Footnote 37

Stephen Gardbaum has recently pointed out that the structure of horizontal conflicts of rights differs fundamentally from negative rights cases, which deal with the restriction of constitutional rights through government action.Footnote 38 This is also reflected in the structure of the proportionality test. Gardbaum observes that courts dealing with horizontal rights cases usually resort only to balancing while the other steps of proportionality are reserved to negative rights cases.Footnote 39 Therefore, if Alexy’s Law of Balancing adequately reconstructs the German Constitutional Court’s case law in horizontal rights cases, this does not automatically mean that his reconstruction is representative of the whole German constitutional jurisprudence.

Alexy’s examples, however, do not refer only to horizontal rights cases. He also cites cases in which the Court reviewed pieces of legislation. In particular, he refers to the Tobacco Warning and the Cannabis decisions of the German Constitutional Court.Footnote 40 In the Tobacco Warning decision, the Court had to deal with the compatibility of executive orders that require health warnings on packages for tobacco products with the freedom of profession of tobacco producers.Footnote 41 The Court acknowledged that the health warning requirement restricted the freedom of profession, but it also found that it was proportionate and therefore justified. It argued that there was no less restrictive and equally effective means to protect human health, and that this goal also outweighed the tobacco producer’s commercial interests.Footnote 42 In the Cannabis decision, the Court dealt with the constitutionality of the criminalization of cannabis consumption.Footnote 43 It put the main emphasis of its argument on the balancing test and argued that the protection of human health justified the prohibition of cannabis consumption.

That the structure of the Court’s reasoning in cases where the judges confirm a piece of legislation reflects Alexy’s Law of Balancing is not very surprising. According to the proportionality doctrine, balancing is a necessary step of the doctrine to which the Court must turn when the challenged legislation has withstood the previous stages of the test. If the Court does not come to a different result at the balancing stage, however, the latter rather has a function of a plausibility test.Footnote 44 The more factors such a plausibility test includes, the more convincing it is. Normatively, it also does not pose any legitimacy challenges because the Court is simply confirming an act of the legislature. While such decisions might also be politically controversial, the Court cannot be accused of disrespecting the boundaries between the judicial and the legislative branch. Consequently, the balancing structure in this constellation is not necessarily representative of all balancing decisions.

E. Challenging the Legislature

It is quite telling that the decisions of the German Constitutional Court that Alexy cites in support of his theory of constitutional rights do not concern the last of our three constellations—that is, cases in which the Court finds a law to be incompatible with a constitutional right. If we have a closer look at these cases, it is easy to discern the reason. In the vast majority of decisions in which the Court declares a statute to be unconstitutional, the structure of the reasoning does not follow Alexy’s Law of Balancing. In the early years of its existence, the Constitutional Court mostly refrained from balancing when overturning a piece of legislation.Footnote 45 Moreover, even after the Court started to rely increasingly on balancing when challenging the legislature, the structure of the balancing test was noticeably different from the two constellations discussed in the previous section.

I have shown in an earlier study that the great majority of cases fall into one or more of the four categories discussed below.Footnote 46 This study was based on an analysis of all judgments in which the German Federal Constitutional Court declared a statute to be inconsistent with the constitution and in which it relied on the last step of the proportionality test. For this purpose, I looked through all decisions within the official law reports of the Constitutional Court. You can identify the cases in which a statute was declared to be unconstitutional by consulting the operative part of the decision. Then, I read all qualifying decisions in order to identify those in which the Court based its judgment on the last step of the proportionality test. The classification that I present in the following paragraphs is my own classification of the analyzed material.

The first category involves the Court often engaging in financial burden-shifting.Footnote 47 That is, it sanctions the legislative aim in principle but argues that the financial burden of the restraining measure must be borne by the State or a third party. The paradigmatic case for this type of reasoning is the Repository Copy decision.Footnote 48 The case concerned a statute of the state of Hesse, which required all publishers of this state to cede a free copy of every publication to specifically designated state libraries. In the case at hand, the applicant published expensive art catalogues in small print run. The Court argued that the burden on the publisher was excessive: While the State could require publishers to cede copies to state libraries to satisfy a public information interest, it had to compensate the publisher if the financial burden of the obligation was as significant as in the case at hand.Footnote 49 Consequently, the Court does not compare incommensurable values. Instead, it measures the burden of the applicant in financial terms and orders the State to pay compensation.

The second category involves the Court finding statutes to be disproportionate if the measure is inconsistent in pursuing the stated aim.Footnote 50 One example for such a consistency argument is a decision of the Constitutional Court regarding a provision of the German Civil Procedure Code.Footnote 51 The statute that was challenged required the publication of an incapacitation if the incapacitation was due to either dissipation or alcoholism.Footnote 52 The government argued that the publication was necessary to protect public trust in legal relations.Footnote 53 Yet, dissipation and alcoholism were not the only reasons for an incapacitation. Indeed, they made up only ten percent of all cases. The Court argued that the protection of public trust was not less important in all other cases.Footnote 54 That a publication of an incapacitation was nevertheless legally required only in cases of alcoholism and dissipation suggests that the real reason for the publication requirement was rather a stigmatization of the concerned individuals.Footnote 55 For this reason, the Court found the concerned rule to be disproportionate.Footnote 56 Again, the Court did not make a comparison of incommensurable values. Instead, it second-guessed the motives of the legislature by highlighting the inconsistency of the highlighted measure and argued that the true reason did not deserve sufficient respect to justify a restriction of the right to privacy of the concerned individuals.

The third category involved the German Constitutional Court declaring measures to be disproportionate if there is no sufficient fit between measure and purpose.Footnote 57 This category is basically a consequence of the strict reading of the less-restrictive-means stage of the proportionality test that the German Constitutional Court employs.Footnote 58 According to the interpretation of the German Constitutional Court, a measure fails at the less-restrictive-means stage only if there is an alternative measure that is less restrictive and equally effective as the measure under review. If there is doubt about the effectiveness of two alternative measures, the Court affords the legislature with a margin of appreciation. For this reason, a measure rarely fails the less-restrictive-means stage.

Nevertheless, the Court often returns to the question of fit at the balancing stage of the proportionality test. An example is the Hoof-Care decision of July 2007.Footnote 59 The statute under review required hoof caretakers and hoof technicians to have the same qualifications as farriers, who mastered a broader spectrum of hoof-care techniques than the former.Footnote 60 Yet, the Court argued that theoretical knowledge of the broader spectrum of hoof-care techniques was sufficient.Footnote 61 A hoof caretaker could always refer a horse to a farrier if they did not master the indicated caretaking technique. While the reasoning resembles a traditional less-restrictive-means argument, the Court resolved the case in the balancing stage. It could not exclude that requiring a broader qualification had some marginal benefits. It argued, however, that the burdens imposed by the requirement outweighed any potential marginal benefits. This third category where the Court analyzes the fit between measure and purpose in the balancing test therefore resembles the Canadian Supreme Court’s approach to the less-restrictive-means test.Footnote 62

The fourth category involves the German Constitutional Court filtering out cases of individual hardship on the balancing stage.Footnote 63 In these cases, the Court accepts the legislative decision in principle but carves out an exception for a group on which the challenged measure imposes a particular burden. An example of this type of reasoning is the already mentioned Repository Copy decision.Footnote 64 In this decision, the Court asked the legislature to compensate publishers for the obligation to cede a copy of each publication to the State library.Footnote 65 The Court, however, did not require a general compensation for all ceded copies. Instead, it imposed the compensation requirement only for cases in which the obligation put a particular financial burden on the publisher because of the high production costs for each individual volume.Footnote 66

In all of these four categories of cases, the German Constitutional Court does not rely on a comparison of incommensurable values as is suggested by Alexy’s weight formula. Instead, the reasoning is much more restrictive. In the burden-shifting cases, the Court sanctions the legislative aim, but requires the legislature to pay compensation for imposing a financial burden on individuals to achieve a public goal. In the consistency cases, the Court indirectly second-guesses the motives of the legislature by highlighting inconsistencies in the conception of the legislation.Footnote 67 When the Court denies a fit between measure and purpose, it basically employs a less-restrictive-means kind of reasoning that is similar to what other courts—like the Canadian Supreme Court—do in the less-restrictive-means stage. The category that comes closest to comparing incommensurable values is the last: The correction of cases of individual hardship. Yet, in these constellations, the Court usually carves out only narrow exceptions for particular groups without questioning the legislative aim in general. Therefore, the decisions of the Constitutional Court do not impose significant costs on the legislature. In fact, they are often arguably in the interest of the legislature if it has overlooked that a measure would impose a particular hardship on a small group of people.Footnote 68

While these four categories comprise more than eighty-five percent of all balancing decisions in which the German Constitutional Court declares a law to be incompatible with constitutional rights, there are some decisions in which the Court uses balancing in a way that rather resembles Alexy’s Law of Balancing: The Court finds that the pursued public purpose does not carry sufficient weight to justify the restriction of the affected constitutional right. Almost all of these cases concern criminal law or criminal procedure provisions.Footnote 69 But again, the Court exercises self-restraint in these decisions: It never challenges the main purpose of the legislation as such, but imposes only corrections at the margins.Footnote 70 For example, it generally sanctions a criminal procedure measure, but marginally restricts the list of crimes for which the challenged measure can be initiated.

Taking Alexy’s Law of Balancing at face value has often triggered the fear that balancing could become a powerful instrument to second-guess legislative value decisions. If we look at the practice of the German Constitutional Court, however, the judges exercise considerable self-restraint. In most cases, the structure of the balancing test applied does not resemble Alexy’s Law of Balancing, but rather resorts to different argumentation patterns. Even where the Court engages in a weighing of competing aims, the decisions usually do not challenge the main purpose of the legislation, but instead restrict themselves to corrections at the margins.

F. A Modest Defense of Proportionality

By overstating the defense of proportionality, Alexy actually weakens the normative case for proportionality rather than strengthening it. For this reason, Christoph Engel once called Alexy a forceful critic of proportionality in disguise.Footnote 71 Nonetheless, discarding proportionality for the reason that some theoretical conceptions of balancing might give courts too much political discretion would throw out the baby with the bathwater. Certainly, proportionality has its analytical flaws. In particular, the balancing stage requires the comparison of incommensurable values, for which we lack suitable normative standards.

This does not mean, however, that balancing is necessarily irrational. It only means that judges enjoy a considerable amount of discretion when they balance. Yet, judicial discretion is not unique to balancing.Footnote 72 This contribution has analyzed the reasoning of the German Federal Constitutional Court in balancing cases and examined whether Alexy’s Law of Balancing offers a proper reconstruction of the Court’s reasoning structure. We have seen that Alexy’s account captures balancing decisions on two constellations adequately. Both in horizontal rights cases and in cases in which the Court confirms challenged legislation, the balancing step usually resembles Alexy’s weight formula: The judges weigh competing interests and take into account the extent to which these interests were promoted or restricted.

Nevertheless, the reasoning structure changes when the Court relies on balancing when declaring a statute to be unconstitutional. It usually does not weigh the competing aims against each other, but bases its arguments on much narrower grounds. Therefore, Alexy’s theory of constitutional rights does not provide an adequate reconstruction of balancing decisions in this last constellation. Yet, arguably, the latter is politically the most sensitive one because it leads to a conflict between the Constitutional Court and the legislature, which is absent in the other two constellations. This means that even if the judges of the German Federal Constitutional Court enjoy discretion when they are balancing, they have—so far—exercised their discretion responsibly and shown self-restraint.Footnote 73 This is certainly no watertight normative defense of proportionality. But it underlines the flexibility of the doctrine and shows that it does not necessarily lead to a strict or searching standard of review as some critics fear.Footnote 74