A. Introduction

UN human rights treaty bodies have been under constant review within the framework of the UN in an attempt to improve their effective functioning,Footnote 1 and stakeholder participation has always been treated as one of the critical issues in these reviews.Footnote 2 The final report of the “2020 review,” conducted based on UN General Assembly Resolution 68/268 titled “Strengthening and enhancing the effective functioning of the human rights treaty body system” (2014), reiterated “the integral role that civil society, national human rights institutions and academic platforms play in the engagement with the treaty bodies.”Footnote 3 Treaty bodies have implemented multiple reforms to promote such participation (see Section B). Today, their websites, run by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), commonly display an index titled “Participation: Information for civil society, NGOs and NHRIs”Footnote 4 and provide detailed information on their participation.

In these discussions and reforms, non-governmental organizations (NGOs)Footnote 5 and national human rights institutions (NHRIs) have largely been lumped together and treated in parallel. This approach is understandable as both NGOs and NHRIs interact with treaty bodies as independent actors from states. They are new actors in the eyes of traditional, state-centric international law. The former challenges its fundamental assumption that states are the only relevant legal entities under international law,Footnote 6 and the latter challenges its perception of “states” as unitary and monolithic legal entities.Footnote 7 However, although there are several detailed studies on NGOFootnote 8 and NHRI participationFootnote 9 in treaty body activities, few studies have focused on the qualitative difference between the two.Footnote 10 NGOs were the pioneers that paved the way for stakeholder participation in the work of treaty bodies. When NHRIs emerged as human rights treaty actors in the 2000s, following in the NGOs’ footsteps, studies posited that the sui generis character of NHRIs is distinct from that of NGOs owing to the former’s official human rights mandate under national lawsFootnote 11 and described them as a “third type of actor” between states and NGOs.Footnote 12 However, although studies have stressed the unique roles of NHRIs as state organs in the context of the implementation of treaty bodies’ recommendations,Footnote 13 they failed to establish the added value of NHRIs’ provision of inputs to treaty bodies as distinct from those of NGOs.Footnote 14 They considered that the NHRIs’ participatory roles “largely concur”Footnote 15 with those of NGOs and that NGOs’ functions are “supplemented” by NHRIs.Footnote 16 Some have negatively reflected on the added value of NHRI participation.Footnote 17 Whereas one has suggested that the “legitimacy [of NHRI submissions] can be higher than that of NGOs, since [NGOs] might be driven by very specific interests,”Footnote 18 there is a contradicting observation that NGOs have greater autonomy and independence than do NHRIs and thus “NHRIs have a more limited function than NGO networks.”Footnote 19 Fiona McGaughey emphasized the need for “further exploration of the role of NHRIs vis-à-vis NGOs.”Footnote 20

Against this background, this article addresses the following question from normative and empirical perspectives: “Are the roles and values of stakeholder participation in UN human rights treaty body activities qualitatively different for NGOs and NHRIs, and if so, how?” This question is not an end in itself. It opens a window toward a more profound, underexplored theoretical question: what precisely are the values brought by stakeholder participation to treaty body activities? Many previous studies have taken the benefit of stakeholder participation for granted. However, several studies have argued that it can supplement the treaty bodies’ lack of an independent fact-finding capabilityFootnote 21 by providing them with “on-the-ground” and “first-hand” information.Footnote 22 Some studies have observed that their participation can “sensitize” treaty bodies,Footnote 23 “maintain the balance of information,”Footnote 24 assist treaty bodies “to double-check” state submissionsFootnote 25 and “to find persuasive legal interpretations,”Footnote 26 draw their attention to “the periphery,”Footnote 27 and offer “expertise”Footnote 28 and “cultural translation”Footnote 29 to these bodies. Other studies have emphasized its contribution to inclusion,Footnote 30 democratic decision-making,Footnote 31 the legitimacy of human rights treaties, subsidiarity,Footnote 32 and the legitimacy of international law from the discourse theory perspective.Footnote 33 Nevertheless, the comprehensive picture of the rationale for stakeholder participation has not been presented; these studies focused solely on one type of stakeholder (primarily NGOs) and/or on one type of treaty body activity (mostly state reporting procedures) or made generalized statements without defining the scope of their applicability. These various rationales have not been systematized. Moreover, whether and how different weights should be given to those rationales, especially based on the type of stakeholder and treaty body activity concerned, has not been explored.Footnote 34 Thus, this article fills the aforementioned gaps in the literature by “dissecting” stakeholder participation, differentiating between NGO and NHRI participation, and analyzing their respective values in different treaty body activities.

The research question has major practical importance when seen from two perspectives. First, in recent years, the “flood of information” provided to treaty bodies constituted a challengeFootnote 35 that required prioritization among those inputs.Footnote 36 Thus, by finding the unique strengths and advantages of NHRIs’ and NGOs’ participation in treaty body activities, this article contributes to the maximum exploitation of their benefits, which can enhance the effectiveness and legitimacy of treaty bodies and the efficient use of the limited time and resources of treaty bodies.Footnote 37 Second, one reason for the reluctance of some established democracies to create NHRIs, despite repeated calls from international human rights bodies, is that they question the benefit of NHRIs, given that active NGOs work in their countries.Footnote 38 This article offers a rebuttal by showing the added value of NHRI participation in treaty body activities.

To this end, as a preliminary observation, this article summarizes the historical and current institutional frameworks for the participation of NHRIs and NGOs in treaty body activities (Section B). Second, it normatively analyses the respective values backing NGO and NHRI participation, in each type of treaty body activity, based on three rationales for stakeholder participation: facilitating “bounded” deliberations at the national level, promoting deliberations on human rights treaty standards at the international level, and supplementing treaty bodies’ weak fact-finding capacity. It offers concrete normative guidance for treaty bodies on their engagement with NGO and NHRI participation in their different activities (Section C). Finally, it conducts an empirical study on the weight treaty bodies have granted to NGO and NHRI inputs and examines the extent to which such practice conforms to this article’s normative guidance (Section D).

Regarding this article’s terminology, scope, and limitations, first, it defines NGOs as “organizations not established by a government or by way of intergovernmental agreement, that are freely created by private initiatives and not profit-seeking.”Footnote 39 Although different typologies exist for NGOs, this article focuses on two axes: the geographical scope of the NGO’s membership and activities and the general or specific scope of their mandate. For example, Amnesty International is an international NGO with a general human rights mandate, whereas the Forum for Refugees Japan is a local NGO with a specific mandate. Nevertheless, this categorization is blurred when NGOs act collectively in an ad-hoc manner or under umbrella organizations and networks. Although the UN Economic and Social Council has established a system of accrediting NGOs,Footnote 40 its criteria and procedures are unsuitable for human rights treaty body activities. Thus, treaty bodies have not relied on them,Footnote 41 nor does this study, when addressing NGO participation in treaty body activities. This article defines NHRIs as “state organs with constitutional and/or legislative mandates to protect and promote human rights,”Footnote 42 encompassing all types of NHRIs, namely commissions, ombudsman institutes, hybrid institutions, consultative and advisory bodies, research institutes and centers, civil rights protectors, public defenders, and parliamentary advocates.Footnote 43 Despite this broad definition of NHRIs, to acquire A-status from the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI), NHRIs should fulfill additional requirements based on the Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (“Paris Principles”) and the General Observations prepared by the GANHRI’s Sub-Committee on Accreditation (SCA), especially those requirements concerning independence, pluralism, and effectiveness.Footnote 44 Second, this study focuses on the three UN human rights treaty bodies with the most extensive history of work and the richest experiences at the time of writing, namely the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), established under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD); the Human Rights Committee (HRC) under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Convention). Third, this study focuses only on the three main activities of the three UN human rights treaty bodies: state reporting and individual communications procedures, and the production of general comments/recommendations. It evaluates the participation and provision of inputs by NGOs and NHRIs in these procedures rather than their contributions toward implementing the treaty bodies’ recommendations. Fourth, although this study drew out normative observations on how treaty bodies should treat NGOs and NHRIs, it does not offer proposals on the concrete and detailed modalities and practicalities concerning their participation. It only serves as evidence for such decision-making.

B. Institutional Frameworks for the NGO and NHRI Participation

The participation of NGOs and NHRIs was initially developed in the context of each established procedure (sectoral approach) (I). However, since around 2010, treaty bodies have supplemented this approach comprehensively and holistically by producing papers and guidelines to regulate NGOs’ and NHRIs’ participation as a whole (II).

I. Sectoral Approach: Evolution of NGOs’ and NHRIs’ Participation in Treaty Body Procedures

1. State Reporting Procedure

As a mandatory procedure for all state parties, the state reporting procedure constitutes the principal monitoring mechanism for the treaty bodies. In this procedure, state parties submit initial reports within a specified period after the treaty enters into force and provide periodic reports to the treaty bodies thereafter. Treaty bodies examine those reports in a public meeting where state delegations are invited for a “constructive dialogue.” Since the 1990s, treaty bodies have begun addressing “concluding observations” to each state party after examining its report.

Treaty bodies lack an independent fact-finding capability. Relevant treaty provisions, such as Article 40 of the ICCPR, are silent on the source of information that treaty bodies are entitled to rely on in examining state reports. Thus, as soon as treaty bodies were activated, a fierce debate emerged on the admissibility of information emanating from external sources, including NGOs.Footnote 45 As treaty bodies were initially reluctant to recognize or institutionalize NGO involvement given the skepticism of some (mainly Eastern) members against the use of external sources in generalFootnote 46 and the allegedly anti-Second and Third World nature of NGOs in particular,Footnote 47 the roles of NGOs were confined to contacting treaty body members unofficially and in their individual capacity, not through the Secretariat.Footnote 48 Treaty body members were advised not to refer to NGO documents or mention their names when examining state reports.Footnote 49 Nevertheless, in the 1980s, NGOs gradually acquired trust and expanded influence; even Eastern members occasionally began to rely expressly on NGO information.Footnote 50 Partly because of the alleviation of the East-West divide within treaty bodies after the Cold War, NGO participation in state reporting procedures was officially recognizedFootnote 51 and institutionalized in the 1990s.Footnote 52

NHRIs were latecomers vis-à-vis engagement with treaty bodies.Footnote 53 The turning point that led to their entry was the adoption of the Paris Principles in 1991Footnote 54 and the endorsement of these Principles in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of ActionFootnote 55 and by the UN General AssemblyFootnote 56 in 1993, which have extensively promoted the rapid growth of NHRIs worldwideFootnote 57 and their recognition as independent human rights actors.Footnote 58 The status of NHRIs in the state reporting procedureFootnote 59 was initially unstable,Footnote 60 as treaty bodies have occasionally treated them as part of government delegations.Footnote 61 However, since 2000s, NHRIs have gradually commenced interacting with treaty bodies in their own right.Footnote 62 In the fourth Inter-Committee Meeting of Human Rights Treaty Bodies in 2005, the participants agreed to develop “harmonized criteria for the participation of [NHRIs] in treaty body sessions in order to enhance the quality of information provided to the treaty bodies.”Footnote 63 Around that time, treaty bodies amended their procedures to expressly authorize NHRIs to provide information to their members in the same manner as NGOs.Footnote 64

Today, both NGOs and NHRIs can submit written reports and address treaty body members in formal and informal meetings before preparing lists of issues and examining state reports.Footnote 65 The modalities for such participation are widely publicized as “NGO information note” and “NHRI information note,” which are posted on treaty bodies’ websites in advance of the session. Most modalities, such as the submission deadline, word limit, and venue, are common between NGOs and NHRIs.Footnote 66 Nevertheless, a crucial difference is that the CERD and CEDAW permit A-status NHRIs to present oral statements during constructive dialogues with state parties.Footnote 67

2. Elaboration of General Comments/Recommendations

General comments (HRC) and general recommendations (CERD and CEDAW) are today known as non-binding guidance on specific treaty provisions and/or the relationship between treaty provisions and specific themes. They do not concern specific situations and states and are addressed to all state parties in general. Treaty provisions remain silent on the procedure for adopting general comments/recommendations. However, as such documents developed into “substantial and highly detailed commentaries on each aspect of a given article,”Footnote 68 especially after the Cold War, stakeholder participation became vital for their legitimacy.Footnote 69 Thus, in 1997, the CEDAW adopted a decision stating that NGOs are encouraged to participate in the discussion on draft general recommendations and to prepare informal background papers.Footnote 70 Other treaty bodies followed suit.Footnote 71 While NGOs have been the primary participants, several NHRIs have also been involved. Since the 2000s, treaty bodies have posted invitations for stakeholder comments on draft general comments/recommendations,Footnote 72 and since the 2010s, they have made these comments publicly available on their websites.Footnote 73

In 2021, the CERD adopted “Guidelines on the elaboration of general recommendations” to formalize stakeholder participation,Footnote 74 broadly representing common practice among treaty bodies.Footnote 75 The guideline states that stakeholders, including NGOs and NHRIs, may engage in their elaboratation in various ways, such as suggesting relevant topics for elaborating general recommendations,Footnote 76 and providing inputs in days of general discussionsFootnote 77 and on the first draft posted on the CERD’s webpage.Footnote 78 For example, before drafting General Recommendation No. 36 (2020) on preventing and combating racial profiling by law enforcement officials, the CERD held a thematic discussion on “Racial discrimination in today’s world: Racial profiling, ethnic cleansing, and challenges” in 2017. A background note was circulated to invite stakeholders to participate;Footnote 79 22 NGOs and 1 NHRI made statements in the discussion, along with state delegations and UN experts.Footnote 80 When the CERD produced the Draft General Recommendation No. 36 in 2019, it invited all stakeholders to send in their comments, which led to submissions by 15 NGOs and 9 NHRIs, among other stakeholders.Footnote 81

3. Individual Communications Procedure

The individual communication procedure is optional, unlike the state reporting procedure. For those state parties that accepted the treaty bodies’ competence, treaty bodies may receive and consider individual communications alleging a violation of the human rights enshrined in the respective treaties. At the end of this quasi-judicial procedure, treaty bodies issue “Views” (HRC and CEDAW) or “Opinions” (CERD), which contain their findings on the existence or otherwise of a violation and, if necessary, provide recommendations for a remedy. The provisions concerning the locus standi for individual communications are termed differently in the three treaties. Whereas the Optional Protocol to the ICCPR limits the authors of communications to “individuals” who claim to be victims (Articles 1 and 2), the CERD can receive communications from “individuals or groups of individuals” (Article 14 of the ICERD) and the CEDAW can receive communications submitted “by or on behalf of individuals or groups of individuals” (Article 2 of the Optional Protocol to the CEDAW Convention). The broader scope established in the Optional Protocol to the CEDAW Convention was the outcome of a compromise between those who had emphasized the indispensable roles of NGOs as authors of communications given “the obstacles women may face in seeking remedies, including danger of reprisals, low levels of literacy and legal literacy and resource constraint,”Footnote 82 and those concerned with the abuse of such roles.Footnote 83

NGOs have participated in individual communications procedures through four channels: (i) acting as representatives of victims with their consent; (ii) submitting communications on behalf of victims without their consent when they are unable to communicate on their own; (iii) submitting communications as victims of violations suffered on their own and/or by their own members; and (iv) submitting briefs as third parties/amicus curiae.Footnote 84 The first type is the most common and uncontested form of NGO participation.Footnote 85 It has been utilized since the early days,Footnote 86 as the treaties do not restrict the qualification of representatives.Footnote 87 In rare cases, NHRIs have represented victims.Footnote 88 Regarding the second pattern, according to the implicit intention of the drafters embedded in the term “on behalf of’ the victims” mentioned above, the CEDAW has permitted NGOs to serve as communications authors.Footnote 89 In V.C. (deceased) v. Moldova in 2020, given that the author NGO could not have obtained the victim’s consent owing to her death, that she was an orphan with no next of kin, that she had been paralyzed, and that the NGO had obtained consent from her closest friend and executor of her will, the CEDAW admitted the communication “in the interest of justice and the prevention of impunity.”Footnote 90 Even without a comparable phrase within the text of the treaties, the HRC and CERD have recognized submissions on behalf of victims without their consent as long as “the author(s) can justify acting on their behalf without such consent.”Footnote 91 However, given the strict application of these requirements, they have mostly denied NGOs the opportunity to serve as representatives in this sense.Footnote 92 Treaty bodies are divided on the admissibility of the third pattern. Whereas the HRC has been reluctant to admit the locus standi of legal persons, including NGOs based on the term “individuals” in the above-mentioned provision,Footnote 93 the CERD and CEDAW have not precluded the admissibility of NGO submissions based on the term “individuals or group of individuals.”Footnote 94 Nevertheless, these bodies are careful not to allow actio popularis in substance under the disguise of NGOs’ submissions as victims.Footnote 95 Whereas the three channels mentioned above permit NGOs and NHRIs to pursue individual victims’ redress, the fourth channel allows them to act more flexibly by representing arguments, interests, and perspectives strategically or unintentionally overlooked by the parties, to enhance public interest and promote broader mobilization for structural reforms.Footnote 96 The CEDAW was the pioneer in admitting third-party/amicus curiae interventions,Footnote 97 and the HRC and CEDAW both adopted guidelines on third-party intervention.Footnote 98 Nevertheless, their approaches differ in that the former permits “autonomous” third-party interventions (those without authorization by one of the parties to the dispute) while the latter requires authorization.Footnote 99 Treaty bodies face multiple and increasing third-party NGO interventions, including those currently pending.Footnote 100 The CERD is the first and only body to have admitted an amicus curiae brief by an NHRI.Footnote 101

II. Comprehensive and Holistic Approach: Current Institutional Frameworks Governing the Participation of NGOs and NHRIs

Since around 2010, treaty bodies have taken a comprehensive approach toward regulating NGOs’ and NHRIs’ participation across all activities, thus supplementing the sectoral approach. In 2011, the HRC held a meeting with NGOs and NHRIs to consider ways to improve their cooperation with the HRC,Footnote 102 which resulted in the adoption of papers on its relationship with NGOsFootnote 103 and NHRIs,Footnote 104 respectively, in 2012. The CERD adopted guidelines for cooperation with NGOsFootnote 105 and NHRIsFootnote 106 in 2021. The CEDAW adopted a statement on its relationship with NHRIs in 2008,Footnote 107 produced a paper on cooperation with NHRIs in 2019,Footnote 108 and made a statement on its relationship with NGOs in 2010.Footnote 109 The adoption of these documents symbolizes treaty bodies’ recognizing them as autonomous actors that should be regulated in a unified manner instead of a patchwork fashion. The fact that NGO and NHRI participation is dealt with in separate documents demonstrates that treaty bodies consider them distinct entities.Footnote 110 The HRC’s paper on its relationship with NHRIs states that:

[NHRIs] have an independent and distinct relationship with the Committee. The relationship is different from, yet complementary to, those of State parties, civil society, non-governmental organizations and other actors. Accordingly, the Committee provides ICC [today’s GANHRI]-accredited national human rights institutions with opportunities to engage with it that are distinct from those of other actors.Footnote 111

Other treaty bodies have adopted similar formulae.Footnote 112 However, the HRC’s papers do not mark a substantial difference in the treatment of NGOs and NHRIs. By contrast, the other two bodies give NHRIs greater opportunities for participation. In the state reporting procedure, they offer A-status NHRIs an opportunity to present an opening statement during a formal dialogue with the state party.Footnote 113 The CEDAW expressly encourages NHRIs to provide it with reliable and evidence-based information in individual communications procedures,Footnote 114 whereas it does not do so for NGOs.

C. Normative Analysis: Three Values of Stakeholder Participation

The values brought by stakeholder participation in treaty body activities are categorized into the following three components: (I) facilitating “bounded” deliberations at the national level, (II) promoting deliberations on human rights treaty standards at the international level, and (III) supplementing treaty bodies’ weak fact-finding capacity. Whereas (III) corresponds to what many studies have referred to as “supplementing the treaty bodies’ fact-finding capability,” (I) and (II) integrate and reconstruct what previous studies have described under various other concepts (see the Introduction) so that these values can function as normative frameworks guiding the treaty bodies’ practice on stakeholder participation in a comprehensive manner. These three values carry different weights for the differing activities of treaty bodies. First, for the state reporting procedure, (I) and (III) mainly apply directly. Second, for elaborating general comments/recommendations, (II) applies. Third, for the individual communications procedure, (III) concerns the fact-finding phase, and (I) applies to the phase involving the application of the treaty standards to the specific facts of the case, especially while having to balance the rights and interests involved. As regards the treaty interpretation phase, especially when evolutive interpretation is concerned, (II) applies.

I. Facilitating “Bounded” Deliberations at the National Level

This value is based on the author’s theory of the “two-tiered bounded deliberative democracy.”Footnote 115 Given that democratic legitimacy challenges against human rights treaties have become serious owing to the increasing intrusion of human rights treaties into national legal orders, and because the international community has come to share a denser conception of democracy, this theory builds on the notion of deliberative democracy to harmonize human rights protection and democracy at the global level. It posits that we live in globalized democratic societies comprised of two tiers of deliberations: national and international. In this theory,

[D]eliberations should primarily take place within each national society, as only national societies are equipped with dense public spheres, sufficiently shared values, and approximately equal stakes, which are preconditions for rich and meaningful deliberations. However, deliberations in national societies inevitably suffer from some deficits …. To address this gap, … “bounds” on national deliberations should be established through long-term and matured deliberations at the international level.Footnote 116

The value of facilitating “bounded” deliberations at the national level corresponds to the first tier of deliberations within this theory. Human rights treaty standards should primarily be realized through national deliberations, where local conditions and needs are considered within the framework of human rights treaty standards and affected individuals, including minorities, are represented most effectively. To enable such deliberations, human rights treaty standards must be embedded in national formal and informal public spheres. Treaty bodies must respect and facilitate such deliberations. The state reporting procedure and the treaty application phase in the individual communications procedure provide opportunities to respect and facilitate “bounded” deliberations at the national level, especially where they involve a review of the balancing exercise between rights and interests, which is particularly apt for decisions based on national deliberations.

As Jürgen Habermas posited, deliberative democracy can function properly and be a source of political legitimacy only with continuous interaction between the two processes of deliberation (“two-track model”): non-institutionalized deliberations in the informal public sphere, where civil society is situated in its core;Footnote 117 and institutionalized deliberations in the formal public sphere in the political system such as the parliament and court.Footnote 118 The former constitutes a locus for an open-ended debate on all sorts of issues, political and otherwise.Footnote 119 It serves as a “context of discovery”Footnote 120 - sensitively detecting new problem situationsFootnote 121 as “a sounding board.”Footnote 122 The latter serves as the “context of justification,”Footnote 123 where deliberations are conducted under pressure to decide within restricted forms, procedures, time, and reasons, leading to binding decisions.Footnote 124 The quality of the deliberations in the formal public sphere depends mainly on the supply of public opinions generated in the informal public sphere.Footnote 125 However, the active interplay between these processes of deliberations is often hampered by the fact that “the signals [that movements and initiatives within the civil society] send out and the impulses they give are generally too weak” to reach the formal public sphere in the short run.Footnote 126

Against this background, NHRIs, especially those with A-status, can serve as a unique bridge between the two processes of deliberations. The Paris Principles and the SCA’s General Observations require NHRIs to collaborate closely with civil society in terms of their composition and activities, thus reaching “sections of the populations who are geographically, politically or socially remote” and “engag[ing] with vulnerable groups,”Footnote 127 while advising the national parliament, the government, and the court actively and regularly.Footnote 128 Given their broad human rights mandate and their resultant “home-made” human rights expertise,Footnote 129 they can ensure that national deliberations are properly “bounded”—conducted within the framework of human rights treaty standards—without neglecting local values and realities. This way, A-status NHRIs, which largely fulfill the above-mentioned requirements under the Paris Principles and the General Observations, are located at the pivot of bounded national deliberations. Accordingly, their views should enjoy special weight as a reflection of such deliberations. Thus, the opportunity for A-status NHRIs to make oral statements during the constructive dialogue should be encouraged for its symbolic effect in empowering NHRIs vis-à-vis their national governments and civil society. Furthermore, citing NHRIs’ views is desirable, both in constructive dialogue and concluding observations in the state reporting procedure and in Views or Opinions in the individual communications procedure. By doing so, treaty bodies can signal respect for and facilitate bounded national deliberations instead of imposing their own value judgements from outside.Footnote 130 Treaty bodies should consider requesting NHRIs on their own initiative to intervene as third parties in individual communications procedures for appropriate cases.Footnote 131

By contrast, international NGOs, which are outsiders and distanced from the national society, have little place in national deliberations, in principle.Footnote 132 Local NGOs that are part of national civil society have an avenue to engage in national deliberations by lobbying the political systems; such voices should primarily be considered and addressed by national political systems rather than directly by treaty bodies in a manner that circumvents the national deliberative process.Footnote 133 Therefore, when bounded national deliberations appear to work well, treaty bodies should refrain from giving substantial and decisive weight to NGOs’ views, as that would upset the balance of rights and interests that have been or that should be delicately achieved through national deliberations. However, local NGOs can catalyze treaty bodies’ intervention when bounded national deliberations are dysfunctional. Local NGOs may provide treaty bodies with the views, positions, and perspectives that have not been properly taken up in the political system, based on which treaty bodies give guidance on the orientations for bounded national deliberations.Footnote 134

II. Promoting Deliberations on Human Rights Treaty Standards at the International Level

This category corresponds to the second tier of deliberations, namely international deliberations within the ambit of the “two-tiered bounded deliberative democracy.” In this theory, human rights treaty standards, which restrict and guide national deliberations as “bounds,” must be developed based on thorough deliberations at the international level where a more comprehensive range of positions and interests are heard and considered, including those that are overlooked and ignored in national deliberations.Footnote 135 Given the absence of a centralized political body at the international level, treaty bodies must proactively serve as a forum for deliberation where treaty standards are adapted and evolutively interpreted in light of social change and accompanying needs. This value applies to the elaboration of general comments/recommendations, most directly, where treaty bodies substantially produce new human rights norms in a general manner,Footnote 136 thus assuming a lawmaking function.Footnote 137 It concerns the individual communications procedure when treaty bodies develop new standards based on evolutive interpretation.Footnote 138

From the perspective of promoting international deliberations, the identity of the stakeholders is not as important as the actual diversity of opinions, positions, and perspectives brought into the deliberations by their participation. The CERD has stated in its Guidelines on the Elaboration of General Recommendations that stakeholder participation aims to provide the Committee with a “wider spectrum of views on the subject matter, encompassing as many relevant issues as possible.”Footnote 139 Thus, the roles and values of NGO and NHRI participation do not differ qualitatively for this purpose. For the same reason, the values of their participation are not distinguishable from that of state parties for this particular purpose, even though the traditional rules of treaty interpretation codified in the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties accord a privileged status for state parties (see especially, Article 31 (3) (a) and (b)).

That said, NGOs, especially international ones with specific expertise on the subject matter of a given general comment/recommendation, hold a relative advantage over NHRIs in playing a role as they have the most updated and comprehensive data, information, and knowledge on the matter, including relevant international standards and practice and challenges common in various states and regions. Many such NGOs are fully acquainted with the relevant jurisprudence of regional human rights courts and national legislation and jurisprudence. They can assist treaty bodies, which chronically lack human resourcesFootnote 140 and are often dominated by non-international lawyers,Footnote 141 to cover such material. Thus, treaty bodies can promote international deliberations on human rights standards by considering the information and views of such NGOs. Moreover, the active transnational communications led by international NGOs contribute to the emergence of the “transnational” public sphere and deliberations,Footnote 142 which can enrich the quality of international deliberations. Thus, treaty bodies should not hesitate to cite and name the NGOs they consulted. The fact that they have consulted a wide range of NGOs positively affects the democratic legitimacy, within the meaning of the “two-tiered bounded deliberative democracy,” of the resultant human rights treaty standards.

By contrast, a general assumption exists that NHRIs play limited roles in international deliberations, as the information and views provided by NHRIs tend to focus on the national situations of a particular state, owing to their national scope of mandate. Nevertheless, where some states and regions are especially affected by the subject matter but are inadequately covered by international NGOs, NHRIs can fill the gaps. NHRIs may contribute more to international deliberations by acting collectively, just like NHRIs in Europe, which have actively and regularly made third-party submissions to the European Court of Human Rights collectively to provide the Court with detailed comparative law data.Footnote 143

III. Supplementing the Treaty Bodies’ Weak Fact-Finding Capacity

The treaty bodies’ lack of independent fact-finding capacity, including its lack of expertise in national legal systems and jurisprudence, constitutes a weakness for the effective functioning of state reporting and individual communications procedures.Footnote 144 In the former, the state parties under review tend to present a favorable version of the relevant information or submit a very descriptive report on the state of the law.Footnote 145 For treaty body members to pose questions and comments and issue concluding observations that properly reflect society’s current human rights realities and priorities, they require access to the most updated, detailed, and objective information. In the latter, although treaty bodies normally defer to the fact-finding and the interpretation and application of national laws by national courts in the absence of procedural irregularities and manifest arbitrariness,Footnote 146 cases occur where national judgments do not cover disputed facts or the independence of the national court itself is under dispute. Unlike the International Court of Justice or other international judicial bodies that ensure that a judge of the nationality of each party to the dispute is present on the bench, treaty bodies exclude members of the same nationality to ensure impartialityFootnote 147 and thus do not benefit from the national expertise of such members.

From this perspective, NGOs, especially the local and grassroots ones, have the most significant advantage because they have the latest and most detailed information on a particular issue or case. Nevertheless, they have several weaknesses. First, without a centralized evaluation system for NGOs like the GANHRI, it is difficult to objectively determine whether and to what extent the NGO concerned is reliable.Footnote 148 Second, some states have few local NGOs that can report grassroots information.Footnote 149 Although international NGOs often supplement such a gap, they are selective,Footnote 150 and overreliance on them would create a perception of “human rights imperialism.”Footnote 151 Third, NGOs risk intimidation and reprisals in some countries for acting against the government.Footnote 152 Therefore, treaty bodies and their members should refrain from citing the information provided by a single NGO in a definitive manner. However, they can rely on NGOs’ information wherever such information converges. They should avoid naming the NGOs as it may create a controversy on the reliability of the NGO in questionFootnote 153 and enhance the risk of intimidation and reprisals it may face.

By contrast, NHRIs with A-status have the guarantee that they largely comply with the Paris Principles and the SCA’s General Observations, including the criteria of independence, pluralism, and effectiveness.Footnote 154 They are presumed to have the mandate under national law to obtain statements or documents and inspect and examine any public premises, documents, equipment, and assets.Footnote 155 Thus, they have access to information that NGOs do not. As A-status NHRIs are supposed to collaborate closely with national NGOs, information from the latter should be appropriately integrated into that of the former. Additionally, as A-status NHRIs are mandated to monitor human rights situations of a given state continuously, covering all categories of human rights,Footnote 156 they must have a precise understanding of the human rights realities and priorities in the state concerned and the context in which the given human rights issue is situated. Therefore, the information provided by A-status NHRIs has sufficient reliability and authority. The other distinctive feature of NHRIs is that they are state organs. States endorse their NHRIs’ independence and credibility. Treaty bodies’ direct and express reliance on NHRIs’ information is unlikely to be challenged by states.Footnote 157 Nevertheless, because NHRIs are state organs, they may be incentivized to keep their criticism to a tolerable level. Also, as many NHRIs, including those with A-status, struggle for richer resources, they may be unable to cover all issues and cases.

D. Empirical Analysis: Do Treaty Bodies Give Different Weights to NGOs and NHRIs?

I. State Reporting Procedure

Although previous studies have examined the impact of NGO and NHRI participation in the examination of state reports, they are primarily anecdotal based on personal experienceFootnote 158 and do not provide an objective and overall picture. Some studies have conducted documentary and linguistic matching analyses between NGO/NHRI recommendations and treaty bodies’ concluding observations.Footnote 159 However, these methodologies cannot fully trace the causal link between participation and outcome. As treaty body members may rely on sources outside of those submitted by NGOs and NHRIs,Footnote 160 including documents from the previous reporting cycle, the probability that matches are merely coincidental cannot be excluded. Thus, this article adopts a methodology that focuses on the direct reference to the source by treaty body members, which uncontestably shows that the source made a decisive impact and/or that the treaty body members considered the sources worth mentioning for their credibility and authority. The current study focuses on the summary records of the constructive dialogue in the state reporting procedure in the three latest sessions of each treaty body. It examines when and how often treaty body members expressly relied on NGO or NHRI information and views to ask questions, request information, or make recommendations.

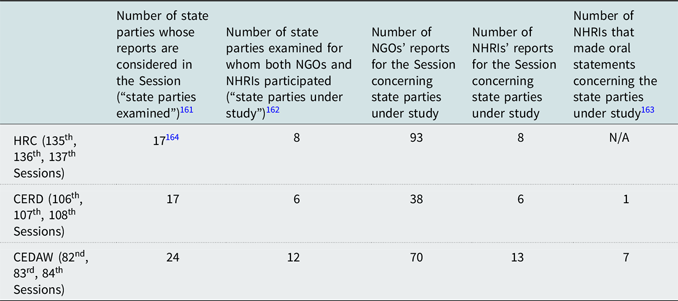

Table 1 shows the statistics concerning the participation of NGOs and NHRIs in the sessions under study. Whereas NGO reports have been submitted for almost all state parties examined, NHRI reports have been submitted for only around half of the states. Therefore, to directly compare their participation under identical conditions, among the state parties whose reports are considered in the sessions (“state parties examined”), only those for whom both NGOs and NHRIs have submitted reports and/or have made oral statements (“state parties under study”) are studied. From the normative perspective of facilitating “bounded” national deliberations, the fact that few NHRIs have exploited opportunities to make oral statements is regrettable (see Section C-I ).

Table 1. NGO and NHRI participation

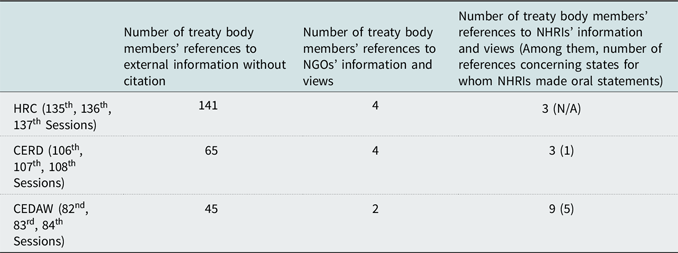

Table 2 shows the number of direct references by treaty body members to NGO and NHRI submissions within the summary records of the constructive dialogue with the state parties under study. Treaty body members have often resorted to external sources while asking questions, requesting information, or making recommendations without explicitly naming their source, such as “that the Committee had received a number of credible reports concerning …” Footnote 165 and “according to reliable sources.”Footnote 166 The ratio of express references to NGOs and NHRIs is not high. Whereas CEDAW members tended to give greater weight to NHRI submissions, members of the other two bodies referred to NGO and NHRI submissions equally. Nevertheless, given that the number of NHRIs’ submissions and the total quantity of information contained therein are far less than those of NGOs (see Table 1), the substantial frequency of direct reference to NHRI submissions was higher than that of NGO submissions.

Table 2. Number of treaty body members’ references to external sources

The NHRIs’ opportunities to make oral statements have not affected the frequency of references to NHRI submissions in the CERD and CEDAW. In that sense, their primary effects are symbolic (see Section C-I ). Nevertheless, a qualitative look at the references shows that such opportunities sometimes increased the weight and attention given to NHRI information and views. For example, a National Human Rights Commission representative made a speech in the CEDAW’s consideration of Gambia’s report in its 83rd Session.Footnote 167 Regarding what was said there, Committee member Ms. Reddock asked: “whether, as recommended by the National Human Rights Commission, a study would be carried out into best practices relating to non-discriminatory personal status laws in other predominantly Muslim countries.”Footnote 168

While treaty body members expressly named NHRIs, they refrained from naming NGOs and instead treated them collectively. They have stated, for example, “the concerns expressed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with respect to …”Footnote 169 This implies that while treaty body members believe that the information from and views of NHRIs have credibility and authority, those of NGOs are only worth relying on when they sufficiently converge, and that such a reference should not include specific names. Such practices are consistent with the normative guidance made in Section C-III concerning supplementing treaty bodies’ weak fact-finding capacity.

II. Elaboration of General Comments/Recommendations

Whereas the HRC holds the readings of general comments in public meetings, the CERD and CEDAW draft general recommendations in closed meetings. Therefore, an approach similar to the previous subsection (evaluating the impact of NGO and NHRI submissions by examining the treaty body members’ direct reference) is possible, but only for the HRC.Footnote 170 This article focuses on the summary records of the second readings of General Comments No. 36 (2019) and No. 37 (2020). It examines when and how treaty body members relied on NGOs/NHRIs to (consider to) add, delete, or change terms and phrases and/or the drafting policy.Footnote 171 The second reading is the most appropriate target of analysis because, as Mr. Heyn, the rapporteur for General Comment No. 37, said, “[t]he main purpose of the second reading was to reflect on the draft in the light of [stakeholders’] submissions.”Footnote 172

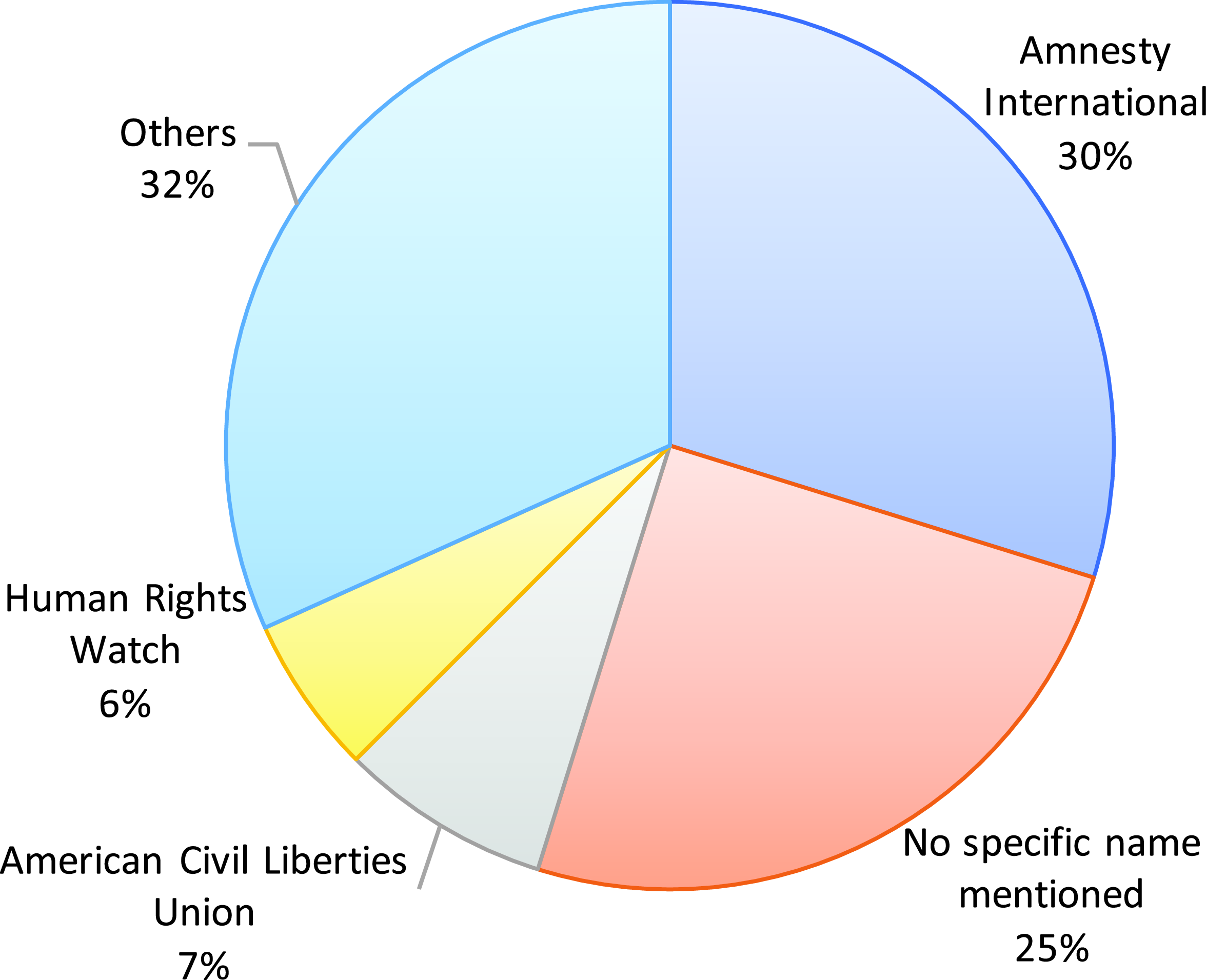

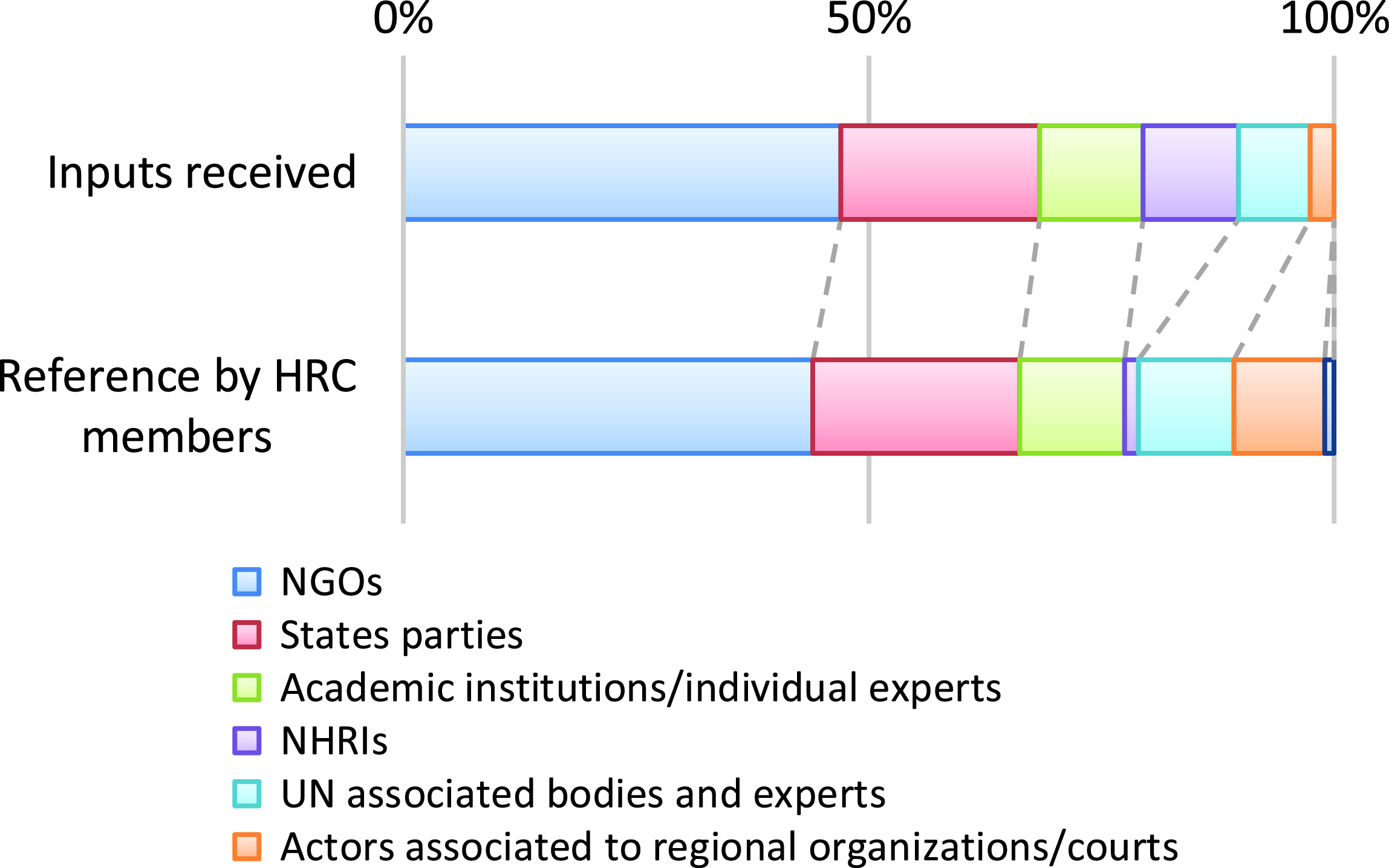

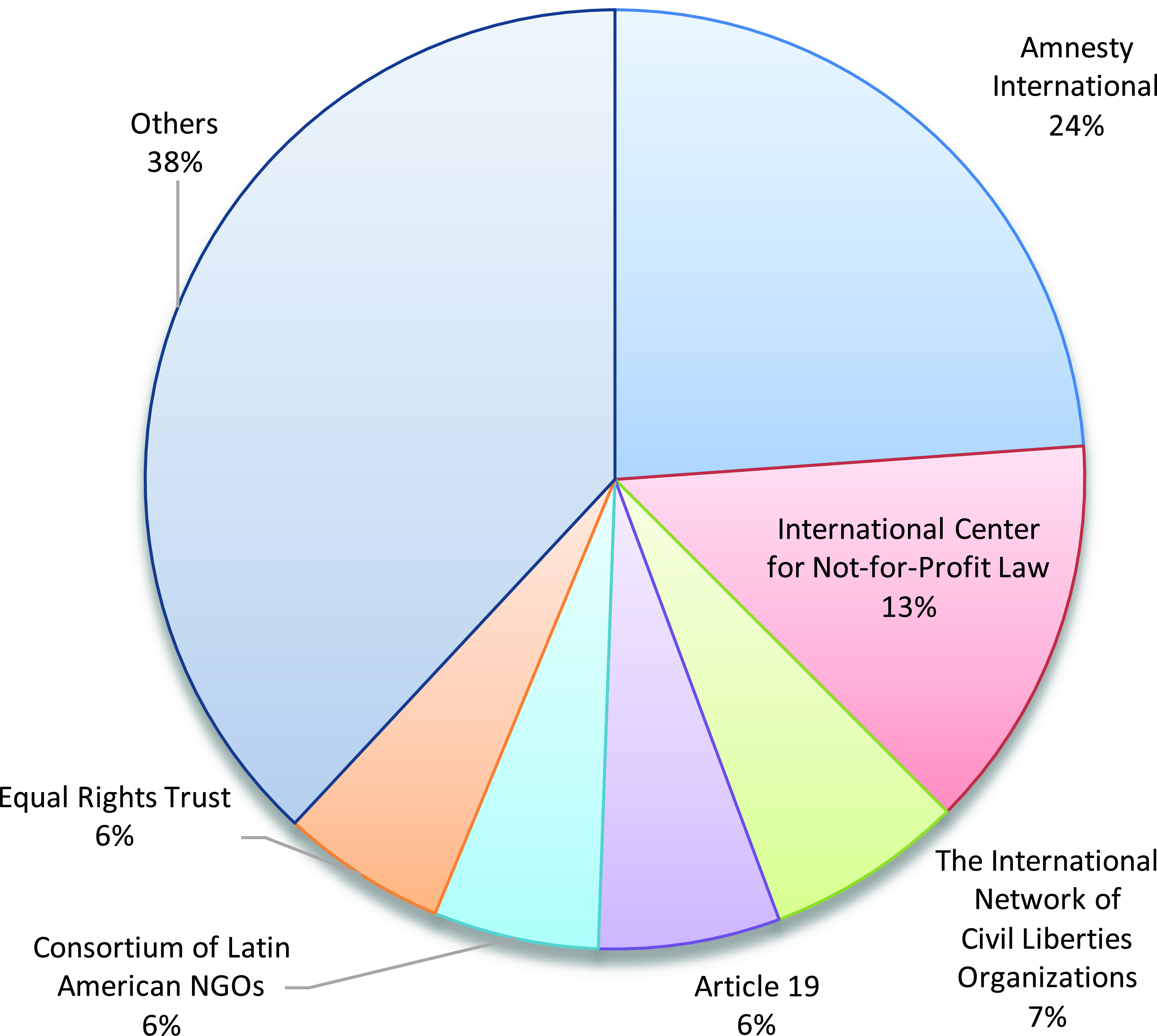

Before the HRC’s second reading of draft General Comment No. 36 on Article 6 (Right to life), 107 reports were received from NGOs, 33 from academic institutions/individual experts, 23 from state parties, 7 from UN-associated bodies and experts, 2 from NHRIs, and 1 from parliamentarians. The second reading was held at the HRC’s 3431st meeting in October 2017 and continued to the 3561st meeting in October 2018.Footnote 173 The comprehensive examination of their summary records showed that out of the 382 references by the HRC members to stakeholder submissions, 248 came from state parties, 104 from NGOs, 15 from academics, 12 from actors associated with the UN and other UN human rights treaty bodies, and 2 from NHRIs. Another actor submitted one report. Figure 1 illustrates this breakdown. The only NHRI submission mentioned was from France’s Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme. Among the NGO submissions, Amnesty International was cited most (31 times), followed by the American Civil Liberties Union (8 times) and Human Rights Watch (6 times) (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. General Comment No. 36: Number of inputs received and references made by treaty body members.

Figure 2. General Comment No. 36: Breakdown of references to NGOs.

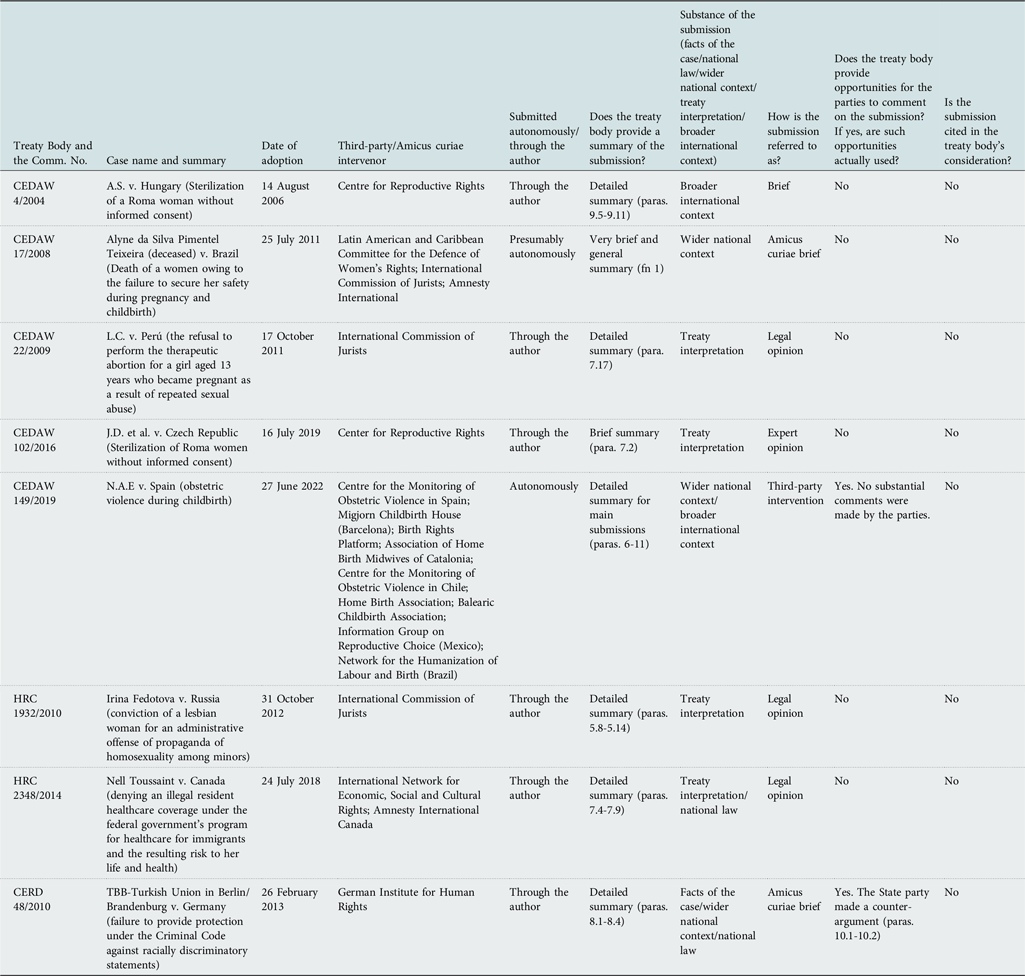

In drafting General Comment No. 37 on Article 21 (Right of peaceful assembly), 55 NGOs, 25 state parties, 13 academic institutions/individual experts, 12 NHRIs, 9 bodies and experts associated with the UN, 3 actors associated with regional organizations and/or courts submitted written comments in advance of the second reading.Footnote 174 The comprehensive examination of the summary records of the second readingFootnote 175 shows that of the 400 direct references to stakeholder submissions by the HRC members, 176 came from NGOs, 89 from state parties, 45 from academic institutions or individual experts, 41 from actors associated with the UN and other UN treaty bodies, 39 from actors associated with regional organizations and/or courts, 6 from NHRIs, and 4 were drawn from other sources. This distribution is illustrated in Figure 3. References to NHRIs include mentions of the Commission on Human Rights of the PhilippinesFootnote 176 and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.Footnote 177 Among the NGOs, Amnesty International was cited most (42 times), followed by the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (24 times), the International Network of Civil Liberties Organizations (12 times), Article 19 (11 times), Consortium of Latin American NGOs (10 times), and the Equal Rights Trust (10 times) (Figure 4).

Figure 3. General Comment No. 37: Number of inputs received and references by treaty body members.

Figure 4. General Comment No. 37: Breakdown of references to NGOs.

As the rapporteur takes the initiative in the discussion by introducing relevant stakeholder submissions and making proposals in the second reading, their approach affects the number of references and their sources.Footnote 178 However, in both second readings examined above, four tendencies were discerned, all of which largely endorsed the normative guidance made in Section C-II from the perspective of promoting deliberations on human rights treaty standards at the international level. First, the rapporteur and other HRC members heavily relied on NGO submissions, especially those with a global reach, such as Amnesty International. Second, when combined with a qualitative analysis, the above statistics show that the rapporteur and other members did not privilege the views of state parties over those of NGOs and other stakeholders but treated them equally. For example, in drafting Paragraph 48 of General Comment No. 37, which concerns the degree to which restrictions on the right of peaceful assembly were justified in the interests of national security, the rapporteur, Mr. Heyns, introduced the contradicting views of Russia and the Consortium of Latin American NGOs, and proposed the wording that “represented [a] middle ground between those two approaches.”Footnote 179 Third, references to NHRIs are low relative to the total number of references and NHRI submissions. The reason for this discrepancy may be that the scope of most of their submissions is limited to their national experience. For example, the NHRI of Cyprus surveyed children’s opinions on the right to peaceful assembly but covered only Cypriot children.Footnote 180 Finally, in contrast to the examination of state reports, where treaty body members have refrained from naming NGOs, HRC members have not hesitated to do so in elaborating general comments.

III. Individual Communications Procedure

Section B-I-3 examined four channels through which NGOs/NHRIs may address treaty bodies in the individual communications procedure. Among the four channels, channel (iv), submitting a brief as a third-party/amicus curiae, most effectively provides the opportunity for NGOs/NHRIs to make unique and independent contributions to the individual communications procedure beyond seeking individual victims’ redress. Thus, only the fourth type is studied.

Table 3 shows that in a limited number of cases, treaty bodies have admitted third-party/amicus curiae briefs from NGOs/NHRIs. The CEDAW has admitted them in five cases and the HRC in two. In all these cases, the submissions were made by international or local NGOs. The CERD has received an amicus curiae brief in only one case from a German NHRI (German Institute of Human Rights, or GIHR). In most cases, briefs have been submitted through the authors. The scarcity of third-party/amicus curiae participation in general and “autonomous” participation (not submitted through one of the parties) in particular can be explained by the fact that the CERD does not make the table of pending cases available to the public and that the CEDAW and HRC publish such tables with very brief descriptions, which only include the name of the state party concerned, the articles involved, and the subject matter in one phrase.Footnote 181

Table 3. List of cases with NGO and NHRI participation

The third-party/amicus curiae submissions addressed one or more of the following aspects: (i) supplementing the facts of the case; (ii) elaborating on the national legal system and jurisprudence;Footnote 182 (iii) explaining a wider national context relevant to the balancing of rights and interests in the case, such as social repercussions caused by the act in question;Footnote 183 (iv) providing legal materials and rationales for treaty interpretation, such as the relevant jurisprudence of other judicial bodiesFootnote 184 and explanations differentiating the case from previous ones;Footnote 185 and (v) explaining the broader international context relevant to the case, such as international medical standards and guidelines.Footnote 186 Items (i) and (ii) correspond to the value of supplementing the treaty bodies’ weak fact-finding capacity (Section C-III ), item (iii) to the value of facilitating “bounded” deliberations at the national level (Section C-I ), and items (iv) and (v) to the value of promoting deliberations on human rights treaty standards at the international level (Section C-II ). As a general tendency, international NGOs have engaged in items (iv) and (v). By contrast, NHRIs and local NGOs were devoted to items (i), (ii), and (iii), which largely reflect their areas of strength (see Section C).

Unlike state reporting procedures and the HRC’s drafting of general comments, where meetings are held in public, individual communications are examined in closed meetings. Thus, to analyze the impact of NGO and NHRI participation on Views and Opinions, this subsection first examines whether their submissions are referred to by the treaty body in their consideration of admissibility and/or merits of a case under the title “Issues and proceedings before the Committee.” As Table 3 shows, in no case did the treaty body expressly refer to NGO and NHRI submissions. Second, it studied whether such submissions were transmitted to the parties, whether they have been allowed to comment on these submissions, and whether they have in fact commented on them. Table 3 shows that in two cases, N.A.E v. Spain (CEDAW, 2022) and TBB-Turkish Union in Berlin/Brandenburg v. Germany (CERD, 2013), the parties were given the opportunity to respond to NGO and NHRI submissions. In the latter case, the state party provided detailed counterarguments against the GIHR’s submissions and stated that “it rejects [GIHR’s] opinions and regards them as wrong and deplorable.”Footnote 187 Thus, although the CERD did not expressly refer to the GIHR’s submissions in its consideration, the GIHR contributed significantly to the examination by eliciting the state party’s detailed rebuttal on the disputed point, thus promoting deliberation. From the normative points of view of facilitating “bounded” national deliberation (Section C-I ) and international deliberation (Section C-II ), opportunities for the parties to comment on third-party or amicus curiae submissions, and the treaty bodies’ readiness to consider such comments along with these submissions, are essential. Treaty bodies are headed in that direction, as newly adopted guidelines on the third-party intervention of the HRC and CEDAW make it clear that the parties to the communication are entitled to submit written observations and comments and that the Committees may use third-party submissions in their deliberations and Views.Footnote 188

E. Conclusion

This study dissects stakeholder participation in treaty body activities, whose benefits and problems have only been discussed in a generalized or fragmented manner in the literature. It systematizes the multifaceted values of stakeholder participation in treaty body activities in an original manner. In addition, it normatively evaluates and empirically analyzes the relative weights of those values for the two main stakeholders, NGOs and NHRIs, and for different activities, namely state reporting and individual communications procedures, and the elaboration of general comments/recommendations.

This study offers concrete normative guidance for treaty bodies and critical evaluations of their current practice, which the literature has generally lacked. These findings can be used to legitimatize the current practice to the extent that it is in line with this article’s normative guidance, and to further develop treaty body procedures and practices on stakeholder participation, which are currently being consolidated. This article also shows that NHRIs, especially those with A-status, are normatively expected to and, in fact, do play unique roles distinct from NGOs when they participate in treaty body activities. A-status NHRIs have a significant advantage in supplementing treaty bodies’ weak fact-finding capabilities in a trustworthy manner and connecting the formal and informal public spheres in facilitating “bounded” national deliberations. They can contribute to international deliberations on human rights treaty standards if they act collectively. This finding can be used to persuade states without A-status NHRI to create one or strengthen existing ones.

Finally, a few tasks remain for future research. First, this study focused on the value and effect of stakeholder participation in the form of provision of inputs, thus excluding the implementation of treaty bodies’ recommendations from its scope. However, both aspects are closely interrelated in reality. Many previous studies have demonstrated that domestic and transnational mobilization is crucial for implementing human rights treaties and treaty body recommendations and that NGOs and NHRIs play central roles in such mobilization by invoking treaty bodies’ concluding observations, general comments/recommendations, and Views/Opinions.Footnote 189 Moreover, other studies have implied a correlation between NGOs’ participation in treaty body activities and their leading roles in mobilization.Footnote 190 Stakeholder participation by NGOs and NHRIs may create an opportunity for treaty bodies to inform, educate, and empower them and foster an effective partnership toward domestic and transnational mobilization. Thus, future studies should integrate the implementation aspect into the theoretical frameworks provided in this study. Second, whereas this study empirically examined the treaty bodies’ practice on engagement with NGO and NHRI participation under an original normative framework, it has left unexplored the sociological factors that may have affected the practice, such as the relationship between individual treaty body members’ professional trajectories and their openness to engagement.Footnote 191 Future studies to address such sociological factors to draw policy implications, for example, concerning the composition of treaty bodies, would be interesting and valuable. Finally, the increase in stakeholder participation and the accompanying normative and practical challenges are global phenomena.Footnote 192 Therefore, future research should examine the applicability and limits of this study’s normative frameworks and findings, not only to other UN human rights treaty bodies and other treaty body activities such as the inquiry procedure, but also to regional human rights courts and judicial and non-judicial mechanisms in other fields.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Hiroko Akizuki (member of the CEDAW since 2019) and Professor Keiko Ko (member of the CERD 2018-2021) for helping me develop a concrete understanding of the actual practice of UN human rights treaty bodies. All errors remain my own.

Competing of Interests

None.

Funding details

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 22K13291, 23H00035, and 23H00037, and Sumisei Woman Researcher Encouragement Prize.