A. Introduction

Why do judges dissent? Traditional answers focus on the opportunity dissent provides for judges to express disagreement with both the legal merits and the policies resulting from the court’s decision. Dissents can serve as a useful outlet valve, allowing judges to “satisfy [their] conscience” on important matters of jurisprudence.Footnote 1 Alternatively, dissents can speak to “the intelligence of a future day,”Footnote 2 when a new understanding of the law will be recognized. In so doing, dissent also performs a vital role in the judicial system—that of “contribut[ing] to the continuing development of the law.”Footnote 3

In democratic society, judicial dissent can also help courts express the values of deliberative democracy, engaging in and contributing to the larger public discussions over constitutional and legal outcomes.Footnote 4 Yet, dissenting opinions might also contribute to confusion and uncertainty in the law, and could perhaps lead to the de-legitimization of the court’s outcome. It is largely for reasons of certainty and legitimacy that most continental European states traditionally shunned the practice of dissent, though today this prohibition no longer exists on most European constitutional courts.Footnote 5 Ultimately, however, the normative value of dissent—particularly in democratic society—could hinge on how dissent is used by the judges who hold that power.

This Article examines changes in dissent patterns that occurred during a period of intense constitutional and political change in Poland—a time of ongoing political drama—in which the Polish Constitutional Tribunal was thrust into a central role. An analysis of these dissents shows Tribunal judges rarely used them to express the traditional differences of opinion on law or policy. Instead, judges on the Tribunal increasingly used dissents as a way to broadcast allegations of legal and procedural violations that have occurred within the court’s operation itself. More troublingly, some judges also used their dissents to advance distinctly political narratives and overtly attempt to de-legitimize the court’s announced decisions.Footnote 6

Thus, we can see in Poland the development of dissent as a tool to express the deep political cleavage that took root within the Tribunal after the 2015 constitutional crisis began—a cleavage that mirrored the disruptive political practices of the Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość “PIS”). The Tribunal’s very public arguments over its internal workings and processes, including debates on the very composition of the Court and on which judges could properly decide cases, represents a notable shift in the use of the separate opinion that is worth careful consideration. This shift has occurred during an extraordinary time of political volatility in Poland. Yet, as more and more established democracies begin to experience this same volatility, the trends seen here could be repeated in other countries.

Many aspects of the Polish constitutional crisis have been told in both academic works and the popular media.Footnote 7 What is less well known, but just as important, is how the judges on the Tribunal have responded to these political pressures in their own written work. As Katalin Kelemen has noted, dissenting opinions provide legal researchers a unique tool with which to examine the internal debates among judges—debates that otherwise are hidden from public view.Footnote 8 An examination of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal dissents show that constitutional judges may not be immune to participating in the larger social and constitutional battles within society. In fact, these dissent patterns suggest that, in a more fragmented and polarized era of politics, judges can use dissenting opinions to broadcast distinctly political messages.

This Article proceeds as follows: The first section discusses traditional theories from both law and political science that attempt to explain why and when judges write dissenting opinions; the next section describes the political environment in Poland since PiS entered government in November 2015 before moving to a detailed discussion of Constitutional Tribunal dissents since this change in power; the final section analyzes these trends and concludes with some thoughts on how these changing dissents fit into the normative value of judicial dissent.

B. Traditional Theories: Why Dissent?

A dissenting opinion reflects a decision by at least one member of a collegial judicial decision-making body to make public an underlying disagreement within the group.Footnote 9 Where it is offered, the decision to file a dissenting opinion has been viewed by many legal scholars and practitioners as an opportunity to advance several important interests. First, the dissent can provide both legal actors and the general public with a different narrative of law and of jurisprudence that can be used to guide future changes in the law. Justice William Brennan, for example, described dissents as a needed tool to show the public that the majority has adopted an incorrect interpretation of the law and “point” the community “toward a different path.”Footnote 10 As a corollary, Brennan’s conception also finds judicial dissent to be beneficial to the democratic legitimacy of courts, an idea that Brennan’s ideological opposite, Justice Antonin Scalia, also noted a decade later in his own writings on dissent.Footnote 11

A second possible benefit arising from judicial dissent: At least at the high court level, current theory and evidence also points to the use of dissents as a way to express differences with the policy endorsed or created by the court majority.Footnote 12 This is perhaps most true in the decisions of the United States Supreme Court, where dissenters are regularly grouped into liberal and conservative blocs,Footnote 13 though policy difference also helps explain dissent patterns in state courts, lower federal courts, and many European constitutional courts.Footnote 14

Relatedly, judges can also use dissenting and separate opinions strategically to invite further review of specific issues and signal a willingness to change doctrine.Footnote 15 Justice Samuel Alito’s recent concurrence in Gundy v. United States, a non-delegation doctrine case, is a primary example of such behavior.Footnote 16 Writing separately from the majority opinion, he pointedly noted that, “if a majority of this Court were willing to reconsider the [non-delegation] approach we have taken for the past 84 years, I would support that effort.”Footnote 17 In 2007, Alito also appeared to invite litigants to challenge existing campaign finance laws by noting in a special concurrence to FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life that if those campaign finance laws chill political speech, “we will presumably be asked in a future case to reconsider” the constitutionality of campaign finance laws.Footnote 18 One year later the Court accepted a case brought by Citizens United which eventually overturned that very campaign finance law.

Despite the potential individual benefits, the decision to dissent is far from a costless exercise for the judges on a collegial court. As Epstein, Landes, and Posner note, there is a short-term cost in terms of the time spent writing a dissenting opinion.Footnote 19 Over the longer term, judges also must consider the potential for friction between the opinion writer and other members of the court—a particularly important consideration on collegial courts. Examining the appellate courts in the United States, Bowie, Songer, and Szmer find that the need to maintain cordial relationships results in judges withholding dissenting opinions in many cases.Footnote 20 Similar pressures also appear to be at work on many European constitutional courts. Former German Constitutional Court judge Dieter Grimm has described the extreme reticence many of his colleagues felt toward dissent.Footnote 21 Several current and former constitutional court judges in Poland have described this reticence as a product of the long deliberation that occurs in the decision-making process on the constitutional courts.Footnote 22 Thus, dissent in the European legal landscape is often portrayed as an “exceptional circumstance” that occurs when a judge feels compelled by conscience to act.Footnote 23

The decision to dissent creates another potential cost. That cost is to judicial reputation and the legitimacy of the court as a whole.Footnote 24 If the content of a dissenting opinion increases the perception that judges place personal interests, notably their own policy interests, above the collective good, then the reputation of judges as neutral and impartial problem solvers declines. This concern is more than abstract. Research by Naurin and Stiansen has found that the presence of dissenting opinions can reduce the probability that other actors will comply with court decisions.Footnote 25 This danger of politicization has been noted as a primary reason not to have dissent, particularly in courts where judges serve fixed terms in office.Footnote 26 In fact, some have argued that the inability of many European constitutional judges to create separate opinions has led to a notable “lack of politicization” within those courts.Footnote 27 Even in the United States, where dissent abounds, experimental research has found that public reactions to Supreme Court opinions are generally more positive if the decision is unanimous.Footnote 28

The importance of reputation and legitimacy are all the more important for constitutional courts due to the uniquely political legal environment in which these courts operate.Footnote 29 Nuno Garoupa and Tom Ginsburg argue that constitutional court judges really have two, sometimes competing audiences. The first is the political audience, which includes the judge’s appointing party and the politicians who may offer them jobs post-court. The second is the judicial audience, which is comprised both of other judges and the larger legal community.Footnote 30 The comparative pull of these two audiences could have an effect on the ability of judges to reach consensus. Garoupa and Ginsburg predict that constitutional court decisions and voting outcomes will be more or less fragmented based on the incentives provided to the justices on the court. Notably, judges seeking to enhance their reputation with a specific political actor will try to signal that loyalty, notably by issuing dissents when they are in the minority on the court.Footnote 31 Yet, dissent creation in this type of political environment can lower the public’s confidence in the court as a whole.

At the same time, many other scholars and jurists view the dissent as a sign of openness and deliberative transparency that should have salutary effects on the court’s democratic legitimacy and authority.Footnote 32 Publishing dissent opens the doors of the deliberative process, uncovering debated points and allowing the public to understand the competing arguments in the case. Dissent can also express the doubts that the court has over the direction of the law, and in doing so, can show the public the limits of the court’s decision in a way that unanimous or consensus decisions cannot. The give-and-take process in dissent writing can also sharpen the court’s final arguments and reasoning, resulting in qualitatively better legal outcomes.Footnote 33

In describing the benefits of writing separately, Justice Antonin Scalia noted that the democratic authority of the courts is enhanced by the ability to dissent. Dissent shows the public that judicial decisions are the product of independent and reasoned debate on the merits. At the same time, they also show that judges “do not simply ‘go along’ for some supposed ‘good of the institution.’”Footnote 34 Similarly, dissents can help ensure the transparency of the decision-making process, expressing reasons that can be evaluated by the public, which should similarly enhance the democratic legitimacy of court decision-making. In effect, the dissenting opinion allows judges to become part of the larger public debate on matters of law and of the policies established by those laws.

Yet, there could be a critical limitation to the democracy-enhancing aspects of dissent: All sides in the marketplace of political competition must accept the constitutional court’s role in guarding fundamental rights and liberties.Footnote 35 If actors who refuse to accept the current constitutional bargain are able to appoint judges to the court, dissenting opinions from those judges could begin to be seen not as reasoned and principled differences on law’s reach, but simply as part of a less principled political battlefield. This democracy-enhancing limitation has critical importance today, as populist parties like PiS in Poland generally are defined by their desire to fundamentally change and restructure the current constitutional order through the political process.Footnote 36 In other words, they do not accept the current constitutional bargain.

Ultimately, these explanations and theories on the merits of dissenting opinions are integral to evaluating the opinion writing behavior of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal after the December 2015 constitutional crisis. During this period, the court witnessed a dramatic uptick in the overall percentage of dissents attached to cases in their abstract review docket, as well as very large numbers of dissents seen in their concrete review cases.Footnote 37 The content of those dissents shows that many judges began using these opinions in a way not seen previously. Specifically, many judges have used the dissent not as a way to express disagreements on the outcomes of the case, but rather, as a platform to express fundamental disagreements on the court’s very composition, as well as issues with larger court procedures and operating practices. At the same time, many of the dissents by the PiS appointees also appear explicitly designed to advance a political narrative—the narrative of the political party that appointed them to the bench. Both of these trends are troubling for the legitimacy of the court as a whole.Footnote 38

C. Poland’s Constitutional Crisis

Poland’s current constitutional conflict began in early October 2015, just before the country’s parliamentary elections, when the center-right Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska “PO”) government appointed five judges to fill soon-to-be empty seats on the Constitutional Tribunal—including two seats that were not scheduled to be empty until after the next parliamentary session had begun. The PO had governed Poland as the dominant coalition partner since 2007, but its popularity began to wane in late 2014. Ultimately, it lost the October 2015 election decisively to the populist national conservative Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość “PiS”), which gained enough seats to form the first single-party majority government in post-1989 democratic Poland.

Though PiS won the election by campaigning to lower retirement ages, increase monthly subsidies for parents, and limit Poland’s participation in an EU refugee resettlement program, the party dramatically shifted the focus of its legislative agenda just weeks after entering government. Instead of acting on those economic measures, PiS deputies initiated legislation in late November 2015 to annul the appointment of the five judges appointed in October by PO. Concurrently, PiS pushed through the midnight confirmation of five new judges to replace those appointees terminated just days earlier.

All of these actions were challenged on constitutional grounds, and the various claims ultimately ended up on the Constitutional Tribunal’s docket. One week after PiS’s midnight confirmations, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled that two of PO’s five October appointees could not be seated, as they were elected to fill seats not yet open.Footnote 39 At the same time, the Tribunal determined that the remaining three October nominees must be given the oath of office and seated, as they were validly elected by parliament to replace judges whose terms expired on November 6, 2015—before the new parliamentary term began, and before PiS took control of parliament. In so ruling, the court also determined that three of the five PiS “midnight” judges could not be seated, as there were three judges already validly elected to fill those spots. However, both President Andrzej Duda, who had run under the PiS banner, and the new PiS parliament refused to accept the court’s ruling. They insisted all five of their slate must be installed.Footnote 40 On the opposite side, Tribunal President Andrzej Rzepliński would agree that two PiS judges could enter the court but refused to seat all five.

As condemnation of these first actions began pouring in,Footnote 41 PiS deputies initiated a new round of laws in December 2015 designed to dismantle the independence of the Constitutional Tribunal, the public news media, and the civil service. Among other changes, legislation on December 22, 2015 altered the Tribunal’s governing law to require a supermajority of two-thirds to overturn any legislative act and mandated a new minimum quorum of thirteen judges to hear most cases, which would force the Tribunal to accept all of PiS’s judges before it could continue hearing cases. In less than two months, Poland—long considered a model of post-communist democratic and economic development—suddenly faced a pair of constitutional crises seemingly designed to paralyze, even destroy, the country’s popular Constitutional Tribunal and weaken important checks on government power.

Though the timing of PiS’s confrontation with the courts was surprising, the rationale justifying it was familiar to followers of Polish politics. Before and after the midnight judges vote, Jarosław Kaczyński, the party’s founder and long-time chairman, stated that the powers of the Constitutional Tribunal must be reduced because Tribunal President Rzepliński was “Civic Platform’s guy,” and suggested the court was secretly working with PO to advance “a small but influential group in society” that sought to undermine Polish democracy.Footnote 42 Those in society who opposed PiS’s actions were dismissed as “Poles of the worst sort,” continuing their “tradition of national treason.”Footnote 43 In fact, Kaczyński had been making similar statements about the Constitutional Tribunal since 2005, when PiS first entered government. After the Tribunal ruled against several PiS initiatives in 2005 and 2006, Kaczyński—then Prime Minister—charged that judges on the Tribunal were “not guided by Poland’s national interests,” but rather a shadowy elite at the top of society.Footnote 44 Later, Kaczyński stated he would need to change the makeup of the court, as it was “evident in their verdicts” that many “individuals in the Constitutional Tribunal . . . are associated with” his political enemies.Footnote 45 Now back in charge of government for the first time since 2007, PiS immediately set out to fundamentally change the court.Footnote 46

The tumult within the Tribunal did not end with the December judges controversy. With the three contested seats not yet resolved, in March 2016 a twelve-member Tribunal struck down key elements of PiS’s December law that was intended to limit the Tribunal’s jurisdiction and scope of action.Footnote 47 However, on Prime Minister Beate Szydło’s orders, the government printing office did not print the Tribunal’s decision in the Journal of Laws (Monitor Polski), thus rendering it an unofficial decision, at least in the eyes of PiS and many of its supporters. PiS then passed a new law governing the Constitutional Tribunal in July 2016, which the Tribunal again struck down. All the while, President Rzeplińksi continued until the end of his term of office in December 2016 not to allow the remaining three PiS judges appointed in December to join the court as full members. Conversely, President Duda refused to follow the Tribunal’s decision and give the oath of office to the three appointees confirmed by PO in October 2015 and ratified by the Tribunal in December.

When Rzeplińksi’s term ended in December 2016, Julia Przyłȩbska, one of the first two PiS appointees to enter the court, was named by Duda to be the new Tribunal President. The PiS-appointed prosecutor general then asked the Tribunal to suspend three judges appointed in 2010 by PO—a request Przyłȩbska agreed to. Judges Marek Zubik, Piotr Tuleja, and Stanisław Rymar were all excluded from participating in the Tribunal’s voting and deliberations for most of 2017. Przyłȩbska also ordered the Tribunal’s long-standing Vice President, Stanisław Biernat, to use all of his unused holiday leave time, which effectively suspended him from the Tribunal’s work for the duration of his term in office.Footnote 48 With four of the group that came to be known as the “old” Tribunal judges now suspended, and the prospect of several additional retirements in the 2017 calendar year, PiS was now ascendant on the court.

D. Dissenting Practices in the Post-2015 Constitutional Tribunal

In this context of ongoing political turmoil, both outside and inside the court chambers, a major shift in the overall quantity of dissent and the tenor of dissent began to take hold on the Constitutional Tribunal. As an initial matter, some context on dissent patterns is in order. On average, European constitutional courts have dissent rates that are much lower than the U.S. Supreme Court. One study of five constitutional courts found dissenting opinions filed in approximately twenty percent of cases, with Polish Constitutional Tribunal very close to that average as approximately nineteen percent of abstract review cases decided by the Tribunal since the early 2000s had at least one dissenting opinion.Footnote 49

However, beginning in 2016 the annual dissent rate on the Tribunal rose precipitously. (See Figure 1.) In 2016, fifty-nine percent of abstract review cases—ten of seventeen decisions—saw a dissent filed, with the three PiS-appointed judgesFootnote 50 responsible for nineteen of the twenty dissenting opinions filed in those ten cases. With new PiS leadership on the court in 2017, the high rate of dissents continued: Fifty percent of the abstract review decisions—six of the twelve decisions—had a dissenting opinion attached, with the vast majority of the ten total dissenting opinions in those 2017 cases filed by the “old,” pre-2015 judges. Though the sheer number of dissents filed is remarkable, even more striking has been the tone and the content of the dissenting opinions since the December 2015 constitutional crisis began.

Figure 1. Abstract Review Decisions from Polish Constitutional Tribunal, 2003-2018

At first, the increase in dissent might be confused with what many political scientists refer to as “attitudinal” judgingFootnote 51—that PiS-appointed judges dissent from the rulings because they disagree with the policy the non-PiS-appointed judges adopted, and vice-versa. A closer examination of the text of these dissents reveals a picture that is both similar to, and yet altogether different from, the attitudinal model of judging. Rather than focusing on law or policy, nearly all dissents by the new PiS judges and the older judges have been used to publicly air allegations of legal and procedural violations each side has accused the other of perpetrating while in control of the court. Also notable is that many of the dissents explicitly attempt to delegitimize the majority’s decision. Where did this change originate? The story begins early in 2016 with the Tribunal’s landmark decision overruling PiS’s first Constitutional Tribunal law, and the response from the new PiS appointees.

I. PiS’s Constitutional Tribunal Amendments Are Overturned: Decision K 47/15

PiS’s initial move to rein in the Constitutional Tribunal concluded on March 9, 2016 at the Tribunal’s main hearing room, with ten of the court’s twelve judges voting to overturn major portions of the December Constitutional Tribunal law, including sections of the law that required a quorum of thirteen judges to handle most cases and the section that required a two-thirds supermajority to overturn legislation.Footnote 52 The majority’s ruling focused on issues of judicial independence—notably, that major sections of the law would reduce the independent action of the Tribunal in contradiction to the terms of the Polish Constitution. Yet, this decision also included furious dissents by Julia Przyłȩbska and Piotr Pszczόłkowski, the two PiS-appointed judges sitting on the bench. Both filed dissenting opinions that are quite long and substantive—Przyłȩbska’s dissent was 2,434 words while Pszczόłkowski’s was 4,203 words.

Judge Przyłȩbska’s dissent focused on several arguments that had been highlighted by PiS in the run-up to the court hearing.Footnote 53 At the outset, she argued that the Tribunal was required to follow the procedures spelled out in PiS’s amended Constitutional Tribunal Law of December 22, 2015 before reviewing the law’s constitutionality. Specifically, she noted that the law under review required at least thirteen judges—of a possible fifteen—to be present on the bench. In this case, twelve judges were present on the bench, which she believed nullified the lawfulness of the Tribunal’s final ruling. In fact, the Tribunal’s composition was one of the political subtexts in the case. PiS introduced the thirteen-judge quorum into the December 22, 2015 law as a way to force their three remaining December nominees onto the court.

Following PiS’s public arguments,Footnote 54 Przyłȩbska’s dissent noted that it would be possible for the new quorum to be obtained if the Tribunal’s president would accept the three contested PiS appointees from December: Lech Morawski, Mariusz Muszyński, and Henryk Cioch. To do that, however, the Tribunal would have had to overturn its own decision from December 3, 2015, in which the court determined that three of the five PO October appointees were appointed in a constitutional manner and thus should be permitted to take office.Footnote 55 Przyłȩbska also objected to the timeframe of the proceedings: Article 87(2) of PiS’s December law required that public hearings generally cannot take place with less than three months’ notice to the parties. She argued the Tribunal similarly failed to follow this aspect of the law before reviewing it.Footnote 56 Again, this argument relies on the idea that the Tribunal should be obliged to apply laws regulating itself before reviewing them for constitutionality, something the court majority rejected based on past practices and precedent.

Judge Pszczόłkowski’s dissent also focused on the exclusion of the three contested PiS judges, but did so from a slightly different perspective. He emphasized more directly Tribunal President Andrzej Rzepliński’s decision not to seat the three contested PiS judges. Pszczόłkowski noted that, having been approved by parliament and given the oath of office by the Polish President, it should not be up to the Tribunal President to then determine whether or not those judges are seated to hear cases. Instead, Pszczόłkowski explained, “[a] judge on the Constitutional Tribunal is a person elected by the Sejm” and sworn in by the President—a simple set of circumstances that meant the Tribunal President was “without any legal basis” to exclude the three contested PiS judges.Footnote 57 He also noted that, after President Duda gave the three contested judges the oath of office, Rzepliński assigned those judges rooms in the Tribunal building and allowed them to receive remuneration, but did not give offices or salaries to the PO judges elected in October. To Pszczόłkowski, this showed “without a doubt” that factually and legally the PiS judges should have participated in this case.Footnote 58

This last conclusion is debatable, legally and factually. In reality President Duda refused to give any of the five PO judges the oath of office after their election by parliament, an underhanded move that was designed to prevent the PO judges being able to take office as judges. That is the most obvious reason why they did not receive salaries or offices in the Tribunal building. If Rzepliński had allowed them in as judges without first receiving the mandated oath of office, this action would certainly have been criticized as an unconstitutional usurpation of power by the Tribunal President.

Like Przyłȩbska, Pszczόłkowski’s dissent also questioned the decision to review PiS’s amended Constitutional Tribunal Act without first adopting the changes to the court’s composition, leadership, and procedures, noting, “judges of the Tribunal. . . cannot by themselves ignore such provisions, even if they consider them to be ‘obviously’ unconstitutional.”Footnote 59

The arguments in these dissents ultimately had large implications for the future position of the Tribunal. After the verdict was announced, Prime Minister Beate Szydło ordered the government printing press not to publish the decision in the Monitor Polski. Mirroring the dissenters arguments, Szydło claimed this step was necessary because, by not applying PiS’s 2015 amendments before weighing their constitutionality, the court’s ruling itself violated the law.Footnote 60 President Duda similarly picked up on the dissenter’s arguments when making his own remarks supporting the Prime Minister’s position not to publish the verdict.Footnote 61 Not publishing the ruling has serious consequences: The Polish Constitution states that each judgment takes effect “from the day of its publication.”Footnote 62 Failure to publish arguably meant the ruling was not truly binding.Footnote 63

II. Recitation of Grievance: The Post-March 2016 Dissents

The dissenting opinions in the March case could be viewed, at least, in part as political documents, in that the PiS appointees largely echoed arguments made publicly by their appointing party before the hearing.Footnote 64 After the publication of these initial dissents, however, an even more unusual pattern developed. Subsequent Tribunal decisions continued to see the PiS appointees file dissenting opinions. Yet, rather than dissent over the substance of the court’s decision—such as the interpretive methods used by the court majority or the policy decided in the final decision—these latter dissents continued to focus on the Tribunal’s March decision overturning parts of PiS’s court curbing law and the continued inability of PiS to see all five December appointees enter the Tribunal. In short, the dissents became rote recitations of grievance over the composition of the court and the decision to overturn PiS’s court bill—and not the substance of the court’s final decision in the case at hand.

Two cases the Tribunal decided on May 25, 2016 illustrate this trend well.Footnote 65 By May, a third PiS appointee, Zbigniew Jędrzejewski, had entered the court to replace the retiring Judge Mirosław Granat. The three PiS appointees filed dissenting opinions in both cases. Przyłębska’s dissents in these two cases were much shorter than her March dissent, an identical 296 words that focused on two main points.

First, she reiterated her view that the composition of the court was incorrect. Specifically, she noted that the Tribunal should have adjudicated this case with a “full panel of judges of the Tribunal, i.e. with the participation of at least thirteen judges,”Footnote 66 which would include the three contested PiS appointees. Why must the full composition include at least thirteen judges? After all, the December 2015 law that required a thirteen judge quorum had been ruled unconstitutional in March. The answer to this question is integrally tied to Przyłębska’s second argument.

Her second point, and the main thrust of the dissenting opinions, focused on the implications of the government’s decision not to publish the Tribunal’s March opinion overturning PiS’s courts law. Not publishing the Tribunal’s decision meant that the outcome never went into force. Thus, Przyłębska argued, all current and future cases “are still regulated by” the December 2015 law, which, she argued, “has not lost its binding force”Footnote 67 despite being overturned by the court.

Pszczόłkowski’s two dissents were now slimmed to 462 nearly identical words, though they still focused on the same subjects touched on in his March dissent. Specifically, he noted the majority opinion improperly failed to apply the procedures in PiS’s December law, and the Tribunal should have seated the three contested PiS appointees as full judges.Footnote 68 Like Przyłębska, he also noted specifically that the government’s decision not to publish case K 47/15 meant that the law overturned in the case—PiS’s December court law—was “still in force and should be applied”Footnote 69 in this and all future cases. Judge Jędrzejewski filed the third set of dissents, which stated in very brief terms that he agreed with Przyłębska’s dissents.

Subsequently, the trio filed six additional dissents between June and July 2016. Many were simply carbon copies of their earlier May dissents. Przyłębska’s next two dissents in cases decided in June and July, all repeat, basically verbatim, the same message: Case K 47/15 has no binding force because the government never published the verdict, and the Tribunal leadership should allow all PiS nominees to enter the court.Footnote 70 For example, in her July 12, 2016 dissent in case K 28/15, Przyłębska again noted that “the panel in this case is inconsistent with the . . . [Constitutional Tribunal] Act of 22 December 2015,” a law that she claimed “has not lost its binding force”Footnote 71 and that should have been applied when creating the judicial panel to decide the case. This message was repeated verbatim on July 19, 2016 when she again argued that “the panel in this case is inconsistent with the. . . [Constitutional Tribunal] Act of 22 December 2015,” which “has not lost its binding force.”Footnote 72 Jędrzejewski’s two subsequent dissents also were identical, briefly stating his belief that the court majority erroneously failed to follow PiS’s overturned December law regulating the Constitutional Tribunal when creating the panel.Footnote 73

Pszczόłkowski’s next two dissentsFootnote 74 also were largely identical in wording and substance, repeating his previous narratives that all PiS appointees should, “without a doubt,” enter the Tribunal as full judges,Footnote 75 and that case K 47/15 has no binding force. Citing the academic works of several current and former Tribunal judges and clerks, Pszczόłkowski noted that unlike the court majority he did “not share the view that the mere announcement of the Constitutional Tribunal’s judgment in case K 47/15 in the courtroom makes it possible for the Tribunal not to apply” the December 2015 law going forward if that judgment was not published in the official register.Footnote 76 His dissents are more substantive and expository than his colleagues’ writings: Both opinions are over 2,300 words in length. At the same time, they are largely carbon copies of one another, with identical paragraphs and citations to authority.Footnote 77

Examining the content of these dissents, it is striking how discordant they are with the tenor of the written decisions by the majority, all of which seek to explain and answer a specific constitutional question. The cases in which all three of the PiS appointees dissented concerned property rights and the rights of incapacitated people; a third case in which Przyłębska dissented focused on the rights of prisoners. Yet, none of the dissents written by the PiS appointees really engage with either the facts of these cases or the law in any real way. Instead, they recite old grievances from previous cases. Ultimately, none of the texts fulfill the primary purpose of the dissenting opinion, which is to explain why the majority’s factual and legal conclusions are incorrect. Additionally, none seem designed to enhance the neutral or principled character of judicial decision-making. Using Garoupa and Ginsburg’s framework, the substance of all of these dissents appears intended for the judge’s political audience—the appointing party that elected them to office, and that party’s supporters.Footnote 78

In July 2016, the PiS-led parliament passed a wholly new Constitutional Tribunal Act. The purpose of the law again was to rein in the Tribunal’s scope of action, with one key provision mandating that the court gain the approval of the Prime Minister before publishing any ruling, and another giving the Prosecutor General—the government’s attorney—the ability to dismiss any case by not appearing at the hearing.Footnote 79 The new law also allowed any ruling to be delayed by six months if four judges agreed to do so. The law was immediately referred to the Tribunal by other members of parliament and the Polish Ombudsman, and in early August the Tribunal struck down major portions of the new Tribunal law.Footnote 80

Again, Przyłębska, Pszczόłkowski, and Jędrzejewski filed dissents. Similar to the March decision in case K 47/15, all three dissents claimed that the Tribunal should have applied the procedures contained in the new Constitutional Tribunal Act before ruling on the law.Footnote 81 In fact, following the terms of the new law would have major strategic implications for the court: Because the new law required all cases currently filed at the Tribunal to be refiled and decided in the order in which they were received there would be no more fast-tracking of important cases. If followed, this rule would have significantly delayed the judges from deciding the July Tribunal law. Jędrzejewski’s dissent also levied a more personal charge: President Rzepliński should not have participated in the case, as he had ceased acting as an impartial judge.Footnote 82 As with the Tribunal’s March ruling, the government also ordered that the August ruling not be published in the Monitor Polski, thus potentially depriving it of legal force, as well.

Przyłębska filed two additional dissents after this August ruling: One in a labor law case and the other in a case about driving fines.Footnote 83 Both dissents are near carbon copies of one another, with neither focusing on the merits or substance of the case being decided. Mirroring earlier writings, both dissents argue that her fellow judges should have applied the Constitutional Tribunal Act that was overturned in August because the government again took the dubious step of not printing the court’s final decision in that August case. Specifically, she noted at the conclusion of both dissents that the overturned Constitutional Tribunal Act was “still part of the applicable legal order” that everyone, including the Tribunal, was obliged to follow.Footnote 84 Ultimately, both of her final dissents continue the call to disregard the Tribunal’s final rulings; instead, they argue for the legal community—and the public—to uphold and apply laws previously overturned by the Tribunal.

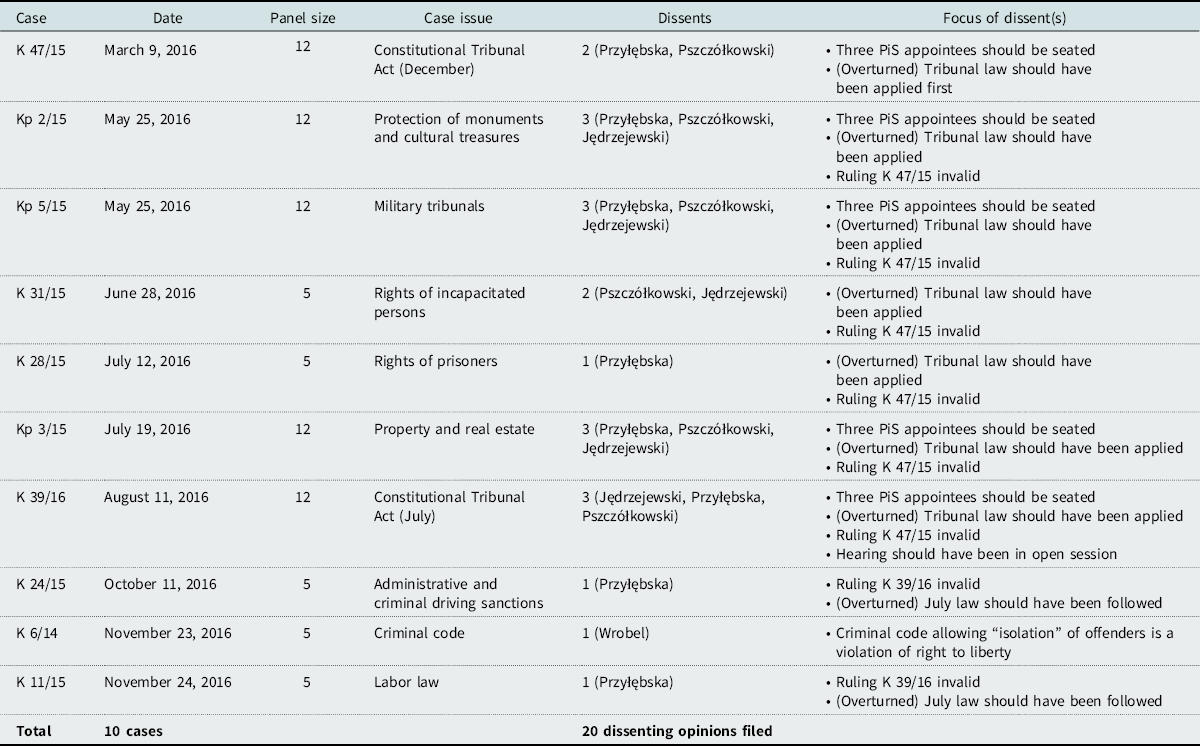

Overall, ten of the seventeen abstract review cases decided in 2016 included a dissenting opinion, a dramatic increase over previous years. Those ten cases had a total of twenty individual dissents filed, with nineteen of those twenty dissents written by the three new PiS judges on the Tribunal. (See Table 1.) Apart from the sheer number of dissents, it is the tenor of these dissents that represents a truly remarkable change from the typical separate opinion. Garoupa and Ginsburg earlier theorized that the influence of the constitutional court’s political audience could lead to higher fragmentation and higher dissent in the court’s final outcome. That appears to be the case here: Most dissents in 2016 appear to be pitched directly toward a political audience. Though nineteen dissents were filed, only dissents in two cases—those from the March and August court curbing laws—engage with the facts and issues the judges are called on to resolve in the specific case. The remaining dissents are simply carbon copies of ongoing grievances regarding PiS appointments and overturned PiS laws. Further, these dissents take a side in the larger political dispute that had engulfed the court—with PiS appointees favoring the party that installed them in office over the decisions taken, both inside and outside of the courtroom, by the Tribunal leadership.

Table 1. Abstract review case with dissenting opinions, 2016

Many of the dissents are also political in another unusual respect, in that they overtly attempt to delegitimize the Tribunal’s outcomes in the eyes of the public. Most of the dissents by the PiS appointees make the claim that the announced majority decision is not an outcome that needs to be followed because the majority either did not rely on new procedural rules that the dissenters thought should be applied—the PiS Constitutional Tribunal amendments—or, alternatively, the majority did rely on past decisions—specifically, case K 47/15—that the dissenters argued lacked legal validity. Both rationales rely on prioritizing PiS’s political message over the Tribunal’s judgments. Both arguments also ask their audience to essentially operate in a parallel legal world, one in which recent Tribunal decisions are not binding and the laws those rulings overturned still are in operation.

III. 2017: A Reversal and a Continuation

Tribunal President Andrzej Rzepliński’s term in office ended in December 2016. The Polish President, Andrzej Duda, subsequently nominated Julia Przyłębska to be the new President of the Tribunal. She, in turn, declared that the main focus of her dissents over the past year—the three contested PiS December appointees: Lech Morawski, Mariusz Muszyński, and Henryk Cioch—would join the Tribunal as full members. She also announced that Muszyński would take on the duties of vice president of the Tribunal, despite the fact that Stanisław Biernat already occupied that role, and continued to do so—though in name only—until his retirement in July 2017.Footnote 85 She later formally accomplished this change in power by placing Biernat on a forced leave of absence, which prevented him from participating in any court cases.

In January 2017, shortly after she became President of the Constitutional Tribunal, Przyłębska entertained a motion from the government’s Prosecutor General to exclude from the court three sitting constitutional Judges: Marek Zubik, Piotr Tuleja, and Stanisław Rymar. The new Prosecutor General, Zbigniew Ziobro, claimed the method the PO-led parliament used to nominate them in 2010 was unconstitutional because parliament had nominated the three together using one nomination resolution, rather than three separate nomination resolutions. This thin reasoning was accepted by Przyłębska until a formal court hearing could be held to decide the matter. Yet, that hearing failed to materialize. Przyłębska canceled a July hearing date without real justification.Footnote 86 And though Tuleja and Rymar were eventually reinstated to the Tribunal in late 2017, Zubik has still not taken part in deciding any cases since his suspension.Footnote 87

Due to these machinations, PiS was in control of the Tribunal by early 2017. Six PiS appointees had been elected to the fifteen-member Tribunal by February 2017. Four sitting PO appointees had then been excluded from deciding cases by the new Tribunal leadership. With this change in the power dynamic came a related change in the authors of the dissenting opinions.

The Tribunal issued final decisions in twelve abstract referrals during the year, a marked decline from previous years. See Figure 1. Of those twelve, six included a dissenting opinion.Footnote 88 As occurred in 2016, most dissenting opinions during the 2017 Tribunal term did not involve the substance of the case under review. Instead, the “old” judges of the Tribunal—and one of the newer appointees who apparently broke from the other PiS judgesFootnote 89—used the dissenting opinion as an outlet to broadcast the procedural maneuverings used by the new leadership to push out disfavored judges and distort the composition of the panels.

For example, in February 2017 Judge Małgorzata Pyziak-Szafnicka filed a dissenting opinion in a case involving the reimbursement of school fees for Polish diplomats serving abroad.Footnote 90 Pyziak-Szafnicka noted at the beginning of her dissent that her position, “does not concern the substantive resolution of the constitutional problem” presented in the case.Footnote 91 Rather, she felt she was compelled to write because, “the panel ruling in the case was shaped in violation of the applicable provisions on the exclusion of judges.”Footnote 92 Earlier that month the Polish Ombudsman, who filed the case on school fees, had requested that two of the Judges in the panel, Mariusz Muszyński and Lech Morawski, recuse themselves due to the outstanding question of whether they were validly elected to the Tribunal. President Przyłębska then selected three recent PiS appointees, including Henryk Cioch, to examine the substance of the Ombudsman’s complaint.Footnote 93

Pyziak-Szafnicka’s dissent focused on this faulty process. She pointed out that Cioch was one of the three Judges—along with Morawski and Muszyński—whose appointments the recusal motion addressed. Thus, Przyłębska created a process in which one of the judges was essentially a judge of his own case. She also noted a very particular detail in her dissent. Pyziak-Szafnicka had tried, in behind-the-scenes discussions, to “convince the other members of the panel to postpone the verdict” in order to resolve the issue.Footnote 94 However, the other panel members—all recent PiS appointees—did not believe there was a need to delay the verdict, thus leading to her decision to write the dissenting opinion. European constitutional courts often are noted for their strong secrecy over the content of deliberations.Footnote 95 This makes Pyziak-Szafnicka’s dissent all the more remarkable: It is a conscious effort to lift the veil and give readers a detailed look at the fundamental conflicts roiling the court. Yet, by doing so her dissent also breaches the general norms of secrecy that are intended to govern court deliberations.

Pyziak-Szafnicka’s dissent provided an early warning of the changes underway at the Tribunal under the new leadership. In fact, Przyłębska had faced criticism from within her own court for rigging the neutral alphabetical ordering system used to determine panels, replacing the “old” judges with her new PiS allies in important cases.Footnote 96 Most of this criticism stayed within the walls of the Tribunal, though in mid-March 2017 four judges filed dissents in a case upholding the constitutionality of 2016 amendments to the law on public assemblies.Footnote 97 President Duda had initiated the case, claiming that the law muddies the waters of lawful assembly and possibly violates the constitutional guarantee of free speech for all civic organizations by granting regional political officials discretion to give preferences to some group assemblies.

The four dissenters—Leon Kieres, Sławomira Wronkowska-Jaśkiewicz, Małgorzata Pyziak-Szafnicka, and Piotr Pszczółkowski—all focused part of their dissent on the substance of the majority’s decision ratifying the limitations on public protest and assembly. Yet, all set aside a significant portion of their dissent to note their dissatisfaction with procedural decisions taken by PiS political actors and the new Tribunal President, and the threat to judicial independence these decisions created. Kieres pointedly noted in his dissent that the Tribunal already determined in December 2015 that three PO nominees had been validly appointed by parliament, yet more than a year later they appeared to have been permanently prevented from entering the court due to the Polish President’s refusal to swear them in to office.Footnote 98

Wronkowska-Jaśkiewicz’s dissent focused on President Przyłębska’s January decision to exclude four sitting judges from participating in this case and all future cases. These decisions, she said, were unfounded in court procedure and allowed Przyłębska to “shape . . . the adjudication panel” illegally.Footnote 99 Judge Pyziak-Szafnicka similarly noted in her dissent that the “violations of law” regarding the exclusion of four judges by the new Tribunal President will “lead to undermining the impartiality of this body.”Footnote 100 She described the Prosecutor General’s application to exclude the three 2010 judges as a pretext used by Przyłębska to remove unfavorable voices, and pointed out the absurdity of forcing Judge Biernat to use his holiday leave time, then using that decision to exclude him from the case on the grounds that he is on holiday.Footnote 101

Judge Piotr Pszczόłkowski, who along with President Przyłębska was one of the initial two PiS judges appointed in December 2015, also dissented to protest the exclusion of Judges Zubik, Tuleja, and Rymar. He questioned the procedure used by the court, particularly the method used to create the panel that would adjudicate the exclusion motion. Pszczόłkowski noted that the same three judges were named by Przyłębska to participate in three related motions submitted by the Prosecutor General, despite the requirement that all panels be chosen by an alphabetical ordering system that should have precluded the same three judges being selected three times in a row. Taking direct aim at the Tribunal leadership, he noted that the neutral panel creation process “is the basic guarantee of objectivity of the Tribunal’s actions,” one that also maintains the Tribunal’s “social authority.”Footnote 102

These dissents continued throughout the year in the dwindling number of cases that still had the “old,” pre-2015 appointees, selected to panels.Footnote 103 For example, in an October 2017 case, Judges Pyziak-Szafnicka and Wronkowska-Jaśkiewicz continued in dissents to speak out against the exclusion of Judges Zubik, Rymar, and Tuleja.Footnote 104 Pyziak-Szafnicka noted directly that her dissent “does not concern the resolution of the case, but the composition,” which, she noted, was “a continuation of the unlawful shaping of the members of the court” through the exclusion of the three.Footnote 105

Overall, ten dissenting opinions were filed in abstract review cases during 2017 (see Table 2). Of those, eight dissents focused on broadcasting procedural irregularities occurring under the new Tribunal leadership—specifically, the removal of disfavored judges from cases by the new Tribunal leadership.Footnote 106 These protests against President Przyłebska’s disqualifications largely stopped after a non-unanimous court changed the Tribunal’s operating rules to require that dissents only discuss the majority’s decision, not the composition of the panels or the court.Footnote 107

Table 2. Abstract review cases with dissenting opinions, 2017

E. Analysis and Conclusion: What Is the Value of Dissent?

What should we make of these remarkable changes in dissent practices? Though dissent as a philosophical concept can take many broad forms,Footnote 108 the traditional purpose of the dissenting or separate opinion in the judicial world has been more limited. Generally, the dissent is intended to express the differences of opinion on fact or law that occurs within a given legal case, and in doing so to explain how a better legal answer could be devised.Footnote 109 The experience in Poland from early 2016 until 2018 shows very few dissenting opinions issued by judges on the Constitutional Tribunal follow these precepts. Few dissents truly engage with the case at issue, either by discussing the law or the policy involved in the court’s outcome. Instead, Tribunal judges have used these opinions largely to broadcast ongoing internal disagreements over the court’s composition, disagreements that have much to do with PiS’s divisive politics. At times, the dissents also appear to have been aimed at undermining the legitimacy of both the majority’s decision and the Tribunal itself as a decision-making body. This might be particularly true for the 2016 dissents.

In fact, the preceding analysis shows there have been two distinct acts in this ongoing court drama. The first was an attack on the court as an institution in 2016, with dissenting opinions seeking to undermine the legitimacy of decisions by treating them as non-binding on the public and the government. The second act was a 2017 response by the established Tribunal judges to various actions of the new PiS-appointed court leadership, notably removing sitting judges from the bench and adding three contested nominees to the court. Still, almost all of the dissents written during this two-year period are out of the norm. Both sides of the divide take issue with the composition of the court, and both argue that the court has taken fundamentally illegitimate actions. Is there a way to create some normative sense of order to these dissents? As detailed below, I argue there is a difference in tone and content that makes the 2016 dissents by PiS appointees particularly troubling discourse for dissenting opinions.

One way of evaluating the two sets of dissents would be to consider the role of the constitutional court within the structure of constitutional democracy, noting specifically the type of politics they are involved in. Garoupa and Ginsburg, among others, have described the courts as straddling the legal and political worlds, with related audiences in both of these spheres.Footnote 110 In fact, constitutional judges do take part in establishing political outcomes in that they are charged with ruling on the policy choices made by democratic governmental actors. The ultimate legitimacy of the constitutional courts relies on the ability of judges to provide accepted legal answers to these often difficult questions.Footnote 111 As Robert DahlFootnote 112 noted many years ago, in this environment it may be asking too much to expect that constitutional judges will avoid politics entirely. Instead, judges rely on providing principled answers to political questions as a way of ensuring broad legitimacy among the public for their outcomes.Footnote 113 Principled answers can be contrasted to nakedly partisan explanations, which perhaps is the dominant mode of explanation used by elected political actors—and perhaps some judges—to create outcomes. The 2017 dissents appear more principled in that they mostly focus on showing the injustice of having the new Tribunal president accept the appointments of three nominees that the court had previously ruled were elected invalidly. They also point out the injustice and absurdity in the decision by the new president to sideline four sitting judges. These writings reflect principles of judicial independence and procedural fairness, though certainly they also reflect the depth of bitter division consuming the court.

In contrast, the 2016 dissents by the new PiS judges appear driven toward advancing a partisan narrative even at the cost of harming the legitimacy of the Tribunal on which they sit. The 2016 dissenters used the opportunity to write separately as a way to expound two key arguments used by their political appointers: First, that the Constitutional Tribunal must negate its earlier constitutional decisions and permit all of PiS’s midnight judges to enter the court, and second, that the Tribunal was obligated to follow PiS’s court-curbing December law before the court examined that law’s constitutionality, and to do otherwise was to break the law itself. In fact, the three early appointees used the remainder of their first year in office to reiterate these points by adding dissenting opinions in cases that had nothing to do with those matters.

Perhaps more importantly, in doing so they also used their ability to write separately in an attempt to undermine the legitimacy of the Tribunal as an institution. Rather than just note their disagreement with the outcome of the previous decisions, all three used their subsequent dissents to state that earlier Tribunal rulings striking down PiS laws were invalid themselves and thus should not be followed or respected by Polish society. Instead, they advocated that the laws struck down by the Tribunal retain their legal effects. This message goes well beyond the conventional boundaries of dissent, becoming instead a call for outright insubordination against the judicial forum of which they are a part. To be sure, the 2016 dissents by PiS appointees were not alone in their efforts to sow doubts about the court. Many 2017 dissents also used strong language to portray the new Tribunal leadership as a potential danger to the hard-won legitimacy of the Tribunal. Yet, despite that strong language, there is also a good deal of truth to those latter charges.

Though certainly not the sole cause, these dissents did coincide with a notable decline in public support for the Constitutional Tribunal. Previous to 2016, the Tribunal was notable for having significantly higher rates of public support than other governmental institutions. CBOS, a major Polish public opinion research firm, reported a public approval rate of forty-four percent for the Tribunal in early 2015.Footnote 114 By the middle of 2017, CBOS reported twenty-six percent approval for the Tribunal, with forty-five percent expressing a negative view of the court.Footnote 115 Jarosław Kaczyński had tried since 2005 to either bring the Constitutional Tribunal within PiS’s orbit, or else bring down the Constitutional Tribunal.Footnote 116 Through their writings during the tumultuous 2016 term, the PiS appointees to the Tribunal only added to the chaos and turmoil that did, indeed, lower the public’s perception of the court.

These questions of judicial tone, civility, and political dealing in judicial writings also become vital for larger questions of democratic theory when applied to courts of final constitutional review. In democratic society, more information about government decision-making is generally viewed as a normative good, largely because such information can be used by citizens to hold government accountable.Footnote 117 By adding new perspectives on the law, dissenting opinions add to the store of information that citizens can access, and thus should generally be a normative good for democratic decision-making and accountability. Yet, as the eminent jurist Roscoe Pound stated in 1953, dissent is valuable only so long as the dissenter expresses reasons, rather than emotions or political attacks.Footnote 118 Similarly, former Australian High Court Justice Michael Kirby has noted that when dissenting opinions take on the “manner of partisan politics,” judicial dissent loses its value to society.Footnote 119 The legitimacy that comes from principled constitutional answers is lost.

Though dissent serves many purposes, a principal value of judicial dissent lies in its ability of foster legitimacy and authority for the court in democratic society.Footnote 120 Through the public dialogues and debates that occur between the majority and minority opinions, courts are able to express democratic values and be a part of the larger dialogue of deliberative democracy in their society.Footnote 121 Yet, as Kirby and others have alluded to, these opinions must still be principled—that is, they must be based in legal reason and be bounded by an appropriate amount of discretion in creating alternative outcomes.Footnote 122 If the dissents are pitched toward the court’s political audience, then the court loses its authority and legitimacy.

With the onset of populist politics in Poland in late 2015, the Constitutional Tribunal has been subjected to forces, both outside and in, that have sought to de-legitimize the court’s outcomes. Inside the court, the dissenting opinion has been used in an attempt to further this de-legitimization and reduce the court to pure politics. Notably, the 2016 dissents broadcast a message of overt defiance against the existing Tribunal leadership, mirroring the divisive politics of their appointing party. The outlet of dissent was also used the next year by judges to broadcast the procedural irregularities undertaken by the new Tribunal leadership—a message that also mirrored the larger political protest against PiS’s dismantling of existing liberal democratic institutions and norms in Poland. Ultimately, the analysis here shows that judges can—and have—used their ability to dissent as a way to participate in the larger social and political battles within society.

Though this analysis focuses on Poland’s court, the developments seen here could be repeated on a broader scale as more democracies experience this same political upheaval. As populist actors continue to gain power, the attempts to reshape the constitutional and social order could bring conflictual politics to the constitutional courts. In this context, the experience of Poland’s constitutional court could be a harbinger of a new, more partisan era of dissenting behavior that should be watched closely.