Since transitioning to multiparty political competition, many African countries have witnessed the formation of new (and evolving) hybrid political orders that involve different sets of actors whose authority derives from customary as well as formal government sources (see Hoehne Reference Hoehne, Zenker and Hoehne2018; Lund Reference Lund2006). In some African countries, the public places its faith in traditional leaders to promote economic well-being and social cohesion as well as to allocate land, mediate disputes and provide symbolic authority for the majority of Africans who reside in rural areas (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2015; Dionne Reference Dionne2012). By contrast, traditional leaders are sometimes viewed as political or vote brokers who exchange votes for continued access to authority and rents (Bonoff Reference Bonoff2016; De Kadt and Larreguy Reference De Kadt and Larreguy2018; Koelble and LiPuma Reference Koelble and LiPuma2011) or ‘decentralized despots’ who impede real democratic development (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996; Ntsebeza Reference Ntsebeza2005).Footnote 1

This article aims to provide insight into these competing hypotheses through more rigorous quantitative evidence as well as inductive and deductive reasoning. Like Carolyn Logan (Reference Logan2013), the article makes use of Round 4 Afrobarometer survey data, but it explicitly accounts for the nested nature of these data by using a multilevel model. Given that the quantitative measures are somewhat crude and limited, the article also undertakes a more fine-grained examination of country cases by drawing on secondary literature and bringing together different insights under a common, yet more nuanced, theoretical rubric.

The overarching goal of this article is to explain why there are high levels of trust in unelected traditional authorities in certain countries while in other countries they are widely distrusted. It also investigates why in certain countries traditional authority has often persisted irrespective of public support and how this links to trust. Given the significant role traditional leaders play in contemporary African states, answering the puzzle about the continuing authority of, and trust in, traditional leaders has critical implications for comparative politics, economic development, sociology and public health.Footnote 2 Moreover, the study has potential importance for many developing democracies in Latin America and Asia, where traditional leaders still carry considerable sway over people's lives (Díaz-Cayeros et al. Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Magaloni and Ruiz-Euler2014; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Kern and Kromrey2016). For example, 61 countries recognize traditional governance and customary law and 57% of the global population resides in countries where customary law and formal law intersect (Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Kern and Kromrey2016: 469).

To date, researchers have offered tentative explanations for what determines the level of trust in traditional leaders and why there is so much variation across countries. However, to the best of my knowledge, this is the first article that examines how historical factors and contemporary country-level and individual-level factors shape trust in traditional leaders across a sample of African countries. Other cross-country studies have focused only on contemporary individual-level variables (Logan Reference Logan2009, Reference Logan2013).Footnote 3

The article presents an interesting set of findings to explain variation in public trust at the country and individual levels. First, trust is higher in cases where French colonial authority did not interfere in traditional structures and allowed traditional leaders to operate outside of the colonial apparatus. This is in stark contrast to the British practice of augmenting the authority of existing traditional leaders to extract on behalf of the Crown within the colonial structure, particularly in Nigeria, Tanzania and South Africa. In other British colonies, indigenous democratic institutions were preserved (e.g. the kgotla in Botswana) and in others pre-existing traditional leaders mobilized local populations and resisted British efforts to weaken them (e.g. Malawi).

Moreover, in most of the former French colonies in the sample (Burkina Faso, Senegal and Mali), there are institutions dating back to the pre-colonial period that promote cross-ethnic coalitions and unity across different groups, and these were left intact to a significant degree under French colonial rule (Chabal Reference Chabal1994; Dunning and Harrison Reference Dunning and Harrison2010; Koter Reference Koter2013). By contrast, in Benin, these pre-colonial institutions were absent and warfare between kingdoms and groups was pronounced. Furthermore, the French colonial authorities in Benin employed a more interventionist approach that pacified conflicts and substantially altered or destroyed traditional structures in many areas (Koter Reference Koter2013; Manning Reference Manning1982).

Second, linked to the conditions created by the pre-colonial and colonial periods, trust is lower in countries where the post-independence state took a hostile stance towards traditional leaders (e.g. Benin, Tanzania) as opposed to a more cooperative symbiotic relationship geared towards building state legitimacy and accountability (e.g. Mali, Senegal).

Third, individual citizens are more likely to trust traditional leaders if they believe that these leaders play an important and positive role in meeting local needs vis-à-vis elected officials. However, there is no quantitative evidence of a substitution effect rooted in relative performance; instead trust in traditional leaders is positively correlated with favourable ratings for government officials. Although making causal (attributive) claims is difficult given the nature of the data, this article's findings constitute important contributions that can be further tested and refined using different data sets and methods.

Theoretical predictions and operationalization of concepts

The central theoretical claim of this article is that colonial-era governance strategies have had enduring effects on public trust in traditional leaders. However, given data and sample size limitations, as well as variation across and within formal colonial governance strategies, it is difficult to operationalize the concept of ‘colonial authority type’ in a way that is analytically tractable. In light of this, I aim to supplement a relatively blunt quantitative measure (British vs French) with a more nuanced qualitative discussion of cases, from which I can derive additional theoretical insights.

I begin in broad strokes. First, the main element of British rule that is arguably the most consequential in determining contemporary levels of trust is when the colonial power carried out the most extreme or exploitative form of indirect rule (often termed suzerain rule). This refers to an arrangement in which ‘tribal states are nominally independent and constitutionally free to order their internal affairs, yet maintain allegiance to an overarching imperial power’ (Naseemullah and Staniland Reference Naseemullah and Staniland2016: 17). Under this regime, the British colonial power mainly empowered or co-opted existing local traditional leaders and institutions to represent, enforce and extract within the colonial state apparatus (Ceesay Reference Ceesay and Jallow2014; Crowder Reference Crowder1964; Lange Reference Lange2009; Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996). Building on work by Mahmood Mamdani (Reference Mamdani1996, Reference Mamdani1999), the word empowered refers to strengthening local chiefly authority by stripping away popular checks and balances that had often existed well before colonial rule and investing despotic authority in local traditional leaders to govern on behalf of the Crown in the countryside. Moreover, under this system, traditional authorities could preserve their customary legal and policy institutions to regulate society in areas under their control (Lange Reference Lange2009; Naseemullah and Staniland Reference Naseemullah and Staniland2016).

The British colonial governance approach in northern Nigeria under Lord Lugard in the early 20th century is the paradigmatic example of suzerain rule. However, it had its origins in the colony of Natal in the second half of the 19th century. Donald Cameron, another British colonial administrator who served under Lugard in the early 1900s, would implement this policy in Tanganyika (modern-day Tanzania) as governor from 1925 to 1931 (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1999: 869). Under this suzerain (indirect rule) system, the British political officer served as an adviser, with chiefs holding substantial authority in governing their areas (Ceesay Reference Ceesay and Jallow2014; Crowder Reference Crowder1964). Often, traditional methods of selecting chiefs were preserved, but the chiefs had to shift allegiance to the British government and collect taxes on its behalf (Ceesay Reference Ceesay and Jallow2014). Peter Cutt Lloyd noted that the Yoruba kings became more powerful under British rule, stating: ‘They could only be deposed by the British administration which often tended to protect them against their own people’ (cited in Crowder Reference Crowder1964: 198; also see Iyeh Reference Iyeh2014). Likewise, the majority of the Fulani emirs agreed to accept British rule as long their authority was preserved (Berry Reference Berry1993: 27). Daniel Adetoritsi Tonwe and Osa Osemwota (Reference Tonwe and Osemwota2013: 131) stated: ‘The traditional rulers were in firm control of their local councils and they tended to be despotic and authoritarian in performing their functions’ – namely, law and order, and colonial tax enforcement. To rule over the stateless or non-hierarchical Igbo, colonial administrators created the chieftaincy and imposed ‘warrant chiefs’, which Chinua Achebe (Reference Achebe2012: 2) describes as ‘a deeply flawed arrangement that effectively confused and corrupted the democratic spirit’ (also see Afigbo Reference Afigbo1972). This system would eventually drive the people to a great revolt against the warrant chiefs (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996: 41). In light of these colonial ruling practices, it is no surprise then that of all Africans in the sample, Nigerians are the least trusting of chiefs.

Although northern Nigeria is the extreme example, this British policy of indirect rule was also applied, to different degrees, in its other colonies (Crowder Reference Crowder1964; Bonoff Reference Bonoff2016). In most of these cases, the colonial administrations had little capacity to implement policy outside the capital city and relied heavily on their clients (i.e. chiefs) to coerce and extract from their subjects. Thus, the more severe form of indirect rule gave chiefs tremendous institutional power within the British colonial regime (Lange Reference Lange2009).

In parallel to Nigeria, South Africa's experience illustrates the destructive nature of indirect rule on public trust in traditional leaders. In Mamdani's (Reference Mamdani1996) book Citizen and Subject, traditional leaders were the link between state and society during colonial and apartheid eras, but were generally more loyal to the state than to rural South Africans. Most importantly, while the traditional leader in the pre-colonial period had to consult (and reach consensus) with his or her counsellors and community to exercise functions, under colonialism a new bureaucratic model was imposed that weakened this system of public debate and accountability. In exchange for greater power, many traditional authorities collaborated with the Union of South Africa government in its segregationist policies.Footnote 4 Similarly, the apartheid system ‘systematically strengthened’ traditional leaders’ power and shifted accountability to the apartheid state (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996: 45). For example, traditional leaders were entrusted to administer the ‘reserves’ by legislation such as the 1951 Bantu Authorities Act, which enhanced their authority but reduced their popular legitimacy (Van Kessel and Oomen Reference Van Kessel and Oomen1997: 563; Oomen Reference Oomen2005). They also controlled associative activities and used their right to levy a tribal tax for their personal benefit instead of spending on local services (Crouzel Reference Crouzel1999). In light of this description, it is unsurprising that the level of public trust in South Africa is the third lowest in the sample.

In contrast to South Africa, traditional authorities in Malawi had a sharply different colonial experience. Partly as a result, people are far more trusting of chiefs in Malawi (see Figure 1). In contrast to many of the other former British colonies, the early situation under British rule in Nyasaland (now Malawi) was not to strengthen chiefs within the colonial structure but to weaken their authority or remove them. However, later on, the publicly sanctioned local authority of chiefs expanded and, as a result, the colonial government had a difficult time shaping local affairs. Some chiefs even got involved in political opposition against the colonial government and mobilized the local population (Eggen Reference Eggen2011). This is a far cry from Mamdani's (Reference Mamdani1996) discussion of chiefs as colonial collaborators or despots in other former British colonies.

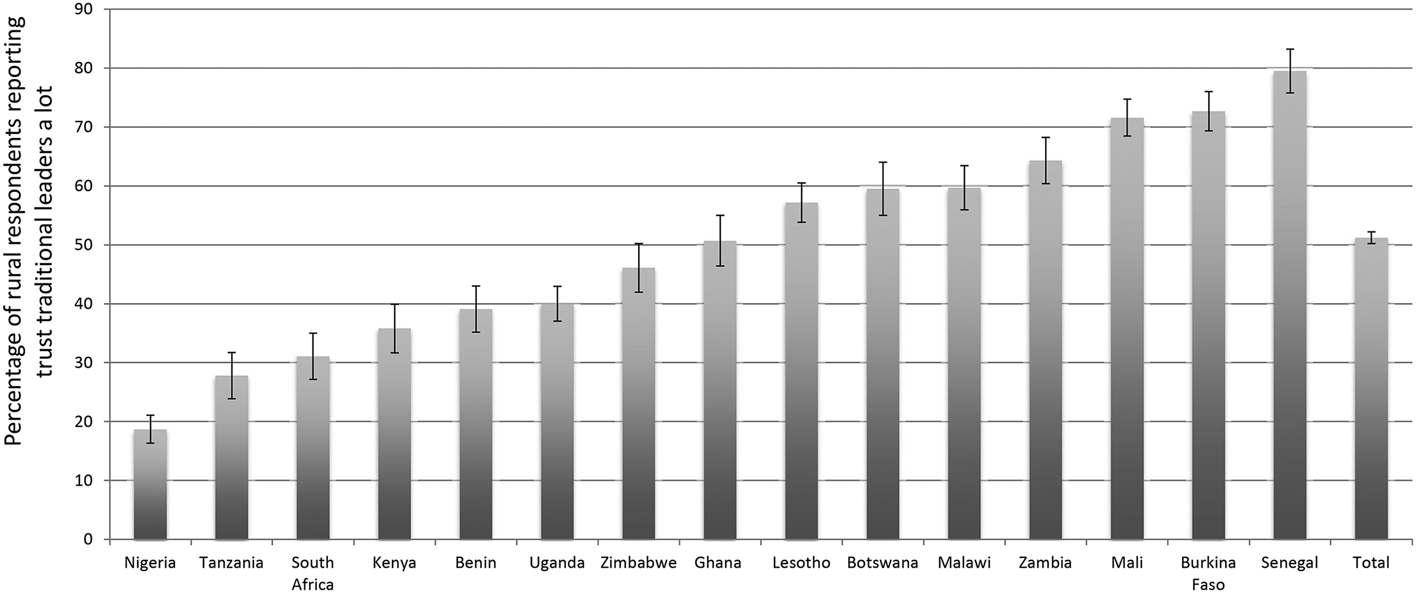

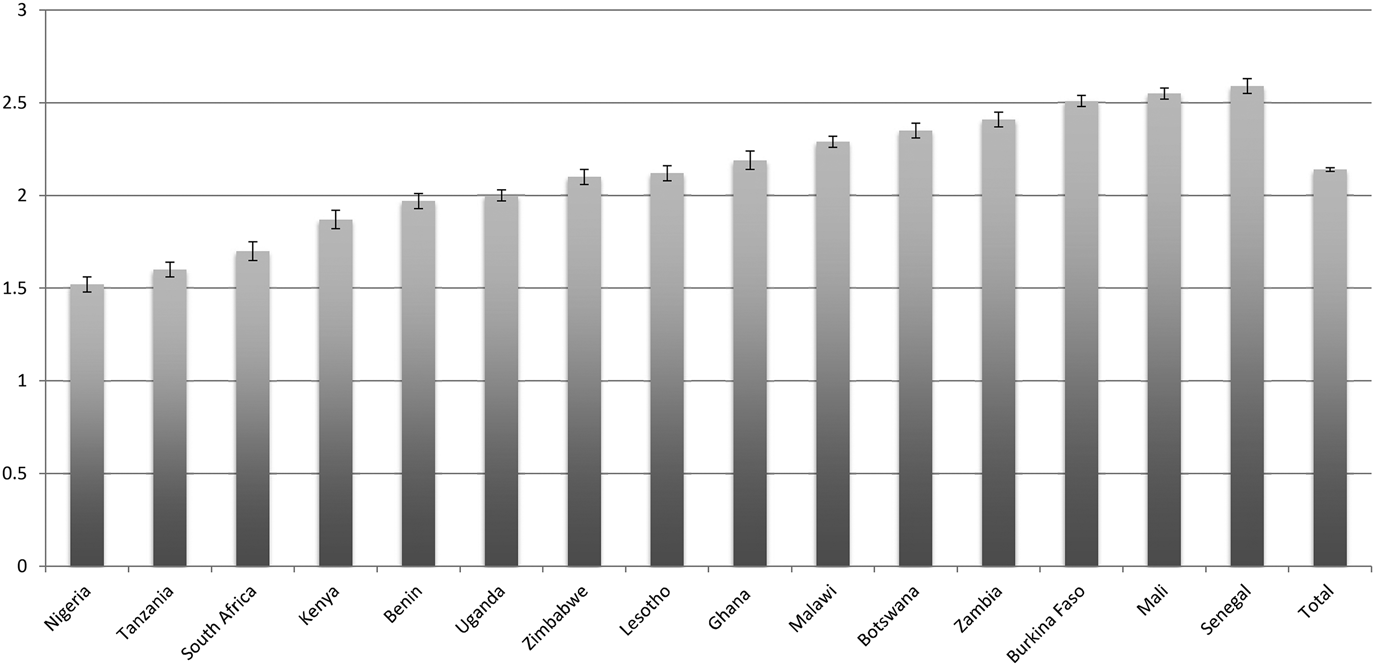

Figure 1. Variation in Percentage of Respondents who Trust ‘Traditional Leaders a Lot’ across Countries. The bars depict 95% confidence intervals. The data are weighted

Similarly, in Botswana, the institution of kgotla (public meetings in the village) persisted more or less intact during the period of the British protectorate of Bechuanaland and was carried over to the newly independent state and then used as a means to mobilize politically (Dipholo et al. Reference Dipholo, Tshishonga and Mafema2014: 18–19).Footnote 5 This experience contrasts with the removal or weakening of public fora and indigenous accountability mechanisms in other countries governed by suzerain rule.

In contrast to the British, the French rarely undertook an extreme indirect rule strategy. The most important reasons why French colonial rule (at least for the majority of former French colonies in the sample) correlates with relatively less distrust between traditional leaders and citizens today are as follows. First, many of the pre-colonial traditional leaders were not embedded in the oppressive colonial hierarchical structure and were less likely to exploit people at the local level in service to the Crown. In countries such as Burkina Faso, Senegal and Mali, the French did not interfere as much (or did so unsuccessfully) in pre-colonial traditional institutions and allowed parallel systems of power to ‘survived [sic] virtually unscathed into the post-colonial era’ (Chabal Reference Chabal1994: 225). One crucial institution is cousinage or ‘joking cousins’, which provides for cross-ethnic ties to form on the basis of surname alliances dating back to the Mali Empire and the reign of Emperor Sundiata Keita in the 13th century, who codified the practice in an oral constitution or charter. Implemented by Emperor Keita to promote peace and unity among different groups within the empire, colonial authorities did not interfere with this informal institution and it persists today in the countries that were part of the empire, including modern-day Burkina Faso, Senegal and Mali (see Dunning and Harrison Reference Dunning and Harrison2010). Benin, by contrast, was not part of the Mali Empire and has no such institution.

Other studies point to the relative autonomy of traditional leaders in Burkina Faso, Senegal and Mali to govern and provide for their subjects outside of the colonial apparatus.Footnote 6 In Senegal, by the early 1900s, many people resented and distrusted the colonial chiefs because the chiefs were appointed by colonial officials and not traditional councils. As a result, many of their subjects shifted their allegiance towards the marabouts (roughly Muslim teacher, leader), who provided a ‘certain religious, social, and economic stability for their disciples’ (Robinson Reference Robinson2004: 187). For example, the Mouride (Sufi) brotherhood's (or Mourides) popularity grew as their marabouts had few ties to the colonial state other than securing the loyalty of their followers and promoting economic productivity through groundnut cultivation. Their followers could rely on them for access to land to grow crops (which they were encouraged to do) but, unlike in Nigeria and South Africa, the traditional leaders did not extract excessive tribute and they also provided education, welfare and security (Cruise O'Brien Reference Cruise O'Brien1971; Robinson Reference Robinson2004). By the First World War, the French recognized the importance of the marabouts in maintaining order and promoting development and thus sought their cooperation. Other research has remarked on the autonomy and authority (outside of the colonial apparatus) of the Muslim brotherhoods and traditional caste-based elites, and the public's enduring respect for these traditional leaders rooted in their higher status and control over certain resources (Chabal Reference Chabal1994; Koter Reference Koter2013: 204–205).

These traditional structures persisted in the post-independence single-party regime in Senegal under President Léopold Sédar Senghor. For example, Catherine Boone (Reference Boone2003a: 367) wrote that because the rural local elite already existed, it was able to use state resources to solidify its status and authority in the Wolof groundnut basin. Dominika Koter (Reference Koter2013) echoes this view, highlighting the consistent cooperation between these elites and the ruling party, which has been characterized as a ‘symbiotic relationship’ known as the ‘Senegalese social contract’ (the latter term quoted from Cruise O'Brien Reference Cruise O'Brien1992, cited in Koter Reference Koter2013: 204). Politicians have been more inclined to partner with existing local traditional leaders, who have long-standing roots and trust in their communities, to build multi-ethnic alliances and avoid ethnic voting blocs. This has likely led to greater public trust in traditional elites today.

Similarly, the Mossi Kingdoms (of the Mossi Empire) in the Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) also retained autonomous power and were mostly treated as a protectorate (Clignet and Foster Reference Clignet and Foster1964; Crowder Reference Crowder1964). Elliott Skinner (Reference Skinner1958) writes that the Mossi Kingdoms were so well organized that the French retained most of the traditional system. The supreme ruler of the Mossi, the Mogho Naba, still plays an influential role as a mediator and unifier who is supposed to remain politically neutral. This institution has continued since the 12th century, and the current Mogho Naba Baongo II is the 37th supreme ruler (BBC News 2015).

Likewise, in Mali, Patrick Chabal (Reference Chabal1994: 175) notes that ‘colonial government had been least efficient’ and was less likely to disrupt the authority of many traditional leaders. For example, Kalifa Keita (Reference Keita1998: 107) writes that the Tuareg strongly resisted colonial prescriptions and largely refused to be brought into the colonial state apparatus. Importantly, the Tuareg ‘have maintained a complex, symbiotic relationship with sedentary agricultural peoples’ (Keita Reference Keita1998: 107). Along with Burkina Faso and Senegal, these countries see the highest levels of trust in the sample (based on Round 4 of the Afrobarometer data, see Figure 1).

Benin's colonial experience contrasts sharply with that of the other former French colonies in the sample. In Benin, the French outlawed the capture and sale of slaves, and restructured the organization of the several existing kingdoms, dismissing or demoting the aristocrats and creating new traditional authorities. The two largest pre-colonial kingdoms, Abomey (Danhomé) and Porto-Novo (Adjacé), were destroyed or greatly undermined by French colonialism as traditional leaders were reduced to honorary figureheads (Koter Reference Koter2013; Manning Reference Manning1982). These moves created disunity and caused tremendous infighting and jockeying for control of land, labour and trade (Manning Reference Manning1982). The long-lasting effect of this colonial policy, in tandem with President Kérékou's hostility towards traditional leaders under the Marxist dictatorship, has led politicians in the multiparty era to form alliances with untrusted traditional leaders or mobilize around ethnic cleavages. Partly as a result, trust levels in Benin are much lower compared with other former French colonies.

The one exception to this policy was in the less populated north of Benin among the Bariba (discussed in Koter Reference Koter2013: 204–205). Because the French did not face threats from the Bariba traditional princes, the colonizers did not interfere with their traditional institutions and made them the chefs de canton. As the Bariba maintained their traditional and royal authority structures, the people viewed their traditional leaders as legitimate. Their popularity stood in distinct contrast to the illegitimacy (in the eyes of the public) of the French-appointed or invented chiefs in the south of the country. This effect persists today in the Afrobarometer data (Rounds 3 and 4); among the Bariba, 60% of the sample trusts traditional leaders ‘a lot’ whereas among the Fon and Adja (where the institution was largely destroyed), only 24% and 17% of respondents trust traditional leaders ‘a lot’ (Koter Reference Koter2013: 205). Thus, where traditional structures remained intact and retained independent authority outside of the French colonial apparatus, there are higher levels of trust today, which is in line with my core argument.

To summarize, under French rule, many traditional leaders in Senegal, Burkina Faso and Mali (and one small part of Benin) retained relatively autonomous power outside of the repressive colonial state. These factors likely led to relatively higher trust levels compared with former British colonies such as Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania, where traditional leaders held great power, and oppressed and extracted from the population on behalf of the Crown within the colonial hierarchical structure.

I argue that the most severe forms of British indirect rule put a major dent in trust in the institution of traditional leadership, forcing politicians in the post-colonial era to form ties with untrusted traditional leaders or to mobilize along ethnic divisions. As Mamdani (Reference Mamdani1999: 868–869) observes, a core component of the colonial policy of indirect rule was to fracture and fragment ethnic identities while bringing them under the control of a common ‘Native Authority’ in a regime of ‘customary’ power. Thus, indirect rule laid the groundwork for future ethnic-based mobilization and division (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1999: 868–869).

By contrast, in most of the former French colonies in the sample, many traditional leaders were able to preserve some trust and moral authority outside of the colonial apparatus. As a result, in these cases, elected politicians in the post-independence era could draw on the existing authority of respected traditional leaders and create broader coalitions instead of mobilizing particular ethnic groups (Chabal Reference Chabal1994; Dunning and Harrison Reference Dunning and Harrison2010; Koter Reference Koter2013).

This article tests the hypothesis about colonial-era practices quantitatively by using former colonial power as a proxy for type of colonial rule. Clearly, this is an imperfect measure but it is frequently used in the literature as the best available option (cf. Kramon Reference Kramon2019; Robinson Reference Robinson2014). The following 11 countries are coded as former British colonies: Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.Footnote 7 The former French colonies are: Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali and Senegal.

Apart from colonial ruling strategies, there are other possible reasons why the public would distrust traditional leaders. In line with colonial destruction of traditional structures, a strong antagonism towards (or destruction of) traditional leadership by post-colonial politicians could also produce such distrust. Tanzania under President Julius Nyerere and Benin under President Mathieu Kérékou are two cases of such state hostility that stand out (for Benin, see Koter Reference Koter2013: 204; for Tanzania, see Bonoff Reference Bonoff2016: 22). I include a control (dummy) variable for these two countries to capture the effect of such policies.Footnote 8

Moving beyond historical variables, the article tests the substitution effect hypothesis that people trust traditional leaders more when elected officials are performing poorly (as discussed in Logan Reference Logan2013). To this end, I include variables that capture direct self-reported assessments of the performance of local government officials, MPs and the president.

Apart from the primary explanatory variables of interest, the article tests whether there is a country-level modernization influence based on the natural log of per capita gross domestic product in 2008.Footnote 9 In line with the classic modernization thesis (Lipset Reference Lipset1959), the expectation is that wealthier countries will be less trusting of traditional leaders because of the wider influence of mass media, higher education, meritocratic procedures, modern technologies and democratic values.

At the individual level, I employ the standard battery of control variables including age, gender, level of education and employment status (and urban or rural residence when the sample is not restricted to rural dwellers).Footnote 10 Education level is self-reported on a nine-point scale from no formal schooling to postgraduate education. An individual is coded as employed if she has full-time employment (see Logan Reference Logan2009, Logan Reference Logan2013; Robinson Reference Robinson2014).

The models also include variables to capture the (perceived) authority of traditional leaders with regard to different functions: managing schools, managing health clinics, collecting taxes, solving disputes, allocating land and maintaining law and order.Footnote 11 The intuition behind the inclusion of such variables is that trust is plausibly linked to authority, and if traditional leaders are perceived to be the actors primarily responsible for executing these functions, people under their jurisdiction may be more likely to trust them.

Numerous scholars have highlighted that traditional leaders remain critical actors in dispute resolution and development (Logan Reference Logan2013; Williams Reference Williams2010). Based primarily on research in Zambia, Kate Baldwin (Reference Baldwin2015: 11) offers a ‘development-broker theory’ that postulates that traditional leaders ‘facilitate the delivery of goods and services’ by increasing the accountability of elected officials to their constituents.

In parallel, research in Botswana – a country with statistically identical levels of trust to Zambia – suggests that the government views traditional authority as an essential partner in promoting local development and legitimizing the state (Dipholo et al. Reference Dipholo, Tshishonga and Mafema2014). More precisely, elected officials need the support of traditional leaders to draft and implement local (district) development plans (Sharma Reference Sharma2005: 11). In this regard, the kgotla institution plays an important role in political mobilization and in facilitating consultation and participation in this development planning process (Dipholo et al. Reference Dipholo, Tshishonga and Mafema2014; Sharma Reference Sharma2005).

In Malawi, another former British colony with relatively higher trust levels, the strength of traditional authorities in the contemporary era is probably a crucial factor. Importantly, chiefs in Malawi became the principal local authorities in the absence of councillors at community and district levels, particularly from 1992 to 2000, when all sitting councillors had to give up their positions during the transition to multiparty democracy because they were all affiliated with the Malawi Congress Party (Chinsinga Reference Chinsinga2006; Hussein Reference Hussein2010). Traditional leaders in Malawi are popular, accessible and readily available to address a range of problems, including providing advice and solutions with respect to disputes, inheritance, family issues, law enforcement and development projects (Hussein Reference Hussein2010: 97). Blessings Chinsinga (Reference Chinsinga2006: 271) stated: ‘in the eyes of the rural communities, customary authorities are considered far more legitimate catalysts for development and change compared to, for example, MPs and councilors’.

The system in South Africa presents a contrast, wherein elected ward councillors typically wield far more power and are the main point of contact for most issues in local governance. Although traditional leaders’ permission is needed to implement development projects in their areas and retain some symbolic authority, they are less likely to be viewed as the focal actors in development and service delivery.Footnote 12

With regard to land allocation, Baldwin's (Reference Baldwin2014) article implies that there might be a positive association when land allocation authority is tied to building cross-ethnic coalitions and thus to broader support from traditional leaders across different ethnic groups. In parallel, Koter (Reference Koter2013: 201–202) describes how customary landholders in Senegal such as the marabout and toorobe derived substantial and enduring authority from – and cultivated relationships with citizens based on – their control over land allocation.

Finally, an additional innovation of this study is to include a dummy variable for whether the respondent perceives the interviewer to come from the government. I hypothesize that respondents who think the government is interviewing them may over-report trust in traditional leaders because these leaders are often wedded to the state (compared with respondents who do not think the government is interviewing them). I argue that respondents do this because they are fearful of state reprisals.Footnote 13

Model selection and data

In Afrobarometer surveys, individual-level observations (obtained from an individual within a visited household) are nested within clusters by design (i.e. countries). A multilevel model accounts for this clustering and is the appropriate choice if higher levels affect individual-level outcomes (i.e. clustering matters). The dependent variable comes from a question in the Afrobarometer survey: ‘How much do you trust each of the following, or haven't you heard enough about them to say: Traditional leaders.’ The response options are: ‘a lot’, ‘somewhat’, ‘just a little’, ‘not at all’.Footnote 14 The concept of ‘trust’ is not formally defined by the Afrobarometer survey. Thus, one can only cautiously speculate about what this concept and the different categories on the self-reported trust scale actually mean (to people), which are likely to vary between individuals as well as across local contexts.Footnote 15 The aim of this article is to conduct a quantitative empirical examination of how different country-level factors and individual characteristics are linked to self-reported levels of trust. The coefficient estimates reflect the ‘average’ association between these different factors and trust levels across a sample of 12,370 rural dwellers in 15 countries.

For reasons outlined in the previous section, it is theoretically likely that country-level attributes (along with individual-level factors) will affect individual responses.Footnote 16 The use of a multilevel model (as opposed to an individual-level one) is a significant improvement over previous studies. Although the cross-sectional regression model does not allow for strong claims about causality, the results show important and new associations among the variables of interest. The model assumes that unobserved contextual factors at the country level (which are captured in the random intercepts) are uncorrelated with the included independent variables. A violation of this assumption could result in heterogeneity bias, though.Footnote 17

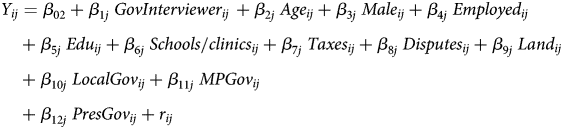

The individual (level 1) model is formalized as:Footnote 18

$$\eqalign{& Y_{ij} = \beta _{02} + \beta _{1j}\;GovInterviewer_{ij}\,+ \beta _{2j}\;Age_{ij} + \beta _{3j}\;Male_{ij} + \beta _{4j}\;Employed_{ij} \cr & \quad + \beta _{5j}\;Edu_{ij} + \beta _{6j}\;Schools/clinics_{ij} + \beta _{7j}\;Taxes_{ij} + \beta _{8j}\;Disputes_{ij} + \beta _{9j}\;Land_{ij} \cr & \quad + \beta _{10j}\;LocalGov_{ij} + \beta _{11j}\;MPGov_{ij} \cr & \quad + \beta _{12j}\;PresGov_{ij} + r_{ij}} $$

$$\eqalign{& Y_{ij} = \beta _{02} + \beta _{1j}\;GovInterviewer_{ij}\,+ \beta _{2j}\;Age_{ij} + \beta _{3j}\;Male_{ij} + \beta _{4j}\;Employed_{ij} \cr & \quad + \beta _{5j}\;Edu_{ij} + \beta _{6j}\;Schools/clinics_{ij} + \beta _{7j}\;Taxes_{ij} + \beta _{8j}\;Disputes_{ij} + \beta _{9j}\;Land_{ij} \cr & \quad + \beta _{10j}\;LocalGov_{ij} + \beta _{11j}\;MPGov_{ij} \cr & \quad + \beta _{12j}\;PresGov_{ij} + r_{ij}} $$where Y ij is the individual-level indicator for trust in traditional leaders for each individual i, from country j; β 0j is the individual-level intercept; β 1j through β 12j are the coefficients for the 12 individual-level variables; and r ij is the individual-level error term.

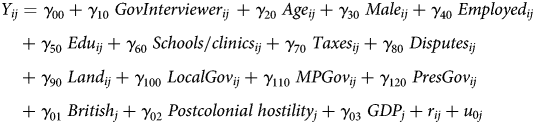

At the second level of the model, country-level variables are included to model the individual-level intercept as a function of country conditions:

where β 0j is the country-level intercept, γ 01 through γ 03 are the coefficients for the three country-level variables; and u 0j is the country-level random error term.

Combining the two levels, the multilevel model with fixed and random components can be formalized as follows:

$$\eqalign{& Y_{ij} = \gamma _{00} + \gamma _{10}\;GovInterviewer_{ij}\,+ \gamma _{20}\;Age_{ij} + \gamma _{30}\;Male_{ij} + \gamma _{40}\;Employed_{ij} \cr & \quad + \gamma _{50}\;Edu_{ij} + \gamma _{60}\;Schools/clinics_{ij} + \gamma _{70}\;Taxes_{ij} + \gamma _{80}\;Disputes_{ij} \cr & \quad + \gamma _{90}\;Land_{ij} + \gamma _{100}\;LocalGov_{ij} + \gamma _{110}\;MPGov_{ij} + \gamma _{120}\;PresGov_{ij} \cr & \quad + \gamma _{01}\;British_j + \gamma _{02}\;Postcolonial\;hostility_j + \gamma _{03}\;GDP_j + r_{ij} + u_{0j}} $$

$$\eqalign{& Y_{ij} = \gamma _{00} + \gamma _{10}\;GovInterviewer_{ij}\,+ \gamma _{20}\;Age_{ij} + \gamma _{30}\;Male_{ij} + \gamma _{40}\;Employed_{ij} \cr & \quad + \gamma _{50}\;Edu_{ij} + \gamma _{60}\;Schools/clinics_{ij} + \gamma _{70}\;Taxes_{ij} + \gamma _{80}\;Disputes_{ij} \cr & \quad + \gamma _{90}\;Land_{ij} + \gamma _{100}\;LocalGov_{ij} + \gamma _{110}\;MPGov_{ij} + \gamma _{120}\;PresGov_{ij} \cr & \quad + \gamma _{01}\;British_j + \gamma _{02}\;Postcolonial\;hostility_j + \gamma _{03}\;GDP_j + r_{ij} + u_{0j}} $$In the next section, I present descriptive statistics and regression results based on one pooled wave of the Afrobarometer Round 4 data to estimate a model for the dependent variable of trust in traditional leaders.Footnote 19 The countries included in the pooled data set are: Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Roughly 1,200 households are interviewed in each country, with the exceptions of Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda (wherein roughly 2,400 households are interviewed). For different reasons, I exclude five countries from the regression analysis.Footnote 20 Although the sample of 15 countries is small for a multilevel model, the threat of biased estimates is far more pronounced with fewer than 15 countries (Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2013: 754).

Descriptive statistics

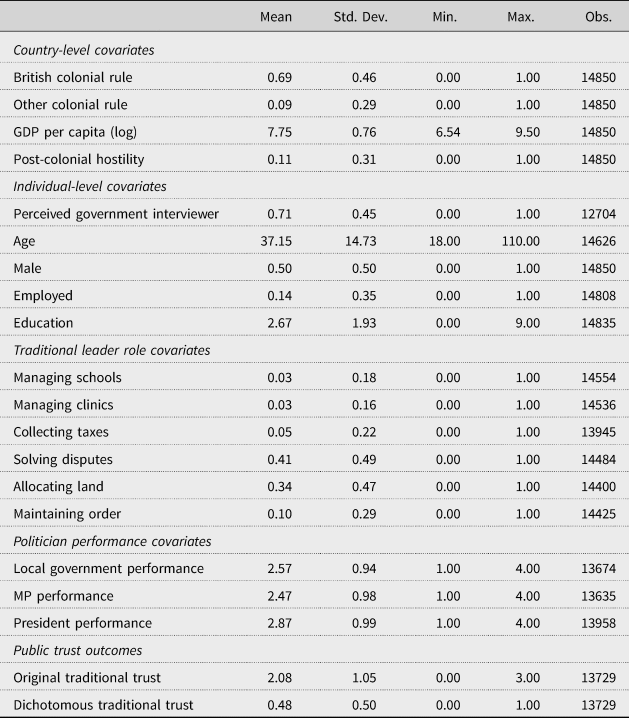

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the full Afrobarometer sample of 17 countries for which the data are available (Cape Verde, Mozambique and Madagascar are excluded due to data limitations). Sixty-nine per cent of respondents live in a former British colony, 22% reside in a former French colony, while 9% live in either Namibia or Liberia. Figure 2 presents the data for the dependent variable of trust in traditional leaders. In the sample of 15 countries used in the regression model (excluding Namibia and Liberia due to former colonial status), approximately 51% of 12,370 rural respondents reported trusting traditional authorities ‘a lot’.Footnote 21 Figure 1 shows a great deal of variation across countries, with a point estimate of 19% for Nigeria all the way to 80% for Senegal. Although these two country estimates are statistically different from all other countries, neither country's trust level is substantially removed from its nearest neighbours’. Tanzania and South Africa, for example, are not far behind Nigeria at 28% and 31% while Burkina Faso and Mali are not far behind Senegal at 73% and 72%. With the exception of Benin, the former French colonies are clustered at the high end of the trust spectrum while the former British colonies are spread from the low to upper-middle parts of the distribution. The results are roughly similar when using the mean score for the non-collapsed four ordered categories (see Figure 2).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

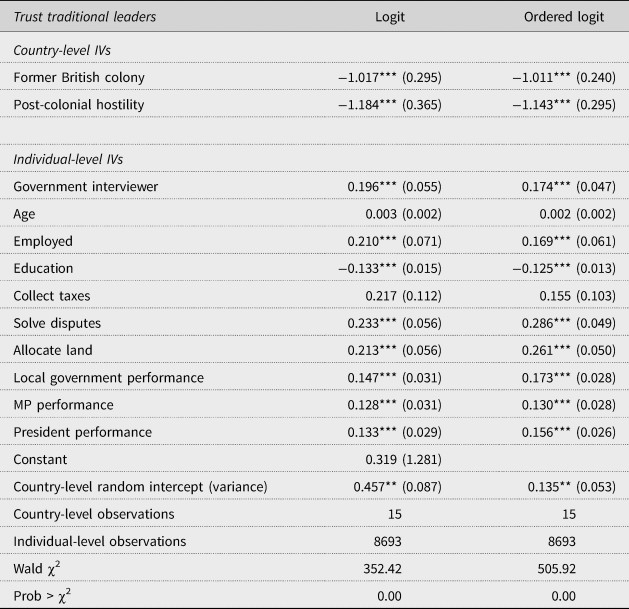

Figure 2. Variation in the Mean Trust Score in Traditional Leaders for the Four Ordered Categories (0, 1, 2, 3). The bars depict 95% confidence intervals. The data are weighted

Regression results

The first column in Table 2 presents regression results for the benchmark multilevel logit model with the collapsed binary dependent variable being whether respondents trust traditional leaders ‘a lot’ vs all other response options (i.e. ‘not at all’, ‘just a little’, ‘somewhat’). ‘A lot’ seemed to be the appropriate comparison category given that this article is interested in determining what leads individuals to place a high level of trust in their traditional leaders instead of the middling response categories, which correspond to lukewarm support. The binary variable also provides for ease of interpretation. In column 2, I present results for the non-collapsed ordered logit to show that the effects are consistent (although slightly more difficult to interpret). For the ordered logit model, the interpretation corresponds to a change in the odds of being above a particular category of trust. The effects are only slightly reduced for all estimated coefficients with the ordinal dependent variable (DV) and nearly identical for the higher-level variables. All of these models are run using the raw scores.Footnote 22 Given the nature of the response variables (binary and ordinal), multilevel logistic regression is the appropriate choice (Liu Reference Liu2016). Logistic regression models do require certain assumptions, but they are far less restrictive than the linear probability model.Footnote 23 For example, the logit models assume that the independent variables are linearly related to the log odds. They also typically require a large sample size. One common robustness check is to test whether results are sensitive to dropping individual countries because the sample of country cases is only 15. I thus rerun the regressions removing each country from the sample one at a time and find that the results are highly consistent.Footnote 24

Table 2. Multilevel Model (raw scores)

Notes: ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. Standard errors in parentheses. Cape Verde, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia and Liberia omitted. The coefficients on GDP per capita and gender are insignificant and not shown.

For both logit models, the intercept variance is positive and statistically significant, suggesting a high level of between-cluster (country) variation in the outcome score (or the variance of the unadjusted cluster means) (Enders and Tofighi Reference Enders and Tofighi2007: 127).

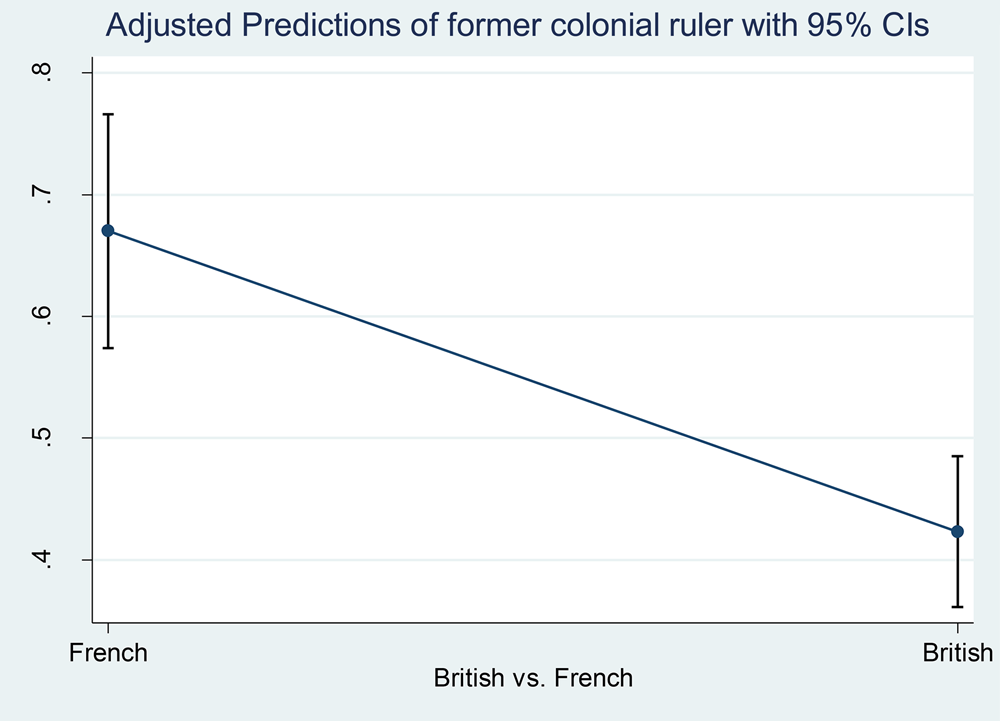

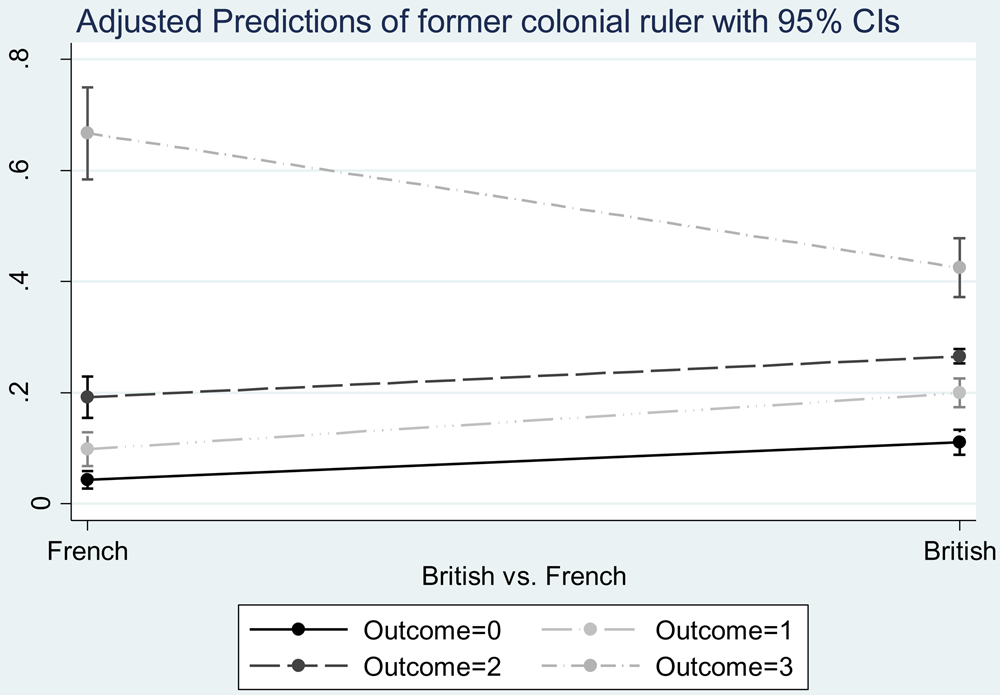

For the country-level predictors, the colonial-era effects align with the earlier theoretical discussion; there is a strong negative association between former British colony and trust (and implicitly a positive association between former French colony and trust). This effect is substantial: an individual is 2.77 times less likely to trust traditional leaders a lot if she lives in a former British colony (compared with a French colony).Footnote 25 Another way to interpret this effect is by computing the estimated probability for the binary predictor variable (British vs French) while holding the other predictor variables at their means. Figure 3 presents the estimated probabilities for the dichotomous response trust variable (0 = all other options or 1 = trust a lot) for the binary predictor (British vs French) when holding all other predictors constant at their means. With all other predictors held constant at their means, the estimated probability of being in the ‘trust a lot’ response category is 0.67 for individuals in a former French colony whereas it is 0.42 for individuals residing in former British colonies.Footnote 26 Figure 4 presents the estimated probabilities for the four categories of the ordinal response trust variable when Y = 0, 1, 2, 3 for the binary predictor (British vs French) when holding all other predictors constant at their means. As is apparent in the figure, the estimated probabilities of being in outcome 3 (trust a lot) do not change from the collapsed logit model. What the figure reveals are the slightly higher probabilities of being in the other three categories for individuals in former British colonies with all other predictors held at their means.

Figure 3. Estimated Probabilities for the Dichotomous ‘Trust Traditional Leaders a Lot’ Response Variable for the Binary Predictor (British vs French) when Holding all Other Predictors Constant at their Means

Figure 4. Estimated Probabilities for the Four Categories of the Ordinal Response Variable (Y = 0, 1, 2, 3) for the Binary Predictor (British vs French) when Holding All Other Predictors Constant at their Means

There is also a negative and statistically significant coefficient on the dummy variable for a hostile policy towards traditional leaders in the post-colonial single-party era. Substantively, an individual is 3.27 times less likely to trust traditional leaders a lot if she resides in a country where the post-colonial single-party regime attempted to root out traditional leaders.

The other country-level coefficient, for logged GDP per capita, is insignificant (not shown), suggesting that there is not a country-level modernization effect on individual trust in traditional authority. This is an interesting finding that collides with an implication from the classic modernization thesis; a country's level of wealth is not associated with (less) trust in traditional leaders.

At the individual level, possessing more education is negatively correlated with trust in traditional leaders, while having a full-time job is positively correlated.Footnote 27 The latter result is interesting, and could suggest that employment in rural areas is contingent on connections with traditional leaders. Another interesting result is the lack of a statistically significant association between one's gender and trust in traditional leaders (not shown). It is surprising because this contemporary male-dominated institution generally disadvantages women. In the pre-colonial era, in many societies, women had far more power in traditional institutions and often there were matriarchal spheres of authority, which were largely crushed by colonial rule.

Apart from individual characteristics, the perceived authority of traditional leaders is positively linked to trust, which is in line with some of the theoretical predictions discussed earlier. Regardless of model specification, there are invariably statistically significant positive estimated coefficients on the indicators for primary responsibility for land allocation and solving disputes.Footnote 28 These effects are smaller than the country-level covariate effects but still sizeable; individuals are around 1.25 times more likely to trust traditional leaders a lot if they believe that the traditional leader has primary responsibility for either of these functions (vs. not having primary responsibility).Footnote 29 In a few specifications, the positive estimated coefficient on collecting taxes is statistically significant at the 90% level.Footnote 30 These results suggest that when traditional leaders are primarily responsible for these governance and development-related functions, rural dwellers are, on average, more likely to report a high degree of trust.

Performance and accountability measures are also crucial. Some theories would suggest that traditional leaders’ legitimacy would be greater when citizens have little trust in elected officials who are perceived to be performing poorly (i.e. a substitution effect). However, the regression results show that positive ratings of elected officials (i.e. local government, MP and presidential performance) correspond to more trust in chiefs.Footnote 31 However, additional theorizing is needed to explain why the strong performance of one institution is positively associated with trust in the other (in other words, why there appears to be a complementary relationship on average).

My interpretation of this result is that many citizens rate these formal and informal governance institutions favourably (or unfavourably) because both institutions are often incorporated into the state. In other words, if people think elected officials are accountable and delivering to their constituents, they are also more likely to trust traditional leaders because they are also linked to the same state apparatus. Conversely, if elected officials are perceived as unaccountable and deficient in service provision, the public, on average, is likely to rate them unfavourably but also trust traditional leaders less. Although this is a novel argument, it is not incompatible with existing empirical work that shows that traditional leaders serve developmental roles in the case of Zambia (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2015) or vote-brokering functions in the case of South Africa (De Kadt and Larreguy Reference De Kadt and Larreguy2018). Additional support for my theory can be found in response biases based on the perceived government identity of the interviewer; perceiving the interviewer to come from the government corresponds to more trust in traditional leaders (see Table 2) and more favourable ratings of elected officials (results now shown).

This is not to say that this part of the argument applies to all countries or to all regions within countries. As scholars of hybrid governance have noted, the local nature of competition and cooperation between state and chieftaincy institutions is complex and dynamic as both sets of agents continually negotiate to maintain political power and control (Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan Reference Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan2003; Hoehne Reference Hoehne, Zenker and Hoehne2018; Lund Reference Lund2006). As a result, people may rely on different state and non-state institutions for different purposes as a means of obtaining greater benefits (Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan Reference Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan2003; Hoehne Reference Hoehne, Zenker and Hoehne2018). It is also important to note that traditional leaders are not recognized or aligned with the state in certain countries (e.g. Muriaas Reference Muriaas2011, on Uganda) or in certain areas within countries (e.g. Tignor Reference Tignor1971, on differences within Kenya and Nigeria). In some cases, prominent chiefs may exercise political power within the opposition party.Footnote 32 In addition, many people, particularly in competitive systems, belong to the opposition party and may be opposed to the state and traditional leadership. Moreover, many people may be opposed to traditional leadership, but allied with the state. However, the average associations in this sample of countries are statistically significant and robust to changes in centring and modelling approaches. Future research would be useful in drawing out the differences across countries and within them, as differences may appear along regional or tribal lines or other dimensions (see Boone Reference Boone2003a, Reference Boone2003b; Tignor Reference Tignor1971).

Taken together, these results show that, in many countries, reported trust in traditional authorities is partly driven by colonial ruling strategies (and their residual effects), post-colonial policies towards traditional leaders, and the contemporary role of traditional leaders in the multiparty democratic era.

Conclusions

This article was motivated by a desire to understand the factors that explain the large degree of variation in reported public trust in traditional authorities across African countries in the multiparty democratic era. In so doing, it shed light on a crucial puzzle about why unelected traditional leaders are trusted or distrusted actors in different African countries.

It presented a novel argument and an important set of findings. First, a multilevel modelling approach provided evidence that the colonial-era practices of the British and the French have had an enduring impact on trust in traditional leaders. The British Crown's predominant colonial policy of indirect rule through empowered indigenous leaders appears to have had a long-lasting negative effect on public trust in the institution of traditional leadership. By contrast, traditional leaders in most of the former French colonies in the sample maintained their institutions and a large degree of autonomous authority (separate from the co-opting influence of the colonial apparatus), and this correlates with greater trust in the contemporary democratic period. The discussion of country cases brings to light differences among former British colonies with variations in degree and form of rule and among former French colonies, which helps explain some of the variation in public trust within the same former colonial power.

In addition, the article shows that trust is partly explained by whether traditional leaders play a positive and important role in governance and development vis-à-vis elected officials. Moreover, instead of a trade-off between the accountability of traditional leaders and elected officials, trust (or distrust) appears to depend on the performance of both institutions because they are frequently incorporated into the same state apparatus.

While the pooled regression results of this article are based on survey data from 15 African countries, the findings may not reflect the reality in all the countries in the data set or in countries outside of the sample. In light of this, the study points the way to several avenues for future research. First, it identified a few important predictors (or correlates) of trust: colonial ruling strategy, post-colonial hostility and the contemporary role of traditional leaders vis-à-vis elected politicians. Future research using new data could investigate and potentially provide more empirical support for the mechanisms implied by the main argument. The construction of fine-grained cross-country and within-country data sets could be used to build more evidence on the effect of colonial governance strategies. Second, although the results presented here are consistent with the argument, there are specific countries and areas within countries where aspects of the argument do not apply, and additional research is needed to explain the different patterns in these cases. This article's discussion of cases was brief and illustrative, and future work may wish to engage critically with these and other cases with respect to the arguments advanced here. Moreover, because the sample only covers 15 African countries, further (out-of-sample) cases on the continent should be examined to test the external validity of the theory.

Finally, although this article has focused on the experiences of a sample of African countries, the arguments about colonial ruling strategies and the contemporary role of traditional leaders in local development may apply beyond Africa in other developing democracies where traditional leadership remains a critical governance institution. Testing these arguments and refining the theory using cases in Latin America and Asia will be a useful avenue for future research.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Nadège Compaoré, Salvador Forquilha, Theodore Kahn, the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (CoGTA) in South Africa and multiple anonymous reviewers at Government and Opposition and other journals for their suggestions. Some of the research and writing was completed under the auspices of a George L. Abernethy Doctoral Research Fellowship with additional travel support from the Fred Hood Research Fund.