Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

1 Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue (BJS 36; Chico: Scholars Press, 1982).Google Scholar

2 CII 400, 581, 590, 597, 692, 731c; and SEG 27 (1977) no. 1201.

3 Brooten, Women Leaders, 41–55.

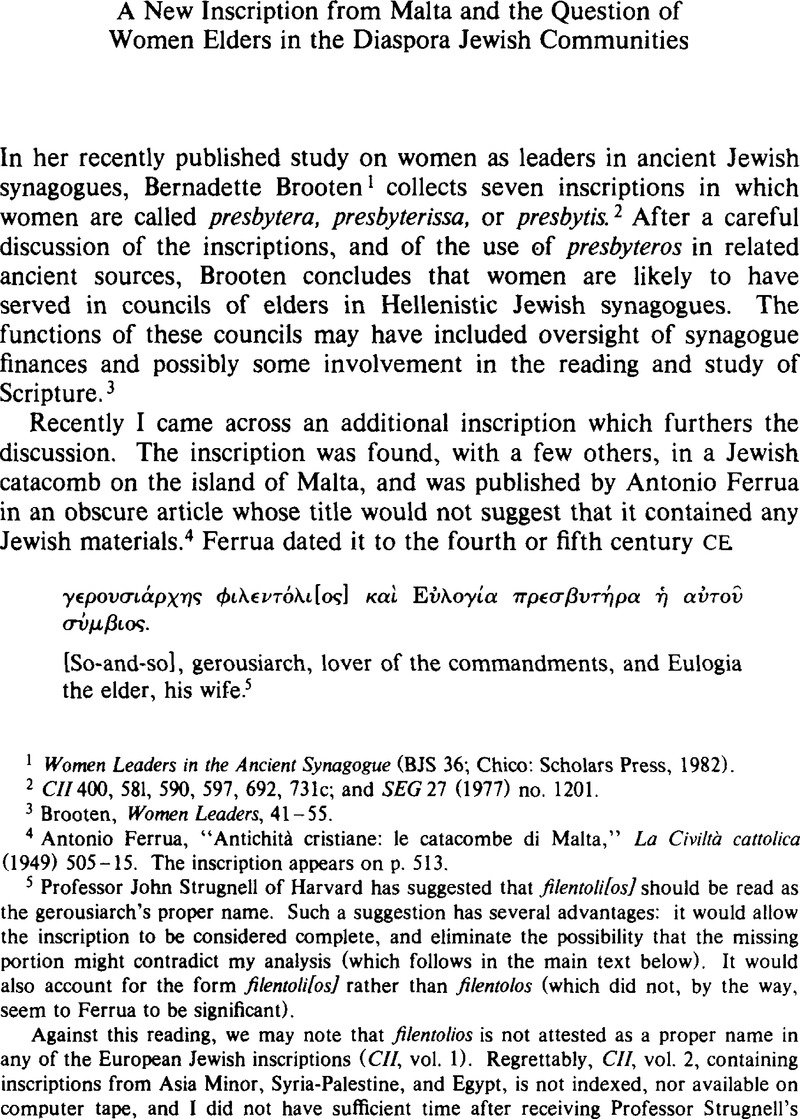

4 Ferrua, Antonio, “Antichitá cristiane: le catacombe di Malta,” La civiltà cattolica (1949) 505–15.Google Scholar The inscription appears on p. 513.

5 Professor John Strugnell of Harvard has suggested that filentoli[os] should be read as the gerousiarch's proper name. Such a suggestion has several advantages: it would allow the inscription to be considered complete, and eliminate the possibility that the missing portion might contradict my analysis (which follows in the main text below). It would also account for the form filentoli[os] rather than filentolos (which did not, by the way, seem to Ferrua to be significant).

Against this reading, we may note that filentolios is not attested as a proper name in any of the European Jewish inscriptions (CII, vol. 1). Regrettably, CII, vol. 2, containing inscriptions from Asia Minor, Syria-Palestine, and Egypt, is not indexed, nor available on computer tape, and I did not have sufficient time after receiving Professor Strugnell's suggestion to search the volume (and other Jewish inscriptions not included in CII) again manually.

Filentolos occurs twice (and probably a third time) in the European inscriptions (CII 132, 509, and is conjectured for 203). In CII 132 it refers to a woman, Crispina, in the masculine form; in CII 509 to a man, Pancharios, who is also called pater synagōgēs and filolaos. The gender of the individual in CII 203 is unknown. We find in CII 482 a Latin transcription filentolia, for the Greek φιλευτολϪ describing a woman, Victorina. The term does not occur in the Jewish inscriptions from Egypt as either a name or an adjective, nor in the inscriptions included by Lifshitz (see below, n. 11), nor in Philo, nor in Josephus.

Even if the name is attested for this period, the word order in our present inscription mitigates against such a reading here. In virtually all the Jewish inscriptions, the name of the individual precedes the title, not the reverse. This is the case for all the European gerousiarch inscriptions. The term gerousiarch is often followed by the name of the community in which he held office, but I can find no instances where an individual is called “gerousiarch so-and-so.”

Finally, as Professor Strugnell noted to me, whether filentoli[os] describes the gerousiarch, or presents his proper name, does not materially affect my analysis of this inscription; it would, in fact, only strengthen the argument that Eulogia of Malta was a synagogue official in her own right.

6 Ferrua, in his discussion, took filentolios to be identical with filentolos. While this is grammatically unusual, it is not without precedent, e.g., filokatharios and filokatharos (Liddell-Scott, p. 1936).

7 Ibid., 514. The second inscription is significant for the study of Jewish women, referring to one Dionysia, who was also called Irene. Goodenough thinks her second name may be a “ritualistic name, the name of a blessed state” (Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period [New York: Pantheon, 1953] 2. 57–58),Google Scholar which he thinks may also be true of the name Eulogia.

8 CII 400, 597, 692, 731c; SEG 27 (1977) 1201.

9 Brooten, Women Leaders, 44.

10 Ibid.

11 See Brooten's discussion of Sara Ura (CII 400), p. 45, for consideration of one instance where the term might have this meaning.

12 CII 739, also published by Lifshitz, B., Donateurs et fondateurs dans les synagogues juives (Paris: Gabalda et Cie, 1967) no. 14Google Scholar; see also Donateurs, nos. 37, 58.

13 CII 378. See also Leon's, Harry J. translation and commentary The Jews of Ancient Rome (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1960) 321Google Scholar; Donateurs, no. 32; CII 735 = Donateurs, no. 82.

14 CII 380. But see Leon's translations and notes in Jews of Ancient Rome, 321–22. CII 723 supports this reading more clearly.

15 CII 380; Leon, Jews of Ancient Rome, 322.

16 Brooten, Women Leaders, 43.

17 See, e.g., Hopkins, Keith, “On the Probable Age Structure of the Roman Population,” Population Studies 20 (1966) 245–64CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Blumenkranz, Bernhard, “Quelques notations demographiques sur les Juifs de Rome des premiers siècles,” StPatr 79 (1961) 341–47Google Scholar; Boyaval, B., “Sur mortalité et fecondité feminines dans l'Égypte greco-romaine,” ZPE 28 (1978) 193–98.Google Scholar

18 Brooten, Women Leaders, 42.

19 E.g., CII 301, 368, 408, 425, and 803 = Donateurs, no. 38. Other inscriptions mention the title gerousiarch without relating it to a specific community.

20 Ibid., 39.

21 CII 9, 95, 106, 119, 147, 189, 301, 353, 368, 405, 408, 425, 504, 511, 600, 733b.

22 CII 95, 106, 147, 511, 733b.

23 CII 166, 619d. For the history of the interpretation of these inscriptions, and for the refutation of the typical scholarly consensus that “mother of the synagogue” refers to the wife of a father of the synagogue, or connotes only some “honorary” status, see Brooten, Women Leaders, 57–72.

24 Ibid., 7ff.

25 Ibid., 9.

26 I am indebted to the National Endowment for the Humanities, for a year-long fellowship during 1982–83, which enabled me to do substantial research on women in Greek-speaking Jewish communities in antiquity, of which this article represents a small portion. I would also like to thank the Department of Religion at Princeton University, for welcoming me as Visiting Fellow during this period, and the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania for extending to me the privileges of a Visiting Fellow from 1982 to the present. Finally, A. Thomas Kraabel and Bernadette Brooten provided helpful comments on previous drafts of this paper, for which I am grateful.