Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

1 Smith, A. H., Later Greek and Roman Reliefs: Decorative and Architectural Sculpture, part 8, vol. 3 of Catalogue of Sculpture (London: British Museum, 1904) 231–32, no.2162.Google Scholar

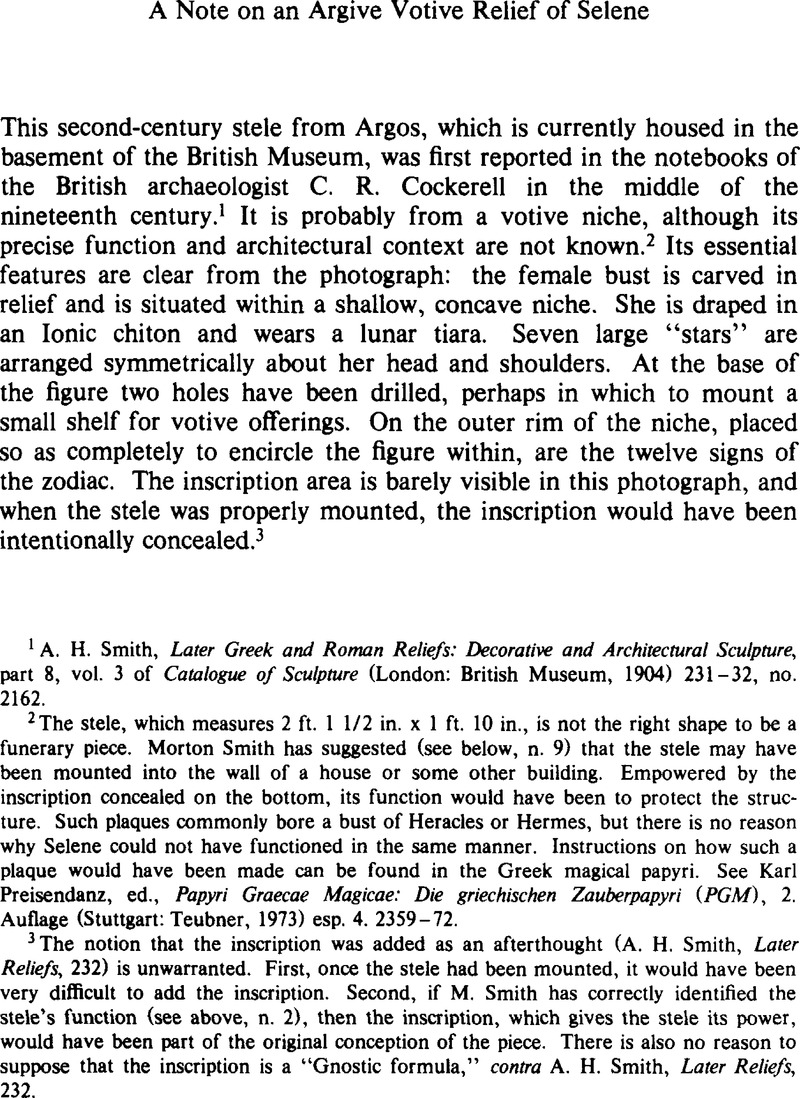

2 The stele, which measures 2 ft. 1 1/2 in. × 1 ft. 10 in., is not the right shape to be a funerary piece. Morton Smith has suggested (see below, n. 9) that the stele may have been mounted into the wall of a house or some other building. Empowered by the inscription concealed on the bottom, its function would have been to protect the structure. Such plaques commonly bore a bust of Heracles or Hermes, but there is no reason why Selene could not have functioned in the same manner. Instructions on how such a plaque would have been made can be found in the Greek magical papyri. See Preisendanz, Karl, ed., Papyri Graecae Magicae: Die griechischen Zauberpapyri (PGM), 2. Auflage (Stuttgart: Teubner, 1973) esp. 4. 2359–72.Google Scholar

3 The notion that the inscription was added as an afterthought (A. H. Smith, Later Reliefs, 232) is unwarranted. First, once the stele had been mounted, it would have been very difficult to add the inscription. Second, if M. Smith has correctly identified the stele's function (see above, n. 2), then the inscription, which gives the stele its power, would have been part of the original conception of the piece. There is also no reason to suppose that the inscription is a “Gnostic formula,” contra A. H. Smith, Later Reliefs, 232.

4 For the iconography of Selene, see Röscher, W. H., Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie (Leipzig: Teubner, 1890–1897) s.v. “Mondgöttin.”Google Scholar

5 On the rise of monotheism in antiquity, see MacMullen, Ramsay, Paganism in the Roman Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981) 83–94Google Scholar; on the expanding popularity of Isis, in particular, as a universal deity, see Helmut Koester, Introduction to the New Testament, vol. 1: History, Culture, and Religion of the Hellenistic Age (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982) 188–91. For the convergence of Hecate, Diana, Luna, Selene, etc., see Roscher, "Mondgottin," and see the Isis aretalogies in P.Oxy. XI. 1380 and Apuleius Metamorphoses 11.5.

6 A number of interesting examples of this motif are to be found in Joscelyn Godwin, Mystery Religions in the Ancient World (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981) 41 pi. 2; 45 pl. 8; 46 pi. 9; 83 pi. 50; 101 pi. 63; 103 pi. 65; 105 pi. 68; 106 pi. 69; 113 pi. 75; 149 pi. 115; 168 pl. 139; 171 pl. 142.

7 A rather well-known instance of this is found in the development of the Ephesian Artemis from a local city goddess to the universal mother of all in the later Roman period. See Robert Fleischer, Artemis von Ephesus und verwandte Kultstatuen aus Anatolien und Syrien (Leiden: Brill, 1973). Cf. pl. 12 with pl. 18: In the former, the older, local form, Artemis wears a simple necklace of grape clusters. In the latter, the later form, the goddess, now the universal mother, wears as her necklace the circle of the zodiac, which symbolizes her universal sovereignty.

8 Cf. Godwin, Mystery Religions, 42 pl. 3.

9 The inscription, which to my knowledge had not been previously deciphered, was explained for me by Morton Smith in a letter to Helmut Koester of 13 November 1982. The following analysis owes heavily to the expertise he has so generously shared.

10 So M. Smith (above, n. 9); see PGM 2. 128; 4. 2427; 6. 29; 7. 647–49; 9.3; 12. 3709; 13. 891.

11 So Smith; cf. PGM 4. 1266, where it is associated with Aphrodite.

12 See PGM 4. 2688–90: κάνθαρος τέλειος σεληνιακός.Cf. 12. 44, 4. 2457–58; and 3. 207.

13 So Smith (above, n. 9); see PGM 12. 289.

14 So Smith (above, n. 9); see PGM 5. 427, where it is one of several names written on a piece of paper, along with a diagram of the zodiac, to be rolled up and passed through the center of a “Hermes ring.” It apparently gives the ring its power.

15 See PGM 4. 1377, 1627; 5. 479, where a number of variations occur; Aβαωθ may be derived from a reduction of Σαβαωθ (cf. PGM 35. 28–29).

16 So Smith (above, n. 9).

17 The combination AB<A>ΩΘ-ΕΡΣΑΣ is further evidence for this rapprochement. A possible parallel to this phenomenon may perhaps be found in the second-century relief of Aion from Modena, the so-called “Modena Phanes Cosmocrator” (Godwin, Mystery Religions, 170–71). It is a male figure, encircled by the zodiac, with the rays of Helios streaming from behind his head, and the crescent of Selene resting on his shoulders. The present inscription reads “Felix Pater” but another inscription has been erased, which appears to have been a feminine name.

18 On the similarities to the Egyptian myth of Hathor (Isis), Osiris, Horus, and Set (Typhon), see Charles, R. H., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John (ICC; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1920) 1. 313.Google Scholar