In the summer of 1969, Earl Caldwell, an African American journalist working for the New York Times, visited a bookstore in one of San Francisco's black neighbourhoods. ‘“Times are changing”’, Jim Gray, the proprietor of the More Bookstore explained. ‘“Three years ago nobody around here would even steal a book. Now look, they buy books.”’ ‘Man, they're mad about this stuff’, Lewis Michaux, owner of the National Memorial African Bookstore in Harlem, New York, observed the following year. Amid the achievements of America's civil rights movement, and growing demands for black power, a ‘black revolution in books’ took place. Sales of works by and about African Americans soared, and publishing houses struggled to meet what historian August Meier, writing in 1969, called the country's ‘insatiable demand’ for studies of black history and culture.Footnote 1

The American media's absorption in the black freedom struggle, and the public's widespread interest in it and sibling movements, ensured that by the late 1960s ‘protest became saleable’. In this context, books on a number of causes, including feminism and environmentalism, found a sizeable readership among students, teachers, activists, and the wider public.Footnote 2 Scholars of radical print culture now recognize how print assisted groups, such as the Students for a Democratic Society, the period's so-called ‘writingest’ organization, with ‘recruiting, teaching, organizing, and radicalizing’.Footnote 3 Yet, in the United States at least, books written by, or for, activists also provided a way of funding social and political movements. The anti-war activist Abbie Hoffman donated money from his manifesto, Steal this book (1971), to a radio station in Hanoi, while several African American leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr, Malcolm X, and the poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, used royalties from literary works to fund their various projects. Although black political leaders, including the nineteenth-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass, had supported their activism in similar ways, only in the decade after the mid-1960s was this strain of activism, what the historian David Levering Lewis, writing about an earlier generation, termed ‘civil rights by copyright’, significantly enlarged.Footnote 4 Black power writers were among the most successful in the post-war US in turning print into profit.

Among the groups which most actively embraced book publishing as a source of funding was the Black Panther Party, which formed in Oakland, California, in the autumn of 1966. Between roughly 1968 and 1975, members of the Black Panther Party published some ten books, several of which became bestsellers and symbols of America's black power movement. These works provided an important source of revenue for the organization, generating around $250,000 from their advances. Between 1970 and 1971, book publishing raised $61,500 for the party, around one third of its total income during this period, and, by sustaining the national media profile of its leaders, also contributed a further $20,000 from related activities, such as campus talks.Footnote 5 These sums were comparable to what Grace Elizabeth Hale found for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which derived about a third of its operating costs in the mid-1960s from royalties on works like Howard Zinn's SNCC: the new abolitionists (1965), but substantially more than the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had earned in the mid-1960s from ‘books and booklets’. Such figures are also more than the SNCC Freedom Singers, or the musicians affiliated with the Panthers received from record sales, which constituted a ‘rather modest’ market.Footnote 6

Few accounts have made the financial underpinnings of the Black Panther Party's activism a point of close and sustained analysis, although a number have briefly noted how it raised funds by selling its newspaper, addressing student groups, securing grants from state agencies and donations from congregations, or holding benefit concerts.Footnote 7 The most recent scholarship on the Panthers has tended, at best, to gloss this subject, and the field continues to lack a broader understanding of what might be called the financial underpinnings of activism, examining how such groups raised, handled, and disbursed funds. Details of the party's finances are, for example, scattered throughout Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin's study, Black against empire (2013), among the most comprehensive surveys of the party, though such entries remain subsidiary to, rather than substantive of, their overall analysis.Footnote 8

The diffuse, abbreviated, and intermittent character of scholarship on the Panthers’ finances reflects the way in which scholars of post-war US social movements have handled this subject generally. As Peter Ling observed in a rare intervention on the topic, ‘very few studies deal directly with the funding of civil rights organizations’, a point one could apply to most accounts of second-wave feminism, anti-war activism, the gay rights movement, and nascent environmental organizing, as well as more recent studies extending the chronological boundaries of America's social movements.Footnote 9 Even when scholars have taken a greater interest in this subject, there still remains a need, as Wesley Hogan observes, to ‘integrate this more forcefully into our understanding of how [civil rights groups] functioned’.Footnote 10

This article aims to elevate the financial underpinnings of activism generally within the historiography of post-war social movements through a case study of the Black Panther Party. It suggests that historians must recover how activists raised funds, while also examining how they stewarded their resources, and in what ways money intersected with the demands of organizing and the tenets of ideology. By focusing on the Panthers’ efforts to generate income through the publication of books, the article also expands our conception of the sources from which US activists raised funds beyond the few accounts that have dealt with philanthropic foundations, or, more recently, congregations, the ‘primary source of funding’ for black power groups in the Midwest.Footnote 11

Raising money through writing books was a mode of fundraising that required diligent work and oversight and it therefore illuminates the wider administrative apparatus that the party fashioned. It shows how money was routed in ways far more intricate than was implied either by contemporary right-wing critics, who dismissed the party's commercial projects as providing ‘profits for Panthers’, or more recent scholars’ appraisals that such income directly paid ‘electric and gas bills, car rental costs, travel expenses, funeral expenses, bail funds and legal costs, rents and mortgages on properties’.Footnote 12 Books and bookkeeping were in fact entwined activities for the party, and this article uses their entanglement to reveal, for the first time, the collaborative nature of many of the Panthers’ literary projects.

The Panthers’ attraction to publishing lay broadly in a conviction that books could provide a powerful source of political communication, a means of countering the ‘distortions’ of ‘the mass media’.Footnote 13 Among black activists more generally, print culture was especially construed as an expression of political action, a stance famously expressed in Amiri Baraka's call for ‘poems that kill’, that ‘wrestle cops into alleys’. While the Panthers publicly opposed Baraka's brand of cultural nationalism, their programme was not entirely blanched of these sentiments, as Brian Ward has skilfully shown. Yet, as this article argues, the idea of print culture as political action was given a different inflection by members of the party, who regarded books as a ‘commodity’, and vital sources of revenue. The party's two founders, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, displayed this stance when they sold copies of Quotations from Chairman Mao (1966) to students at UC Berkeley for three times their cost, and used the profits ‘to buy two shotguns’.Footnote 14 Scholars of West German activism remind us that selling Mao's ‘Bible’ in such ways was widespread, funding Berlin's Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund and the Roter Stern bookstore in Marburg.Footnote 15 But Seale and Newton's action was distinct in that it was recounted in a bestselling book, Seize the time (1970), and thus doubly lined the party's coffers, as a reason for the book's popularity, sales of which contributed $20,000 towards Seale's legal bills.Footnote 16 Even Newton, who once dismissed the contribution books could make to organizing, in preference of ‘educat[ing] through action’, came to see that publishing could be a ‘tool’ of activism, and, like several within the organization, understood such literary projects within the ‘quotidian terms’ of fundraising, much as earlier civil rights groups did with music, offering ‘money with which to continue its work and the chance to publicize its efforts’.Footnote 17 It is a perspective that leads us to recognize how some of the books that US activists published were not only accounts, but examples of activism, and how by recovering the financing of such groups our grasp of the mechanics and possibilities of activism in these years is enriched.

I

The Black Panther Party's first sustained efforts at fundraising took shape in defence committees created to pay legal costs and to cover bail fees for the organization's most prominent members. The Huey P. Newton Defense Fund was among the first such committees, set up in Oakland, California, in November 1967 by Newton's mother and brother, his attorney Charles Garry, and the programme secretary of SNCC. The Fund sold thousands of buttons and posters, organized benefit concerts, formed alliances with California's Peace and Freedom Party, and oversaw scores of ‘Free Huey’ demonstrations. Within six months, it had raised $10,000. A similar event held in New York's East Village the following year for Eldridge Cleaver, the party's minister of information and a contributor to the San Francisco-based magazine Ramparts, drew support from civil rights and student groups, and raised $200,000. As well as generating funds, defence committees also acted as tributaries to recruitment, turning some, including Huey's brother, Melvin, from volunteers into members, a pattern replicated by campus groups and local chapters of the party.Footnote 18

Such committees also formalized the party's rudimentary fundraising structures, replicating a practice evident from earlier groups, such as the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King in the 1950s, which ‘laid the groundwork for a permanent and professional fundraising apparatus’ within the SCLC.Footnote 19 Upon joining the party in October 1968, Melvin Newton, Huey's brother, was made the Panthers’ first minister of finance, a role he held until the summer of 1969 when Patricia Hilliard, wife of the party's chief of staff, David Hilliard, became the first of several women to assume responsibility for party finances.

Even with these improvements, however, money continued to flow unpredictably, both in generosity and frequency. Furthermore, because most early appeals revolved around legal campaigns, it was also unclear how donations would be used. When a group of Episcopalian ministers mailed a cheque to Charles Garry in April 1968, they registered their ‘opposition to contributing to the Panthers if the money will be put into buying arms’.Footnote 20 While Garry dispelled the ministers’ concerns, other organizations, such as King's SCLC, handled such queries by offering in advance reassurances that fundraising was undertaken ‘in the most careful, economical fashion’.Footnote 21 That the ministers wrote to Garry showed the importance the Panthers’ lawyers played as conduits for the party's early donations, a relationship only marginally adjusted in later years.

As membership of the party grew, and as the organization spread from Oakland to the rest of California, and then across the US, it developed new sources of support. In a number of cities, as several scholars have shown, the party proved eager to fashion a left-wing inter-racial coalition, working with the Peace and Freedom Party, the Young Lords, Brown Berets, and United Farm Workers, in part because of the fundraising potential of such alliances.Footnote 22 The Southern Californian chapter of the Panthers that was set up in 1968, and became ‘the dominant presence in the Los Angeles Black Power scene’, relied greatly on the support advanced by the LA Friends of the Panthers, which listed Marlon Brando and the Columbia Pictures producer Bert Schneider, as well as the writer Donald Freed, among its supporters. It was a pattern that, to some extent, continued the assistance that actor Harry Belafonte and other Hollywood figures had provided for King's SCLC in the mid-1960s, and it defined the pattern of collaboration more generally between local branches of the party and their white sympathizers, as evidenced by the formation of the National Committee to Combat Fascism in Boston, and the White Panthers in Detroit and Ann Arbor, Michigan.Footnote 23

Those involved in the cultural industries were also conspicuous among early supporters of the Panthers, a fact that explains the diversity of gifts the party received, and its ascendant media profile.Footnote 24 Editors and publishers, including Robert Silver, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Warren Hinckle, and Gloria Steinem, lent their names to the International Committee to Defend Eldridge Cleaver, in 1968, while Random House editor John J. Simon held fundraisers and offered book contracts. Random House was especially keen to work with the party, burnishing its credentials as the promoter of fresh voices of political import by adding accounts from the party's leading figures to a list that already included works by activist Stokely Carmichael, the ‘first’ anthology of women's writing, and a sympathetic study of the United Farm Workers. Crucial to these early relationships was Cleaver, whose grasp of the commercial potential of the party's image, and the opportunities presented by publishing, stood in contrast to many activists’ ‘antipathy for text’, and outlines a stance that challenges dismissals of him as a doctrinaire opponent of the uses of black culture.Footnote 25 It reminds us that the division between revolutionary and cultural nationalism was not the only frame within which the political value of black culture was weighed.Footnote 26

It was Cleaver's ascendant literary profile that led the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, to begin following the trail of money from ‘Leonard Bernstein and Peter Duchin and that crowd’.Footnote 27 The ‘artistic crowd’ that Hoover identified as a major source of the party's income came to national attention in January 1970, following a party at the New York apartment of the conductor Leonard Bernstein and his wife Felicia, which the writer Tom Wolfe brutally satirized some months later. The Bernstein soiree was organized by the Committee to Defend the Panthers in an attempt to raise money for twenty-one New York Panthers arrested in April 1969, and charged with attempting to blow up several of the city's institutions. The Committee was started by a group of old leftists from the world of film, though increasingly it comprised a ‘very loose arrangement’ of New York-based supporters, including the peace activist David Dellinger, the Harlem community organizer Marie Runyon, and Martin Kenner, a stalwart of student and anti-war groups. Kenner's lawyer Gerald Lefcourt, who was defending him on charges stemming from the 1968 strike at Columbia University, had introduced him to the Panthers, and he swiftly established himself as one of the party's most talented organizers.Footnote 28

Unlike earlier groups of supporters, the Committee to Defend the Panthers served as ‘a nation-wide defense and bail fund for the Panthers’.Footnote 29 With offices in New York, New Haven, and Boston, the Committee organized fundraising events, film screenings, demonstrations, and courthouse publicity events around the east coast. Throughout 1970, it also printed scores of pamphlets, fact sheets, press releases, and trial bulletins, offering alternative accounts to mainstream news bureaus. Cheaply produced and mimeographed, such handbills were examples of what John McMillan has called the period's ‘democratic print culture’, and, much like the photographs taken by civil rights activists, they helped activists regain ‘control of [their] public image’, while providing opportunities to appeal for donations.Footnote 30 Sometimes these documents were gathered into anthologies, the genre favoured by the period's social movements, and which, as the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis proved with If they come in the morning (1971), could ‘reach tens of thousands of people’ and earn ‘a substantial advance’ from its publisher.Footnote 31 As the co-editor of Fidel Castro speaks (1969), one of several ‘handbooks for revolutionaries’ produced by Grove Press, Kenner knew that such texts spoke ‘to the youth of America’, while providing a direct source of income for activists.Footnote 32

Amid the pressures of rising bail fees and trial costs, the party's rudimentary fundraising infrastructure grew rapidly. Kenner brought his cousin, Bette Shertzer, onto the Committee, and asked Victor Rabinowitz, the president of the left-wing National Lawyers Guild, to draw up a charter. Rabinowitz and his law partners also alerted the Committee to a loophole by which they could pay bail fees using state bonds, a strategy that saved the Panthers tens of thousands of dollars because bonds with equivalent value were ‘selling at a deep discount’.Footnote 33 When bail was set at $30,000 for David Hilliard, the Committee paid with $20,000 worth of California State bonds, and covered Newton's $50,000 bail fees with bonds bought for $29,000.Footnote 34 All told, the Committee covered $155,000 in bail fees with low coupon bonds bought for a third of the cost, while retaining the income on their investment.Footnote 35

The party's deft use of these strategies demonstrates, as the historian Devin Fergus found in his study of the organization in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, that the party relied greatly on ‘experts friendly to Panther claims’ to furnish them with technical advice and assistance.Footnote 36 In the case of the party's fundraising efforts, many of the figures, such as Rabinowitz and Kenner, who assumed responsibility for the party's commercial assets, were white, often Jewish, and thus unable to join the party even if they had wished to do so. Such supporters also tended to be older than the average rank-and-file activist, a demographic trait some scholars have also noticed within the European New Left.

The strategy pursued by the Committee to Defend the Panthers was strained by the publication of Wolfe's essay ‘Radical chic’, in June 1970, which magnified the sense that the party depended on the generosity of ‘a Leonard Bernstein or a Bert Schneider’, and therefore meant it could be ‘pilloried as really just radical chic’.Footnote 37 Stories of its indebtedness to such figures became a staple of right-wing periodicals, which regularly printed stories of its intention ‘to make a lot of honest loot by talking up revolution’.Footnote 38 Such perceptions, combined with Newton's release from prison, and the formation of the Cleaver-led International Panthers in Algeria, prompted some within the organization to contemplate alternative ways of overseeing their finances. Kenner arranged a meeting at the New York offices of lawyer David Lubell, another member of the National Lawyers Guild, inviting Newton, Hilliard, and Ramparts editor Robert Scheer, and the five men agreed to incorporate an entity that would exist ‘separate and apart from the Black Panther Party’ for this purpose.Footnote 39 These shifts in how the party proposed to steward its money also arose from hardening internal divisions, and underscored how questions of fundraising and administration were inseparable from those of ideology.

II

Stronghold Consolidated Productions was incorporated under New York State law on 22 September 1970, and took control of the party's assets, and, to a degree, its affairs. By existing apart from the party, it provided ‘an efficient and centralized entity for the receipt of all the income’ generated by book deals, television appearances, campus talks, films, and similar activities.Footnote 40 As several disaffected members of the party later observed, the agency's formation marked the culmination of ‘the centralization that Huey started’ following his release from prison.Footnote 41 Indeed, the formation of Stronghold, and the modes of fundraising it enabled, was crucially connected to the party's reorganization and its ideological repositioning.

Following Newton's release from prison, and the growth of the party to an estimated sixty-eight branches, Stronghold brought a measure of cohesion to the party's financial arrangements. While money continued to be routed through the party's lawyers, its passage was now formalized by contracts, not custom. Administrative files for the Committee to Defend the Panthers were passed to Lubell, and party members aspiring to write a book or cut a record were presented with a contract that assigned rights and royalties to Stronghold.Footnote 42 Oakland activists were also added to the party's main New York fundraising group, and an agreement was signed to ensure that monies raised by it were passed to Stronghold.Footnote 43 All of these changes happened as relations between the Oakland and New York Panthers became more fractious, and indeed abetted what Lubell later called ‘the party[‘s] reorganization’.Footnote 44

The creation of the Cleaver-led International Black Panther Party, also in September 1970, made urgent the question as to where streams of revenue would flow within the party. As tensions escalated between all three factions – in Oakland, New York, and Algeria – supporters were forced to pick sides. A San Francisco-based film production group, American Documentary Films, allied itself with the International Panthers, sending copies of films to Algeria while deducting processing costs from the Oakland account.Footnote 45 The same pattern also emerged around the party's most valuable asset, its newspaper, though Stronghold was more successful in retaining those funds.

Since adopting a weekly schedule, in April 1969, The Black Panther newspaper had been the party's most lucrative source of revenue. According to government investigators, by mid-1970 the newspaper was providing ‘a fairly consistent and substantial profit’, generating around $5,000 per week for the Oakland group, though much less for local branches.Footnote 46 It was not surprising therefore that Lubell ensured such funds flowed to Stronghold, reorganizing the relationship between the party and the paper so that while Stronghold paid for the paper's production, all subscription fees, ‘regardless of whether such monies are more or less than the cost of printing, publication and distribution’, would be funnelled directly back to it, accompanied by receipts.Footnote 47

Within weeks of this agreement, Lubell had also reduced the cost of producing the newspaper by moving production to Queens and printing to Brooklyn. These decisions allowed Newton to send two of his trusted advisers to watch over the dissident New York branch, and thus showed how financial decisions began to reshape the party's operation. Within weeks of them taking effect, two of the New York Panthers, Richard Moore and Michael Tabor, along with Tabor's new wife, Connie Matthews, disappeared, with Tabor forfeiting $150,000 in bail money, and, because this had been guaranteed with bonds, damaging relations with several of the party's backers. When the pair resurfaced in Algeria some weeks later, the Oakland Panthers denounced them for their ‘treacherous acts’, and told supporters they had ‘defected from the Black Panther Party’.Footnote 48

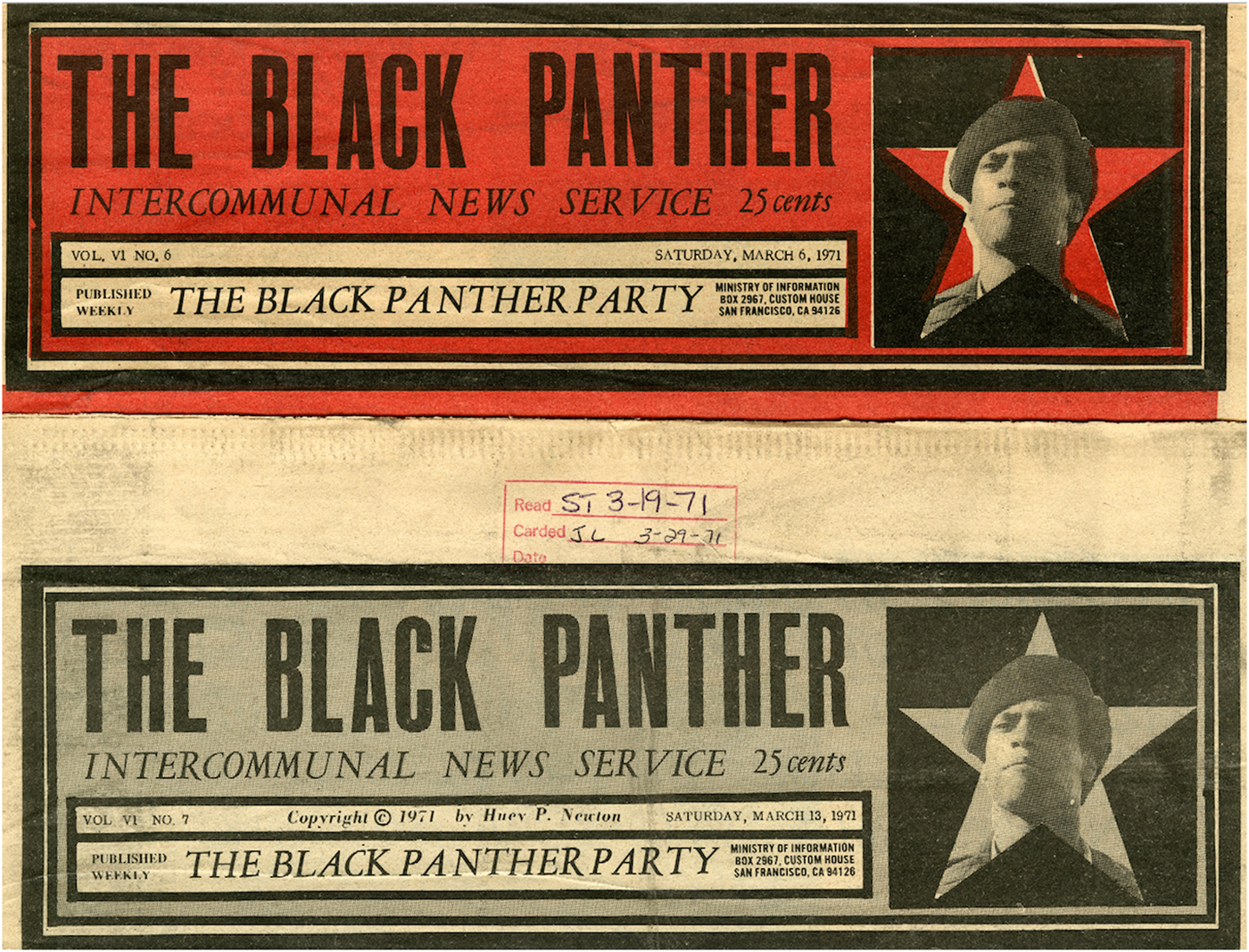

The expulsion of the International Black Panthers and the New York Panthers was announced in the party's newspaper on 20 March 1971. The verdict appeared on the front page of the newly titled Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, underneath a redesigned masthead that claimed the paper was copyrighted by Huey P. Newton (see Figure 1).Footnote 49 The New York-based Panthers responded by dismissing it as a ‘Black Capitalist Rag Sheet’, and printing an alternative, Right On! Black Community News Service, in which they exposed how party funds were used ‘to finance the lavish tipping of Huey P. Newton…and David Hilliard’.Footnote 50 It was not just the “‘centralization’” or even “‘misappropriation’” of funds that the New York Panthers objected to, but rather the way in which an “‘obsession with fund raising’” had replaced revolutionary organizing within the party.Footnote 51 The party's internal factionalism arose not only out of ideological and tactical differences then, but also the new legal and financial structures it had created.

Fig. 1. Mastheads of The Black Panther newspaper, from 6 and 13 March 1971, showing the first issue that claimed copyright. Image courtesy of Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

While Cleaver, Tabor, and other members of the New York Panthers identified Newton and Hilliard as the main architects of these new financial arrangements, they overlooked, as many scholars have done, the role that the party's advisers played in fashioning these moorings. Yet by early 1971, Kenner was regarded as the party's ‘skilled financier’, helping Stronghold to generate more than $200,000 from its newspaper, book contracts, and lecture fees, and turn a net profit of $94,400 in its first year.Footnote 52 Lubell supported these efforts by finding new ways of harvesting an income from the party's existing cultural assets, charging those who wished to reprint the party's ‘Ten Point Program’ and, recognizing the ‘immense visual cachet’ of Emory Douglas's artwork, stamping existing print runs with a Stronghold copyright insignia.Footnote 53 Some of the money raised from these ventures was invested in bonds through a minority-led Wall Street investment firm, though most was used to purchase properties, or pay existing mortgages.Footnote 54 By 1972, Stronghold held some ten properties, worth $255,000, which ensured the party's presence in Oakland, Berkeley, Chicago, and New Haven.Footnote 55

One of the properties in Stronghold's rental portfolio was a spacious apartment next to Lake Merritt in downtown Oakland. The property was intended as Newton's base, though the lease noted that ‘writers under contract with the corporation’ might also use it.Footnote 56 In subsequent years, the apartment hosted editors and functioned as a writing studio for a number of the party's literary projects. Indeed, the property was closely tied to the publishing and fundraising strategy overseen by Stronghold. The acquisition of such apartments was made possible by Bert Schneider, the early supporter of the LA chapter, who made several loans to the party, including one which provided the funds to establish the Oakland Community Learning Center, the basis for the party's later school. Although the scale of Schneider's generosity was unmatched, the party's acquisition of property through white ‘front buyers’ was commonplace, and was a practice widely employed by its Bay Area realtor Arlene Slaughter.Footnote 57

Such arrangements were replicated in New York, where Shertzer and her friend Judy West, a labour activist, secured a $25,000 loan from Chase Bank to buy a store, which they opened in 1973 as Seize the Time Books and Records. Shertzer and West had supported the party since joining the Committee to Defend the Panthers, and they opened their store to ‘provide…some needed funds’ for the party, sharing proceeds and hosting fundraising events.Footnote 58 Their hope that the store would ‘demonstrate what our ideology is’ was of a piece with other exercises in neighbourhood empowerment, and resembled what many ‘activist entrepreneurs’ said about their businesses.Footnote 59

If the party's willingness to accept the help of these supporters appears at odds with its leaders’ calls for the radical restructuring of society, it was nevertheless consonant with the attachment it, and other black power groups, displayed towards programmes of economic empowerment.Footnote 60 It also aligned with the party's embrace of socially conscious capitalism, as this position was advanced in two brief statements, both entitled ‘Black capitalism re-analyzed’, which conveyed its support for ‘“businesses that support our community”’.Footnote 61 Both documents were printed in The Black Panther newspaper in June and August 1971, and, despite implying Newton's authorship, were likely composed several months earlier by one of Stronghold's amanuenses.Footnote 62 If they suggested a ‘new approach’ to black capitalism such a reorientation cannot straightforwardly be attributed to Stronghold's creation, though the agency's management of the party's finances did make local chapters more reliant on donations from neighbourhood businesses to support their welfare programmes.Footnote 63

These economic circumstances ensured that in their negotiations with publishers, Kenner and Lubell pressed editors for ‘a large initial advance’ rather than haggle over royalties.Footnote 64 It also explains why they were drawn to trade presses, in consequence of their ability to offer magnificent sums, and Stronghold's agents placed their proposals with major US publishers: W. W. Norton; Doubleday; Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich; and, especially, Random House. At a moment when selecting a publisher was intensely scrutinized, especially among African American critics, the Panthers’ resolve to work with these presses sent out a clearer signal than those its musicians made to release their records on commercial labels. Theirs was a decision made in the belief that the principal audience for these books would be ‘the predominantly white counterculture’, a constituency Grove Press also targeted when it reissued Frantz Fanon's work, and that was widely identified as readers of black power texts.Footnote 65

Among the expanded market that Stronghold contemplated through its literary projects were members of the European New Left, who were otherwise reliant on the erratic distribution of the party's newspaper, and occasional student exchanges. European supporters imagined that translations of the party's core documents would provide ‘a tool for…international awareness’, and left-wing publishers, such as the German Bernward Vesper assembled several non-commercial pamphlets, similar to those that circulated on US campuses. These were often done independent of the party, replicating the manner in which many of its international cells had emerged, ‘outside the official auspices of the US Panthers’, and such publications largely raised money not through royalties but by appeals for donations.Footnote 66

By contrast, Stronghold's agents concentrated on the sale of foreign language rights, a task that forced them to weigh the political allegiances of presses with the generosity of their advances. This was a problem of the moment, and many black writers had to weigh ‘the dollars and cents of it, and/or the publisher's capability of reaching an audience’, as the poet Nikki Giovanni explained in 1972.Footnote 67 The Panthers usually solved this equation by allowing the support expressed by, for example, the small left-wing French press Gallimard to outweigh the larger advances offered by Flammarion or Laffont.Footnote 68 They did so because, as Kenner recognized, selling rights to an enthusiastic foreign press might ensure a title ‘builds steam’, generating excitement, and making ‘the book attractive to a paperback house’ in the US, where the greatest financial reward lay.Footnote 69 The Oakland-based Panthers’ determination to publish their work with US commercial presses, or an enthusiastic foreign one, underlines the primacy of financial motivations in these projects.Footnote 70

Revenue from publishers and cultural agencies increased notably for the Oakland Panthers after August 1970, though such sums continued to be supplemented by the generosity of wealthy donors. To solicit such donations, the party held book launches, and mailed inscribed copies of their works to those they thought of influence or of means, some identified from a list of ‘names of some big contributors’ who had once given to the earlier Committee to Defend the Panthers.Footnote 71 Raising money in this way was crucial to how the party supported itself between 1970 and 1973, publishing not only bringing in advances and royalties, but enmeshed in a dense web of activity.

III

Publishing, and especially the production of books, penetrated deeply into the financial and administrative structures of the Oakland-based Panthers by the early 1970s. Funds generated through the sale of books allowed the party to develop other commercial assets, not least its portfolio of property holdings. As Kenner later explained, ‘the money went from the literary things into buying property’.Footnote 72 Publishers’ advances served amply as deposits on inner-city houses, but Kenner saw how publishing might also lessen the costs of owning those buildings. Because several properties were used by the party's amanuenses, the costs involved in housing those figures could be recorded on Stronghold's accounts as ‘business expenses’, and thus subtracted from the agency's tax bill. When party funds ran low, book contracts could reassure hesitant creditors, and parry the questions of reporters.Footnote 73 The financial underpinnings of the Black Panther Party cannot be understood without reference to this programme of activity.

Money earned from book deals was described in Stronghold's accounts as its ‘literary property’, with existing ‘assets’ distinguished from ‘possible future sources of income’.Footnote 74 While Lubell kept watch on these columns, Kenner was attentive to the pace at which a work moved across them. He drafted charts to manage the production of literary projects, and related these to his economic forecasts.Footnote 75 In good times, the pair believed that ‘a fairly immediate source of possible money is the books we are developing’, and in bad times they believed little else. When the party became ‘caught in a serious short term money squeeze’, as happened in mid-1972, with debts exceeding $20,000, Kenner's ‘expectation of repayment’ lay with ‘an advance on a second book of letters of George Jackson; a record contract for Elaine [Brown]…[a] contract on Hidden Traitor; a contract on Ericka [Huggins's poetry collection] Fire and Rain’.Footnote 76

These arrangements relied on the development of new projects, a task that fell to Kenner. His first proposal, entitled Hidden traitor, was a work that would describe Newton's relationship with Cleaver, and ‘identify the reasons for the failure of contemporary revolutionaries’; the second would be a sequel to Seize the time, updating Bobby Seale's life, ‘From Chicago to Attica’. Random House staff worried that the first project would be too ‘blatantly a hatchet job’, but gambled on its success, and gave a $5,000 advance.Footnote 77 The Seale project had languished since 1970, and was only revived by financial necessity. When a manuscript was finally submitted to Random House in 1972, its editor, John Simon, found the work to be ‘rambling’, and ‘without focus and cohesion’. He told Lubell the problem arose because the work did not have ‘Art Goldberg assuming total responsibility for the shape of the book’, referring to the Ramparts writer, who had transformed ‘a collection of barely edited conversations’ into a captivating narrative. Experienced writers to whom the party had long turned were crucial to the success of its literary projects, having ‘shown from past experience [their] ability to work well and fast…on oral books’.Footnote 78

‘Oral books’ were those that began as interviews before being moulded into a narrative by a seasoned writer, and they were a staple of the party's literary corpus. Few reviewers, and fewer scholars, seem to have noticed the team of scribes who produced these works for the party, perhaps because completed texts did not dwell on the matter, though such neglect is widely encountered in studies of African American literature.Footnote 79 It was this model of production that accounted for two of the period's most influential works, Malcolm X's Autobiography (1965), and Robert F. Williams's Negroes with guns (1962), as well as Californian journalist Jacques Levy's ‘autobiography’ of César Chávez, and it is hardly surprising that scores of the Panthers’ books were composed in similar ways. Even Cleaver's manuscripts, which might be thought to lie to one side of such arrangements, involved mild acts of collaboration, with his lawyer, Beverly Axelrod, editing Soul on ice (1968) ‘to exaggerate the violence of Cleaver's writing persona’.Footnote 80

Seize the time was a lucrative work, selling more than 90,000 copies in the eighteen months after its publication. It cost the party $500 to produce, most spent on typists, a researcher, and subscriptions to several countercultural periodicals. These were the materials that Goldberg, a former leader in Berkeley's Free Speech Movement and an erstwhile journalist, needed to turn two years of stray interviews with Seale into a narrative. Random House did not deny Goldberg's involvement in the project, admitting only that he had been ‘responsible for the editing of the transcribed tapes’.Footnote 81 His contribution indicated that the party's ability to produce such works relied on the ‘Bay Area's interlocking countercultural circles’, and especially those encompassing the University of California–Berkeley.Footnote 82 While some articles in the Panthers’ newspaper drew on reports from the institution's Survey Research Center, Berkeley faculty, especially in the department of sociology, were crucial to the party's book projects. The sinologist Franz Schurmann wrote an introduction for To die for the people (1972), and J. Herman Blake, a doctoral candidate, drafted around a third of that anthology's essays, though they appeared under Newton's name.Footnote 83

Similar patterns of support were crucial in the production of works such as the collective autobiography of the New York Panthers, Look for me in the whirlwind (1971), which its editor described as a ‘talked rather than a written book’, and Revolutionary suicide (1973). Both works began with interviews transcribed by female stenographers, and so continued a pattern evident since the party's formation whereby unacknowledged women turned its leaders’ ideas into written texts.Footnote 84 In November 1971, Gwen Fontaine, Newton's then girlfriend, billed Stronghold for $2,000 for ‘the typing of the George Jackson manuscript’, a handsome sum, and one that requires an explanation.Footnote 85

Who paid the party's writers and typists, and what work those payments covered, were not straightforward matters, because they touched on the relationship between the party and Stronghold, and the latter's bookkeeping practices. Some of the writers who assisted the party certainly believed that the income generated by their efforts paid for the party's ‘other survival programs’, and at least one recent scholar has repeated the claim, though in fact matters were more complicated.Footnote 86 Lubell regularly used Stronghold's money to reimburse the east-coast supporters who housed activists during their speaking tours, but he ensured that donations from those events did not flow into Stronghold's coffers, for such would ‘present…technical problems’.Footnote 87 Those problems arose from the fact Stronghold was a corporation, paying tax of ‘nearly 50 cents on every dollar’, including on income not ‘related to how the corporation gets its money’. While certain expenses, such as the cost of printing the party's newspaper, were ‘important in keeping down the taxes’, being subtracted from profits, other costs, like a phone bill from the Panthers’ shoe factory, could not be offset.Footnote 88 ‘Billing party functions to Stronghold’, Kenner warned, was ‘the beginning of a bad practice’, and he outlined a strategy by which unrelated expenses could be funded by Stronghold: ‘Any money that is cashed by me…and not backed up by receipts for legitimate expenses is taxed by government at the rate of 50%…Money to a typist for typing book manuscripts is a legitimate expense and is deducted from our profits for the year.’Footnote 89 It was in this context that Fontaine received $2,000, ostensibly for the typing of the Jackson manuscript, and that comparable sums were disbursed to other members. Typing and editing were legitimate, and easily fabricated, expenses for Stronghold, while also providing a means of transferring funds to Oakland.

In late 1972, Kenner deepened these financial grooves. ‘If the party wants Stronghold to pay certain bills that are not “legitimate”’, he told Fontaine, ‘for taxes purposes I would prefer funnelling that money through people whom we can call legitimate’.Footnote 90 Within a couple of months, Stronghold was providing five members of the party with a $5,000 ‘salary’ for working on its book projects. In turn, these members paid rent to Stronghold for accommodation, allowing the agency to list those buildings as ‘a business expense’, and to deduct interest on mortgages, property taxes, and structural depreciation.Footnote 91 Though civil rights groups, including the SCLC, also took advice from advisers to lessen their tax burden, the Panthers played the capitalist game with immense skill.Footnote 92

While these practices were effective in offsetting Stronghold's tax liability, because they tend to conceal if payments were genuine or strategic, they are equally successful in confounding those who wish to illuminate the Panthers’ reliance on sympathetic writers. While a number of Stronghold's invoices constitute evidence of how money was routed within that organization, closer inspection of the production of one of the party's books, Revolutionary suicide, places beyond doubt the collaborative nature of its literary projects, and their interconnectedness to the party's financial arrangements.

Revolutionary suicide is usually classified as Newton's autobiography, though its title page records that it was written ‘with the assistance of J. Herman Blake’, and Blake has since spoken about his ‘weekly tutorial’ with Newton.Footnote 93 As an occasional presence around the Black House, the ‘headquarters’ of San Francisco's black arts movement, Blake knew several members of the party, and, while never a member of the organization, assisted with its literary projects (see Figure 2).Footnote 94 In June 1970, he and Newton signed a contract with a publisher, agreeing to co-author a book and to split the advance, a deal Stronghold inherited five months later. Following the book's publication, though, these arrangements became the basis of a dispute, and then a court case.

Fig. 2. J. Herman Blake and Huey P. Newton, Oakland, California, c. 1972, Photograph by Ducho Dennis. Reprinted with permission of It's About Time: Black Panther Party Legacy and Alumni/ Sacramento, California.

In the case he brought against Stronghold, Blake charged that the agency had failed to honour its agreement, leaving him ‘to beg…for what I should be able to expect with dignity’. He swore under oath that he was the book's ‘principal author’, furnished ‘tapes of most of my interviews’, rough drafts written in his hand, and ‘the original manuscript submitted to the publisher’.Footnote 95 Receipts showed that he had frequently interviewed Newton and his family, and had paid two of his students to type up this material.Footnote 96 Still, Stronghold countered that when Blake shared his manuscript, it seemed inadequate, requiring ‘additional work’, with Freed and Melvin Newton having to assist with ‘the writing and editing of Huey's tapes’.Footnote 97 Had the court requested an opinion from the book's editor, he would likely have confirmed the involvement of those men, and added that Kenner had also contributed, and that the work's copy-editor had written ‘a chapter that tied Eldridge into the theme’.Footnote 98 The only one never mentioned as having written any part of the work was Newton.

If the parties disputed how much work Blake did on the manuscript, or how much he should be paid, no one doubted that the book was a collaborative project. In June 1976, Stronghold was ordered to pay Blake $8,250, though by that point the agency was ‘defunct with no assets’. While Blake tried to recoup these monies by filing against the ‘various parcels of property’ he knew Stronghold to have held, the complexity of those arrangements, coupled with the party's disarray, ensured his efforts, and those of other creditors, came to naught.Footnote 99 While Stronghold disappeared, Newton, the agency's ‘sole shareholder’, continued to follow many of the commercial practices that the agency had devised, adding copyright insignia to his graduate school essays, and negotiating to turn his doctoral thesis into a book by working in collaboration with a known ‘co-author’.Footnote 100 It was a final instance of how the party's literary projects shaped both the party's finances and the socialization of some members, doing so in ways not dissimilar to how Kathleen Cleaver characterized the influence lurid media coverage had on ‘the imaginations of young blacks’, encouraging them to ‘see themselves as television portrayed them—as revolutionaries’.Footnote 101 The cluster of texts published by party members in these years documented the party's activism, but they also, through the manner of their production, and the way in which they stabilized a repertoire of administrative and commercial practices, profoundly shaped the culture of the party's organizing.

IV

The funding strategy that had sustained the Panthers since the late 1960s unravelled in 1973. Lubell stopped representing Stronghold and, by the end of that year, Kenner also distanced himself from the party. They were not the only ones to leave the party, as general membership declined. Although it is tempting to ascribe the party's demise in these years to what historian Peniel Joseph has called the shift in Newton's character, from ‘revolutionary’ to ‘racketeer’, it should be clear that the downturn in the party's literary assets played a crucial role.Footnote 102 As sales of the party's books plummeted, and negotiations around future ones faltered, the Panthers’ income from these sources, and indeed that of other black writers, rapidly diminished. Several of the party's members now resorted to ‘the twilight world of Oakland's after-hours clubs and vice industry’ to pay bills, as Donna Murch has argued.Footnote 103

As one of the major beneficiaries of the black revolution in books of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Black Panther Party's finances were badly dented by what political scientist Jerry Watts termed the declining ‘efficacy of the black militant appeal’.Footnote 104 While other black writers, such as Julius Lester, Toni Cade Bambara, and Amiri Baraka also noticed this shift in literary taste, alongside the related decline of the alternative press, and the closure of black studies departments, because the Panthers had been so reliant upon this infrastructure to produce and sell their works, their finances suffered greatly, and the moment provoked a further recomposition of the organization.Footnote 105 Still, the party was not alone among black power groups in experiencing this demise in funding. Black power groups in Illinois that had received funding from church congregations also noticed a ‘precipitous decline’ in those contributions, as church executives withdrew their support in response to external pressures.Footnote 106 The financial underpinnings of black power activism therefore had a distinct chronology and contour, and only as scholars recover this aspect of post-war social movements will it be possible to explain fully the historical prospects and possibilities that particular groups of activists faced. As one former Panther observed, ‘“in order to keep the movement going, you've got to have capital”’.Footnote 107

The approach developed in this article has also related the changing administrative structures that the Panthers developed to steward their financial resources to the party's reorganization around 1970. Examining the Panthers’ finances affords scholars, at a secondary level, the opportunity to identify more precisely the forms of support that the party, and indeed other groups, received from supporters. In the case of the Panthers, such assistance included technical and legal advice, such as paying bail fees with bonds, as well as help in turning interviews into publishable narratives, and it was provided by supporters, many absent from previous accounts, who were older than the party's rank-and-file.

If a black publication explosion in the late 1960s created funding possibilities for the Black Panther Party, and other activists, a buoyant market in African American historical artefacts in the late twentieth century did likewise for the sale of a large collection of documents, described as the party's archive, to Stanford University, the region's wealthiest academic institution. The archive was sold by the Dr Huey P. Newton Foundation, a non-profit corporation set up in 1993, to ‘develop educational materials and things relating to the socio-political theories, ideals and history of Huey P. Newton’, following Newton's murder in August 1989. Functioning as ‘the legal caretaker, or owner, of the materials Huey left behind’, the Foundation claimed copyright over his past works, submitted trademark applications, and launched a range of merchandise.Footnote 108 These developments took place at a moment when a resurgent black nationalism embraced the Panthers, along with Malcolm X, as historical icons, contributing to a renewed interest in books by former members, the reissuing of works such as Carmichael's Black power: the politics of liberation, and to the wider ‘commodification of 1960s radicalism’.Footnote 109 Nevertheless, while Stanford's acquisition of the party's archive made it possible for scholars to start examining the group's history, proceeds from that sale, estimated at around $1 million, assisted the Foundation in its work in the Bay Area, using ‘some of the revenue to educate’.Footnote 110 It is a reminder that if books produced by members of the Panthers, and other groups, in the late 1960s and early 1970s modified conceptions of political action, being examples as much as accounts of activism through the money they generated, we should not overlook how, in recent decades, sales of historical documents have assumed a similar role for these activists and their custodians.