The following Communication presents a newly discovered manuscript by John Locke. The manuscript dates from 1667–8 and it deserves notice as the most significant example of Locke's thought on the toleration of Catholics prior to the Epistola de tolerantia (1689). In recent decades, scholarly work on Locke's intellectual development has devoted particular attention to his stance on the toleration of Catholics.Footnote 1 Locke's response to Henry Stubbe's Essay in defence of the good old cause (1659) is often described as the earliest evidence of his attitude on the issue, before his ‘Discourse on infallibility’ (1661), his enlightening visit to Cleves (1665–6), and his Essay concerning toleration (1667–8).Footnote 2 According to this narrative, Locke's position would evolve to tolerate every religious sect on the basis of their speculative beliefs and worship, but consistently except Catholics for their seditious articles of faith: the pope's power to dissolve oaths, to legislate infallibly, and to depose foreign rulers as excommunicates or heretics. The manuscript below reveals that Locke reached this position only after he had addressed a number of arguments in favour of Catholic toleration. In the first two sections of the article, we describe the provenance, content, and context of the manuscript, and examine how it influenced, and possibly inspired, the Essay concerning toleration. In the third section, we transcribe the manuscript itself.

I

In May 1667, Locke entered the household of Anthony Ashley Cooper (1621–83), Lord Ashley, against a backdrop of political turmoil.Footnote 3 Within a month, the Dutch Raid on the Medway (19–24 June) would corrode popular support for Charles II, prompting the fall of Edward Hyde (1609–74), the first earl of Clarendon, and emboldening nonconformists and their allies to push for a new church settlement. Persecutions conducted under the Act of Uniformity (1662), the Conventicle Act (1664), and the Five Mile Act (1665) had, since the Restoration, alienated nonconformists, whose support was now required to buttress the crown. The final months of 1667 and the first of 1668 witnessed an outpouring of works on the question of the ‘comprehension’ or ‘indulgence’ of nonconformity: the issue of whether the Church of England would ‘comprehend’ Protestant dissenters within its ranks or ‘indulge’ their worship outside of the church. Between August 1667 and 9 May 1668, when parliament was adjourned, at least twenty-three pamphlets appeared on the question.Footnote 4 It was during this time that Locke wrote, but did not publish, the earliest versions of his Essay concerning toleration. The Essay was an extended defence of religious toleration which remained in manuscript until 1829, when Locke's biographer and relative Peter King (1776–1833) printed extracts from one of its versions; it later appeared, at greater length, in H. R. Fox Bourne's Life of John Locke (1876),Footnote 5 but no serious attempt to edit the Essay or examine its context was made until J. R. and Philip Milton's Clarendon edition of 2006.Footnote 6 In the Introduction to their edition of the Essay, the Miltons provided a comprehensive overview of the debate entrained by the fall of Clarendon, but could find no direct connection between its publications and Locke's work. They did, however, note the similarity between Locke's arguments and those presented in two anonymously published pamphlets, attributable to Sir Charles Wolseley (1629/30–1714): Liberty of conscience…asserted & vindicated (1668) and Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest (1668). Wolseley, the Miltons maintained, was an author ‘who probably came closest to Locke in his general outlook’ on toleration,Footnote 7 yet they could find no evidence of Locke's knowledge of Wolseley's publications. The manuscript which we present below confirms the Miltons’ suspicions. Roughly 3,000 words in length and entitled Reasons for tolerateing Papists equally with others, the manuscript draws directly upon Wolseley's Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest, and constitutes the earliest extant draft of passages in the Essay concerning toleration.

The manuscript is conserved in the Greenfield Library of St John's College, Annapolis. It is a gathering of two folded half-sheets (212 mm × 159 mm), making four leaves or eight pages in total: fos. 1v, 3v, and 4r are blank; fos. 1r, 2r, 2v, and 3r bear text in Locke's hand; and 4v bears his endorsement ‘Toleration. 67’.Footnote 8 The manuscript is wrapped in another folded half-sheet, addressed ‘For Edward Clark of Chipley Esqr’ – Locke's friend, Edward Clarke (1650–1710), the MP for Taunton (1690–1710) – with an additional endorsement (‘Mr. Locke | of Toleration’) in an unidentified hand, and tearing around the remainder of a wax seal.Footnote 9 In 1922, the manuscript was consigned to Sotheby's by Edward Clarke's relative E. C. A. Sanford (1859–1923), together with two manuscripts of the Essay concerning toleration.Footnote 10 Maggs Bros. purchased the manuscript for £4 10s and subsequently advertised it in three catalogues between 1925 and 1928 for £52 10s.Footnote 11 Sometime after its third advertisement, the manuscript was sold to Paul Hyde Bonner (1893–1968), the American novelist,Footnote 12 whose own collection was auctioned in 1934 by Anderson Galleries in Manhattan.Footnote 13 From there, the manuscript entered the possession of a ‘Mr Henry MacDonald of New York’, who presented it at a time we cannot determine to the Greenfield Library, where it has remained since.

Edward Clarke had acted as the custodian of several of Locke's manuscripts between 1683 and 1689, when Locke was an exile in the Netherlands. Yet the precise manner in which Clarke acquired the Reasons (as we will call it) remains a mystery. Clarke's age and situation in 1667 decisively rules him out as the intended reader of the Reasons; however, he would later collaborate with Locke in politics,Footnote 14 and he may have taken an interest in Locke's unpublished writings on the toleration of Catholics, possibly after reconciling himself to James II (1687) or in some attempt to justify William III's alliance with Catholic Austria (1689).Footnote 15 A plausible explanation is that the Reasons was one of the ‘many papers’ which Locke sent to Clarke in August 1683, giving him the power to burn whatever he ‘disliked’; Clarke must have retained the cache of papers after Locke's return to England in February 1689.Footnote 16

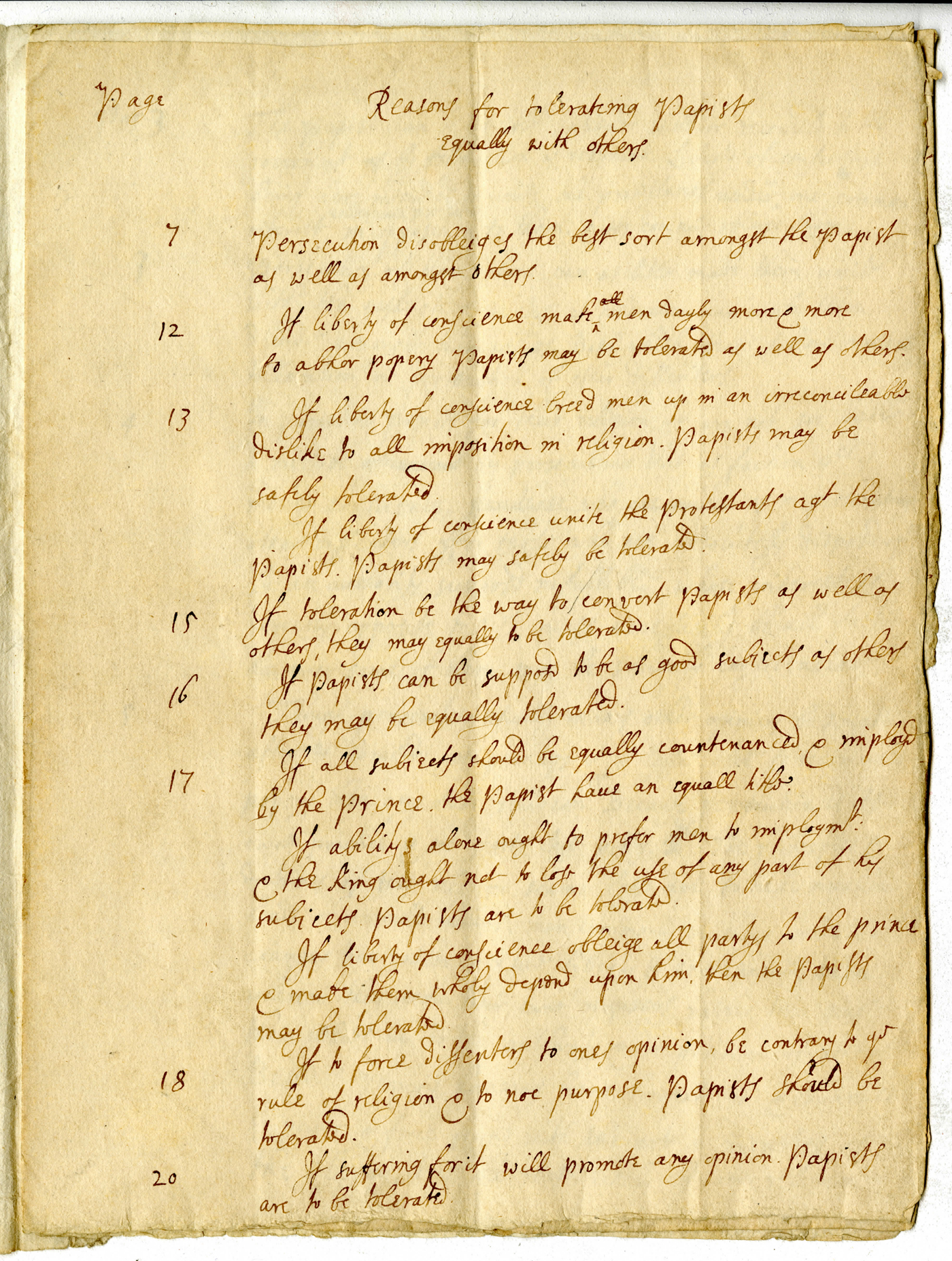

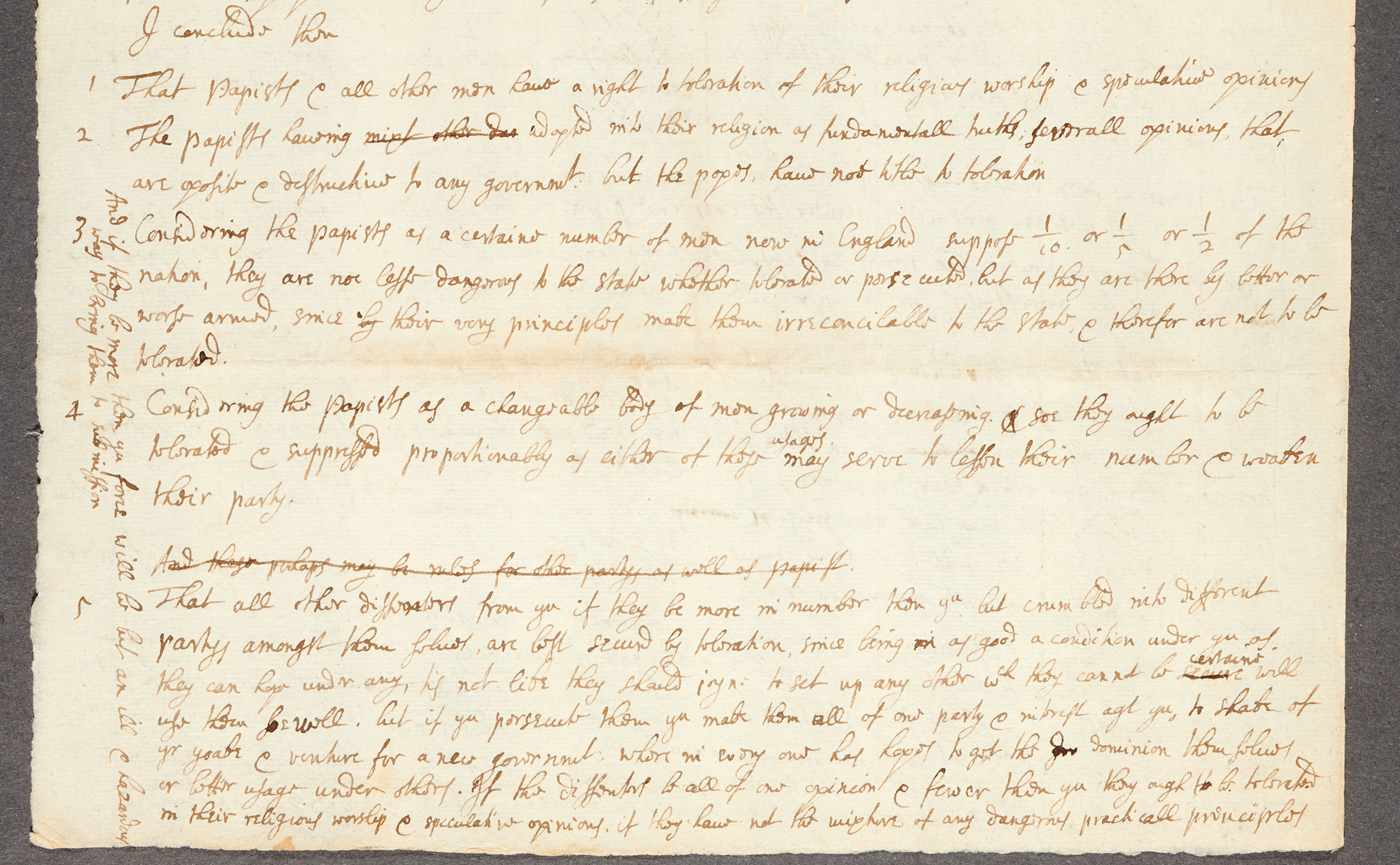

The Reasons comprises two sets of notes. At the start of each set is the marginal heading ‘Page’ / ‘Pag.’, followed by two series of numbers (‘7, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20; 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13’), each presenting Locke's response to another, unidentified work (see Figure 1). A comparison of these passages with printed books on toleration from 1667–8 reveals their source to be the first edition of Wolseley's Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest.Footnote 17 Locke has copied out the page number from Wolseley's work and variously enlarged upon, recast or responded to its arguments, in what amounts to the only surviving evidence of Locke's interest in Wolseley's publications.

Fig. 1. Greenfield Library, St John's College, Annapolis, BR1610.L8232, fo. 1r

Wolseley was a former MP (1653–60) and Cromwellian turned Royalist conspirator who had published nothing prior to 1667, and had apparently retired from public life in 1662.Footnote 18 He had served with Ashley in Barebone's Parliament and Cromwell's council of state, and he has been described as Ashley's ‘intellectual protégé’; however, the evidence of their connection after 1660 is limited.Footnote 19 In 1671–2, Ashley would dine on numerous occasions with one of Wolseley's close friends, Arthur Annesley (1614–86), the earl of Anglesey, but it is not known whether these meetings involved Wolseley.Footnote 20 Similarly, there is no evidence that Locke and Wolseley ever met. Wolseley does not feature in Locke's correspondence or manuscripts, and he is nowhere described by Locke's friends as a mutual acquaintance. Indeed, it is possible that Locke might not have identified Wolseley as the author of the Liberty of conscience…asserted & vindicated or Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest at all, since their ascription to Wolseley was not made, in print, until 1738,Footnote 21 and the absence of his name from the title pages of both works confounded several seventeenth-century readers. A contemporary manuscript criticism of Liberty of conscience…asserted & vindicated, for example, despaired of identifying the author (‘whoever he is’) in its very first line,Footnote 22 and a search of every extant copy of both Liberty of conscience pamphlets reveals a consistent perplexity. In the ninety-six copies of these works which we have located, eleven bear seventeenth-century attributions to Wolseley,Footnote 23 but five variously ascribe the works to William Penn (1644–1718),Footnote 24 John Owen (1616–83),Footnote 25 and a ‘Mr Goddard’.Footnote 26 The remainder either bear authorial ascriptions to Wolseley dating from the eighteenth century onwards,Footnote 27 or bear no ascription whatsoever.

A reader's identification of the publisher of both pamphlets might have assisted in unmasking Wolseley as their author, but the association would only have been discernible from 1675, six years after Nathaniel Ponder (1640–99) published Wolseley's The unreasonablenesse of atheism.Footnote 28 Ponder had issued the Liberty of conscience pamphlets anonymously (his name is absent from the title page and the text), but he would later announce his role as their publisher in a catalogue subjoined to an edition of William Okeley's A small monument of great mercy (1675),Footnote 29 and a reprint of John Owen's Of the mortification of sin in believers (c. 1678).Footnote 30 Ponder subsequently stocked numerous copies of both Liberty of conscience pamphlets,Footnote 31 and he appears not to have taken many precautions in their sale or conservation, possibly because the works had not attracted adverse attention in 1667–8. Soon after their appearance, the licensor Roger L'Estrange (1616–1704) had conceded that they were ‘rather to be answered than punished, except as an unlicensed pamphlet’.Footnote 32 The printer of the pamphlets, whom we can identify as John Darby (d. 1704),Footnote 33 did little to conceal his handiwork, in apparent sympathy with Ponder's indifference or in expectation of L'Estrange's response: seven ornaments used in the Liberty of conscience pamphlets recur in numerous publications from the period bearing Darby's name.Footnote 34 Locke, however, appears never to have met Darby or Ponder, and his manuscripts, publications, and correspondence do not mention them in any form.Footnote 35 It is not inconceivable that Locke suspected Wolseley's connection to the pair, or that he might have viewed the Liberty of conscience pamphlets as the product of a conjunction of printers and writers surrounding the earl of Anglesey, Ponder's close associate,Footnote 36 or John Owen, the dean of Christ Church, Oxford (1651–60), during Locke's initial residence in the college (1652–67). But the case for Locke's familiarity with such a connection would be entirely circumstantial.Footnote 37

In contrast, no difficulty surrounds our knowledge of the arguments which Locke would have encountered in Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest. In that tract, Wolseley presented a defence of toleration which, in the words of Gary S. De Krey, ‘emphasized that relief for dissenters was in the political interest of the king and the kingdom, in the religious interest of domestic and international Protestantism, and in the economic interest of the country’;Footnote 38 he exalted a ‘ballance’ between ‘divided Interests and Parties in Religion’ as a solvent of religious factionalism, and he pressed his case far enough to contemplate disestablishment. The argument was partly epistemic: coercing the conscience was a form of ‘spiritual rape’, which wrongly presupposed our ability to choose or discard religious beliefs; a state religion was ‘not alwayes infallibly true’, and its restraint on consciences could inhibit a collective, national striving towards an enlarged knowledge of religious ‘Truth’.Footnote 39 But the argument was also practical, and studded with rejoinders to the persecuting tendencies of any established religion: persecution breeds resentment and factious violence, it discourages talented office-holders ‘only because they cannot comply with some Ceremonies’, and it hinders the security of Protestantism against ‘a relapse to Popery’.Footnote 40 This final point underlay much of Wolseley's reasoning, and notionally prevented Catholics from appropriating his arguments for their cause.

In the Reasons, Locke would use the arguments presented in Wolseley's Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest as a basis to consider precisely this question, in a manner which far exceeded Wolseley's emphasis. In the first set of notes, Locke excerpts phrases from the first twenty pages of Wolseley's twenty-two-page work, and builds a case for the toleration of Catholics. In the second set, Locke returns to the work's first page and builds a case against the toleration of Catholics. In both, Locke examines three principal subjects: how Catholicism could be defended on the basis of Wolseley's positions; whether the indulgence of nonconformity would inadvertently strengthen Catholicism; and why Catholics should not be tolerated, but actively persecuted. The connection between each of these subjects and Wolseley's stimulus was close, but not imitative. Unlike Locke in the Reasons, Wolseley was adamant that the indulgence of nonconformity would in no way potentially extend to the toleration of Catholics, since a ‘Liberty for the Gospel’ could only guide believers to the intolerant detestation of papist principles. Locke's response to this claim in the first part of the Reasons typified his interpretative mode, using Wolseley's argument as the bridge to an unexpected conclusion. ‘If liberty of conscience make…men dayly more & more to abhor popery’, Locke observes, ‘Papists may be tolerated as well as others.’ This was the tendency of other notes in the first part of the Reasons, and it revealed an understandable hesitation to embrace an unqualified indulgence for Catholics, tempered by a striking impartiality. Locke's other remarks, for example, were unusually generous to Catholics: ‘If abilitys alone ought to prefer men to imployment & the King ought not to lose the use of any part of his subjects’, Locke writes, ‘Papists are to be tolerated.’ ‘If Papists can be supposd to be as good subjects as others’, Locke concedes again, ‘they may be equally tolerated.’ The tone is emollient, and nowhere replicated in Locke's works.Footnote 41

In the second part of the Reasons, however, Locke was clear that Catholics were intolerable, so long as their allegiance was in question:

I doubt whether upon Protestant principles we can justifie punishing of Papists for their speculative opinions as Purgatory transubstantiation &c if they stopd there. But possibly noe reason nor religion obleiges us to tolerate those whose practicall principles necessarily lead them to the eager persecution of all opinions, & the utter destruction of all societys but their owne. soe that it is not the difference of their opinion in religion, or of their ceremonys in worship; but their dangerous & factious tenents in reference to the state.

Exactly when Locke first consulted a copy of the Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest is difficult to establish. The dated endorsement of the Reasons (‘Toleration. 67’) suggests that Locke had encountered Wolseley's arguments prior to 25 March 1667[/8],Footnote 42 but his consultation of the work might have occurred as early as the autumn of 1667.Footnote 43 As noted above, J. R. and Philip Milton identified a close parallel between Wolseley's arguments and those advanced by Locke, but they could not establish whether the resemblance was anything more than an accident. The Reasons demonstrates Locke's interest in Wolseley's work irrefragably – and it provides a crucial piece of new evidence for the compositional history of Locke's Essay concerning toleration.

II

The Essay presented by the Miltons was a collation of four manuscripts, each of which they assigned a siglum: H (Huntington Library, San Marino, HM 584), A (‘Adversaria 1661’, Bodleian Library, MS Film 77, pp. 106–25), O (Bodleian Library, MS Locke c. 28, fos. 21r–32v), and P (The National Archives, Kew, PRO 30/24/47/1). The relationship of the manuscripts is complex, but the following facts about their composition are significant for our purposes. H is in Locke's hand and it is the urtext of A, O, and P, which differ from it in several respects. H is a set of twenty-one folded half-sheets gathered into five quires signed A to E: quires B–C present Locke's views of the fundamental principles of toleration, and they are heavily revised; quire A presents a fair copy of part of the text of quire B; and quires D–E discuss what the magistrate ought to do in practice; significantly, the text on quire D begins afresh at the top of a page, which may indicate a discontinuity in composition with quire C. H ends with the phrase ‘Sic cogitavit Atticus 1667’, and it is endorsed ‘Toleration. 67’; when sold in 1922, it was accompanied by a single half-sheet (F) containing a 1,600-word ‘first draft’ of some of its passages.Footnote 44 The Miltons assert that the composition of the Essay’s earliest versions (F and H) was most probably completed in late 1667 or early 1668.Footnote 45

There are a number of circumstances which directly connect the Reasons with F and H. First, the Reasons, F, and H were all owned by Edward Clarke's relative and consigned for sale as a batch in 1922, as we have noted.Footnote 46 Second, the watermarks of the Reasons closely match those of F, and those of quire D of H, indicating that they might have derived from the same source of paper.Footnote 47 Third, two passages which appear in the Reasons also appear, in a somewhat modified form, in quire D of H. In the first passage, Locke anticipates the claim that Catholicism in England would benefit from persecution, since people could inquire into condemned principles out of sympathy or mental instability (bold here highlights the differences between the texts):

In the second passage, Locke anticipates the objection that the persecution of Catholics may violate a defence of toleration in matters of speculative belief:

While there are numerous differences between the passages as presented in the Reasons and H, one change strongly indicates which manuscript preceded which. In the Reasons, Locke writes that ‘men commonly in their voluntary changes doe rather persue liberty & enthusiasme’. In H, Locke first wrote the same phrase, but then deleted the word ‘rather’. It is improbable that Locke wrote out the phrase in H and deleted the word ‘rather’, but when copying the phrase into the Reasons, reinstated the deletion. It is much more plausible to suppose that Locke first wrote out the phrase in the Reasons, but when copying it into H, decided to delete the word ‘rather’; the texts presented in A, O, and P all appear to derive from the wording of this passage as it is presented in H. If Locke wrote the Reasons after writing H, and was copying this passage from H to the Reasons, why did he alter it, when he made no such alterations when copying it into A, O, and P? These considerations make it virtually certain that the Reasons was a source for the passage which reappears in quire D of H.

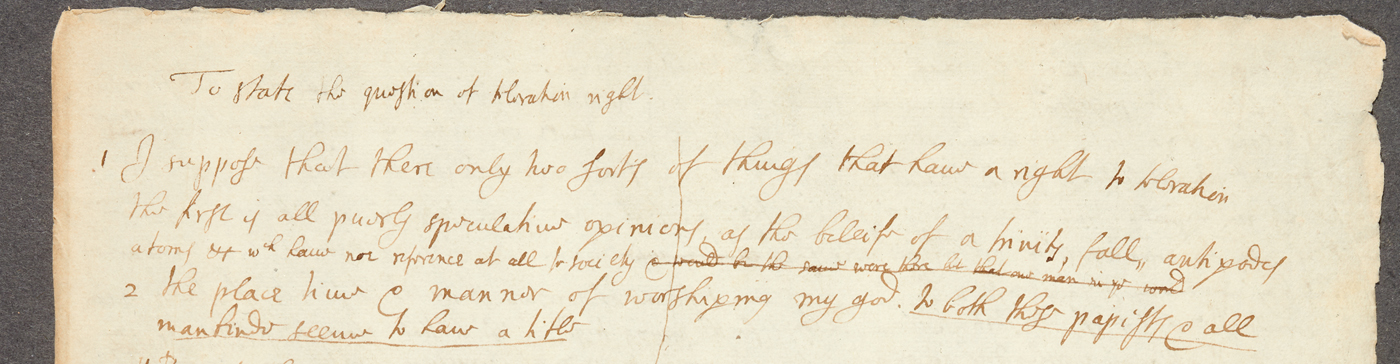

A consideration of the content and composition of F – the ‘first draft’ of the Essay – also suggests that the Reasons preceded not only those parts of quire D in which its phrases are recycled, but any earlier draft of the Essay as a whole. Locke began F with the general intention ‘To state the question of toleration right’. He subsequently listed two ‘sorts of things’ that have a ‘right to toleration’:

the first is all puerly speculative opinions, as the beleife of a trinity, fall, antipodes atoms &c which have noe reference at all to society 2 the place time & manner of worshiping my god. To both these papists & all mankinde seeme to have a title〈.〉Footnote 51

Locke underlined the last phrase focusing on Catholics (‘To both these papists & all mankinde seeme to have a title’), possibly in order to indicate a deletion (see Figure 2). This phrase, however, suggests that Locke began F with the toleration of Catholics at the forefront of his mind. The remainder of F sets the tone for much of Locke's later writing on toleration (‘I ought to have liberty in my religious worship, because it is a thing betweene god and me, & is of an eternall concernment wheras the magistrate is umpire between man & man’),Footnote 52 but the conclusion returns again to the question of whether Catholics should be tolerated (see Figure 3). Indeed, when first written, the conclusion of F terminated with a list of four policy proposals focused particularly on the toleration of Catholics; Locke wrote that while ‘Papists & all other men have a right to toleration of their religious worship & speculative opinions’, having ‘adopted into their religion as fundamentall truths, severall opinions, that are oposite & destructive to any government but the popes, [they] have noe title to toleration’. The opening and closing of F, as it was originally conceived, were thus focused on the toleration of Catholics, in a manner which suggests that this was the original subject of the manuscript. In what was evidently a later addition, Locke noted that his conclusions might have wider applications than the toleration of Catholics alone, and conceded that ‘these perhaps may be rules for other partys as well as papists’. Later still, Locke deleted this phrase and added a fifth policy proposal concerning ‘all other dissenters’, lengthening the paper by roughly 160 words, and broadening its scope beyond Catholics tout court.

Fig. 2. Huntington Library, HM 584 (F), fo. 1r, detail

Fig. 3. Huntington Library, HM 584 (F), fo. 1v, detail

This raises the possibility that the Reasons antedated not just quire D of H, but F itself, the first draft of the Essay concerning toleration. It is possible that after Locke wrote F he wished to analyse the question of Catholic toleration in more detail, and wrote the Reasons as a product of this desideratum. Yet this seems less probable than a scenario in which Locke wrote the Reasons first and F subsequently: why would Locke seek Reasons for tolerateing Papists equally with others, and entertain the possibility that Catholics could be tolerated, when he had already concluded at the end of F that ‘Papists…have noe title to toleration’?Footnote 53 Instead, F, prior to revision, reads like a more systematic treatment of the questions first addressed in the Reasons. In such a scenario, having constructed some initial arguments for and against the toleration of Catholics in the Reasons, Locke then chose to present a more elaborate treatment of this topic in the unrevised form of F; further consideration led Locke to broaden the scope of F to encompass nonconformists, pressing him to commence the Essay proper with a broadened focus on toleration in general. Such a situation, in which Locke's interest in a specific topic transformed into a more expansive work, has a direct parallel elsewhere in his writings; the Essay concerning human understanding began in c. 1671 as a consideration of ‘morality and reveal'd religion’, but quickly expanded from the ‘one sheet of Paper’ Locke initially anticipated, into a sprawling project which continued for the remainder of his life.Footnote 54

If we suppose a similar development in this instance, the Reasons would explain why the conclusions in the initial version of F were so focused on ‘Papists’; the question of Catholic toleration was that which Locke originally set out to answer. Locke then revised F to compass Protestant dissenters within the scope of his arguments, adopted a broader perspective, and comprehensively formulated his mature views on toleration for the first time. In such a scenario, the Reasons would be the immediate antecedent of the Essay, presenting aspects of Locke's later thinking on toleration in an embryonic form.

In the same manner, the Reasons would also raise questions about the order of composition of the Essay. The similarity in watermarks between the Reasons, F, and quire D of H could plausibly bracket their composition into a distinctive phase. In such a phase, Locke procured a sheaf of paper and wrote the Reasons; using the same paper, he consecutively completed F and quire D. In a subsequent phase, Locke changed his paper stock and completed quires E and A–C.Footnote 55 This sequence (quires D–E, B–C, A) is not an essential part of our argument, but it would incidentally align with the disparate focus of the quires’ concerns: A–C include text which is concerned with the fundamental principles of toleration; D–E include text which is concerned with what a magistrate ought to do in practice. It would be reasonable to assume that the composition of H occurred in these phases, mirroring the disparity of its quires’ content and paper. As noted above, the text at the beginning of quire D is discontinuous with that at the end of quire C. It would be perfectly possible for Locke to have completed his revisions of F, dealing with the principles of toleration in general, only subsequently to consider the practicalities of the magistrate's actions in quire D, without having first completed quires A–C.

This hypothesis aside, the Reasons highlights two important – but previously indemonstrable – features of Locke's Essay concerning toleration: a focus on Catholicism and a dependence upon contemporary debate. In reference to the former, the Reasons reveals how the spectre of Catholicism animated Locke's earliest theory of toleration, and helped shape its first expression. In this connection, it is important to re-emphasize that Locke's stance on the indulgence of Catholics, prior to 1667–8, had been intransigently hostile. His response to Stubbe of 1659 had refused to allow that a ‘liberty’ to Catholics could ‘consist with the security of the Nation’: ‘since I cannot see how they can at the same time obey two different authoritys carrying on contrary intrest espetially where that which is destructive to ours ith [sic] backd with an opinion of infalibility and holinesse supposd by them to be immediatly derivd from god’.Footnote 56 Within eight years, however, Locke was prepared to admit that Catholics could benefit from a form of toleration which denied the possibility of coercing beliefs, to the extent that F described this principle as the basis of a ‘right to toleration’: ‘Papists & all other men have a right to toleration of their religious worship & speculative opinions.’Footnote 57 Yet Locke was evidently dissatisfied with this concession, and he did not include a ‘right to toleration’ of any kind for Catholics in H, A, O, or P. Instead, the Essay insisted on the magistrate being assured that ‘doctrines absolutely destructive’ to society could be ‘separated’ from Catholic religious worship before the indulgence of Catholics could be countenanced ― the position which Locke would hold throughout the Epistola de tolerantia and his Letters (1690–2) on toleration:

These [sc. Roman Catholics] therefor blending such opinions with their religion, reverencing them as fundamentall truths, & submitting to them as articles of their faith, ought not to be tolerated by the magistrate in the exercise of their religion unlesse he can be securd, that he can allow one part, without the spreading of the other, & that the propagation of these dangerous opinions may be separated from their religious worship.Footnote 58

Locke would consistently associate Catholicism with a fixed belief in the pope's temporal supremacy; the Epistola appeared to describe it as an ‘ipso facto’ component of Catholic worship.Footnote 59 Yet Locke would also suppose that this fixed belief could be renounced, and he later evinced an apparent interest in an ‘Oath of Allegiance’ for English Catholics, in which the creedal rudiments of Catholicism would be emptied of ‘dangerous opinions’.Footnote 60 The Reasons was not a prelude to this doctrine per se, but a sign that Locke was prepared to reconsider its governing presumption: the idea that Catholics could not be tolerated until they had sufficiently reformed their political theology.Footnote 61 The difficulty is whether Locke used the Reasons to endorse this position or merely to dispute its merits in utramque partem. Every indication suggests the latter – and not least Locke's explicit intolerance of Catholics who held ‘dangerous & factious tenents in reference to the state’.

In the context of the religious politics of the Ashley circle, the implications of Locke's stance in the Reasons are significant for their ambiguity. The option of according or denying Catholics a ‘right to toleration’ might have proceeded from Ashley's inclinations, but it is difficult to know what these were between the aborted Declaration of Indulgence of 1662 and the Treaty of Dover of 1670.Footnote 62 Ashley's relationship with a Catholic bloc at court, represented principally by Queen Henrietta Maria, Queen Catherine, Henry Bennet (1618–85), the earl of Arlington, and Thomas Clifford (1630–73),Footnote 63 is insusceptible of reconstruction; any sense that the Essay was written at Ashley's request is questionable in itself, but it is particularly difficult to imagine that he might have instructed Locke to accept the bloc's designs for Catholic relief, assuming that these were known or meaningfully formulated before 1670. It is entirely possible that Ashley and Locke had expected that Charles II would issue an indulgence for Catholics in 1668, packaged with a salve to nonconforming consciences: Locke foresaw that a justification would be required to defend the policy and he wrote the Reasons in politique obedience to this prediction, or in anticipation of Ashley's purposes.

Yet an alternative possibility runs in a different direction. From Locke's perspective, Catholicism served as the crux of a consistent theory of toleration, in which the difficulty was double-sided: how could a theorist argue for Catholic persecution without vitiating a case for the indulgence of nonconformity? A resurgence of Catholicism had evidently suggested itself as the effect of a forthcoming indulgence; a note dating from early 1667 in one of Locke's memorandum books reveals that he feared Catholic intentions for England: ‘Papist | for carrying on the designe of the Papists in Englan〈d〉 | V〈ide〉 | Campanella | Adam Contzen | Hieron’.Footnote 64 Locke also cited these individuals in a booklist from around this time under the heading ‘Politici’, noting: ‘In these three last authors you have the ways & methods describd of the Papists carrying on their designe in England.’Footnote 65 The question of Catholic loyalty was clearly a matter of some on-going interest before Locke's move to London to take up his position in Ashley's household, and it would be reasonable to assume that this fear persisted during the composition of the Reasons.

Wolseley's Liberty of conscience, the magistrates interest opened a new front in this debate, in that it elaborated a pragmatic case for the indulgence of nonconformity, dependent on civil ‘interest’, which required safeguards against Catholic misuse. This could explain the negative conclusion which the Reasons appears to endorse. Locke might have nominally sought ‘reasons’ for tolerating Catholics, but he was insistent – in the first and later drafts of the Essay concerning toleration, and every later iteration of his theory – that Catholics were intolerable, insofar as their allegiance remained in doubt. What distinguished the Reasons, on this reading, was the charity of its assumptions: Locke was willing to contemplate the toleration of Catholics in a fashion which others would never countenance, and he did so with startling impartiality. This interpretation does not rely on any specific claim about the precedence of the Reasons or the Essay; it is possible that Locke wrote the Reasons alongside or after the Essay, in order to clarify his positions or satisfy his curiosity. But this alternative would issue in the same observation: in 1667–8, Catholicism and allegiance preoccupied Locke in a manner which we have so far failed to appreciate.

The Reasons has a second, but equally novel, significance. Nothing in Locke's correspondence or manuscripts had previously shed light on the relationship of the Essay with Locke's interest in contemporary debates.Footnote 66 Yet it is clear from the Reasons that Locke held some measure of interest in another living theorist of toleration.Footnote 67 If it is true that the arguments which Locke employed in the Essay ‘were his own’, as the Miltons have contended, the extent to which these arguments were produced in the company of pamphleteers – instead of abstracted contemplation – must now be recognized, and further explored.

III

Editorial conventions. Our transcription retains the manuscript's original spelling, capitalization, and punctuation, with the following exceptions. Manuscript forms for words such as ‘ye’, ‘yu’, ‘wch’ have been replaced by the usual printed forms, as have suffixes such as ‘-mt’ [ment]. Contractions and abbreviations such as ‘K’ [King], and ‘nāāl’ [natural] have been silently expanded. Italics are used for scribal interlineations, strikethroughs for scribal deletions, and double strikethroughs for scribal cancellation by superimposition. Angle brackets 〈 〉 are used for editorial insertion or substitution in a text, and a raised dot · for an editorial stop.

Transcription. Greenfield Library, St John's College, Annapolis, BR1610.L8232

|fo. 1r|

|fo. 1v| [blank]

|fo. 2r|